Abstract

We examine how rewards and penalties under tournament incentives impact price behaviour in experimental asset markets. Adding a penalty to a reward-only contract, or a reward to a penalty-only contract, changes the traders’ behaviour. The experimental markets with adjusted contracts experience less trading, but longer-lived and larger bubbles. This observed effect of penalties is consistent with herd-driven behaviour under relative performance evaluation, while the effect of rewards reflects the influence of the convexity of bonuses. However, these effects dissipate with trader experience. Our findings contribute to the debate attributing market instability to incentive structures in the finance industry.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

To further highlight the difference, Kleinlercher et al. (2014) point out that it is possible under their bonus compensation contract for all traders to receive a bonus, since with a favourable dividend outcome, all traders could exceed the benchmark-level of cash. In the absence of collusion, this is not possible in tournament schemes where bonuses are paid for above-average performance, since someone must perform below average.

A screenshot of the trading interface can be found in Online Resource 1.

These dividend structures mimic that of Ackert et al. (2006), who also use a standard/lottery-asset dichotomy, though theirs has a much more pronounced difference in potential payoffs between the two types. This difference is intentional, as we wanted participants to view Asset Y as a viable “investment” rather than a purely speculative bet.

The expected value of the total future dividend stream was common knowledge, and was communicated to all participants in the form of an “average holding value” table in the written instructions.

To prevent the other features of the graph from being obscured, the step function corresponding to the maximum cumulative dividends for asset Y (black dashed line) is only partially displayed.

In periods where there was no trade in an asset, the median transaction price was replaced by the median buy offer for that asset in the period. This was done to avoid misleading fluctuations in the Account Total, and participants were made aware of this before the market began.

To ensure consistency with the procedures used in the existing literature, the written protocol was adapted from Dufwenberg et al. (2005), Noussair et al. (2001), Noussair and Powell (2010), Lugovskyy et al. (2009), Childs and Mestelman (2006), and Cheung and Coleman (2014). Participants were also given time to read the instructions on their own, and to ask any clarifying questions privately (which were also answered privately). The written protocol is reproduced in Online Resource 1, which can be obtained from the authors.

The survey can be found in Online Resource 2, which is available from authors.

This is a modified version of the end-of-experiment questionnaire used by Ackert and Church (2001).

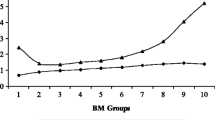

The evolution of median transaction prices in each individual market of the Linear, Carrot, CarrStick, and Stick treatment can be found in Online Resource 3, which can be obtained from the authors.

Unlike Fisher and Kelly (2000), we report the median of the Prediction Errors across all sessions/markets rather than the average, due to the lower sensitivity of the median to outliers in small samples.

The behaviour of Prediction Error in the individual markets of the Linear, Carrot, CarrStick, and Stick treatments can be seen in Online Resource 3, which can be obtained from the authors.

The bubble measure values observed in the individual markets of each treatment are tabled in Online Resource 4, which can be obtained from the authors.

The CRT/DOSPERT data was collected after the market, hence it is possible that traders’ market experiences influenced their responses. However, random assignment of participants to treatments should ensure that the treatment groups are on average ‘equivalent’ at the outset of the experiment. Nonetheless, we tested for differences as an additional safety measure. No significant differences between any of the four treatments were detected on DOSPERT or CRT scores. However, as noted earlier, the results regarding the effect of rewards should be interpreted with caution due to the fact that the treatment group for the Stick treatment was not ‘equivalent’ to the CarrStick group at the outset of the experiment.

We omit the Stick results to mitigate any concerns about the difference in the sample.

The statistical significance of the median Geometric Prediction Error in each treatment is assessed using the one-sample Wilcoxon Signed-rank test, under the null that the median is equal to zero.

Available from the corresponding author on request.

Even though the median value of Geometric Deviation for asset X in the Linear treatment is smaller in Round 2, the signed-rank test actually implies a marginally significant increase in the measure because the Round 2 value is larger than the corresponding Round 1 value in 6 out of 7 markets.

Indeed, the standard random effects model is biased and inconsistent if the between and within effects are not the same. The correlated random-effects model (Mundlak 1978), which is closely related to the hybrid model.

References

Acker, D., & Duck, N. W. (2006). A tournament model of fund management. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, 33(9–10), 1460–1483.

Ackert, L. F., Charupat, N., Church, B. K., & Deaves, R. (2006). Margin, short selling, and lotteries in experimental asset markets. Southern Economic Journal, 73(2), 419–436.

Ackert, L. F., & Church, B. K. (2001). The effects of subject pool and design experience on rationality in experimental asset markets. Journal of Psychology and Financial Markets, 2(1), 6–28.

Allen, F., & Gorton, G. (1993). Churning bubbles. Review of Economic Studies, 60(4), 813–836.

Allen, F., & Gale, D. (2000). Financial contagion. The Journal of Political Economy, 108(1), 1–33.

Bagnoli, M., & Watts, S. G. (2000). Chasing hot funds: The effects of relative performance on portfolio choice. Financial Management, 29(3), 31–50.

Bebchuk, L. A., & Spamann, H. (2009). Regulating bankers’ pay. Georgetown Law Journal, 98, 247.

Blais, A.-R., & Weber, E. U. (2006). A Domain-Specific Risk-Taking (DOSPERT) scale for adult populations. Judgment and Decision Making, 1(1), 33.

Blinder, A. S. (2009). Crazy compensation and the crisis. The Wall Street Journal, http://www.wsj.com/articles/SB124346974150760597. Accessed 16 January 2015.

Brown, K. C., Harlow, W. V., & Starks, L. T. (1996). Of tournaments and temptations: An analysis of managerial incentives in the mutual fund industry. The Journal of Finance, 51(1), 85–110.

Busse, J. A. (2001). Another look at mutual fund tournaments. The Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 36(1), 53–73.

Cabral, L. M. B. (2003). R&D competition when firms choose variance. Journal of Economics & Management Strategy, 12(1), 139–150.

Caginalp, G., Porter, D., & Smith, V. L. (1998). Initial cash/asset ratio and asset prices: An experimental study. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 95(2), 756–761.

Caginalp, G., Porter, D., & Smith, V. L. (2000). Overreactions, momentum, liquidity, and price bubbles in laboratory and field asset markets. Journal of Psychology & Financial Markets, 1(1), 24–48.

Caginalp, G., Porter, D., & Smith, V. L. (2001). Financial bubbles: Excess cash, momentum, and incomplete information. The Journal of Psychology and Financial Markets, 2(2), 80–99.

Chan, K. S., Lei, V., & Vesely, F. (2013). Differentiated assets: An experimental study on bubbles. Economic Inquiry, 51(3), 1731–1749.

Chen, H.-L., & Pennacchi, G. G. (2009). Does prior performance affect a mutual fund’s choice of risk? Theory and further empirical evidence. The Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 44(4), 745–775.

Cheung, S. L., & Coleman, A. (2014). Relative performance incentives and price bubbles in experimental asset markets. Southern Economic Journal, 81(2), 345–363.

Chevalier, J., & Ellison, G. (1997). Risk taking by mutual funds as a response to incentives. Journal of Political Economy, 105(6), 1167–1200.

Childs, J., & Mestelman, S. (2006). Rate-of-return parity in experimental asset markets. Review of International Economics, 14(3), 331–347.

Dass, N., Massa, M., & Patgiri, R. (2008). Mutual funds and bubbles: The surprising role of contractual incentives. Review of Financial Studies, 21(1), 51–99.

Dufwenberg, M., Lindqvist, T., & Moore, E. (2005). Bubbles and experience: An experiment. The American Economic Review, 95(5), 1731–1737.

Elton, E. J., Gruber, M. J., & Blake, C. R. (2003). Incentive fees and mutual funds. The Journal of Finance, 58(2), 779–804.

Elton, E. J., Gruber, M. J., Blake, C. R., Krasny, Y., & Ozelge, S. O. (2010). The effect of holdings data frequency on conclusions about mutual fund behavior. Journal of Banking & Finance, 34(5), 912–922.

Fischbacher, U. (2007). z-Tree: Zurich toolbox for ready-made economic experiments. Experimental Economics, 10(2), 171–178.

Fisher, E. O. N., & Kelly, F. S. (2000). Experimental foreign exchange markets. Pacific Economic Review, 5(3), 365–387.

Frederick, S. (2005). Cognitive reflection and decision making. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 19(4), 25–42.

Gaba, A., & Kalra, A. (1999). Risk behavior in response to quotas and contests. Marketing Science, 18(3), 417–434.

Gaba, A., Tsetlin, I., & Winkler, R. L. (2004). Modifying variability and correlations in winner-take-all contests. Operations Research, 52(3), 384–395.

Gilpatric, S. M. (2009). Risk taking in contests and the role of carrots and sticks. Economic Inquiry, 47(2), 266–277.

Goriaev, A., Nijman, T. E., & Werker, B. J. M. (2005). Yet another look at mutual fund tournaments. Journal of Empirical Finance, 12(1), 127–137.

Greiner, B. (2015). Subject pool recruitment procedures: Organizing experiments with ORSEE. Journal of the Economic Science Association, 1(1), 114–125.

Haruvy, E., & Noussair, C. N. (2006). The effect of short selling on bubbles and crashes in experimental spot asset markets. The Journal of Finance, 61(3), 1119–1157.

Hu, P., Kale, J. R., Pagani, M., & Subramanian, A. (2011). Fund flows, performance, managerial career concerns, and risk taking. Management Science, 57(4), 628–646.

Hvide, Hans K. (2002). Tournament rewards and risk taking. Journal of Labor Economics, 20(4), 877–898.

Isaac, R. M., & James, D. (2003). Boundaries of the tournament pricing effect in asset markets: Evidence from experimental markets. Southern Economic Journal, 69(4), 936–951.

James, D., & Isaac, R. M. (2000). Asset markets: How they are affected by tournament incentives for individuals. The American Economic Review, 90(4), 995–1004.

Kempf, A., & Ruenzi, S. (2008). Tournaments in mutual-fund families. Review of Financial Studies, 21(2), 1013–1036.

Kempf, A., Ruenzi, S., & Thiele, T. (2009). Employment risk, compensation incentives, and managerial risk taking: Evidence from the mutual fund industry. Journal of Financial Economics, 92(1), 92–108.

King, R., Smith, V. L., Williams, A. W., & Boening, M. V. (1993). The robustness of bubbles and crashes in experimental stock markets. In R. Day & P. Chen (Eds.), Non linear dynamics and evolutionary economics (pp. 183–2999). Oxford: Oxford Press.

Kleinlercher, D., Huber, J., & Kirchler, M. (2014). The impact of different incentive schemes on asset prices. European Economic Review, 68, 137–150.

Koski, J. L., & Pontiff, J. (1999). How are derivatives used? Evidence from the mutual fund industry. The Journal of Finance, 54(2), 791–816.

Lugovskyy, V., Puzzello, D., & Tucker, S. J. (2010). An experimental investigation of overdissipation in the all pay auction. European Economic Review, 54(8), 974–997.

Mundlak, Y. (1978). On the pooling of time series and cross section data. Econometrica, 46(1), 69–85.

Nieken, P., & Sliwka, D. (2010). Risk-taking tournaments—Theory and experimental evidence. Journal of Economic Psychology, 31(3), 254–268.

Noussair, C. N., & Powell, O. (2010). Peaks and valleys: Price discovery in experimental asset markets with non-monotonic fundamentals. Journal of Economic Studies, 37(2), 152–180.

Noussair, C., Robin, S., & Ruffieux, B. (2001). Price bubbles in laboratory asset markets with constant fundamental values. Experimental Economics, 4(1), 87–105.

Palan, Stefan. (2013). A review of bubbles and crashes in experimental asset markets. Journal of Economic Surveys, 27, 570–588.

Porter, D. P., & Smith, V. L. (1995). Futures contracting and dividend uncertainty in experimental asset markets. Journal of Business, 68(4), 509.

Powell, O. (2016). Numeraire independence and the measurement of mispricing in experimental asset markets. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance, 9, 56–62.

Qiu, J. (2003). Termination risk, multiple managers and mutual fund tournaments. European Finance Review, 7(2), 161–190.

Rajan, R. G. (2006). Has finance made the world riskier? European Financial Management, 12(4), 499–533.

Rajan, R. G. (2008). Bankers’ pay is deeply flawed. Financial Times. http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/18895dea-be06-11dc-8bc9-0000779fd2ac.html#axzz3T9uTJuUR. Accessed 16 January 2015.

Robin, S., Straznicka, K., & Villeval, M. (2012). Bubbles and incentives: An experiment on asset markets. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2197754.

Schoenberg, E. J., & Haruvy, E. (2012). Relative performance information in asset markets: An experimental approach. Journal of Economic Psychology, 33(6), 1143–1155.

Smith, V. L., Suchanek, G. L., & Williams, A. W. (1988). Bubbles, crashes, and endogenous expectations in experimental spot asset markets. Econometrica, 56(5), 1119–1151.

Smith, V. L., van Boening, M., & Wellford, C. P. (2000). Dividend timing and behavior in laboratory asset markets. Economic Theory, 16(3), 567–583.

Taylor, J. (2003). Risk-taking behavior in mutual fund tournaments. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 50(3), 373–383.

Tsetlin, I., Gaba, A., & Winkler, R. (2004). Strategic choice of variability in multiround contests and contests with handicaps. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 29(2), 143–158.

Wagner, W. (2013). Performance evaluation and financial market runs. Review of Finance, 17(2), 597–624.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank two anonymous referees and Charles Noursair (the editor) for suggestions. We also thank David Feldman, Thomas Henker, Jeremy Clark, Kenan Kalayci and session participants at the 2015 Experimental Finance Meeting, the 2015 European Financial Management Association meeting, and the UNSW brown bag and seminar participants at the University of Maine and the University of Tasmania for helpful comments. We gratefully acknowledge financial support provided by the Australian Research Council (ARC DECRA Grant Number: DE120101523).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Paul, D.J., Henker, J. & Owen, S. The aggregate impacts of tournament incentives in experimental asset markets. Exp Econ 22, 441–476 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10683-018-9562-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10683-018-9562-7