Abstract

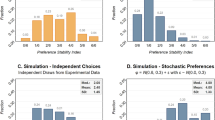

Laboratory experiments are frequently used to examine the nature of individuals’ social and risk preferences and inform economic theory. However, it is unknown whether the preferences of volunteer participants are representative of the population from which the participants are drawn, or whether they differ due to selection bias. To answer this question, we measured the preferences of 1,173 students in a classroom experiment using a trust game and a lottery choice task. Separately, we invited all students to participate in a laboratory experiment using common recruitment procedures. To evaluate whether there is selection bias, we compare the social and risk preferences of students who eventually participated in a laboratory experiment to those who did not, and find that they do not differ significantly. However, we also find that people who sent less in a trust game were more likely to participate in a laboratory experiment, and discuss possible explanations for this behavior.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

According to past university records, less than 25 percent of students sitting in this course major in Economics.

The mean number of students attending tutorials was 14 (minimum 6; maximum 18). This allowed tutors to answer questions privately and ensure that there was no communication between students during the experiment. Each tutor was given detailed, written information about the experimental procedure including precise instructions about what to say at each point of the experiment. This information can be found in the Supplementary Material.

This is similar to Falk et al. (in press) who find that 11 percent of their population volunteers for experiments.

In particular, we ran Probit regressions with robust standard errors at the level of the tutor with the dependent variable equal to 1 if the student participated in a laboratory session and equal to 0 otherwise, and treatment dummies as regressors. For every pairwise comparison we found no significant difference (p-value>0.20 in all cases) between treatments, between each treatment and the control, and between the control and the combined treatments.

Sixty-one students specified a return amount for only one of the possible actions of Player A. Past evidence using the strategy method (e.g., Garbarino and Slonim 2009) along with the current data show that the higher the amount sent by Player A, the higher the percent returned by Player B. Thus using either decision alone when subjects only indicated how much they would return for only one of the two amounts sent will be biased compared to using the average percent returned. We thus exclude from the analysis in this section observations from these 61 individuals. Our results, however, are qualitatively unaffected if we include these observations in our analysis.

Over 99 percent of the population who played the trust game (558 out of 563) gave a response for the amount sent.

The results for amount sent and percent returned are qualitatively the same if we run a single regression for all three decisions in the trust game (i.e., amount sent, percent returned if sent $10, percent returned if sent $20).

Participants who chose Lottery 1 and Lottery 6 were not more likely to self-select into the lab when independently compared to all other participants which suggests that this result is not caused by oversampling of the tails of the distribution of risk preferences.

As noted, Falk et al. (in press) find no evidence that social preferences affect selection in laboratory experiments. Slonim et al. (2012) find amongst other results that individuals who donate more money to a charity in high-stake Dictator Game are (marginally) significantly more likely to attend a laboratory experiment the following week. At the same time, however, these authors find that individuals who donate more to charity in their daily lives (self-reported amounts) are not more likely to participate in lab experiments.

References

Bardsley, N., Cubitt, R., Loomes, G., Moffatt, P., Starmer, C., & Sugden, R. (2009). Experimental economics: rethinking the rules. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Berg, J., Dickhaut, J., & McCabe, K. (1995). Trust, reciprocity, and social history. Games and Economic Behavior, 10(1), 122–142.

Binswanger, H. P. (1981). Attitudes toward risk: theoretical implications of an experiment in rural India. Economic Journal, 91, 867–890.

Bohnet, I., & Zeckhauser, R. (2004). Trust, risk and betrayal. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 55(5), 467–484.

Cleave, B. L., Nikiforakis, N., & Slonim, R. (2010). Is there selection bias in laboratory experiments? (Research Paper No. 1106). Dept. Economics, University of Melbourne.

Eckel, C., & Grossman, P. (2008). Forecasting risk attitudes: an experimental study using actual and forecast gamble choices. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 68(1), 1–17.

Falk, A., Meier, S., & Zehnder, C. (in press). Do lab experiments misrepresent social preferences? The case of self-selected student samples. Journal of the European Economic Association.

Garbarino, E., & Slonim, R. (2009). The robustness of trust & reciprocity across a heterogeneous population. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 69(3), 226–240.

Harrison, G. W., Lau, M., & Rutström, E. (2009). Risk attitudes, randomization to treatment, and self-selection into experiments. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 70, 498–507.

Levitt, S. D., & List, J. A. (2007). What do laboratory experiments measuring social preferences reveal about the real world. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 21(2), 153–174.

Slonim, R., Wang, C., Garbarino, E., & Merrett, D. (2012). Opting-in: participation biases in the lab (IZA Discussion Paper No. 6865).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

We thank the Editor (David Cooper), two anonymous referees, Jim Andreoni, Tim Cason, Marco Casari, Gary Charness, Rachel Croson, Dirk Engelmann, Ernst Fehr, Simon Gächter, Glenn Harrison, Stephen Leider, John List, Simon Loertscher, Joerg Oechssler and participants at the 2010 Asia-Pacific Meetings of the Economic Science Association at the University of Melbourne, IMEBE 2010 in Bilbao, THEEM 2010 in Thurgau and seminar participants at the University of Mannheim, University of Melbourne, Monash University, the University of Zürich, the Athens University of Economics and Business, the University of Athens, Royal Holloway University of London for comments. We also thank Jeff Borland who allowed us to run the experiment in his class, Nahid Khan who helped coordinate tutors and Viktoriya Koleva for helping to prepare the experimental material. Funding from the Faculty of Business and Economics at the University of Melbourne and the Faculty of Economics and Business at the University of Sydney is gratefully acknowledged.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cleave, B.L., Nikiforakis, N. & Slonim, R. Is there selection bias in laboratory experiments? The case of social and risk preferences. Exp Econ 16, 372–382 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10683-012-9342-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10683-012-9342-8