Abstract

Self-assignment, a self-directed method of task allocation in which teams and individuals assign and choose work for themselves, is considered one of the hallmark practices of empowered, self-organizing agile teams. Despite all the benefits it promises, agile software teams do not practice it as regularly as other agile practices such as iteration planning and daily stand-ups, indicating that it is likely not an easy and straighforward practice. There has been very little empirical research on self-assignment. This Grounded Theory study explores how self-assignment works in agile projects. We collected data through interviews with 42 participants representing 28 agile teams from 23 software companies and supplemented these interviews with observations. Based on rigorous application of Grounded Theory analysis procedures such as open, axial, and selective coding, we present a comprehensive grounded theory of making self-assignment work that explains the (a) context and (b) causal conditions that give rise to the need for self-assignment, (c) a set of facilitating conditions that mediate how self-assignment may be enabled, (d) a set of constraining conditions that mediate how self-assignment may be constrained and which are overcome by a set of (e) strategies applied by agile teams, which in turn result in (f) a set of consequences, all in an attempt to make the central phenomenon, self-assignment, work. The findings of this study will help agile practitioners and companies understand different aspects of self-assignment and practice it with confidence regularly as a valuable practice. Additionally, it will help teams already practicing self-assignment to apply strategies to overcome the challenges they face on an everyday basis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The success of any software project depends heavily on the execution of the related management activities (Pinto and Slevin 1988). These activities primarily include organizing the software teams, allocating tasks, and monitoring time, budget, and managing resources (Boehm 1991; Jurison 1999) and carried out differently depending on the project management approach followed. In traditional software development, a project manager plays a key role in task allocation (Guide 2001; Nerur et al. 2005; Stylianou and Andreou 2014). The duties of a project manager include planning, assigning, and tracking the work assigned to the project teams. Work is typically allocated keeping in mind the knowledge, skills, expertise, experience, proficiency and technical competence of the team members (Acuna et al. 2006).

In contrast to the traditional development processes, agile software development offers a different approach towards managing the software development cycle particularly task allocation. Instead of the manger assigning the tasks, the team members pick tasks for themselves through self-assignment. This concept of self-assignment is unique to agile software development and emerges from the two principles in the agile manifesto i.e. ‘The best architectures, requirements, and designs emerge from self-organizing teams’, ‘Build projects around motivated individuals. Give them the environment and support they need and trust them to get the job done’ (Beck et al. 2001). Even though self-assignment is not directly specified by these principles, but they build the motivation and highlight the significance to study self-assignment.

In theory, agile methods, particularly the Scrum methodology, encourage self-assignment for the allocation of tasks among team members (Hoda et al. 2012; Hoda and Murugesan 2016). Self-directed task allocation or self-assignment is also considered a fundamental characteristic of self-organized teams (Vidgen and Wang 2009; Deemer et al. 2012; Hoda and Murugesan 2016; Strode 2016; Hoda and Noble 2017). Typically, agile methods like XP, Scrum, and Kanban encourage team members to assign tasks or user stories to themselves (Schwaber and Sutherland 2011; Deemer et al. 2012; Hoda and Murugesan 2016). The different agile methods refer to this notion through different terminologies such as self-assigning, signing up and pulling (Beck 2005; Lee 2010; Deemer et al. 2012). We refer to it as self-assignment in this study. Unlike agile practices that have been well-studied such as pair programming (Williams et al. 2000), daily stand-ups (Stray et al. 2016), and retrospectives (Andriyani et al. 2017), it is unclear how self-assignment works in agile projects making it a promising area to study.

In practice, the transition from the manager-led allocation to self-assignment is easier said than done. This transition may not happen in one day due to multiple reasons. The manager may not trust teams and individuals (Hoda and Murugesan 2016; Stray et al. 2018) and resist adopting new ways of working and delegates tasks. The team members may not be comfortable to self-assign tasks themselves due to lack of confidence. Some members may always pick familiar tasks, and others may prefer self-assigning exciting tasks (Vidgen and Wang 2009; Hoda and Murugesan 2016; Strode 2016; Masood et al. 2017b). The team members may self-assign low priority desirable tasks ignoring the high priority ones (Masood et al. 2017b). This indicates that self-assignment can be challenging to practice. The related research does not cover the various aspects of self-assignment in-depth such as comparing the benefits of practicing self-assignment to manager-led allocation, challenges of practicing self-assignment. Additionally, limited information on the strategies agile practitioners follow to overcome the challenges of self-assignment increases the gap in the current research. Therefore, there is a need to investigate how self-assignment works in agile teams to answer several open questions such as: What leads to practicing self-assignment? What facilitates self-assignment in agile teams? What constrains self-assignment in agile teams? How do agile practitioners overcome the constraining conditions?

This research is part of a broader study which aims to cover various aspects of self-assignment in multiple phases. As part of our future work, we plan to study various aspects of self-assignment in multiple phases. Some of these aspects are understanding the self-assignment process, motivational factors to self-assigning tasks, role of manager in self-assignment. The focus of this paper is to investigate what leads to practicing self-assignment, conditions influencing the self-assignment process, strategies to overcome the constraining conditions, and any consequences of adopted strategies. It is to be noted that other aspects such as the self-assignment process which includes how and when self-assignment is practiced in agile teams, in what form teams and individual self-assign tasks, and factors individuals keep into account while self-assigning work items are part of the complete doctoral study on self-assignment. Some of the data from phase1 of this study has been published (Masood et al. 2017a; Masood et al. 2017b) and reported as preliminary research on self-assignment in related works in this paper (in Section 2 and 5.1).

This study involved 42 participants representing 28 agile teams from 23 software companies based in New Zealand, India, and Pakistan. We collected data in two phases through pre-interview questionnaires, semi-structured interviews, and observations of agile practices such as daily stand-ups, iteration planning meetings, and self-assignment during task breakdown sessions. As a result of applying data analysis procedures, we present our grounded theory of making self-assignment work that describes what leads to and facilitates self-assignment, strategies used by the agile teams to make self-assignment work despite constraining conditions, details of the phenomenon of making self-assignment work, along with causal conditions, context, intervening conditions, strategies, and consequences. Additionally, we provided a list of practical implications and recommendations for agile teams, scrum masters and managers practicing self-assignment or teams that are transitioning into self-assignment.

The main contributions of this study are that it illustrates in-depth theoretical knowledge of self-assignment as a task allocation practice in agile teams. Future researchers can refer to this study for understanding the different aspects of self-assignment. Secondly, the practical strategies and recommendations presented in this study will contribute to the software industry by helping managers and agile teams overcome the hurdles and challenges faced in practicing self-assignment.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 describes related works, section 3 summarizes the research method, sections 4 presents the findings of this research and Section 5 discusses the findings and compares with related work with recommendations for agile community and future researchers. Section 6 concludes the paper.

2 Related Works

Software project management comprises of a set of activities which include but are not limited to project planning, scope definition, cost estimation and risk management (Boehm 1991; Jurison 1999). In the conventional process of software development, the activities for project planning such as project schedule, resource and task allocation are taken care of by the project manager (Nerur et al. 2005; Stylianou and Andreou 2014). Resource and task allocation are considered important activities in the project planning phase irrespective of what methodology is used in software development. The project manager is considered to be a single point of contact with the sole responsibility of taking the task allocation decisions and managing the project scope and team (Stylianou and Andreou 2014). The project manager role is both critical and challenging as the competence of the project manager and how well they plan and execute these activities significantly contributes to the success of the project. In fact, the managers’ decisions on allocating developers and teams to project tasks and scheduling developers and teams are considered one of the key indicators of success of a software project (Stylianou and Andreou 2014).

With the advent of agile software development more than two decades ago, task allocation is no longer the lone responsibility of a manager (Nerur et al. 2005); rather, it is meant to be shared within an empowered development team. Agile introduced light-touch management (Augustine et al. 2005) giving autonomy, empowerment and flexibility to development teams and valuing customers through engagements without forfeiting governance (Beck et al. 2001; Augustine 2005; Carroll and Morris 2015). One of the fundamental characteristics of agile methods is that they support task assignment as a team- and individual-level activity and disregard the traditional role of the project manager w.r.t. tasks delegation (Nerur et al. 2005). Typically, teams practicing agile methods self-assign technical tasks or user stories during the development cycle (Hayata and Han 2011; Hoda and Murugesan 2016). Agile methods are seen to term this self-assignment differently such as “volunteering”, “signing up”, “committing”, and “pulling” (Beck 2005; Lee 2010; Deemer et al. 2012). Empirical studies have been conducted on novice (Almeida et al. 2011; Lin 2013) and experienced agile teams (Masood et al. 2017a; Masood et al. 2017b) to study task allocation decisions, strategies and workflow mechanisms. These studies inform us that tasks assignment in Agile teams is not the sole responsibility of the manager or other team members.

Self-directed task allocation or self-assignment is acknowledged as a fundamental characteristic of self-organized teams (Vidgen and Wang 2009; Deemer et al. 2012; Hoda and Murugesan 2016; Strode 2016; Hoda and Noble 2017). Yet, research on self-assignment in agile software teams has been limited in scale and depth. The focus of such studies has mostly been around task allocation in global software development (Simão Filho et al. 2015). Mak and Kruchten (2006) proposed an approach to address issues that managers face for task-coordination and allocation in global software development environments using agile methods. The proposed solution and Java/Eclipse-based distributed tool ‘NextMove’ was meant to facilitate project managers in the prioritization of current tasks and generation of suitability ranking of team members against each available task helping project managers in making day-to-day task allocation decisions. Other researchers have proposed approaches (Mak and Kruchten 2006), models (Almeida et al. 2011) and frameworks (Lin 2013) to address task allocations problems in global software development contexts where agile was being used. The unique context of global software development implies the challenges of task allocation were more to do with the teams being distributed rather than them practicing agile methods.

Self-assignment of tasks has also been observed in open source software (OSS) development in both commercial and non-commercial projects (Crowston et al. 2007; Kalliamvakou et al. 2015). In an empirical study (Crowston et al. 2007), developers’ interaction data from three free/libre open source software (FLOSS) projects was examined to understand the process by which developers from self-organized distributed teams contribute to project development. Self-assignment was reported as the most common mechanism among five task assignment mechanisms, the remaining being, (a) assign to a specified person, (b) assign to an un-specified person, (c) ask a person outside project development team, and (d) suggest consulting with others. Task allocation in FLOSS development was seen to not involve any micro-management or task delegation through a project manager or an employer. Since these teams are composed of volunteers, the task assignment was mostly based on the personal interests of the contributor. The study identified several drawbacks such as people picking work, they are not good at or lacking prior experience which could impact the quality of the contribution and may require review by others. Similarly, developing code management practices and designing and using such tools is challenging when multiple developers contribute to the same parts of the project.

Existing research on self-assignment in co-located, e.g. non-distributed and non-open source, agile teams is very limited. Self-assignment in new agile teams is seen to happen as a gradual process, retaining a manager’s role at the beginning for tasks delegation (Hoda and Noble 2017). Our preliminary work conducted on a dataset of 12 agile practitioners from four teams of a single company based in India confirmed five main types of task allocation approaches in agile teams: manager-driven, manager-assisted, team-driven, team-assisted, and or self-directed (Masood et al. 2017a). With time and experience, agile teams seem to dispose of the command and control attitude and are instead seen to move towards manager-assisted or team-assisted assignment and, in some cases, towards practicing self-assignment over time (Hoda and Noble 2017; Masood et al. 2017a). As a part of that preliminary work, we also identified some motivational factors that agile developers take into account while self-assigning tasks such as technical complexity, business priority, previous experience with similar tasks, and others (Masood et al. 2017b). However, we do not know in-depth what strategies the teams use to make self-assignment work despite certain intervening conditions. In this study, we investigated how self-assignment works in agile teams in a way that it’s not only beneficial to individuals, teams, and projects but also to the organizations.

Here we presented an overview of the related works of task allocation in agile software development. We will revisit them in light of our findings in Section 5, comparison to related work.

3 Research Method

After considering a number of potentially suitable methodologies such as Case study (Yin 2002), Ethnography (Fetterman 2019), and Grounded Theory (Glaser 1978; Strauss and Corbin 1990), we adopted Grounded Theory (GT). The interest of researchers towards generating a theory to explain how agile teams make self-assignment work using a cross-sectional dataset not limited to few cases or organizations led the researchers to use GT. The intention is to uncover self-assignment from empirical data rather than validating any existing theories or hypotheses. Also, the focus of this study is around understanding the process, investigating strategies, and exploring underlying behaviours, and influencing factors, and so GT was particularly well-suited.

GT comes in various versions, Classical/Glaserian, Strauss and Corbin, and Charmaz Constructivist, we employed the Strauss and Corbin version due to several reasons:

-

a.

It follows a more prescriptive approach than classical GT (Coleman and O’Connor 2007; Kelle 2007) leading the researcher through clear guidelines, and, as a novice GT researcher, the first author found this useful.

-

b.

It builds on research question which is open ended and drives the direction of research (Strauss and Corbin 1998).

-

c.

It provides an additional analytic tool for axial coding in the form of a coding paradigm, which can help GT researchers identify the categories, sub-categories, and their relationships much earlier in contrast to classical GT theory where this emerges after multiple rounds of analysis (Seidel and Urquhart 2016).

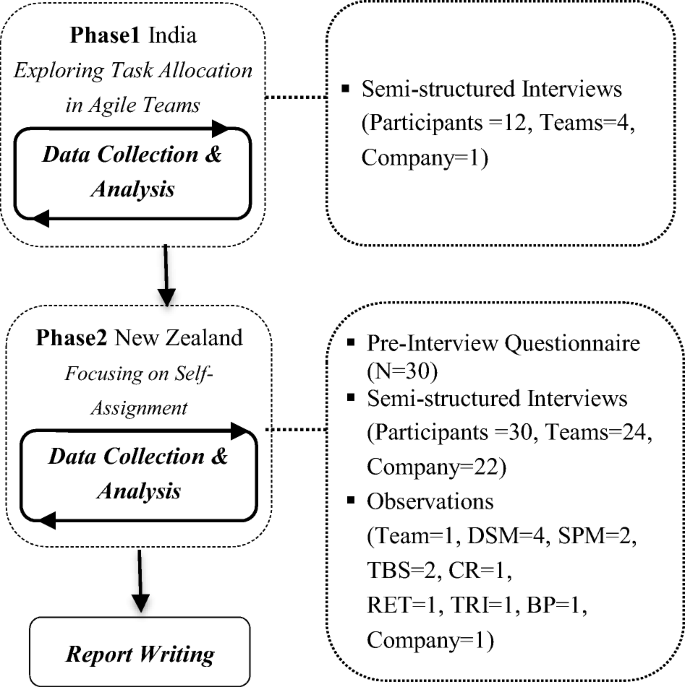

The study comprises of two phases, each including multiple iterations of data collection and analysis as shown in Fig. 1. In the first phase, we explored the task allocation process in Agile teams. In the second phase, we narrowed down our focus to self-assignment as a specific task allocation process. We collected the data in multiple rounds, data of each round was analysed before collecting more data to ensure theoretical sampling. This was done until we reached theoretical saturation. This is evident from our interview questions which were revisited and revised to meet the narrowing focus of the GT study. The primary data sources for phase1 were face-to-face interviews and for phase2 were pre-interview questionnaires, face-to-face semi-structured interviews, and team observations of agile practices. We describe these in the following sections. The additional documents, such as interview guides, pre-interview questionnaire etc. can be found as supplementary material (Masood et al. 2020).

3.1 Data Collection & Analysis (Phase1)

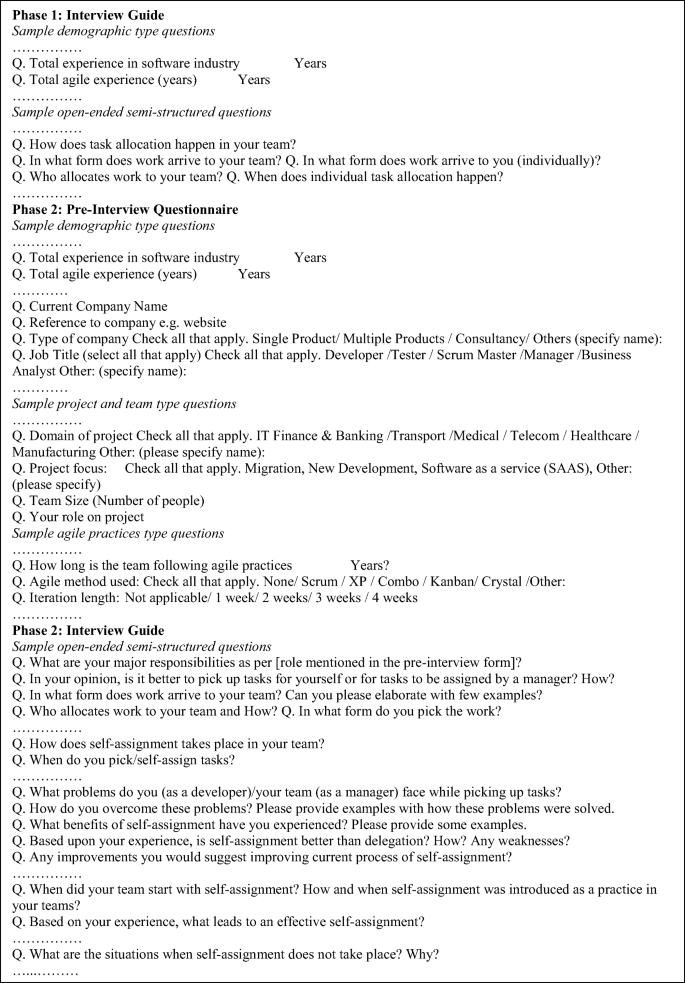

Phase1 aimed to investigate the task allocation process in agile teams. The focus was to study the task allocation strategies in agile teams. The authors collectively prepared the interview guide (all authors), conducted semi-structured interviews (second author), transcribed the interview recordings (first author) and analysed (all authors) to reduce any bias and improve internal validity through researcher triangulation. The interview guide designed to collect data for this phase focused on four main areas (Fig. 2):

-

a.

professional background: e.g. please tell me about your professional background

-

b.

agile experience e.g. how long have you been using agile practices?

-

c.

current team and project, e.g. which practices have been used regularly on this project?

-

d.

task allocation practices e.g. how does task allocation happen in your team?

We sent invitation to the “Agile India” group to recruit participants for phase1. An Indian software company responded with a willingness to participate in the study. We interviewed 12 participants in-person from that company. Table 1 summarizes the demographics of the participants (P1-P12), highlighted in lighter shade of grey. Each interview took approximately 30–60 min. These face-to-face interviews helped to record the verbal information and capture the interviewee’s expressions and tone (Hoda et al. 2012). All these interviews were recorded and transcribed for analysis. The data collected from phase1 was manually added in NVivo data analysis software. The data collected helped in developing an initial understanding of task allocation in agile teams. We applied open coding, the Strauss and Corbin GT’s procedure of data analysis (Strauss and Corbin 1990) on participants’ transcribed interview responses. During open coding, we labelled the data with short phrases that summarize the main key points. These were further condensed into two to three words, captured as codes in the NVivo. As a result of data analysis, different concepts from similar codes emerged, one the most prominent of which was task allocation through self-assignment. Others included manager-driven, manager-assisted, team-driven, and team-assisted task allocation (Masood et al. 2017a). The results of phase1 directed us to focus on self-assignment as the substantive area of the study in the next phase.

3.2 Data Collection (phase 2)

Phase2 aimed to investigate self-assignment as a task allocation practice and explore how agile teams make self-assignment work. The goal of the study was to build a theory to identify what leads to and facilitates self-assignment process, what strategies are used by the agile teams to make self-assignment work, and the consequences of these strategies. As with phase1, the authors collectively prepared the instruments i.e. pre-interview questionnaire and interview guide (all authors), conducted interviews (first author), and analysed them (all authors) to mitigate potential bias. The pre-interview questionnaire gathered basic and professional details of the participants and the interview guide was primarily used to facilitate the interviewer and the interview process to collect details around various aspects of self-assignment. The interview guide was refined throughout to accommodate the exploratory nature of the study. All the interviews conducted during phase2 were transcribed for analysis either by the first author or the third-party transcribers. The pre-interview questionnaire and the interview guide used to collect data during the phase2 focused on the following main areas (Fig. 2):

-

a.

professional background: e.g. please tell me about your professional background

-

b.

agile experience e.g. how long have you been using agile practices?

-

c.

current team and project, e.g. which agile practices have been used regularly on this project?

-

d.

Various aspects of self-assignment, e.g. How does self-assignment take place in your team? What problems do you (as a developer)/your team (as a manager) face while picking up tasks? Please provide an example with how these problems were solved.

Following Grounded Theory’s guidelines of refinement and constant narrowing-down, the interview focused on self-assignment and its various aspects. From phase1, we noticed that capturing participants’ demographics data was taking a significant amount of time during the interview, sometimes leaving interesting aspects unexplored. So, for phase2, demographics and supporting details such as professional background, agile experience, current team and project related details were gathered using a pre-interview questionnaire filled by each participant before their interview.

To recruit participants for phase2, we sent invitations to multiple online groups, and those who showed willingness to participate verbally or through emails were contacted. Social networking sites such as LinkedIn, Meetups groups such as “Agile Auckland”, “Auckland Software Craftsmanship” served as useful platforms to recruit participants in New Zealand. Once a participant contacted us showing their willingness, we requested them to share basic and professional details through the pre-interview questionnaire. The details gathered from the pre-interview questionnaire also helped us limit our context to individuals and teams who practice self-assignment at some level and with varied frequency (always, frequently, rarely, and occasionally). Agile teams not practicing self-assignment were out of scope. We conducted 30 more interviews (28 in-person and 2 via Skype). These semi-structured interviews were conducted for 30–60 min per participant. Table 1 summarizes the demographics of the participants involved in the phase2 of study in darker shade of grey.

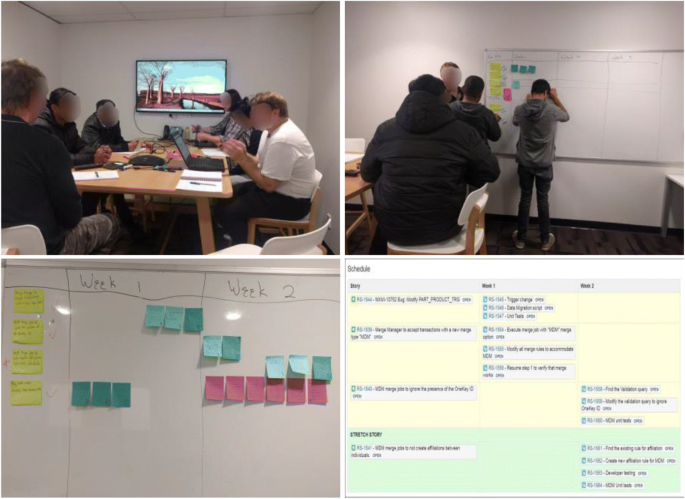

The first author attended multiple sessions of agile practices while observing agile team ‘T11’ comprised of 7 members. This included attending four daily stand-ups of duration 10–15 min each, two one-hour sprint planning meetings for two sprints, two-hours task-breakdown sessions for two sprints, one 30-mins code-review session, four squad triage sessions of 10–15 min each which focused on the outstanding issues requiring clarifications, discussions or any decisions, one backlog prioritization 30 mins, and an hour long retrospective meeting. Figure 3. captures some glimpses of the sessions attended during these observations. Observations of practices supplemented our understanding of the self-assignment process, practices, and strategies followed by the teams.

The entire study involved 42 participants represented through numbers P1 to P42 for confidentiality reasons. Table 1 summarizes the demographics of all the participants. Participants were working for software companies developing software solutions for healthcare, accounting, finance, transport, business analytics, and cloud services. Participants were working in New Zealand (71.5%) and India (28.5%) and varied in gender with 86% male and 14% female. Age and professional experience varied from 2 to 25 years of experience. They were directly involved in the software development with job titles as developer, consultant, product owner, architect, lead developer, and scrum master. Most of the participants were practicing Scrum, whereas some used a combination of Scrum and Kanban. They used agile practices such as daily meetings, customer demos, pair programming, iteration planning, release planning, reviews and retrospectives.

3.3 Data Analysis (phase 2)

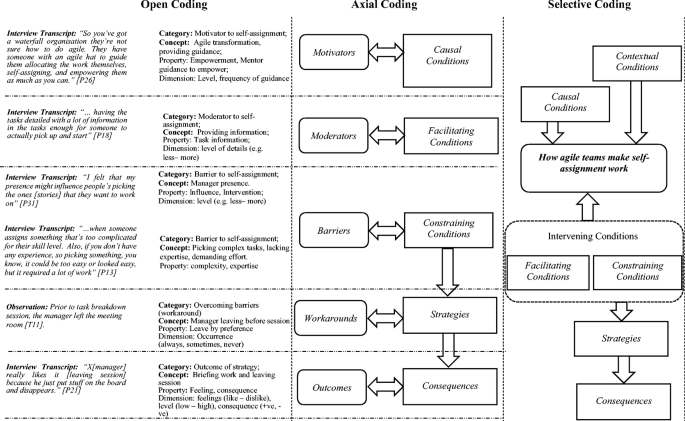

The Strauss and Corbin’s version of GT comprises of three data analysis procedures: open, axial, and selective coding (Strauss and Corbin 1990). All these procedures were interwoven and were conducted mainly by the first author with the underlying steps such as defining emerging codes, concepts, sub-categories, and categories being thoroughly discussed on an on-going basis, and finalized with the co-authors, including a GT expert. The use of analytical tools such as diagramming, whiteboarding, and memo writing facilitated the analysis process. The quantitative data was collected using a pre-interview questionnaire and the qualitative data in the form of transcripts, observation notes, and images were uploaded in NVivo. Figure 4 provides a step-by-step example of applying all these procedures.

Open coding

We started the data analysis with open coding, in which all the interview transcripts were analysed either line by line or paragraph by paragraph as appropriate and represented with short phrases as codes in the NVivo software. With constant comparison within same and across different transcripts, we grouped similar codes to define a concept, a higher level of abstraction. Sometimes, multiple concepts were generated from single quotes as shown in a few examples in Fig. 4. These concepts were identified in the data and sometimes defined in terms of their properties and dimensions to contextualize and refine the concepts. The extent to which this could be done relied on the level of details were shared by the participants. Then, we integrated concepts into the next level of data abstraction, categories. The outcome of open coding was a set of concepts and categories.

Figure 4 illustrates the open coding and constant comparison procedures using multiple examples, starting from the raw interview transcripts of the participants [P13, P18, P21, P26, P31], and observation notes [T11] listing the category, concept, property and dimensions for each transcript excerpt as examples. For example, excerpt from P13 resulted in multiple concepts ‘picking complex tasks’, ‘lacking expertise’, ‘demanding effort’. All these were grouped under the category ‘barriers to self-assignment’. These came from the answers to questions like ‘What problems and challenges do you (as a developer)/your team (as a manager) face while picking up tasks?’. In addition to concepts and categories, we also identified properties and dimensions. Properties are ‘characteristics that define and explain a concept’ and dimensions are ‘variations within properties’. For example, one of the participants P31 shared that their presence influenced people’s self- assignment choices and decisions. This led us to classify ‘intervention’ as a property, and ‘intervention level’ as a dimension (see Fig. 4). The open coding process was applied on the entire data set (interviews and observations) of the study. This way all the conditions, strategies and consequences were identified, categorized, and reported. The categorisation was discussed during regular team meetings and refined with constant feedback from the co-authors.

Axial coding

Next, we applied axial coding, a ‘process of systematically relating categories and sub-categories’. Sub-categories are also concepts that refer to a category providing further clarifications/details. Strauss recommends using ‘analytical tools’ to define relationships between categories and sub-categories (Strauss and Corbin 1990). One such tool is Coding Paradigm which guides the researcher to illuminate the conceptual relationships between concepts/categories by identifying the conditions, actions/interactions, and consequences associated with a phenomenon. Strauss proposed variants of the coding paradigm to facilitate axial coding (Urquhart 2012). All of these are used as analytical tools and organization schemes (Corbin and Strauss 2008) which help to arrange the emerging connections and identify the relationships. To the best of our knowledge, this is one of the very few software engineering research studies (Giardino et al. 2015; Lee and Kang 2016) that apply and illustrate an in-depth application of Strauss and Corbin’s Grounded Theory, including the use of their “coding paradigm” (in Fig. 5, presenting the Phenomenon, Context, Causal Condition, Intervening Conditions, Strategies, and Consequences).

We applied the coding paradigm as it assembled our data well, the structure of the coding paradigm mapped well to our emerging categories (Strauss and Corbin 1990; Corbin and Strauss 2008). The coding paradigm contains different terminologies such as context, causal conditions, intervening conditions, action/interactional strategies, and consequences. Table 2. states the Strauss and Corbin definitions of the coding paradigm terminologies (2nd column) with how we applied them to our study on self-assignment (3rd column). Our categories from open coding such as motivators, barriers, moderators, outcomes are mapped to the coding paradigm terminologies such as causal conditions, intervening conditions, consequences (represented by the symbol  in Fig. 4). The relationships between the sub-categories (other categories) were represented as per the terminologies of the coding paradigm (defined in Table 2, represented by ⇨ in Fig. 4). For instance, we know from the definition that causal conditions are the reasons why teams adopt self-assignment and leads to the phenomenon under study. Similarly, we know that the strategies to work around challenges of self-assignment result in different consequences. All the relationships between categories and sub-categories were iteratively and constantly validated with the data (within each participant’s data and across other participants’ data) throughout the analysis process. This was done in multiple analytical iterations and the relational statements evolved with continuous reflections over time.

in Fig. 4). The relationships between the sub-categories (other categories) were represented as per the terminologies of the coding paradigm (defined in Table 2, represented by ⇨ in Fig. 4). For instance, we know from the definition that causal conditions are the reasons why teams adopt self-assignment and leads to the phenomenon under study. Similarly, we know that the strategies to work around challenges of self-assignment result in different consequences. All the relationships between categories and sub-categories were iteratively and constantly validated with the data (within each participant’s data and across other participants’ data) throughout the analysis process. This was done in multiple analytical iterations and the relational statements evolved with continuous reflections over time.

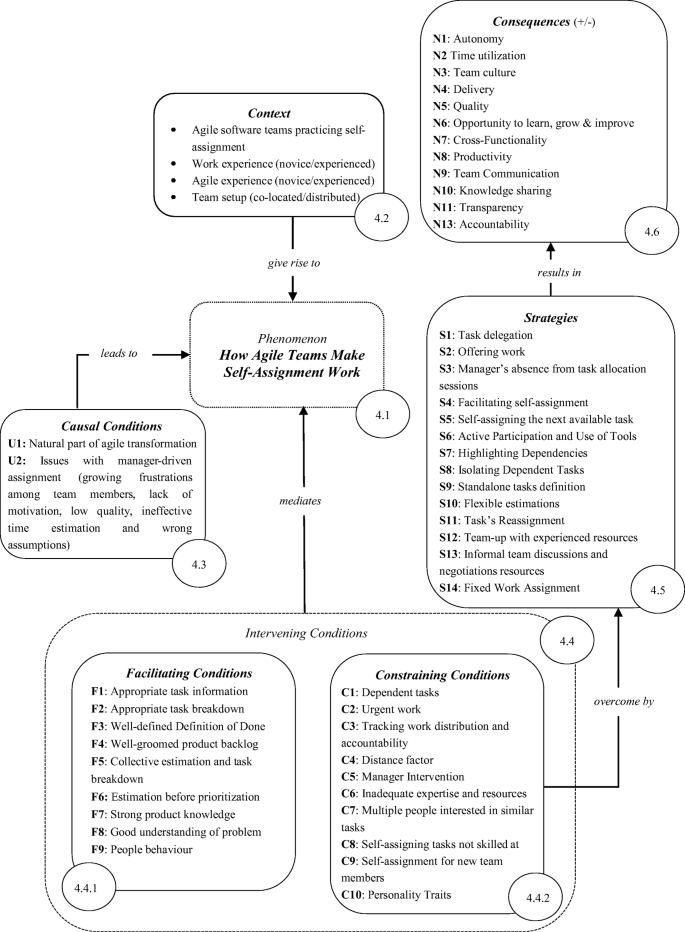

In Selective Coding, we started building a storyline presenting the essence of our study where each sub-category and category captured a part of the whole story of making self-assignment work (presented in Fig. 4). How agile teams make self-assignment work emerged as the most prominent and central phenomenon from our data analysis process (described in section 4) that was binding all the sub-categories together, strengthening the relationships identified during the axial coding. It was during the selective coding, we confirmed which relational phrases such as ‘mediates’, ‘overcome by’, ‘give rise to’ were fitting well to our entire theory model in Fig. 5. It was also during the selective coding, when theoretical saturation was reached and no new concepts, categories or insights were identified. Then, finally we revisited and refined the categories to make sense of the entire theory explaining the phenomenon.

4 Results

We present our grounded theory of making self-assignment work in agile teams. The section is structured to follow Fig. 5. which visually represents our theory and illustrates its categories in the following sub-sections in detail. In the following sections, we present all our findings that comprise the overall theory (Fig. 5), including plenty of quotations from the raw data and sample observation notes/memos.

The grounded theory of making self-assignment work in agile teams explains the (a) context (described in section 4.2) and (b) causal conditions that give rise to the need for self-assignment (described in section 4.3), (c) a set of facilitating conditions that mediate how self-assignment may be enabled (described in section 4.4.1), (d) a set of constraining conditions that mediate how self-assignment may be constrained (described in section 4.4.2) and which are overcome by a set of (e) strategies applied by agile teams (described in section 4.5), which in turn result in (f) a set of consequences (described in section 4.6), all in an attempt to make the central phenomenon, self-assignment, work.

4.1 The Phenomenon – How Agile Teams Make Self-assignment Work

One of the key findings of our study is that self-assignment is not as easy and straightforward as might be expected. It comes with challenges and requires a set of strategies to make it work in practice. Our findings indicate clearly that self-assignment does not simply imply picking whatever tasks team members want. Development team members are bound to choose tasks based on their business needs and priorities as stated by P30.

‘It’s not just like, go out there and choose whatever you want to work on…it’s like team commits, and whatever they’ve committed, they’ve selected tasks from a triaged [prioritized] list and they’re committing to that work.’ – P30, Lead Developer

We identified that transitions to self-assignment does not happen automatically but teams with a positive mindset, an encouraging Scrum Master who values teams and empowers autonomy, and the use of effective strategies lead to effective self-assignment smoothly. As such, the key phenomenon identified in our analysis was “how agile teams make self-assignment work”.

4.2 The Context– Contextual Details and Conditions

Beyond the demographics captured in the pre-interview questionnaires (participant age, gender, experience, etc.), other contextual details emerged during our in-person interviews and while observing team practices to understand how self-assignment works. The variation in the team setup (co-located, distributed), work experience (novice, experienced) and team’s agile experience (novice, transitional, mature) can have influence on the facilitating/constraining conditions and corresponding strategies. We will see that the contextual conditions vary in their application. For example, strategies identified to facilitate self-assignment in distributed team contexts were different to those for co-located team context. Similarly, strategies for new team members were different from those for mature, experienced teams. While manager intervention may not be a constraining condition for teams with flat structure without managers and so the strategies cannot be applied in such settings. Teams self-selecting their tasks at the beginning of the sprint may have different constraining conditions when compared to teams which self-assign the tasks during the sprint. The contextual details are best understood in relation to the related conditions and strategies, and so these contextual details are weaved into our descriptions in the following sub-sections.

4.3 The Causal Conditions – Leading to Adopting Self-assignment

In this study, the participants were questioned about why they chose to self-assign. In result, we identified many different reasons for adopting self-assignment. The most common cause was it being a natural part of the agile transformation represented as U1. Other causes reported by the participants are related to issues with manager-driven assignment referred by U2. We used the term ‘manager’ to refer to all management roles (i.e. project managers, scrum masters, and team leads).

4.3.1 U1: Natural Part of Agile Transformation

The most common rationale [N = 10] behind opting to practice self-assignment evolved naturally with an understanding of the scrum methodology (Deemer et al. 2012) and agile manifesto (Beck et al. 2001). As teams adopted agile methods, they also became more self-organized.

‘...It [self-assignment] naturally started off that individuals in a team are responsible to go and select ... So, I think it was just our understanding of the Scrum methodology and agile Manifesto’ –P42, Technical Lead

4.3.2 U2: Issues with Manager-driven Assignment

Issues with the manager-driven assignment approach caused some participants to drift towards self-assignment. These issues include growing frustrations among team members, lack of motivation, low quality of work and inaccurate estimates.

Growing frustrations among team members

A quality assurance analyst P36 identified frustrations as a cause that led to the team adopting self-assignment. The Scrum Master may not always be aware of frustrations of the team, as explained by the participant, recalling a particularly challenging experience:

‘It was one Quality Assurance Analyst, she broke down, saying that I can’t do it anymore. She was required [assigned] to test something in the cloud, introducing her in just the last minute… When I saw her collapsing down, I had lots of empathy with her. And then in our retrospective, I also started exploding and I’m not taking any allocation. This is all going wrong. The scrum master went back, she came again, and she said, I will not allocate anything, you, as a team, sort out the distribution.’ –P36, Quality Assurance Analyst

Lack of motivation

Some participants described that team members are more motivated and happier when they have some level of ownership and when they see value in what they’re doing. For example, participant P41 highlighted lack of motivation as a reason to replace the manager-driven task allocation with self-assignment and participant P40 revealed happiness among team members with self-assignment.

‘Prior to this [self-assignment] they [team members] were less motivated’ –P41, Senior Architect

‘With self-assignment people are happier. They feel more in charge of what they’re doing, they have that sense of ownership.’-P40, Consultant

Low quality

It was also indicated that when it was someone else in the team assigning the tasks, the quality of the work was not that good. This could be because the person assigning the task may not always be well-aware of an individual’s technical skills and interests.

‘[Earlier] most of the time it was Scrum Master or the PM’s say who’s going to do what….and the quality of the output wasn’t that great’ – P37, Head of Product Delivery

This in a way is correlated with lack of motivation as work quality is good when the team members are motivated and more committed.

‘When they [team members] are motivated, I see them delivering exceptional results’ –P41, Senior Architect

Inaccurate estimates

It was also reported that the shortcomings of manager-driven task allocation helped participants take up self-assignment. One of these shortcomings was the possibility of making wrong assumptions because the manager was not always fully aware of the actual implementation details, underlying technical risks, and the expected time to perform a task, potentially leading to inaccurate estimates.

‘When a manager hands it [user stories/tasks] down, often they’ll either make estimates, and then they’ll hold you to their estimates and then there are all sorts of problems. – P15, Technical Lead & Scrum Master

The developer P16, agreed with the Scrum Master’s point of view.

‘Team deciding on their own capacity is better than being handed down [estimates] because if a manager puts their finger in the air and makes a wrong assumption, that sends unrealistic message to the business’ – P16, Developer

4.4 The Intervening Conditions – Conditions Influencing Self-assignment

These causal conditions led agile teams to adopt and practice self-assignment. Next, we will see what and how the intervening conditions influence the self-assignment process. We have elaborated these conditions as factors that facilitate or constrain our phenomenon. The conditions that facilitated the self-assignment process are described as facilitating conditions in sub-section 4.4.1 and the conditions that hindered the process are mentioned as constraining conditions in sub-section 4.4.2. These are listed in Table 3.

4.4.1 Conditions Facilitating Self-assignment

There are certain facilitating conditions, which are broad, general conditions that influence the phenomenon. The phenomenon can be facilitated provided these conditions are met. In this study, we identified nine facilitating conditions classified into three categories. Some of these are specified as attributes of the artefacts and agile practices, others as attributes of people.

Artefacts-related facilitating conditions

Agile teams create artefacts in the course of product development. These artefacts are useful in tracking product progress, providing transparency and prospects for inspection and adaptation to the stakeholders (Schwaber and Sutherland 2011). Some of the common Scrum artefacts are Product backlog, Sprint backlog, Definition of Done (DoD), etc. (Deemer et al. 2012). Attributes of agile artefacts were reported to facilitate self-assignment, such as F1 (appropriate task information), F2 (appropriate task breakdown), F3 (well-defined Definition of Done), and F4 (well-groomed product backlog). These are detailed through examples below.

F1: Appropriate task information. Requirements-related work items in agile are generally defined as epics or features (for high-level requirements) and user stories or tasks (for lower level requirements) (Bick et al. 2018). High-level work items are generally allocated to the development teams who break them down into user stories and technical tasks either individually or collectively. Providing enough information on the work items was seen to be of vital importance to effective self-assignment and is identified as the most important facilitating condition as stated by a majority of the participants [P14, P18, P19, P20, P22, P26, P28 - P31, P37, P40-P42]. The team members understand the problem and feel confident to self-assign if sufficient details are provided against the work items. Having comprehensive information not only helps the development team understand the problem and propose solutions but also identifies the task dependencies involved and the impact it makes on other modules. Particularly, this supports the junior team members who are initially hesitant to ask for help. Additionally, with enough details on the tasks, it is quite unlikely that team members will have to go to other team members for getting clarifications and instead rely on themselves. This is accepted by both the managers and the developers as indicated in quotes below.

‘It [task] should have enough details, that’s the most important thing.’ –P22, Developer

‘You’ve got to make sure that you have enough information either in the card or in the explanation so that they (team members) do feel confident with taking on that task.’ – P14, Technical lead & Developer

F2: Appropriate task breakdown. Appropriate level of granularity while breaking down tasks is seen to drive the work allocation in the right way. This indicates that it’s not just the task’s comprehensiveness that makes it understandable to team members, but the way the breakdown is done also adds clarity on it. For example, while defining a form if developers start writing about every field name as a task, most of the time will be taken defining it which is not useful in any way. If the tasks are not broken down appropriately it could lead to ambiguity resulting in assignee’s lack of confidence to complete the task on time. A more decent breakdown of tasks facilitates the individuals in making reasonable choices as it makes the tasks clearer, more understandable, and easier to do.

‘The key is not to split tasks to such a smaller level so that it becomes very difficult to allocate. You want granularity but you want a certain level of granularity’ – P18, Software Architect

F3: Well-defined Definition of Done. DoD provides clarity to work item’s (feature, story, or task) definition and is considered met when it fulfils the customer’s acceptance criteria. If the acceptance criteria or DoD is vague and lacks clarity, then there is a potential risk of wrong interpretations of the work items. The team members may not pick them to avoid discussions required to gain clarity or assume the task could be harder to complete. They may not pick them considering that fleshing out the right acceptance criteria would be an additional task. Well-defined done criteria help in making effective choices while self-assignment tasks, as stated by P27.

‘It is important that done criteria is properly defined at the beginning of the sprint or whenever the task is available, with insufficient DoD they [team members] are unlike to choose the work’ – P27, Developer

F4: Well-groomed product backlog. Agile teams perform product backlog grooming and refinement sessions mainly to refine and improve user stories, and to estimate and prioritize the backlog items (Deemer et al. 2012). A well-refined structure in the product backlog seems to contribute as a facilitating factor towards effective self-assignment. The backlog should not be only well-groomed but also consistent so that it’s not undergoing extraneous changes in priorities. With too many changing priorities, the backlog can be unwieldy and challenging to manage as indicated by P29.

‘If you have an environment where the backlog of stories coming up, or switching the priorities, or changing every day, then it’s hard’ – P29, Developer & Scrum Master

Well-defined and detailed artefacts and concepts such as the technical tasks or user stories, product backlog and definition of done facilitated self-assignment.

Practices-related facilitating conditions

Facilitating conditions consisted of practices such as F5 (collective estimation and task breakdown) and F6 (estimation before prioritization).

F5: Collective estimation and task breakdown entails a combined effort involving everyone in the team (Deemer et al. 2012; Hoda and Murugesan 2016). This helps in getting input from all the team members, sometimes defending their individual estimates, sharing assumptions and knowledge, keeping all on the same page, therefore providing all team members the opportunity to choose any task. This collective estimation and effort support collective awareness of the task. No one can disregard a task as the team members collectively perform the breakdown and estimation of tasks, share the information, help and indicate the right direction so the chances of mistakes and inaccurate estimates can be less.

‘During the planning we do everything together, sharing, creating the tasks, it means that everyone knows and owns those tasks. So, no one could say I didn’t grab a task, it’s not my estimate’ – P15, Technical Lead & Scrum Master

F6: Estimation before prioritization. In a few cases, it is seen as important to estimate tasks well in advance of the sprint. Having estimations a few iterations ahead of the sprint was seen to help the teams practice self-assignment since it ensures a long list of tasks is available to choose from providing more options for the team to select and exercise autonomy. This provides an opportunity to get prepared for the work in advance allowing the team to move tasks as per their and business needs. As a result, team members can commit to tasks of their choice.

‘We made sure that we were about 4 to 5, maybe more, Sprints ahead in estimation at any point in time. So the problem with prioritising before estimation is that when the team commits, the set of options is very small so they don't actually feel like they’re exercising autonomy. So by giving us the flexibility to be 5-6 Sprints ahead, allowed the team to go, ‘you know, if we do this thing that’s in Sprint number 4 now, you know, we’re preparing the groundwork for something that’s coming later, let’s move that up’. And now the team starts self-organising or practicing autonomy’ – P30, Lead Developer

As reported, this worked well in an experienced autonomous team of developers who were free to bring items into the backlog, based on their requirements. The team was doing estimations within a two-week Sprint, product grooming three times, every two weeks. It should be noted that estimating 4–5 sprints in advance may not be practical in all settings due to time constraints. However, estimating 2–3 sprints ahead may not be that unrealistic as a trade-off for the team to self-organize and practice autonomy.

People-related facilitating conditions

Some attributes of the people involved in the self-assignment, such as F7 (In-depth product knowledge), F8 (Good understanding of problem), F9 (People behaviour including technical self-awareness, sense of ownership, understanding of importance) are also reported to mediate the self-assignment process.

F7: Strong product knowledge. Strong in-depth product knowledge makes developers and testers familiar with different areas of the application. That makes them more competent, and they are more comfortable to make the right choices when self-assigning tasks. It is likely to build their confidence, increase productivity, and improve their work quality.

‘Well naturally whoever knows the area of work, the piece of software or the problem that needs to be addressed that’s most productive’ – P20, Lead Developer

F8: Good understanding of problem. Also, understanding the work items and associated problems plays an important role as acknowledged by both developers and Scrum Masters. With an incorrect understanding of a problem, it is possible that the attempts to resolve the problem will also be flawed. Therefore, having a mutual and accurate understanding of the problem is important for self-assignment. Developers are typically seen reluctant to choose the tasks that they do not understand well as indicated by P29.

‘Having a good understanding of the stories that need to be done, I think that is important. If I have many questions about a story, I can’t self-assign, because I don’t know what needs to be done.’ – P29, Developer & Scrum Master

F9: People Behaviour. Additionally, other behaviours and attitudes that were reported as facilitating conditions by multiple experienced managers and team members were: self-awareness of technical abilities as a team or as individuals and having sense of ownership and commitment. If the individuals and teams are well-aware of their technical abilities, they would make reasonable choices individually or collectively.

It has been acknowledged both by the managers and agile team members that when people select a task, they have the freedom to choose their own direction which boosts their motivation to perform better.

‘The most important thing in my view is people have buy-in, they commit and agree on the tasks that they want to go and do. And I think that gives them a sense of ownership, it gives them a sense of choice and commitment.’ –P42, Technical Lead

With this autonomy and opportunity to choose, one can naturally grow responsibility and commitment towards that work enabling a sense of ownership. On the other hand, if the team members are being forced to work on something, they are less likely to own it. This indicates if these attitudes are manifested in individuals, they can help to facilitate the self-assignment process.

4.4.2 Conditions Constraining Self-assignment

We identified ten conditions that were seen to constrain self-assignment through posing some challenges. Similar to the facilitating conditions, these fall under Practices, Artefacts and People-related conditions.

Artefacts-related constraining conditions

The only constraining condition reported in this study under artefacts is C1 (Self-assignment for Dependent tasks) which is listed below.

C1: Self-assignment for Dependent tasks. Some tasks rely on other tasks to be completed before they can be started. This can sometimes be challenging as some developers may pick work which may have a dependency on other tasks in the sprint. If the team members are unaware of these dependencies, they will likely self-assign such tasks, which can lead to slow or minimal progress.

‘Certain stories are dependent, but we avoid that as much as possible’ – P32, Developer

‘We try to avoid having dependant tasks, but it happen’ – P16, Developer

Practices-related constraining conditions

C2 (Urgent Work), C3 (Tracking work distribution and accountability), and C4 (Distance Factor) are identified as constraining conditions influencing the self-assignment process.

C2: Urgent Work. Many participants indicated that urgent work coming during the running sprint is one of the most influential factors that constrains practicing self-assignment [P13, P14, P16, P18, P19, P21, P23, P25, P28, P30, P33-P36, P40, P41]. When there is some high priority urgent task, e.g. a high impact bug in some part of the application or a show-stopper support reported by the customer, then self-assignment is constrained. An example of such work is shared below.

‘When product owner is getting feedback from the app stores about…..being annoying for customers…., Well guys, it’s really important that we squeeze this in as customers are really complaining about it’ – P23, Test Analyst

This is sometimes disturbing for the team members as it supersedes their ability to choose and takes away time and resources from the ongoing sprint. One of the participants disclosed this as follows:

‘Obviously, there are urgent stuff that just gets put onto my desk’ –P19, Developer

Another participant indicated that they could refuse to take up such urgent things but find it culturally incorrect. This could be because knowing the urgent nature of the work, and still not showing a willingness to work on such task may not please the manager or contradicts the team or business interest.

‘Although we can say no, we’re not gonna do it, but it wouldn’t be culturally nice to say that’ – P23, Test Analyst

C3: Tracking work distribution and accountability. Multiple team members choosing the tasks on the go during the running sprint gets challenging as no single individual is directly accountable for any specific issue which is reported later on. This is because multiple people contribute to one story by committing to different tasks. For instance, a story X may consist of 10 tasks, and if these tasks are done by five different developers, it could be hard to backtrack an issue as so many developers have been involved in the development of the story as stated by one participant. However, this is not reported to happen frequently.

‘You may get [into situations], like if there’s a problem found [later], there may be less ownership on, maybe five people worked on a story, well, whose bug is that, yeah (laughter).’ – P15, Technical Lead & Scrum Master

As the team members are given freedom to choose tasks they may not choose wisely and make wrong estimations. The reasons could be that they try to impress a manager by taking more, long or complicated tasks or want to show their efficiency by working harder. This can sometimes lead to situations where the product is delayed due to the fact the person is not able to finish the tasks they committed. They are given a choice, but their wrong choice led to significant delays. However, managers sometime feel that people are not choosing enough tasks for a sprint.

‘The only bit of it[self-assignment] that I don’t like is it can get a little bit unambitious in terms of what can I get done. Like it’s easy to have an expectation set of 20 points per person, per Sprint for example. And mentally that’s what I tend to think …But sometimes I wonder if there would be more that could be done if people worked harder...And I felt like either somebody wasn’t working on their tasks or it wasn’t getting done’ – P31, Development Manager

One the other hand, one of the participants P20 shared the experience of penalizing by over-committing more tasks in a particular sprint and acknowledged picking amount of work that they are sure to accomplish.

I [team member] remember my took on a lot of work through, and hadn't finished things at the end of the sprint and so things were uncompleted and he [Manager] doesn't like that. So, I felt like trying to work hard is penalized. So, what happens now is I’ll do all the work in the sprint, won’t take on anything else’ – P20, Lead Developer

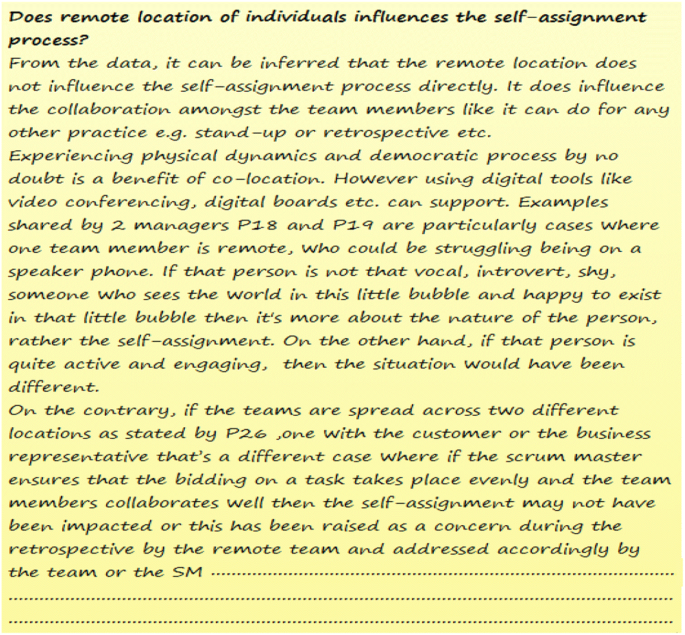

C4: Distance Factor. The distance factor, or remote location of teams and working across different time zones, seems to influence the application of self-assignment in some way as brought up by a couple of participants. This especially happens when half of the team is sitting close to the Product Owner or the client while the other half don’t have Product Owner or the client representative. They don’t get as much connectivity as the collocated ones and particularly disadvantaged when people don’t speak very clearly during discussions, missing some important piece of information. Similarly, the collocated members get an edge of expressing their interest for any task grabbing it earlier, enjoy the opportunity to show their enthusiasm and collaborate with the client in person. When the development team is collocated, it enhances communication and coordination of activities while picking tasks, e.g. sharing prior knowledge on a task, less or no pair programming with a remote team member. Working with teams in different time zones is more challenging. There is a good chance to struggle to get a task of interest if teams are operating in different time zones.

One of the team members who worked remotely revealed that being away from team physically sometimes jeopardized practicing self-assignment in its true essence.

‘Sometimes we are on remote call, client and US team are together in same room, when they start picking the tickets, having discussions, everyone is interested doing that work they have advantage of raising their hands they will quickly say ‘Hey, I'm interested ...they have advantage.... auction never starts here’ –P1, Tech Lead

‘If some person is on a different time zone, he’s still sleeping, and the job comes in today, how can he know, how can he assign himself on that? I’m going to do it.’ – P33, Tester

One manager shared how working dynamics such as real physical presence, missing facial expressions and gestures, sharing thoughts and skipping offline talks and different insights can undermine the self-assignment for people working remotely.

‘If you’re not in the room with seven other people, you’re on a speaker phone, you can’t see what’s going on, don’t experience the dynamic. And then people vote because you’re not seeing the hands go up, you’re not influenced by the democratic process. So, you have a different thought or insight because everybody else has been talking about it offline or whatever the case may be so, there’s a gap.’ – P30, Lead Developer

While observing one of the stand-up meetings [T11], one developer who used to work remotely for a couple of days every week due to some personal situation seemed disadvantaged. The daily stand-up was a lot harder, he had to dial in for it, and the team had to relocate to the recreation area for making the call. While observing the stand-up, we also noticed that the people weren’t speaking very clearly, so he probably did not hear half of it and even his voice broke up once during the call. Above we have included a memo (Fig. 6.) saved in NVivo on to exemplify the influence of distance factor on making self-assignment work.

Some intervening conditions apply to a specific context as identified by memo (See Fig. 5.), e.g. distance factor is specified as one of the constraining factors, but this only applies when one or more team members are working remotely. These constraining conditions lead to certain action/interaction strategies which are adopted by agile individuals and teams as presented in Fig. 7.

People-related constraining conditions

Some of these constraining conditions are associated to people’s behaviours. These are C5 (Manager Intervention), C6 (Inadequate expertise & resources), C7 (Multiple people interested in similar tasks), C8 (Self-assigning tasks not skilled at), C9 (Self-assignment for new team members), and C10 (Personality Traits).

C5: Manager Intervention. Some technical managers or leads were often found proposing or suggesting their way of doing things. This emerged as another intervening condition in letting team members practice self-assignment. The managers may not necessarily push their decisions, but team members may not like this interference while performing the task. They rather prefer doing it on their own without any directions as shared by P19.

‘But there definitely been times when he [manager] looked over and given suggestions. So, I don't really mind but I prefer him to not be there just so I can do it [task] on my own.’ – P19, Developer

On the other side, manager intervention can also be inadvertent. One manager talked about instances when it’s not their intention to assign tasks but the gestures like looking at someone during the daily stand-up, asking a question about a task or discussing an issue gives them an indication that the manager wants them to pick it. Another manager accepted that there are still times when they could not resist assigning a task, limiting the team members to make their own choices.

‘I guess there are still times where I might go up to someone and effectively assign them the task, because I’ve asked them a question and then I’ve said can you look into this... So that still does happen.’ – P31, Development Manager

Similarly, while observing team’s sprint planning meeting, this was also noticed that the manager having an eye contact with one of the developers while elaborating a story might have influenced the developer choosing the story as that team member was seen to self-assign that story.

C6: Inadequate Expertise & Resources. As another constraining factor, sometimes inadequate or limited resources are seen to influence the smooth execution of self-assignment. As an example, in a team with one tester, there is no option of choosing tasks. As an exceptional case, when most of the members in the team happened to be away, then also self-assignment is kept back.

‘There’s no self-assignment, because the Quality Assurance Analyst is a single person, he cannot, it’s only the Quality Assurance Analyst who can take up the thing –P29, Developer & Scrum Master

Also, sometimes managers and scrum masters have to assign tasks to keep a balance for equal distribution of work among the resources. For instance, if there is a high priority task that must be assigned, it goes to the person who is free but if it was not high priority, it could just go in the queue. Participant P21 shared an example of this as:

‘I [Scrum Master] tend to have something in my mind about who might be assigned partly because I want to make the logistics work, this person becomes free, this person has some other work therefore it probably goes to the person who is free.’ – P21, Scrum Master

From these examples, it is evident that sometimes when the resources are not fully available the manager has to purposely suspend self-assignment. Also, to keep a check and balance. This indicates that the availability of expertise and resources also impacts the self-assignment process.

C7: Multiple people interested in similar tasks. There are times when many developers/testers are interested in picking same tasks. This could be due to the level of ease or interest, potential for outside endorsement, opportunity to learn new technology etc. However, it could sometimes get challenging to not let the same people pick the fascinating ones, keeping an equal balance among all the team members and getting the full benefits of self-assignment.

‘As you’re [team] working down the board, getting stories done, you know, maybe the one [task] everyone wants to do is story number 4…’ –P3, Technical Lead & Scrum Master

C8: Self-assignment tasks not skilled at. Different instances were revealed around people’s reactions as constraining factors towards self-assignment. Developers and testers are seen to choose tasks that they might be interested in doing to explore and learn new things, and this sometimes ends up into low productivity, needing more help or making wrong estimations. This is because they may perceive the level of difficulty and effort required to complete the task incorrectly. The task could be more challenging and time-consuming than initially anticipated. But an encouraging manager has to outweigh these, firstly for the promising benefits of employee satisfaction through some control over what they pick for themselves and secondly allowing them to try, learn and improve their skills. However, this can be challenging as the task may need to be estimated accordingly or given more time for completion. It is also reported that sometime someone picks a task they are not skilled at and struggle later on which is indirectly encountered as another challenge with self-assignment.

‘A person might go and take a task that they’re not the right person for. So e.g. there might be a very specialist task in a security piece of work, and a person who might not have self-awareness might go and pick it up. And rather than them doing it in an hour, it might take about three days’ –P42, Technical Lead

C9: Self-assignment for new team members. Newcomers are neither well-acquainted with their fellow members nor with the team’s development processes in the beginning. They require some time to settle in, understand development practices, build trust and co-ordination with other team members. Similarly, introducing new members to self-assignment seems challenging, irrespective of being a novice or experienced professional they need some assistance to understand the team’s task assignment process in addition to getting an understanding of the technical domain and code base.

‘They’re [new member] just starting to know everything [process & project] and in a complex project as this, if you ask me, I would like them [Manager] to assign as I don’t know a thing about it’ – P33, Tester

C10: Personality Traits. Some people struggle in having confidence in their own choices, it might be part of their personality, or the culture they come from or due to lack of self-confidence. For instance, the shy or introvert members may find it intimidating to self-assign a task. They sit back while others self-assign tasks leaving behind the ones not picked up by others. Then, there are also less-confident members who may have the right skillset and knowledge to perform the task but are scared to raise their voice or are under the impression that other team members may be more capable of performing that task quickly and more efficiently. They have a natural tendency to believe in other opinions more and seen more comfortable with working on tasks assigned by others.

‘There are members who don’t want to pick something, it’s hard for them to step in front of the team and take something, rather than getting something. And that is a personal attitude, and that’s hard and if you have a team where more than one is like that, it’s hard to counter…’ – P32, Developer

4.5 Actions/interactions Strategies– To Workaround Challenges of Self-assignment

The constraining conditions described in sub-section 4.4.2 steer the individuals and teams to adopt strategies for overcoming the undesirable effects of the phenomena. We identified 14 strategies, which we describe in this sub-section and are illustrated in Fig. 7.

S1: Task delegation

Task delegation is the most common strategy [N = 16] used for an urgent piece of work (C2) and when the team is short of resources (C6). Our analysis suggests that very high priority tasks are assigned directly to the person considered best suited, the specialists as indicated by a lead below.

‘So typically, I’d pick one of the more specialist people who know what’s going on and say ‘hey, can you please jump in and grab this task?’ – P14, Technical lead & Developer

Sometimes the task is allocated to the most suitable person with the desired technical skillset, at other times it may be directed to a person who has done similar work in the past as expressed by Participant P21 through an example:

‘We made a change in partition manager [module] three months ago, and this is related to that change. ‘You did that change, so you understand it. Can you go and do it?’ – P21, Scrum Master

This can result in a quick solution to the problem but was perceived as a threat to autonomy as the team members are no longer allowed to choose their own tasks, rather the assignment is being enforced on them through their manager.

S2: Offering work

An uncommon strategy [N = 6] practiced to address urgent work (C2) is that the manager will post a message through online channels, like slack or email, or during the stand-up indicating the high priority of the task and let the team members choose. Listed is an example where true autonomy can be easy to practice by providing the opportunity of choice as a variant of self-assignment in the form of volunteering.

‘X [Manager] posts a message that this ticket is priority, can someone have a look and then everyone will volunteer’ – P33, Tester

S3: Manager’s absence from task allocation sessions

To minimize the influence of the manager (C5), teams are seen to conduct the task allocation sessions without them. It helps them choose their tasks without the manager’s persuasion.

‘Had to persuade dev manager that [stepping out] would work and worked in other places till he reckoned and agreed the team was a bit more mature and he would step back letting them assign the tasks themselves and do their own breakdown.’ –P21, Scrum Master

Managers seem to have this self-realization too as expressed by P31.

‘I felt that I could be a little bit coercive too by saying yeah, X would be best to work on that one, and then suddenly he’s assigned to it by default only because I said that. And so that’s why I don’t participate in those meetings.’ – P31, Development Manager

We observed during a sprint planning meeting [T11], the manager briefed all the user stories to the team, and they collectively estimated them. Then the manager left the meeting room, and the team conducted the task breakdown session without him.

S4: Facilitating self-assignment

The scrum master is seen to play an influential role for ensuring an even distribution of work within the team (C3). When managers believe people are not choosing enough tasks for a sprint, it is the scrum master who is seen investigating the underlying cause. People may not be picking more tasks due to low confidence, no experience, lack of interest, other commitments such as working on other business as usual tasks, or to help others. In exceptional cases, when multiple team members show interest in similar tasks (C7), sometimes it’s the scrum master who intervenes to keep a balance ensuring everyone gets equal opportunities to learn and grow by experimenting new things.

Similarly, individuals and teams new to agile practices (C9) sometimes are seen struggling to adopt to that level of self-organization due to multiple reasons such as team member’s background, experience and attitude. It was shared by the scrum master [P21] that they started practicing self-assignment only to be part of the project initially i.e. practicing it for new development work. This was done to persuade their technical manager who had concerns around meeting a deadline when client demanded quick completion of work. SMs’ shared their experiences, when they had issues trying to get some members to take ownership and operate autonomously. There are diligent members who have no trouble picking tasks voluntarily, while it is also not unusual that there are members who barely self-assign unless everyone else in the team has self-assigned tasks. They rely on the SM to suggest them what tasks to self-assign. In such cases, scrum masters and managers are seen to play a primary role to encourage team members to volunteer and steer the team in the direction of self-organization as indicated below.

‘I am trying to get people in the way of thinking more with agile mindset. But also try not to push them too hard or too fast, cos then they kind of resist it’ –P29, Developer & Scrum Master

‘We’re trying to build a culture where people volunteer for stuff when Sprint planning happens. But we don’t have a team that is currently groomed with that attitude and mindset. So, we’re coaching them to be at that stage, so we ask them to call themselves out on what they want to work on, because they’re unsure of what to pick up first’– P26, Product Owner

Similarly, a good coaching conversation or one-on-one mentoring by the scrum master is reported as a strategy to help people who are not comfortable in raising their voices and choosing work for themselves (C10). However, as indicated by the participant this does not happen straightaway and demands a supportive scrum master and consistent team support to help shy, introverted people make choices and feel confident in their decisions.

I had one colleague, he was very silently, he was not really talking, he was a wonderful developer, he was really, really good, but he was not able to step in front of the team and take something. And I worked very long with him together, and we ‘taught’ him, and mentored him on a friendly way. It took a while, a long while ……… Because I taught him, I was kind of his mentor … and he learned it. – P32, Developer

This also goes back to the type of culture the team possesses. In an environment where people can have open discussions and address such problems either on individual or team level, this is easy to address. On an individual level, it is mostly the scrum master, mentor or coach who is responsible to facilitate the self-assignment process providing the guidance and helping them to overcome individual problems towards self-assignment. On the team level, the development team members work together to facilitate self-assignment, e.g. senior peers are also seen to play a significant role to support the junior team members.

S5: Self-assigning the next available task

When many people show interest in the same tasks (C7), for most of the teams the sprint rule of self-assigning the next available task automatically handles such situations. The first person who runs out of work can take the next available task on the storyboard. A senior participant shared that even being a senior developer, if he likes to do a task, at times he misses out because of this rule. This naturally addresses the issues of short of work, unequal distribution, under-committing, and over-committing of tasks (C3). In this scenario, it is to be ensured that there are enough tasks on the board so that no one gets short of work. It was observed during the sprint planning meeting [T11] that the scrum master included few stories as ‘could have’ to ensure everyone has work. These were treated as stretch tasks for the sprint.

‘As you’re[team] working down the board, getting stories done, you know, maybe the one[task] everyone wants to do is story number four, but no one can go to it until story number three has no more tasks they can work on. So, but the first person who runs out of tasks above that story will grab the task.’ – P15, Developer & Scrum Master

S6: Active participation and use of tools