Abstract

Indonesia’s severely flawed centralized wastewater treatment system has caused economic and socioeconomic losses for decades. An alternative system has been called for under a national-scale program called Sanimas or Community-Led Total Sanitation (CLTS), which would cater to 50–100 urban families in every intervention with urgent needs through the operation of a decentralized wastewater treatment system. Through household participation, this program features a co-production system wherein the national-level government initiates and provides initial funding until construction, after which a community-appointed social organization takes over. This study implemented a multicriteria approach to assess sustainability in Sanimas communities in Jakarta: 67 in Menteng (Central Jakarta) and At-Taubah in Koja (North Jakarta). Connected households and facility-operating committees were questioned separately for their opinions on six aspects that explained the survival of the establishment of a facility: technical, management, community participation, financial, institutional, and environmental. We found that although the facility’s excellence and overall satisfaction with the program were unanimous, Koja and Menteng showed substantial differences in management, institutional, and financial aspects, largely due to administrative policies, payment contributions, and committee commitments. Interviews revealed that periodic testing of the treated water was neglected, against the provided guidance. In conclusion, communities have come to focus more on the technical functionalities of the installation, regardless of the state of the management, which is indisputable not only in Menteng but also in Koja. Finally, we argue that although decentralized systems can substitute centralized systems, they still require stringent and adequate support in quality control and troubleshooting.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Poor sanitation has many effects, from a wider prevalence of contagious diseases to stunting of children’s growth (Odagiri et al., 2020), school dropout among adolescent girls (Vijay Panchang, 2021), economic losses, and substandard responses to global pandemics (Sanitation & Water for All, 2020). According to an article published in 2020 by the World Bank, which characterized Jakarta as a city without sewerage because only 2% of wastewater is properly treated before disposal, Indonesia continues to struggle to improve its sanitation quality (ARCOWA, 2018; Prevost et al., 2020; Widyarani et al., 2022). Wastewater management in Indonesia is severely flawed for municipal facilities (centralized system), which has been an impediment at a capacity of 0,301 km3/year since 2008 (Food & Agriculture Organizations, 2022). The Sewerage Masterplan of Jakarta (under Jakarta Governor Regulation Number 41/2016) targets approximately 80% coverage by 2050 by adding 14 additional installations across all municipalities (JICA, 2012). While this ambitious plan exhibits its own risks and challenges (Murwendah et al., 2020; Prevost et al., 2020; Winters et al., 2014), the management system requires a more stringent strategy than building physical installations (Hashimoto, 2019). Furthermore, many sources indicate that residential septic tanks are loosely supervised and enforced, particularly in poor neighborhoods, despite regulations stating otherwise (Cahyadi et al., 2021); and often, they leak or improperly dislodge feces and wastewater directly into the closest waterbody (Widyarani et al., 2022; Widyatmi Putri, 2019). Nationally, septage services are not conducive; however, general ignorance among the public regarding the long-term effects of poor sanitation exists (Winters et al., 2014).

To combat this problem, the Government of Indonesia enforces the Regulation of Indonesia Health Ministry Number 3/2014 about Community-Led Total Sanitation (CLTS) and educates the people of Indonesian through a campaign about the importance of hygiene practices and environmental health. It highlights the five pillars of CLTS that emphasize the channeling of wastewater pipes to infiltrate wells/centralized systems/sewers, separating the waste from the kitchen and bath from that of the toilet, and enabling regular maintenance. The principles of CLTS were spread through sanitation-related programs. SanimasFootnote 1 (Community-Based Sanitation) is a part of the CLTS vision focusing on dirty water, which began to be implemented in 2008 (Smets, 2015). It is a community-based sanitation program that uses a Decentralized Wastewater Treatment System (DEWATS) to reach 50–100 families for every intervention in dense urban areas in Indonesia (Tarlani et al., 2021). Bremen Overseas Research and Development Association (BORDA) initiated DEWATS as an approach to treat domestic wastewater with flexibility, low cost, and low maintenance, making it accessible to poor households, especially in developing countries (Center for Advanced Philippine Studies (CAPS), 2011; Hassib & Noor, 2015). Sanimas prides itself as a demand-driven approach program (Roma & Jeffrey, 2010) where Ministry of Public Works and Housing (MPWH) encourages regents/mayors to assign themselves by submitting a letter stating they are willing to improve their sanitation condition (Fig. 1) indicating that local governments and, by extension, their constituencies are ready to maintain the facility for a long time, particularly in effluent quality testing whose absence is a substantial concern according to our findings.

Sanimas implementation process. Source: (Ministry of Public Works & Housing, 2016)

By reviewing numerous studies, we believe that a decentralized system is a cost-effective and environmentally reliable alternative. To fill the gap in sufficient infrastructure, decentralized system promotes environmental sustainability by restoring resource quality (Muzioreva et al., 2022); reduces carbon footprint; is financially benefitting (Arias et al., 2020); and, in the context of community-led facility, gives a platform to people to exercise their rights to politics and decision-making (Cahyadi, 2021). In addition, topography may limit centralized systems from reaching higher-level areas, thereby imposing risks of inequality between neighborhoods whose access is feasible and not feasible. However, we also recognize some potential challenges of this type of service. The Ministry’s unpublished data and Sanimas-related website revealed that of the IDB-funded (Islamic Development Bank) locations built around 2014–2019, 4% stopped operating, while 96% are in operation (Ministry of Public Works & Housing, 2021).

A subject of concern that shadows the longevity of community-led facilities is the efficacy of its management to support its long-term operation, including raising enough money and realizing adequate benefits to keep the community-based institution intact. Moreover, technology selection affects the flexibility of the system and ultimately influences the community’s commitment to prolonged running. In the case of Sanimas, DEWATS serves as a feasible and easy-to-run system; however, in some cases, a pump is installed to alleviate the load from or to the main compartment, increasing the maintenance effort (electricity bill and pump replacement). Finally, the additional burden felt among community members to manage a facility that is supposed to be provided by the public sector may factor in their hesitation to support it (Beard, 2019; Li et al., 2019).

We studied two CLTS implementations in Jakarta to provide examples of communities that have been successfully operating for over five years. They also provide examples of their triumph over system limitations. Perhaps this lesson can lead to better design programs and policies to improve community-led decentralized systems. To do so, we decided to use a multi-element framework of sustainability often applied in community programs. There have been few sustainability-related studies regarding community-based wastewater programs; however, location-wise Indonesia’s context is scarce. Most community-focused sustainability studies have been conducted in rural Africa (Githinji, 2019; Ibrahim, 2017; Kilonzo & George, 2017; Peter & Nkambule, 2012; Senbeta & Shu, 2019; Whittington et al., 2009). Moreover, they fall into water supply category (Panthi & Bhattarai, 2008; Whaley & Cleaver, 2017), albeit sometimes along with sanitation as an addition to the context of the behavioral change target of the program, emphasizing handwashing habits, or the construction of an individual toilet (USAID & Rotary, 2013). Furthermore, studies of Sanimas have been repeatedly performed using approaches other than the multi-criteria approach (Roma & Jeffrey, 2010). Most of these studies used a qualitative approach (Dwipayanti & Indrawati, 2009; Suhaeniti, 2012), while some used observations (Hafidh et al., 2016) or combined methods (CWIS TA-Hub, 2021).

This study aimed to evaluate the sustainability of wastewater treatment facilities in two Sanimas locations in Jakarta. Using a framework of six permanence aspects, which include technical, management, community participation, financial, institutional, and environmental aspects, we divide the data collection into interviews with facility-operating committees (hereafter committees) and questionnaires distributed to connected households (also known as households). The findings contribute to the research community in two ways. First, a multi-criteria approach using primary data in a community-led decentralized system in a wastewater facility in an urban population of Indonesia is rare because centralized services are preferred. The interacting parameters can be observed through the chi-square results. For example, the expression of continuous support is positively related to the perception of environmental benefits and facility longevity. Second, it advocates the use of a decentralized system to fill the gap in sanitation management in urban settings by presenting two successful beneficiary groups in a community-based program.

2 Methodology

Despite the differences in spatial context and service type, parameters and indicators are still relevant for application in this study. In addition to the introduction of Sanimas communities and processing tools, a correlation diagram illustrates the hypothetical linkage between indicators, based on a literature study.

2.1 Assessment framework

The main challenge in creating the framework was the lack of parameters focusing on community-based wastewater programs, despite the large number of sanitation-related studies conducted previously, as most of them emphasized water resources. Therefore, the fitness of the variables for sanitation was examined beforehand.

This study used multi-criteria decision-making to collect variables to create a holistic evaluation of a program (Ibrahim, 2017; Panthi & Bhattarai, 2008). The framework (Table 1) included seven factors and 36 indicators used to understand the complexity of the wastewater user community. In the questionnaire, we also divided the questions targeted to the committee from those to connected households for reliability purposes.

The technical criterion covered facility performance that involved both parties: the committee for the main facility and households for the individual connection. The committee plays a pivotal role in managing operations. The management aspect was intended to respond to households’ opinions of the committee’s performance, such as its existence and clear definition of roles and duties, including operation, maintenance, financial reporting, educational and health campaigns, and holding regular meetings with connected households (Senbeta & Shu, 2019), as well as sanitation education (Ministry of Public Works & Housing, 2015).

For community participation, households were asked about their involvement in the program’s main events. For their part in facility maintenance, the survey investigated the following: bathrooms, grease traps, and control tubes. Women’s participation in the committee was examined in the institutional section (Ministry of Public Works & Housing, 2015; Senbeta & Shu, 2019). Committee members were asked about their organizational structure and establishment process. Cooperation with external agencies is also considered important.

The questions in the financial section were mostly directed at facility-operating committee members as financial agents, and households provided responses concerning their diligence in paying the tariff. The following section is related to the environment and sustainability, which targeted the awareness of the watershed management plan in their area and their confidence in the Sanimas system to not pollute the clean water resources in the given area. The committee was asked about periodic laboratory checks and environmental measures incorporated during construction and until the present (McConville & Mihelcic, 2007; Ministry of Public Works & Housing, 2015). The final questions investigated household loyalty and overall satisfaction with the programme.

2.2 Correlation hypothesis

Overall, 20 correlations were tested using the chi-square test for association (Fig. 2). Sustainability correlation was tested using the six remaining variables.

Some variables that may exhibit interrelationships were also tested, such as facility management to aspects of technical, financial, and community participation and financial participation to institutional satisfaction and physical performance, as well as some background-related items.

2.3 Location selection and data collection

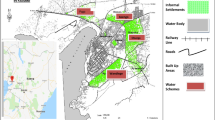

When looking at the study locations, we considered their representation of the system application and communication accessibility. As a precondition for Sanimas beneficiaries, they are on the list of urgently needed sanitation intervention locations (Jakarta Statistical Agency, 2019). As Figs. 3 and 4 illustrate, KPP 67 is adjacent to the Ciliwung River across the Manggarai Bus Terminal (a big class terminal hub). The KPP At-Taubah is three kilometers from Jakarta Bay and Tanjung Priok Harbor (one of the most important harbors in Jakarta), and thus, it is close to many warehouses. Both occupied small areas with high population densities and were in high proximity to major access roads or hub terminals/railway stations with limited access to adequate drainage and solid and wastewater systems, posing health risks and hazards (Rukmana, 2018).

Moreover, Menteng and Koja have been successfully conducting management for over five years, serving over 70 household members using a slightly different system design configuration. The At-Taubah system featured a pump owing to topographical challenges that might hinder the access of the centralized system to this area. Even if it reaches this area, it is highly possible for this community to continue operating a localized system supported by pumps. This study anticipated a pump-induced system and accounted for the additional financial burden that the Sanimas community would face in paying for electricity, troubleshooting, and replacement. These characteristics represent the biggest challenge in completing centralized access and, simultaneously, the biggest potential for its alternatives.

The MPWH provided the latest updates on operating status in all locations nationally. In Jakarta, three communities were favored because of their coverage size, contact availability, and operating status. Unfortunately, Tegal Alur (West Jakarta) was unable to cooperate with the survey because of the ongoing local lockdown in the area. Thus, the evaluation involved two locations: KPP 67 in Central Jakarta and KPP At-Taubah in North Jakarta.

All distributed surveys were collected from the surveyed group at both locations, with all 40 items included in the questionnaire. Responses were given on a 5-point Likert scale (from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree) for all items, excluding background questions. Menteng and Koja collected 94 and 84 responses, respectively.

Full participation was obtained using a door-to-door one-time interview-based questionnaire, in which proxies assisted residents in answering and interpreting a questionnaire in Indonesia. The survey involved community members’ inventory and mapping using Google Earth-based maps. Remote interviews were conducted with key actors to collect authentic information and ensure participants’ willingness to cooperate.

On average, the interviews took 90 min and were conducted using a previously structured question list, following the framework provided in Table 1. The interviews were recorded with the permission of the Rukun Tetangga (RT)Footnote 2 chief, who holds a double role with the head of the committee. While Menteng’s acting chief has been involved as the leader of the system since the construction phase, Koja changed after the construction was completed. Hence, the interviews were conducted with the former leader.

2.4 Data processing

To test the dependency between ordinal variables in ordinal logistic regression, we adopted the chi-square test of association (Pearson’s chi-square) using the SPSS 26. This method is commonly used to evaluate the dependency of two variables regardless of their dependence. Furthermore, to examine the nature of the correlation between variables, this study used Kendall’s tau-b correlation coefficient (Tb) (Laerd Statistics, 2016).

The three datasets were divided based on location: (1) Menteng, (2) Koja, and (3) combined datasets. Each dataset was tested for all the 20 hypotheses. However, despite 100% resident participation, the initial chi-square test results were inadmissible because they violated the first assumption of the chi-square test; that is, more than 20% of cells exhibited fewer than five expected counts.

This was the largest challenge in this phase for all datasets because the target respondents were limited to Sanimas users, who had already reached their population headcount. To resolve this challenge, data regrouping was performed according to frequency to produce more conclusive results.Footnote 3 However, with regrouping, inconclusive operations remained because of the violation of expected count rules.

3 Results and findings

The survey results included neighborhood conditions, interview remarks, and questionnaire results, which were used to test the relationship between indicators. In some parts, the quantitative results were mixed with key actors’ descriptions to provide a better context or reasoning.

3.1 KPP 67, Menteng, Central Jakarta

KPP 67 is located on a river and railway, is densely populated, and is categorized as a slum. Administratively, it belongs to the Central Jakarta Municipality within the Menteng District and Menteng Subdistrict. Although the initiative started much later than when it was originally planned, this system has been treating wastewater from 94 households since 2017. Sanimas connects 76 houses and 94 households in the KPP 67, Menteng.

Despite its name, this location served three RTs (nos. 6, 7, and 8) with more than 31 houses (51 households) resident in RT 6, with the remaining 39 belonging to RT 7 and RT 8. At RT 6, several multi-family houses were found: nine dwellings with two households each, three with three households each, and one dwelling with four households. Questionnaires were given to all households living in the same buildings, but we found more subscribers than those recorded by MPWH (There were 94 connected households instead of 90, as observed in Table 2). Most Betawi and Javanese worked outside their residential areas for an extended period.

Being sandwiched between a major access road and railway made this location noisy, especially for nearby houses. Some residents kept chickens in cages located close to or in front of their houses. These were often poorly maintained, and a strong odor was noticeable upon entering the area. The location exhibited a narrow asphalt access road, which narrowed further as the road entered the neighborhood.

The green lot in Fig. 4 represents the communal facility that processed wastewater from the members. A field survey showed that aside from the operating conditions, the vacant spot adjacent to it was simultaneously used for bike parking lots of nearby residents and planting areas.

Their piping used gravitation to flow all wastewater into a common facility. It was located near a dyke in the southern area of the community (Fig. 4). It features an anaerobic baffled reactor with a volume of approximately 90 m3.

3.2 KPP At-Taubah, Koja, North Jakarta

Koja, like Menteng and common to the urban community in Jakarta, is a densely populated neighborhood area. In At-Taubah community, about 57 houses were found where about 84 families lived (detail explanation in Table 2), with around 20 inhabited by more than one household, most of which involved rented rooms. At the center, at the mosque where the communal facility was located, a vacant lot was found for communal gathering and playground.

This neighborhood was located near Tanjong Priok (Jakarta’s largest harbor) and features many warehouses, factories, and cargo terminals around this neighborhood. As a result, many rental rooms were built in this neighborhood. Some residents were settlers working near accommodations, most likely factories, and jobs related to shipping.

The neighborhood’s main road condition was in good quality and wide enough to accommodate a car. Most houses parked their bicycles on the porch and the alleys had sufficient room for motorcycles to pass through easily. The buildings were mostly made of concrete and bricks, although the houses in Koja were surrounded by taller walls and had smaller gates than those in Menteng (Fig. 5). As it was near a national-scale road, the traffic in this neighborhood was quite high.

At-Taubah featured a definite committee structure, judging by its ability to find subscribers as opposed to other locations. All houses involved in Sanimas had stickers on their front doors or walls, making it easy to identify the target respondents. Renters also paid the committee for services they received within the designated time.

The equipment here, exhibiting a similar volume to Menteng’s (approximately 90 m3 with anaerobic baffled reactors), ran daily, and the operator was a member of the committee as well as the caretaker of the mosque, who was paid using the collected money and was responsible for communal maintenance. The topographical gaps entailed that some local people had to install individual septic tanks because they could not be supported by the program. This created idle capacity, knowing that this facility was larger than Menteng’s.

3.3 Findings

A combination of questionnaire results, interviews, and qualitative data was grouped based on aspect. The results will be used to explore the differences and similarities between the two locations.

3.3.1 Affordable system lacking individual maintenance

BORDA-DEWATS has two ends of facilities connected by a piping system: the communal facility (anaerobic baffled reactor) and household equipment (toilets, grease trap, and control tub) (Reuter, 2008). Despite many challenges, the committee was satisfied with the treatment system; for example, a temporary halt occurred in Menteng during the construction phase because of fund disbursement. Moreover, despite being cheaply operated (with gravitation), we found that breakage occurred every two months due to clogging in Menteng. Similarly, Koja replaces the pump annually in addition to the electricity cost.

Households’ responses generally did not clash with committees between the two locations. Except for Q3 (whether they feel their opinion has been considered in the system design, with 83% yes in Menteng and 50% yes in Koja), in which both locations positively responded, more in Menteng did not decide whether to agree with the direct output of the machine (odor, sound, and water quality). Although the two communities exhibited slightly different configurations (Koja operated with a pump, while Menteng operated with gravitation), most were satisfied with the technology.

Moreover, community participation is critical for maintaining facilities at the household end. A noticeably similar pattern was found for each participation-related question in both locations. Menteng and Koja responded negatively to the first question, except for bathroom cleaning (98% and 99% for Menteng and Koja, respectively).

Conversely, many agreed that the individual facility worked well, and only a few households were in favor of altering it. Overall, 27% of Menteng households were neutral about the affordability of spare parts (as opposed to 17% in Koja, while 39% and 34% agreed and highly agreed, respectively). Families earning less than 2 million rupiahs (Indonesian currency) were a larger share in Menteng (22%) than in Koja (14%), which may be a direct factor.

However, it should be noted that Koja’s side showed greater agreement than Menteng (25% over 6% in system design, 15% over 6% in need identification, and 14% over 1% in decision-making). More respondents in Koja understood Sanimas’ health benefits than Menteng (100% vs. 88%). Clearly, this result showed that despite several group discussions in which the government (represented by subdistrict officials), field facilitators, and local people (Fig. 1) took part, most respondents did not feel that they participated in the whole process. The committee chief said that to hear more opinions from locals, the respondents were divided into several smaller groups.

At present, the Menteng Chief mentioned that willingness to clean the facility had been decreasing, especially relative to the time when the program was established. They added that RTs sometimes called for voluntary money collection from households. The cleaning staff were hired per job, and they were sometimes paid money or food. Meanwhile, in Koja, the pump was installed in the mosque area (neighborhood center in Fig. 5) to provide electricity. Mosques are commonly cleaned in Indonesia.

3.3.2 Leadership plays a major part in continuity

The results of the management, institutional, and financial observations are likely the most evident. In management, the contrast can be found in the response of the majority in Menteng (around a value of 2, disagree) versus that in Koja (around 5, highly agree), as shown in Table 3. The majority of Menteng disagreed that the committee existed (99%), that its roles were clearly defined (99%), and that they strictly complied with their roles and functions (88% disagreed that they regularly cleaned, 72% were neutral about the quick response, 85% disagreed that the machine was used daily, and 100% disagreed that monthly payments were regularly picked up). In addition to the responses to the final questions regarding meetings and book reporting, the beneficiaries of Koja agreed that its committee had been fulfilling its designated role.

Almost all respondents in Menteng disagreed with all items involving institutions. Conversely, Koja was mostly neutral in committee representation (46%) but agreed on the democratically chosen committee members (80%) and their participation in selection (97%). The concepts of representation and democracy in Indonesia are not new, and these results support this sentiment. Moreover, as repeatedly stated about the connection between the committee and RT, the interviews revealed that most members are indeed involved as an RT body (particularly in Menteng). Therefore, the selection of committee members was most likely not held as guided, or households were comfortable with RT managing Sanimas.

As indicated in the interviews, committees from both locations were integrated into the RT. However, Menteng’s overwhelming negative results were perhaps rooted in their lack of participation in the maintenance area. The crucial proof of this was their absence in the fee payment (next section) and, overall, in community participation. Although the Menteng Chief also mentioned that the existence of a committee is simultaneous with RT, every Sanimas-related activity was the RT’s business. Therefore, it was possible that KPP 67, as a Sanimas manager, did not exist in respondents’ minds. Moreover, aside from the educational and health campaigns conducted through Puskesmas (Community Health Center), program-related activities were never conducted by the RT/committee in Menteng.

The crucial challenge in both locations was the underwhelming response of the residents to the replacement of committee members. No term limit exists for positions in the committee; however, members of the committee may express their willingness to step down and be replaced by someone else. However, as RT must be reduced after five years, it could be challenging to sustain Sanimas following leadership and organizational changes. In Menteng, the chief indicated that he would not pressure the next leaders to continue Sanimas operations if they were reluctant because of the large effort required for technical maintenance and the lack of direct financial gain (in terms of either salary or food), creating a problem in institutional sustainability.

3.3.3 Stringent membership policy thrives in challenging conditions

As with the institutions, the response pattern shown by Menteng and Koja was still evident in the financial sector. Menteng respondents mostly disagreed, unlike the Koja households. Almost all respondents in Menteng denied paying a fee, but in Koja, the opposite occurred (100% stated that they paid a fee).

Koja required regular funding to pay for electricity and maintain the long life of its pumps. Menteng’s leader failed to see the importance of payment in ensuring a household’s sense of ownership of the facility. Koja’s leader indicated that, while the mosque’s jamaah (Islamic worshippers’ community) was glad to spare some of their cash for the facility, they imposed a strict subscription system. Each family obtained a membership card and placed it on their doors, indicating that they were part of Sanimas and simultaneously informing the person in charge that they constituted a paying household. Each family paid 10,000 rupiahs monthly (1.6 USD), and wealthy members were encouraged to pay more for their poor neighbors.

Conversely, for a monthly payment, Menteng’s leader mentioned that due to the prevailing economic circumstances, he refrained from imposing a strict membership system, especially in terms of fee collection (initially, people were not interested in Sanimas for fear of the expense). He added that he paid for the periodic desludging of the container, and it was paid out of his own pocket, supplemented by a small amount of RT’s money. Each year, Menteng was required to pay 4 million rupiah for desludging alone. Moreover, owing to the narrow access road, local traffic disruptions occur every time the truck arrives.

3.3.4 Complicated asset ownership and neglected environmental responsibility

Before soliciting answers, the surveyor explained Q37, and the results suggested that Koja understood this point better than Menteng. However, interviews shared that the point regarding careless wastewater disposal was mentioned during the dissemination and program promotion. In Menteng, the majority expressed their unfamiliarity with watershed management (70%), although some expressed awareness (22% agree, 1% highly agree). Meanwhile, Koja’s majority showed otherwise (87% agreed and highly agreed to have watershed awareness).

The evaluation of treated wastewater was procured in laboratory testing, as stated in the guidebook (Ministry of Public Works & Housing, 2016) that the government of Jakarta Province was to hold that responsibility. Consultation with authorized personnel and committee members showed that this test was never carried out. However, interviews revealed that a private party tested the quality of Menteng in the laboratory and obtained good results. Nevertheless, as the project initiator (state government) granted local people permission for utilization, it left the provincial agency (Jakarta) with no legal rights or political power for technical or program evaluation.

Most respondents were certain that Sanimas would not pollute (99% in Menteng and 100% in Koja). All respondents in both locations agreed that they were satisfied with the program and would subscribe for a long time. In Menteng, some respondents indicated that if the facility continued its operations, it would continue to use the service. This shows that the technical factor is probably the most reliable factor for ensuring community loyalty to the program. Both Menteng and Koja’s leaders indicated that local people were thrilled with Sanimas because they were freed from the burden of maintaining the cost of individual septic tanks. They also noted that their neighborhoods were less inundated with water during heavy rain.

3.4 Factors correlation

Overall, each dataset presents different correlation results (Table 4). The environment aspect demonstrated positive and strongly coordinated sustainability across all datasets. Separately, the correlation of sustainability aspects in Menteng was significant with technical and management, while that in Koja was with community participation, management, and financial. Apart from management aspect correlation, the combined dataset had strong result with community participation and technical factors. Interconnected variable tests indicated that functional satisfaction and income were correlated with payment aspect in both locations. Other significant results were committee performance and technology satisfaction in Menteng, and community engagement and management aspects.

Finally, the combined results from both locations identified a relationship between management factor with three factors: technical, financial, and community participation, as well as a financial aspect correlation with institutional, technical, and income. Furthermore, aspects of environment and age were also correlated, as well as education and community participation.

4 Discussion

This study evaluated the sustainability of Menteng and Koja as community beneficiaries and long-term operators of the Sanimas. At its core, Sanimas falls under the state-led co-managed initiative, in which benefitted community operate and maintain a sewage system outside the centralized system. This program takes place in an urban context, which is considered amiss compared to the rural population, owing to its heterogonous and transient demographics with weak social cohesiveness (Birkinshaw et al., 2021; Li et al., 2019).

We also highlighted two problems. The first is regarding overreliance on communities because the willingness to pay for improved sanitation services was low even in the Java region (Yasin et al., 2020). Second is negligence in responsibilities demonstrated by state- and provincial-level governments in community-managed projects (Li et al., 2019; Whaley & Cleaver, 2017). This study stressed the potential environmental degradation, which was ironic for a project aiming to stop releasing hazardous pollutants to waterbodies (United Nations, 2015). However, there was also a gap in policy regarding the installation’s physical ownership, authorized agency for troubleshooting and support, and upscaling initiative, which hindered the dispatch of maintenance assistance, as reported in South Lampung, Indonesia (Chong et al., 2016).

The confusion of management authority in both locations (RT and committee being separated on guidelines but integrated) perhaps presented a blessing in disguise to protect the longevity of this project. As the leaders decided to keep or forsake the system operation (a threat to institutional sustainability), it could be suggested that RT should hold the authority to manage Sanimas. Given that RT is a social gathering that is membered by community members themselves, and simultaneously they choose their leader, this may clarify the complicated nature of program stewardship and increase the ownership of the system, which is known to be a major driver for sustaining community-led projects (Puskás et al., 2021; Shilpi Srivastava et al., 2019). Moreover, as Menteng demonstrated the significance of the role of the RT chief in program establishment, this may be a good solution to resolve institutional challenges in communities with weak participation and modalities (Khwaja, 2009). However, the project design may allow only half of the RT or even include different RT members to connect to the system owing to topography and capacity design.

Aside from leadership, an important lesson in Koja was a good management system through stringent membership rules and administration. Pump installation had been a blessing in disguise, as it settled the communal facility’s incorporation with the local mosque (also managed by the community). This seemed to be the correct path to ensure that it was well-maintained and well-supervised. Post-construction local participation, as demonstrated in regular payments in Koja, was an indication of ownership that households paid for the system’s endurance over the long term (Whaley & Cleaver, 2017).

The qualitative results did not necessarily reflect the chi-square results, whereas environment and management were constant variables correlated with sustainability. However, it may be worth noting the positive results in Koja. For technical duty, it is arguably correct to say that because the management committed to maintaining the pump, the facility ran every day. Hence, this finding reflects the ground conditions. Perhaps a comparison of the statistical results to the interview and paper results may identify the limitations of this study, particularly to the methodology. It is a common notion that chi-square depends heavily on sample size (McHugh, 2013).

Finally, this study attempts to introduce the well-suited examples of community-based decentralized systems. Keeping in mind the target of universal access and the decline in longevity prospects, we argued that this alternative succeeded even in a dynamic form of society. Although there was skepticism about whether decentralized systems served as an accomplished alternative to centralized systems in big cities (Dorji et al., 2019), the community could run their own wastewater treatment scheme. Nevertheless, we would like to mention the practice of involuntary resettlements in the name of an urban improvement program that further extends the disparity gap between urban communities, which is against the target of decentralized systems (Sapkota & Ferguson, 2017; Sholihah & Chen, 2020). Evidently, no such practice was noted at either location.

5 Conclusions and future research

This study analyzed the continuity of Sanimas as a community-led sanitation program that is rarely approached using multifaceted aspects. We found that, although participation had been practiced and encouraged in an urban context (Brazeau-Béliveau & Cloutier, 2021; Puskás et al., 2021), community-managed wastewater service challenges began with the readiness of local communities to carry an important task. Without support from authorized government and practicing agencies (NGO, NPO, universities, and others), the challenge did not only stop at generating participation in the problem identification level, but also motivated their willingness to contribute to the system maintenance for a long time, which includes paying, cleaning, and ensuring the safety of the environment. The sustainability of the program should not be evaluated solely by machinery operation but also by management and community participation (Birkinshaw et al., 2021; Roma & Jeffrey, 2010; Whaley & Cleaver, 2017).

The authors recognize that the results are context-based and should be interpreted as such. However, other communities will be able to learn from these cases because of the uniform project design. We recommend a more objective approach in future studies because of the risk of self-evaluation. We advise that the committee be formally integrated with RT to allow leaders to take Sanimas’s continuity responsibility more seriously. Moreover, integrating it with RT or a higher level of administrative border (sub-district) will develop an apparent status/identity, especially when troubleshooting requires higher-level government support. MPWH urgently needs to provide a better scheme of division of responsibility through discussion, confirmation, and legalization with the local government, NGOs, and possibly private organizations for Sanimas’ maintenance, particularly concerning wastewater quality testing.

Data availability

The directory of IDB-funded Sanimas locations provided by MPWH is not publicly available for reasons undisclosed to the authors. Meanwhile, the datasets containing the questionnaire results are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Notes

In attempt to continue pursuing 100% sanitation access, Indonesia abides to expand CLTS-related programs, Pamsimas and Sanimas are some that utilize community participation, focusing on behavioral change and facility construction (Pamsimas: water point, Sanimas: wastewater treatment installation) (Pham et al., 2014).

The RT or Rukun Tetangga is the smallest administrative unit in Indonesia (after household), wherein several of them account for 1 RW or rukun warga. It is the terminology used for both villages (desa) and sub-districts (kelurahan). In Indonesia, several villages/sub-districts make up one district (kecamatan). An RT is led by a chief and its body (consists of treasurer, secretary, some divisions), and so is an RW.

The original scaling was regrouped by into 2: agree (4: agree and 5: highly agree) and disagree (1: highly disagree, 2: disagree, and 3: neutral). Despite this attempt, there are still homogeneity found in the answers that ten marked with gray highlight in the final result.

References

ARCOWA. (2018). Wastewater management and resource recovery (p. 56). Gef, UNDP, PEMSEA. http://seaknowledgebank.net/sites/default/files/wastewater_management_and_resource_recovery_in_Indonesia_1.pdf.

Arias, A., Rama, M., González-García, S., Feijoo, G., & Moreira, M. T. (2020). Environmental analysis of servicing centralised and decentralised wastewater treatment for population living in neighbourhoods. Journal of Water Process Engineering, 37, 101469. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwpe.2020.101469

Beard, V. A. (2019). Community-based planning, collective action and the challenges of confronting urban poverty in Southeast Asia. Environment and Urbanization, 31(2), 575–596. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956247818804453

Birkinshaw, M., Grieser, A., & Tan, J. (2021). How does community-managed infrastructure scale up from rural to urban? An example of co-production in community water projects in Northern Pakistan. Environment and Urbanization, 33(2), 496–518. https://doi.org/10.1177/09562478211034853

Brazeau-Béliveau, N., & Cloutier, G. (2021). Citizen participation at the micro-community level: The case of the green alley projects in Quebec City. Cities, 112, 103065. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2020.103065

Cahyadi, R., Kusumaningrum, D., & Abdurrahim, A. Y. (2021). Community-based sanitation as a complementary strategy for the Jakarta Sewerage Development Project: What can we do better? E3S Web of Conferences, 249, 01003. https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202124901003

Center for Advanced Philippine Studies (CAPS). (2011). Eight case studies about sustainable sanitation projects in Cambodia. Center for Advanced Philippine Studies (CAPS). https://www.susana.org/en/knowledge-hub/resources-and-publications/library/details/1327.

Chong, J., Abeysuriya, K., Hidayat, L., Sulistio, H., & Willetts, J. (2016). Strengthening local governance arrangements for sanitation: Case studies of small Cities in Indonesia. Aquatic Procedia, 6, 64–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aqpro.2016.06.008

CWIS TA-Hub. (2021). Independent evaluation of Sanimas model as an approach for providing decentralized sanitation [Independent Evaluation]. Citywide Inclusive Sanitation Technical Assistance Hub for South Asia. https://www.isdb.org/sites/default/files/media/documents/2021-03/SANIMAS%20Model_as%20an%20Approach%20for%20Prodiving%20Decentralised%20Sanitation_March%202021.pdf.

Domínguez, O.-O., & Hurtado, B. (2019). Assessing sustainability in rural water supply systems in developing countries using a novel tool based on multi-criteria analysis. Sustainability, 11(19), 5363. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11195363

Dorji, U., Tenzin, U. M., Dorji, P., Wangchuk, U., Tshering, G., Dorji, C., Shon, H., Nyarko, K. B., & Phuntsho, S. (2019). Wastewater management in urban Bhutan: Assessing the current practices and challenges. Process Safety and Environmental Protection, 132, 82–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psep.2019.09.023

Dwipayanti, N. M. U., & Indrawati, K. (2009). Perception of Sanimas user community and sanimas program facilitator on the implementation of sanimas program in Denpasar. Sustainable Infrastructure and Built Environment in Developing Countries. The 1st International Conference on Sustainable Infrastructure and Built Environment in Developing Countries, Bandung, Indonesia. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228436251_Perception_of_Sanimas_User_Community_and_Sanimas_Program_Facilitator_on_The_Implementation_of_Sanimas_Program_in_Denpasar.

Food and Agriculture Organizations. (2022). AQUASTAT [Statistical Data]. https://www.fao.org/aquastat/statistics/query/results.html.

Githinji, S. N. (2019). Factors influencing sustainability of community-based water projects In Kajiado County, Kenya: A case of Kajiado Central Sub-county [Master Thesis, University of Nairobi]. http://erepository.uonbi.ac.ke/handle/11295/152862.

Hafidh, R., Kartika, F., & Farahdiba, A. U. (2016). Keberlanjutan Instalasi Pengolahan Air Limbah Domestik (Ipal) Berbasis Masyarakat, Gunung Kidul Yogyakarta. Jurnal Sains & Teknologi Lingkungan, 8(1), 46–55. https://doi.org/10.20885/jstl.vol8.iss1.art5

Hashimoto, K. (2019). Institutional mechanisms for sustainable sanitation: Lessons from Japan for Other Asian Countries. Asian Development Bank, 1001. https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/524116/adbi-wp1001.pdf.

Hassib, Y., & Noor, M. (2015). Recommendations concerning the scaling-up- potential of BORDA-DEWATS wastewater treatment in the urban context of Kabul, Afghanistan. Susana.org. https://www.susana.org/en/knowledge-hub/resources-and-publications/library/details/3396?pgrid=1.

Ibrahim, S. H. (2017). Sustainability assessment and identification of determinants in community-based water supply projects using partial least squares path model. Journal of Sustainable Development of Energy Water and Environment Systems, 5(3), 345–358. https://doi.org/10.13044/j.sdewes.d5.0153

Jakarta Statistical Agency. (2019). Data RW Kumuh di Wilayah Kota Administrasi Jakarta Pusat Tahun 2018. Jakarta Open Data. https://data.jakarta.go.id/dataset/data-rw-kumuh-di-wilayah-kota-administrasi-jakarta-pusat-tahun-2018.

JICA. (2012). Bagian D - Perumusan Master Plan Proyek Untuk Pengembangan Kapasitas Sektor Air Limbah Melalui Peninjauan Master Plan Pengelolaan Air Limbah di DKI Jakarta di Republik Indonesia. JICA. https://openjicareport.jica.go.jp/pdf/1000005122_01.pdf.

Khwaja, A. I. (2009). Can good projects succeed in bad communities? Journal of Public Economics, 93(7–8), 899–916. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2009.02.010

Kilonzo, R., & George, V. (2017). Sustainability of community based water projects: Dynamics of actors’ power relations. Journal of Sustainable Development, 10(6), 79–86. https://doi.org/10.5539/jsd.v10n6p79

Laerd Statistics. (2016). Kendall’s Tau-b using SPSS Statistics. Laerd Statistics Website. https://statistics.laerd.com/spss-tutorials/kendalls-tau-b-using-spss-statistics.php

Li, B., Hu, B., Liu, T., & Fang, L. (2019). Can co-production be state-led? Policy pilots in four Chinese cities. Environment and Urbanization, 31(1), 249–266. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956247818797276

McConville, J. R. (2008). Assessing sustainable approaches to sanitation planning and implementation in West Africa [Licentiate Thesis, Mark- och vattenteknik, Land and Water Resource Engineering, Kungliga Tekniska högskolan]. http://kth.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:13840/FULLTEXT01.pdf.

McConville, J. R., & Mihelcic, J. R. (2007). Adapting life-cycle thinking tools to evaluate project sustainability in international water and sanitation development work. Environmental Engineering Science, 24(7), 937–948. https://doi.org/10.1089/ees.2006.0225

McHugh, M. L. (2013). The Chi-square test of independence. Biochemia Medica, 2, 143–149.

Ministry of Public Works and Housing. (2015). Book 4—Operation and Maintenance of Sanimas IBD. Ministry of Public Works and Housing. https://ciptakarya.pu.go.id/setditjen/kkntematik/category/modul

Ministry of Public Works and Housing. (2016). Petunjuk Teknis Sanimas IDB (Technical Guidance of IDB-funded Sanimas). Government of Indonesia, Ministry of Public Works and Housing. http://ciptakarya.pu.go.id/setditjen/kkntematik/id/buku-petunjuk-teknis-sanimas-idb

Ministry of Public Works and Housing, D. of S. (2021). Ministry of Public Works and Housing, Sanitation Directorate Web Portal. Ministry of Public Works and Housing Website. http://plpbm.pu.go.id/v2/

Murwendah, I., Rosdiana, H., & Filberto Sardjono, S. L. (2020). The challenges of providing safe sanitation as a public good in DKI Jakarta. Web of Conference, 211, 01022.

Muzioreva, H., Gumbo, T., Kavishe, N., Moyo, T., & Musonda, I. (2022). Decentralized wastewater system practices in developing countries: A systematic review. Utilities Policy, 79, 101442.

Odagiri, M., Cronin, A. A., Thomas, A., Afrianto, M., Zainal, M., Setiabudi, W., Emerson, M., Badloe, C., Dewi, T., Agus, I., Wahanudin, L., Mardikanto, A., & Pronyk, P. (2020). International journal of hygiene and environmental health achieving the sustainable development goals for water and sanitation in Indonesia – Results from a five-year (2013–2017) large-scale effectiveness evaluation. International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health, 230, 113584.

Panthi, K., & Bhattarai, S. (2008). A Framework to Assess Sustainability of Community-based Water Projects Using Multi-Criteria Analysis. Advancing and Integrating Construction Education, Research & Practice, 464–472. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/247935206_A_Framework_to_Assess_Sustainability_of_Community-based_Water_Projects_Using_Multi-Criteria_Analysis

Peter, G., & Nkambule, S. E. (2012). Factors affecting sustainability of rural water schemes in Swaziland. Physics and Chemistry of the Earth, Parts a/b/c, 50–52, 196–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pce.2012.09.011

Pham, N. B., Kuyama, T., & Kataoka, Y. (2014). COMMUNITY-BASED SANITATION LESSONS LEARNED FROM SANIMAS PROGRAMME IN INDONESIA. Water Environment Partnership in Asia. https://www.iges.or.jp/en/pub/community-based-sanitation-lessons-learnt/en

Prevost, C., Thapa, D., & Roberts, M. (2020). Cities without sewers—Solving Indonesia’s wastewater crisis to realize its urbanization potential [Organization]. World Bank Blogs. https://blogs.worldbank.org/eastasiapacific/cities-without-sewers-solving-indonesias-wastewater-crisis-realize-its-urbanization

Puskás, N., Abunnasr, Y., & Naalbandian, S. (2021). Assessing deeper levels of participation in nature-based solutions in urban landscapes – A literature review of real-world cases. Landscape and Urban Planning, 210, 104065.

Reuter, S. (2008). BORDA_Lessons learnt from a national community based sanitation program.pdf. Bremen Overseas Research and Development Association (BORDA). https://www.bgr.bund.de/EN/Themen/Wasser/Veranstaltungen/symp_sanitat-gwprotect/present_reuter_pdf.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=2

Roma, E., & Jeffrey, P. (2010). Evaluation of community participation in the implementation of community-based sanitation systems: A case study from Indonesia. Water Science and Technology, 62(5), 1028–1036. https://doi.org/10.2166/wst.2010.344

Rukmana, D. (2018). Upgrading housing settlement for the urban poor in Indonesia: An analysis of the Kampung Deret program. In B. Grant, C. Y. Liu, & L. Ye (Eds.), Metropolitan Governance in Asia and the Pacific Rim (pp. 75–94). Singapore: Springer.

Sanitation and Water for All. (2020). Republic of Indonesia Country Overview (Asia and The Pacific Finance Ministers’ Meeting). Sanitation and Water for All. https://www.sanitationandwaterforall.org/sites/default/files/2020-12/2020_Country%20Overview_Indonesia.pdf

Sapkota, N., & Ferguson, S. (2017). Involuntary Resettlement and Sustainable Development: Conceptual Framework, Reservoir Resettlement Policies, and Experience of the Yudongxia Reservoir. Asian Development Bank. https://doi.org/10.22617/WPS178903-2

Senbeta, F., & Shu, Y. (2019). Project implementation management modalities and their implications on sustainability of water services in rural areas in Ethiopia: Are community-managed projects more effective? Sustainability, 11(6), 1675. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11061675

Shilpi Srivastava, M. L., & Kar, K. (2019). Makin “Shit” everybody’s business. Co-Production in Urban Sanitation. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.30069.42723

Sholihah, P. I., & Chen, S. (2020). Improving living conditions of displacees: A review of the evidence benefit sharing scheme for development induced displacement and resettlement (DIDR) in urban Jakarta Indonesia. World Development Perspectives, 20, 100235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wdp.2020.100235

Smets, S. (2015). Water supply and sanitation in Indonesia: Turning finance into services for the future (Working Paper No. 100891; p. 76). World Bank Group. https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/326971467995102174/watersupply-and-sanitation-in-indonesia-turning-finance-into-services-for-the-future

Suhaeniti, S. (2012). Wastewater management in Indonesia: Lessons learned from a community-based sanitation programme. SUSTAINABLE WATER AND SANITATION SERVICES FOR ALL IN A FAST CHANGING WORLD, 1–6. https://repository.lboro.ac.uk/articles/conference_contribution/Wastewater_management_in_Indonesia_Lessons_learned_from_a_community_based_sanitation_programme/9596105.

Tarlani Damayanti, V., & Ekasari, A. M. (2021). Integrative solutions for the acceleration of open defecation free (ODF) in Bandung City. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 830(1), 012086. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/830/1/012086

United Nations. (2015). SDGs Goal 6: Ensure access to water and sanitation for all [Official]. Sustainable Development Goals. https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/water-and-sanitation/.

USAID and Rotary. (2013). WASH Sustainability Index Tool (Complete Version) [English]. WASHplus. http://washplus.org/rotary-usaid.html.

Vijay Panchang, S. (2021). Beyond toilet decisions: Tracing sanitation journeys among women in informal housing in India. Geoforum, 124(May), 10–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2021.05.011

Whaley, L., & Cleaver, F. (2017). Can ‘functionality’ save the community management model of rural water supply? Water Resources and Rural Development, 9, 56–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wrr.2017.04.001

Whittington, D., Davis, J., Prokopy, L., Komives, K., Thorsten, R., Lukacs, H., Bakalian, A., & Wakeman, W. (2009). How well is the demand-driven, community management model for rural water supply systems doing? Evidence from Bolivia Peru and Ghana. Water Policy, 11(6), 696–718. https://doi.org/10.2166/wp.2009.310

Widyarani Wulan, D. R., Hamidah, U., Komarulzaman, A., Rosmalina, R. T., & Sintawardani, N. (2022). Domestic wastewater in Indonesia: Generation, characteristics and treatment. Environmental Science and Pollution Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-022-19057-6

Widyatmi Putri, P. (2019). The forgotten water – The role of decentralised wastewater management in Jakarta’s Socio-Ecological System. Urbanet. Info. https://www.urbanet.info/wastewater-management-in-jakarta/

Winters, M. S., Karim, A. G., & Martawardaya, B. (2014). Public service provision under conditions of insufficient citizen demand: Insights from the urban sanitation sector in Indonesia. World Development, 60, 31–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.03.017

Yasin, M. Z., Shahab, H. A., Nuryitmawan, T. R., & Arini, H. R. B. (2020). Willingness to pay for improved sanitation in Indonesia: cross- sectional difference-in-differences (MPRA Paper No. 105070; Munich Personal RePEc Archive, p. 22). Research Institute of Socio-Economic Development (RISED); Munich Personal RePEc Archive. https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/105070/.

Acknowledgements

We highly regard the Sanimas communities of KPP 67 and KPP At-Taubah for their cooperation and the Ministry of Public Works and Housing for information, primary data, and connection provided during the course of this study. We also would like to commend enumerators for helping questionnaire survey.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

This research did not receive any specific grants from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. On behalf of all the authors, the corresponding author states that there are no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cecilia, S., Murayama, T., Nishikizawa, S. et al. Stakeholder evaluation of sustainability in a community-led wastewater treatment facility in Jakarta, Indonesia. Environ Dev Sustain 26, 8497–8523 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-023-03056-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-023-03056-9