Abstract

Previous studies that assessed the impact of exchange rate volatility on Turkey’s trade flows, assumed that the effects are symmetric. We change that assumption by assessing the possibility of asymmetric effects of the real lira-euro GARCH-based volatility on trade flows of 62 2-digit industries that trade between Turkey and EU. Like previous research when we assumed symmetric effects and estimated a linear model for each industry, we found short-run effects of volatility on 26 Turkish exporting industries to EU and on 40 EU exporting industries to Turkey. These short-run effects lasted into the long run only in 11 Turkish and 19 EU exporting industries. However, when we estimated a nonlinear model, we found short-run asymmetric effects of volatility on 38 Turkish and 49 EU exporting industries. Short-run asymmetric effects translated into long-run asymmetric effects in 19 industries in both groups.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

It should be recognized that two other studies used industry level data from Turkey and estimated panel models. While Solakoglu et al. (2008) found no significant link between exchange rate volatility and Turkish exports, Alper (2017) found positive effects with some partners and negative effects with some others. Since both studies used panel models, again, they suffer from aggregation bias in that one industry’s response to volatility could be different than the other’s. None of these studies considered the possibility of asymmetric response as we do in this paper.

Note that the effects of economic activities on trade flows could be negative if increased activity is due to an increase in production of import-substitute goods (Bahmani-Oskooee 1986).

Note that Bahmani-Oskooee and Ghodsi (2018) and Bahmani-Oskooee (2019) has demonstrated that the t-test here is the same as the t-test applied to judge significance of lagged error-correction term in the Engle and Granger (1987) approach due to Banerjee et al. (1998). Note also that estimates of θ0 and \( \rho_{0} \) must also be negative.

Indeed, variables could be combination of I(0) and I(1). Since these are properties of almost all macro variables, there is really no need for pre-unit-root testing. This is another advantage of this approach. However, by applying the ADF test we made sure that we have no I(2) variable.

Additional diagnostics included in Table 3 are the LM test for serial correlation and Ramsey’s RESET test for misspecification. Both are insignificant in most models. Furthermore, stability of estimates is confirmed at least either by the CUSUM or by CUSUMSQ test, indicated by “S” for stable estimates and “US” for unstable estimates. Adjusted R2 is also reported to judge the goodness of the fit in each model.

By meaningful we mean the estimates are supported by at least one of the tests for cointegration that are provided in diagnostics Table 6.

Other diagnostics statistics are similar to those in Table 3 and need no repeat here.

While the short-run effects are asymmetric in most industries, short-run cumulative or impact asymmetric effects are verified by the Wald-S test (reported in Table 14) only in 10 industries coded as 0, 5, 11, 29, 51, 52, 54, 55, 78, and 82.

Other diagnostics in Table 14 are similar to those in Table 10 and need no repeat. Note also that in the early years of our study period, i.e., 2001 Turkey faced a financial crisis which led the Turkey to enter into a stand-by agreement with IMF to manage its exchange rates. A political crisis also took place in 2017. These crises do not seem to have strong impact on our estimates since the CUSUM stability test confirms stable estimates in almost all industries.

References

Aftab M, Syed KBS, Katper NA (2017) Exchange-rate volatility and Malaysian–Thai bilateral industry trade flows. J Econ Stud 44:99–114

Alper AE (2017) Exchange rate volatility and trade flows. Fiscaoeconomia 1:14–39

Al-Shayeb A, Hatemi-J A (2016) Trade openness and economic development in the UAE: an asymmetric approach. J Econ Stud 43:587–597

Altintas H, Cetin R, Oz B (2011) The impact of exchange rate volatility on Turkish exports: 1993–2009. South East Eur J Econ Bus 6:71–81

Arize AC, Osang T, Slottje DJ (2000) Exchange-rate volatility and foreign trade: evidence from thirteen LDCs. J Bus Econ Stat 18:10–17

Arize AC, Malindretos J, Igwe EU (2017) Do exchange rate changes improve the trade balance: an asymmetric nonlinear cointegration approach. Int Rev Econ Finance 49:313–326

Asteriou D, Masatci K, Pilbeam K (2016) Exchange rate volatility and international trade: international evidence from the MINT countries. Econ Model 58:133–140

Baghestani H, Kherfi S (2015) An error-correction modeling of US consumer spending: are there asymmetries? J Econ Stud 42:1078–1094

Bahmani-Oskooee M (1986) Determinants of international trade flows: case of developing countries. J Dev Econ 20:107–123

Bahmani-Oskooee M (2019) The J-curve and the effects of exchange rate changes on the trade balance. In: Rivera-Batiz FL (eds) International money and finance, volume 3. Encyclopedia of International Economics and Global Trade, World Scientific Publishing Co., Singapore, chapter 16, forthcoming 2019

Bahmani-Oskooee M, Aftab M (2017) On the asymmetric effects of exchange rate volatility on trade flows: new evidence from US-Malaysia trade at industry level. Econ Model 63:86–103

Bahmani-Oskooee M, Fariditavana H (2016) Nonlinear ARDL approach and the J-curve phenomenon. Open Econ Rev 27:51–70

Bahmani-Oskooee M, Ghodsi H (2018) On the link between housing market and stock market: evidence from OECD using asymmetry analysis. Int Real Estate Rev 21:447–471

Bahmani-Oskooee M, Hegerty SW (2007) Exchange rate volatility and trade flows: a review article. J Econ Stud 34:211–255

Bahmani-Oskooee M, Hegerty SW (2009) The effects of exchange-rate volatility on commodity trade between the U.S. and Mexico. South Econ J 75:1019–1044

Bahmani-Oskooee M, Nouira R (2020) On the impact of exchange rate volatility on Tunisia’s trade with 16 partners: an asymmetry analysis. Econ Change Restruct (forthcoming)

Banerjee A, Dolado J, Mestre R (1998) Error-correction mechanism tests in a single equation framework. J Time Ser Anal 19:267–285

Belke A, Goecke M (2005) Real options effects on employment: does exchange rate uncertainty matter for aggregation? Germ Econ Rev 6:185–203

Belke A, Gros D (2001) Real impacts of intra-European exchange rate variability: a case for EMU? Open Econ Rev 12:231–264

Belke A, Gros D (2002) Designing EU–US monetary relations: the impact of exchange rate variability on labor markets on both sides of the Atlantic. World Econ 25:789–813

Caballero RJ, Corbo V (1989) The effect of real exchange rate uncertainty on exports. World Bank Econ Rev 3:263–278

De Grauwe P (1988) Exchange rate variability and the slowdown in growth of international trade. IMF Staff Pap 35(1):63–84

Demez S, Ustaoglu M (2012) Exchange rate volatility’s impact on Turkey’s exports: an empirical analyze for 1992–2010. Procedia Soc Behav Sci 41:168–176

Demirhan E, Demirhan B (2015) The dynamic effect of exchange rate volatility on Turkish exports: parsimonious error-correction model approach. Panoeconomicus 62:429–451

Denaux ZS, Falks R (2013) Exchange rate volatility and trade flows: the EU and Turkey. Southwest Econ Rev 40:113–121

Doganlar M (2002) Estimating the impact of exchange rate volatility on exports: evidence from Asian countries. Appl Econ Lett 9:859–863

Durmaz N (2015) Industry level J-curve in Turkey. J Econ Stud 42:689–706

Engle RF, Granger CWJ (1987) Cointegration and error correction: representation, estimation, and testing. Econometrica 55:251–276

Gogas P, Pragidis I (2015) Are there asymmetries in fiscal policy shocks? J Econ Stud 42:303–321

Gregoriou A (2017) Modelling non-linear behavior of block price deviations when trades are executed outside the bid-ask quotes. J Econ Stud 44:206–213

Halicioglu F (2007) The J-curve dynamics of turkish bilateral trade: a cointegration approach. J Econ Stud 34:103–119

Halicioglu F (2008) The bilateral J-curve: turkey versus her 13 trading partners. J Asian Econ 19(3):236–243

Kasman A, Kasman S (2005) Exchange rate uncertainty in Turkey and its impact on export volume. METU Stud Dev 32:41–58

Kisswani KM, Nusair SA (2014) Nonlinear convergence in Asian interest and inflation rates. Econ Change Restruct 47:155–186

Lima L, Foffano Vasconcelos C, Simão J, de Mendonça H (2016) The quantitative easing effect on the stock market of the USA, the UK and Japan: an ARDL approach for the crisis period. J Econ Stud 43:1006–1021

Nusair SA (2012) Nonlinear adjustment of Asian real exchange rates. Econ Change Restruct 45:221–246

Nusair SA (2016) The J-curve phenomenon in European transition economies: a nonlinear ARDL approach. Int Rev Appl Econ 31:1–27

Ozturk I, Kalyoncu H (2009) Exchange rate volatility and trade: an empirical investigation from cross-country comparison. Afr Dev Rev 21:499–513

Peree E, Steinherr A (1989) Exchange rate uncertainty and foreign trade. Eur Econ Rev 33(6):1241–1264

Pesaran MH, Shin Y, Smith RJ (2001) Bounds testing approaches to the analysis of level relationships. J Appl Econom 16:289–326

Shin Y, Yu B, Greenwood-Nimmo M (2014) Modelling asymmetric cointegration and dynamic multipliers in a nonlinear ARDL framework. Festschrift in Honor of Peter Schmidt. Springer, New York, pp 281–314

Solakoglu MN, Solakoglu EG, Demirag T (2008) Exchange rate volatility and exports: a firm level analysis. Appl Econ 40:921–929

Tatliyer M, Yigit F (2016) Does exchange rate volatility really influence foreign trade? Evidence from Turkey. Int J Econ Finance 8:33–38

Vergil H (2002) Exchange rate volatility in Turkey and its effects on trade flows. J Econ Soc Res 4:83–99

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Valuable comments of two anonymous referees are greatly appreciated. Remaining errors, however, are our own.

Appendix: Data definitions and sources

Appendix: Data definitions and sources

Monthly data covering the period January 1997–December 2018 are used to estimate all models. The data come from the following sources:

-

A.

TurkStat (Turkish Statistical Institute).

-

B.

International Financial Statistics of the IMF.

-

C.

Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey (CBRT).

1.1 Variables

\( X_{i}^{TR} \) = Volume of exports of commodity i by Turkey to EU. In the absence of export prices at commodity level, we follow Bahmani-Oskooee and Hegerty (2009) and use aggregate export price index of Turkey to deflate the nominal exports of each commodity. Data come from source A.

\( M_{i}^{TR} \) = Volume of imports of commodity i by Turkey from EU. Again, we use aggregate import price index of Turkey to deflate the nominal imports of each commodity. Data come from source A.

IPEU = Measure of EU economic activity. Since data are monthly, we follow Bahmani-Oskooee and Aftab (2017) and use Industrial Production Index which is available on a monthly basis from source B.

IPTR = Measure of Turkey’s economic activity, also proxied by the industrial production index from source B.

REX = Real bilateral exchange rate between Lira and euro. It is defined as, (NEX*CPIEU)/CPITR where NEXi is the nominal exchange rate defined as number of Lira per euro, CPIEU is the price level in the euro zone and CPITR is the price level in Turkey. Thus, an increase in REX reflects a real depreciation of the Turkish lira. All data come from Source C.

Vt = Volatility measure of REXt based on Generalized Autoregressive Conditional Heteroskedasticity (GARCH 1, 1). Following Bahmani-Oskooee and Aftab (2017) we assume that our variable REX is random and it follows a first order auto-regressive process, i.e., REXt = σ0 + σ1 REXt−1 + εt, where εt is white noise with E(ε) = 0 and V(ε) = h2. In order to forecast the variance of REX, the conditional variance of εt which is a time varying variable needs to be estimated.

The following theoretical specification of a GARCH model is used here:

where h 2t is the conditional variance. The GARCH (p,q) model outlined by Eq. (9) is used to generate the predicted value of h 2t as a measure of the volatility of real exchange rate. Equations (8) and (9) are estimated simultaneously after establishing an ARCH effect.

The order of GARCH is determined by significance of α’s and χ’s in (9). In our case like many other studies, a GARCH (1,1) specification is sufficient. The exact results with the t-ratios inside the parentheses are as follows:

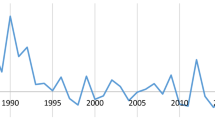

In order to gain some insight to our measure of volatility, we plot it in Fig. 1.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bahmani-Oskooee, M., Durmaz, N. Exchange rate volatility and Turkey–EU commodity trade: an asymmetry analysis. Empirica 48, 429–482 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10663-020-09472-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10663-020-09472-8