Abstract

We assess public spending efficiency of 20 Latin American countries over the period of 2000–2019, computing data envelopment analysis efficiency scores. For the Public Sector Performance composite indicator, we use the annual data of socio-economic indicators, and for the input measure we consider Total Public Spending as a percentage of GDP, by spending category. The results show that public spending during the period under study increased, but that overall governments were not efficient, as on average they could have used 27% less spending to achieve the same levels of performance. On the other hand, governments could have increased their performance by 18% whilst maintaining the same level of spending. The most-efficient countries were Chile, Guatemala, Panama, and Paraguay, with the least efficient being Bolivia, Venezuela, Nicaragua, Suriname, and Brazil.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The role of fiscal policy broadly covers the accomplishment of the three Musgravian functions: allocation of resources, distribution of income, and the stabilisation of the economy. As governments endeavour to accomplish these roles, it is important to analyse the quality of government spending and how effective the use of public resources has been, especially in a region which mostly depends on revenues from commodities, which is non-permanent income. Accordingly, this paper analyses government expenditure and its efficiency for 20 Latin American countries between 2000 and 2019. This cross-country analysis enables drawing relative comparisons for the region as a whole and highlights which countries used their economic resources better and performed well within the same region.

The reality in Latin America is that government spending increased over the last two decades, and at a relatively greater speed since 2010. With the onset of the global financial and economic crisis, most of the region's countries implemented expansionary fiscal policies that were intended to increase aggregate demand. Spending on subsidies, transfers, and certain social programmes was accordingly increased, which, although it helped mitigate the impact of the crisis on the most vulnerable sectors, in some cases it led to a permanent rise in government spending. Consequently, public spending as percentage of GDP in the 20 countries comprising our analysis increased by 7 p.p. of GDP from 2000 (19.3%) to 2020 (26.3%). In addition, the average spending in the Latin American countries under study in the areas of health, education, and social protection increased from representing 1.5%, 3.2%, and 3.4% of GDP in 2000, to representing 2.8%, 4.3%, and 5.6% of GDP in 2020, respectively.

Our contribution to the literature lies in the study’s focus on the analysis of public sector efficiency in Latin American countries, especially with regards the provision of both public sector performance indicators and (output and input) efficiency scores ensuing from the implementation of the data envelopment analysis. As mentioned in Afonso et al. (2020), less evidence is available for Asia, Africa, or Latin America regarding public sector efficiency. Hence, our paper provides a public sector performance and efficiency analysis for a time span of 20 years covering 20 countries, with our dataset including many socio-economic areas, which thus make it possible to analyse individual categories of spending areas.

The remainder of the paper is organised as follows. Section 2 provides the literature review, while Sect. 3 describes the methodology applied to compute the performance indicators and the data envelopment analysis methodology. Section 4 report the empirical analysis and Sect. 5 concludes.

2 Literature

Using efficiency analysis, along the lines of the seminal work of Farrell (1957), the related literature expands the use of methods such as Free Disposal Hull (FDH), data envelopment analysis (DEA), and composite performance indicators to study the efficiency of government spending – notably across countries. Coelli et al. (2002) also provide a very useful overview of the methodology at hand.

For example, Afonso and St. Aubyn (2004) computed the efficiency of public spending specifically for the education and health sectors for a sample of OECD countries. These same authors compared both non-parametric methods, namely: Free Disposal Hull (FDH) analysis and data envelopment analysis (DEA) and for both methodologies, they found that in the education sector (input and output), Finland, Japan, Korea and Sweden were the most efficient countries, where their students achieved the best results with fewer resources, whereas Belgium (input) and Portugal (output) were the least efficient. The average input efficiency score for education of the countries under study was 0.89, which means that on average, countries could have used 11% less resources to achieve the same output.

Afonso et al. (2005) carried out one of the first efficiency analyses, using public sector performance (PSP) composite indicators and public sector efficiency (PSE) indicators for 23 OECD industrialised countries for the period of 1990 and 2000. For the countries analysed, the division into small, medium, and large governments corresponded respectively to spending below 40% of GDP, between 40 and 50% of GDP, and above 50% of GDP. The analysis was divided into four expenditure categories, namely: education, health, public infrastructure, and administration. These were called the “Opportunity Indicators”, and are based on the “Musgravian” indicators that reflected allocation, distribution, and stabilisation. The results showed that, on balance, small governments report better economic performance (PSP) than large governments or medium sized governments. The FDH analysis results showed that Japan, United States, and Luxembourg were placed on the “production possibility frontier”, in that large governments, on average, are able to attain the same PSP with 35% less spending. Furthermore, the EU15 countries were identified as being relatively less efficient when compared with both the United States and the average of the other OECD countries in the sample.

Afonso et al. (2010) also studied public sector performance and efficiency for the period of 2001–2003 for 22 countries, including the 12 new EU members at that time, as well as emerging markets, such as Brazil, Chile, Mexico and others. The authors found important differences across the countries, with Brazil being one of the worst countries in terms of PSP. Even though most of the emerging economies performed less well than the old, industrialised countries, the economies of the recently-industrialised Asian countries performed well. Regarding the efficiency scores, the Asian countries achieved higher scores with lower public spending. By analysing the DEA results, Thailand, Cyprus, Ireland, and Korea were found to be on the efficiency frontier, with Chile next on the list. Finally, the Tobit analysis showed that per capita GDP, public sector competence, educational levels, and the security of property rights all appeared to contribute to the prevention of inefficiencies in the public sector.

There are few studies that address public efficiency in Latin America. Clements et al. (2007) calculated the efficiency of spending on infrastructure (rails, roads, electricity, water, and telecommunications) in seven Latin American countries (Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru) during the 1990s and the early 2000s, using the Free Disposal Hull Analysis technique. The results showed that Chile and Mexico demonstrated higher levels of efficiency.

Afonso et al. (2013) analysed 23 countries, using the Public Sector performance (PSP), Public Sector Efficiency (PSE) indicators and data envelopment analysis (DEA) efficiency scores for the period of 2001–2010. These authors divided the countries according to their public spending as a percentage of GDP, namely: below 25% of GD, between 26 and 30% of GDP, and above 30% of GDP. Their results showed again that the larger the size of the government, the less efficient it is. The results of PSP placed Chile, Trinidad and Tobago, Panama, and Costa Rica as the best performers. For education, Costa Rica, Trinidad and Tobago, and Guyana were ranked in first place in that order. In terms of health, Costa Rica and Chile topped the list, while Chile was ranked first for the provision of public infrastructure. Next, the overall PSE score placed Guatemala, Chile, and Peru at the top of the group, followed by the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, and El Salvador. It is also important to remark that Trinidad & Tobago and Panama no not feature at the top of the list of PSE scores. In the DEA Chile, Guatemala and Perú were placed on the efficiency frontier, with, on average, countries being able to achieve the same level of outcome by using 40% less spending, or having the ability to increase their performance by 19% with the same level of inputs.

Ribeiro (2008) also analyses 17 countries of Latin America from 1998 to 2002. Following the same process, the author computed the PSP indicator for five areas: health, education, public administration, equality, and economic performance. Finally, the author computed DEA analysis to gain efficiency scores and analysis the non-discretionary variables, but using the bootstrap methodology. The countries with the best PSP scores were: Chile for health, administration, and economic performance; Costa Rica for education and health, and; Uruguay for equality. The lowest scores in the region were for Guatemala, Paraguay and Bolivia. According to the DEA analysis, the countries located at the efficiency frontier were Costa Rica, the Dominican Republic, and Guatemala. On the contrary, Bolivia, Brazil and Honduras were the more inefficient countries.

Finally, one of the latest studies of efficiency in Latin America is that of Izquierdo et al. (2018), in which the analysis compares countries of Latin America versus OECD countries. The methodology used was DEA for the sectors of health, security, and public administration, employing indicators such as public salaries, transfers and subsidies, and public purchases. These authors estimated on average of approximately 4.4% of inefficiency for GDP, which represents about 16% of public spending. Regarding security, their results showed an average 70% of efficiency, which equates to 30% of crime not being prevented. The results of Izquierdo et al.’s research are diverse across countries, and the authors detected a correlation between better institutions and greater efficiency. In addition, in the health sector, Chile was the only Latin-American country to be placed at the efficiency frontier, while Barbados, Costa Rica, Cuba, and Uruguay also received good efficiency scores. On the other hand, Bolivia, Ecuador, Guatemala, Guyana, Panama and Suriname all registered low efficiency scores for health.

The recent literature has also investigated the relationship between the tax system and spending efficiency, in support of the hypothesis that it is not only changes in revenues that affect the level of public spending. For instance, Afonso et al. (2020) assessed whether structural tax reforms positively or negatively affect public spending efficiency for OECD economies during the period of 2007–2016. They calculated the composite indicators of government performance and then the input efficiency scores for 2016–2017 using DEA technique for 3 different models. The results showed an average efficiency score of around 0.6–0.7, and therefore spending was 30–40% lower, on average. Furthermore, Chile, Korea, and Switzerland were located at the efficiency frontier. Later on, the same authors used a panel analysis to assess the impact of tax reforms on the computed DEA input efficiency scores, reporting that those countries that increased their tax rates experienced lower spending efficiency. When the authors controlled for endogeneity, they achieved two specific results: i) increasing tax rate reforms worsens public sector efficiency, and ii) increasing tax base reforms improves efficiency. Regarding the control variables, the authors found that population, primary balance, and number of internet users all positively affect public sector efficiency.

Following up on this topic, Afonso et al. (2021) evaluated the relevance of taxation for public spending efficiency from 2003 to 2017 for the OECD countries. Having calculating DEA efficiency scores and measuring the impact of tax structures, the main conclusions were that inputs could be theoretically lower by approximately 32–34%, and that expenditure efficiency is negatively associated with taxation.

3 Methodology

3.1 Public sector performance

In total, there are 42 countries in Latin America and the Caribbean, however data are not available for all of them, especially the Caribbean countries. The sources used to collect the information for the social and economic indicators are mainly the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC). From the 42 countries, we analyse 20 countries from both Central (10) and South (10) America for the period of 1990–2019.

Following the methodology of Afonso et al. (2005), we first compute a Public Sector Performance (PSP) composite indicator, which includes seven socio-economic areas of government activity, which are referred to as the PSP sub-indicators (including the Musgravian functions of the State, distribution, economic performance/allocation, and stabilisation), namely:

Administration: is proxied by the Governance indicators of the World Bank, which reflect the perceptions of the quality of public services, capacity to regulate and implement policies and rules of society, freedom of expression, as well as the active participation of society in government. The four indicators used are available for all the countries during the whole period of 1996–2019. The original data ranges from − 2.5 (bad) to 2.5 (good). They were then rescaled from 0 to 5 for the calculation.

Education: is measured by the average years of secondary school enrolment and the quality of the education system over the period of 1990–2019 for the first indicator, and for only 2008–2018 for the second indicator, without information for Belize, Guatemala, and Suriname. The countries with less data available for the whole the period are Guyana, Nicaragua, Paraguay, Honduras, Suriname, Bolivia, and Brazil.

Health: comprises three indicators, two of which have complete data for the whole series since 1990, albeit Maternal Mortality only contains information for all countries since 2000, with data missing before that date for Honduras, Nicaragua, Panama, Suriname, Bolivia, Paraguay, and Peru. These three indicators were: i) Mortality rate, under-5 years old (per 1000 live births): changed to (1000—Value)/1.000; ii) Adolescent fertility rate (births per 1000 women aged 15–19): Changed to (1.000-Value)/1.000; and iii) Maternal mortality ratio (modelled estimate, per 100,000 live births): Changed to (100,000-Value)/100,000.

Infrastructure: is measured by the “Quality of Infrastructure” indicator from the World Economic Forum, with information only being available for the period of 2008–2018, except for Belize, Guyana, and Suriname.

Distribution: includes the Gini Index, although data is missing for several countries during the period, with more fully-available data only being available since 2000. Countries such as Belize, Guatemala, Guyana, Nicaragua, and Suriname lack information. For calculations, the data were changed to the 100-Gini Value.

Economic performance: consists of three indicators: i) unemployment rate; ii) GDP per capita; and iii) GDP growth. The values are a 5-year average, as they are macro indicators that change in the long term. Data are available for all countries.

Stability: is composed of a 5-year average of the coefficient of the variation of growth and the inflation rate. All countries possess information for the whole period. The coefficient of variation of Growth is Standard Deviation (5-year average)/5-year average, which is changed to 1/x and Inflation is the 5-year average (used as 1/x).

For further details on the indicators, see Appendix Table 5. After all the transformations had been carried out, each indicator was then normalised by its sample mean and the resultant values were used to construct the performance composite indicators.

Each PSP sub-indicator is the average of its indicators for each country for every year, with the total PSP being the average of the seven PSP sub-indicators (with equal weights assigned). The first four categories of administration, education, health, and infrastructure are considered to be “Opportunity Indicators”, which combined refer to the government as being the provider of both public services and equal opportunities to the society. The following three categories are distribution, economic performance, and stability, which are called the “Musgravian Indicators”, which represent the ability of the government to promote the functions of distribution, allocation, and stabilisation.

The PSP was computed for the period of 1990–2019, subject to the limitation of the data described above. It is important to mention that the PSP values over time are measured relative to those of other countries, which means that over time the PSP values could increase or decrease, not just because of the evolution of the indicators, but also as a result of the behaviour of the other countries.

3.2 Data envelopment analysis (DEA)

As mentioned by Afonso et al. (2007), this strand of analysis has its roots in the seminal work of Farrell (1957), in which the author provided a measure of productive efficiency which considers inputs and outputs, and went on to obtain a production function with constant returns to scale. Recent papers have used non-parametric approaches for measuring relative expenditure efficiency across countries and this paper follows the description of DEA constructed by Afonso et al. (2007), and thus the measurement of public sector efficiency follows a function for each country i from a total of 20, calculated by:

where \({Y}_{i}\) = Composite indicator representing the output, and \({X}_{i}\) = Government Spending representing input. Accordingly, if country i is efficient, the output is the best that can be obtained for the respective input level.

By using DEA, it is possible to compute a theoretical efficiency frontier, where the inefficiency of country i is measured by computing the distance to the theoretical frontier. The linear programming problem involved supposes k inputs and m outputs for the 20 countries under analysis. For the i-th country, yi is the column vector of the outputs and xi is the column vector of the inputs. X can be defined as the (k × n) input matrix, and Y as the (m × n) output matrix.

The DEA model is then specified for a given i-th country, and, as an illustration, adopting an input-oriented approach, the efficiency scores are computed by means of the following linear programming problem:

where \({{\varvec{y}}}_{{\varvec{i}}}\) is a vector of outputs, \({{\varvec{x}}}_{{\varvec{i}}}\) is a vector of inputs, \({\varvec{\lambda}}\) is a vector of constants, \(1{^{\prime}}\) is a vector of ones, \({\varvec{X}}\) is the input matrix, and \({\varvec{Y}}\) is the output matrix. The efficiency scores of \(\theta\), range from 0 to 1, such that countries performing on the frontier are awarded a score of 1. More specifically, if θ < 1, the country is within the efficiency frontier (i.e., it is inefficient), and if θ = 1, then the country is situated on the frontier (i.e., it is efficient).

DEA can provide two sets of results, both of which are input- and output-oriented. Input efficiency scores represent the proportional reduction in inputs, while the output constant holds firm and the output-oriented scores measure the proportional increase in outputs while the inputs remain constant.Such efficiency scores should be seen as a lower bound indication, since slack may occur. Neverthless, many studies solve the first-stage linear programme for the Farrell technical efficiency measures and then disregard the slacks altogether.

4 Empirical analysis

4.1 Government spending data

Due to the limited availability of data for government spending, our analysis only focusses on the period of 2000 onwards. Over the last two decades government spending in Latin America has shown an upward trend, as presented in Fig. 1. On average, it represented 19.3% of GDP in 2000 and increased to 25.6% of GDP in 2020, with a growth rate of 32.9%. The results also show that government spending in South America is greater than the level in Central America. When comparing the two regions, average spending in 2000 was 20.8% in South America, and 17.0% in Central America, which increased to 26.3% and 25.1% of GDP in 2020 respectively.Footnote 1 However, the growth rate of the percentage of government spending between 2000 and 2020 was greater for Central America (46.9%) when conpared with South America (26.4%). Figure 1 displays the evolution of this indicator, where government spending reached a peak during the years of the global economic crisis in 2008–2009, which was mostly due to the expansive fiscal policies adopted by governments to increase aggregate demand and mitigate the impact of the crisis on the private sector and on households.

Average Government Spending (% GDP). Source Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC). a Belize (since 2012). Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Guyana, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua. Panama, Suriname (since 2013), Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Paraguay, Peru, Uruguay, and Venezuela. b Belize (since 2012), Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Guyana, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Suriname (since 2013). c Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Paraguay, Peru, Uruguay, and Venezuela. *Corresponds to Central Government Spending for all countries, except Peru, where General Government Spending is used

During the years following the crisis, the increase of public spending continued at a good pace, reaching its next peak in 2014. The average growth rate between 2010 and 2014 was 2.6%, while between 2000 and 2009 it was 1.1%, with values showing a slight reduction from 2015 up until 2018, after which it increased again, attaining the highest value of total government spending in 2020, which can be explained by the measures and policies taken by governments to face the economic, social and health crisis caused by Covid-19. It was during 2020 that governments increased spending to completely unexpected rates, with many countries registering values over 17% (El Salvador, Guatemala, Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, and Peru).

This increase of public spending during the period under study was largely due to the commodities prices boom, which started at the beginning of the 2000s and lasted for about a decade, which gave rise to an increase in public revenues. Furthermore, even though these price increases stopped during the months immediately following the economic crisis of 2008–2009, the strong level of Chinese demand soon resumed and prices increased again (Ocampo 2017).

It is important to mention that Latin American countries mostly rely on commodities exports, and therefore government revenues depend on taxes levied on commodity sectors and profits from state-owned enterprises in sectors such as oil and minerals. Latin America is highly natural resource dependent, with countries such as Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, and Venezuela depending mainly on Fuels, whereas Brazil, Chile, Peru are dependent on Minerals and Argentina, Paraguay, Uruguay, Guatemala, Honduras, and Nicaragua depend on Agriculture. According to the analysis of Ocampo (2017), the commodity boom between 2003 and 2013 was stronger for oil and metals than it was for agricultural goods.

4.2 Public sector performance results

Table 1 shows the results of the standardised PSP for 1990, 2000, 2010, and also 2019 for the 20 countries under analysis. These results represent outcome indicators, without considering the amount of spending incurred. Panama registered the highest total PSP in 1990 and 2000 (2.23 and 1.43 respectively) compared with Guyana (0.42) in 1990, and both Venezuela and Ecuador in 2000 (which registered almost the same value of 0.74), which recorded the lowest PSP during the same years. Later, in 2010, the first place was passed on to Chile, which registered the highest score (1.24) between the countries and maintained this position for many years, up until 2013, whereas the worst place was occupied by Nicaragua, which recorded 0.78. Next, the best and worst ranked performers changed back to Panama (1.36) and Venezuela (− 0.5) in 2019.

Analysing by type of indicator, i.e., whether it is Musgravian or Opportunity PSP, the results show that best or worst scores do not represent the same countries as in the cases of Total PSP. For example, if only Musgravian PSP (economic indicators) are checked, then the best country was Bolivia (1.43) in 2010 and the worst country was Nicaragua in both 1990 and 2010. In addition, the same occurred with Opportunity PSP (social indicators), where Uruguay was the best-ranked in 1990 (1.22), in 2000 and 2010 it was Chile, and in 2019 it was Costa Rica. On the contrary, Paraguay and Guatemala registered the lowest results in 1990 and 2000.

By ranking, if we consider the first and last three positions during the period of 1990–2019, the best country for many years are Panama, Chile, and Belize, while the worst scores are Venezuela, Nicaragua, and Paraguay.

Figure 2 shows the evolution of the PSP indicator of the best performers, with scores ranging from 0.94 to 2.23. During the first decade, Panama was the best performer, however the three countries registered a decrease in their PSP. On the contrary, Belize started to improve in 1998, which is probably because the indicator fell this year during a period of economic crisis in most of the countries and inflation values were very high. Accordingly, when comparing among the countries under analysis, Belize was among the countries with a lower inflation rate, which helped to improve its PSP. Chile demonstrates the most constant pattern during the whole period.

On the other hand, the three weakest PSP performers in the sample are Venezuela, Nicaragua, and Paraguay (Fig. 3), as shown by scores ranging from 0.43 to 1.08, except during 2019 and 2020, when Venezuela registered a negative PSP value in 2019 (as a result of the consequence of negative GDP growth rates). None of the countries appears to have improved, at least not along the period under study, with all remaining within the same range.

Analysing PSP by the areas and for each 10 years, as shown in Fig. 4, Uruguay led the group of countries in education, however Costa Rica took the first place in 2000, and later in 2010 and 2019. The worst country in Latin America in 2000 was Guatemala, while Paraguay was in 2010, and Guatemala was again the worst country in 2019. Moving to the results for Health, the first-placed country for the same 3 years was Chile, with the worst-ranked country being respectively Guatemala (2000), Guyana (2010), and Venezuela (2019). For Administration, Chile once again led the ranking for the 3 years in question, with the worst performers being Paraguay and Venezuela.

Contrary to Economic PSP, Belize was the best performer in 1990, Mexico in 2000, and lately on Panama occupied this place in 2010 and 2019. The worst-performing countries were Guyana in 1990, Ecuador in 2000, Belize in 2010, and Venezuela in 2019. In terms of the stability indicators, Panama is also highlighted in 1990 and 2000, with Bolivia being ranked in first place in 2010, and in 2019 this place changed to El Salvador. On the other hand, Peru was placed at the bottom of the ranking in 1990 for Stability, followed by Venezuela in 2000 and 2010, while Suriname was ranked with the worst result for this factor in 2019.

4.3 DEA efficiency scores

Three models each using different inputs were used for the application of the DEA methodology, applying both input-oriented and output-oriented approaches.

The first model uses Total Public Spending as percentage of GDP as the input and Total PSP Scores as the output, while Table 2 report the results (for the years 2009, 2013, and 2019).

The efficient countries located on the production possibility frontier in 2009 are Guatemala, Panama, Chile, and Paraguay. In the input-oriented approach, Guatemala, Panama, and Paraguay are peers for themselves and are efficient, while Chile has as a reference country Panama and a slack of 5.10 (weakly efficient), meaning that Chile could have reduced 5.10 units of spending and reach the same levels of Panama. Interestingly, in the output-oriented approach, the four countries are strongly efficient and have zero slacks. For instance, Bolivia which is in the last position, with an efficiency score of 0.44, has as peers Guatemala and Panama, with a weight of 0.80 and 0.20 respectively. Analysing the slacks, Uruguay obtained the highest value after Chile. Uruguay has an efficient score of 0.91 and 2.63 points of slack, meaning that it could have reduced the input 2.63 times after 9%.

Guatemala and Chile remain in the same ranking in 2013 and both have a strongly efficient input and output approach. In the output-oriented model, almost all countries have slacks, with Suriname having the highest value of 13.19 units, with an efficient score of 0.85%, its reference country being only Chile.

Interestingly, another country emerged at the top of the ranking in 2019, which is El Salvador, together again with Guatemala. However, in the output model, El Salvador is weakly efficient, even though it has an efficient score of 1, it obtained a slack of 3.46 points. In addition, in the same year Chile dropped to 11th position, and thus 2019 was obviously not a good year for Chile. Analysing in depth, Chile could have used 42% less of input and has as its peers El Salvador (10%) and Guatemala (90%). It is important to conclude that in Model 1, Guatemala was the only efficient country during the whole period of 19 years, and therefore is the reference country for many countries in both output and input-oriented models.

Analysing the differences in the results according to the method used (input–output), most countries remain in the same position, or close to it. In particular, there are some countries, such as Bolivia or Nicaragua, that demonstrate a large difference in the results. Nicaragua is more efficient in terms of inputs and is ranked in the Top 10, however, when considered in terms of output, it is ranked among the last positions, and is thus one of the worst countries. Bolivia is the opposite, as the inputs results show zero efficiency, albeit this result improves for outputs. It is important to mention that Bolivia has one of the highest percentages of public spending (over 30%), and that Nicaragua belongs to the group of countries that spend less than 20%.

Assuming variable returns to scale and considering an input-oriented approach (how much input quantities can be proportionally reduced without changing the output quantities produced), DEA displayed the results described below.

Using available data from 17 of the 20 countries, the average input efficiency score in 2000 was 80%, which implies that countries could achieve the same level of PSP by using 20% less government spending. The countries situated on the production possibility frontier are Guatemala and Panama, with Mexico and Argentina ranked after them, while the countries ranked in the last positions are Brazil, Venezuela, and Bolivia, which means that they are located the furthest from the efficiency frontier. A summary of efficiency scores is reported in Appendix A (the detailed results per year are described in the Online Appendix).

During the period under analysis, the most efficient countries are Guatemala, Panama, Chile, and Paraguay. This contrasts with the previously-obtained PSP results, where Panama and Chile are also ranked as the best performers, although, interestingly, Paraguay is not in this group, as it was ranked the worst in the PSP results. On analysing the data for Paraguay, it can be seen that its efficiency score is high as a result of the low values of government spending as a percentage of GDP when compared with the other countries.

Regarding the results of the output-oriented approach (i.e., how much output quantities can be proportionally increased without changing the input quantities used), the same 17 countries had an output efficiency score on average of 73% in 2000, implying that countries could have increased their performance by 27% with the same level of inputs. The countries located on the production possibility frontier were once again Guatemala and Panamá, followed by Mexico and Chile in third and fourth place respectively. The worst-performing countries were Venezuela, Brazil, and Peru.

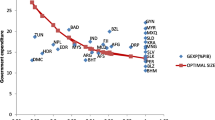

Figure 5 illustrates the efficiency frontier for Model 1 (with one input and one output) over a period of 4 years. The efficient countries in 2000 are Guatemala and Panama, with Mexico lying very close. The efficient countries in 2009 are Guatemala, Panama, Chile, and Paraguay while the efficient countries in 2013 are Guatemala and Chile. Finally, in 2019, the efficient countries are El Salvador and Guatemala.

We also assessed the level of efficiency by using two alternatives specifications. First, we used Public Spending on Health (% of GDP) as the input and Health PSP as the output (Model 2): this was mostly on account of the health crisis due to Covid-19 and also in order to gain a view of this sector before this pandemic. Second, Model 3 uses Total Public Spending (% of GDP) as the input and the Economic component of the PSP as the output. The efficiency score results are reported in Tables 3, and 4, respectively (for 2009, 2013, and 2019).

From Table 3 we can observe that the input efficiency score increases from 33% in 2009 to 48% in 2013, which is the highest score, and then it starts to decrease until 2019, with 41%. The best year for the health sector appears to have been 2013, during which the increase of public spending was able to achieve better efficiency results.

In contrast, the output-oriented score is 99% for the 3 years, where there are proportional changes in terms of public spending, although these did not affect the level of efficiency and neither is there enough space for efficiency improvement.

Over the 3 years, the results show that Costa Rica is the only efficient country and is the reference country for all the others. However, the results present slacks in the output for all the countries, except Costa Rica and Chile, meaning that all the countries could have reduced even more the input and get output close to that of Costa Rica.

For the output-oriented approach, the peers are Costa Rica and Chile. Both are efficient and reference countries for themselves. For instance, in 2009 Guyana is the least efficient country (97%) and its peers are Costa Rica and Chile with weights of 0.54 and 0.43. In 2013, Nicaragua was the least efficient, and its peers are Costa Rica (0.24) and Chile (0.73). In 2019, Guyana and Nicaragua continue to be inefficient and the peers are Costa Rica (0.45; 0.36) and Chile (0.52; 0.62), respectively.

In the case of Chile, it is interesting to see that while in the output-oriented approach it is the most efficient country, it is not in the input-oriented category. This is because Chile is the country with the highest percentage of Public Spending in Health on average, with government spending being 3.53% of GDP during the period under analysis and it registered a significant increase over the years, e.g., its growth rate is 92% from 2000 to 2019. It is only when analysing output that Chile obtains the best score, however when both input and output are contrasted and compared between other countries, DEA estimates highlight the efficiency of Costa Rica. The level of public spending in Costa Rica is on average 0.61% of GDP, which represents a vast difference from Chile. In terms of output, Costa Rica is ranked in second and third place, and, as a result, DEA methodology punishes Chile and it is calculated that in 2009 it could have obtained the same PSP results by using 87% less spending, and that in 2013 it could have used 78% less, while in 2019 it could have used 85% less on government spending. The overall conclusion is that Chile is not an efficient country in the health sector, and that it has considerable scope for improvement.

In Table 4, which show the assessment for economic performance, it can be seen that countries could have achieved the same average level of PSP by using 32% less on government spending, and that countries could have increased their PSP by 24%, while using the same levels of spending. Furthermore, these scores worsen for 2019, during which countries could achieve the same level of PSP by using 39% less government spending, or countries could have increased their PSP by 38% by maintaining the same levels of spending. Economically-speaking, 2019 is the less-efficient year across all the countries.

See the Appendices for a summary of the main results of the three models for both input-and output-oriented efficiency scores and also the complete data set for 2000–2019.

In 2009, the input-oriented approach presents three peers: Guatemala, Panama and Paraguay, which are efficient and peers for themselves. Costa Rica, with a efficiency score of 84%, has as peers Guatemala (0.81) and Paraguay (0.19). On the other hand, Bolivia with 38% has as peers Guatemala (0.48) and Paraguay (0.51). The output-oriented approach has only Guatemala as a reference country for all the countries.

In 2013, the input-oriented approach presents two peers: Guatemala and Panama, which are efficient and peers for themselves. Guatemala is also the peer for the majority of the countries. Nicaragua with a efficiency score of 82%, has as only Guatemala as its peer. On the other hand, Bolivia with 51% has as its peers Guatemala (0.35) and Panama (0.64). The output-oriented approach has only Panama as a peer for all the countries.

In 2019, the esults show one peer for both input- and output-oriented approach, which is Guatemala. In the output model, all countries present slacks, for example, Paraguay could have produced 23% more with the same input plus 2.40 units and Belize could have produced 52% more with the same input plus 10.7 units. Suriname could have produced 63% more with the same input plus 9.9 units.

5 Conclusion

On average, governments in Latin America spent about 25.6% of GDP on the provision of public goods, services, and transfers in 2020. Furthermore, the available statistics reflect a vast increment in public spending for the last years of the study period (2013 and 2019), with an average growth rate of 32.9%. During periods of recession, such as the economic crisis of 2008–2009 or the health and economic crisis of 2019, governments tend to spend more on public expenditures. This paper aims to calculate how efficient public spending has been over the last 20 years.

By collecting indicators for different areas of government activities for all countries in Latin America, the biggest challenge was to find comparable measures for all the countries and a complete data set for every year, and consequently the final sample analysed is for 10 countries in South America, and 10 from Central America for the period of 2000–2019. Once the indicators were determined, transformations were applied to each with the aim to obtain the same scales and then normalise them. The next phase was to calculate the “Public Sector Performance (PSP)” composite indicator, in order to obtain a comparable and unique measure that represents the outcome for all the countries in the overall sample. Finally, data envelopment analysis technique was applied to compute efficiency scores and rankings for each year.

With regards the original indicator of “Public Spending as a percentage of GDP”, figures show that health, education, and social protection are key areas of spending, albeit within the group of countries the level of spending differs, while in the South American region, the highest spending is on social protection, whereas in Central America it is on education.

From the analysis of the PSP indicator, those countries that performed better during the period of 1990–2019 are Panama, Chile, and Belize. Interestingly, these three countries are diverse in their level of public spending, while Belize is situated in the group that spend over 30% of GDP, while Chile belongs to the group that spend between 20 and 30% of GDP, and Panama is within the group that spend less than 20% of GDP. On the other hand, the worse-performing performance countries are Venezuela, Nicaragua, and Paraguay, where the public spending of Nicaragua and Paraguay is less than 20% of GDP and Venezuela spends between 20 and 30% of GDP.

Furthermore, the DEA results show a degree of diversity between the countries, but commonly there is potential for increase efficiency in public spending. Three models were applied for each year: i) a general model, using Total Public Spending (% GDP) as the input and Total PSP as the output; ii) Model 2, which uses Health PSP as the output and Public Spending on Health as the input; and iii) Model 3, with Economic PSP as the output and Total Public Spending as the input.

With respect to Model 1, assuming variable returns to scale and adopting both the input and output approach, the set of countries that define the theoretical production possibility frontier in 2019 are El Salvador and Guatemala. The average input score during the period of 2000 to 2019 decreased from 80% in 2000 to 65% in 2019 (when countries could have used 35% less spending to achieve the same levels of PSP). On the contrary, using the output-oriented approach, the efficiency scores slightly increased from 73% in 2000 to 78% in 2019 (when countries could have increased their performance by 22% with the same level of inputs). We also report the country peers for each analysis, which can provide some policy recommendations for the atuhrorities. For instance, Bolivia which is labelled as less efficient, with an efficiency score of 0.44, has as peers Guatemala and Panama with a weight of 0.80 and 0.20 respectively. Hence, trying to converge to some combination of these countres would be useful.

Analysing the years of the global economic crisis of 2008–2009, scores in both approaches are worse, suggesting that when Latin American countries passed through crises and increased the public spending, their efficiency decreased, with 2019 recording an emphasised decrease.

The least efficient countries differ in their approaches, with Suriname, Brazil, and Belize being at the bottom of the ranking in 2019 for the input approach. It should be noticed that Belize was among the best performers in PSP, but when this is compared with spending incurred, it is not efficient, representing a case that shows the importance of applying DEA methodology to describe efficiency. In addition, in terms of output approach, the worst countries are Nicaragua, Suriname, and Brazil.

Model 2 gave rise to interesting findings, in that the average input efficiency score during the period is 40%, which is a very low score, indicating that countries could have used 60% less spending on health to attain the same outcomes if they had been fully efficient. On the other hand, the average output score is surprisingly high, with an average of 99%, suggesting that the countries under study almost attained the maximum possible return from most of the outputs with the level of spending in the health area. From the point-of-view of the input-oriented approach, the best country for health is Costa Rica, which remain fully efficient over the period under analysis, with Chile positioned at the bottom of the ranking.

Finally, the results of Model 3 led to an average input efficiency score of 68% from 2000 to 2019, with those countries that could have achieved the same level of PSP using 32% less government spending. In contrast, the average output efficiency score is 66%, implying that countries could have increased their performance by 34% with the same level of inputs. Accordingly, governments have a large space for improvement in economic areas.

Surprisingly, the findings from Model 3 suggest that the lower the spending ratios, the more efficient are the countries. Guatemala, Panama, and Paraguay rank as the best performers in both the input- and output-oriented approach, all of which are countries with a public expenditure as a % of GDP of less than 20%.

To conclude, the analysis of the three models provides an important understanding of the differences between countries when analysing public spending in general vs in particular areas, such as health or Total PSP (which aggregates many fields) vs. Economic or Health PSP. For example, Chile, which topped the ranking for many years of the more efficient countries in Model 1, does not do so when only health or economic areas are analysed. The results divided by individual spending areas seem to present a more promising approach for measuring efficiency and effectiveness on a cross-country basis.

Future research can continue this analysis with the application of appropriate methodologies to better understand the determinants of the efficiency scores already calculated, and, in addition, they could identify what governments can do to achieve greater efficiency. Advances also need to be made regarding, for instance, the effects of taxation on the efficiency scores as manifested in the literature review. In addition, in order to make the most use of the large cross-country panel dataset presented in this study, in future work it would be interesting to apply alternative DEA models, such as the DEA-Windows method, which would enable a year-to-year comparison of the results and help contrast the existing scores obtained for each year, or compute Malmquist indicators.

Notes

No data is available for Panama (2018, 2019, and 2020), Bolivia (2019 and 2020) and Venezuela (2015 to 2020).

References

Afonso A, Aubyn M (2004) Non-parametric approaches to education and health efficiency in OECD countries. J Appl Econ 8(2):227–246

Afonso A, Schuknecht L, Tanzi V (2005) Public sector efficiency: an international comparison. Public Choice 123:321–347

Afonso A, Schuknecht L, Tanzi V (2007) Public sector efficiency: evidence for new eu member states and emerging markets. Appl Econ 42(17):34

Afonso A, Schuknecht L, Tanzi V (2010) Public sector efficiency: evidence for new EU member states and emerging markets. Appl Econ 42(17):2147–2164

Afonso A, Jalles JT, Venâncio A (2021) Taxation and public spending efficiency: an international comparison. Compar Econ Stud 63:356–383

Afonso A, Romero A, Monsalve E (2013) Public sector efficiency: evidence for Latin America. Inter-American Development Bank IDB-DP-279.

Afonso A, Tovar Jalles J, Venâncio A (2020) Structural tax reforms and public spending efficiency. REM Res Econ Math 20

Clements B, Faircloth C, Verhoeven M (2007) Public spending in Latin America: trends and key policy issues. Int Monetary Fund 07(21):34

Coelli T, Rao D, Battese G (2002) An introduction to efficiency and productivity analysis, 6th edn. Massachusetts, Kluwer Academic Publishers

Farrell M (1957) The measurement of productive efficiency. J Roy Stat Soc 120(3):39

Gnangoin YTB, Edjoukou AJR, Kassi DDF (2019) Public spending and economic growth in Latin America countries: a panel fixed effect analysis. Int J Bus Econ Sci Appl Res 12:50–63

Izquierdo A, Pessino C, Vuletin G (eds) (2018) Better spending for better lives. How Latin America and the Caribbean can do more with less. Inter-American Development Bank

Ocampo JA (2017) Commodity-led development in Latin America. In: Alternative pathways to sustainable development: lessons from Latin America, edited by by Gilles Carbonnier et al.. s.l.:s.n

Podestá A (2020) Gasto público para impulsar el desarrollo económico e inclusivo y lograr los Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible. Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe (CEPAL), serie Macroeconomía del Desarrollo(214 (LC/TS.2020/123))

Ribeiro MB (2008) Eficiência do gasto público na América Latina: uma análise comparativa a partir do modelo semi-paramétrico com estimativa em dois estágios. Issue Serie Gestión Pública No 67:37

Acknowledgements

We thank an anonymous referee for very useful suggestions. This research was supported by the Portuguese Science Foundation, FCT (Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia) [Grant Number UIDB/05069/2020]. The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the authors’ employers. Any remaining errors are the authors’ sole responsibility.

Funding

Open access funding provided by FCT|FCCN (b-on).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Responsible Editor: Jesus Crespo Cuaresma.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Afonso, A., Fraga, G.B. Government spending efficiency in Latin America. Empirica 51, 127–160 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10663-023-09599-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10663-023-09599-4