Abstract

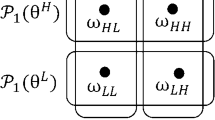

In many contest situations, such as R&D competition and rent seeking, participants’ costs are private information. We report the results of an experimental study of bidding in contests under different information and symmetry conditions about players’ costs of effort. The theory predicts qualitatively different comparative statics between bids under complete and incomplete information in contests of two and more than two players. We use a 2×3 experimental design, (n=2, n=4)×(symmetric complete information, asymmetric complete information, incomplete information), to test the theoretical predictions. We find the comparative statics of bids across the information and symmetry conditions, and the qualitative differences in comparative statics across group sizes, in partial agreement with the theory.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For example, in R&D competition, the value of the prize (patent) includes the stream of the firm’s future profits which is typically unavailable to the researcher (Fonseca 2009).

For a review of the experimental literature on contests, see Dechenaux et al. (2012). The early experiments in the complete information framework include those on simultaneous-move symmetric and asymmetric contests by Millner and Pratt (1989, 1991), Shogren and Baik (1991), Schotter and Weigelt (1992), Davis and Reilly (1998), Potters et al. (1998), Anderson and Stafford (2003), Schmidt et al. (2006). More recently, a number of experimental studies looked at more complicated contest structures such as contests with an uncertain prize (Öncüler and Croson 2005), sequential-move contests (Weimann et al. 2000; Fonseca 2009), multi-stage contests with elimination (Parco et al. 2005; Amegashie et al. 2007; Amaldoss and Rapoport 2009; Sheremeta 2010), contests with carry-overs (Schmitt et al. 2004), and multi-battle contests (Ryvkin 2009).

Thus, strictly speaking, the distribution of costs in treatments In is not continuous, and the equilibrium existence results of Fey (2008) and Ryvkin (2010) are not applicable. However, the iterative fixed-point algorithm for finding the equilibrium does converge, which can serve as a numerical proof of the existence of equilibrium in our case. Equilibrium uniqueness is still an open question.

Note that for n=2 we have b CS(c)>b I(c) for all c. This is a general result that does not require compactness of the set of possible types c i as long as the equilibrium exists (see Ryvkin 2010).

Thus, subject i’s payoff in each round is 240−c i e i if her project is successful and 120−c i e i otherwise. The parameters have been chosen so that the equilibrium bidding costs are well below the endowment for all values of c i . If c i >1, it is possible for a subject to have a negative round payoff. It happened 214 times out of the total of 15,480 observations in Part 1. Negative payoffs in paying rounds reduced subjects’ total earnings, but in the end none of the subjects had negative total earnings in Part 1.

Subjects are shown the six rounds from Part 1 and the one round from Part 2 that have been chosen randomly to base their earnings on, reminded about their payoffs in those rounds, and shown their total earnings in Parts 1 and 2.

The results from Part 4 are not used in the analysis below and are available from the authors upon request.

Part 1 of the experiment allows us to observe, on average, 276, 264, 240, 216, 288 and 264 bids per value of cost parameter c i in treatments CS2, CA2, I2, CS4, CA4 and I4, respectively. The bidding functions are constructed by calculating the average rescaled bid for each value of c in each treatment.

To test this formally, we generated variable Δb it equal to the difference between the rescaled observed bid of subject i in period t, b it , and the theoretically predicted bid in each treatment for each value of c. We then ran a regression of Δb it on all treatment dummies without the intercept for each value of c, with errors clustered by subject. The coefficients on all the treatment dummies are positive and significant at p<0.05 in all the regressions.

For each c, we ran a regression of rescaled bids, b it , on treatment dummies CS2, CA2 and I2 without the intercept, with errors clustered by subject. The hypothesis that the coefficients on all three dummies are equal cannot be rejected in all cases.

For each c, we ran a regression of b it on treatment dummies CS4, CA4 and I4 without the intercept, with errors clustered by subject. The pairwise comparisons of coefficients on the dummies reveal that for c=0.6 the average bid under CA4 is greater than under I4 (p<0.1), and for all c≥1.1 the average bids under CS4 are greater than those under CA4 and I4 (p<0.05 in all but two occasions, in which p<0.1), with no differences between the latter two.

In treatments CAn, the specification of the QRE model is more complex because a subject’s decision depends not only on her own cost, c, but also on the entire vector of other subjects’ costs, c 2,…,c n . Details are available from the authors upon request.

Details are available from the authors upon request.

Our estimates of the QRE parameter λ are similar to λ≈10 obtained by Goeree et al. (2002) for first-price auctions. In their specification, the QRE noise parameter is defined as μ=1/λ, and the maximum likelihood estimation of QRE with joy of winning under risk neutrality yields μ=0.1.

Bidding one point once in five rounds is very cheap as it only leads to expected loss of 1/5 of one cent.

A linear regression of bids in Part 2 on the cost parameter c does not produce a statistically significant slope. Other specifications, such as using a tobit regression (which is more appropriate, due to a large mass of bids at zero), a probit regression with the dependent variable equal one if b it >0 and zero otherwise, and the linear, tobit and ordered probit regressions of the number of nonzero bids, produce similar results.

Substantial bidding at the boundaries is typical for contest experiments (see a review by Sheremeta 2013). Between 9.5 % and 26.5 % of bids are zero, depending on treatment, with the highest percentage of zeros in CA4 and the lowest in I2. Between 6.1 % and 12.7 % of bids are 120 points, with the highest percentage of maximal bids in CS4 and the lowest in CA4. The mass of zero (respectively, 120) point bids increases (respectively, decreases) with the cost parameter c, as expected. Although the constraint on bids not to exceed 120 points is never binding for the Nash equilibrium predictions, it is more likely to bind for low costs in the presence of overbidding.

Random effects tobit produces very similar results, with smaller standard errors. We also ran alternative specifications with lagged bids to account for learning; the results on the treatment effects did not change.

Using c instead produces similar results. The inverse cost provides better fit as the theoretically predicted bidding functions are convex in c.

As a robustness check, we also ran a specification with interactions c×CA and c×I instead of (c>1)×CA and (c>1)×I to control for differences in the slopes of the bidding functions. The results are similar.

See Sheremeta (2013) for a detailed discussion.

Gender was identified in prior experimental studies of contests as the most important demographic factor (see a review by Sheremeta 2013). RA is measured as the number of safe options chosen by the subjects in the Holt and Laury (2002) task. It is important to control for risk aversion because bidding in contests represents choice under uncertainty and our theoretical predictions are based on risk-neutrality. We verified that subjects’ decisions in the Holt and Laury (2002) task do not depend on their earnings in Part 1 and Part 2 of the experiment.

References

Amaldoss, W., & Rapoport, A. (2009). Excessive expenditure in two-stage contests: theory and experimental evidence. In F. Columbus (Ed.), Game theory: strategies, equilibria, and theorems. Hauppauge: Nova Science Publishers

Amegashie, J., & Kutsoati, E. (2007). (Non)intervention in intra-state conflicts. European Journal of Political Economy, 23, 754–767.

Amegashie, J., Cadsby, C., & Song, Y. (2007). Competitive burnout: theory and experimental evidence. Games and Economic Behavior, 59, 213–239.

Anderson, L., & Stafford, S. (2003). An experimental analysis of rent seeking under varying competitive conditions. Public Choice, 115, 199–216.

Anderson, S., Goeree, J., & Holt, C. (1998). Rent seeking with bounded rationality: an analysis of the all-pay auction. Journal of Political Economy, 106, 828–853.

Berentsen, A., Bruegger, E., & Loertscher, S. (2008). On cheating, doping and whistle blowing. European Journal of Political Economy, 24, 415–436.

Bognanno, M. (2001). Corporate tournaments. Journal of Labour Economics, 19, 290–315.

Brueggen, A., & Strobel, M. (2007). Real effort versus chosen effort in experiments. Economics Letters, 96, 232–236.

Cason, T., Masters, W., & Sheremeta, R. (2011). Winner-take-all and proportional-prize contests: theory and experimental results. Chapman University, ESI working paper.

Chang, Y., Potter, J., & Sanders, S. (2007). War and peace: third-party intervention in conflict. European Journal of Political Economy, 23, 954–974.

Chowdhury, S., Sheremeta, R., & Turocy, T. (2012). Overdissipation and convergence in rent-seeking experiments: Cost structure and prize allocation rules. SSRN working paper available at http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2050545.

Congleton, R., Hillman, A., & Konrad, K. (Eds.) (2008). 40 years of research on rent seeking, vols 1, 2. Berlin: Springer.

Cornes, R., & Hartley, R. (2012). Risk aversion in symmetric and asymmetric contests. Economic Theory, 51, 245–275.

Dasgupta, P., & Stiglitz, J. (1980). Uncertainty, industrial structure and the speed of R&D. Bell Journal of Economics, 11, 1–28.

Dechenaux, E., Kovenock, D., & Sheremeta, R. (2012). A survey of experimental research on contests, all-pay auctions and tournaments. SSRN working paper available at http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2154022.

Davis, D., & Reilly, R. (1998). Do many cooks always spoil the stew? An experimental analysis of rent seeking and the role of a strategic buyer. Public Choice, 95, 89–115.

Ehrenberg, R., & Bognanno, M. (1990). Do tournaments have incentive effects? Journal of Political Economy, 98, 1307–1324.

Fey, M. (2008). Rent-seeking contests with incomplete information. Public Choice, 135, 225–236.

Fischbacher, U. (2007). Z-Tree: Zurich toolbox for ready-made economic experiments. Experimental Economics, 10, 171–178.

Fonseca, M. (2009). An experimental investigation of asymmetric contests. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 27, 582–591.

Gneezy, U., & Smorodinsky, R. (2006). All-pay auctions—an experimental study. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 61, 255–275.

Goeree, J., Holt, C., & Palfrey, T. (2002). Quantal response equilibrium and overbidding in private-value auctions. Journal of Economic Theory, 104, 247–272.

Greiner, B. (2004). An online recruitment system for economic experiments. In K. Kremer & V. Macho (Eds.) Forschung und wissenschaftliches Rechnen 2003. GWDG Bericht 63 (pp. 79–93). Göttingen: Ges. für Wiss. Datenverarbeitung.

Harstad, R. (1995). Privately informed seekers of an uncertain rent. Public Choice, 83, 81–93.

Hurley, T., & Shogren, J. (1998a). Asymmetric information contests. European Journal of Political Economy, 14, 645–665.

Hurley, T., & Shogren, J. (1998b). Effort levels in a Cournot-Nash contest with asymmetric information. Journal of Public Economics, 69, 195–210.

Holt, C., & Laury, S. (2002). Risk aversion and incentive effects. The American Economic Review, 92, 1644–1655.

Klemperer, P. (2004). Auctions: theory and practice. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Knoeber, C., & Thurman, W. (1994). Testing the theory of tournaments: an empirical analysis of broiler production. Journal of Labor Economics, 12, 155–179.

Konrad, K., & Kovenock, D. (2010). Contests with stochastic abilities. Economic Inquiry, 48, 89–103.

Kräkel, M. (2007). Doping and cheating in contest-like situations. European Journal of Political Economy, 23, 988–1006.

Lazear, E. (1999). Personnel economics: past lessons and future directions. Journal of Labor Economics, 17, 199–236.

Lim, W., Matros, A., & Turocy, T. (2012). Bounded rationality and group size in Tullock contests: experimental evidence. Working paper. Available at http://ihome.ust.hk/~wooyoung/index.html/lotteries-20120615.pdf.

Mago, S., Savikhin, A., & Sheremeta, R. (2012). Facing your opponents: social identification and information feedback in contests. Chapman University, ESI working paper.

Malhotra, D. (2010). The desire to win: the effects of competitive arousal on motivation and behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 111, 139–146.

Malueg, D., & Yates, A. (2004). Rent seeking with private values. Public Choice, 119, 161–178.

Malueg, D., & Yates, A. (2006). Equilibria in rent-seeking contests with homogeneous success functions. Economic Theory, 27, 719–727.

McKelvey, R., & Palfrey, T. (1995). Quantal response equilibrium for normal form games. Games and Economic Behavior, 10, 6–38.

Millner, E., & Pratt, M. (1989). An experimental investigation of efficient rent-seeking. Public Choice, 62, 139–151.

Millner, E., & Pratt, M. (1991). Risk aversion and rent seeking: an extension and some experimental evidence. Public Choice, 69, 91–92.

Niederle, M., & Vesterlund, L. (2007). Do women shy away from competition? Do men compete too much? The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 122, 1067–1101.

Noussair, C., & Silver, J. (2006). Behavior in all pay auctions with incomplete information. Games and Economic Behavior, 55, 189–206.

Öncüler, A., & Croson, R. (2005). Strategic rent seeking: an experimental investigation. Journal of Theoretical Politics, 17, 403–429.

Parco, J., Rapoport, A., & Amaldoss, W. (2005). Two-stage contests with budget constraints: an experimental study. Journal of Mathematical Psychology, 49, 320–338.

Potters, J., De Vries, C., & Van Linden, F. (1998). An experimental examination of rational rent seeking. European Journal of Political Economy, 14, 783–800.

Pogrebna, G. (2008). Learning the type of the opponent in imperfectly discriminating contests with asymmetric information. SSRN working paper available at http://ssrn.com/abstract=1259329.

Price, C., & Sheremeta, R. (2011). Endowment effects in contests. Economics Letters, 111, 217–219.

Ryvkin, D. (2009). Fatigue in dynamic tournaments. Journal of Economics and Management Strategy (forthcoming).

Ryvkin, D. (2010). Contests with private costs: beyond two players. European Journal of Political Economy, 26, 558–567.

Schmidt, D., Shupp, R., & Walker, J. (2006). Resource allocation contests: experimental evidence. CAEPR working paper, No 2006-004.

Schmitt, P., Shupp, R., Swope, K., & Cadigan, J. (2004). Multi-period rent-seeking contests with carryover: theory and experimental evidence. Economics of Governance, 5, 187–211.

Schoonbeek, L., & Winkel, B. (2006). Activity and inactivity in a rent-seeking contest with private information. Public Choice, 127, 123–132.

Schotter, A., & Weigelt, K. (1992). Asymmetric tournaments, equal opportunity laws and affirmative action: some experimental results. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 107, 511–539.

Sheremeta, R. (2010). Experimental comparison of multi-stage and one-stage contests. Games and Economic Behavior, 68, 731–747.

Sheremeta, R. (2011). Contest design: an experimental investigation. Economic Inquiry, 49, 573–590.

Sheremeta, R. (2013). Overbidding and heterogeneous behavior in contest experiments. Journal of Economic Surveys (forthcoming).

Shogren, J., & Baik, K. (1991). Reexamining efficient rent-seeking in laboratory markets. Public Choice, 69, 69–79.

Stein, W. (2002). Asymmetric rent seeking with more than two contestants. Public Choice, 113, 325–336.

Sui, Y. (2009). Rent-seeking contests with private values and resale. Public Choice, 138, 409–422.

Szymanski, S. (2003). The economic design of sporting contests: a review. Journal of Economic Literature, 41, 1137–1187.

Taylor, C. (1995). Diggin for golden carrots: an analysis of research tournaments. The American Economic Review, 85, 872–890.

Tullock, G. (1980). Efficient rent seeking. In J. Buchanan, R. Tollison, & G. Tullock (Eds.), Toward a theory of rent seeking society (pp. 97–112). Austin: Texas A&M University Press.

Wärneryd, K. (2003). Information in conflicts. Journal of Economic Theory, 110, 121–136.

Weimann, J., Yang, C., & Vogt, C. (2000). An experiment on sequential rent seeking. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 41, 405–426.

Zizzo, D. (2010). Experimenter demand effects in economic experiments. Experimental Economics, 13, 75–98.

Acknowledgements

We thank the editor, two anonymous referees, and the participants of the FSU experimental social sciences readings group, the 2010 ESA meeting in Tucson, the 2010 Australia and New Zealand workshop on experimental economics in Sydney, and the 2011 Conference on Tournaments, Contests and Relative Performance Evaluation at the North Carolina State University for their comments. Special thanks to Dan Kovenock and Roman Sheremeta for valuable discussions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Brookins, P., Ryvkin, D. An experimental study of bidding in contests of incomplete information. Exp Econ 17, 245–261 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10683-013-9365-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10683-013-9365-9