Abstract

In this paper we experimentally investigate the impact that competing for funds has on the risk-taking behavior of laboratory portfolio managers compensated through an option-like scheme according to which the manager receives (most of) the compensation only for returns in excess of pre-specified strike price. We find that such a competitive environment and contractual arrangement lead, both in theory and in the lab, to inefficient risk taking behavior on the part of portfolio managers. We then study various policy interventions, obtained by manipulating various aspects of the competitive environment and the contractual arrangement, e.g., the Transparency of the contracts offered, the Risk Sharing component in the contract linking portfolio managers to investors, etc. While all these interventions would induce portfolio managers, at equilibrium, to efficiently invest funds in safe assets, we find that, in the lab, Transparency is most effective in incentivising managers to do so. Finally, we document a behavioral “Other People’s Money” effect in the lab, where portfolio managers tend to invest the funds of their investors in a more risky manner than their Own Money, even when it is not in either the investors’ or the managers’ interest to do so.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In our experiments, managers face the choice between the safe and the risky investment. These investment opportunities are constructed in such a way that both risk neutral and risk averse individuals unambiguously prefer the safe investment since it has a higher expected return and a lower variance. Thus, even though we do not measure directly investors’ risk preferences or managers’ beliefs about investors’ risk preferences, one would have to assume that investors are risk loving or managers’ mistakenly believe that they are in order to interpret our experimental results differently.

We shall argue at the end of this section that this is a reasonable representation of the contractual environment which is found in hedge fund markets.

We abstract from small fixed fees, which possibly have little effect on risk taking in practice.

Risk neutrality is therefore assumed just for simplicity and because our theoretical analysis is meant to guide the experimental analysis, which has relatively small stakes. On the other hand, all our results are qualitatively unchanged allowing for some risk aversion; more specifically, as long as the manager’s objective remains convex.

See Matutes and Vives (2000) for a model of bank competition which resembles, along several dimensions, our laboratory capital market.

This result holds true more generally, when managers in capital markets compete by choosing both the share, β, of all profits made above a “high-water mark”/strike price, w, and the “high-water mark”/strike price, w itself (see Online Appendix for the formal proof).

The first hedge fund was apparently founded by A.W. Jones, a sociologist and financial journalist, in 1949. In the 1990’s, however, the industry was managing about $50 billions; see Malkiel and Saha (2005).

A norm in the market seems to be “2/20” contracts: 2 % management and 20 % performance fee.

In this sense it is preferable to repeating the Own Money (small stakes) treatment 20 times since in that treatment repetition may lead to boredom and false diversification.

The results of the test do not change if we take into account all the intended investments of manager and not just the ones who received the chip from the investor.

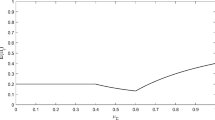

Our data suggests that there is some resistance to offering an w much above 7. In fact the highest watermark offered in the last 5 rounds was 7.9 tokens. This may be explained by a number of reasons. For example, in the Baseline treatment there is a residual 37 % of subjects who intended to invest in the safe project in the last 5 rounds. Those subjects almost never promised more than 7 tokens. Hence, a manager intending to invest in the risky project may have believed that it was not necessary to offer more than 7 since there was a good chance that he would be facing a safe investor who he believed would never offer more than 7.

With the exception being the Cap on Watermarks treatment in the last 5 periods, in which the fraction of risky investments is significantly smaller than the one documented in the Baseline treatment at 10 % (rather than 5 %) level of significance.

All the comparisons are made based on the results of the Wilcoxon Ranksum test for equality of medians using the fraction of risky investments averaged per session, which gives us 4 observations per treatment.

We note that managers who chose the safe project in the Transparency treatment offer on average strike price of 4.6 which is above theoretical threshold value of 3.25. One possible explanations for the inconsistency between offering strike price above the threshold and investing in the safe project might be the mistakes subjects make in calculations. In other words, subjects are able to internalize main trade-offs of the environment they face; however, they make small mistakes in calculations which lead them to believe that the threshold is higher than it actually is. Importantly, subjects that perform the role of managers realize that risky investments should be accompanied by the premium in returns, which is what we observe.

Such a small number of observations in Cap on Watermark treatment is due to the fact that in the last 5 periods of the game both managers proposed the same maximum possible watermark to investors, which is \(\bar{w}=3\).

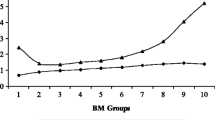

We note that there is a difference in the stake size between Risk Sharing, Own Money (small stakes) and Own Money (big stakes) treatment. Indeed, in the Risk Sharing treatment managers on average 38 % of the profits and give the rest to the investor (see Table 6). In the Own Money (small stakes) managers enjoy 100 % of earned profits as they do not face the competition for funds and receive investment chip for free in every round. Finally, in the Own Money (big stakes) treatment the stakes are much higher than in both Own Money (small stakes) and Risk Sharing treatment. Despite these differences, we believe that the point we are trying to make in this section is not driven by the difference in stake sizes. The point being that managers make riskier investments when operating with the funds received from the investor than when they invest their own funds.

Recall that the Own Money (big stakes) treatment was performed at the end of each session after another treatment. There is, however, no significant difference in the behavior of either managers or investors according to the different treatments they previously played (p>0.10). Therefore, we pool together all the data from Own Money (big stakes) treatment and report them together.

The difference in managers’ behavior in the last round resembles end-game effects which are often observed in the experiments on finitely repeated games, albeit that in our experiment managers behave significantly more risky in the very last round, while in the repeated games subjects tend to be more selfish in the very last round of the experiment (see Reuben and Suetens 2009 and the references mentioned there). Further investigation is required to establish whether this feature is common to other risky environments.

While we couch our discussion with reference to the hedge fund market, our interests are broader than that since our results hold for any market where firms compete for funds.

This suggests that the effects we found in the Baseline treatment would be even stronger in the situation, in which the risky asset has a higher expected return to compensate for the additional risk of holding this asset.

References

Amin, G. S., & Kat, H. M. (2002). Welcome to the dark side: hedge fund attrition and survivorship bias over the period 1994–2001. ISMA Centre Discussion Papers In Finance 2002-02.

Asparouhova, E., Bossaerts, P., Copic, J., & Cornell, B. (2011). Competition in portfolio management: theory and experiment. Mimeo, Caltech.

Brennan, G., Gonzales, L., Guth, W., & Levati, V. M. (2008). Attitudes toward private and collective risk in individual and strategic choice situations. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 67, 253–262.

Brown, S. J., Goetzmann, W. N., & Park, J. (2001). Careers and survival: competition and risk in the hedge fund and CTA industry. The Journal of Finance, 56(5), 1869–1886.

Carpenter, J. (2000). Does option compensation increase managerial risk appetite? The Journal of Finance, 55(5), 2311–2331.

Chakravarty, S., Harrison, G. W., Haruvy, E. E., & Rutstrom, E. E. (2011). Are you risk averse over other people’s money? Southern Economic Journal, 77(4), 901–913.

Edwards, F. R., & Caglayan, M. O. (2001). Hedge fund performance and manager skill. Mimeo, Graduate School of Business, Columbia University.

Ellison, G., & Chevalier, J. (1999). Carrer concerns of mutual fund managers. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 114(2), 389–432.

Eriksen, K. W., & Kvaloy, O. (2010). Myopic investment management. Review of Finance, 14, 521–542.

Fung, W., & Hsieh, D. A. (1999). A primer on hedge funds. Journal of Empirical Finance, 6, 309–331.

Goetzmann, W. N., Ingersoll, J. Jr., & Ross, S. A. (2003). High water marks and hedge fund management contracts. The Journal of Finance, 58(4), 1685–1717.

He, Z., & Xiong, W. (2010). Delegated asset management and investment mandates. Mimeo, University of Chicago Booth School of Business.

Inechen, A., & Silberstein, K. (2008). Aima’s roadmap to hedge funds. The Alternative Investment Management Association Limited.

Jackwerth, J. C., & Hodder, J. E. (2006). Incentive contracts and hedge fund management. MPRA Paper No. 11632.

Keasey, K., & Moon, P. (1996). Gambling with the house money in capital expenditure decisions: an experimental study. Economic Letters, 50(1), 105–110.

Levitt, S. D., & Syverson, C. (2008). Market distortions when agents are better informed: the value of information in real estate transactions. Review of Economics and Statistics, 90(4), 599–611.

Liang, B. (2000). Hedge funds: the living and the dead. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 35(3), 309–326.

Malkiel, B. G., & Saha, A. (2005). Hedge funds: risk and return. Financial Analysts Journal, 61(6), 80–88.

Matutes, C., & Vives, X. (2000). Imperfect competition, risk taking, and regulation in banking. European Economic Review, 44, 1–34.

Merlo, A., & Schotter, A. (1999). A surprise-quiz view of learning in economic experiments. Games and Economic Behavior, 28(1), 25–54.

Ou-Yang, H. (2003). Optimal contracts in a continuous time delegated portfolio management problem. The Review of Financial Studies, 16(1), 173–208.

Palomino, F., & Prat, A. (2003). Risk taking and optimal contracts for money managers. The Rand Journal of Economics, 34(1), 113–137.

Panageas, S., & Westerfield, M. M. (2009). High-water marks: high risk appetites? Convex compensation, long horizons, and portfolio choice. The Journal of Finance, 64(1), 1–36.

Reuben, E., & Suetens, S. (2009). Revisiting strategic versus non-strategic cooperation. CentER discussion paper 2009-22.

Thaler, R. H. (1985). Mental accounting and consumer choice. Marketing Science, 4(3), 199–214.

Thaler, R. H. (1999). Mental accounting matters. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 12, 183–206.

Thaler, R. H., & Johnson, E. J. (1990). Gambling with the house money and trying to break even: the effects of prior outcomes on risky choices. Management Science, 36(6), 643–660.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic Supplementary Material

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Agranov, M., Bisin, A. & Schotter, A. An experimental study of the impact of competition for Other People’s Money: the portfolio manager market. Exp Econ 17, 564–585 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10683-013-9384-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10683-013-9384-6