Abstract

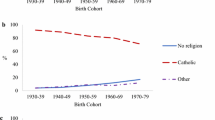

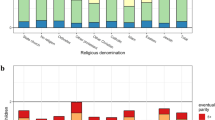

Although previous studies have demonstrated that religious people in Europe have larger families, the role played by religious socialisation in the context of contemporary fertility behaviour has not yet been analysed in detail. This contribution specifically looks at the interrelation between religious socialisation and current religiosity and their impact on the transition to the third child for Dutch women. It is based on data of the first wave of the Netherlands Kinship Panel Study (2002–2004) and uses event history analysis. The transitions to first, second and third birth are modelled jointly with a control for unobserved heterogeneity. The findings provide evidence for an impact of women’s current church attendance as well as religious socialisation measured by their fathers’ religious affiliation, when they were teenagers. A religious family background remains influential even when a woman has stopped attending church. The effects of religious indicators strengthen over cohorts. Moreover, the combined religious make-up of the respondent’s parents also significantly determines the progression to the third child.

Résumé

S’il est bien établi que les croyants en Europe ont plus d’enfants que les autres, le rôle de la socialisation religieuse dans le contexte de la fécondité contemporaine n’a pas encore été analysé à ce jour. Cette étude s’intéresse au lien entre la socialisation religieuse et la religiosité actuelle, et à leur impact sur la probabilité d’agrandissement de deux à trois enfants de la descendance des femmes néerlandaises. Les données exploitées sont celles de la première vague du Panel Néerlandais d’Etude de la Parenté (the Netherlands Kinship Panel Study, 2002–2004). A l’aide des techniques de l’analyse des biographies, les probabilités d’agrandissement de rang 1, rang 2 et rang 3 ont été modélisées de façon conjointe, en contrôlant l’hétérogénéité non observée. Les résultats mettent en évidence l’impact de la fréquentation actuelle de l’église par les femmes et de leur socialisation religieuse, mesurée par l’appartenance religieuse de leur père quand elles étaient adolescentes. Il apparaît que la religiosité du contexte familial exerce une influence, même quand la femme ne fréquente plus l’église, et que les effets des indicateurs de pratique religieuse se renforcent d’une génération à l’autre. Enfin, l’appartenance religieuse conjointe des parents de la femme détermine significativement la probabilité d’avoir un troisième enfant.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Among the non-Christian religions in the Netherlands, the most numerous adherents are Muslims, comprising about 5.8% of the population in 2005, and Hindus who amount to about 0.6%. Both religions registered marked increases during the previous decades. For instance, in 1980, they had represented 1.7% and 0.2% of the Dutch population, respectively (Becker and de Hart 2006, p. 34).

The Dutch Reformed Church (Nederlandse Hervormde Kerk) was the main church that originated from the reformation in the sixteenth century. Two important secessions of conservative streams took place in the nineteenth century. Most of the secessionists confederated and founded the Reformed Churches in the Netherlands (Gereformeerde Kerken in Nederland) in 1892, further denoted as Calvinists.

The respondents were divided into three categories (young, middle and old) in the proportion 1:2:1. Young women were defined as those aged 16–23 at the birth of their first child, middle-aged women as those 24–29 and old women as those aged 30–41 years when they had their first child.

The constructed time intervals are 0–1, 2, 3, 4 and 5+ years.

The respondents were assigned to the following birth cohorts: 1937–1944, 1945–1954, 1955–1964 and 1965–1979.

The levels of education were constructed according to the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED). Completed or incomplete elementary school (ISCED 1), lower vocational and lower general schooling between ages 12–15 or 16, respectively (ISCED 2) were defined as low education. Intermediate education comprises completed intermediate general secondary, upper general secondary and intermediate vocational training between ages 15/16 and 17–20 (ISCED 3). High education refers to women who accomplished their higher vocational, university or post-graduate training taking place between ages 17/18 to 20–24 (ISCED 5). Being in education constitutes the forth category. Education, even though in principle time-varying, enters as a time-constant covariate, which should not be problematic as very few people complete their education after the birth of their second child (Hoem et al. 2001, p. 252).

I differentiate between respondents who have 0, 1, 2 or 3 and more siblings.

Union status comprises the following states: no union, cohabitation, first order marriage, higher order marriage.

References

Adsera, A. (2005). Vanishing children: From high unemployment to low fertility in developed countries. American Economic Review, 95(2), 189–193.

Adsera, A. (2006a). Marital fertility and religion in Spain, 1985 and 1999. Population Studies, 60(2), 205–221.

Adsera, A. (2006b). Religion and changes in family-size norms in developed countries. Review of Religious Research, 47(3), 271–286.

Adsera, A. (2007). Reply to the note by Neuman ‘Is fertility indeed related to religiosity?’. Population Studies, 61(2), 225–230.

Allison, P. (1984). Event history analysis. Beverly Hills: Sage.

Axinn, W., & Thornton, A. (1993). Mothers, children, and cohabitation: The intergenerational effects of attitudes and behaviour. American Sociological Review, 58(2), 233–246.

Barber, J., Axinn, W., & Thornton, A. (2002). The influence of attitudes on family formation processes. In R. Lesthaeghe (Ed.), Meaning and choice: Value orientations and life course decisions (pp. 45–95). The Hague: NIDI-CBGS Publications.

Becker, J., & de Hart, J. (2006). Godsdienstige veranderingen in Nederland. Verschuivingen in de binding met de kerken en de christelijke traditie. Den Haag: Sociaal en Cultureel Planbureau.

Beets, G. (1993). Demographic trends: The case of the Netherlands. In N. Van Nimwegen, J.-C. Chesnais, & P. Dykstra (Eds.), Coping with sustained low fertility in France and the Netherlands (pp. 13–42). Amsterdam/Lisse: Swets & Zeitlinger.

Berger, P. (1969). The sacred canopy. Elements of a sociological theory of religion. New York: Anchor Books.

Berinde, D. (1999). Pathways to a third child in Sweden. European Journal of Population, 15(4), 349–378.

Brose, N. (2006). Gegen den Strom der Zeit? Vom Einfluss der religiösen Zugehörigkeit und Religiosität auf die Geburt von Kindern und die Wahrnehmung des Kindernutzens. Zeitschrift für Bevölkerungswissenschaft, 31(2), 257–282.

Bryant, Ch. (1981). Depillarisation in the Netherlands. The British Journal of Sociology, 32(1), 56–74.

Bühler, Ch., & Philipov, D. (2005). Social capital related to fertility: Theoretical foundation and empirical evidence for Bulgaria. Vienna Yearbook of Population Research, 2005, 53–82.

Buissink, J. (1971). Regional differences in marital fertility in the Netherlands in the second half of the nineteenth century. Population Studies, 25(3), 353–374.

Callens, M., & Croux, Ch. (2005). The impact of education on third births. A multilevel discrete-time hazard analysis. Journal of Applied Statistics, 32(10), 1035–1050.

CBS (2007). CBS StatLine, Internet database of the Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek. Voorburg/Heerlen. Accessed May and June, 2007 from http://statline.cbs.nl.

CBS (2009). CBS StatLine, Internet database of the Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek, Voorburg/Heerlen. Accessed February, 2009 from http://statline.cbs.nl.

Chatters, L., & Taylor, R. (2005). Religion and families. In V. Bengtson, A. Acock, K. Allen, P. Dilworth-Anderson, & D. Klein (Eds.), Sourcebook of family theory and research (pp. 517–541). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Chatters, L., Taylor, R., Lincoln, K., & Schroepfer, T. (2002). Patterns of informal support from family and church members among African Americans. Journal of Black Studies, 33(1), 66–85.

Corman, D. (2000). Family policies, working life and the third child in two low-fertility populations: A comparative study of contemporary France and Sweden. Paper presented at the FFS Flagship Conference “Partnership and fertility—a revolution?”, Brussels/Belgium, 29–31 May.

Crockett, A., & Voas, D. (2006). Generations of decline: Religious change in 20th-century Britain. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 45(4), 567–584.

Dekker, P., & Ester, P. (1996). Depillarization, deconfessionalization, and de-ideologization: Empirical trends in Dutch society, 1958–1992. Review of Religious Research, 37(4), 325–341.

Diener, E., Suh, E., Lucas, R., & Smith, H. (1999). Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin, 125(2), 276–302.

Dykstra, P., Kalmijn, M., Knijn, T., Komter, A., Liefbroer, A., & Mulder, C. (2005). Codebook of the Netherlands Kinship Panel Study, a multi-actor, multi-method panel study on solidarity in family relationships, Wave 1. NKPS Working Paper No. 4. The Hague: Netherlands Interdisciplinary Demographic Institute.

Ellison, Ch., & George, L. (1994). Religious involvement, social ties, and social support in a Southeastern community. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 33(1), 46–61.

Engelen, T., & Hillebrand, H. (1986). Fertility and nuptiality in the Netherlands, 1850–1960. Population Studies, 40(3), 487–503.

EUROSTAT (2006). Population statistics. Detailed tables. Luxembourg.

EUROSTAT (2007). New Cronos database (accessed in May and June 2007).

Fawcett, J. (1983). Perceptions of the value of children: Satisfaction and costs. In R. Bulatao & R. Lee (Eds.), Determinants of fertility in developing countries: A summary of knowledge, Vol. 1 (pp. 429–458). New York: Academic Press.

Festy, P. (1979). La fécondité des pays occidentaux de 1870 à 1970. Travaux et Documents No. 85 Paris: INED–PUF.

Fliegenschnee, K. (2006). There are simply always many good reasons against having a child! Fears and worries about motherhood among childless, highly educated Austrian women. Paper presented at the 33rd congress of the German Sociological Association, Kassel/Germany, 9–13 October.

Frejka, T., & Westoff, Ch. (2008). Religion, religiousness and fertility in the US and in Europe. European Journal of Population, 24, 5–31.

Glass, J., Bengtson, V., & Dunham, C. C. (1986). Attitude similarity in three-generation families: Socialization, status inheritance, or reciprocal influence? American Sociological Review, 51(5), 685–698.

Grusec, J., Goodnow, J., & Kuczynski, L. (2000). New directions in analyses of parenting contributions to children’s acquisition of values. Child Development, 71(1), 205–211.

Hadaway, K., Marler, P., & Chaves, M. (1993). What the polls don’t show: A closer look at U.S. church attendance. American Sociological Review, 58(6), 741–752.

Heckman, J., & Walker, J. (1990). The third birth in Sweden. Journal of Population Economics, 3, 235–275.

Heineck, G. (2006). The relationship between religion and fertility: Evidence for Austria. PER Working Paper 06-01.

Hoem, J., & Hoem, B. (1989). The impact of women’s employment on second and third births in modern Sweden. Population Studies, 43, 47–67.

Hoem, J., Prskawetz, A., & Neyer, G. (2001). Autonomy or conservative adjustment? The effect of public policies and educational attainment on third births in Austria, 1975–96. Population Studies, 55, 249–261.

Janssen, S., & Hauser, R. (1981). Religion, socialization, and fertility. Demography, 18(4), 511–528.

Kalmijn, M., Liefbroer, A., van Poppel, F., & van Solinge, H. (2006). The family factor in Jewish-Gentile intermarriage: A sibling analysis of the Netherlands. Social Forces, 84(3), 1347–1358.

KASKI (2007). Katholiek Sociaal-Kerkelijk Instituut, data obtained on request.

Kelley, J., & de Graaf, N. D. (1997). National context, parental socialization, and religious belief: Results from 15 nations. American Sociological Review, 62, 639–659.

Kohler, H.-P., Billari, F., & Ortega, J. A. (2002). The emergence of lowest-low fertility in Europe during the 1990s. Population and Development Review, 28(4), 641–680.

Krause, N., Ellison, Ch., Shaw, B., Marcum, J., & Boardman, J. (2001). Church based social support and religious coping. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 40(4), 637–656.

Kravdal, Ø. (2001). The high fertility of college educated women in Norway: An artefact of the separate modelling of each parity transition. Demographic Research, 5(6), 187–216.

Kreyenfeld, M. (2002). Time-squeeze, partner effect of self-selection? An investigation into the positive effect of women’s education on second birth risks in West Germany. Demographic Research, 7(2), 15–48.

Lechner, F. (1996). Secularization in the Netherlands? Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 35(3), 252–264.

Lehrer, E. (1996a). Religion as a determinant of marital fertility. Journal of Population Economics, 9, 173–196.

Lehrer, E. (1996b). The role of husband’s religion on the economic and demographic behavior of families. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 35(2), 145–155.

Lehrer, E. (2004). The role of religion in union formation: An economic perspective. Population Research and Policy Review, 23, 161–185.

Lesthaeghe, R. (1995). The second demographic transition in Western countries: An interpretation. In K. O. Mason & A.-M. Jensen (Eds.), Gender and family change in industrialized countries (pp. 17–62). Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Lesthaeghe, R., & Surkyn, J. (1988). Cultural dynamics and economic theories of fertility change. Population and Development Review, 14(1), 1–45.

Lillard, L., & Panis, C. (2003). aML Multilevel multiprocess statistical software, version 2.0. Los Angeles, CA: EconWare.

Marler, P. L., & Hadaway, K. (1999). Testing the attendance gap in a conservative church. Sociology of Religion, 60(2), 175–186.

McQuillan, K. (2004). When does religion influence fertility? Population and Development Review, 30(1), 25–56.

Mills, M., & Blossfeld, H.-P. (2005). Globalization, uncertainty and early life course. A theoretical framework. In H.-P. Blossfeld, E. Klijzing, M. Mills, & K. Kurz (Eds.), Globalization, uncertainty and youth in society. London and New York: Routledge.

Moen, P., Erickson, M. A., & Dempster-McClain, D. (1997). Their mother’s daughters? The intergenerational transmission of gender attitudes in a world of changing roles. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 59, 281–293.

Murphy, M. (1992). The progression to the third birth in Sweden. In J. Trussel, R. Hankinson, & J. Tilton (Eds.), Demographic applications of event history analysis (pp. 141–156). Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Need, A., & de Graaf, N. D. (1996). “Losing my religion”: A dynamic analysis of leaving the church in the Netherlands. European Sociological Review, 12(1), 87–99.

Neuman, S. (2007). Is fertility indeed related to religiosity? A note on: ‘Marital fertility and religion in Spain, 1985 and 1999’, Population Studies 60(2): 205–221 by Alicia Adsera. Population Studies, 61(2), 219–224.

Ní Bhrolcháin, M. (1993). Recent fertility differentials in Britain. In M. Ní Bhrolcháin (Ed.), New perspectives on fertility in Britain. Studies on medical and population subjects (pp. 95–109). London: HMSO.

Pargament, K., Koenig, H., & Perez, L. (2000). The many methods of religious coping: Development and initial validation of the RCOPE. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 56(4), 519–543.

Philipov, D., & Berghammer, C. (2007). Religion and fertility ideals, intentions and behaviour: A comparative study of European countries. Vienna Yearbook of Population Research, 2007, 271–305.

Philipov, D., Spéder, Z., & Billari, F. (2006). Soon, later or ever? The impact of anomie and social capital on fertility intentions in Bulgaria (2002) and Hungary (2001). Population Studies, 60(3), 289–308.

Pikálková, S. (2003). A third child in the family: Plans and reality among women with various levels of education. Czech Sociological Review, 39(6), 865–884.

Prskawetz, A., & Zagaglia, B. (2005). Second births in Austria. Vienna Yearbook of Population Research, 2005, 143–170.

Régnier-Loilier, A., & Prioux, F. (2008). La pratique religieuse influence-t-elle les comportements familiaux? Population et sociétés, 447.

Schoen, R., Kim, Y., Nathanson, C., Fields, J., & Astone, N. M. (1997). Why do Americans want children? Population and Development Review, 23(2), 333–358.

Somers, A., & van Poppel, F. (2003). Catholic priests and the fertility transition among Dutch Catholics, 1935–1970. Annales de démographie historique, 2, 57–88.

Statistics Netherlands. (2007). Statistical Yearbook of the Netherlands 2007. Voorburg/Heerlen.

Taylor, R. J., & Chatters, L. (1988). Church members as a source of informal social support. Review of Religious Research, 30(2), 193–203.

Te Grotenhuis, M., & Scheepers, P. (2001). Churches in Dutch: Causes of religious disaffiliation in the Netherlands, 1937–1995. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 40(4), 591–606.

Tilley, J. (2003). Secularization and aging in Britain: Does family formation cause greater religiosity? Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 42(2), 269–278.

Van Heek, F. (1956). Roman-Catholicism and fertility in the Netherlands: Demographic aspects of minority-status. Population Studies, 10(2), 125–138.

Van Poppel, F. (1985). Late fertility decline in the Netherlands: The influence of religious denomination, socio-economic group and region. European Journal of Population, 1(4), 347–373.

Ventura, J., & Boss, P. (1983). The family coping inventory applied to parents with new babies. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 45(4), 867–875.

Voas, D., & Crockett, A. (2005). Religion in Britain: Neither believing nor belonging. Sociology, 39(1), 11–28.

Wright, R., Ermisch, J., Hinde, A., & Joshi, H. (1987). The third birth in Great Britain. Nordisk statistisk sekretariat. Tekniske rapporter 46.

Yavuz, S. (2006). Completing the fertility transition: Third birth developments by language groups in Turkey. Demographic Research, 15(15), 435–460.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Michaela Kreyenfeld, Hill Kulu, Dimiter Philipov, Tomáš Sobotka, Arland Thornton and two anonymous reviewers for valuable comments on earlier drafts of the article. I am also grateful to Sylvia Trnka for language editing. The Netherlands Kinship Panel Study is funded by grant 480-10-009 from the Major Investments Fund of the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO) and by the Netherlands Interdisciplinary Demographic Institute (NIDI), Utrecht University, the University of Amsterdam and Tilburg University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Berghammer, C. Religious Socialisation and Fertility: Transition to Third Birth in The Netherlands. Eur J Population 25, 297–324 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-009-9185-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-009-9185-y