Abstract

We analyse the correlation of various measures of social capital with the willingness to migrate in 28 post-communist and five western European comparison countries using the Life in Transition Survey. Memberships in clubs and civil society organisations are substantially lower in post-communist countries that in the Western European countries this is mainly due to the cohorts socialised prior to political reforms in the 1990’s. Differences in endowments with this measure of social capital explain around 2.5 percentage points of the 9–11 percentage point difference in the willingness to migrate between the post-communist and comparison countries. Differences in contacts to friends and family, by contrast, contribute only little to explaining these differences. Furthermore, despite clear cohort effects in endowments with social capital between cohorts socialized during and after communist rule, there is no clear evidence of such cohort effects in the impact of social capital on the willingness to migrate.

Source: LiTS, own calculations

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Such measures have been used extensively in the migration literature (see Van Dalen and Henkens 2008 for a survey and Bönisch and Schneider 2013 for an application to the impact of social capital). This is justified by the few observations on actual migration provided in most data sets (in the low mobility context of post-communist countries – see Huber and Nowotny 2016) and by such data having been shown to capture the determinants of actual migration behavior rather precisely (see Van Dalen and Henkens 2008).

This has previously been used by Broulíková et al. (2018), Cojocaru (2014) and Nikolova and Sanfey (2016). We focus its’ second wave because the first and third waves (from 2006 to 2016) contain no or incomparable questions on the dependent and most of the independent variables used in the current analysis.

The wording of the questions on and coding of the key dependent and independent variables is explained in more detail in the data “Annex” to this paper.

The LITS also contains a question on whether respondents plan to move abroad or (if not wanting to move abroad) within the country in the next year. This question, however, does not allow for a separate analysis of the willingness to move abroad and within the country because only those unwilling to migrate abroad are asked about their willingness’ to migrate internally. It also does not allow a separate analysis for different cohorts on the account of the few affirmative responses to this question. In robustness checks (available from the authors) we, however, also ran the baseline specification for this alternative dependent variable. These results are less robust than those in the current analysis and are also often statistically insignificant. Results for the memberships in clubs and civil society organisations are robust, however.

In robustness checks we also included these as dichotomous rather than continuous variables. The results are driven by the extreme values of these variables. People that meet their friends on most days are significantly more likely to be willing to migrate, as are people who rarely or never meet their family. The results for other variables are not affected by this change in specification, though.

This was encoded by 10 categorical variables (in 5-year age groups from 16 to 64 years) to account for potential non-linearities.

Further robustness checks (available from the authors) included running regressions where country fixed effects were replaced by region fixed effects (to account for the regional context), excluding the years of residence from the specification and adding indicator variables for urban and rural regions. None of these changes altered the qualitative results for the aggregate willingness to migrate.

These are the CEE-EU countries and the Balkan countries (Albania, Bosnia, Croatia, Macedonia, Montenegro, Kosovo, Serbia, and Slovenia) and the FSU countries (Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Mongolia, Moldova, Russia, Tajikistan, Ukraine, Uzbekistan). We exclude Turkey from the analysis as it is somewhat of a special case given that the other comparison countries are EU members.

We exclude persons in late childhood and early adulthood (i.e. aged between 6 and 19 years) in 1990 to avoid including age groups that have been shown to have rather unstable attitudes in previous literature (see e.g. Alwin and Krosnick, 1991). In our robustness checks (available from the authors) we, however, also provide regression results for those aged older than 26 and younger than 40.

Results with respect to membership in clubs and civil society organisation are also robust to instrumentation with the respective regional shares of social capital (see Table 6 in the appendix). Otherwise in IV-results the frequency of meeting friends as well as the frequency of meeting the family is an insignificant determinant of all measures of the willingness to migrate in CEE-EU and the comparison countries. In all post-communist countries, however, the frequency of meeting friends statistically significantly reduces the willingness to migrate, and the frequency of meeting the family increases it.

References

Alwin DF, Krosnick JA (1991) The reliability of survey attitude measurement: the influence of question and respondent attributes. Sociol Methods Res 20(1):139–181

Andrienko Y, Guriev S (2004) Determinants of interregional mobility in Russia. Econ Transit 12(1):1–27

Bähr S, Abraham M (2016) The role of social capital in the job-related regional mobility decisions of unemployed individuals. Social Netw 46:44–59

Becker SO, Boeckh K, Hainz C, Woessmann L (2016) The empire is dead, long live the empire! Long-run persistence of trust and corruption in the bureaucracy. Econ J 126(590):40–74

Belot M, Ermisch J (2009) Friendship ties and geographical mobility: evidence from Great Britain. J R Stat Soc Ser A 172(2):427–442

Bönisch P, Schneider L (2010) Why Are East Germans Not More Mobile?: Analyzing the Impact of Local Networks on Migration Intentions, SOEPpapers on Multidisciplinary Panel Data Research 334, DIW Berlin

Bönisch P, Schneider L (2013) The social capital legacy of communism-results from the Berlin Wall experiment. Eur J Polit Econ 32:391–411

Broulíková HM, Huber P, Montag J, Sunega P (2018) Homeownership, Mobility, and Unemployment: Evidence from Housing Privatization WIFO Working Papers 548, WIFO

Cattaneo C (2016) Opting into opt out? Emigration and group participation in Albania. Int Migr Rev 50(4):1046–1075

Cojocaru A (2014) Fairness and inequality tolerance: evidence from the Life in Transition survey. J Comp Econ 42(3):590–608

Dahl MS, Sorenson O (2010) The social attachment to place. Soc Forces 89(2):633–658

David Q, Janiak A, Wasmer E (2010) Local social capital and geographical mobility. J Urban Econ 68(2):191–204

Durlauf SN, Fafchamps M (2005) Social capital. In: Aghion P, Durlauf S (eds) Handbook of Economic Growth, Vol. 1, Elsevier, pp 1639–1699

Fidrmuc J (2004) Migration and regional adjustment to asymmetric shocks in transition economies. J Comp Econ 32(2):230–247

Fidrmuc J, Gërxhani K (2008) Mind the gap! Social capital, East and West. J Comp Econ 36(2):264–286

Fouarge D, Ester P (2008) How willing are Europeans to migrate? A comparison of migration intentions in Western and Eastern Europe. In: Ester P, Muffels R, Schippers J, Wilthagen T (eds) Innovating European labour markets dynamics and perspectives. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, pp 49–72

Huber P (2005) Inter—regional mobility in the accession countries: a comparison to EU15-member states. Zeitschrifft für ArbeitsmarktForschung J Labour Mark Res 37(4):393–408

Huber P, Nowotny K (2016) The impact of relative deprivation on return intentions among potential migrants and commuters. J Reg Sci 56(3):471–493

Kan K (2007) Residential mobility and social capital. J Urban Econ 61(3):436–457

Mihaylova D (2004) Social Capital in Central and Eastern Europe. Central European University, Budapest, Center for Policy Studies, Budapest

Nikolova E, Sanfey P (2016) How much should we trust life satisfaction data? Evidence from the life in transition survey. J Comp Econ 44(3):720–731

Paci P, Tiongson ER, Walewski M, Liwiński J (2010) Internal labour mobility in Central Europe and the Baltic Region: Evidence from labour force surveys. In: Caroleo FE, Pastore F (eds) The labour market impact of the EU enlargement: a new regional geography of Europe? Springer, pp 197–225

Paldam M, Svendsen GT (2001) Missing social capital and the transition in Eastern Europe. J Inst Innov Dev Trans 5:21–34

Pop-Eleches G, Tucker JA (2013) Associated with the past? Communist legacies and civic participation in post-communist countries. East Eur Polit Soc 27(1):45–68

Portes A (1998) Social capital: its origins and applications in modern sociology. Ann Rev Sociol 24(1):1–24

Rainer H, Siedler T (2009) The role of social networks in determining migration and labour market outcomes. Econ Transit 17(4):739–767

Raiser M, Haerpfer C, Nowotny T, Wallace C (2002) Social capital in transition: a first look at the evidence. Sociologický časopis/Czech Sociol Rev 38:693–720

Tabellini G (2010) Culture and institutions: economic development in the regions of Europe. J Eur Econ Assoc 8(4):677–716

Van Dalen HP, Henkens K (2008) Emigration Intentions: Mere Words or True Plans? Explaining International Migration Intentions and Behavior, Discussion Paper 2008-60, Tilburg University, Center for Economic Research

Weiss HE (2012) The intergenerational transmission of social capital: a developmental approach to adolescent social capital formation. Sociol Inq 82(2):212–235

World Bank (2009) World Development Report 2009: Reshaping the Economic Geography. The World Bank, Washington DC

Zhao L, Yao X (2017) Does local social capital deter labour migration? Evidence from rural China. Appl Econ 43:4363–4377

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Annex 1: Coding of dependent and key independent variable

Annex 1: Coding of dependent and key independent variable

This annex describes the coding of the main dependent and independent variables.

-

Willingness to migrate—the dependent variables are constructed from two questions that read: “Would you be willing to move elsewhere in our country for employment reasons?” and “Would you be willing to move abroad for employment reasons?” Respondents could reply “yes” or “no”. Respondents answering at least one question affirmatively are willing to migrate. Those that answered the first question positively are willing to migrate within the country and those that responded positively to the second question are encoded as being willing to migrate abroad.

-

Meet friends and meet family—these measures are based on two questions asking, “How often do you meet up with family members not living in your household?” and “How often do you meet up with friends?” with responses being 1 = On most days, 2 = Once or twice a week, 3 = Once or twice a month, 4 = Less than once or twice a month, 5 = Never.

-

Memberships in clubs and civil society organizations—is based on a question that reads as “Here is a list of clubs and civil society organizations. For each one, please indicate, whether you are an active member, an inactive member, or not a member of that type of organization”. The list of organizations was (a) churches and religious organizations, (b) sport and recreational organizations and associations, (c) art, music and educational organizations, (d) labour unions, (e) environmental organizations, (f) professional associations, (g) humanitarian and charitable organizations, (h) youth organization and (i) parties. The variable was formed by taking the count of organizations of which the respondent was at least an inactive member.

-

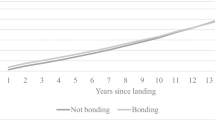

Years of residence—is based on the question “How long have you lived in this city/town/village?”. Respondents could either provide the number of years or state that they had lived in the city/town/village for their whole life. For persons, who responded that they had lived in the city/town/village for their whole, life their age was entered as the years of residence.

Table 6 Instrumental Variable Regression results

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Huber, P., Mikula, S. Social capital and willingness to migrate in post-communist countries. Empirica 46, 31–59 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10663-018-9417-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10663-018-9417-7