Abstract

This study investigates Japanese university students’ knowledge of labor laws using test theory and analyzes the determinants of understanding of labor laws. The college enrollment rate in recent years in Japan is over 50% of secondary education graduates, and as a result, college graduates are no longer considered elite employees. Rather, almost all graduates are merely ordinary workers. For that reason, students need to learn about their employment rights before obtaining initial employment to protect themselves and their future careers. However, there are few studies regarding Japanese university students’ knowledge of labor laws. This study, therefore, investigates their labor laws knowledge based on latent rank theory and analyzes the determinants by econometric analysis. Empirical results show that the average of correctly answered questions regarding Japanese labor laws is about 50%. I can view this record as not being positive because subjects start their job-hunting process with less than an ideal amount of legal knowledge. This research also confirms that there are positive correlations between some independent variables (for example, field of study, the number of credits regarding career education, experience with exploitive labor, and the number of friends who are older than a given subject) and the rank of labor law knowledge. This implies that education and experience regarding career development while enrolled in university correlates with better understanding of labor laws.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

This study attempts to investigate Japanese university students’ knowledge of labor laws using latent rank theory (LRT) and attempts to analyze the determinants of understanding of labor laws. In the Japanese labor market, the number of temporary workers has increased since the collapse of the bubble economy in the early 1990s. According to the Labor Force Survey, conducted by the Statistics Bureau of Japan, the percentage of non-regular workers in the labor force in 2021 was 53.6% for females and 21.8% for males. In addition, there is significant stagnation of real wage growth in Japan over the last few decades (Chun et al., 2021). Since the 1970s, moreover, the trade union density rate (the share of employees who are union members) has decreased, dropping to under 20% in recent years (Kato, 2016). Individualization of industrial relations continues to develop. Realistically speaking, the Japanese employment system, which is characterized as one based on long-term employment, a seniority-based wage system, and enterprise-based unions can no longer be expected to support employees’ career development. Since almost all enterprise-based unions consist of regular workers, the relationship between management and labor is not adversarial. Thus, unions have little power to resolve disputes over working conditions for workers in Japan.

Understanding of labor laws builds obvious core safety nets for workers in the labor market under current circumstances. Because a hierarchy between employer and employee exists in capitalist societies, labor laws have to be enacted in order to protect workers, and workers’ knowledge of labor laws is presupposed, in turn helping align employer-employee power dynamic balance. In fact, Barreiro (2018, p. 3) states that “the more you know about your legal rights in the workplace–to be paid fairly and on time, to do your job free from discrimination and retaliation, to work in a safe and healthy place–the more confident you will be in presenting your problem.” Assuming that knowledge of labor laws contributes to the mitigation of unemployment, discrimination, and harassment, I surmise that the determinants of the understanding of labor laws are a significant problem for vulnerable workers. Because knowledge of labor laws is a form of cognitive skill, it is not seen to be disconnected from education.

Since workers with only a secondary education are less competitive in the labor market, labor law education is obviously important for high school students. In recent years, however, labor law education for university students is also increasingly important. Although college enrollment rates in Japan are not high by international standards, that rate in recent years in Japan is over 50% for secondary school graduates (OECD, 2021). According to the School Basic Survey, conducted by Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), the number of job finders among new university graduates overtook that number of new high school graduates in 1998, and this gap continues to expand to the present (Fig. 1). College graduates are no longer thought of as elite employees; in fact, almost all university graduates are considered merely ordinary-level workers in Japan. Thus, in order to protect themselves and their future careers, university students need to learn their employment rights before obtaining initial employment.

Source: School Basic Survey, MEXT Note: This figure demonstrates the number of job finders among new graduates in Japan. The number of job finders among new high school graduates increased sharply after World War II. Since the 1970s, however, that number has decreased, dropping to under two hundred thousand in recent years. On the other hand, the number of job finders among new university graduates has increased and overtaken the number of new high school graduate employees in 1998. This gap continues to expand to the present

The Number of Job Finders among New Graduates in Japan.

On the other hand, the promotion of individual employment rights continues to develop in Japan. Since the 2008 financial crisis, exploitative companies that flout labor standards have become a significant social problem in Japan. Exploitative companies called “Burakku Kigyo” in Japan force harsh working conditions with long working hours, low wages, no overtime pay and other undue negative pressures on employees. Therefore, promoting individual employment rights creates momentum to protect workers from such exploitative companies, and improved labor law education is important as one solution to this issue. In response, the Labour Lawyers Association of Japan (LLAJ) issued a statement to promote legal education with regard to employment rights in 2013, after which, the Japanese government formalized an obligation to propagate basic knowledge of labor laws in high school and college education through the Partially Amending the Working Youth Welfare Act in 2015. The Japan Federation of Bar Associations (JFBA), moreover, submitted a written statement concerning labor law education to the MEXT, Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW), and Ministry of Justice (MOJ) in 2017.

Although this kind of promotion of individual employment rights creates momentum for change, there is little evidence regarding the actual understanding of labor laws and its determinants in Japan. In addition, previous research does not measure labor law knowledge based on test theory. Even though a majority of studies on the subject of labor law knowledge adapted observed scores gained through questionnaire surveys, they did not evaluate the quality of measures in terms of reliability and validity. In contrast, this study adopts LRT, which is a nonparametric test theory based on the self-organizing map or generative topographic map (Shojima, 2022), enabling a more reliable and accurate investigation of labor law knowledge.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows: the next section reviews relevant empirical studies regarding the understanding of labor laws; the following section introduces data and variables; the fourth section explains empirical methods; the fifth section introduces empirical results; and the final section presents conclusions.

Review of Literature

This section summarizes relevant literature that deals with the understanding of labor laws. In the United States, previous research has shown that many workers do not have sufficient knowledge regarding labor laws, even though employee rights were expanded with the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s. The American Federation of Labor—Congress of Industrial Organization (AFL—CIO) (2001, p.18) states that “in general, better-educated and better-paid workers have a more accurate understanding of their rights at work. However, a high percentage of these groups still overestimate the protections workers have on the job.” Estlund (2002) also points out the gap between employees’ beliefs and provisions of law. In the United Kingdom, Casebourne et al., (2006, p.1) conducted 1038 face-to-face interviews using computer-assisted personal interviewing, and they concluded: “groups that might be expected to be more vulnerable at work had lower levels of awareness and knowledge about their rights at work than other workers.” The results of these studies imply that even if governments enact additional labor legislation in order to protect workers, employees’ knowledge of labor laws might not be adequately accumulated. These studies, however, only analyze the level of labor law knowledge and do not investigate the determinants of understanding of those labor laws.

Martinez et al., (2007, p.8) explore demographic predictors for levels of employment law knowledge in U.S. Hispanic populations and conclude that “individuals who have more work experience, live in urban areas, and have a business college major, have greater levels of employment law knowledge.” Omar et al., (2009, p. 343) investigate the determinants of the level of labor law knowledge among banking employees in Malaysia and find that “there was a small difference in the level of knowledge between male and female; however, the level of knowledge increases with employees’ age, tenure, and level of education.” Although these studies reveal the demographic determinants of labor law knowledge, there is still room for statistical improvement, such as multivariable analysis, omitted variable bias, and evaluation based on test theory. More recently, although Sulphey et al. (2021) developed a measurement tool of labor law knowledge, researchers will have to accumulate more study results on the subject of measuring knowledge of labor laws.

In Japan, as mentioned previously, momentum to protect workers from exploitative companies increased after the 2008 financial crisis. Important research regarding employees’ or students’ knowledge of Japanese labor law also emerged around the same time. Takahashi (2008) analyzes the effects of legal knowledge regarding paid leave. This author reveals that employees of small companies have less legal knowledge regarding paid leave than employees of large companies; this implies that vulnerable workers in the labor market are not thoroughly educated. Takahashi (2008) also points out that if working environments are good, legal knowledge regarding paid leave facilitates the taking of paid leave. This study, however, only analyzes the legal knowledge of paid leave and does not investigate other aspects of labor laws.

Uenishi et al. (2014) and Umezaki et al. (2015) analyze the effects of Japanese university students’ understanding of labor laws on obtaining initial employment. These studies reveal that knowledge of labor laws correlates with likability for labor unions, and that understanding of labor laws facilitates obtaining employment at a company that has unions. The authors, however, could not elucidate a causal relationship between the knowledge of labor laws and likability for labor unions because of data limitations. Uenishi et al. (2016) and Nagumo et al. (2019) investigate the changing of individual’s labor law knowledge using longitudinal data in order to elucidate the problem of causal inference. The first survey was conducted when subjects were university students (third or fourth year students), and the second survey was conducted two years after the first survey. These studies reveal that on average subjects’ knowledge of labor laws did not improve during the time between the university and the workplace.

Hayashi (2014) also analyzes the effects of Japanese university students’ understanding of labor laws on obtaining initial employment. This author points out that although knowledge of labor laws does not increase the probability of obtaining initial employment directly, understanding of labor laws affects obtaining initial employment through the number of applications submitted during the job search process.

In summary, although direct effects of understanding of labor laws on labor market outcomes are not necessarily clearly perceived, there is at least a mediating effect that knowledge of labor laws affects labor market outcomes through the likability for labor unions or the number of applications submitted. There is, however, little literature regarding the determinants of understanding of labor laws in Japan. This study hopes to be unique and valuable research on the understanding of labor laws in Japan.

Data and Variables

Survey Outline

The data set used in this study was collected in December of 2021 by the Mynavi Corporation, a well-known Japanese college student recruitment agency that cooperated with this research. Mynavi collected original data regarding postgraduate and undergraduate students’ lifestyles through web monitoring questionnaire surveys. Subjects of this survey were Japanese university students (third year students) and master’s degree students (first year students). The number of returned surveys was 3,756. When this data were transferred from Mynavi Corporation to our research team, we kept personal information safe and secure in accordance with the Act on the Protection of Personal Information of Japan.

The Mynavi Corporation mainly deals with job recruitment in the private sector; therefore, this study targets students seeking employment in the private sector. In addition, this study only uses the data of undergraduate students in order to analyze understanding of labor laws using a relatively homogeneous subject group.

Dependent Variable

In this survey, data regarding knowledge of labor laws were collected. There were six questions in total, regarding job offers, working hours, overtime pay, paid leave, workplace accidents, and labor unions (see Table 1). As Nakayama (1995, p.3) points out, “the Trade Union Law, the Labor Relations Adjustment Law and the Labor Standards Law…compose the basis of the whole [of] Japanese labor law,” I created suitable questions to test the Japanese labor law knowledge of subjects, with a focus on the Labor Standards Law.

There were three answer options for each question, namely: 1) Correct; 2) Incorrect; and 3) I don’t know. Although there were exceptions, as a general rule the correct answer to each question was “2) Incorrect.” There is currently a categorical variable which can take on three different values. Both “correct” and “I do not know” are considered not correct answers. If the baseline value is not the correct answer, then the following dummy variable may be constructed:

Correct answer = 1 if individuals choose “incorrect” and 0 otherwise.

The question with the highest percentage of correct answers is Q2 (regarding working hours) with a result of 64.6%, whereas the question with the lowest percentage of correct answers is Q5 (regarding industrial accidents) with a result of 38.2% (see Table 2). One of the possible reasons for these results may be that while students are familiar with and have practical knowledge about working hours through part-time employment, students are unfamiliar with workplace accidents because of the generally low incidence of workplace injuries. The average of correctly answered questions is about 50%. This record is not positive because subjects start their job-hunting process with less than an ideal amount of legal knowledge.

Although the details of LRT are described later, in general the LRT is a test theory for grading academic achievement on an ordinal measurement scale. The dependent variable in this estimation, therefore, is the ordinal scale of knowledge regarding Japanese labor laws based on the information obtained from LRT.

Independent Variables

As mentioned earlier, because labor law knowledge is a form of cognitive skill, determinants of the understanding of labor laws is connected to education. This study, therefore, uses information regarding formal and informal education as independent variables, namely students’ major, career education, experience with exploitative labor, and number of friends.

The first independent variable is students’ choice of major. The more the opportunity for legal education is available, the more students will be able to obtain knowledge of labor laws. In other words, since a student’s level of labor law knowledge will be affected by field of study, students in law will usually obtain a higher mark in this area than will students who do not major in law.

The second independent variable is the number of credits regarding career education that have been completed. There was a comparatively smoother transition from university to workplace in Japan before the collapse of the bubble economy in the early 1990s. After that, many Japanese companies decreased recruitment of new university graduates as full-time employees and increased hires of non-regular employees. As a result, the employment rate of new college graduates deteriorated and has become significant social problem. As policy responses to this issue, the MEXT amended Standards for Establishment of Universities in 2010 and imposed the requirement that universities provide students with career education as part of regular curriculum or career guidance as extracurricular education. Since education regarding employment rights is comprised inherently of career education, the number of credits regarding career education affects students’ overall level of labor law knowledge.

The third independent variable is experience with exploitive labor. Many Japanese university students have part-time jobs. Since non-regular workers, as typified by part-time workers, are vulnerable workers in the labor market, they have a greater possibility to have experienced an exploitive workplace at some time. Therefore, when university students encounter an exploitive workplace, their labor law knowledge will expand for them to protect themselves. In this survey, data regarding experience with exploitive labor, such as long working hours, low wages, no overtime pay, harassment, and/or wrongful dismissal, were collected, and the resultant result was that 40% of subjects had hitherto had some experience with exploitive labor.

The fourth independent variable is the number of friends that a given subject has who are older than they. Almost all Japanese university students are barely of the age of majority and have little or no work experience, much less accumulated life experience. Therefore, they have a need for mentors who could help guide their life and/or the fulfillment of their career development. Thus, the number of older friends a given subject has will affect that subject’s level of labor law knowledge.

Control Variables

The control variables are gender, university rank, socio-economic status (SES), and, as a proxy for innate ability, high school grade point average (GPA). First, since gender difference in academic achievement is well-known based on the results of international assessments, such as Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) and Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS), this study employed gender difference as a control variable.

Second, if university rank is reflective of quality of education, university rank might correlate with the students’ knowledge of labor laws. Thus, this study employed university rank as a control variable. Ranking data of Japanese universities are collected from University Ranking, published by Asahi Shimbun Publications. Because this data includes university names as common information, it is possible to merge the data of this set with the Mynavi survey data sets. Japanese universities are ranked based on a practice examination conducted by Juku (cram schools). This test score is called Hensachi (similar to standardized test scores in America like the SAT, for example) and a score of 50 is the mean. Top universities have a higher Hensachi score.

Third, however, because university rank is an endogenous variable, omitted variable bias may occur. The most common omitted variables are SES and innate ability. If research does not control for subjects’ SES and individual-specific effects, findings are unable to adequately account for the following:

-

1.

Because personal abilities or SES is already high regardless of any education, students are better able to obtain higher levels of labor law knowledge.

-

2.

Because education of top universities is of high quality, students are better able to obtain higher levels of labor law knowledge.

-

3.

Because students have higher abilities or SES in the first place, they are able to go to top universities and can thus obtain greater knowledge of labor laws.

Omitted variable bias is a key problem for research on education. This study, therefore, uses individual information regarding SES and GPA obtained through questionnaire survey data to overcome omitted variable bias. If university rank and innate ability (or SES) are substitutes, higher university rank will significantly improve level of labor law knowledge when innate ability (or SES) is not included in the estimation. Table 3 provides brief descriptions of the variables used for the estimations and descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, minimum, and maximum).

Estimation Methods

Latent Rank Theory

LRT is a test theory for grading academic achievement not on a continuous scale but on an ordinal measurement scale. Shojima (2007) published important research on the origin of LRT. This author doubts that the ability of student A is higher than that of student B if the test score of student A is 80 and that of student B is 79. In fact, although there is a small difference in the academic achievement between the two students, there is a strong possibility this difference is within the margin of error. Therefore, Shojima (2008a, p. 1) may call the validity of a continuous scale as an evaluating tool for academic achievements into question and point out that scores on a continuous scale are an undesirable measure for evaluating academic achievements. This author said that a test is at best capable of classifying academic ability into 5–20 levels. In fact, professors give students their grades as follows: A + (excellent); A (good); B (average); C (passing); and F (failure).

Empirical analysis of LRT can be easily accomplished using the Exametrika software developed by the afore mentioned Kojiro Shojima. Exametrika can be downloaded from Shojima’s website (http://shojima.starfree.jp/exmk/). This study analyzes the understanding of labor laws using Exametrika version 5.5 in order to sort subject groups’ labor law knowledge.

Ordered Logistic Regression

Since the dependent variable is an ordinal measurement scale created by LRT, this study requires an ordered logistic regression model. I assume \({y}_{i}=j\left(1, 2, 3, 4, 5\right)\) for (poor, average, good, very good, excellent). The numbers from 1 to 5 do not have meaning in terms of these values, rather are just ordered from lowest to highest in the statistics. These categories are not equally spaced. For example, the difference between categories “poor” and “average” may not be the same as the difference between categories “average” and “good”.

Define \({y}^{*}\) as a latent continuous variable. The latent variable model is considered as follows:

where \(\alpha\) is an intercept term, \({x}_{i}\) stands for the independent variables, \({e}_{i}\) is the error term, and \(u\) is the cut-off point. The latent continuous variable \({y}^{*}\) is an unobserved variable. Although the latent continuous variable \({y}^{*}\) cannot be observed, we can observe \({y}_{i}\) when \({y}^{*}\) crosses thresholds. The choice rule, therefore, is as follows:

Incidentally, a rearrangement of the Eqs. (1) and (2) is as follows:

The probability that observation i will select alternative j is:

where F( ) is the cumulative distribution function of logistic distribution. Using generic representation, the respective probabilities for each category are described as follows:

This study attempts to analyze the determinants of the understanding of labor laws. All statistical analyses of ordered logistic regression were conducted using Stata version 17.0 (https://www.stata.com/).

Estimation Results

The number of latent ranks needs to be decided. There are six questions in total, the highest score value is six, and the lowest score value is zero. In short, there are seven possible scores from zero to six in the understanding of labor laws in this study. Therefore, there are a few candidate options for the number of latent ranks, namely 2, 3, 4, or 5. The number of the latent ranks was determined using fit indices, such as Akaike information criterion (AIC), conditional Akaike information criterion (CAIC) and Bayesian information criterion (BIC).

AIC, CAIC and BIC provide a basis for model selection. Information criterion scores can be used to determine which model is more likely to be appropriate for the same given data set. AIC, CAIC and BIC evaluate models relatively. As is well known, a lower AIC, CAIC and BIC score is better (Akaike, 1998; Bozdogan, 1987; Schwarz, 1978). As per the results, students were divided into five ordinal groups (see Table 4). Additionally, other indices are also generally passable.

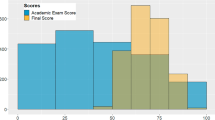

Item reference profile (IRP) calculated by Exametrika is used for interpreting the behaviors of the correct answer rate. IRP is a plot of the probability that a test item is answered correctly (see Table 5 and Fig. 2). Rank 1 consists of students who would likely not choose the correct answer for all questions. Rank 2 is composed of students who would likely not choose the correct answer for all questions, excepting Q2 (regarding working hours). Rank 3 is made up of students who choose the correct answer for Q2 and chose the correct answer for other questions on average, excepting Q5 (regarding workplace accidents). Rank 4 is comprised of students who were likely choose the correct answer for all questions, excepting Q5. Rank 5 consists of students who were likely to choose the correct answer for all questions.

In addition, weakly ordinal alignment condition (WOAC) is a prerequisite for latent rank analysis. Shojima (2008b, p. 5) points out that “the weak condition is satisfied when the test reference profile (TRP) is monotonically increasing but every IRP is not necessarily monotonic, where the TRP is the weighted sum of the IRPs of the test items.” According to Shojima’s (2008b) postulate, WOAC of my models were satisfied (see Fig. 2).

Estimation results of ordered logistic regression are presented in Table 6. I confirm the existence of omitted variable bias before observing the determinants of labor law knowledge. The first columns of Table 6 shows the results of my basic equation (Model 1). Model 2 includes SES while controlling for the variables included in Model 1, whereas Model 3 includes GPA in high school while controlling for the variables included in Model 1. Model 4 includes both SES and GPA in high school while controlling for the variables included in Model 1. Then, I find that the coefficient for university rank is depressed when SES and/or GPA in high school is added to it, and does not remain statistically significant in Models 3 and 4. In addition, I conducted the Chow test in order to test for whether or not each of the regression coefficients for university rank are equal (Chow, 1960). The Null hypnosis is that the coefficient for university rank in Model 1 equals the coefficient for university rank in Model 2 (or Model 3 or 4). The results of the Chow test determines that the coefficients are not equal between each equation. These results imply that although there is omitted variable bias when SES and/or GPA in high school is not included in the estimation, bias caused by omitted variables can be appropriately managed in this study.

The fourth column of Table 6, therefore, derives the adequate results. The empirical results of Model 4 show that there are positive correlations between independent variables (field of study, the number of credits regarding career education, experience with exploitive labor, and the number of friends who are older than a given subject) and the rank of labor law knowledge. The results were as I had expected. Considering the reasons I mentioned above, this study was able to adequately measure students’ knowledge of Japanese labor laws and analyze the determinants of labor law knowledge.

However, since interpreting the coefficients of ordered logistic regression is challenging in general, marginal effects need to be calculated in order to give a sense of magnitude. The marginal effects of Model 4, presented in Table 7, produce the following results: 1) the probability of obtaining rank 5 for students majoring in law is 11.6% higher than for students in the natural sciences; 2) an increase of one completed credit of career education increases the probability of obtaining rank 5 by 0.6%; 3) the probability of obtaining rank 5 for students who hitherto had had some experience with exploitive labor is 5.8% higher than for students having no experience with exploitive labor; and 4) an increase of one friend who is older than a given subject increases the probability of obtaining rank 5 by 0.2%.

Conclusion

This study attempted to investigate Japanese university students’ knowledge of labor laws using LRT. The result was that students are divided into five ordinal groups. The number of the latent ranks was adequately determined using fit indices. The average of correctly answered questions was about 50%. I can view this record as not positive because subjects start their job-hunting process with less than an ideal amount of legal knowledge. The question regarding working hours was easily answerable for students, whereas the question regarding industrial accidents proved to be significantly more difficult for the test subjects. Part of the reason for this difference seems to stem from variance among subjects’ prior workplace experiences.

This study also attempted to analyze the determinants of students’ understanding of labor laws. To summarize, this paper tested hypotheses, which are as follows: 1) field of study has influence on the level of labor law knowledge; 2) career education has impact on understanding of labor laws; 3) experience with exploitive labor in part-time jobs expands knowledge of labor laws, as such knowledge is necessary in order for students to protect themselves; and 4) the number of a student’s older friends affects knowledge of labor laws. Empirical results demonstrate that variables, such as field of study, the number of completed credits regarding career education, experience with exploitive labor, and the number of friends who are older than a given subject, remain positive and statistically significant after controlling for potential bias. This result verifies the original hypotheses.

The results of this study imply that education and experience regarding career development while being enrolled in university foster better understanding of labor laws. Although it is not surprising that students studying law obtain a higher mark in this area than do students who do not major in law, there is valid meaning in the effects of career education. As previously stated, the MEXT promoted educational reforms regarding career education after 2010 and the bar associations, such as the LLAJ and the JFBA, issued a statement to promote legal education with regard to employment rights around the same time. These educational policies and social movements, therefore, appear to be succeeding in promoting the obtaining of knowledge of employment rights for Japanese university students. Thus, education can be thought of as an important policy tool to help align employer-employee power dynamic balance.

On the other hand, the results of this study also indicate that informal education is an important factor of an increased level of labor law knowledge. While no experience with exploitive labor in a person’s part-time job experience is, of course, preferable, real-world experience has the potential to expand a student’s understanding of employment rights. In the case of work experience, older friends can serve an important function as mentors for students. Students might not be able to truly understand employment rights unless they actually experience the real world; thus, formal education and real-world experience are two of the most fundamental factors in learning and understanding employment rights.

However, I am unable at this time to reach anything beyond a tentative conclusion. Further research is needed to inspect the unsolved issues of where and when students should learn about Japanese labor laws and how they could more effectively become knowledgeable about those laws. Additionally, there are limitations to this study, namely that the results of this research cannot be interpreted as a causal relationship because of data limitations. The findings of this study, therefore, need to be carefully interpreted with these limitation in mind.

Data Availability

The data analyzed in this study are not publicly available due to its nature as confidential corporate information.

References

Akaike, H. (1998). Information Theory and an Extension of the Maximum Likelihood Principle. In: Parzen, E., Tanabe, K., Kitagawa, G. (eds) Selected Papers of Hirotugu Akaike. Springer Series in Statistics. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4612-1694-0_15.

American Federation of Labor—Congress of Industrial Organization (AFL—CIO). (2001). Workers' rights in America: What Workers Think about their Jobs and Employers. https://www.ibew.org/Portals/39/WorkersRightsinAmerica.pdf (accessed 24 November 2022).

Barreiro, S. (2018). Your Rights in the Workplace: An Employee’s Guide to Fair Treatment (11th ed.). Berkley, California: NOLO.

Bozdogan, H. (1987). Model Selection and Akaike’s Information Criterion (AIC): The General Theory and Its Analytical Extensions. Psychometrika, 52(3), 345–370. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02294361.

Casebourne, J., Regan, J., Neathey, F., & Tuohy, S. (2006). Employment Rights at Work: Survey of Employees 2005. The DTI Employment Relations Research Series, 51, 1–206. https://www.employment-studies.co.uk/resource/employment-rights-work (accessed 24 November 2022).

Chow, G. C. (1960). Tests of equality between sets of coefficients in two linear regressions. Econometrica, 28(3), 591–605. https://doi.org/10.2307/1910133.

Chun, H., Fukao, K., Kwon, H. U., & Park, J. (2021). Why Do Real Wages Stagnate in Japan and Korea? RIETI Discussion Paper Series, 21-E-010, 1–20. https://econpapers.repec.org/RePEc:eti:dpaper:21010 (accessed 24 November 2022).

Estlund, C. L. (2002). How Wrong Are Employees about Their Rights, and Why Does It Matter? New York University Law Review, 77(1), 6–35. https://www.nyulawreview.org/issues/volume-77-number-1/ (accessed 24 November 2022).

Hayashi, Y. (2014). Empirical Analysis of the Effects on University Students’ Job Hunting Behavior Based on Their Understanding of Workers’ Rights: Execution, Criteria and Success of Job Hunting. University Evaluation Review, 13, 135–145. https://id.ndl.go.jp/bib/000000391776 (published in Japanese, accessed 24 November 2022).

Kato, T. (2016). Productivity, Wages and Unions in Japan. ILO Conditions of Work and Employment Series, 63, 1–31. https://www.ilo.org/travail/info/publications/WCMS_465070/ (accessed 24 November 2022).

Martinez, P. G., Boykin, D. S., & Lengnick-Hall, M. L. (2007). Predictors of Employment Law Knowledge among Diverse Hispanic Populations. The Business Journal of Hispanic Research, 1(1), 1–12. https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/management_fac/12/ (accessed 24 November 2022).

Nagumo, C., Umezaki, O., Uenishi, M., & Goto, K. (2019). Acquiring and losing knowledge pertaining to work rules: A study on educational practices to counter loss of knowledge. Social Policy and Labor Studies, 10(3), 95–106. https://doi.org/10.24533/spls.10.3_95 (published in Japanese).

Nakayama, K. (1995). The Characteristics of the Japanese Labour Law and its Problems. Waseda Bulletin of Comparative Law, 14, 1–9. https://www.waseda.jp/folaw/icl/public/bulletin/back-number11-20/ (published in Japanese, accessed 24 November 2022).

OECD. (2021). Education at a Glance 2021: OECD Indicators. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/b35a14e5-en.

Omar, Z., Chan, K. Y., & Joned, R. (2009). Knowledge Concerning Employees’ Legal Rights at Work among Banking Employees in Malaysia. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, 21(4), 343–362. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10672-009-9123-5.

Schwarz, G. (1978). Estimating the dimension of a model. The Annals of Statistics, 6(2), 461–464. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2958889. Accessed 24 Nov 2022.

Shojima, K. (2022). Test Data Engineering: Latent Rank Analysis, Biclustering, and Bayesian Network. Springer.

Shojima, K. (2007). Neural Test Theory. DNC Research Note, 07–02, 1–10. http://shojima.starfree.jp/ntt/. Accessed 24 Nov 2022.

Shojima, K. (2008a). Neural Test Theory: A Latent Rank Theory for Analyzing Test Data. DNC Research Note, 08–01, 1–35. http://shojima.starfree.jp/ntt/ (accessed 24 November 2022).

Shojima, K. (2008b). The Batch-Type Neural Test Model: A Latent Rank Model with the Mechanism of Generative Topographic Mapping. DNC Research Note, 08–06, 1–28. http://shojima.starfree.jp/ntt/ (accessed 24 November 2022).

Sulphey, M. M., Alanzi, A. A., & Klepek, M. (2021). Development and Standardization of a Tool to Measure Knowledge of Labour Laws among Employees. E&M Economics and Management, 24(1), 86–104. https://doi.org/10.15240/tul/001/2021-4-006.

Takahashi, K. (2008). The Distribution and Function of Legal Knowledge about Paid Leave. The Journal of Ohara Institute for Social Research, 597, 50–66. https://dl.ndl.go.jp/info:ndljp/pid/9972487/1 (published in Japanese, accessed 24 November 2022).

Uenishi, M., Umezaki, O., Nagumo, C., & Goto, K. (2014). Development of College Students’ Perceptions of Work and Labor Unions, and the Impact of These Perceptions upon Their Job Search. Lifelong Learning and Career Studies, 11(2), 75–88. https://doi.org/10.15002/00009645 (published in Japanese).

Uenishi, M., Umezaki, O., Nagumo, C., & Goto, K. (2016). Changes in University Graduates’ Knowledge of Work Rules and Awareness of Labor Unions: Results of the Follow-up Survey. Lifelong Learning and Career Studies, 13(2), 67–81. https://doi.org/10.15002/00012819 (published in Japanese).

Umezaki, O., Uenishi, M., & Nagumo, C. (2015). The Impact of University Students’ Knowledge of Work Rules and Awareness of Labor Unions on Their Job Search Activities. The Japanese Journal of Labour Studies, 655, 73–82. https://dl.ndl.go.jp/info:ndljp/pid/10180482/1 (published in Japanese, accessed 24 November 2022).

Funding

This study was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI Grant Number JP19H00619.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author has no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hirao, T. Determinants of Understanding of Labor Laws: Evidence from Japanese University Students. Employ Respons Rights J 35, 437–454 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10672-023-09467-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10672-023-09467-0