Abstract

The increasing stakeholders’ scrutiny requires firms to communicate their non-financial performance to signal their commitment to sustainability. Building on the intention-based view and signalling, legitimacy and institutional theories, this study investigates whether corporate efforts to reduce information asymmetry and enhance their legitimacy led to higher quality and more transparent non-financial reporting practices. This study analyses reports from German, UK and Chinese companies over 14 years. It carries out quantitative and qualitative analysis of textual and visual content to evaluate disclosure density and accuracy of non-financial reports. The findings show limited progress in terms of the density and accuracy of the information disclosed by businesses since 2005. Also, they reveal cultural specificities in the reporting and approach to corporate social responsibility, along with a tendency to “create an appearance of legitimacy” by organisations. This study adds to the literature by studying the use of visual elements in non-financial reports. Moreover, it calls for strict policies and guidelines for the reporting of environmental and social issues by organisations. In particular, the inappropriate use of visual contents, the failure to provide quantitative information and managerial orientations show the need for completeness, transparency, and balance of information in reporting guidelines and regulations. The lack of authenticity and quality of the reports jeopardises the very purpose of non-financial reporting eroding trust in the system by all relevant social and economic stakeholders.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Stakeholders' vigilance regarding the social and environmental performance of businesses of all kinds has never been stronger (Diwan & Amarayil Sreeraman, 2023; Wong et al., 2023). This heightened scrutiny highlights the importance of the concept of legitimacy in shaping corporate behaviour, decision making and strategy (L’Abate et al., 2023). Thus, the ability of companies to demonstrate their alignment with prevailing social norms, values, and beliefs has emerged as an imperative for their survival (Ching & Gerab, 2017). This is particularly true as the economic market has entered an era of investment activism and responsible investment, compelling firms to adopt more socially responsible practices in order to maintain their current stock prices or secure low-cost funding opportunities (Bae et al., 2022; DesJardine et al., 2021). For example, in 2020 alone, 15 trillion dollars were divested from businesses engaging in controversial activities or practices (GSIA, 2021). In addition, in 2022, 40% of consumers made deliberate choices to align their purchases with their perception of a brand or business's environmental and societal impact (Deloitte UK, 2022), exemplifying a significant shift in societal values and norms.

Consequently, there is a clear mandate for firms to communicate their non-financial performance and to empower their stakeholders to evaluate companies' commitment to sustainability (Moratis, 2018). In that context, firms may use non-financial reporting as part of a strategy to construct and maintain their reputation, as well as signalling to their stakeholders their attention to environmental and social responsibilities (Ching & Gerab, 2017).

Non-financial reports are comprehensive documents that are meant to provide information about a company’s performance and practices in relation to sustainability factors. With these reports, firms aim to provide stakeholders with a holistic view of their sustainability practices. Therefore, such reports become an important signalling tool for firms to gain legitimacy and mitigate information asymmetry among their stakeholders (Wei et al., 2017).

Despite their perceived value, non-financial reports have various designations (e.g., corporate social responsibility report, citizenship report, sustainability report, environmental, social and governance reports, and environmental impact report), which suggests a lack of consensus on their definition and scope (Gulko & Hyde, 2022; Meuer et al., 2020). These different interpretations of what corporate environmental and social responsibilities are can make it difficult for stakeholders to understand and evaluate companies' commitments to social and environmental issues and leave room for strategic signalling practices (Michelon et al., 2014; Moratis, 2018). Indeed, a number of companies have been found to adopt strategies that seek to avoid full disclosure of non-financial information in efforts to protect themselves from external pressures (Michelon et al., 2014). Such strategies include the use of images (Hrasky, 2012; Kassinis & Panayiotou, 2018) and text (Mahoney et al., 2013) which are neither informative nor a reflection of the company’s commitment to environmental and social issues. In some cases, the information provided by the company lacks focus and drowns the reader in a “sea of insubstantial data” (Beretta & Bozzolan, 2008; Clarkson et al., 2008). Also, the symbolic power of images (Hrasky, 2012; Wang, 2012) is often used as “functional evidence” of the company’s CSR performance (Breitbarth et al., 2010).

Despite the diversity of scope in non-financial reporting resulting from individual companies’ interpretations of their social and environmental responsibilities, theories such as institutional theory suggest that competitive and institutional isomorphism can drive the standardisation of non-financial reporting practices across a broad spectrum of industries and cultural environments (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983). In that sense, sustainability reporting practices may not be driven only by business considerations but could be shaped by societal or institutional pressures (Hahn & Kühnen, 2013).

Building on the intention-based view and the signalling, legitimacy, and institutional theories, this study aims to examine the extent to which efforts by firms to reduce information asymmetry with stakeholders and gain legitimacy in the sustainability domain allow for more quality and transparency in non-financial reporting. Additionally, the study explores whether global isomorphic pressures have compelled companies worldwide to harmonise the content of their non-financial reports.

To do so, this study analyses how businesses in Europe and China have evolved over the last 2 decades in their approach to corporate social and environmental responsibility disclosure. The research contributes to the intention-based view and to signalling and legitimacy theories by providing empirical evidence of how information asymmetry and strategic communication manifest in non-financial reports and evolve over time and in different cultures. The findings also contribute to the institutional theory literature highlighting nuances in companies’ response to institutional pressures as it reveals isomorphism and divergence in both the quality of non-financial reports and their lexical and visual content across regions.

2 Literature review

2.1 Reporting practices and quality: signalling and attention based perspective

Signalling theory posits that companies (i.e., the signaller), aware of their sustainable practices, use non-financial reports as signal tools to communicate their social and environmental performance to meet their stakeholders (i.e., the receiver of the signal) expectations, to differentiate from competitors, and to establish legitimacy (Hahn & Kühnen, 2013). The content of these reports (i.e., the signal) mitigates information asymmetry in firms-stakeholders relationships by delivering relevant, transparent, and high-quality information to various parties (Bae et al., 2022; Ching & Gerab, 2017).

Moreover, according to the Attention-Based View, non-financial reporting practices can support organisations to convey their strategic competence, performance and signal credibility to external stakeholders (Ocasio et al., 2023). Indeed, non-financial reports encompass various aspects of a company’s social and environmental responsibility and can capture the attention of stakeholders and provide a platform for showcasing the organisation’s commitment to these domains. Consequently, the quality of non-financial reports can be seen as an indication of a firm dedication to society and the environment (Bae et al., 2022), and its capability to meet the receiver’s needs (Ching & Gerab, 2017; Martínez‐Ferrero et al., 2021; Moratis, 2018), thereby fostering trust and credibility with external stakeholders.

Two approaches to corporate social and environmental disclosure intent have been identified in the literature, namely symbolic and substantive approaches. A symbolic approach consists of companies trying to appear more efficient than they actually are by disclosing information that is solely qualitative and unbalanced, displaying “good numbers” (Maama & Mkhize, 2020) and failing to inform stakeholders genuinely(Clarkson et al., 2008; Xu et al., 2023). This strategic use of non-financial reports can lead to concerns about greenwashing practices (Amin et al., 2022; Hetze, 2016). In contrast, the substantive approach aims to inform stakeholders substantially and transparently, providing both quantitative and qualitative disclosure of the company’s objectives and results, and often demonstrating a high level of managerial commitment to effective and truthful reporting (Michelon et al., 2014; Xu et al., 2023).

However, while companies are asked to prove their good citizenship beyond mere compliance (Mitnick et al., 2023), 67% of investors believe that non-financial reports quality is poor or average (PwC, 2021) and 60% of them consider that companies should disclose more information (Nelson, 2017). Visser (2015) argues that addressing the current social and environmental crisis necessitates a shift in companies’ perspectives and strategies. This change involves moving from defensive and profit-focused strategies prioritising shareholder profits to transformative and robust approaches to their social and environmental responsibilities. Hence the analysis of the evolution of the quality of contents in their non-financial reports may identify signs of either a change in companies’ mindsets or, on the contrary, an anchoring of companies in old patterns. Therefore, this study explores the following research question:

Research question 1 To what extent do companies’ efforts to reduce information asymmetry with stakeholders in the domain of social and environmental issues allow for more quality and transparency in non-financial reporting?

2.2 Legitimacy theory and non-financial reporting: aligning firms’ efforts with societal expectations

While stakeholder theory addresses the different interest groups that influence a company, legitimacy theory more broadly refers to society as a whole that demands sustainable business conduct (Ching & Gerab, 2017). Legitimacy theory suggests that companies need society’s approval. Consequently, their ‘licence to operate’ can be threatened if society deems their actions unacceptable or inappropriate (Hahn & Kühnen, 2013; Hetze, 2016). Also, in order to maintain their legitimacy, companies must voluntarily align their activities with the values and norms of the wider social system of which they are a part (Ching & Gerab, 2017; Sun et al., 2022). As societal expectations may evolve over time, legitimacy in the corporate context is subject to continuous evaluation by the public. A “legitimacy gap” arises when an organisation’s values diverge from those of society, posing a risk to its credibility and societal acceptance. According to Sun et al. (2022) factors leading to a legitimacy gap can occur when there is a change in the organisation and also in societal expectations.

Based on the above, non-financial reports serve as a means for firms to establish and maintain legitimacy by demonstrating their alignment with the evolving expectations of society (Hetze, 2016; Martínez‐Ferrero et al., 2021). Therefore, this study explores the next research question:

Research question 2 How does the use of legitimacy strategies in non-financial reporting evolve over time to align with changing societal expectations for higher levels of corporate social responsibility and ethical practices?

2.3 Institutional theory and isomorphism in non-financial reports

To meet their stakeholders’ expectations, companies are expected to provide mature and credible non-financial reporting that is “sensitive to community standards and public expectations” (Heath & Palenchar, 2011, p. 332). Crawford and Williams (2011) state that “wise [firms] take note of both the regulatory and voluntary practices in their industry” (p. 342). Institutional theory emphasises the role of these external institutional forces on organisations’ behaviour. It suggests that companies may adapt their reporting practices to mimic those of their peers facing similar environmental conditions (Hahn & Kühnen, 2013; Sun et al., 2022). International initiatives such as the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) in promoting reporting standards seek to enable stakeholders access to non-financial information that is accurate and comparable (Schoeneborn et al., 2019). Additionally, country-of-origin effects play a crucial role in shaping corporate accountability practices, reflecting specific legislative and societal concerns in different regions (Fortanier et al., 2011). This highlights the importance of investigating the extent to which isomorphic pressures and international standards have led to harmonisation in non-financial reporting content. Moreover, the literature related to non-financial reporting is permeated by the perspective of the Western world (Whelan, 2007). Even though the definition of corporate social and environmental responsibilities has been found to vary between cultures (Kühn et al., 2015), little cross-regional analysis research has been carried out except for a small number of studies such as that of Vollero et al. (2022). Therefore, this study explores the following research question:

Research question 3 Have global isomorphic pressures compelled companies worldwide to harmonise the content of their non-financial reports across different culture?

2.4 Proposed theoretical framework

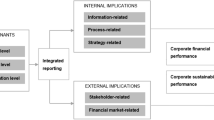

The theories of legitimacy and signalling both emphasise the importance of non-financial reporting as a strategic tool for companies to signal their commitment to social and environmental responsibility and to maintain a favourable image and acceptance by society. The concept of ‘signalling legitimacy’ derives from legitimacy theory and extends to signalling theory, as companies use the quality of sustainability reporting strategically to preserve and maintain their social status and project an image of concern for social responsibilities over time (Sun et al., 2022). Legitimacy theory and institutional theory share a common philosophy, both theories consider organisations as integral components of a broader social system, highlighting their interconnectedness with society at large. Additionally, these theories allow to explore firms’ strategies and mechanisms to adapt to shifting norms and expectations from their stakeholders, impacting the content of their non-financial reports (Sun et al., 2022). Based on the Attention-Based View, qualitative and transparent non-financial reporting practices can provide evidence of a firm's awareness of the dynamic nature of societal expectations and the attention it allocates to these evolving expectations (Ocasio et al., 2023). Thus, non-financial reporting reflects a company's recognition of the changing landscape of social and environmental concerns and its proactive efforts to address and communicate its responses to these shifts. Figure 1 summarises the proposed theoretical framework.

3 Methodology

This study performed a lexical and quality analysis of the text content in non-financial reports between 2005 and 2019 in China, Germany, and the UK. In addition, a quantitative and qualitative analysis of the evolution of the use of pictures was also performed.

3.1 Selection of the sample

3.1.1 Companies in the study

The sample of companies selected for this study was based on Breitbarth et al.’ (2010) study, which used sixteen reports produced by eight German and eight UK companies from eight different industry sectors. As described in Table 1, the original sample has been extended to include Chinese companies. This addition was driven by the Eurocentric nature of non-financial report literature (Whelan, 2007) and Gao (2011) and Li's (2016) argument that investigating Chinese companies' reporting practices may extend our understanding of corporate social and environmental responsibilities. To do so, companies listed on the Shanghai and Hong Kong Stock Exchange have been identified. The Chinese companies have been selected based on the industry sectors associated with the companies of Breitbarth et al. (2010) sample. To allow the analysis in the evolution of reporting practices, companies had to have been publishing non-financial reports for at least 4 years to allow comparison over time and that were written in English and downloadable.

3.1.2 Reports studied

To allow for the investigation of the evolution of the non-financial reports in time, the sample comprises two periods:

-

Sample 1 The first part of the non-financial report sample consists of the reports analysed by Breitbarth et al. (2010), and the non-financial reports produced by selected Chinese companies written between 2005 and 2010.

-

Sample 2 The second part of the sample consists of the most recent non-financial reports of the companies of the sample produced from 2011 and 2019 (see Table 1). It was not possible to find a non-financial report after 2011 for British Airways due to its merger with Iberia in 2011 to form the International Airline Group.

3.2 Analysis of the quality of information disclosed by companies

As shown in Table 2, studies have aimed to create methods to measure the quality of reports through different means such as Quality index, Latent Dirichlet Allocation analyses, Quantitative analysis and non-financial scores.

According to the GRI, clarity is one of the reporting principles for ensuring the quality of information disclosed in non-financial reports (Global Reporting Initiative, 2024). Also reports should “contain the level of information required by stakeholders but avoid excessive and unnecessary detail” (p. 14). However, as seen in Sect. 2.1, companies may sometimes use disclosure strategies (Hopwood, 2009) and may drown the reader in a "sea" of insubstantial data. Moreover, according to Adams (2004), companies need to provide non-financial reports that state values “with corresponding objectives and quantified targets with expected achievement dates. Companies should then report performance against those targets” (p. 732). Bouten et al. (2011) support this argument by defining the “comprehensiveness” of non-financial reports in terms of the extent to which goals, objectives and outcomes are disclosed.

Based on the above, in order to address the research question 1 and assess the overall clarity and quality (Qualityit) of non-financial reports, this study examines three key attributes based on Michelon et al.’s (2014) (see Table 3):

-

Report density A density index (\({{\varvec{D}}{\varvec{E}}{\varvec{N}}}_{{\varvec{i}}{\varvec{t}}}\)) was defined as the number of words devoted to social and environmental information relative to the total word count. A higher density score indicates higher clarity and transparency.

-

Accuracy A accuracy index (ACCit) was used to assess whether the information disclosed in the report is qualitative, quantitative, or monetary. It was determined as the ratio between the sum of the weighted value of all the extract of a non-financial report that contains social or environmental information (monetary disclosures weighted 3 points, quantitative disclosures 2 points, and qualitative disclosures 1 point), over the number of words in social- or environmental-related sentences contained in reports.

-

Managerial orientation A managerial Index (MANit) assesed the extent to which report display managerial objectives and outcomes was used to measures the number of words included in extract of a non-financial report relating to social or environmental information that contains goals and objectives (\({{\varvec{O}}{\varvec{B}}{\varvec{J}}}_{{\varvec{i}}{\varvec{j}}{\varvec{t}}}\)) or results and outcomes (\({{\varvec{R}}{\varvec{E}}{\varvec{S}}}_{{\varvec{i}}{\varvec{j}}{\varvec{t}}}\)).

Additional indices were created to measure the quality of the information displayed specifically realted to social (Quality(soc)it) and environmental (Quality(env)it) content of the reports (see Table 4).

An extract from a non-financial report was considered to contain social or environmental information if the extract was related to the societal or environmental impacts of the company under study and could fit in the disclosures listed by the Specific Standard Disclosures of the GRI’s Sustainability Reporting Guideline (G4). The coding of the reports was carried out with NVivo (version 12) software. A copy of the codebook is presented in “Appendix”.

3.3 Lexical analysis of non-financial reports

Landrum (2018) proposed to assess how companies understand and engage with their corporate social and environmental responsibility based on the lexical analysis of social and environmental related content they present in their reports. Landrum’s (2018) model consists of five stages, each representing a different level of social and environmental commitment and engagement, ranging from a very weak approach (stage 1) to a very strong approach (stage 5) to corporate sustainability. Therefore, to address research questions 2 and 3, a lexical analysis of the non-financial reports in the sample was carried out using a keyword frequency analysis. A list of keywords was associated with different levels of corporate social and environmental responsibility approach as in Landrum and Ohsowski’s (2018) study. Moreover, a conventional content analysis (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005) of the reports revealed a new set of keywords which were used to complement the initial list (Table 5).

The presence or absence of the keywords related to different stages of the Landrum Framework was assessed within each report using NVivo software. The dominant stage of the Landrum Framework for each report was determined by comparing the number of words associated with each stage. An example of this process is presented in Table 6.

In this example, Air China's 2009 non-financial report presents a business-centric approach to sustainability, while its 2017 report presents a systemic approach to sustainability.

3.4 Picture analysis

According to Barthes (1980), pictures are not code-free. Instead, under their veil of objective and neutral representation (Kress & Leeuwen, 2006), images are a powerful communication tool for companies which allow them to attract the readers’ attention (Hrasky, 2012), anchor storytelling (Dhanesh & Rahman, 2021), and build trust (Wang, 2012). Pictures can improve the transparency of non-financial reporting and communication with stakeholders by making complex concepts accessible to readers (Ali et al., 2020; Catellani, 2015). However, pictures may also be used for greenwashing purposes and to “create the appearance of legitimacy” by changing the perception of contents expressed in text form and providing an “idealised representation” of the company and an illusion of performance (Boiral, 2013; Chong et al., 2018). Many studies have focused on the textual content of non-financial reports, and little attention has been paid to their visual content (Jones et al., 2017) or to whether companies have changed their approach to their social and environmental responsibilities in visual and symbolic terms. Besides, no study has been found to respond to Breitbarth et al., and and’s (2010, p. 255) call for studying the use of pictures “in combination with written statements”. Moreover, this study addresses Zeng et al.’s (2022) call to examine the use of images in non-financial reports while also assessing their evolution and integration into the broader written discourse of companies on social and environmental responsibilities. We do this through a qualitative and quantitative analysis of images contained in non-financial reports assessing whether companies use identical visual languages to address social and environmental issues in their non-financial reports.

Therefore, to address research questions 2 and 3, a summative analysis was performed to study all reports' absolute and relative number of images. Additionally, the image density (\({DEN(pic)}_{it}\)) for each page of each individual reports using the area in question was measured as follows:

\(DEN\left( {pic} \right)_{it} = \frac{1}{{m_{it} }}\mathop \sum \limits_{l = 1}^{{m_{it} }} SI_{ilt}\) | The density of pictures in a specific report (\(DEN\left( {pic} \right)_{it}\)) is the total surface occupied by pictures in a report \(i\), in a year \(t. SI_{ilt}\) = [0,1] where, \(l\) is a discrete variable between 0 and 100% |

According to Keim (1963), the caption added to a picture allows it to be read “without difficulty and error” (p: 43). Consequently, to assess companies' commitment to preventing reader misinterpretation of images, the study evaluated the presence or absence of captions for each image.

Finally, a qualitative content analysis of the pictures was performed based on the framework developed by Breitbarth et al. (2010). Each picture of the non-financial reports was categorised into one of the five categories of the framework (see Table 7 and Fig. 2). A Conventional Content Analysis was used for pictures that are not classifiable to identify new categories.

Example of image classification based on Breitbarth et al (2010) framework

4 Data analysis and results

In the following analysis: sample 1 refers to the oldest reports (prior to 2010), whilst sample 2 refers to the most recent reports (from 2011) from companies based in the UK, Germany and China.

4.1 Evolution of social and environmental responsibilities approach in samples 1 and 2

As shown in Fig. 3, the reports in sample 1 are anchored in a business-as-usual approach to their social and environmental responsibilities seeking to "doing less bad" and focusing on growth and consumption (Landrum, 2018, p. 302). Nature is considered as a resource that can be exploited for profit.

Percentage of representation of keywords related to each stage of Landrum’s Framework (2018) in non-financial reports of samples 1 and 2

Overall, sample 2 approach of corporate social and environmental responsibilities disclosed in the German and UK reports remains business-centred, while 4 of the most recent reports of Chinese companies have shifted to a systemic approach.

4.2 Evolution of the lexical approach to sustainability issues in samples 1 and 2

The keywords “risks” and “compliance” are the most used in the most recent reports of the three countries. For example, in its 2006 report, Bayer uses the term “risk” 33 times compared to 324 times in 2018. This can be partially explained in the German and UK reports by the increase in EU environmental and societal regulations such as the GDPR (2016), and for Chinese reports, by the 2014 revision of the People's Republic of China Environmental Protection Act, which aims to make "war on pollution" (French Embassy in China, 2017). However, in the most recent reports, a decrease in the occurrence of keywords such as: "shareholders", "market", and "stockholders" suggests the disengagement of companies from an economic vision of sustainability. Yet, the sustained use of terms such as "growth", "market", "profits", or "customer" in both samples shows that companies consider that their level of production must be increased to enable consumption and growth. Additionally, the increase in the use of the keyword “technology” shows that the companies share the idea that they can develop technologies that will be as effective as natural solutions to existing or emerging business challenges and opportunities (Landrum, 2018).

The keywords “collaboration”, “trust”, “cooperation”, and “partnership” are increasingly used in all three countries. For example, the DeutscheBank, in its 2006 report, used the terms "collaboration" and "cooperation" a total of 22 times versus 165 times in its 2018 report.

The use of the terms "sciences", “disruptive”, and "scientific" increased in the most recent reports in the three countries, suggesting that companies have renewed the way they operate moving toward a more scientific approach to their activity. However, the limited use of keywords such as "repair", "restoration", and “preservation” or equivalent terms suggest that companies are not necessarily moving towards a more regenerative approach to social and environmental issues (Landrum, 2018).

The appearance of the keyword "circular" in its economic meaning, in the most recent reports in the three countries confirms the awareness of companies of new business models and practices. Overall, the most recent non-financial reports of the sample "adopt an external perspective of sustainability for the improvement of humanity” and aim to “do more good” (2018, p. 302) but remain focused on production, growth and consumption.

4.3 The evolution of the use of pictures in non-financial reports

4.3.1 New categories of pictures

Content analysis allowed for the emergence of two new categories of pictures as an extension of Breitbarth et al’s (2010) framework called “nature protector” and “future & technology” (see Fig. 4) and defined in Table 8.

4.3.2 Size and relevance of pictures.

The analysis found that the number of images in reports has overall decreased in all three countries. It was also found that the average surface occupied by the pictures has decreased over time in the Chinese and German reports while the UK reports use fewer but larger images.

These results highlight a nuanced and context-dependent nature of illustrative practices in non-financial reporting that have been adopted by companies across the sample. They are consistent with Ruggiero and Bachiller (2023) study that reveals distinct approaches to illustration in the non-financial reports of Italian and Spanish energy companies. Finally, the categories “people” and “day-to-day business” alone provide more than half of the images included in the reports in the three countries. These two categories are characterised by using what has been described as "feel good" images showing smiling faces with a symbolic rather than informative purpose.

4.3.3 The use of captions

As shown in Table 9, pictures falling in the category "dream" have the least captions in all reports. This deliberate absence of captions serves the purpose of stimulating the readers’ imagination and inviting their own interpretation of the images. Consequently, these visuals are employed primarily to introduce symbolic rhetoric that complements the adjacent text. This approach prioritises the images' capacity to convey meaning beyond mere informational content related to the companies' actions and conduct. These findings align with the observations made by Breitbarth et al. (2010) and Chong et al. (2018), highlighting the significance of images and captions as integral components of "functional evidence" (Breitbarth et al., 2010, p. 255) pertaining to companies' societal and environmental performance.

In contrast, the noticeable rise in the use of captions accompanying images categorised as "nature protectors" suggests that these visuals serve a functional role in conveying pertinent information rather than being purely aesthetic elements detached from the textual content. Notably, the average surface area occupied by captioned images in all non-financial reports of the sample is approximately one-third the size of images lacking captions. This discrepancy in size implies that smaller images are more inclined to deliver supplementary information, while larger ones are often intended to assume a symbolic and aesthetic role.

4.4 The evolution of the quality of non-financial reports

4.4.1 Societal quality index

The Chinese reports have notably shifted their emphasis towards societal information, as evidenced by an increase in the average DEN(soc) index, which rose from 30 to 40%. Additionally, these reports exhibit an average Qual(soc) index of 0.25, surpassing the corresponding indices of German and UK company reports. However, the theme of “human rights” is rarely addressed in the Chinese reports, while it has become a greater concern for German and UK companies.

The UK reports in both samples provide the most quantitative and monetary information and the most specific social and environmental objectives and results.

4.4.2 Environmental quality index

The indexes revealed a significant increase in the density of environmental information in the UK reports, with the average DEN(env) index rising from 13 to 33%. In contrast, the Chinese and German reports exhibit limited evolution in both the density and quality of their environmental information. On average, the RES(env) index has increased across reports in all three countries.

Overall, the environmental information in samples 1 and 2 reports presents more objectives and results than those included in the societal information. However, the themes of "water", "biodiversity", "transport", and "materials" do not seem to be the main concerns for companies that are focused on their CO2 emissions and reducing their energy consumption. The analysis suggests that “waste” management is also becoming one of the major subjects of companies' preoccupation in recent reports.

4.4.3 Overall quality of non-financial reports

The data analysis presented in Table 10 suggests an improvement in the quality of Chinese and UK reports over time, whereas the quality of German reports has remained relatively stable. Notably, recent Chinese reports exhibit an average MAN(it) index of 0.2, which is higher than German reports and equivalent to UK reports.

Also, some companies provide high-quality social and environmental information. For example, British Sky Broadcasting and British Airways obtain the highest Environmental quality indices and the highest results, objective and quality societal indices. Other companies seem to place more focus on specific subjects, such as the case of Alibaba in its 2018 report, which contains 40% societal information versus 5% environmental information.

4.5 Combined analysis

This study found no direct correlation between the company's social and environmental issues approach and the quality index of their reports. Indeed, reports with a systemic social and environmental issues approach do not necessarily show a higher overall reporting quality than business-centric and compliance-centric reports. Furthermore, this study found no correlation between the reports' word count or number of pages and their quality. For example, recent reports from SKY and Tesco contain respectively 9676 and 15,074 words while having a similar Quality(it) Index of 0.39.

5 Discussion

This section discusses isomorphism in company reporting practices, particularly regarding to the type of social and environmental responsibilities approach adopted and the quality of the content of the report found in this study. In addition, the impact of external requirements on these reporting practices is examined.

5.1 Isomorphism in reporting practices?

There is evidence of some degree of isomorphism and convergence in the approach to social and environmental issues in the non-financial reports of generated by Chinese, German and UK firms over the 14 years across different regions. Indeed most of the reports are rooted in an economy-focused approach to social and environmental issues, illustrated by the high use of words such as “growth” or “profits. Also, the qualitative analysis of images across all reports reveals that most of these seek to somehow include humans and faces. This human-centred approach to social and environmental issues could be interpreted as the shared willingness of companies to convey a commitment to being good to society and their employees (Breitbarth et al., 2010).

However, differences were also found in how companies from different contexts approach non-financial reporting. First, the Chinese reports focus primarily on the societal issues, while the German and UK reports present a more balanced environmental and social content. Also, German and UK reports dedicate around 4% of their contents to human rights, aligning with Li's argument that European companies prioritise human rights in their social responsibilities definitions. In contrast, Chinese firms focus more on promoting harmonious societal development and positive employee communication in their non-financial reports, reflecting a different emphasis in their reporting practices.

Second, differences in the use of images in non-financial reporting practices have been identified, supporting the findings of Kassinis and Panayiotou (2018). Indeed, this study introduces two novel approaches adopted by companies, departing from the traditional human-centered perspective to embrace eco-centred and techno-centred visions of social and environmental issues. This shift is reflected in the increased usage of new image categories in their non-fiinancial reports, specifically "nature protector" and "future & technology." These results contrast with Breitbarth et al.’s (2010) conclusion that companies agree to define their social responsabilities as human centred.

5.2 Is non-financial reporting showing a stronger approach to social and environmental issues?

Non-financial reports disclose a weak approach to social and environmental issues that is business-oriented, considering that Mankind has control over Nature which they can exploit. The growing use of the terms "technology" and “science” in the most recent reports particularly emphasises this control over Nature. These results support other studies showing that self-interests drive companies (Ates, 2023; Milne & Gray, 2013). This “weak” vision is perceived as convenient for companies as it invites them to "adopt incremental improvements from the status quo without requiring substantial change" to their strategies and operations (Landrum & Ohsowski, 2018, p. 139). This status quo can be partly explained by Ihlen and Roper’s (2014) study that showed that some companies consider that they are no longer part of a journey to achieve sustainability but that they have already reached it. Besides, tensions can be exerted on the decision-making process of companies that must be able to meet the different expectations of their stakeholders some of which may conflict with sustainability. Also, this study found that terms related to the limitations of natural resources are rarely used in the reports suggesting that the companies studied are not likely to engage in a full co-evolutionary approach to social and environmental issues. Furthermore, our data show a weak visual representation of Nature in both samples studied, confirming the results of Bjørn et al. (2017), which indicate less than 1% of 9000 companies consider natural limitations a key issue in their sustainability strategy.

However, the results of this study contrast with Landrum and Ohsowski's (2018) conclusion, revealing that some reports stand out by proposing a stronger vision of social and environmental issues. Indeed, ten of the twenty reports of sample 2 have moved towards an Intermediate vision of social and environmental issues (Stage 3 of Landrum’s Framework). Particularly, it can be argued the Chinese reports "adopt an external perspective of sustainability for the improvement of humanity” and aim to “do more good” as expressed by Landrum (2018, p. 302). This new approach engages companies in wider value collaboration and cooperation with their stakeholders. This openness is illustrated in the British Sky Broadcasting report (2018), for example, by incorporating stakeholders’ inputs in their non-financial reports. Finally, this study reveals the emergence of new themes in reports such as the "circular economy" and an increase in the variety of words with a strong ecological focus like “ecosystem” and “life cycle”. This suggests a higher level of consideration to new processes and business models.

5.3 The need for a higher quality of non-financial reports

Despite an increase in the DEN (it) and MAN (it) indices, it remains difficult for the report readers to extract substantive social and environmental-related content as it is often “lost” in a body of irrelevant information. Indeed, whereas the most recent reports have increased their word count by an average of 24%, the amount of information directly related to sustainability did not increase in reports studied from companies in the UK and Germany. The DEN (it) index of Chinese reports is evolving positively but it is merely catching up (i.e., currently 52%) with the level of UK and German reports. Thus, overall the quality of the information in the reports has changed very litle since 2005 and remained low in the three countries, which is in line with Michelon et al.’s (2014) and Omair Alotaibi and Hussainey’s (2016) findings. These results also confirm that the quantity of information disclosed does not guarantee its quality.

However, it is notable that there are differences in quality between reports produced by companies in the same country. As an example, in sample 2, the report by British Sky Broadcasting obtains a Quality(it) index of 0.39, far from the 0.05 attained by GlaxoSmithKline, both of which are distant from the median Quality(it) index of the UK sample which is 0.20.

Similarly, this study has revealed differences in reporting across countries. Indeed, the most recent Chinese reports provide their stakeholders with more extensive and specific managerial orientations than German and UK companies do. The Chinese reports focus on societal issues, accounting on average for 40% of their content, compared to 12% for environmental issues. In contrast, UK companies seem to have gained expertise in environmental data disclosure in their recent reports. Finally, German reports maintain the same disclosure practices since 2005.

The results also reveal a strategic use of images. On the one hand, photographic messages can be used as “symbolic rhetoric" (Chong et al., 2018, p. 328) using repetition of “feel-good images” to anchor a righteous representation of the company in the mind of the readers (Davison, 2008). On the other hand, images are increasingly used to provide information rather than as an aesthetic element disconnected from the text.

5.4 The influence of external requirement on non financial reporting

Our results suggest mixed levels of influence of external requirements/demands on the content of reports. For example, the most recent reports have significantly increased their use of the keyword “risks”, which could be explained by the emergence of GRI guidelines (G4) which require companies to report their environmental and societal risks.

The study also highlights an increase in the use of terms related to regulations in all reports in sample 2. This can be explained in reports from the German and UK firms by the increase in EU environmental and societal regulations, such as the GDPR (2016) and the Non-financial Reporting Directive (NFRD). In reports from Chinese companies, the increase could be related to the 2014 revision of the People's Republic of China Environmental Protection Act, which aims to make "war on pollution" (French Embassy in China, 2017). Conversely, the absence of the term “offset” in the Chinese reports can be explained in part by the fact that China does not have an Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS), which in Europe has imposed a CO2 emissions cap since 2005. As Chinese ETS was implemented end of 2021 (Reuters, 2021) future research could assess its impact on non-financial reports disclosures. That is in line with Gulko and Hyde (2022) and Muhammad (2022) findings that show that regulation can positively impact the quality of non-financial reports and improve disclosure practices.

Despite the above analysis, other findings suggest that the impact of external requirements remains limited and that other forces seem to have a stronger influence on disclosure practices in reporting. In line with Costa et al.’s (2022), this study shows that common guidelines such GRI have not led to an isomorphism of reporting practices. However, these results contrast with Mion and Adaui's (2019) study, which found an improvement in report quality after implementing the Non-Financial Reporting Directive in Italy and Germany. Thus, further research is required to assess the impact of culture on reports disclosures under the same regulations and regarding the impact of different approaches to transposing and implementing regulations on non-financial reporting practices.

6 Limitations

Despite the rigorous approach to the methodology employed, this research is not exempt from limitations. First, the cumbersome analysis processes combining three different methodologies did not allow this sample to be extended to more than 40 reports. However, the sample was enough to confirm the evolution of the perception of the firm of their social and environmental responsibilities. The authors acknowledge that the industry and sector of the companies studied may have had an impact on their reporting practices. Second, the reports for German and Chinese companies are not studied in their original language, and therefore minor discrepancies between the original and the translated versions of the reports may have been present. Third, the comparison period of reports is not homogeneous due to the difficulty in finding Chinese reports older than 5 years. Fourth, the lexical analysis of the quality of the reports does not allow an evaluation of the companies’ non-financial performance. Finally, the measurement of report quality could have additional dimensions than those chosen for this study. The methodology used could be complemented through the use of new dimensions in future studies.

7 Conclusion

This study has assessed the evolution of the content and quality of non-financial reports since 2005 in Germany, UK and China. It addresses Mason and Mason’s (2012, p. 499) call “to examine, through time, the discursive choices of corporate environmental reports” by investigating the evolution of meaning across institutional textual and visual messages in non-financial reports. Hence, this study is part of what the authors hope to become an ongoing review of academics, policy and practice on the evolution of companies' approach to their social and environmental responsibilities and the quality and content of their non-financial reports to improve reporting practices and corporate citizenship.

Firstly, the systematic study of 1647 images in non-financial reports have confirmed that visual contents are essential components of non-financial reports, which can be used as significant source of functional evidence of companies’ non-financial performance (Anantharaman et al., 2021). Their use across the sample suggests a common willingness of companies to “create the appearance of legitimacy” (Hrasky, 2012), aiming to influence the perception of their stakeholders and emphasise their commitment to being good to society, regardless of the geographic, social or economic context where such companies operate. However, there is agreement in the literature on the fact that the use of images for greenwashing purposes in corporate communication strategy jeopardises the very purpose of non-financial reporting to reduce information asymmetry between companies and their stakeholders. Moreover, when engaging in symbolic reporting practices companies risk damaging their stakeholders’ perception about their legitimacy and reputation, thus failing to gain or sustain competitive advantage (De Jong et al., 2018).

In this context, our research highlights the need for policies and guidelines on good practices for the use of visual content in non-financial reports, as recently argued by Zeng et al. (2022). As a result, we also argue that there is a need for further research with a focus on the differences in visual disclosure strategies using different media outlets, such as social media, which are heavily reliant on visual artifacts. In fact, Kwon and Lee (2021) have argued that almost every non-financial communication on social media includes a visual-centric component.

Secondly, this study adds to Breitbarth et al.’s framework (2010) through the creation of two new categories of images to illustrate companies' approach to their commitment to sustainability namely “Nature protector” and “technology & future”. Therefore, we propose two distinct emerging approaches to sustainability by companies: one based on ecosystem protection and ecology and the second one based on technology as the tool for achieving a sustainable future. In doing so, our research paves the way for future research to explore how these different approaches may impact the non-financial performance of firms.

Third, as shown by Bhatia and Tuli (2015), non-financial reporting is a relatively new area for Chinese companies, whereas it has been established for longer in European countries. Thus, by showing that the most recent reports from Chinese companies present a more open vision of social responsibility and, on average, the same quality as the German and UK reports, our findings challenge the notion that corporate experience in non-financial reporting leads to a stronger approach to sustainability and a better-quality reporting.

Fourth, this study suggests that national regulations and culture have a direct impact on reporting practices by showing that reports from Chinese firms focus more on societal issues while the UK and German reports present a more balanced content between environmental and social aspects.

Fifth, this study challenges traditional reporting practices by presenting evidence of little or no progress in the quality of German and UK reports since 2005. The failure to provide quantitative information and managerial orientation demonstrates the need to strengthen the requirement for completeness, transparency, and balance of information through guidelines and regulations relating to non-financial reports. This lack of transparency and follow-through can question the authenticity of the reports (Ngai & Singh, 2021). Furthermore, the significant increase in the number of words without a simultaneous increase in the quality of sustainability-related information questions the readability and accessibility of the report for stakeholders. These results align with the findings from Wang et al. (2018), who suggest that reporting guidelines should include a readability test such as the Flesch Reading-Ease. Also, a pressure-opportunity-rationalisation triangle model can be used to explain how some companies may consider non-financial reports as advertising rather than a transparency tool (Kurpierz & Smith, 2020). Indeed, the present study suggests that the need to appear good can be regarded as pressure on companies, while the lack of homogenisation of reporting practices provides opportunities for companies to disclose poor quality non-financial reports.

Finally, no link has been found between the quality of reports and companies’ approach to their environmental and social responsibilities showing that companies with a strong approach to these issues face the same obstacles to disclosing quality information as companies with a weaker approach. The double edge of organisation theory, involving a vicious circle leading companies to reduce their disclosure to avoid stakeholders' backlashes, may explain this phenomenon (Ashforth & Gibbs, 1990). Also, Garcia-Torea et al.’s (2020) study suggests that current GRI guidelines do not provide the know-how to disclose; and therefore, scholars are encouraged to measure the contribution of new guidelines (e.g., integrated reporting) to the increase in substantive information in non-financial reports.

Abbreviations

- GRI:

-

Global Reporting Initiative (GRI)

References

Adams, C. A. (2004). The ethical, social and environmental reporting-performance portrayal gap. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 17(5), 731–757. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513570410567791

Ali, I., Lodhia, S., & Narayan, A. K. (2020). Value creation attempts via photographs in sustainability reporting: A legitimacy theory perspective. Meditari Accountancy Research, 29(2), 247–263. https://doi.org/10.1108/MEDAR-02-2020-0722/FULL/XML

Amin, M. H., Ali, H., & Mohamed, E. K. A. (2022). Corporate social responsibility disclosure on Twitter: Signalling or greenwashing? Evidence from the UK. International Journal of Finance & Economics. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijfe.2762

Anantharaman, D., Huang, D., & Zhao, K. (2021). Is a picture worth a thousand words? Image usage in CSR reports. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3722228

Ashforth, B. E., & Gibbs, B. W. (1990). The double-edge of organizational legitimation on JSTOR. Organization Science, 1(2), 177–194.

Ates, S. (2023). The credibility of corporate social responsibility reports: Evidence from the energy sector in emerging markets. Social Responsibility Journal, 19(4), 756–773. https://doi.org/10.1108/SRJ-04-2021-0149/FULL/PDF

Bae, J., Khimich, N., Kim, S., & Zur, E. (2022). Can green investments increase your green? Evidence from social hedge fund activists. Journal of Business Ethics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-022-05230-x

Barthes, R. (1980). La Chambre claire. Note sur la photographie (Edition de l’etoile). Gallimard. https://imagesociale.fr/5258.

Beretta, S., & Bozzolan, S. (2008). Quality versus quantity: The case of forward-looking disclosure. Journal of Accounting, Auditing and Finance, 23(3), 333–375. https://doi.org/10.1177/0148558x0802300304

Bhatia, A., & Tuli, S. (2015). Sustainability disclosure practices: A study of selected Chinese companies. Management and Labour Studies, 40(3–4), 268–283. https://doi.org/10.1177/0258042X15624994

Bjørn, A., Bey, N., Georg, S., Røpke, I., & Hauschild, M. Z. (2017). Is Earth recognized as a finite system in corporate responsibility reporting? Journal of Cleaner Production, 163, 106–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.12.095

Boiral, O. (2013). Sustainability reports as simulacra? A counter-account of A and A+ GRI reports. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 26(7), 1036–1071. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-04-2012-00998

Bouten, L., Everaert, P., Van Liedekerke, L., De Moor, L., & Christiaens, J. (2011). Corporate social responsibility reporting: A comprehensive picture? Accounting Forum, 35(3), 187–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.accfor.2011.06.007

Breitbarth, T., Harris, P., & Insch, A. (2010). Pictures at an exhibition revisited: Reflections on a typology of images used in the construction of corporate social responsibility and sustainability in non-financial corporate reporting. Journal of Public Affairs, 10, 238–257. https://doi.org/10.1002/pa.344

Catellani, A. (2015). Visual aspects of CSR reports: A semiotic and chronological case analysis (pp. 129–149). CECS-Publicacoes/EBooks. http://lasics.uminho.pt/ojs/index.php/cecs_ebooks/article/view/2083.

Ching, H. Y., & Gerab, F. (2017). Sustainability reports in Brazil through the lens of signaling, legitimacy and stakeholder theories. Social Responsibility Journal, 13(1), 95–110. https://doi.org/10.1108/SRJ-10-2015-0147

Chong, S., Narayan, A. K., & Ali, I. (2018). Photographs depicting CSR: Captured reality or creative illusion? Pacific Accounting Review, 31(3), 313–335. https://doi.org/10.1108/PAR-10-2017-0086

Clarkson, P. M., Li, Y., Richardson, G. D., & Vasvari, F. P. (2008). Revisiting the relation between environmental performance and environmental disclosure: An empirical analysis. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 33(4–5), 303–327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2007.05.003

Costa, E., Pesci, C., Andreaus, M., & Taufer, E. (2022). When a sector-specific standard for non-financial reporting is not enough: Evidence from microfinance institutions in Italy. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal. https://doi.org/10.1108/SAMPJ-06-2021-0253

Crawford, E. P., & Williams, C. C. (2011). Communicating corporate social responsibility through nonfinancial reports. In The handbook of communication and corporate social responsibility (pp. 338–357). Wiley-Blackwell. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118083246.ch17.

Davison, J. (2008). Rhetoric, repetition, reporting and the “dot.com” era: Words, pictures, intangibles. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 21(6), 791–826. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513570810893254

De Jong, M. D. T., Harkink, K. M., & Barth, S. (2018). Making green stuff? Effects of corporate greenwashing on consumers. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 32(1), 77–112. https://doi.org/10.1177/1050651917729863

Deloitte UK. (2022). Sustainability and consumer behaviour 2022. https://www2.deloitte.com/uk/en/pages/consumer-business/articles/sustainable-consumer.html.

DesJardine, M. R., Marti, E., & Durand, R. (2021). Why activist hedge funds target socially responsible firms: The reaction costs of signaling corporate social responsibility. Academy of Management Journal, 64(3), 851–872. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2019.0238

Dhanesh, G. S., & Rahman, N. (2021). Visual communication and public relations: Visual frame building strategies in war and conflict stories. Public Relations Review, 47(1), 102003. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PUBREV.2020.102003

DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095101

Diwan, H., & Amarayil Sreeraman, B. (2023). From financial reporting to ESG reporting: A bibliometric analysis of the evolution in corporate sustainability disclosures. Environment, Development and Sustainability. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-023-03249-2

Fortanier, F., Kolk, A., & Pinkse, J. (2011). Harmonization in CSR reporting. Management International Review, 51(5), 665–696. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11575-011-0089-9

French Embassy in China. (2017). Note sur le Droit de l’environnement en republique Populaire de Chine.

Gao, Y. (2011). CSR in an emerging country: a content analysis of CSR reports of listed companies. Baltic Journalof Management, 6(2), 263–291. https://doi.org/10.1108/17465261111131848.

Garcia-Torea, N., Fernandez-Feijoo, B., & De La Cuesta, M. (2020). CSR reporting communication: Defective reporting models or misapplication? Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 27(2), 952–968. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1858

Global Reporting Initiative (2024). GRI 1 : Foundation 2021.

Goloshchapova, I., Poon, S. H., Pritchard, M., & Reed, P. (2019). Corporate social responsibility reports: Topic analysis and big data approach. European Journal of Finance. https://doi.org/10.1080/1351847X.2019.1572637

GSIA. (2021). Global sustainable investment review 2020. www.robeco.com.

Gulko, N., & Hyde, C. (2022). Corporate perspectives on CSR disclosure: Audience, materiality, motivations. International Journal of Disclosure and Governance, 19(4), 389–412. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41310-022-00157-1

Hahn, R., & Kühnen, M. (2013). Determinants of sustainability reporting: A review of results, trends, theory, and opportunities in an expanding field of research. Journal of Cleaner Production, 59, 5–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2013.07.005

Heath, R. L., & Palenchar, M. J. (2011). Corporate (Social) responsibility and issues management: Motive and rationale for issue discourse and organizational change. In The handbook of communication and corporate social responsibility (pp. 315–337). Wiley-Blackwell. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118083246.ch16.

Hetze, K. (2016). Effects on the (CSR) reputation: CSR reporting discussed in the light of signalling and stakeholder perception theories. Corporate Reputation Review, 19(3), 281–296. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41299-016-0002-3

Hopwood, A. G. (2009). Accounting and the environment. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 34(3–4), 433–439. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2009.03.002.

Hrasky, S. (2012). Visual disclosure strategies adopted by more and less sustainability-driven companies. Accounting Forum, 36(3), 154–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.accfor.2012.02.001

Hsieh, H. F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687

Ihlen, Ø., & Roper, J. (2014). Corporate reports on sustainability and sustainable development: “We have arrived.” Sustainable Development, 22(1), 42–51. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.524

Jones, C., Meyer, R. E., Jancsary, D., & Hollerer, M. A. (2017). The material and visual basis of institutions. In C. Jones, R. E. Meyer, D. Jancsary, & M. A. Hollerer (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of organizational institutionalism (pp. 621–645). Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446280669.n24

Kassinis, G., & Panayiotou, A. (2018). Visuality as greenwashing: The case of BP and deepwater horizon. Organization and Environment, 31(1), 25–47. https://doi.org/10.1177/1086026616687014

Keim, J.-A. (1963). La photographie et sa légende. Communications, 2(1), 41–55. https://doi.org/10.3406/comm.1963.944

Kress, G., & van Leeuwen, T. (2006). Reading images: The grammar of visual design (2nd ed.). Routledge. https://www.abebooks.co.uk/9780415319157/Reading-Images-Grammar-Visual-Design-0415319153/plp.

Kühn, A. L., Stiglbauer, M., & Fifka, M. S. (2015). Contents and determinants of corporate social responsibility website reporting in Sub-Saharan Africa: A seven-country study. Business and Society, 57(3), 437–480. https://doi.org/10.1177/0007650315614234

Kurpierz, J. R., & Smith, K. (2020). The greenwashing triangle: Adapting tools from fraud to improve CSR reporting. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal, 11(6), 1075–1093. https://doi.org/10.1108/SAMPJ-10-2018-0272

Kwon, K., & Lee, J. (2021). Corporate social responsibility advertising in social media: A content analysis of the fashion industry’s CSR advertising on Instagram. Corporate Communications. https://doi.org/10.1108/CCIJ-01-2021-0016

L’Abate, V., Vitolla, F., Esposito, P., & Raimo, N. (2023). The drivers of sustainability disclosure practices in the airport industry: A legitimacy theory perspective. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 30(4), 1903–1916. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.2462

Landrum, N. E. (2018). Stages of corporate sustainability: Integrating the strong sustainability worldview. Organization and Environment, 31(4), 287–313. https://doi.org/10.1177/1086026617717456

Landrum, N. E., & Ohsowski, B. (2018). Identifying worldviews on corporate sustainability: A content analysis of corporate sustainability reports. Business Strategy and the Environment, 27(1), 128–151. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.1989

Li, J. N. (2016). CSR with Chinese characteristics: An examination of the meaning of corporate social responsibility in China on JSTOR. Journal of Corporate Citizenship, 61, 71–93.

Lock, I., & Seele, P. (2016). The credibility of CSR (corporate social responsibility) reports in Europe. Evidence from a quantitative content analysis in 11 countries. Journal of Cleaner Production. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.02.060

Maama, H., & Mkhize, M. (2020). Integrated reporting practice in a developing country—Ghana: Legitimacy or stakeholder oriented? International Journal of Disclosure and Governance, 17(4), 230–244. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41310-020-00092-z

Mahoney, L. S., Thorne, L., Cecil, L., & LaGore, W. (2013). A research note on standalone corporate social responsibility reports: Signaling or greenwashing? Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 24(4–5), 350–359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpa.2012.09.008

Martínez-Ferrero, J., Ruiz-Barbadillo, E., & Guidi, M. (2021). How capital markets assess the credibility and accuracy of CSR reporting: Exploring the effects of assurance quality and CSR restatement issuance. Business Ethics, the Environment & Responsibility, 30(4), 551–569. https://doi.org/10.1111/beer.12355

Mason, M., & Mason, R. D. (2012). Communicating a green corporate perspective: Ideological persuasion in the corporate environmental report. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 26(4), 479–506. https://doi.org/10.1177/1050651912448872

Meuer, J., Koelbel, J., & Hoffmann, V. H. (2020). On the nature of corporate sustainability. Organization and Environment, 33(3), 319–341. https://doi.org/10.1177/1086026619850180

Michelon, G., Pilonato, S., & Ricceri, F. (2014). CSR reporting practices and the quality of disclosure: An empirical analysis. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 33, 59–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpa.2014.10.003

Milne, M. J., & Gray, R. (2013). W(h)ither ecology? The triple bottom line, the global reporting initiative, and corporate sustainability reporting. Journal of Business Ethics, 118(1), 13–29. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1543-8

Mion, G., & Adaui, C. R. L. (2019). Mandatory nonfinancial disclosure and its consequences on the sustainability reporting quality of Italian and German companies. Sustainability (switzerland), 11(17), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11174612

Mitnick, B. M., Windsor, D., & Wood, D. J. (2023). Moral CSR. Business and Society, 62(1), 192–220. https://doi.org/10.1177/00076503221086881

Moratis, L. (2018). Signalling responsibility? Applying signalling theory to the ISO 26000 standard for social responsibility. Sustainability, 10(11), 4172. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10114172

Muhammad, A. (2022). Do Pakistani Corporate Governance reforms restore the relationship of trust on banking sector through good governance and disclosure practices. International Journal of Disclosure and Governance, 19(2), 176–203. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41310-021-00132-2

Nelson, M. (2017). Is your nonfinancial performance revealing the true value of your business? | EY - Global. https://www.ey.com/en_gl/assurance/is-your-nonfinancial-performance-revealing-the-true-value-of-your-business.

Ngai, C. S. B., & Singh, R. G. (2021). Operationalizing genuineness in CSR communication for public engagement on social media. Public Relations Review, 47(5), 102122. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PUBREV.2021.102122

Ocasio, W., Yakis-Douglas, B., Boynton, D., Laamanen, T., Rerup, C., Vaara, E., & Whittington, R. (2023). It’s a different world: A dialog on the attention-based view in a post-chandlerian world. Journal of Management Inquiry, 32(2), 107–119. https://doi.org/10.1177/10564926221103484

Omair Alotaibi, K., & Hussainey, K. (2016). Determinants of CSR disclosure quantity and quality: Evidence from non-financial listed firms in Saudi Arabia. International Journal of Disclosure and Governance, 13(4), 364–393. https://doi.org/10.1057/jdg.2016.2

Omar, B. F., & Alkayed, H. (2021). Corporate social responsibility extent and quality: Evidence from Jordan. Social Responsibility Journal, 17(8), 1193–1212. https://doi.org/10.1108/SRJ-01-2020-0009/FULL/XML

PwC. (2021). PwC’s Global investor survey. The economic realities of ESG. https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/issues/c-suite-insights/global-investor-survey.html.

Reuters. (2021). China’s national emissions trading may launch in mid-2021-Securities Time, Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-climatechange-ets-idINKBN29G083.

Ruggiero, P., & Bachiller, P. (2023). Seeing more than reading: The visual mode in utilities’ sustainability reports. Utilities Policy, 83, 101610. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jup.2023.101610

Schoeneborn, D., Morsing, M., & Crane, A. (2019). Formative perspectives on the relation between CSR communication and CSR practices: Pathways for walking, talking, and T(w)alking. Business and Society, 59(1), 5–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/0007650319845091

Sun, Y., Davey, H., Arunachalam, M., & Cao, Y. (2022). Towards a theoretical framework for the innovation in sustainability reporting: An integrated reporting perspective. Frontiers in Environmental Science. https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2022.935899

Venturelli, A., Caputo, F., Leopizzi, R., & Pizzi, S. (2019). The state of art of corporate social disclosure before the introduction of non-financial reporting directive: A cross country analysis. Social Responsibility Journal, 15(4), 409–423. https://doi.org/10.1108/SRJ-12-2017-0275

Visser, W. (2015). Sustainable frontiers: Unlocking change through business, leadership and innovation. South Yorkshire: Greenleaf Publishing Limited.

Vollero, A., Yin, J., & Siano, A. (2022). Convergence or divergence? A comparative analysis of CSR communication by leading firms in Asia, Europe, and North America. Public Relations Review, 48(1), 102142. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PUBREV.2021.102142

Wang, A. (2012). The visual priming effect of credit card advertising disclosure. International Journal of Disclosure and Governance, 9(4), 348–363. https://doi.org/10.1057/jdg.2011.25

Wang, Z., Hsieh, T. S., & Sarkis, J. (2018). CSR performance and the readability of CSR reports: Too good to be true? Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 25(1), 66–79. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1440

Wei, Z., Shen, H., Zhou, K. Z., & Li, J. J. (2017). How does environmental corporate social responsibility matter in a dysfunctional institutional environment? Evidence from China. Journal of Business Ethics, 140(2), 209–223. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2704-3

Whelan, G. (2007). Corporate Social Responsability in Asia: A confucian context. In The debate over corporate social responsability (pp. 105–118). Oxford University.

Wong, W.-K., Teh, B.-H., & Tan, S.-H. (2023). The influence of external stakeholders on environmental, social, and governance (ESG) reporting: Toward a conceptual framework for ESG disclosure. Foresight and STI Governance, 17(2), 9–20. https://doi.org/10.17323/2500-2597.2023.2.9.20

Xu, R., Liu, J., & Yang, D. (2023). The formation of reputation in CSR disclosure: The role of signal transmission and sensemaking processes of stakeholders. Sustainability, 15(12), 9418. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15129418

Zeng, X., Momin, M., & Nurunnabi, M. (2022). Photo disclosure in human rights issues by fortune companies: An impression management perspective. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal, 13(3), 568–599. https://doi.org/10.1108/SAMPJ-06-2019-0243

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Di Chiacchio, L., Vivian, B., Cegarra-Navarro, J. et al. The evolution of non-financial report quality and visual content: information asymmetry and strategic signalling: a cross-cultural perspective. Environ Dev Sustain (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-024-04779-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-024-04779-z