Abstract

This paper is based on the assumption that divorced and separated individuals bring with them the experience of a failed union which may shape their future choices on the marriage market. It aims to contribute to our knowledge of intermarriage, and social interaction in Sweden in general, by comparing the repartnering choices of immigrants and natives in Sweden who had made what is still considered an atypical choice of entering a native-immigrant union with the partner choices of natives and immigrants whose previous union was endogamous. The empirical analysis in this paper is based on the Swedish register data from the STAR data collection (Sweden over Time: Activities and Relations) and covers the period 1990–2007. All the analyses in the paper include individuals aged 20–55 at the time of union dissolution. The multivariate analysis is based on discrete-time multinomial logistic regression. The results show that for all four groups defined by sex and nativity (native men, native women, immigrant men, and immigrant women), there is a positive association between the previous experience of intermarriage and the likelihood of initiating another intermarriage after union dissolution. Another important finding is that the magnitude of this positive association increases with the degree of social distance between the groups involved in the union. Gender differences are modest among natives and somewhat more pronounced among immigrants.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The repartnering patterns of second-generation immigrants (i.e., Swedish-born individuals with at least one foreign-born parent) are not dealt with in this paper. Second-generation immigrants, however, do constitute a separate group in the partner classification.

Throughout this paper, the term “type of union” is used to refer to the type of union with respect to the partner’s origin.

The basic idea is to define co-ethnics as two individuals belonging to the same immigrant group, by which country of birth would be the main criterion for defining these groups. However, due to the classification of country of origin in the registers used for this research, it is only possible to identify country of birth for the most significant sending countries, while other immigrants are considered co-ethnics if they belong to the same panethnicity (i.e., if they were born in the same region of the world). Nevertheless, it is safe to assume that in a majority of endogamous unions defined by panethnicity the partners were actually born in the same country [see descriptive evidence based on 138 individual countries of birth in Dribe and Lundh (2011)]. The classification of immigrant groups is shown in Table 3 in Appendix. It should also be noted that a foreign-born individual and a second-generation immigrant are not considered co-ethnics in this paper, regardless of the parental country of birth of the second-generation immigrant.

For instance, in the models for natives, interaction Western immigrants stands for previous partner Western immigrant*share of Western immigrants in the municipality.

The inclusion of time-varying marriage market indicators entails a certain degree of threat of reverse causality. For instance, a native person who wants to repartner with a foreign-born person residing in a neighborhood with a high immigrant presence may move to a future partner’s municipality before the year of formation of the new union. Therefore, additional analyses were performed in which marriage market indicators are time-invariant and refer to the year of union dissolution and the municipality where the individual at risk of repartnering lived that year. However, the alternative approach does not change the overall findings.

This variable refers to union dissolutions experienced in Sweden. The registers have no information about immigrants’ pre-migration partnership history.

Models with dummies for each immigrant group failed to converge due to a very small number of cases for some of these groups.

The number of actual events by the type of previous and subsequent union is shown in Tables S1 and S2 in the Online Supplement.

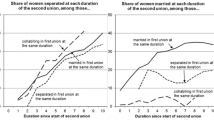

Note that the panels are scaled differently for better visibility.

For the sake of space, the results on other characteristics of previous union, local marriage markets and, in the case of immigrants, geographical origin are not reported in Tables A2–A3 and are thus not discussed in this section. However, these results can be obtained upon request.

References

Adserà, A., & Ferrer, A. (2014). Immigrants and demography: Marriage, divorce, and fertility. IZA Discussion Paper Series No. 7982. Bonn: Institute for the Study of Labor.

Agell, A., & Brattström, M. (2008). Äktenskap, samboskap, partnerskap [marriage, cohabitation, partnership] (4th ed.). Uppsala: Iustus förlag.

Aguirre, B. E., Saenz, R., & Hwang, S.-S. (1995). Remarriage and intermarriage of Asians in the United States of America. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 26(2), 207–215.

Alba, R. D., & Golden, R. M. (1986). Patterns of ethnic marriage in the United States. Social Forces, 65(1), 202–223.

Andersson, G. (1998). Trends in marriage formation in Sweden 1971–1993. European Journal of Population/Revue européenne de Démographie, 14(2), 157–178.

Andersson, G. (2004). Children’s experience of family disruption and family formation: Evidence from 16 FFS countries. Vienna Yearbook of Population Research, 2, 313–332.

Andersson, G., & Philipov, D. (2002). Life-table representations of family dynamics in Sweden, Hungary, and 14 other FFS countries: A project of descriptions of demographic behavior. Demographic Research, 7(4), 67–144.

Blau, P. M., Beeker, C., & Fitzpatrick, K. M. (1984). Intersecting social affiliations and intermarriage. Social Forces, 62(3), 585–606.

Blau, P. M., Blum, T. C., & Schwartz, J. E. (1982). Heterogeneity and intermarriage. American Sociological Review, 47(1), 45–62.

Bogardus, E. S. (1925). Measuring social distance. Journal of Applied Sociology, 9, 299–308.

Booth, A., & Edwards, J. N. (1992). Starting over why remarriages are more unstable. Journal of Family Issues, 13(2), 179–194.

Bratter, J. L., & King, R. B. (2008). But will it last? Marital instability among interracial and Same-Race couples. Family Relations, 57(2), 160–171.

Bustamante, R. M., Nelson, J. A., Henriksen, R. C., & Monakes, S. (2011). Intercultural couples: Coping with culture-related stressors. The Family Journal, 19(2), 154–164.

Chiswick, B. R., & Houseworth, C. (2011). Ethnic intermarriage among immigrants: Human capital and assortative mating. Review of Economics of the Household, 9(2), 149–180.

Choi, K. H., Tienda, M., Cobb-Clark, D., & Sinning, M. (2012). Immigration and status exchange in Australia and the United States. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 30(1), 49–62.

Coviello, V., & Boggess, M. (2004). Cumulative incidence estimation in the presence of competing risks. STATA Journal, 4, 103–112.

Darvishpour, M. (2002). Immigrant women challenge the role of men: How the changing power relationship within Iranian families in Sweden intensifies family conflicts after immigration. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 33(2), 271–296.

De Graaf, P. M., & Kalmijn, M. (2003). Alternative routes in the remarriage market: Competing-risk analyses of union formation after divorce. Social Forces, 81(4), 1459–1498.

Dean, G., & Gurak, D. T. (1978). Marital homogamy the second time around. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 40(3), 559–570.

Dewilde, C., & Uunk, W. (2008). Remarriage as a way to overcome the financial consequences of divorce—A test of the economic need hypothesis for European women. European Sociological Review, 24(3), 393–407.

Dribe, M., & Lundh, C. (2008). Intermarriage and immigrant integration in Sweden an exploratory analysis. Acta Sociologica, 51(4), 329–354.

Dribe, M., & Lundh, C. (2011). Cultural dissimilarity and intermarriage. A longitudinal study of immigrants in Sweden 1990–2005. International Migration Review, 45(2), 297–324.

Dribe, M., & Lundh, C. (2012). Intermarriage, value context and union dissolution: Sweden 1990–2005. European Journal of Population/Revue européenne de Démographie, 28(2), 139–158.

Duvander, A.-Z. E. (1999). The transition from cohabitation to marriage—A longitudinal study of the propensity to marry in Sweden in the early 1990s. Journal of Family Issues, 20(5), 698–717.

Feng, Z., Boyle, P., van Ham, M., & Raab, G. M. (2012). Are mixed-ethnic unions more likely to dissolve than co-ethnic unions? New evidence from Britain. European Journal of Population/Revue européenne de Démographie, 28(2), 159–176.

Fu, V. K. (2001). Racial intermarriage pairings. Demography, 38(2), 147–159.

Fu, V. K. (2010). Remarriage, delayed marriage, and Black/White intermarriage, 1968–1995. Population Research and Policy Review, 29(5), 687–713.

Furtado, D., & Theodoropoulos, N. (2011). Interethnic marriage: A choice between ethnic and educational similarities. Journal of Population Economics, 24(4), 1257–1279.

Furtado, D., & Trejo, S. (2012). Interethnic marriages and their economic effects. IZA Discussion Paper Series No. 6399. Bonn: Institute for the Study of Labor.

Gelissen, J. (2004). Assortative mating after divorce: A test of two competing hypotheses using marginal models. Social Science Research, 33(3), 361–384.

Glenn, N. D. (1982). Interreligious marriage in the United States: Patterns and recent trends. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 44(3), 555–566.

González-Ferrer, A. (2006). Who do immigrants marry? Partner choice among single immigrants in Germany. European Sociological Review, 22(2), 171–185.

Gordon, M. M. (1964). Assimilation in American life: The role of race, religion and national origins. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Haandrikman, K. (2014). Binational marriages in Sweden: Is there an EU effect? Population, Space and Place, 20(2), 177–199.

Hohmann-Marriott, B. E., & Amato, P. (2008). Relationship quality in interethnic marriages and cohabitations. Social Forces, 87(2), 825–855.

Holland, J. A. (2012). Home and where the heart is: Marriage timing and joint home purchase. European Journal of Population/Revue européenne de Démographie, 28(1), 65–89.

Hwang, S.-S., Saenz, R., & Aguirre, B. E. (1997). Structural and assimilationist explanations of Asian American intermarriage. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 59(3), 758–772.

Inglehart, R. (1997). Modernization and postmodernization: Cultural, economic, and political change in 43 societies. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ Press.

Jacobs, J. A., & Furstenberg, F. F. (1986). Changing places: Conjugal careers and women’s marital mobility. Social Forces, 64(3), 714–732.

Jones, F. L. (1996). Convergence and divergence in ethnic divorce patterns: A research note. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 58(1), 213–218.

Kalmijn, M. (1993). Trends in black/white intermarriage. Social Forces, 72(1), 119–146.

Kalmijn, M. (1998). Intermarriage and homogamy: Causes, patterns, trends. Annual Review of Sociology, 24, 395–421.

Kalmijn, M., de Graaf, P. M., & Janssen, J. P. (2005). Intermarriage and the risk of divorce in the Netherlands: The effects of differences in religion and in nationality, 1974–94. Population Studies, 59(1), 71–85.

Kalmijn, M., & Flap, H. (2001). Assortative meeting and mating: Unintended consequences of organized settings for partner choices. Social Forces, 79(4), 1289–1312.

Kalmijn, M., Liefbroer, A. C., Van Poppel, F., & Van Solinge, H. (2006). The family factor in Jewish-Gentile intermarriage: A sibling analysis of the Netherlands. Social Forces, 84(3), 1347–1358.

Kalmijn, M., & Van Tubergen, F. (2006). Ethnic intermarriage in the Netherlands: Confirmations and refutations of accepted insights. European Journal of Population/Revue européenne de Démographie, 22(4), 371–397.

Kiernan, K. (2001). The rise of cohabitation and childbearing outside marriage in Western Europe. International Journal of Law, Policy and the Family, 15(1), 1–21.

Kolk, M. (2012). Age differences in Unions - Continuity and divergence in Sweden between 1932 and 2007. Stockholm Research Reports in Demography, 25, 1–37.

Kulu, H., & González-Ferrer, A. (2014). Family dynamics among immigrants and their descendants in Europe: Current research and opportunities. European Journal of Population, 30(4), 411–435.

Lanzieri, G. (2012). A look at marriages with foreign-born persons in European countries. Eurostat: Statistics in Focus 29/2012.

Lehrer, E. L. (1998). Religious intermarriage in the United States: Determinants and trends. Social Science Research, 27(3), 245–263.

Lievens, J. (1998). Interethnic marriage: Bringing in the context through multilevel modelling. European Journal of Population/Revue européenne de Démographie, 14(2), 117–155.

Lucassen, L., & Laarman, C. (2009). Immigration, intermarriage and the changing face of Europe in the post war period. The History of the Family, 14(1), 52–68.

Lyngstad, T. H., & Jalovaara, M. (2010). A review of the antecedents of union dissolution. Demographic Research, 23(10), 257–292.

Medrano, J. D., Cortina, C., Safranoff, A., & Castro-Martín, T. (2014). Euromarriages in Spain: Recent trends and patterns in the context of European integration. Population, Space and Place, 20(2), 157–176.

Milewski, N., & Kulu, H. (2014). Mixed marriages in Germany: A high risk of divorce for immigrant-native couples. European Journal of Population/Revue européenne de Démographie, 30(1), 89–113.

Muttarak, R., & Heath, A. (2010). Who intermarries in Britain? Explaining ethnic diversity in intermarriage patterns. The British Journal of Sociology, 61(2), 275–305.

O’Leary, R., & Finnäs, F. (2002). Education, social integration and minority-majority group intermarriage. Sociology, 36(2), 235–254.

Pagnini, D. L., & Morgan, S. P. (1990). Intermarriage and social distance among US immigrants at the turn of the century. American Journal of Sociology, 96(2), 405–432.

Perelli-Harris, B., & Gassen, N. S. (2012). How similar are cohabitation and marriage? Legal approaches to cohabitation across Western Europe. Population and Development Review, 38(3), 435–467.

Pettigrew, T. F., & Tropp, L. R. (2008). How does intergroup contact reduce prejudice? Meta-analytic tests of three mediators. European Journal of Social Psychology, 38(6), 922–934.

Qian, Z. (1997). Breaking the racial barriers: Variations in interracial marriage between 1980 and 1990. Demography, 34(2), 263–276.

Qian, Z., & Lichter, D. T. (2001). Measuring marital assimilation: Intermarriage among natives and immigrants. Social Science Research, 30(2), 289–312.

Qian, Z., & Lichter, D. T. (2007). Social boundaries and marital assimilation: Interpreting trends in racial and ethnic intermarriage. American Sociological Review, 72(1), 68–94.

Sánchez-Domínguez, M., De Valk, H., & Reher, D. (2011). Marriage strategies among immigrants in Spain. Revista Internacional De Sociología, 69(M1), 139–166.

Sherkat, D. E. (2004). Religious intermarriage in the United States: Trends, patterns, and predictors. Social Science Research, 33(4), 606–625.

Smith, S., Maas, I., & van Tubergen, F. (2012). Irreconcilable differences? Ethnic intermarriage and divorce in the Netherlands, 1995–2008. Social Science Research, 41(5), 1126–1237.

Smits, J. (2010). Ethnic intermarriage and social cohesion. What can we learn from Yugoslavia? Social Indicators Research, 96(3), 417–432.

Sweeney, M. M. (1997). Remarriage of women and men after divorce the role of socioeconomic prospects. Journal of Family Issues, 18(5), 479–502.

Tolsma, J., Lubbers, M., & Coenders, M. (2008). Ethnic competition and opposition to ethnic intermarriage in the Netherlands: A multi-level approach. European Sociological Review, 24(2), 215–230.

Tucker, M. B., & Mitchell-Kernan, C. (1990). New trends in black American interracial marriage: The social structural context. Journal of Marriage and Family, 52(1), 209–218.

Van Tubergen, F., & Maas, I. (2007). Ethnic intermarriage among immigrants in the Netherlands: An analysis of population data. Social Science Research, 36(3), 1065–1086.

Vikat, A., Thomson, E., & Hoem, J. M. (1999). Stepfamily fertility in contemporary Sweden: The impact of childbearing before the current union. Population Studies, 53(2), 211–225.

Whyte, M. K. (1990). Dating, mating, and marriage. Hawthorne, NY: Aldine de Gruyter.

Wiik, K. A., Bernhardt, E., & Noack, T. (2009). A study of commitment and relationship quality in Sweden and Norway. Journal of Marriage and Family, 71(3), 465–477.

Wu, Z., & Schimmele, C. M. (2005). Repartnering after first union disruption. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67(1), 27–36.

Zantvliet, V., Pascale, I., Kalmijn, M., & Verbakel, E. (2014). Parental involvement in partner choice: The case of Turks and Moroccans in the Netherlands. European Sociological Review, 30(3), 387–398.

Zhang, Y., & Van Hook, J. (2009). Marital dissolution among interracial couples. Journal of Marriage and Family, 71(1), 95–107.

Acknowledgments

Financial support from the Swedish Research Council (Vetenskapsrådet) via the Swedish Initiative for Research on Microdata in the Social and Medical Sciences (SIMSAM): Stockholm University SIMSAM Node for Demographic Research (Grant Registration Number 340-2013-5164), and the Linnaeus Center on Social Policy and Family Dynamics in Europe (SPaDE) (Grant 349-2007-8701) is gratefully acknowledged. I would also like to thank Juho Härkönen, Gunnar Andersson as well as reviewers and editors of the European Journal of Population for valuable comments and suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Obućina, O. Partner Choice in Sweden Following a Failed Intermarriage. Eur J Population 32, 511–542 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-016-9377-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-016-9377-1