Abstract

Mine closure is a global challenge. To date, there has been no scientometric analysis of the mine closure literature. This paper uses a scientometric analysis to assess the literature on mine closure. We assessed 2078 papers published since 2002. There was a rapid increase in the research output, with 76% of the papers published in the last 10 years. We identify the journals and co-citation index of journals associated with mine closure research. Geography journals are prominent with 20% of papers, but there is also evidence of journals linked to mining and interdisciplinary journals. Four clusters of universities are working on mine closure (the University of Western Australia, the University of Queensland, the University of the Free State and the University of Alberta) and the co-citation index groups journals into three clusters (environmental and ecological concerns, environmental health, multidisciplinary issues). The co-citation index groups the themes into 20 clusters, which we have regrouped into five themes (health, environment, geography, society, and regulation/politics). We draw seven conclusions. Although original social science research focused on the impact of mining, (1) there is clear evidence of work focusing on mine closure and (2) this work is rapidly increasing. The geography remains important (3) but has negative effects. Despite the geographical focus, ideas and concepts are substantially integrated across the available work (4). Focusing on geographical journals might prevent work from being published in multidisciplinary journals (5). Papers linking theory and mine closure are limited (6) and the available work needs careful thought on planning closures in cities and communities (7).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Mine closure is a global challenge and has large-scale environmental and socio-economic consequences. Historically, companies had abandoned mines when the mine was no longer viable. Consequently, governments tightened mine closure regulations and prevented companies from abandoning mines. However, in contrast to the large investments in identifying potential mining areas for exploration, mine closure research needs more depth. This reality is strange considering the industry’s commitment to sustainable development and the government’s intentions to save environmental and social costs associated with mining. Therefore, a need exists to investigate the nature and scale of the mine closure literature. Mining has large-scale consequences for the environment and for communities living near mines. The environmental and social aspects of mining have received much attention in research. Yet the pressure for renewables associated with the transition will likely increase mining operations. Renewable energy will require increased mining of minerals associated with renewable energy (Svobodova et al., 2022). Yet mine closure holds renewed environmental and development challenges. How mines will address environmental and development concerns when closing will determine how sustainable the mining industry can be. Furthermore, the link between mining, climate change and the just transition requires appropriate mine closure to avoid the dark side of renewable energy. Mining companies realise this. For example, the International Council for Mining and Metals has made various documents and toolkits available to support mine closures.

Twenty years ago, the World Bank released a publication predicting mine closures in the developing world (World Bank, 2002). These predictions were never validated. Since the World Bank predictions, no more large-scale predictions have been made. The annual mine closure conferences in Australia have been instrumental in building a knowledge base on mine closure. Yet, this knowledge base is mostly in the hands of mining companies and it prioritises environmental aspects. The environmental focus is also visible in mine closure legislation, despite assuming the integration of environmental and social aspects (Vivoda & Kemp, 2019). At the same time, there is a small but growing body of work on the social aspects of mine closure (Bainton & Holcombe, 2018; Vivoda et al., 2019). However, mine closure does not always mean the shutting down of mine. Often mines are placed in care and maintenance. It allows time for selling the mine or should the commodity price increase, the company can reopen the mine. Care and maintenance save closure costs and buy the company time. Although mine closure planning has been integrated into mine lifecycle planning, this principle seldom forms part of local strategic plans or community responses (Van Asche et al., 2017). In addition, most of the mine closure knowledge lies within mining companies and is associated with the technical closure of mines, as opposed to dealing with the societal or local implications of closure.

As noted above, mine closure holds much risk for the mining industry’s intentions to become more sustainable. Yet, the research on mine closure shallow and irregular. There is a need for a more systematic understanding of this literature. Despite this emerging body of research, there have yet to be systematic analyses of the research on mine closure. This paper is the first attempt to provide a scientometric analysis of the mine closure literature. To date, Bainton and Holcombe’s (2018) attempt is the best but only focused on the social aspects. The paper’s main objective is to apply a scientometric analysis to the literature on mine closure, using a dataset compiled by Dimension (www.dimensions.ai). We mirror these results against the trends in the literature and evaluate the value of the scientometric analysis to understand mine closure literature.

2 Literature

The initial mine closure literature focused on the environmental aspects of mine closure. This environmental focus resulted from changing environmental legislation and rehabilitation requirements in many countries since the 1970s. There was a realisation that the environmental impact of mining extends far beyond mining life (Sengupta, 1993). Australia’s annual mine closure conference has mainstreamed mine closure literature despite its environmental focus and remains one of the main contributors to mine closure knowledge (Bainton & Holcombe, 2018). Several papers on the social aspects of mine closure have also emerged from the conference (for example, Digby, 2012). Overall, the literature’s coverage of the social aspects of mine closure remains small, but there has been a rapid increase over the last decade. Bainton and Holcombe (2018) made the first attempt to systemise this literature. We think the literature points to seven aspects relevant to our scientometric analysis.

First, the business intelligence on mine closure is small. This lack of intelligence stands in direct contrast to the extensive intelligence about potential mining sites and investments in exploration. In practice, predictions about mine closure are often inadequate, for two reasons: it is difficult to predict the long-term market price of a commodity and mines often find new ores that prolong mine life. We have already referred to the World Bank’s (2002) predictions. However, there were no follow-up studies to determine whether these closures did take place. Furthermore, the different regulatory contexts in various countries make these types of predictions difficult (Browne et al., 2011; Crous et al., 2021). Reporting requirements on mine closure have increased (see Crous et al., 2021), but often this is inconsistent (Laurence, 2002) or remains country-, site- or company-specific (Kozłowska-Woszczycka & Pactwa, 2022). The intelligence is usually not publicly available.

Second, there is often no full understanding of what constitutes mine closure. For example, companies often place mines in care and maintenance as the first step in closure (Bainton & Holcombe, 2018). Another indication of closure is when mines sell their mining rights to smaller companies. These companies’ cost structures often differ, enabling these smaller companies to mine profitably. However, these companies often struggle to comply with closure regulations and do not have the funds available for closure. In some cases, governments must take over these liabilities. Despite recent legislation changes, mine closure often historically meant abandoning the mine. For example, Watson and Olalde (2019) estimate that South Africa has more than 6000 abandoned mines. The problem is that current legislation is not applicable to these mines. This is a global problem.

Furthermore, there is a focus on mine closure and implications for nearby towns and cities related to the energy transition (Svobodova, 2022). This is despite many countries reverting to coal because of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. The imposed nature of this transition will result in workers losing their mining jobs and the towns and cities experiencing these shocks. In Europe, large state subsidies and welfare programmes accompanied mine closure. Yet it is unlikely that similar approaches would be possible in the cities and towns of the Global South (Marais et al., 2022).

There is a growing body of work on the regulatory aspects of mine closure (Manero et al., 2020; Stacey et al., 2010; Vivoda et al., 2019). The focus has largely been on land rehabilitation and ecological concerns (Tiemann et al., 2022) and financial assurance (Peck & Sinding, 2009). Less prominent in the legislation are the social aspects of closure. Many governments assume that mine closure policies should integrate environmental and social aspects of mine closure (Vivoda et al., 2019). Although this principle is commendable, it has the danger that mining companies and governments could view the social aspects as less important than environmental rehabilitation. The relationship between environmental and social aspects also requires attention (Stacey et al., 2010). Appropriate land rehabilitation is not only an attempt to restore the ecology but lays the foundation for new economies to develop. For example, rehabilitating mine dumps and tailings ensures land is available for fresh industrial and economic development. At the same time, unrehabilitated dumps and tailings present long-term environmental and social concerns (Limpitlaw, 2004). Increasingly unpredictable weather events exposure closed mines to new risks (Bjelkevik & Bohlin, 2021).

Fifth, the mining industry concentrates on investments when a mine starts (a front-end approach) and is less concerned with what happens when it closes (a back-end approach) (Crous et al., 2021; Vivoda et al., 2010). Mining companies make most investments before the mine starts. This front-end approach ignores closure or, at best, results in vague plans, despite improvements in the mining industry over the past 2 decades. Bainton and Holcombe (2018) argue that closure challenges the idea that mining can contribute to sustainable local and regional development. Although increasingly legislation requires financial assurance, in practice these amounts are often not enough, or companies find ways to avoid final accountability (Vivoda et al., 2019). In Africa especially, few governments enforce environmental or closure requirements (Morrison-Saunders, 2016). This front-end approach also applies to social investments and attempts to create a social licence to operate.

Six, most mining literature emphasises the disruption that mining brings and ignores the dependencies that mining creates over the long term. Although mine closure has not contributed to social disruption in the Global North (O’Conner & Ruddell, 2021), there is emerging evidence that closure contributes to social disruption in the Global South (Marais et al., 2022).

Companies and governments have improved the monitoring and evaluation of mine closure (Manero et al., 2020). This is especially related to the environmental aspects of mine closure, with water and wastewater management and biodiversity being central (Sobolewski et al., 2022). Yet, this monitoring and evaluation requires long-term commitment and funding. At the same time, predicting ecological or social recovery is difficult (Bjelkevik & Bohlin, 2021). There are doubts whether this is possible in the long-term (Zalesky & Capova, 2017), while the data is often only in the hands of the mining companies rather than being publicly available. Improved transparency associated with mine closure data is vital to ensure broader participation.

Increasingly mining companies realise that mine closure requires social engagement with local communities (Stacey et al., 2010). In addition, mine closure requires an understanding of dependencies on mining and the consequences of closure. Vivoda et al. (2019) provided a detail list of consequences.

Finally, evolutionary economic geography teaches us “the historical processes that explain the uneven development and transformation of economic landscapes” (Boschman & Frenken, 2010, p. 214). Although evolutionary economic geography provides an understand of mining-area development, it is less influential in the study of mine closure, its economic implications, and the potential to mitigate the effects of mine closure through economic diversification. The ability of mining areas to attract alternative forms of capital (outside of the mining industry) is “contingent upon the operation of a mining project” (Bainton & Halcombe, 2018, p. 468). For three reasons, new economic approaches outside mining are difficult: current mining investment, limited links to other industries and the uncertainties associated with closure. Mine closure literature on economic diversification should consider the implications associated with evolutionary economic geography.

In summary, although mine closure is a specific phase in the mine lifecycle, it is not the end of local mining impacts. The ecological and social effects of mining (including closure) will continue beyond mining operations. The capital-intensive nature of mining over the last 100 years has contributed to the scale and nature of mine closure challenges. The need to address both the environmental and social aspects of mine closure remain high and the claims about sustainable mining from mining companies will depend on how they close these mines.

3 Methods

3.1 Introduction

Bibliometrics assesses the depth and strength of a research paper, book or conference paper on a specific topic. Pritchard (Statistical Bibliography or bibliometrics?, 1969, p. 348) used the term first in 1969 and defined it as “the application of mathematics and statistical methods to books and other media of communication”. He proposed a shift from biographical statistics to bibliometrics. Scientometric analysis is a sub-division of bibliometric analysis. Scientometrics is the “quantitative study of science, communication in science, and science policy” (Hess, 1997, p. 75). Library and information sciences commonly use bibliometric and scientometric analyses (Sahoo et al., 2016). It is also commonly applied in computer studies, knowledge management, and the medical field, where there is a need for integrating new research findings (Ahmed et al., 2018; Correia et al., 2018; Dong et al., 2020) or taking stock of research in a specific field (Sharma & Lenka, 2022).

Bibliometrics is not without criticism. It overemphasises the concept of ‘publish or perish’ (Van Dalen, 2021) and quantity over quality (Sahel, 2011). Yet, bibliometric indicators and metrics have become a way for universities to increase their rankings. Often, it is also the main criticism of university rankings. Improvements in computer science addressed some criticisms. For example, CiteSpace is a statistical software package designed for conducting bibliometric and scientometric research. It clusters data by the degree of freedom and level of association based on node size, modularity Q and burst frequency, and the spotlight (Chen, 2016).

3.2 Paper retrieval

Figure 1 sets out our approach to acquiring papers. We used dimensions.ai as the dataset for analysis (Dimensions, 2022). Dimensions is the largest information dataset in the world. It has over 1.4 billion citations, 117 million publications, 6 million grants, 8 million datasets, 159 million online mentions, and 135 million patents. Furthermore, about 622,000 clinical trials, 583,000 policy documents and 117 million publications are available (Orduña-Malea & López-Cózar, 2018). Dimensions has information on grants, clinical trials with publications, patents and citation counts, and annual trends. It classifies research fields into 22 fields of research using the Australian and New Zealand Standard Research Classification.

We collected data using Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) from the following website: www.dimensions.ai (Sin et al., 2022). Figure 1 provides the exclusion and inclusion criteria based on the PRISMA technique, consistent with other bibliometric analyses. Following an initial literature review, we used the following five keywords: mine closure, mine completion, mine shutdown, mine removal, and mine containment.

We collected 14,679 papers in July 2021, using the keywords above (see Fig. 1). We reduced the search to include 2002–2021, which yielded 13,478 papers. We chose eight of the 22 research fields based on the topic (it was an attempt to reduce peripheral papers with little reference to our main focus), which reduced the number of papers to 3037. We further excluded 130 papers with the missing data, 43 conference proceedings, four editorial papers, 140 duplicates, and 12 book reviews. We were left with 2078 papers.

Table 1 summarises the keywords and the inclusion of papers per annum. The keyword ‘mine closure’ was used in 94.2% of the cases, followed by ‘mine removal’ (3.1%), ‘mine shutdown” (1.3%), ‘mine completion’ (0.8%), and mine containment (0.8%). The level of distribution demonstrates that, even if a scholar utilises the concept “mine closure” alone, the result generated will be acceptable.

3.3 Analysis

This study used www.dimensions.ai to analyse the 2078 articles. CiteSpace software is widely used to analyse tools for estimating scientometric data (Chen et al., 2016; Jayantha & Oladinrin, 2019). The software reduces human error and bias, gives credibility and ensures robust results. Citescape supports data precision, connectivity, homogeneity and cluster connectivity (Chen & Chang, 2018). Furthermore, it provides conceptual mappings and structural results like betweenness centrality, modularity Q and silhouette score (Chen, 2016). Betweenness centrality measures the relationship between two nodes (Brandes, 2001). Research shows that the higher the betweenness centrality index, the higher the chance of a relationship existing between two phenomena. Modularity Q measures the relevance of a cluster in network analysis or a community structure. The modularity test measures and identifies clusters in communities in a conceptual network. The silhouette score measures the reliability of the conceptual framework and a figure of 0.5 or higher is an appropriate or acceptable score (Chen, 2016). A score of 0.3 or lower is low. The silhouette score ranges from − 1 to 1, where 1 is the highest and − 1 is the lowest. The silhouette score in Figs. 2 and 3 is 0.9 for both figures, demonstrating statistically reliable results.

4 Results

4.1 Publications per annum

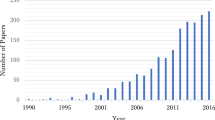

Table 1 provides an overview of the publications per annum with a rapid increase over the last 5 years. More than 50% of the publications in the database have appeared since 2016 and 76% appeared in the previous 10 years (2012–2021) (see Table 1). This increase in the research output shows how prominent mine closure literature has become.

4.2 Journal distribution and citation bursts

The journal choice has the most hits concerning the keywords (see Table 2). Choice is a review journal for new academic books and is not a purely academic journal.

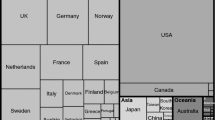

Five (20%) of the journals are geography journals. The geography journals in Australia and Canada are prominent, while polar geography has a more regional approach. The long histories of mining in Australia, Canada, and the polar regions are reflected in the prominence of these journals. There are two urban and regional studies journals related to the five geography journals: Urban Studies and Regional Studies. Concerning development studies journals, World Development and Development are on the list. Outside of geography, there are also discipline-specific journals for anthropology, economics, sociology, and political studies.

Although the list contains several resources and energy journals (Minerals, Journal of Sustainable Mining, Minerals and Energy—Raw Material Report, Energy Research & Social Science and Natural Resources Forum), two of the most prominent journals are absent. Resources Policy and Extractive Industries and Society have not made it into the top 25.

There are also several journals with a focus on environmental issues. This prominence of environmental journals is not strange considering the environmental concerns associated with mine closure. These journals include Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, Environmental Pollution, and Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability. The Canadian Journal of Zoology further shows the interdisciplinary nature of the research also presented on the list.

The following journals had the longest citation bursts (a citation burst refers to how a publication is linked to an increase in citation): Choice, Urban Studies, Economic Geography, Political Geography, Annual Review of Anthropology and the American Journal of Sociology. We also divided the journals into historical and current bursts. The six journals with current bursts (2021 and before) are Energy Research & Social Science, Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, Journal of Sustainable Mining, Nature Communications, Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, Minerals and Canadian Geographer. Three of these journals have an anergy focus highlighting the link between energy and mining and the mine closure requirements associated with the closure of coal mines to comply with a global reduction in CO2 emissions.

4.3 Institutions

Reference has already been made to the prominence of geography journals in Australia and Canada. The expectation is that authors from universities in these two countries would be prominent contributors. Figure 2 points to four clusters of universities. In the first two of these clusters, the Universities of Western Australia and Queensland are prominent in their contributions. These two clusters are close to one another and associated with some European (University of Barcelona), Canadian (University of Toronto), Chinese (China University of Geosciences), South African (University of the Witwatersrand) universities, and several other universities in Australia (Griffiths University, University of Melbourne and Curtin University). Environmental concerns associated with mine closure dominate the work, although some research focuses on the social aspects of mine closure.

Two prominent universities away from the main cluster of universities are the University of the Free State (South Africa) and the University of Alberta (Canada). Most of the work from these universities is related to planning, strategy development and mining towns and cities in these two countries. Often, these issues are being discussed in the context of mine closure. The work from the University of Alberta mostly uses evolutionary governance as a theoretical frame (Van Assche et al., 2020). Research at the University of the Free State focuses on mining towns and the social aspects of mine closure (Marais, 2013). This body of work is also relatively new (less than 10 years) but does bring interesting dimensions to the mine closure literature.

4.4 Co-citation analysis

The co-citation network shows three prominent clusters (see Fig. 3). Each cluster indicates high levels of co-citation. The first two clusters are journals associated with environmental and ecological issues, including restoration ecology, environmental and earth sciences, and environmental health perspectives. The third cluster contains a set of multidisciplinary journals, such as the Journal of Cleaner Production, Resources Policy, Energy Policy and Resources Conservation and Recycling. Two journals on the fringe of this third cluster are the Journal of Political Economy and the SSRN Electronic Journal. The three clusters show the research’s environmental and social divide (including the political issue).

4.5 Cluster analysis

Using cluster analysis, we created 20 themes and eight clusters. We have categorised it into five groups: health, environment, geography, society, and regulation/politics (see Table 3; Figs. 4 and 5).

The most impactful theme was #0 (resource companies) and the lowest was #19 (phytoremediation approaches).

The DCA on timelines, authors and spotlight illustrated in Fig. 5 exhibited the overall research development on mine closure for the 20 themes. For example, the green critique cluster (see Cluster #8) began around 1995 and ended in 2008. The mining or resource sector (Cluster #0) has the longest cluster, followed by Western Australia (Cluster #5), social mobilisation (Cluster #4), and environmental DNA (Cluster #3).

Larger nodes (called spotlight) were identified in clusters #:0, 1, 2 3, and 6. Spotlights are critical and helpful in determining high betweenness centrality, and where it fades, it is on account of low or marginal significance. However, one can attribute the growth of resource or mine research to decades of economic restructuring. While Cluster #1 (social licence) experienced a significant stride in 2013, the growth in research on Cluster #2 (northeastern Thailand) was witnessed in 2012. Although research on Cluster #3 (environmental DNA) grew significantly in 2012 and 2013, the lexicon of social identity in mine closure research became more prominent in 2013, and impactful research on the South African mining sector was between 2011 and 2013. There are examples of themes with significant citation burst and spotlight, like the mine and resource sector, northeastern Thailand, on environmental DNA had a significant relationship with publications on social mobilisation on Cluster #4.

5 Discussion

The evidence points to a wide range of research associated with mine closure and more extensive integration of ideas than we expected to find. For example, the evidence includes detailed work about the ecological effects of mining (Doley & Audit, 2016) and mine closure on specific species (Maiti, 2006). However, attention has also been given to broader environmental (Bjelkevik & Bohlin, 2021) and social aspects (Bainton & Holcombe, 2018).

Over the last 2 decades, there has been an increased volume of work on mine closure. The original social research concentrated exclusively on mine-community relationships during mine life. This sharpened focus on closure means that closure has become a major concern for companies and governments. Although an environmental focus dominates this work, the increase in work on the social aspects of the integration of social and ecological aspects related to closure is noteworthy (Bainton & Holcombe, 2018).

The results point to the importance of geography in the various themes. Not only are geography journals prominent, but geography per se is prominent. Countries in which historically mining is a major sector, like Australia, Canada, and South Africa, dominate the literature. It also means that the universities in these countries are prominent producers of these papers. The absence of work from Latin America is noteworthy, as our analysis only included papers in English. This result has two main implications: it emphasises the importance of local context and leaves many opportunities for comparative work. However, we think the geographical focus inhibits comparative work. For example, the two single-author books on mine closure only focus on two country-specific case studies: Malaysia (Chaloping-March, 2017) and South Africa (Marais, 2023). Admittedly, the one available edited collection has case studies from more than one country, although with a European focus (Neil et al., 1992). The lack of comparative work is notable, even though Fig. 3 points to close relationships between the works of some authors from different parts of the world. Comparative work is also complicated as it needs to account for different regulatory environments (Morrison-Suanders et al., 2016). In some countries in the Global South, enforcing these regulations is difficult (Morrison-Saunders et al., 2016). The closeness of the research clusters and co-citation between these clusters was an interesting finding. The inner circles of themes grouped around resource companies are noteworthy and point to the integration between ideas, authors, and geographies (despite the lack of comparative work outlined above).

Furthermore, the fact that one prominent mining journals, The Extractive Industries and Society, is not in the top 25 is noteworthy. We think two reasons contribute to it: the environmental focus, the emphasis on rehabilitation, and the dominance of geographers who emphasise geography and prefer to publish in geography journals and not in these multidisciplinary journals.

Although the research has a rich range of concepts, the themes do not reflect significant theoretical positions. The environmental nature and many case studies are the two most important reasons for this reality (Marais, 2023). The transition literature associated with the energy transition is an exception (Wang & Lo, 2021). Nevertheless, it is strange that concepts from evolutionary economics and evolutionary geography or institutional economics have not been used. Perhaps this points to the limited involvement of economists in this work and the dominance of geographers and other social researchers.

In conclusion, in several areas, insufficient work has been done. For example, there is little evidence of research focusing on how to plan closure outside the mining context. This reinforced the idea that mining companies and societies only consider mine closure at the back end of mining operations (Vivoda et al., 2019). Linked to this is how to transform mine infrastructure into other productive infrastructure at mine closure (see Pactwa et al., 2021, as an example). There is an emerging body of regional and urban case studies on the effect of mine closure, but detailed assessments of how to use mining infrastructure after mine closure remain inadequate.

Although much has been written on sustainable mining practices, the literature on mine closure adds to this.

6 Conclusion

We used scientometric analysis to understand the literature on mine closure better. The rapid increase in this literature over the past 10 years indicates the increasing importance of mine closures. The analysis points to a diverse set of research work that includes work with environmental and social implications.

Citations originate from many journals, with geography journals being prominent (especially in Australia and Canada). The wide range of journals also reflects the multidisciplinary nature of the research. We also identified four clusters of universities working on mine closure: two associated with universities in Australia (University of Queensland; University of Western Australia) and one each with universities in Canada (University of Alberta) and South Africa (University of the Free State). The co-citation index groups journals into three main clusters: two associated with environmental aspects and one with broader multidisciplinary journals. The co-citation index for themes group 20 clusters, which we have regrouped into five prominent themes.

The analysis does provide the first attempt to assess the broader literature on mine closure. We think we add to the existing literature in three ways. First, we emphasise the rapid growth and diverse nature of mine closure literature. Most of the work remains focused on the environmental aspects of closure. But there is an emergence of the social and economic aspects associated with closure. Second, we profile journals that publish work on mine closure and the universities involved in this research. The co-citation index also shows how journals and authors (within themes) co-cite. Thirdly, we can identify 20 clusters (and regroup them into five) and determine the co-citations of these themes over time.

Finally, we acknowledge three main limitations: the use of the English language appears only (excluding work from Southern America, which might be written in Spanish or Portuguese), the exclusion of some conference proceedings and an underemphasis on books and book chapters.

Data availability

The data will be made available on request.

References

Ahmed, R., Floody, J., Mohamed, A., Ragab, F., & Arisha, A. (2018). A scientometric analysis of knowledge management research and practice literature: 2003–2015. Knowledge Management Research & Practice, 16(1), 66–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/14778238.2017.1405776

Bainton, N., & Holcombe, S. (2018). A critical review of the social aspects of mine closure. Resource Policy, 59, 468–478. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2018.08.020

Bjelkevik, A., & Bohlin, T. (2021). Mine closure: Do we miss the opportunities? In: Fourie, A., Tibbett. M., & Sharkuu, A., Mine closure 2021: Proceedings of the 14th international conference on mine closure, QMC Group, Ulaanbaatar, https://doi.org/10.36487/ACG_repo/2152_89.

Bochma, R., & Koen, K. (2010). Evolutionary economic geography. In G. Clarke, M. Feldman, M. Gertler, & D. Wojcik (Eds.), The new oxford handbook of economic geography. Oxford University Press.

Brandes, U. (2001). A faster algorithm for betweenness centrality. The Journal of Mathematical Sociology, 25(2), 163–177. https://doi.org/10.1080/0022250X.2001.9990249

Browne, A., Stehlik, D., & Buckley, A. (2011). Social licences to operate: Or better not for worse; for richer not for poorer? The impacts of unplanned mining closure for “fence line” residential communities. Local Environment, 16(7), 707–725.

Chaloping-March, M. (2017). Social terrains of mine closure in the Philippines. Routledge.

Chen, C. (2016). CiteSpace: A practical guide for mapping scientific literature. Nova Publishers.

Chen, D., Liu, Z., Luo, Z., Webber, M., & Chen, J. (2016). Bibliometric and visualized analysis of energy research. Ecological Engineering, 90, 285–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoleng.2016.01.026

Correia, A., Paredes, H., & Fonseca, B. (2018). Scientometric analysis of scientific publications in CSCW. Scientometrics, 114, 31–89. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-017-2562-0

Crous, C., Owen, J., Marais, L., Khanyile, S., & Kemp, D. (2021). Public disclosure of mine closures by listed South African mining companies. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 28(3), 1032–1042.

Digby, C. (2012). Mine closure through the 21st century looking glass. In: A. Fourie (ed). Proceedings of the 7th international conference on mine closure. Australian Centre for Geomechanics, pp. 33–38.

Dimensions. (2022). Linked research data from idea to impact. https://www.dimensions.ai/.

Dong, J., Wei, W., Wang, C., Fu, Y., Li, J., & Peng, X. (2020). Research trends and hotspots in caregiver studies: A bibliometric and scientometric analysis of nursing journals. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 76(11), 2955–2970. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.14489

Hess, D. (1997). Science studies: An advanced introduction. New York University Press.

Jayantha, W., & Oladinrin, O. (2019). Bibliometric analysis of hedonic price model using CiteSpace. International Journal of Housing Markets and Analysis, 13(2), 357–371.

Kozłowska-Woszczycka, A., & Pactwa, K. (2022). Social license for closure: A Participatory approach to the management of the mine closure process. Sustainability, 14(11), 6610.

Laurence, D. (2002). Optimising mine closure outcomes for the community: Lessons learned. Mineral & Energy, 17, 27–34.

Limpitlaw, D. (2004). Mine closure as a framework for sutainable development. University of the Witwatersrand.

Maiti, S. (2006). Properties of mine soil and its affects on bioaccumulation of metals in tree species: Case study from a large opencast coalmining project. International Journal of Mining, Reclamation and Environment, 20(2), 96–110.

Manero, A., Kragt, M., Standish, R., & Miller, B. (2020). A framework for developing completion criteria for mine closure and rehabilitation. Journal of Environmental Management, 273(1), 111078.

Marais, L. (2013). The impact of mine downscaling on the Free State Goldfields. Urban Forum, 24(4), 503–521. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12132-013-9191-3

Marais, L. (2023). The social impacts of mine closure in south africa: housing policy and place attachment. Routledge.

Marais, L., Ndaguba, M., Mmbadi, E., Cloete, J., & Lenka, M. (2022). Mine closure, social disruption and crime in South Africa. The Geographical Journal, 188(3), 383–400.

Morrison-Saunders, A., McHenry, P., Sequeira, R., Gorey, P., Mtegha, H., & Doepel, D. (2016). Integrating mine closure planning with environmental impact assessment: Challenges and opportunities drawn from African and Australian practice. Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal, 34(2), 117–128.

Neil, C., Tykkylainen, M., & Bradbury, J. (1992). Coping with closure: An international comparison of mine town experiences. Routledge.

O’Connor, C., & Ruddell, P. (2021). After the downturn: Perceptions of crime and policing. The Canadian Geographer, 65(3), 281–291. https://doi.org/10.1111/cag.12671

Orduña-Malea, E., & López-Cózar, E. (2018). Dimensions: Re-discovering the ecosystem of scientific information. El Profesional De La Información, 27(2), 430–431. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2018.mar.21

Pactwa, K., Konieczna-Fuławka, M., Fulawka, K., Aro, P., Jaśkiewicz-Proć, I., & Kozłowska-Woszczycka, A. (2021). second life of post-mining infrastructure in light of the circular economy and sustainable development: Recent advances and perspectives. Energies, 14(22), 7551.

Peck, P., & Sinding, K. (2009). Financial assurance and mine closure: Stakeholder expectations and effects on operating decisions. Resources Policy, 34(4), 227–233.

Pritchard, A. (1969). Statistical bibliography or bibliometrics? Journal of Documentation, 25(4), 348–349.

Sahel, J. (2011). Quality versus quantity: Assessing individual research performance. Science Translational Medicine, 84(3), 84. https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.300224

Sahoo, S., Maiti, D., & Sahu, N. (2016). Citation Study of Advances in Anthropology. Journal of Library & Information Science, 6(1), 82–103.

Sengupta, N. (1993). Environmental impacts of mining. Monitoring, restoration and control. Lewis Publishers.

Sharma, S., & Lenka, U. (2022). Counterintuitive, yet essential: Taking stock of organizational unlearning research through a scientometric analysis (1976–2019). Knowledge Management Research & Practice, 20(1), 152–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/14778238.2021.1943553

Sin, H., Tan, L., & McPherson, G. (2022). A PRISMA review of expectancy-value theory in music contexts. Psychology of Music, 50(3), 976–992. https://doi.org/10.1177/03057356211024344

Sobolewski, A., & Sobolewski, N. (2022). Holistic design of wetlands for nine water treatment and biodiversity: A Case Study. Mine Water and the Environment, 41, 292–299.

Stacey, J., Naude, A., Hermanus, M., & Frankel, P. (2010). The socio-economic aspects of mine closure and sustainable development: Literature overview and lessons for the socio-economic aspects of closure: Report 1. The Journal of the Southern African Institute of Mining and Metallurgy, 110(July), 379–394.

Svobodova, K., Owen, J., Kemp, D., Moudry, V., Lebre, E., Stringer, M., & Sovacool, B. (2022). Decarbonization, population disruption and resource inventories in the global energy transition. Nature Communications. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-35391-2

Tiemann, C., Young, R., & Dixon, K. (2022). Rehabilitation and mine closure policies creating a pathway to relinquishment: An Australian perspective. Restoration Ecology, 30(1), e13785.

Van Asche, K., Deacon, L., Gruezmacher, M., Summers, R., Lavoie, S., Jones, K., & Parkins, J. (2017). Boom and bust: Local strategies for big events. Groningen: In Planning. http://hdl.handle.net/10419/158000.

Van Assche, K., Gruezmacher, M., & Deacon, L. (2020). Land use tools for tempering boom and bust: Strategy and capacity building. Land Use Policy, 93, 103994. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2019.05.013

Van Dalen, H. (2021). How the publish-or-perish principle divides a science: The case of economists. Scientometrics, 126, 1675–1694. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-020-03786-x

Vivoda, V., Kemp, D., & Owen, J. (2019). Regulating the social aspects of mine closure in three Australian states. Journal of Energy & Natural Resources Law, 37(4), 405–424. https://doi.org/10.1080/02646811.2019.1608030

Wang, X., & Lo, L. (2021). Just transition: A conceptual framework. Energy Research & Social Science, 82, 102291.

Watson, A., & Olalde, M. (2019). The state of mine closure in South Africa: What the numbers say. Journal of the Southern African Institute of Mining and Metallurgy, 111, 639–645.

World Bank. (2002). It’s not over when it’s over: Mine closure around the world. World Bank Group’s Mining Department, Global Mining.

Zalesky, J., & Capova, K. (2017). Monitoring and assessment of remedial measures in closed open cast mine. In M. Mikoš, Ž Arbanas, Y. Yin, & K. Sassa (Eds.), Advancing culture of living with landslides. WLF 2017. Springer.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of the Free State. Open access funding provided by University of the Free State.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ndaguba, E., Marais, L. A scientometric analysis of mine closure research. Environ Dev Sustain (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-023-03785-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-023-03785-x