Abstract

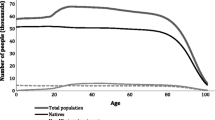

Will future immigration to a country with a large public sector alleviate the increasing burden on the public welfare system due to an ageing population? The question is based on the experience that the age structure of immigrants differs from that of the native population. Fiscal impacts due to immigration depend mainly on the size, the age composition and the labour market integration of the additional population which arises because of immigration. A projection from Statistics Sweden about future immigration combined with the latest Long-Term Survey of the Swedish Economy has been used in this study. Calculations for Sweden up to the year 2050 show that the positive net contribution to the public sector from the additional population is rather small even with good integration into the labour market. The reason is that future immigration will increase the size of the population and thereby raise not only revenue from taxation but also public expenses. The fiscal impact is sensitive to the labour market integration of the additional population. The yearly positive/negative net contribution effect is less than 1% of GDP for most of the years. On the whole, the results are about the same even if we change the assumptions concerning the composition of future public revenues, the growth of public expenses, return migration, or the age-specific birth and death rates in the additional population. More considerable net fiscal effects would require a much higher and probably unrealistic level of future immigration.

Résumé

L’immigration future dans un pays disposant d’un vaste secteur public soulagera-t-elle le poids que le vieillissement démographique fait peser sur le système public de sécurité sociale ? La question se base sur le fait que la structure par âge des immigrants diffère de celle de la population autochtone. L’impact fiscal de l’immigration dépend principalement de l’importance numérique, de la structure par âge et de l’intégration dans le marché du travail de la population additionnelle qui survient du fait de l’immigration. Une projection relative à l’immigration future réalisée par Statistiques Suède combinée aux données de la dernière enquête de longue durée sur l’économie suédoise a été utilisée pour cette étude. Les projections jusqu’en 2050 montrent que la contribution positive nette de la population additionnelle au secteur public est plutôt faible même dans le cas d’une bonne intégration dans le marché du travail. Ceci est dû au fait que l’immigration future augmentera l’effectif de la population, accroissant ainsi les revenus issus des taxes mais aussi les dépenses publiques. L’impact fiscal est sensible au degré d’intégration de la population additionnelle dans le marché du travail. La contribution annuelle nette positive/négative est inférieure à 1% du PIB pour la plupart des années considérées. Dans l’ensemble, les résultats restent semblables quelles que soient les hypothèses relatives à la composition des recettes publiques futures, à la croissance des dépenses publiques, aux migrations de retour et aux taux de natalité et de mortalité par âge de la population additionnelle. Des effets fiscaux plus élevés nécessiteraient des niveaux d’immigration future beaucoup plus élevés et sans doute irréalistes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

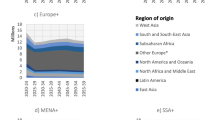

In reality, Statistics Sweden (2006) made two forecasts of future immigration. There is one basic alternative and one alternative with higher immigration. The basic alternative corresponds to a yearly net immigration (difference between immigration and outmigration) of 12,000–15,000 individuals. It is not realistic to use a basic alternative with no net immigration at all because this alternative also includes native-born Swedes who return home. In the high immigration alternative, the yearly net immigration is about 35,000 individuals. By future immigration we mean the difference between the high immigration alternative and the basic alternative. The additional population is a projection of this difference considering age-specific fertility rates, age-specific death rates and return migration. The original population is a projection of the rest (the majority) of the population. Thus the original population also includes the immigrants already living in Sweden 2006.

There are also public investments but they amounted to only about 5% of public expenses in 2006. Besides, a large share of public investment is not financed by taxes but by loans. Therefore, we limit public expenses to public transfer payments and public consumption expenditures.

For example the proportions will be 34.3, 7.9, 32.4 and 25.4% in 2020; 34.4, 7.6, 32.7 and 25.3% in 2030; 34.4, 7.4, 32.7 and 25.5% in 2040; 34.3, 7.6, 32.2 and 25.8% in 2050. For 2015 we have used the average of the proportions in 2006 and 2020. For 2025 the average of the proportions in 2020 and in 2030 has been used. For 2035 the average of the proportions in 2030 and in 2040 has been used.

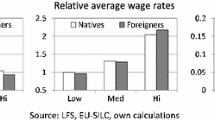

The age-specific employment rates can differ between different immigrant groups. We assume that, on average, the age-specific employment rates are the same in the additional population as in the original population. In the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s, when the labour market situation was good for immigrants in Sweden, the age-specific employment rates were practically the same for different immigrant groups and for refugees.

We assume that the capital intensity (capital per unit labour) is the same as in case 1. This means that for a Cobb-Douglas production function with constant return to scale the GDP decreases in proportion to the decreases in the total number of employed in the economy. The effect on GDP will be rather small because the number employed in the additional population is a small part of the number employed in the total population.

References

Akbari, A. H. (1989). The benefits of immigrants to Canada: Evidence on tax and public services. Canadian Public Policy, 15(4), 424–435.

Albin, B., Ekberg, J., Elmeståhl, S., & Hjelm, K. (2005). Mortality among foreign-born and native-born Swedes. European Journal of Public Health, 15(5), 511–517.

Ben-Gad, M. (2004). The economic effects of immigration—a dynamic analysis. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, 28(9), 1825–1845.

Blau, F. D. (1984). The use of transfer payments by immigrants. International Labour Relations Review, 37(2), 222–239.

Bonin, H., Raffelhuschen, B., & Walliser, J. (2000). Can immigration alleviate the demographic burden? FinanzArchiv, 57(1), 1–21.

Borjas, G. J. (1994). The economics of immigration. Journal of Economic Literature, 32(4), 1616–1717.

Coleman, D. (2008). The demographic effects of international migration in Europe. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 24(3), 453–477.

Coleman, D., & Rowthorn, R. (2004). Effects of immigration into the United Kingdom. Population and Development Review, 30(4), 579–622.

Ekberg, J. (1983). Inkomsteffekter av invandring. (Income effects due to immigration). PhD– thesis in Economics Lund University. Lund Economic Studies, no 27. Lund. (Summary in English).

Ekberg, J. (1999). Immigration and the public sector. Income effects for the native population in Sweden. Journal of Population Economics, 12(3), 411–430.

Ekberg, J. (2009). Invandringen och de offentliga finanserna [Immigration and the public finances]. Rapport 2009:3 to the Expert group for public finances (ESO). Stockholm: The Ministry of Finance (Summary in English).

Ekberg, J. (2010). Effekter för offentliga finanser vid alternativa scenarier beträffande framtida invandring (Effects on public finances with alternatives scenarios of future immigration). Paper. Vaxjo: Linnaeus University.

Ekberg, J., & Rooth, D-O. (2001). Är invandrare oprioriterade inom arbetsmarknadspolitiken? (Are immigrants not giving priority to labour market policy programmes?). Ekonomisk Debatt, 28(4), 285–291.

Försäkringskassan. (2007). Socialförsäkringsboken 2006 (Social security book 2006). Social Insurance Agency: Stockholm.

Gieseck, A., Heilemann, V., & Loeffelholz, H. (1994). Economic implications of migration into the Federal republic of Germany 1988–1992. In S. Spencer (Ed.), Immigration as an economic asset. Staffordshire: Trentham books.

Gustafsson, B. (1990). Public sector transfers and income taxes among immigrants and natives in Sweden. International Migration, 28(2), 181–200.

Gustafsson, B., & Österberg, T. (2001). Immigrants and the public sector-accounting exercises for Sweden. Journal of Population Economics, 14(4), 689–708.

Kakwani, N. (1986). Analysing redistribution policies. A study using Australian data. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Korpi, M. (2008). Migration and wage inequality: economic effects of migration to and within Sweden 1993–2003. Working Paper Series no 2008:13. Stockholm: Institute for future studies.

Lee, R. D., & Miller, T. (2000). Immigration, social security and broader fiscal impacts. American Economic Review, 90(2), 350–354.

Longhi, S., Nijkamp, P., & Poot, J. (2005). A meta–analytic assessment of the effect of immigration on wages. Journal of Economic Surveys, 19(5), 451–477.

Longhi, S., Nijkamp, P., & Poot, J. (2006). The fallacy of ‘job robing’: a meta-analysis of estimates of the effect of immigration on employment. Journal of Migration and Refugee Issues, 1(4), 131–152.

Longhi, S., Nijkamp. P., & Poot, J. (2008). Meta–analysis of empirical evidence on the labour market impacts of immigration. Discussion Paper Series no 3418. Bonn: The Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA).

Lutz, W., Marmolo, M., & Scherbov, S. (2008). Probabilistic population projections for the 27 EU member states. Paper at 2008 European population Conference, 9–12 July Barcelona. Spain.

Ministry of Finance. (1990). The medium term survey of the Swedish economy. SOU 1990:14. Stockholm: Allmänna Förlaget.

Ministry of Finance. (2008a). Långtidsutredningen 2008. (Long term survey of the Swedish economy 2008). SOU 2008:105. Stockholm: Fritzes.

Ministry of Finance. (2008b). Scenarier på lång sikt. Bilaga 1 till långtidsutredningen 2008 (Scenarios in the long run. Supplement 1 to the Long term survey of the Swedish economy 2008). SOU 2008: 108. Stockholm: Fritzes.

Ohlsson, R. (1975). Invandrarna på arbetsmarknaden (Immigrants in the labour market). PhD-thesis in Economic History. Ekonomisk-historiska Föreningen, (Vol. XVI). Lund: Lund University (Summary in English).

Pedersen, L. H. (2002). Ageing, immigration and fiscal sustainability. Copenhagen, mimeo: DREAM.

Poot, J. & Cochrane, B. (2005). Measuring the economic impact of immigration: A scoping paper. Discussion Paper no 48. Hamilton: Population Studies Centre, The University of Waikato.

Rowthorn, R. (2008). The Fiscal impact of immigration on the advanced economies. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 24(3), 561–589.

Schou, P. (2006). Immigration, integration and fiscal sustainability. Journal of Population Economics, 19(4), 671–689.

Simon, J. (1984). Immigrants, taxes and welfare in the United States. Population and Development Review, 10(1), 55–69.

Statistic Sweden. (1975). Sveriges befolkningsutveckling (The population development of Sweden). Information i prognosfrågor 1975:6. Stockholm.

Statistic Sweden. (2002b). Invandring—en lösning på försöjningsbördan? (Immigration—a solution on increasing dependency ratio?). Demografiska rapporter 2002:6. Stockholm.

Statistic Sweden. (2009). Sveriges framtida befolkning (The future population of Sweden). Demografiska rapporter 2009:1. Stockholm.

Statistics Sweden. (2002a). Kapital inkomster (Incomes from capital) Inkopak 2002. Stockholm.

Statistics Sweden. (2004). Efterkrigstidens invandring och utvandring (Immigration and emigration during the postwar period). Demografiska rapporter 2004:5. Stockholm.

Statistics Sweden. (2006). Sveriges framtida befolkning 2006–2050 (The future population in Sweden 2006–2050). Demografiska rapporter 2006:2. Stockholm.

Statistics Sweden (2007) Arbetskraftsundersökningarna 2006 (Labour force surveys 2006). Stockholm.

Statistics Sweden. (2008a). Specialbeställd data över inkomster, skatter och offentliga transfereringar år 2006 för infödda och utrikes födda (Specially delivered data about incomes, taxes and public transfers in 2006 for native–born and foreign–born). Stockholm.

Statistics Sweden. (2008b). Barnafödandet bland inrikes och utrikes födda (Childbearing among natives and foreign–born). Demografiska rapporter 2008:2. Stockholm.

Statistics Sweden. (2010a). Födda i Sverige men ändå olika. Betydelsen av föräldrarnas födelseland (Born in Sweden-but still different? The significance of parents country of birth). Demografiska rapporter 2010:2. Stockholm.

Statistics Sweden. (2010b). Arbetskraftsundersökningarna 2009 (Labour force surveys 2009). Stockholm.

Statistics Sweden. (2010c). Arbetskraftsundersökningarna andra kvartalet 2010 (Labour force surveys the second quarter of 2010). Stockholm.

Storesletten, K. (2003). Fiscal implications of immigration to Sweden—a net present value calculation. Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 105(3), 487–506.

Straubhaar, T., & Weber, R. (1994). On the economics of immigration: some empirical evidence for Switzerland. International Review of Applied Economics, 8(2), 107–129.

The Swedish Audit Bureau (2007). Regeringens analys av finanspolitikens långsiktiga hållbarhet. (The Government’s analysis of long run persistency of finance policy). Rapport RIR 2007.21. Stockholm.

Ulrich, R. (1994). The impact of foreigners on public purse. In S. Spencer (Ed.), Immigration as an economic asset. Staffordshire: Trentham Books.

Wadensjö, E. (1973). Immigration och samhällsekonomi. (Immigration and economy). PhD– thesis in Economics Lund University. Lund Economic Studies no 8. Lund. (Summary in English).

Wadensjö, E. (2000). Omfördelning genom offentlig sektor: En fördjupad analys. (Redistribution through public sector. A deeper analysis). In Mogensen G (ed.) Integration i Danmark omkring årtusendskiftet. (Integration in Denmark around the turn of millennium). Aarhus: Aarhus universitetsforlag.

Wadensjö, E., & Orrje, H. (2002). Immigration and the public sector in Denmark. Aarhus: Aarhus universitetsforlag.

Weintraub, S. (1984). Illegal immigrants in Texas: impact on social services and related considerations. International Migration Review, 18(3), 733–747.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to the Expert Group on Public Finance (ESO) at the Ministry of Finance, Sweden, for financial support of this study. I am also grateful for useful comments and suggestions from two anonymous referees and from the editor, from ESO’s reference group, from Ali Ahmed and Lennart Delander Linnaeus University Växjö, and from Christer Gerdes Stockholm University and Martin Ådahl Fores. Besides I am grateful to Annika Klintefelt, Petter Lundborg, Hans Lundström and Petter Wikström at Statistics Sweden for excellent data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

See Table 6.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ekberg, J. Will Future Immigration to Sweden Make it Easier to Finance the Welfare System?. Eur J Population 27, 103–124 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-010-9227-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-010-9227-5