Abstract

Through the exponential growth in digital devices and computational capabilities, big data technologies are putting pressure upon the boundaries of what can or cannot be considered acceptable from an ethical perspective. Much of the literature on ethical issues related to big data and big data technologies focuses on separate values such as privacy, human dignity, justice or autonomy. More holistic approaches, allowing a more comprehensive view and better balancing of values, usually focus on either a design-based approach, in which it is tried to implement values into the design of new technologies, or an application-based approach, in which it is tried to address the ways in which new technologies are used. Some integrated approaches do exist, but typically are more general in nature. This offers a broad scope of application, but may not always be tailored to the specific nature of big data related ethical issues. In this paper we distil a comprehensive set of ethical values from existing design-based and application-based ethical approaches for new technologies and further focus these values to the context of emerging big data technologies. A total of four value lists (from techno-moral values, value-sensitive design, anticipatory emerging technology ethics and biomedical ethics) were selected for this. The integrated list consists of a total of ten values: human welfare, autonomy, non-maleficence, justice, accountability, trustworthiness, privacy, dignity, solidarity and environmental welfare. Together, this set of values provides a comprehensive and in-depth overview of the values that are to be taken into account for emerging big data technologies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Big data (Kerr and Earle 2013) is often considered to be the new gold or the new oil (Lohr 2012). Some authors have compared the implications of big data with those of the industrial revolution (Richards and King 2014). In Germany, the term Industrie 4.0 is used in order to indicate that this is a fourth industrial revolution, after those triggered by the steam engine, electricity and computers respectively (Jasperneite 2012). The enormous quantities of data that are collected, stored and processed may considerably improve the speed, effectiveness and quality of decision-making and innovation for companies, governments and researchers. The potential of big data and big data technologies is proving adept in the discovery of novel trends, patterns and relationships. As noted by the OECD (2014), the social and economic value of data is mainly reaped when data are transformed into information and knowledge (gaining insights) and then used for decision making (taking action): this is enabled by the ubiquitous “datafication” (Cukier and Mayer-Schönberger 2013) of the physical world and by the new pervasive power of data analytics.

There is no well-established definition of big data, but obviously its most prominent characteristic is its sheer volume. Apart from that, other characteristics are relevant, such as its high velocity (often real-time or nearly real-time) and its unstructured nature (including text, numbers, images, videos and sound). These characteristics of big data pose significant challenges to analytics. Typically, big data does not allow the human eye or human intuition to overview the data and the patterns and relationships hidden in it. Such hidden knowledge can usually only be discovered using advanced methods for data analysis. These new information technologies are termed as big data technologies. Some of these big data technologies focus on the storage of big data or the data management, but perhaps the most important category of big data technologies is that of big data analytics, which includes technologies such as data mining and machine learning (Calders and Custers 2013).

As with all new technologies, the question arises how to implement big data technologies in a manner that adheres to moral values that are considered to be at the heart of our Western societies. Through the exponential growth in digital devices and their computational capabilities, big data and big data technologies are putting increasing pressure upon the boundaries of what can or cannot be considered acceptable from an ethical perspective. By putting pressure upon such important ethical values as autonomy, non-discrimination, fairness, justice, privacy or human dignity they increasingly generate ethical issues that are specific to a variety of big data contexts.

Although literature specifically focussing on ethical issues related to big data and big data technologies is steadily expanding (Barocas and Nissenbaum 2014; Boyd and Crawford 2011; Engin and Ruppert 2015; Hasselbalch and Tranberg 2016; Strandburg 2014; Zook et al. 2017), much of this research focuses on separate, individual values such as privacy (Schermer et al. 2014), human dignity, justice (Sax 2016), autonomy (Pagallo 2012) or equality/non-discrimination (Barocas and Selbst 2016). Although this research is very valuable, for example, to flesh out specific values, it generally does not take a holistic approach. This can be a miss, particularly when values are competing. For instance, when focusing on a value like equality or non-discrimination, it may be very helpful to use highly sensitive personal data in big data predictive modelling (Zliobaite and Custers 2016). At the same time, the use of such highly sensitive personal data may interfere with values like privacy and autonomy (in terms of informational self-determination). Hence, a more holistic approach, taking into account sets of values (rather than individual values) is highly preferable, as it allows a more comprehensive view and further balancing of values.

In existing literature on such holistic approaches on ethics and information technology, there are basically two approaches to deal with sets of ethical issues regarding new technologies. The first approach is a design-based approach, in which it is tried to implement values into the design of new technologies. The second approach is an application-based approach, in which it is tried to address the ways in which new technologies are used. The first approach could be considered an a priori approach, whereas the second approach could be considered an a posteriori approach. However, there does not exist an integrated approach.

The lack of an integrated approach of design-based and application based approaches is a miss, as none of the two approaches covers the circular life-cycle of big data technologies. The neat theoretical distinction between different stages of technological innovation does not always exist in practice, especially not in the development of big data technologies (Fuglslang 2001). What is supposed to be a phased development process, from the flexible phase of invention or design to the more closed phase of adoption and use, in practice often is an iterative approach or circular life-cycleFootnote 1 in which new technologies and new applications of existing technologies are built on each other. In such processes, the different stages are sometimes overlapping, sometimes non-sequential and sometimes running in parallel. Also, big data based products and services are never really finished, but rather are continuously updated and revised. This is problematic for the abovementioned ethical approaches, as it may be hard to choose the most appropriate ethical approach.

A consequence of this integrated, holistic approach is that also a more heterogenic network of actors are involved in upholding these values (Akrich 1992; Bijker 1995; Bijker and Law 1992; Latour 1987). Not just the engineers or designers of the big data technologies and applications, but also policy makers, citizens and users have a joint responsibility in cultivating ethical values (Vedder and Custers 2009).

Another miss in the existing literature is that none of the ethical approaches is specifically focused on big data and big data technologies. The approaches suggested typically are somewhat general in nature, which offers a broad scope of applying them, but this may not always be tailored to the specific nature of big data related ethical issues. In the context of big data, there may exist not only ethical issues on how to interpret and safeguard values and on how to balance competing or conflicting values, also issues in which it may be unclear which values are at stake and issues in which some values may not have been identified yet.

The goal of this paper is to integrate existing design-based and application-based ethical approaches for new technologies and further focus this integrated result to the context of big data technologies. This will provide a comprehensive and in-depth overview and list of values that are to be taken into account for emerging big data technologies. The use of this overview and value list can also be beneficial for rolling out social impact assessments (Wright 2012; Wright and De Hert 2012) with respect to big data technologies in a diversity of contexts.

The findings in this paper are based on the preliminary results of a project funded by the European Commission (Custers et al. 2017). This project, called e-SIDES has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No. 731873. This paper is divided into five sections. In Section two we describe and further explain the methodology/approach taken in this paper. In Section three we introduce two lists from the domain of responsible research and innovation, one from applied virtue theory, and one list deriving from the area-specific discourse on biomedical ethics. In Section four we distil from these lists an overview of values that are both useful for implementation in the design and the practical use of big data technologies. In Section five we provide recommendations regarding how our integrated list of values could be beneficial in assessing the broader ethical implications of big data technologies.

Approach

In order to integrate existing design-based and application-based ethical approaches for new technologies and further focus the resulting list of values to the context of emerging big data technologies, we used a two-step approach. First, we explain how we collected and selected existing approaches. Second, we explain how we distilled from the selected approaches a comprehensive overview of relevant values in the context of emerging big data technologies.

Collection and selection

Our starting point was to look for any literature containing lists of values, from different ethical perspectives, regardless of the context for which they are intended or in which they are used. Hence, also lists of values for non-technological contexts were considered. Only literature that included a list of values, indicating a more holistic approach, was included; literature on a single value was not considered. Our search included literature on historical lists in virtue ethics, lists in healthcare and other societal sectors (such as education, food and life sciences, journalism, business ethics, etc.), literature on design-based considerations for engineering, literature on application-based and procedural considerations for new technologies, literature on values for emerging or novel technologies and literature on novel branches of virtue ethics. Our desk research yielded a broad collection of in total 21 value lists with sets of values from different ethical perspectives. An overview of this longlist can be found in Appendix A.

Out of these 21 lists, the first two lists emerged as historical lists in virtue ethics. Consequently, the first value list we considered is of Aristotle’s virtues (Aristotle 1947) and the second of St. Thomas of Aquinas (McInerny 1997). We also assessed value lists or ethical codes of more recent times and were most prominent for certain societal contexts or disciplines. (They contained prominent ethical codes for certain professions only). Here we distinguished lists that were meant for healthcare oriented professions, that appear to be more abundant and elaborated, and lists that were meant for professions beyond healthcare. We assessed five lists that were prominent in healthcare. These are the value list of bioethics by Beauchamp and Childress (2012a, b), the Declaration of Helsinki, containing ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects (World Medical Association 2010), a list called nine ethical values of master therapists (Jennings et al. 2005), a list containing principles for health technology assessment (Turchetti et al. 2010), and the ethical matrix of Mepham (2010), which is a list from the context of food ethics in relation to healthcare.

Beyond the discipline of healthcare we assessed the five further values lists that are prominent in particular disciplines or professions. This category of lists contains a list on professional codes of ethics of the (US) National Society of Professional Engineers (NSPE Ethics Reference Guide for Engineers 2017) a list of the values and ethics codes of social workers (Parrott 2014), a list including a code of ethics of professional journalists (Society of Professional Journalists 2014), a list of business ethics principles for executives (Josephson Institute of Ethics 2010), and a list of the School of Educators which contains ethical principles for teachers (2012).

With respect to value lists focusing on the design phase of technologies, we identified list of value-sensitive design (Friedman et al. 2006). Searching for application-based approaches yielded two lists, i.e., Google’s AI principles aimed at ethical principles for daily use and the datasheets for datasets approach (Gebru et al. 2018). Focusing on lists relevant for novel and emerging technologies, we identified three value lists: the anticipatory emerging technology ethics list of Philip Brey (2012), an ethical delphi for assessing ethical issues emerging in relation to novel biotechnologies (Millar et al. 2007), and the technomoral value list of Shannon Vallor (2016). When examining novel branches of virtue ethics, we identified three further lists: a list on feminist ethics (Jagger 1991), a list on insurrectionist ethics (McBride 2017), and a list on marxist ethics (Beckledge 2008). The next step was to select which lists are most appropriate to use for further integration and contextualization for emerging big data technologies. It may be obvious that many of the ancient lists are more complicated to apply to these new technologies, but nevertheless they are very valuable as they represent rather general values. When lists are in the same line of thought, we chose the list that is most developed towards big data technologies. For instance, the lists of Aristotle and of St. Thomas of Aquinas were not selected, because Shannon Vallor’s list of technomoral virtues (see below) relies on both these lists. Therefore, we use her list of values rather than the ones she builds on.

Another selection criterion for narrowing down the number of collected lists was that lists of values should not be at an aggregated level. For instance, Mepham’s ethical matrix, although it has prominent influence in biomedical ethics, was not included in our analysis because Mepham uses aggregated values in his matrix. He clusters individual values in three groups, welfare, dignity and justice. These values are already represented in several other lists.

At the other end of the spectrum, lists of values that are too context specific were not included. This applies to most of the professional codes of ethicsFootnote 2 that were identified. These are often based on other lists, such as that of Aristotle, and they are often strongly context specific, making it hard to apply them for emerging big data technologies. It should be noted that no list of values was found that actually had big data or big data technologies as its specific context.

This process of collection and selection resulted in four highly relevant lists of values. These high quality lists are widely acknowledged in applied ethics and constitute indispensable bases for the integration approach in this paper. The first value list is a technomoral value list introduced by Shannon Vallor (2016), the second is the value list for anticipatory emerging technologies introduced by Philip Brey (2012), the third a value list is the list for values-sensitive design (VSD) introduced by Batya Friedman et al. (2006) and the fourth is a value list for biomedical ethics introduced by Tom Beauchamp and James Childress (2012a, b). The biomedical ethics list may seem a bit strange in this context, as the technologies and practices are somewhat disanalogous to big data at first sight, but it is included because bioethics is among the first and most developed branches of applied ethics. Furthermore, the field of bioethics was developed in reaction to rapid developments in technology and medicine in the twentieth century, a situation that bears some resemblance to the current rapid developments in big data technology. Both situations try to deal with ‘technological turbulence’ and with situations in which the technology allows for many options, but in which at the same time a clear normative framework for assessing those options is lacking. These four lists together cover both the design-based approach and the application-based approach discussed above. The lists of both Friedman et al. and Brey focus on the design-stage. These lists can be applied to big data technologies but are not specifically tailored to these technologies. The list of Beauchamp and Childress focuses on the application-stage, but does not specifically take into account big data technologies. The list of Vallor does include both design and application stage, but is not tailored to big data technologies. The background and contents of the four selected lists will be discussed in the next section.

Integration

The next step was distilling from these four lists a single list of values that can be used in the context of emerging big data technologies. The goal was to come to a comprehensive list, in line with the more holistic approach that we think is needed. However, looking at the values on the selected lists of values, it is obvious that some of these values may have a very different meaning, even though some of them have the same names. Sometimes, a values is already significantly disputed with the context of one list. For instance, a value like justice can have very different interpretations, ranging from justice as fairness, justice as desert or justice as equality. Moreover, some lists have different labels for similar values. For instance, one list mentions honesty, which another list labels veracity. Furthermore, since the lists are all different, it is obvious that some lists lack particular values mentioned on other lists. For instance, privacy is mentioned on two lists, but absent on two other lists. All this makes it hard to really align the four lists. However, it is important to keep in mind that the goal is not to force a fit or tweak all lists into one singular list, but rather to distil or extract a comprehensive list of values from these lists.

Therefore, we do not describe in-depth the exact meaning of each value on each list in that specific context (an exegesis we consider beyond the scope of this paper), but take a more abstract approach. Hence, instead of arguing that a value like justice means x in the context of one list and y in the context of another list and trying to align those meanings, we reason as follows: acknowledging its different interpretations in different contexts, we see justice as a value appearing on all lists, so it must be a key value. For that reason only, we put it on our comprehensive list and then consider how justice should be regarded in the context of big data technologies. The latter part, applying particular values in the context of big data technologies, can obviously be inspired by the different meanings of the values on the four lists.

When trying to distil a comprehensive set of values from the four lists of values from different ethical perspectives, important methodological issues in our approach are to ensure completeness and avoid overlap. Should a value be considered as relevant only when it appears on all lists or already when it appears on only one list? Or something in between? An obvious approach would be to add all lists of values to each other, but that would create a long list with many overlaps. At the other end of the spectrum of integration methods would be to only include those values present on all lists of values, but that would create a list of values that may not be comprehensive with respect to emerging big data technologies.

Starting with the first consideration (i.e., overlapping values in one integrated list), ideally, we would like to create a list of values that do not overlap. However, also in this case it is important to note that a list of non-overlapping issues is not realistic. Such a non-overlapping categorization does not exist in any of the ethical perspectives under consideration in this paper. Hence, even though the values identified are distinctly different, they may overlap to some extent. An example of this is automated decision-making on the basis of big data analytics by profiling. In such processes the autonomy of data subjects may be infringed as such decisions often constrain choices of the profiled individual. At the same time also transparency about these processes may be lacking which in itself constrains choices and consequently can contribute to limit autonomy. Although autonomy and transparency are distinctly different issues, in their effects they can overlap.

Regarding the second consideration (i.e., completeness or exhaustiveness of the integrated list), we obviously want to create a list of values that is as complete as possible. However, although a complete, exhaustive list of values is the ideal goal, it is important to note that it is impossible to provide such a complete, exhaustive list. On the one hand, because no theoretical framework exists that is a closed system in which it is possible to take an exhaustive approach. On the other hand, even if a closed system were available, it would be impossible to take an exhaustive approach because the big data technologies and applications are rapidly changing all the time (Vallor 2016). Nevertheless, we think the comprehensive approach for and integrated list of values in big data contexts in this paper makes it very likely that the most important issues in each of the disciplines investigated are actually identified.

To avoid both pitfalls, navigating between Scylla and Charybdis, we took a more tailor-made approach in which we assessed each value separately. For this assessment, we refer to Section four of this paper.

Furthermore, we used two methods to validate our results in practice. First, the values resulting from the literature review were supplemented with expert knowledge from the researchers in the project and external experts. The expert knowledge was used to assess the completeness and exhaustiveness of the collected results (see “Collection and selection”). Where apparent gaps appeared, expert knowledge was used to add further issues to the lists and further qualify the values on the lists. Furthermore, expert knowledge was used to categorize the results into clear, well-defined categories that avoid overlapping (to the extent possible, see above). Experts were consulted within the professional networks of the researchers involved in the project,Footnote 3 but also at expert forums.Footnote 4

Second, two workshops were organized to obtain additional in-depth knowledge on the values identified and to identify new ones, and, to validate the preliminary results of our integration. One workshop was co-located with a major ethics conference,Footnote 5 the other workshop was co-located with a major big data conference.Footnote 6 The workshop format was designed to allow for the maximum participation and interaction of the attendees, with a live survey to gather and discuss opinions. In particular, the workshops focused on to what extent the participants considered these challenges relevant in the big data arena and thus to be taken into account by the community.

Note that both the expert consultations and the two workshops were used for validation only—this research could have been done with the literature review only. However, in order to further ensure our comprehensive approach, we added these elements to our methodology. The experts were presented the four selected lists of values together with our integrated list of values, next we talked them through our goals and approaches and then asked them whether we were missing important values and discussed with them the resulting list of values and how to apply these values in the context of big data technologies. In most instances, this just confirmed that our list of values was considered comprehensive by the experts and that we were using a sound approach. The discussions with the expert were particularly valuable in deepening our understanding of and thinking on how to regard particular values in the context of big data technologies.

Values for emerging technologies

In this section we introduce four value lists that are highly valuable and esteemed in ethics, on which we base the integration approach in this paper: one from the domain of applied ethics, two from the domain of responsible research and innovation and one list from an area-specific discourse: biomedical ethics. More specifically, the first subsection addresses the technomoral value list introduced by Shannon Vallor (2016), the second subsection the value list for values-sensitive design (VSD) introduced by Batya Friedman et al. (2006) the third one the value list for anticipatory emerging technologies introduced by Philip Brey (2012), and the fourth subsection deals with the value list for biomedical ethics introduced by Tom Beauchamp and James Childress (2012a, b). From the perspective of our integrated approach for big data technologies all four lists are of vital, yet at the same time also partial, relevance. Each list encapsulates differing characteristics regarding the extent to which we consider it vital for our integrated approach. However, the partiality of these lists is also a reason in itself for their integration.

List of ‘technomoral values’

Shannon Vallor’s technomoral values are from the perspective of our integrated approach for big data technologies vital, because she is a pioneer in her approach in investigating current intricacies at the cross-roads of emerging technologies and virtue ethics and she applies moral virtues that have existed for centuries to emerging technologies. She bases her analysis on ancient Greek philosophers like Aristotle (1947), medieval Christian philosophers like St Thomas of Aquinas (1997) and also Eastern philosophies like Confucianism (Confucius 1997). However, she argues these century-old virtues need explicit adaptation to our current technology-mediated times. Moreover, she underlines the acute need for exploring what ethical values and norms are about to erode in our digitalized society: “we need to cultivate in ourselves, collectively, a special kind of moral character, one that expresses what I will call the technomoral virtues.” (2016, p. 1) Furthermore, she focuses both on the design and the application phase of emerging technologies. Throughout her philosophical and socio-technical exploration of ethical challenges she defines the following ten values as most worthy of upholding: honesty, self-control, humility, justice, courage, empathy, care, civility, flexibility, perspective, magnanimity and technomoral wisdomFootnote 7 (see Table 1).

Yet, regarding our integrated approach, her list only provides a partial fit. Notably, throughout her technomoral values list, her selection of values does not account for the circular life-cycle of big data technologies where phases of design and application often overlap, run parallel or flow from each other. Second, although she stresses the importance of the collective cultivation of values, she does not use a holistic approach regarding the network of stakeholders involved in big data relations (such as engineers, developers, designers, data scientists, users, data subjects, citizens, policy makers and legislators). This seems to be a miss, as the successful cultivation of ethical values hinges upon the extent to which these values are shared, respected and enacted mutually throughout relationships in big data-mediated networks. One stakeholder alone cannot uphold a value, but such upholding also requires mutual efforts from other stakeholders involved.

List of values from value-sensitive design

The value-sensitive design (VSD) list of Friedman et al. is from different perspectives vital and from different perspectives partial in relevance regarding our integrated approach for big data technologies. Extensive research demonstrates that the need for value-sensitivity in design is indispensable (Manders-Huits and Van den Hoven 2009; Van den Hoven 2013), therefore using a prominent value list of VSD for the integration of our value list for big data contexts is vital. The value-sensitive design value list is vital more specifically, first because it clearly defines criteria for value-conscious innovation, including new information and communication technologies. Second, the value list of VSD does not position designers as neutral agents who only fulfil the production of technologies, but as agents who shall be held accountable for the effects of their inventions on the broader public (Friedman et al. 2006).Therefore, designers should account for moral values already during the designing process of technologies. Friedman, Kahn and Borning in their work define a set of human values with ethical import, which they suggest not as a comprehensive list, but as a set of values that can guide developments of value-sensitive technologies for human use. A third important reason why their list is vital for our integration is, that in their selection of values Friedman et al. rely on an extensive list of scholarly literature that advocates for the implementation and active use of one or more of these values. Their list comprises the following VSD values (Ibid.; 17–18): human welfare, ownership and property, privacy, freedom from bias, universal usability, trust, autonomy, informed consent, accountability, courtesy, identity, calmness, and environmental sustainability (see Table 1). According to Friedman et al. the first nine values can be considered as requirements to embrace in general technology design environments, whereas courtesy, identity, calmness and environmental sustainability are value-requirements for specific kinds of technology design. However, the value-sensitive design value list from the perspective of our integrated approach is also partial. One reason for that is that VSD only focuses on the design phase and not on the application phase. Yet, as we will demonstrate in section four of this paper, a large set of these values is also highly useful to uphold both during design and application, and generally throughout the circular life-cycle of big data technologies. A second reason for partiality relates to the first, and reflects that the values for VSD do not account for the circular life-cycle of big data technologies, where phases of design and application often overlap or even co-create each other. A third reason for partiality is that VSD does not take a holistic approach either. VSD does not regard the network of stakeholders involved in big data relations as sharing responsibility in cultivating values. Although the take of designers is crucial in upholding values, the successful cultivation of these values hinges upon the shared commitment of other stakeholders.

List of values from ‘anticipatory emerging technology ethics’

The value list of anticipatory emerging technology ethics, which is developed by Philip Brey (2012) is in another way different regarding why it is vital and partial in relevance as to our integrated approach for big data technologies. The value list of anticipatory technology ethics is vital, first of all because Brey developed the anticipatory technology ethics theory in relation to a diversity of other technology ethics literature, such as ethical technology assessment, techno-ethical scenarios and the so-called ETICA approach. By bringing such a broad diversity of individual domains in technology ethics together, Brey provides a highly comprehensive and in-depth comparative ethical analysis and argumentation for his anticipatory emerging technology ethics theory. Second, differing from the earlier two lists, values are specified for design and application stages within anticipatory technology ethics and are therefore valuable for our integrated approach. Moreover, Brey introduces three stages of technology development: the level of the technology, the artefact, and the application. He distinguishes these levels from the perspective of how values can be integrated. Third, the value list of anticipatory emerging technology ethics is vital for our approach, because Brey offers for each of these stages a reference list of values to uphold from an ethical perspective. The values listed in anticipatory emerging technology ethics are the followingFootnote 8: harms and risks, rights and freedoms, autonomy, human dignity, privacy, property, animal rights and animal welfare, (distributive) justice, and well-being and the common good (see Table 1).

Reasons why the anticipatory emerging technology ethics list from the perspective of our purposes in this paper remains partial are the following. First, Brey defines ‘technology’ as something that results from any artifact or application; ‘artefact’ (including functional systems and procedures) being the things that are on the basis of a technology developed; ‘applications’ being the particular ways of using an artifact or procedure, or particular ways of configuring it[application] for use. Although these stages can make perfect sense for certain contexts, given the circular life-cycle and the multiplicity of contexts of big data technologies, the stages distinguished by Brey would provide a partial fit for our integrated approach for big data technologies. Notably, within big data contexts it is often difficult to distinguish, for instance, whether an application results from a technology or a technology results from an application. A second reason for partial relevance, which follows from the first, is that values are specified separately, and it is not specified which values apply simultaneously to both stages, as is the case in the context of big data. Third, anticipatory ethics does not take a holistic approach and does not include a broad set of stakeholders in big data. Consequently, the value list does not pay attention to the shared responsibility of stakeholders regarding the implications of technological use and in upholding values.

List of values from biomedical ethics

The value list from biomedical ethics provides in another set of different reasons why this list is vital, but also partial in relevance for our integrated approach regarding big data technologies.

The biomedical ethics value list had been developed by Tom Beauchamp and James Childress (Beauchamp and Childress 2012a, b) in their book Principles of Biomedical Ethics from 1979. For our integrated approach towards big data technologies their value list is vital, first because it established far-reaching influence in medical ethics and beyond (McCormick 2013; Page 2012; Waltho 2006; Westin and Nilstun 2006) mostly because of the broad usefulness of the convincing moral theory for healthcare these values are stemming from. They distinguish the following four main principles or values: autonomy, non-maleficence, beneficence and justiceFootnote 9 as the most essential guidelines to consider within patient and medical professional relations (see Table 1). This list had been extended by Snyder and Gautier (2008) by two other values: the principle of respect for dignity and the principle of veracity (see Table 1).Footnote 10 Yet, the four core values still provide the basis for ethical codes and trainings in medicine (Page 2012; Price et al. 1998). A second reason why this list is vital for our integrated approach is that Beauchamp and Childress explicitly frame these values as prima facie duties of healthcare professional. In other words, they argue that a continuous ‘duty of care’ should sustain these principles during any action in healthcare. This puts an active commitment for ethical handling on the shoulders of professionals and such activation for ethical actions would also be vital for big data contexts. A third reason, why this list is vital for our approach, is that Beauchamp and Childress stress, in particular, the importance of a continuous aspiration for fairness and equality during (healthcare) handlings.

The following characteristics render this value list partial in relevance for our integrated approach regarding big data technologies. First, each of these values had been conceptualized for the phase of practice or application, but not for the design. Consequently, this list does not account for the circular life-cycle of big data technologies either (Custers 2005). Second, this is an area-specific professional ethical code list, therefore cannot provide a blanker fit for the multiplicity of contexts where big data is developed and used. Third, they do not have a holistic approach either towards a broad set of stakeholders involved in big data contexts. Consequently, they are not meant for the mutual cultivation of common ethical grounding throughout interactions of stakeholders in big data contexts.

Value considerations for techno-social change in big data contexts

Using the methodology described in “Collection and selection”, we distilled from the four lists of values detailed in the previous section a set of ten values in total for big data technologies used in multiple contexts: human welfare, autonomy, dignity, privacy, non-maleficence, justice, accountability, trustworthiness, solidarity and environmental welfare (see Table 1).

In this section we elaborate on each of these values and their meaning in emerging big data technologies. First, we depict them with reference to all four lists of values detailed in the previous section. Second, we demonstrate our arguments why each value should be considered and treated as a placeholder for ethical interactions throughout big data contexts. The latter also entails that we provide examples for issues where each of these values are put under pressure in big data contexts. Finally, notwithstanding the starting point of this article that all listed values should be upheld throughout the whole life-cycle, we will explicate for every value in which phase of the big data life-cycle we foresee extra attention will be needed to ensure an ethical foundation for big data technologies.

Note that we do not put these values in any hierarchical order, although we recognize that some of the identified values can be derived from combinations of other values and thereby overlap. Putting the values in a hierarchical order would raise many questions that are beyond the scope of this paper. We do try to highlight in the text below to what extent some values are derived from other values and how values from the different lists overlap.

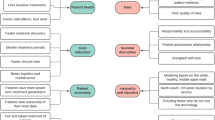

Below we discuss the integrated list of values and illustrate how they may be under pressure in contexts of big data technologies. The issues putting pressure upon each value are also highlighted in Table 2.

Human welfare

Human welfare is perhaps one of the most straightforward values to protect (Hurthouse 2006). This value did not come explicitly to the foreground on all four value lists, yet each list where human welfare is not listed contains values that are very close to human welfare.

On the list of technomoral values human welfare can rather be seen as related to the value of care. Care (loving serving to others) is defined by Vallor as the skilful, attentive, responsible and emotionally responsive disposition to personally meet the needs of those with whom we share our techno-social environment. In relation to care Vallor argues that some of the biggest dangers of emerging technologies for human welfare can appear when “emerging technologies are used as supplements for human caring” (Vallor 2016, p. 119), for instance, when a robot delivers medicine could be seen as a caring task being completed, yet the human touch that a patient would need might be missing. Value-sensitive design distinguishes it specifically. In VSD, human welfare refers to people’s physical, material, and psychological well-being. Anticipatory emerging technology ethics refers to well-being and the common good in general. Brey refers to well-being as one of the most general values on his list. In anticipatory technology ethics well-being means being supportive of happiness, health, knowledge, wisdom, virtue, friendship, trust, achievement desire-fulfillment. This also includes being supportive of vital social institutions and structures, democratic institutions and cultural diversity. In biomedical ethics the value of beneficence is described as the principle of acting with the best interest of the other in mind. Therefore, from the value list of biomedical ethics beneficence is therefore most closely related to human welfare. Beneficence can also be regarded as something that preserves human welfare. Welfare may also overlap with the value of solidarity (see below).

Regarding our criteria for an integrated approach that accounts for the circular life cycle of big data and that a broad range of stakeholders have a share in how values become upheld in big data contexts, human welfare finds a pivotal place on our value list. Human welfare should be accounted for both during the design and the application stage of big data technologies,—no matter whether these stages follow-up, run parallel or are self-generating each other holistically by all stakeholders. This value can explicitly be put under pressure in big data contexts as the example of the healthcare robot, also referred to by Vallor (Ibid.), also demonstrates this. Healthcare robots are designed to register patient’s data. Yet, in practice newer and newer data is fed into robots by multiple stakeholders, e.g. doctors, pharmacists, nurses or others, generating new data by regular updates and prognosis on a patient’s health condition. The latter could also be considered as a form of self-generated renewal in design regarding prognosis on a patient’s health by big data. Although the role of robots in supplying services for patients (and healthcare workers) should not be underestimated, this example also underlines that the network of designers, developers, users and other stakeholders, including robots themselves, mutually share responsibility in how human welfare as a value becomes upheld or put under pressure throughout the whole lifecycle of big data technologies.

Autonomy

Autonomy as a value is present on the value lists of VSD, anticipatory technology ethics and biomedical ethics, but not on the list of techno moral values. Autonomy on the VSD list refers to people’s ability to decide, plan, and act in ways that they believe will help them to achieve their goals. In anticipatory emerging technology ethics, autonomy is the ability to think one’s own thoughts and form one’s own opinions and the ability to make one’s own choices. According to anticipatory emerging technology ethics, autonomy pre-requires responsibility and accountability and in the digital era it should also include informed consent. In biomedical ethics, autonomy, as mentioned above, is the right of the individual of making his or her own decision or choice. Vallor’s technomoral value of magnanimity and courage—daring to take risks—are closely related to autonomy. Magnanimity or moral leadership, for instance, in Vallor’s view is a value that everyone needs to cultivate in him/herself. Magnanimous leaders are those who can inspire, guide, mentor and lead the rest of us at least towards the vicinity of the good. Magnanimity is therefore a quality of someone who can by example be a moral leader especially during techno-social change. Such stakeholders as technology designer, entrepreneurs, data scientists but also others involved in big data networks should dispose with this quality or ethical characteristic. The technomoral value of courage, what Vallor describes as intelligent fear and hope, is also closely related to autonomy because only a person who is autonomous could choose courageously. Yet, courage facilitates autonomy. Courage is a special facilitator of autonomy, because it is an admirable quality for making rather difficult choices than easy ones. As to emerging technologies, Vallor calls for embracing this value by cultivating a “reliable disposition toward intelligent fear and hope with respect to the moral and material dangers and opportunities presented by emerging technologies”. Certain expectations are by design inherent in big data technologies, yet unexpected implications emerge trough their use. To cultivate a reliable disposition toward intelligent fear and hope by humans and to equip stakeholders by features that facilitate such disposition are both pivotal requirements to enact a form of autonomy that is conscious about the unexpected implications of big data use.

An autonomous person in our big data era should desirably be a magnanimous and courageous one in his/her activities. Furthermore, this autonomy should be facilitated by the broader network of stakeholders connected to big technologies. In order to uphold autonomy, it is crucial to acknowledge the connection between the design stage and the application stage. A feature that is instrumental in facilitating such autonomy by a diverse set of big data stakeholders is transparency. If transparency is put under pressure in the design stage, so is autonomy in the application stage. For instance, if a big data mediated decision process is designed in such a manner that there is no way for citizens to come to understand how a decision has been reached, they cannot enact their autonomous character, for instance, to seek recourse. Furthermore, autonomy can also be in danger when big data-driven profiling practices limit free will, free choice and turn out to be rather manipulative instead of supportive in raising awareness or cultivating knowledge about, for instance, news, culture, politics and consumption. As this could be an unforeseen consequence of the application of big data technologies, it is necessary to keep a close eye on how autonomy actually takes shape in practice. Consequently, autonomy should be embraced as a value throughout the entire life-cycle of big data technologies, with extra attention to the direct connection between the design and application stage.

Dignity

Dignity (Düwell 2017) as a value cannot be found on all four lists of values, only on the list of anticipatory emerging technology ethics and biomedical ethics. Human dignity in anticipatory emerging technology ethics includes both self-respect and respect towards all humans by humans without any interest. On the list of technomoral values empathy is closest in notions to dignity. Empathy (compassionate concern for others) is explained by Vallor as a technomoral value that cultivates openness to being morally moved to a caring action and led by the emotions of the other members of our technosocial world. This could mean for cultivating compassion both for others’ joy as well as pain. Vallor calls for embracing this value, because the amount of joyful and painful events that are mediated via digital technologies is unseen, therefore we can too often be called for empathic action. Nevertheless, she argues that we need to adapt our receptors of empathy to these technological changes. This is crucial in order not to become narcissists and we consider this is also crucial to uphold someone’s dignity within big data contexts.

The value-sensitive design list does not refer to dignity but to identity. Yet, in our view these two notions are intertwined. In VSD, identity refers to people’s understanding of who they are, embracing both continuity and discontinuity over time, but dignity also requires a similar understanding so that one can respect this value. Following from this we could say that dignity and identity mutually predestine each other: when dignity is preserved so is identity, and when identity is preserved so is dignity. Human dignity can therefore be regarded as a prime principle since all implications of big data-mediated interactions affect humans and to differing degrees also their identity and dignity.

Dignity is under pressure in big data contexts. For instance, when revealing too much about a user to others, principles of data minimization and design requirements of encryption appear to be insufficient. Adverse consequences of algorithmic profiling, such as discrimination or stigmatization demonstrate that dignity is fragile in many contexts of big data, but it in particular becomes pressured in the application stage. Being confronted with discriminating profiles and opaque data-driven decisions, a citizen may experience a Kafkaesque situation in which her view and agency no longer is acknowledged. When a person no longer is treated as someone with particular interests, feelings and commitments, but merely as a bundle of data, her dignity may be compromised. The example of a black couple having been auto-tagged as gorillas (Gray 2015), also demonstrate this. For instance, by actively raising awareness about the consequences of online search results upon algorithmic decision-making processes, where search results are predicated upon the design and application of big data, could assist in effectuating respect for the value of dignity in big data contexts. By raising awareness and, if stakeholders acknowledge their responsibilities in upholding dignity, much of the diverse effects of big data-mediated interactions can be minimized.

Privacy

Big data based analytics are often highly privacy-invasive; therefore we acknowledge the importance of privacy as a value and include it also on our list of values for big data contexts. Out of the four lists of values detailed in section three only value-sensitive design lists privacy as a separate value to cherish. The value lists of biomedical ethics and technomoral values do not refer to privacy explicitly. Anticipatory emerging technology ethics in relation to privacy focuses on the fundamental right to privacy and on notions of privacy that are known from the data protection perspectives, such as informational privacy but also on its physical extensions such as the notion of bodily privacy depicts this. A third notion of privacy in anticipatory emerging technology ethics relates to the relational character of privacy. This is also a useful notion for the integrated approach in this paper, as privacy should come about through mutually respected (not only legal) agreements among stakeholders. Anticipatory emerging technology ethics underlines that privacy has a property component, therefore the value of property in a certain form is also considered useful to support privacy.

VSD refers to privacy as a claim, an entitlement, or a right of an individual to determine what information about him or herself can be communicated to others. Given the scope of privacy for big data networks, we also considered informed consent and ownership and property as related values. Informed consent refers to garnering people’s agreement, encompassing criteria of disclosure and comprehension (for “informed”) and voluntariness, competence, and agreement (for “consent”). Ownership and property refers to a right to possess an object (or information), use it, manage it, derive income from it, and bequeath it. All these rights can be regarded as substitutes of a broader definition of privacy, as for instance, personal data can be owned by others than the individual referred to by the data within big data contexts. Therefore, actively enacting the value of informed consent is another prerequisite to facilitate privacy as a value by all stakeholders in big data-mediated relationships.

Since the rise of the internet there is extensive literature on privacy (Custers and Ursic 2016; De Hert and Gutwirth 2006; Gray and Citron 2013; Hildebrandt and de Vries 2013; Koops et al. 2017; Moerel et al. 2016; Nissenbaum 2010; Omer and Polonetsky 2012). Privacy as an ethical value for big data contexts is the closest in its scope to privacy as a fundamental right (as also listed on Brey’s list). Privacy as fundamental value first includes respect for others, and specifically respect for someone’s private sphere, conversations, writing—e.g. confidentiality of mail—and also any action that one keeps intentionally unexposed to the broad public. A cornerstone of privacy as a fundamental value lies in respecting the boundaries someone else has drawn him/herself and the boundaries one would also like to be seen protected from intrusion by others.

These instances of privacy within big data-mediated interactions are under constant pressure. Persons can increasingly easily be identified in datasets even if technical measures of anonymization are in place. Simply the myriad of correlations between personal data in big data schemes allows for easy identifiability. Therefore, the growing technological possibilities offered by big data allow for many ways to disrespect one’s private interactions and relations. Therefore, privacy needs to be at the heart of the design process, by making sure it is a key design requirement and not merely something that is being “added” at the end. However, due to the mentioned possibilities of identifying or singling out someone, privacy can also become under siege in the implementation and application stage. Therefore, an integrated approach in respecting one’s privacy holistically by all stakeholders remains pivotal.

Non-maleficence

Non-maleficence is the value of not causing harm to others. Non-maleficence is only explicitly stated as a core value on the value list of biomedical ethics (Beauchamp and Childress 2012a, b). Non-maleficence, according to Beauchamp and Childress, is rooted in the Hippocratic Oath, and means ‘above all, do no harm’ to others. Regarding the technomoral values of Vallor, non-maleficence is intertwined with humility and self-control. Regarding the value sensitive design value list, calmness (or certain degree of self-control) is most closely related to non-maleficence. Considering the anticipatory emerging technology ethics list avoiding harms and risks as core principle provides the closest overlap with the value of non-maleficence.

Humility focuses on knowing what we do not know. Vallor stresses the importance of this value regarding new technologies, because practicing humility as a technomoral virtue, in her view acknowledges “the real limits of our technosocial knowledge and ability, reverence and power at the universe’s power to surprise and confound us, and the renunciation of the blind faith that new technologies inevitably lead to human mastery and control of our environments”. Practicing humility in a big data era, therefore, could serve as an ethically cautious behaviour both during design and application of big data. Calmness in VSD refers to a peaceful and composed psychological state can be regarded as a pre-requisite for remaining non-maleficent within and across big data contexts. Avoiding harms and risks is a principle and desired attitude which in Brey’s view encompasses that new technologies may contain different harms and risks consequently precaution toward these technologies is necessary. This implicit precautionary attitude renders this principle of Brey being closely related the value of non-maleficence (‘do not harmFootnote 11’).

Non-maleficence is first and foremost a central value in the design process. Actors such as developers, data scientists, and commissioning parties have to anticipate and take into account the wider societal impact of their applications. It has to be noted that, within the context of big data technologies, non-maleficence is perhaps one of the most difficult values to implement as the predictive logic in big data based algorithms can often result in unforeseeably offensive outcomes. These algorithmically mediated results of big data can therefore easily put pressure upon non-maleficence. For instance, false positive matches in law enforcement, such as the recent case of falsely flagged children as security risks on no-fly lists in Canada, demonstrate that big data-based analysis can result in unjustified accusations of innocent persons (Bronskill 2018). In order to uphold non-maleficence, it is important to be humble and acknowledge that big data technologies might have unforeseen and unwanted consequences. Therefore, non-maleficence both as a design requirement for technologies and an attitude requirement for a wide range of stakeholders, including policy makers, data scientists and users should be embraced throughout different contexts of big data.

Justice

Justice as a value can be considered as a prime requirement in everyday life. Except the list of VSD, justice appears on all three other lists. Justice on the techno moral value list is the broadest among values and based on Aristotelian and Confucian understandings Vallor explains justice as the “just treatment of others”. We can also understand this value under the broader notion of human benevolence. Vallor claims that “data-mining, pervasive digital surveillance and algorithmic profiling, robotics” currently fuel the growth in social inequalities and technomoral justice is needed to restore or remedy inequalities. In biomedical ethics justice is about upholding rightness. In anticipatory emerging technology ethics justice is understood in its broadest terms. Justice involves the just distribution of primary goods, capabilities, risks and hazards, non-discrimination and equal treatment relative to age, gender, sexual orientation, social class, race, ethnicity, religion, disability, etc. Furthermore, it also involves the geographical dimensions, as global north–south justice and age-related aspects, such as intergenerational justice.

Value-sensitive design does not list justice as a value specifically. It lists however freedom from bias and universal usability and we consider these two closely related to justice. First, regarding the freedom from bias Friedman et al. underline the essential need to prevent or remedy “systematic unfairness” as a form of bias. Within the context of big data, systematic unfairness can also be regarded as a form of pressure upon the value of justice. Systematic unfairness occurs, for instance, in the stage of analysis when false negatives are generated during biometric identification processes of migrants (La Fors-Owczynik 2016; La Fors-Owczynik and Van der Ploeg 2015) or false positives of suspects (Tims 2015). However, justice as a value also plays an important role in both the implementation and application stage. Given that big data accelerates the speed and quantity of data transfer and creates immense possibilities for reuse, instances for false identity verification, false accusation or stigmatization as a consequence of big data-led correlations also grow. Second, universal usability as a value on the VSD list refers to making persons successful users of information technology. Although success is a highly contested notion, we consider here a mutually respectful and just design and application of big data technologies holistically by all stakeholders as a form of success. All in all, justice is a value that is central to all stages of the big data life cycle.

Accountability

Accountability is a value that requires constant assessment in democratic societies (Braithwaite 2006; Jos and Tompkins 2004). From the four lists of values, accountability is explicitly stated only on the list of value-sensitive design. In VSD accountability refers to the properties, which facilitate that the actions of a person or institution are traceable to that person or institution. The technomoral value ‘perspective’ encompasses pivotal qualities for upholding accountability. As Vallor argues ‘perspective’ means the acknowledgement that emerging technologies will have implications that are “global in scale and unforeseeable in depth”. Cultivating perspective (holding on to the moral whole) as a value, Vallor argues, is necessary because by doing it we acknowledge that the emerging technologies we continuously develop have implications that are unparalleled, global in scale and perhaps unforeseeable in depth. Accountability as a value does not appear on the value list of anticipatory emerging technologies and of biomedical ethics.

Yet, given our integrated approach for big data technologies and the fact that the techno-social choices for and implications of using big data technologies increasingly magnify, accountability is a pivotal value on our list for big data. Transparency is a facilitator of accountability, in a similar way as it is a key condition for autonomy. If transparency is under pressure in domains of big data, so is accountability. For instance, auto-tagging instances can result in highly discriminative and offensive outcomes and put pressure on this value. Instances, when for example, two black persons have been tagged as gorillas (Gray 2015) or when the Dachau concentration camp has been tagged as a sport centre on a web-site (Hern 2015) demonstrates pressure upon the value of accountability. It is difficult to identify which parties in these big data mediated contexts are responsible for such offensive outcomes. Is it the algorithm, the designer, the user of a certain programme or also those searching users from whom an algorithm learns, or perhaps more of them? Given our holistic approach we consider that accountability is a pivotal value to uphold within all big data contexts, yet it pre-requires more transparent structures in big data networks and efforts from all stakeholders.

Trustworthiness

Trustworthiness is a value that requires mutual caring especially in a networked world (Keymolen 2016). From our four lists only VSD refers to this value, more specifically to trust. In VSD trust is described through the expectations that exist between people who can experience good will, act with good will toward others, feel vulnerable, and experience betrayal. Honesty and self-control are values on the list of technomoral values that are closest in notion to trustworthiness. Honesty and self-control can be regarded as qualities of a person upon which his/her trustworthiness can rely. On the anticipatory emerging technology ethics list no trustworthiness, honesty or trust is mentioned. On the biomedical ethics lists we consider veracity—telling the truth—as most closely related to trustworthiness.

As to honesty from the techno-moral value list, although the parameters of one general truth are quite difficult if not impossible to outline as Vallor points out, because the truth content of a message can change by to whom we speak, where we gather our information or how we present it. Still the intention of speaking with honesty within the context of big data is a desirable quality, because honesty (‘respecting truth’) serves flourishing in interactions with other people. Vallor argues that upholding honesty shall be the primary task of ethics, because human flourishing would be “impossible without the general expectation of honesty”. In this respect honesty is also connected to self-control. Vallor explains self-control as a person’s “ability to align one’s desire with the good” that includes good will and good intention. Both honesty and self-control underpin trustworthiness and only increase its relevance for big data contexts. Regarding the biomedical ethics list, trustworthiness is closely related to the value of veracity. The principle of veracity, when implemented as a moral requirement for big data collectors, data brokers, data scientists and other stakeholders would increase trustworthiness within relationships in big data networks. Therefore, given our integrated approach for big data contexts and the fact that trustworthiness is under constant pressure within big data contexts, to embrace trustworthiness holistically by all stakeholders is crucial. In particular, trustworthiness can become set under pressure in the application stage; for instance, because data transfer processes are obscure and citizens can easily become victims of precautionary algorithmic decisions as citizens are unable to refute the basis up which such decisions were drawn, see for instance occurrences of false positives in law enforcement (“False match shows no fly-list isn’t perfect,” 2010). Therefore upholding trustworthiness as a value is of utmost worth throughout all interactions in big data networks, and especially those that fall beyond the limitations of law. Given the relational character of this value—it can only flourish in interaction—prescribing the practice of trustworthiness (and also veracity) for all stakeholders during big data-based processes could, for instance, strengthen the effectivity of such legal prescriptions as informed consent (Custers et al. 2013, 2014); the right not to be subject to profiling or the right to explanation. These rights can easily be violated when trustworthiness, veracity and honesty are not effectuated in big data networks.

Solidarity

Solidarity as a value does not appear on any of the value lists referred to above. Yet, we consider solidarity as a highly relevant value in domains of big data (Tischner 2005). In VSD, the value of courtesy seems being the closest in notion to it. In VSD, courtesy refers to treating people with politeness and consideration.

Out of the technomoral value list empathy, flexibility, courage and civility relate most to solidarity as these values can be seen as building blocks to cultivate a mutually shared and upheld attitude of solidarity. Solidarity is a value which has been embraced to different degrees over time. For instance, before the fall of the iron curtain in Poland, solidarity became a value that assembled crowds, creating a new positive ideology of compassion and brotherhood against decades of Soviet political oppression. This symbolic but also enacted form of solidarity in today’s circumstances, at least in Western Europe, cannot be comparable as there is no oppression. Yet, the implications of showing/expressing solidarity in daily life by having the courage to come up for others and having the flexibility—the latter being closely related to the liberal value of tolerance according to Vallor—in order to “enable the co-flourishing of diverse human societies” is crucial to uphold during discussions on big data. Empathy (compassionate concern for others) as mentioned earlier is a value that cultivates openness to being morally moved to caring action by the emotions of the other members of our techno-social world. This is an essential quality of being solidaire with someone else. Flexibility as a techno moral value(skilful adaptation to change) is a highly useful enabler of solidarity as it facilitates the co-flourishing of diverse human societies and requires mutual cultivation. As to courage, solidarity requires courage from those who want to enact compassionate behaviour with others and therefore require risk taking and prioritizing interests with a goodwill for others. Solidarity also resonates with civility, which according to Vallor (making common cause) is the “sincere disposition to live well with one’s fellow citizens of a globally networked information society, to collectively and wisely deliberate about matters of local, national and global policy and to work cooperatively towards those goods of techno social life that we seek and expect to share with others”. Solidarity may also overlap with welfare (see above), because from some perspectives (such as Shannon’s technomoral values) both values are focused on a responsive disposition towards others. However, from other perspectives (such as VSD), welfare focuses more on individual well-being. Therefore, we include both welfare and solidarity as a separate values in our list, because welfare focuses more on the individual aspect and solidarity focuses more on the inter-relational, societal aspect.

Given these qualities underpinning solidarity as well as our integrated approach and holistic view on stakeholders, it is also highly important to stress that solidarity within big data networks requires mutually respectful cooperation of stakeholders. This can especially be seen as an asset when limitations for the use of novel big data technologies are scarce yet. Many instances of big data-based calculations in which commercial interests are prioritized versus non-profit interests, are examples of situations in which solidarity is under pressure. When, for instance, immigrants are screened by big data-based technologies, they may not have the legal, lingual, physical or psychological position or capacity to defend themselves from potential false accusations resulting from digital profiling. These are examples of solidarity being under pressure within big data-based interactions.

Environmental welfare

This value only appears as environmental sustainability on the list of value-sensitive design. The value list of biomedical ethics does not include it. On the list of techno moral values empathy and courage seem most closely related to it, and on the list of anticipatory emerging technology ethics ‘no environmental harm (including animal welfare)’ is closest in notion. On the list of VSD, environmental sustainability refers to sustaining ecosystems such that they meet the needs of the present without compromising future generations. The list of anticipatory emerging technology ethics contains no harm, this also entails the prohibition of causing environmental harm (including animal welfare). Among the techno moral values, empathy and courage seem to be the most closely related to environmental welfare. Although empathy has not been developed as a concept concerning non-humans, the environment (including animals), for instance, in Japanese (Callicott and McRae 2017) and tribal philosophies, such as the Native American culture (Booth 2008) or the South-African Ubuntu (Chuwa 2014) culture is highly respected, potentially as much as human life.

Given our integrated and holistic approach although big data has rather indirect effects on the environment, for instance the current rush for lithium in Latin-America (Frankel and Whoriskey 2016), which is the critical ingredient of all batteries on the world, shows how environmental welfare as a value is under pressure by big data technologies. Considering environmental welfare in big data contexts an environment conscious mind-set could help limit the negative implications of big data technologies throughout the whole big data life-cycle. For instance, the use of lithium based batteries puts pressure upon the value of environmental welfare. However, the wider use of solar energy-based batteries could limit the specific negative effects of big data technologies on the environment. Limiting such negative effects is also crucial, because any pressure upon the value of environmental welfare can also negatively affect human welfare.

Certainly our list including these ten values, summarized in Table 1, is not exhaustive. Yet, these ten value dimensions are comprehensive with respect to emerging big data technologies in multiple contexts. This value list is also aimed at providing value-specific perspectives for discussion. Such discussions could regard the extent to which using big data technologies brings along issues that put pressure upon pivotal ethical values in our current societies (Table 2). Human welfare, autonomy, non-maleficence, justice, accountability, trust, privacy, dignity, solidarity, environmental welfare are all values that are constantly under pressure within the context of big data and in our view deserve reflection throughout the circular life cycle of big data technologies in all contexts by the broadest range of stakeholders involved.

Conclusions

Emerging big data technologies are putting increasing pressure upon the boundaries of what can or cannot be considered acceptable from an ethical perspective. Important values like autonomy, non-discrimination, fairness, justice, privacy and human dignity are at stake. Although a lot of valuable research is already available on values under pressure of emerging big data technologies, it often does not take a holistic approach. This can be a miss, particularly when values are competing. More holistic approaches that are available usually focus on either a design-based approach, in which it is tried to implement values into the design of new technologies, or an application-based approach, in which it is tried to address the ways in which new technologies are used. However, there does not exist an integrated approach that covers the whole lifecycle of big data technologies. The neat theoretical distinction between different stages of technological innovation does not always exist in practice, especially not in the development of big data technologies. What is supposed to be a staged development process, from the flexible stage of invention or design to the more closed stage of adoption and use, in practice often is an iterative approach in which new technologies and new applications of existing technologies are built on each other. In such processes, the different stages are sometimes overlapping, sometimes non-sequential and sometimes running in parallel. Another miss in the existing literature is that none of the ethical approaches is specifically focused on big data and big data technologies. The existing approaches typically are somewhat general in nature, which offers a broad scope of applying them, but this may not always be tailored to the specific nature of big data related ethical issues.

In this paper we have integrated ethical values from existing design-based and application-based ethical approaches for new technologies and further focus this integrated result to the context of emerging big data technologies. A total of four value lists were selected for this integration: one list from techno moral values, one from value-sensitive design, one from anticipatory emerging technology ethics and one from biomedical ethics. This integrated list consists of a total of ten values: human welfare, autonomy, non-maleficence, justice, accountability, trustworthiness, privacy, dignity, solidarity and environmental welfare. Together, this set of integrated values provides a comprehensive and in-depth overview of the values that are to be taken into account for emerging big data technologies. As such, this integrated list of values challenges us to reflect on what human flourishing in the big data era comes down to, what the necessary conditions are to ensure this flourishing and what people need in order to bring these values in practice. This integrated, holistic approach allows all actors involved in emerging big data technologies, such as engineers, developers, designers, data scientists, users, data subjects, citizens, policy makers and legislators to consider where they can take joint responsibility.

This holistic integration of ethical values for big data contexts also supports the importance of carrying out societal impact assessments periodically. Things change rapidly in the area of big data technologies. Therefore, periodical assessments seem crucial. Also the fact that a lot of this is context-dependent and many values are interconnected calls for further research. To conclude, upholding these values should be regarded as a continuous goal to aspire to and as a mindset in practice throughout big data-mediated interactions.

Notes

Not to be confused with product life cycles in which products are intruded in markets and decline after the end of their life cycle. When referring to the circularity of big data life cycles we consider that data use involves a continuous learning curve with periodic reflections upon the original purposes of a given big data technology. Such reflection often includes changes, for instance, in prognostic criteria or even on more fundamental levels of technology design, in order to better meet new societal developments.

Biomedical ethics is generally considered as a professional, area-specific ethics. Yet, we included it as one of the four lists we identify values from for big data contexts. Given that through its main principles biomedical ethics, independently from contexts, prioritizes the utmost protection of human life, the applicability of its principles for big data contexts seems almost evident.

e-SIDES Workshop at the 23rd ICE/IEEE Conference, Madeira, June 28th 2017—Retrieved on 12th January 2018 from http://www.e-sides.eu/media/madeiraworkshop-presentation.

e-SIDES Workshop at CEPE/Ethicomp 2017 University of Torino—Retrieved on 12th January 2018 from http://www.e-sides.eu/media/turin-workshoppresentation.

e-SIDES Workshop at European Big Data Value Forum 2017 Towards Privacy-preserving Big Data—Retrieved on 12th January 2018 from http://www.esides.eu/news-events/e-sides-workshop-at-ebdvf-2017-towards-privacy-preserving-big-data.

As to technomoral wisdom, we will not dive deeply into this value, because as Vallor calls it: this is rather a “general condition of well-cultivated and integrated moral expertise” (Vallor 2016, p. 154) to navigate virtuously among emerging technologies. We acknowledge though that technomoral wisdom is served by all other eleven values and at the same time technomoral wisdom should also be enshrined in virtuous action in relation to emerging technologies, consequently also in relation to big data technologies.

Ibid.

These principles can be prioritized, but they need to be considered as prime convictions for any healthcare professional while carrying out his/her care duties.

They argue these principles during medical treatments are of additional value. The respect for dignity is considered as a value that should be applicable even to patients who are not able to take conscious decisions anymore. The principle of veracity is described when a ‘capable patient’ needs to acquire an as complete as possible ‘truth’ knowledge about his or her condition.