Abstract

In this paper, we provide an assessment of the challenges of water, waste and climate change in the city of Quito by performing the City Blueprint Approach consisting of three assessment frameworks: (1) the Trends and Pressure Framework (TPF), (2) the City Blueprint Framework (CBF) and (3) the water Governance Capacity Framework (GCF). The TPF summarizes the main social, environmental and financial aspects that may affect urban water management. The CBF provides a clear overview of sustainable urban water management performance and its bottlenecks in municipalities and regions. The GCF comprises nine governance conditions which each consist of three indicators. The GCF provides insight in the most effective improvements to increase the governance capacity to address the identified urban water challenges. Our results show that poor wastewater treatment and long-term drinking water security are Quito’s main water challenges that may be jeopardized given the city’s rapid urbanization and economic pressure. The GCF analysis reveals that cooperation between stakeholders, implementing capacity and citizens’ awareness are the most important conditions for further development to find adequate solutions for Quito’s long-term drinking water security. We also suggest that more attention should be drawn to the transparency, accountability and participation principles. The results of Quito show that the City Blueprint Approach can serve as an affordable quick-scan to facilitate cities in their strategic planning to reach their sustainable development goals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The world is urbanizing rapidly. With a rate of approximately 200,000 people per day worldwide (UN DESA 2014), new inhabitants find their way into the world’s urban agglomerations in search of better opportunities for health, shelter and food. Cities provide opportunities but also pose risks when managed inadequately. Currently, there are more than 400 cities with more than 1 million inhabitants (UN 2012). Besides that, there are 28 megacities (cities with more than 10 million inhabitants), of which Tokyo in Japan is the biggest with 38 million inhabitants, followed by Delhi in India (25 million) and Shanghai in China (23 million). By 2030, the world is already expected to count as much as 41 megacities (UN DESA 2014). This global urbanization challenge is one of the reasons why the United Nations recently organized the Habitat III conference on housing and sustainable urban development in Quito, Ecuador. The conference has had two preceding editions in Vancouver (1976) and Istanbul (1996). Since Habitat I in Canada, the share of the global population that lived in urban areas has risen from 37.9 to 54.5% today (Habitat3.org 2016). Hence, urban challenges are becoming more urgent by the day. Addressing these challenges is important, as high urbanization rates also put more pressure on a city’s management of water, waste and climate change mitigation and adaptation. In order to cope with these challenges, cities need long-term integrated strategies (Koop and Van Leeuwen 2016a).

The Trends and Pressures Framework (TPF) and especially the City Blueprint Framework (CBF) can provide cities with a quick and useful snapshot of their sustainable urban water management and their management of solid waste and climate adaptation (Koop and Van Leeuwen 2015a, b). By involving as many cities as possible into the assessment, a platform is created in which cities can share their best practices and learn from each other (Koop and Van Leeuwen 2016a). At present, 57 municipalities and regions in 30 countries have been assessed (Van Leeuwen and Koop 2017). Recently, we have summarized many best practices of cities in a compendium (Koop et al. 2015).

Urban water issues are often complex and multifaceted and are typified by uncertainty and a general divergence between problem framing and accompanying solutions (Head 2010). As there are many causes that lead to complexity, uncertainty and sometimes disagreement, there is no single best approach to solve these governance challenges. In fact, it is an iterative process that requires governance capacity to find long-term solutions and flexible intermittent targets that can anticipate on emerging barriers and changing situations. Therefore, the water Governance Capacity Framework (GCF) has been developed to reveal the most effective and efficient opportunities to enhance the governance effectiveness to address urban water challenges. Because environmental problemacy may touch the nature of a multitude of different scientific aspects, i.e. hydrological, financial, chemical, social disciplines, it is vital to the success of tackling water governance challenges to create a solid collaboration between different stakeholders on both short term and long term. Moreover, in the search for solutions to water governance challenges, the focus has mainly been on the technological aspects, whereas technological hardware only works within an existing network of institutions and practices (OECD 2015a, b; Bird 2016). Hence, a judicially more enabling and educative environment for stakeholders, aimed at capacity building, may have the potential to make a bigger difference (Bird 2016; Pahl-Wostl 2009).

In the present study, we apply the City Blueprint Approach consisting of the TPF, CBF and GCF on the city of Quito in Ecuador (OECD 2015b; Koop and Van Leeuwen 2016b). We describe (1) the methodological research outline; (2) the results from the three assessment frameworks, (3) the discussion of the results, in which the relevance of our methodology for cities is highlighted. Special attention is drawn to the need for transparency, accountability and participation principles (Water Integrity Network 2016) and their relation to the Blue City Index (Koop and Van Leeuwen 2015a, 2016a).

2 Methodology

2.1 The City Blueprint Approach

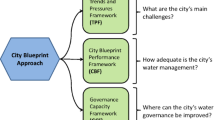

The City Blueprint Approach consists of three complementary methodologies, (1) the Trends and Pressures Framework (TPF), (2) the City Blueprint Framework (CBF) and (3) the water Governance Capacity Framework (GCF) shown in Fig. 1.

Every city has its own social, financial and environmental setting in which water managers have to operate. The application of the City Blueprint Approach followed a learning by doing approach. First, we developed two separate indicator frameworks that embody the distinction between trends and pressures (TPF) and sustainable urban water management performance of a city (CBF).

The TPF comprises twelve social, environmental and financial indicators that may affect water management but can hardly be directly influenced by local authorities (Table 1). Each indicator has been scaled from 0 to 4 points, where a higher score represents a higher urban pressure or concern. The following ordinal classes, expressed as ‘degree of concern’, have been used: 0–0.5 points (no concern), 0.5–1.5 (little concern), 1.5–2.5 (medium concern), 2.5–3.5 (concern) and 3.5–4 (great concern). For seven indicators and sub-indicators we have proposed a scoring method as based on international quantitative standards such as the World Bank, World Health Organization and the Food and Agricultural Organization database Aquastat. The scores are determined using the ranking of the city amongst all available country scores. These scores are not normative and only provide an indication of the urban pressures with respect to global trends. Detailed information on the scoring methods is provided in (EIP Water 2016a). Finally, the Trends and Pressure Index (TPI; the arithmetic mean of all twelve TPF indicators) can be calculated for each city. In the TPF, only indicators that are of concern or great concern (3 or 4 points) are explicitly communicated to the stakeholders (Koop and Van Leeuwen 2015a, 2016a). The TPF includes the following social, environmental and financial indicators: urbanization rate, burden of disease, education rate, political instability, water scarcity, flood risk, water quality, heat risk, economic pressure, unemployment rate, poverty rate and inflation rate. Further details on the data sources, calculation methods and scaling methods and limitations of the TPF are provided by Koop and Van Leeuwen (2015a). This approach has been applied to 45 municipalities and regions (Koop and Van Leeuwen 2015b).

The CBF consists of twenty-five performance indicators that are scored from 0 to 10 and listed in Table 2. The CBF has been critically reviewed, and all indicators of the CBF have been critically assessed on data reliability, scoring method and whether the used data are time-series in order to ensure that the indicators are up-to-date. At the same time, new indicators have been proposed to replace indicators with data problems. Detailed information on the scoring methods of all CBF indicators is provided in EIP Water (2016b). Further details on the data sources, calculation methods and scaling methods and limitations of the CBF are also provided by Koop and Van Leeuwen (2015a). With this approach, 45 municipalities and regions have been assessed (Koop and Van Leeuwen 2015b).

The GCF has been developed as governance appears to be a crucial factor in the sustainability of cities. This conclusion was published both in publications of the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD 2015a, b) and our own work (Koop and Van Leeuwen 2016a). Therefore, we developed a cohesive, comprehensive and applicable Governance Capacity Framework for cities that can (1) cross-compare cities in order to develop a deeper empirical-based understanding of the key enabling governance conditions and identify transferable lessons, and (2) reveal the limiting conditions and thereby formulate pathways for effective and efficient increase in the local governance capacity. The GCF comprises nine overarching governance conditions which each consist of three indicators (Table 3). For each of the twenty-seven indicators, a Likert-type scoring scale has been developed that ranges from very encouraging (++) to very limiting (−−). The GCF has been further operationalized by developing specific questions linked with Likert-type scoring and has recently been applied for the city of Amsterdam (Koop et al. 2017). The methodology is publicly available in order to ensure full transparency (EIP Water 2016c). A detailed description of the methodology and its limitations are provided by Koop et al. (2017).

2.2 Data gathering

The data for the TPF and CBF were gathered in two successive steps. First, an extensive literature study was carried out to determine the preliminary scores for all forty-three TPF and CBF indicators and sub-indicators. These preliminary scores together formed the draft report of the City Blueprint of Quito, which was presented to the authorities in Quito for drinking water (Empresa Pública Metropolitana de Agua Potable y Saneamiento or EPMAPS), solid waste (Empresa pública Metropolitana de Gestión Integral de Residuos Sólidos or EMGIRS) and meteorology/hydrology (Instituto Nacional de Meteorología e Hidrología or INAMHI). Key persons within these organizations were asked to provide their most recent information on all indicators. The data for the GCF were gathered by conducting twenty-six qualitative semi-structured interviews. Fourteen interviews were done with respondents that were experts on (drinking) water in Quito. Twelve interviews were held with citizens, mainly to assess the dimensions of awareness and stakeholder engagement. Of the twenty-six respondents, fourteen were male and twelve were female. These respondents were all accessed first through a cluster sampling strategy, in which ‘experts’ and ‘citizens’ were defined as the two groups in which respondents were to be found (Bryman 2008). In the ‘experts’ category, more subgroups were defined, in the form of which organization these respondents worked for. Examples of these organizations were EPMAPS, FONAG (Fondo para la protección del Agua) or Consorcio Camaren. After these categories were accessed, a snowball sampling strategy was applied in order to reach more respondents. This resulted in a relatively small sample that had a more or less equal division amongst respondents in terms of age and gender, however, less so on the areas of education (all respondents had either a PhD or a university background) and the neighbourhood that respondents lived in (only one out of 26 respondents lived in a neighbourhood in the South of Quito).

2.3 Municipalities and regions

Assessments of the CBF in 45 municipalities and regions in 27 different countries have been reported previously (Koop and Van Leeuwen 2015b, 2016a). In this paper, three more cities have been included, i.e. Bristol and Leicester (both UK), as well as Quito. At this point, there is a strong bias towards cities in Europe. The only cities outside Europe are: Ankara and Istanbul (Turkey), Jerusalem (Israel), Kilamba Kiaxi (Angola), Dar es Salaam (Tanzania), Ho Chi Minh City (Vietnam), Belém (Brazil), Melbourne (Australia), New York City (USA) and Quito (Ecuador). Therefore, we emphasize the strong necessity of extending our work to cities outside Europe.

3 Results

3.1 Analysis of trends and pressures

After the TPF-analysis was carried out for Quito, the scores were classified according to Koop and Van Leeuwen (2015a) into five ordinal classes, varying from no concern to great concern, for each of these 12 TPF indicators as shown in Table 4. The indicators in red are the greatest concerns for the city of Quito.

3.2 Analysis of the City Blueprint

Figure 2 shows the results of the City Blueprint performance analysis. The indicator scores provide a snapshot of sustainable urban water management of Quito. Quito received high scores for access to drinking water and sanitation, as well as drinking water quality, while other areas of sustainable urban water management scored much lower. Quito has a combined sewer system, leading to a score of 0 points for indicator 14 storm water separation. The infrastructure does not collect rainwater separately. This makes Quito vulnerable to flooding and combined sewer overflows during periods of heavy rainfall and, consequently, to serious water pollution affecting both ecosystems and human health. Improvements are needed for wastewater treatment (including energy and nutrient recovery), solid waste recycling, energy recovery and sewage sludge recycling. Asset management is a precarious issue for Quito, not only for its wastewater treatment but also for its drinking water supply as the city has a drinking water leakage rate of 29.3%. The infrastructure investment deficit is a global trend, even in highly developed countries (OECD 2015a): ‘Cities in OECD countries have not solved water management. While they currently enjoy relatively high levels of protection against water risks, they face disquieting challenges, including the proven difficulty of upgrading and renewing existing infrastructures, and heightened uncertainty about future water availability and quality’. The overall score, i.e. the BCI of Quito, is 2.0 points in a range of 0–10.

City Blueprint of Quito based on 25 performance indicators. The range of scores varies from 0 (centre of the circle; low performance) to 10 (periphery of the circle; high performance). Further methodological details are provided elsewhere (Koop and Van Leeuwen 2015a)

3.3 Analysis of the water governance capacity of Quito

Figure 3 shows the results from the GCF analysis based on a limited number of interviews (n = 26). The symbols (−−, −, 0, +, ++) indicate the extent to which an indicator is limiting or encouraging the governance capacity to an address challenges of drinking water scarcity (EIP Water 2016c; Koop et al. 2017). Figure 3 shows that only condition 6 agents of change and 8 financial viability are encouraging. In particular, condition 4 stakeholder engagement process and 9 implementing capacity are found to impede Quito’s overall governance capacity.

A more detailed look at the individual indicators shows that indicator 9.1 Policy instruments appears to be very limiting (−−), and all indicators of condition 4 Stakeholder engagement process are found to be limiting the governance capacity to address water scarcity in Quito.

4 Discussion

4.1 General challenges affecting Quito’s water management

Quito is located in the North of Ecuador and situated in the Andean highlands at an altitude of 2850 m above sea level. Our trends and pressures assessment reveals that the greatest concerns for the city of Quito are urbanization rate, heat risk, economic pressure and inflation (Table 4). Quito has recognized its own climate change vulnerabilities and has already undertaken action to address it. Recently, the city has implemented penalties to stop urban deforestation and to foster ecosystem preservation (Boselli et al. 2010). This is also necessary, as one of the major concerns for Quito is the low share of green and blue area in the urban centre, which leads to vulnerability to urban heat islands and extreme rainfall (Table 4). Indicator 5 water scarcity may be of little concern now, but this may change in the future if inadequate action is taken as a result of the high urbanization rate (Table 4) and because of the relatively high drinking water consumption (Fig. 2). As argued by Buytaert and De Bièvre (2012), this prospect is difficult to ascribe to climate change and population growth is a more determining and more important factor. The global trend of rapid urbanization is also visible in Ecuador. The total share of people living in urban areas in Ecuador is 63.7%, and the annual urbanization rate is 1.9% (CIA 2016). This gives Quito a score of 2.5 on the indicator of urbanization rate (Table 4). The population in the Distrito Metropolitano de Quito (DMQ) was 2.24 million in 2010 (INEC 2010) and is expected to rise with almost 25% to 2.78 million by 2020 (INEC 2013). If this growth rate of 25% per decade continues, the population of the DMQ will double to 5 million by 2050. While this may already be considered a challenge in itself, it may be further reinforced by the fact that the economic situation in Ecuador is rather precarious. The most recent figures indicate that the GDP per capita in Ecuador is $5687.94 per year (IMF 2016). This gives the indicator of economic pressure a score of 3.7, meaning that economic pressure is of great concern to Ecuador (Table 4). Furthermore, the inflation rate in Ecuador was 4% in 2016 (World Bank 2016a). Finally, the latest projection done by the IMF (2016) indicates that in 2017, Ecuador’s economy is predicted to decline by 4.3%. Of all countries in the Latin American and Caribbean region, only Venezuela (4.5%) shows a more rapid decline (IMF 2016).

4.2 The challenges of water resources management in Quito

The analysis of the CBF for Quito (Fig. 3) shows that the city has two major challenges. The lack of wastewater treatment is an immediate major concern. At present, untreated wastewater is discharged into two main rivers around the city: the Machángara and the San Pedro. This results in considerable environmental damage and pollution (Vredeveld 2008; Watkins 2014). However, insufficient financial capacity hampers a direct solution to this issue, as the municipality of Quito has given priority to the construction of a metro network. Consequently, the future construction of a secondary and tertiary wastewater treatment plant to treat almost 100% of Quito’s wastewater has been put on-hold, as the financial means needed to carry out two megaprojects at the same time are lacking. Another major challenge is the city’s drinking water security. Quito is a wasteful city (Koop and Van Leeuwen 2015b), with inadequate solid waste treatment, absence of wastewater treatment and combined sewers leading to combined sewer overflows during the rainy season, in turn resulting in losses of clean fresh water. Besides that, with a water leakage rate of 29.3%, almost a third of all water is lost without being consumed. Finally, with around 200 l per capita per day, the drinking water consumption in Quito is relatively high for a city in the Andean highlands. For instance, Medellín in Colombia has a consumption of only two-thirds of that of Quito. Besides that, there are several other cities in Latin America, Africa and Asia with a lower drinking water consumption. The consumption in Quito is in turn rather low compared to several European and Australian cities. It can therefore be stated that the drinking water consumption in Quito is relatively high, especially compared to other places in the global south (IB-Net 2016). The fact that the indicator of drinking water consumption in the assessment of the CBF actually received a high score (8.7) is the result of the European bias (relatively high water consumption) that is present in the cities that have been assessed with the CBF until now (see Sect. 2.3). This underlines the necessity of further and more detailed research of the CBF and TPF in other municipalities in Latin America, Africa and Asia. A major priority for Latin America is to build the formal institutional capacity to manage water resources and bring sustainable integration of water resources management and use into socio-economic development and poverty reduction. Another priority is to ensure the full realization of the human right to water and sanitation in the context of the post-2015 development agenda (UNESCO 2015).

4.3 Governance challenges of Quito

The governance situation in Quito was analysed with the GCF (EIP Water 2016c; Koop et al. 2017). This framework shows similarities with the principles on water governance, as established by the OECD (2015a, b). However, the OECD principles are of a more general nature and mainly applicable at international, national and regional scales. We argue that cities are a very important scale for addressing the challenges of water, waste and climate change (Koop and Van Leeuwen 2016a). Therefore, we have a local focus and aim to provide an efficient and attainable quick-scan of a city’s governance capacity. Equally so, it enables us to provide recommendations for specific stakeholders, while still maintaining a view on the entire urban water network. The efficiency and workability of the framework makes the GCF a relatively cost-effective approach. It is therefore an attractive way for cities to identify their main governance challenges.

One of the challenges for Quito is to reduce the city’s drinking water consumption. Almost all respondents that were interviewed, experts as well as citizens, indicated that a great deal of the available water is wasted due to inefficient use. A factor that presumably plays a role here is that drinking water is very cheap with estimates of monthly water bills varying from $4 to $7. In part, this is steered by a national Ecuadorian law that obliges municipal governments to keep their drinking water tariff social and affordable for everyone. Therefore, the drinking water price is relatively low which leads to inefficiencies and squandering. We also found that indicator 8.2 consumer willingness to pay was scored as encouraging (+) meaning that consumers are generally willing to pay extra for better services. In order to reduce the water consumption and improve the water services, Quito has to improve its implementing capacity (governance condition 9; Table 3) including indicators 9.1 policy instruments, 9.2 statutory compliance and 9.3 preparedness as shown in Fig. 4. This also holds for the improvement of indicators 1.1 community knowledge as this indicator also scores low.

The low scores for indicators 9.1 policy instruments and indicator 1.1 community knowledge reveal that there is room to improve the drinking water tariff structure. While the national Ecuadorian law prevents municipal authorities from simply increasing tariffs, it is important to consider more differentiation between different classes of consumption. The only differentiation in the tariff structure now is that there are separate tariffs per consumed cubic metre for residential (40 cents), commercial (55 cents) and industrial (62 cents) use. For the residential category, the tariff of 40 cents is only applicable if a household uses less than 10,000 l per month (i.e. 333 l per day). For households that consume between 10,000 and 20,000 l per month and those that consume more than 20,000 l per month higher tariffs are charged. The average daily drinking water consumption is 200 l per capita per day (about 6000 l per person per month) with substantial variations between users. In fact, the differences in consumption between residential, commercial and industrial use are much larger than the differences in the tariffs suggest. Therefore, we recommend that the largest commercial and industrial users should pay a higher price in order to promote a more efficient water use. Before the tariff structure can be revised, however—with or without the suggestions given in this section—further research is necessary to determine the actual differences in consumption. Revising this tariff structure may also increase awareness amongst citizens about the importance of drinking water conservation. Some initiatives have already been introduced in the form of public awareness campaigns (Boselli et al. 2010). However, while experts claimed that the campaigns were relatively widespread, the majority of the citizen respondents indicated that campaigns did not take place on a regular basis and were hardly effective to change people’s behaviour. Some citizen respondents even mentioned that they were not aware of these campaigns at all. This indicates that there is a mismatch between expert opinions and citizen perceptions.

Finally, another major challenge might be to improve the stakeholder engagement process in Quito. A majority of the interviews pointed out that the basis for efficient cross-stakeholder cooperation is limited. The DMQ has two institutions that play an important role in the water network: EPMAPS (the drinking water authority) and FONAG (Fondo para la proteccion del Agua), which restores and protects all the city's water sources. When respondents from EPMAPS were asked whether there were any other stakeholders with whom they regularly exchanged ideas, the most heard answer was either SenAgua (the national water secretariat), the mayor or other departments of the municipality of Quito. However, exchange of knowledge with universities or other institutions was hardly referred to and may be an area for improvement. Besides FONAG, EPMAPS is close to being the only stakeholder with sufficient capacity to operate on such a large scale as they do. Moreover, FONAG is an institution that runs on funding from external donors, primarily from EPMAPS (approximately 90%). This makes FONAG financially rather dependent on EPMAPS. The exchange of knowledge and cooperation across the DMQ between stakeholders, including smaller institutions and the private sector, has resulted in limiting (−) scores for indicators 4.1 stakeholder inclusiveness and 3.3 cross-stakeholder learning. It was striking that indicator 7.1 room to manoeuvre greatly differed between stakeholders. Respondents from FONAG and EPMAPS responded mostly positively when they were asked whether they were given enough time and means to develop new ideas, while the answers of other stakeholders to the same question were less optimistic. Finally, indicator 4.2 protection of core values and indicator 4.3 progress and variety of options are also scored as limiting (−). It is likely that while the core values and variety of options of stakeholders like FONAG or EPMAPS are not harmed, the opposite may be true for (many) others.

4.4 Transparency, accountability and participation principles and their relevance to the BCI

In order to increase support and effectiveness of Quito’s water management, the stakeholder engagement process (condition 4) should be improved. An environment of trust is needed to foster participation of all relevant stakeholders (Huitema et al. 2009; Verhoeven and Tonkens 2011; Horelli et al. 2013). In order to achieve this more emphasizes is needed on principles of transparency, accountability and participation, which can be seen as the building blocks for integrity within the water sector (Water Integrity Network 2016). By sufficient monitoring and evaluation, these principles foster the effectiveness of the decision-making process and may effectively help in combating corruption. First, transparency implies openness and public access to reliable and consistent data and information. According to this principle, citizens should be aware about the decision-making process and know what actions they can take themselves. Secondly, accountability is described as the body of possibilities for actors to hold fellow stakeholders accountable for all things they did and did not do (and to apply appropriate sanctions, if necessary). This process could for example be facilitated by the publication of annual reports and the organization of complaints systems, public meetings and satisfaction surveys. The internet and social media can play an increasingly important role in enhancing accountability. Thirdly, participation implies that ‘all stakeholders, including marginalized and resource-poor groups, are meaningfully involved in deciding how water is used, protected, managed and allocated.’ (Water Integrity Network 2016, p. 58/59). These three principles are included in a number of conditions and indicators of the GCF, such as the condition 4 stakeholder engagement process and in indicator 2.2 information transparency and 9.2 statutory compliance.

Figure 5 shows four diagrams in which the water management performance as summarized in the Blue City Index (BCI) is plotted against four indicators related to these transparency, accountability and participation principles: (1) the Enabling Environment Index (participation; Civicus 2013), (2) Voice and Accountability (accountability and participation; World Bank 2016b), (3) Control of Corruption (anti-corruption initiatives; World Bank 2016b) and (4) Regulatory Quality (accountability and participation; World Bank 2016b). Based on the results of 48 cities, the correlations coefficients are, respectively r = 0.79, r = 0.82, r = 0.83 and r = 0.81. It should be emphasized that correlations are not cause-effect relations. Nevertheless, the independent BCI variable correlates positively and significantly (p < 0.0001) with each of these principles and the World Bank governance indicators. The diagram showing the relationship between BCI and Control of Corruption reveals that all cities with a BCI of 4 or lower, with the exception of Malta and Reykjavik, have a Control of Corruption score lower than 60 out of 100 (World Bank 2016b). Similarly, all cities with a BCI > 4 have a Voice and Accountability score of 60 or higher (World Bank 2016b). These correlations may support our suggestion that the integrity principles are key to improve the stakeholder engagement process and overall governance capacity to address the water challenges in cities and Quito in particular.

5 Conclusion and recommendations

Our study of Quito is an illustration of the global trend of urbanization. With an expected doubling of the population in the next 25–35 years, drinking water security is a major challenge. Our study emphasizes that this is not only a matter of technology. Major improvements can be obtained by increasing the efficiency of cooperation between all stakeholders (including citizens and small firms) and by creating more public awareness and involvement to reduce the high drinking water consumption.

Previous studies showed that there is a need to enhance city-to-city learning. The water-related challenges require a multi-level water governance approach, a long-term strategy, a bottom-up approach and collaboration amongst cities and regions. Therefore, we encourage cities to participate in learning alliances to actively share knowledge and experiences on implementation of state-of-the-art technologies as well as governance experiences. Furthermore, implementation matters. Regular benchmarking, with, e.g. the City Blueprint Approach, based on long-term goals is needed to monitor progress of the transformation process towards adaptive water management and governance in cities. This is the most efficient way to improve sustainable urban water management in light of the urgent challenges we face. This is our main recommendation for UN Habitat. Furthermore, the following conclusions and recommendations are given:

-

1.

The City Blueprint Approach

-

Global agreements on housing and sustainable urban development without monitoring of the transformation towards sustainable cities and networks of collaborating cities will not be effective. Implementation matters and the exchange of knowledge, experience and best practices of cities, i.e. learning alliances of cities can speed up this process.

-

We propose the City Blueprint Approach (Fig. 1) consisting of three complementary approaches that assess cities and may form the starting point for sustainability transformations: the (1) Trends and Pressure Framework, (2) the City Blueprint performance Framework and (3) the water Governance Capacity Framework.

-

-

2.

Results of the City Blueprint Approach for Quito

-

The analysis of the trends and pressures for Quito revealed that the urbanization rate, heat risk, economic pressure and inflation are the main concerns for the city (Table 2).

-

The City Blueprint of Quito (Fig. 2) shows that the main concerns are water system leakages, waste water treatment (including energy and nutrient recovery), solid waste recycling and energy recovery, as well as sewage sludge recycling and energy recovery.

-

The governance capacity analysis (Figs. 3 and 4) shows that two governance conditions in particular can be considered Quito’s main governance challenges, i.e. stakeholder engagement process and implementing capacity.

-

-

3.

Proposed solutions for Quito

-

A revision of the tariff structure, i.e. an increase in the prices of drinking water for commercial and industrial purposes, is proposed to reduce drinking water consumption in Quito. For residential consumption lowering of tariff intervals is proposed as financial incentive for efficient water use.

-

Qualitatively, more public awareness needs to be created to reduce drinking consumption by means of clearer and more frequent campaigns, using internet, social media, rather than just the traditional media and visits to schools. Water rationing can also be considered as an instrument to save water and to create more awareness at the same time.

-

Quito could strive for a more constructive and efficient platform of inter-organizational exchange of knowledge and information. In general, a better participative climate is needed. This also draws attention to the need for more recognition of the integrity principles of transparency, accountability and participation.

-

References

Bird, J. (2016). Why technology alone won’t help smallholder farmers. The source magazine. International Water Association (IWA). PFD Media Group. http://www.thesourcemagazine.org/why-technology-alone-wont-help-smallholder-farmers/. Accessed 24 Aug 2016.

Boselli, B., McGranahan, G., Ortega, M.J.C., Suzuki, H., Vaggione, P., Veit, S., Wilk, D. & You, N. (2010). The Latin American green city index report. Siemens AG Corporate Communications and Government Affairs, Munich, Germany. https://www.siemens.com/entry/cc/features/greencityindex_international/all/en/pdf/report_latam_en.pdf. Accessed 5 July 2016.

Bryman, A. (2008). Social research methods (3rd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Buytaert, W., & De Bièvre, B., (2012). Water for cities: The impact of climate change and demographic growth in the tropical Andes. Water Resources Research, 48 (8). http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1029/2011WR011755/full#wrcr13443-sup-0000. Accessed 20 Aug 2016.

CIA. (2016). Central intelligence agency: The world factbook. Urbanization. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/fields/2212.html. Accessed 19 Aug 2016.

Civicus. (2013). The Civicus 2013 enabling environment index. World alliance for citizen participation. http://civicus.org/eei/downloads/Civicus_EEI%20REPORT%202013_WEB_FINAL.pdf. Accessed 20 Aug 2016.

EIP Water. (2016a). European innovation partnership on water. Indicators of the trends and pressures framework. http://www.eip-water.eu/City_Blueprints. Accessed 21 Nov 2016.

EIP Water. (2016b). European innovation partnership on water. Indicators of the city blueprint framework. http://www.eip-water.eu/City_Blueprints. Accessed 24 Jan 2017.

EIP Water. (2016c). European innovation partnership on water. Indicators of the governance capacity framework. http://www.eip-water.eu/City_Blueprints. Accessed 24 Jan 2017.

Head, B. (2010). Wicked Problems in water governance: Paradigm changes to promote water sustainability and address planning uncertainty. Urban water security research alliance, Technical Report No. 38. http://www.urbanwateralliance.org.au/publications/UWSRA-tr38.pdf. Accessed 20 Aug 2016.

Horelli, L., Saad-Sulonen, J., Wallin, S., & Botero, A. (2013). When self-organization and urban governance intersect: Two cases from Helsinki. Planning theory and practice, 30(3), 286–302.

Huitema, D., Mostert, E., Egas, W., Moellenkamp, S., Pahl-Wostl, C., & Yalcin, R. (2009). Adaptive water governance: Assessing the institutional prescriptions of adaptive (co-) management from a governance perspective and defining a research agenda. Ecology and Society, 14(1), 26.

IB-net. (2016). One click benchmarking (select country—select utility). https://database.ib-net.org/quick?goto=one_click. Accessed 20 Aug 2016.

IMF. (2016). International monetary fund: World economic outlook database, April 2016. https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2016/01/weodata/index.aspx. Accessed 15 July 2016.

INEC. (2010). Resultados del censo 2010 de población y vivienda en el Ecuador—Fascículo provincial Pichincha. http://www.ecuadorencifras.gob.ec/wp-content/descargas/Manu-lateral/Resultados-provinciales/pichincha.pdf. Accessed 20 Aug 2016.

INEC. (2013). INEC presenta sus proyecciones poblacionales cantonales. http://www.ecuadorencifras.gob.ec/inec-presenta-sus-proyecciones-poblacionales-cantonales/. Accessed 15 Aug 2016.

Koop, S. H. A., & Van Leeuwen, C. J. (2015a). Assessment of the sustainability of water resources management: A critical review of the City Blueprint approach. Water Resources Management, 29(15), 5649–5670.

Koop, S. H. A., & Van Leeuwen, C. J. (2015b). Application of the improved City Blueprint framework in 45 municipalities and regions. Water Resources Management, 29(13), 4629–4647.

Koop, S. H. A., & Van Leeuwen, C. J. (2016a). The challenges of water, waste and climate change in cities. Environment, Development and Sustainability. doi:10.1007/s10668-016-9760-4.

Koop, S.H.A., & Van Leeuwen, C.J. (2016b). The challenges of water, waste and climate change in cities. Global Water Forum. Posted on June 13, 2016 in Urban Water. http://www.globalwaterforum.org/2016/06/13/the-challenges-of-water-waste-and-climate-change-in-cities/. Accessed 20 Aug 2016.

Koop, S., Van Leeuwen, K., Bredimas, A., Arnold, M., Makropoulos, C., & Clarens, F. (2015). D2.3. Compendium of best practices for water, waste water, solid waste and climate adaptation. (KWR report 2015.025). http://www.bluescities.eu/project-view/compendium-of-best-practices-for-water-wastewater-solid-waste-and-climate-adaptation/. Accessed 20 July 2016.

Koop, S. H. A., Koetsier, L., Van Doornhof, A., Reinstra, O., Van Leeuwen, C. J., Dieperink, C., et al. (2017). Assessing the governance capacity of cities to address challenges of water, waste and climate change. Report RMG 2017.01. KWR Watercycle Research Institute, Nieuwegein, The Netherlands.

OECD. (2015a). Water and cities: Ensuring sustainable futures. Paris: Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development.

OECD. (2015b). OECD Principles on Water Governance. Paris: Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development.

Pahl-Wostl, C. (2009). A conceptual framework for analysing adaptive capacity and multi-level learning processes in resource governance regimes. Global Environmental Change, 19(3), 354–365.

UN. (2012). World urbanization prospects: The 2011 revision. New York: United Nations.

UN. (2014). World Urbanization Prospects: The 2014 revision. United Nations: Highlights. New York.

UNESCO. (2015). The United Nations world water development report. Water for a sustainable world. Paris: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.

Van Leeuwen, K., & Koop, S. (2017). E-Brochure. http://www.eip-water.eu/City_Blueprints. Accessed 24 Jan 2017.

Verhoeven, I., & Tonkens, E. (2011). Bewonersinitiatieven: Partnerschap tussen burgers en overheid. Beleid en Maatschappij, 38(4), 419–437.

Vredeveld, B. (2008). Striving for Integrated Water Resource Management in Quito, Ecuador: Public Good or Economic and Political Good? Case Study in Water Resources. http://www.fonag.org.ec/upload/aporte_externo/Vredeveld_Case_Studies_Quito_Agua_FINAL.pdf. Accessed 25 Aug 2016.

Water Integrity Network. (2016). Water integrity global outlook. https://www.viawater.nl/files/documents/wigo_book_2016_full.pdf. Accessed 25 Aug 2016.

Watkins. K. (2014). TREND: South America’s wastewater treatment problem. Bnamericas.com. http://www.bnamericas.com/en/features/waterandwaste/trend-south-americas-wastewater-treatment-problem/ Accessed 25 Aug 2016.

World Bank. (2016a). Inflation, costumers price (annual %) http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/FP.CPI.TOTL.ZG. Accessed 21 June 2015.

World Bank. (2016b). Worldwide Governance Indicators http://info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi/index.aspx#faq Accessed 21 June 2015.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all representatives of EPMAPS, INAMHI, EMGIRS, FONAG, CESA, Consorcio Camaren, Acción Ecológica and all citizen respondents who have agreed to participate in our questionnaires and interviews, along with those who facilitated more contacts for new interviews. In particular, for the City Blueprint and Trends and Pressures analyses we owe gratitude to Carlos Espinosa, Diego Paredes and Max Sotomayor for being the first persons within EPMAPS to pick up the concept report of the City Blueprint that was sent around, and for coordinating the rest of the contacts within EPMAPS that were needed to complete this part of the research. Regarding the interviews that were conducted we owe valuable perspectives to Bert de Bièvre and Andrea Vera from FONAG, as a result of very useful in-depth interviews. Carlos Zambrano (Consorcio Camaren) and Ricardo Buítrón (Acción Ecológica) are also thanked for sharing their knowledge and critical comments on a great variety of themes during their interviews. Finally, thanks also goes out to Femke Van Noorloos (Utrecht University) for her critical feedback during the process of writing and on earlier versions of this work. Our work has been financed by KWR Watercycle Research Institute in the context of Watershare®: sharing knowledge in the water sector (http://www.watershare.eu/). It is a contribution to the European Innovation Partnership on Water of the European Commission and more specifically to the City Blueprint Action Group (http://www.eip-water.eu/City_Blueprints), coordinated by both Dr. Richard Elelman of Fundacio´ CTM Centre Tecnològic and NETWERC H2O and Prof. Dr. C.J. van Leeuwen (KWR Watercycle Research Institute). The European Commission is acknowledged for funding BlueSCities in H2020-Water under Grant Agreement No. 642354.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Schreurs, E., Koop, S. & van Leeuwen, K. Application of the City Blueprint Approach to assess the challenges of water management and governance in Quito (Ecuador). Environ Dev Sustain 20, 509–525 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-017-9916-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-017-9916-x