Abstract

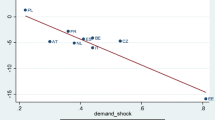

Profits that persist above or below the norm for prolonged periods of time reveal a lack of competition and imply a systematic misallocation of resources. Competition, if unimpeded, should restore profits to normal levels within a relatively short time frame. The dynamics of profits can thus reveal a great deal about the competitiveness of an economy. This paper estimates the persistence of profits across the European Union (EU), which adds to our understanding of the competitiveness of 18 EU member states. By using a sample of approximately 4700 firms with 51,000 observations across the time period of 1995–2013, we find differences in the persistence of short-run profits, implying that there are differences in competitiveness across the EU. The Czech Republic and Greece are among the countries with the highest profit persistence, whereas the United Kingdom is among those with the lowest persistence of profits. Furthermore, we provide evidence that there are significant permanent rents present in the EU across countries as well as in the different broad sectors across the EU.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Competition is a dynamic process driven by the entry and exit of firms, innovation and adaptation. This competitive process produces outcomes in which the prices and the variety of products are set in numerous complex ways over time by a dynamic composition of firms. The most common way to measure the strength of market competition has been by making a cross sectional analysis of profitability, as profits provide a measurement of the deviation of prices from marginal cost, which, in turn, provides information on the performance of the market and the firms. A market is perceived as more competitive if profits above the norm do not persist for any extended period of time.

In the literature, there are two distinctly different views of profits: a static view and a dynamic view. Under the static view, profits above the norm reflect some monopoly power, which is upheld by entry barriers. Under the dynamic view, entrepreneurs, driven by the profit motive, introduce innovations and thereby create temporal monopolies. The latter is sometimes referred to as the Schumpeterian view of profits. However, we do not expect the profits of these temporal monopolies to persist (see Mueller 1976, 1986, 2015 for a discussion). Thus, there are two ways profits can behave in the long run. Either profit rates will converge to a zero-profit (competitive return) where all monopoly rents have been eliminated, or profits will persist.

The so-called persistence of profits literature, which examines the dynamics of profits, has increased steadily since the seminal contributions of Mueller (1976, 1977, 1986). Empirically, there is strong support for the persistence of profit hypothesis, and the notion of fully competitive markets has been rejected. Today, there is a significant body of persistence of profit studies. Studies have been conducted at the industry level, e.g., Mueller (1990), Yurtoglu (2004), and Schumacher and Boland (2005) and at the country level, e.g., Kambhampati (1995), India; Cubbin and Geroski (1987), the United Kingdom; and Jenny and Weber (1990), France. Cross-country comparison studies have also been conducted, e.g., Geroski and Jacquemin (1988), Glen et al. (2001) and Goddard et al. (2005). We add to the literature by providing profit persistence estimates for 18 EU countries, and to our knowledge, the inclusion of such a large number of countries, which enables direct comparisons, has not previously been performed. In addition, we compare the profit dynamics across 10 different sectors across the EU.

The questions as to what extent firms have persistent profits and how the persistence differs between the various EU states not only represent an important research theme but also have important policy implications. Through the European integration, firms have gained access to markets that were previously unattainable to them in recent decades, which suggests that firms have an opportunity to operate in new, more extensive markets and that the opening of markets may additionally produce increased competition and competitive pressure for the domestic incumbents. Nevertheless, the performance of a firm is still influenced by factors specific to the firm’s country of origin, and arguably, convergence to a single market in the EU has not been fully achieved. If this was the case, we would expect the same persistence of profit pattern across the single market. According to Geroski and Jacquemin (1988), the variations among the speeds of profit convergence may be due to differences in the strength of anti-trust policies and country specific regulatory systems.

High levels of profits that are either above or below normal profits are a concern for policy makers, since this implies a systematic misallocation of resources. Markets that are less competitive will exhibit such abnormal profits for a longer time, creating welfare losses. If innovations enable firms to withstand the erosion of profits from competition, the welfare effects of the innovations are likely to outweigh the welfare losses caused by the temporal monopolies. However, as Gschwandtner and Lambson (2002) discuss, profit persistence may not only be a sign of misallocation of resources but also stems from sunk costs.

The focus of this paper is on the differences in the persistence of profits for a sample of 18 EU countries between 1995 and 2013. We look at cross-country differences in the persistence of profits but also across broadly defined sectoral differences in the EU. The study includes 4665 listed firms and a total of 50,611 observations. We use the simple first-order autoregressive model, which maintains comparability to previous studies. First, we run the estimates for firms individually, we then aggregate and report country and sector averages. We run firm-level estimations, since profit persistence is strongly related to a time series dimension instead of a cross-section, and restrictions are imposed by a low number of observations for some of the sample countries.Footnote 1 In addition, we also control for the impact of the 2008 subprime crisis.

A study that incorporates this many countries, to our knowledge, has not been conducted previously, and thus this is one of the main contributions of this paper, as it enables direct comparisons regarding the competitiveness of different EU member states. Additionally, we include more than one sector in the analysis, i.e., we impose no restrictions on the industry in which the firm is operating in. We do this to capture a full representation of the economy for a given country, and we also examine the profit persistence across 10 broad sectors for the whole EU. Our findings suggest that the competitive forces are relatively weak in, for example, Greece, whereas they are stronger in the UK and Sweden.

2 Competition and the persistence of profits

As mentioned, there are two alternative ways to view competition. According to the first perspective, competition is viewed as a process for determining prices and quantities, and the monopoly problem consists of too few sellers who produce insufficient output at excessive prices. Following this perspective, competition policies are built on the inference that the divergence between price and cost is greater in concentrated industries, and thus welfare losses must be greater in such industries, since an insufficient amount of goods is traded. A problem with empirical studies following this tradition is that they may be capturing transitory disequilibrium phenomena (Mueller 1977). According to the second alternative, which is a more dynamic view of competition, products can be heterogeneous, and non-price modes of competition prevail. Such markets are better characterized by a competition process, where the entry and exit of firms are central components. This view of competition is associated with the Schumpeterian-like model of dynamic competition.

In Schumpeter’s 1934 description of “creative destruction”, firms and entrepreneurs compete with one another by introducing innovations and copying the innovations of others. In an extreme case, a firm’s innovation creates an entirely new industry, as the innovator starts as a monopoly earning monopoly profits. This, however, attracts imitators who erode the innovator’s excessive profits until all firms in that market earn profits equal to the competitive norm. Thus, under this dynamic view of competition, the entry and exit of firms drive excess profits to zero in the long run. Since this dynamic view allows for the possibility of differences in profits across firms at any given point in time, studies testing it have concentrated on determining whether or not profits persist.

A firm’s profit can be decomposed into three components (Mueller, 1976): (1) a competitive return common to all firms (c), (2) a permanent rent specific to firm i (ri), and (3) a firm’s specific short-run rent or quasi rent, (sit), expressed as:

In fully competitive markets, firms would, in the long run, earn profits that are equal to the competitive return (c) after a sufficient amount of time, but as the short-run rents are correlated over time, it may take some time for them to return to the competitive norm. Previous studies have estimated whether short-run rents (sit) erode and whether there are significant permanent rents (ri). Following Mueller (1977, 1986), the empirical model to estimate the persistence of profits can be formulated using the following simple first-order autoregressive modelFootnote 2:

where πit is measured as the deviation from the mean,Footnote 3πit−1 is the profit of the previous period and uit is the conventional error term. The coefficient λi is the short-run profit persistence parameter. The profits are therefore typically dependent on their past values, with a mean reverting process.Footnote 4

Equation 2 yields two measures of the persistence of profits in which the short-run estimate is of our main interest. First, the coefficient λi indicates the speed of convergence to the normal level of profits in the short run, i.e., short-run profit persistence. A value close to zero implies that the competitive process erodes the excess profits within this period. A value close to one indicates that the profits do not erode within the period and that competition has failed to affect the persistence of profits. Second, the firm-specific permanent rent is estimated as \(\hat{p}_{i} = \hat{\alpha }_{i} /( {1 - \hat{\lambda }_{i} })\). It indicates the steady-state equilibrium value towards which the profits converge. If \(\hat{p}_{i} = 0\), the permanent rent equals the competitive norm and there are no long-run excess profits. Since we have a relatively short period of data availability, we focus on the short-run estimates. However, we indicate the share of firms with \(\hat{\alpha }_{i}\), and therefore \(\hat{p}\) is significantly different from zero in a given country, as it measures the degree of permanent firm-specific rents.

2.1 Previous literature

The dynamic view of industry competition proposes that in a competitive market, normal profits will emerge in the long run as the result of the entry and exit of firms. Many studies conducted during recent decades have tested this. In Table 1, the previous empirical literature conducted for countries outside of Europe is summarized, and Table 2 summarizes the studies of European economies. The last column, mean \(\hat{\lambda }_{i} ,\) presents the short-run estimates reported in each study or if not readily available, those calculated by the authors based on the study. The estimations reported in Tables 1 and 2 are based both on individual firm estimations as well as panel estimations.

The majority of the studies both outside and in Europe are based on the analysis of a single industry, with a particular focus on the manufacturing industry. Some exceptions to this are, for example, Schumacher and Boland (2005) and Hirsch and Gschwandtner (2013), who focus on the food or dairy industry, and Cable and Jackson (2008), who include both manufacturing and service sector firms. When comparing the number of firms included in the samples to previous research, the sample sizes for a given country range from a minimum of 4 in Cable and Mueller (2008) to a maximum of 4620 in Goddard et al. (2005). On the other hand, the minimum time period found in previous studies is 9 years in Goddard et al. (2005) and the maximum of 50 is found in a handful of studies, e.g., Gschwandtner (2005). Long time periods are preferred when studying profit persistence, since it might take a considerable amount of time to capture the actual long-run profits. We have firms with up to 19 years of observations in our sample, which in comparison to previous studies, seems to be sufficiently long.Footnote 5 Our sample size for each country varies from 17 firms in Estonia to 1444 in the United Kingdom, and we include the entire economy with all of the industries present.

There exists a relatively large volume of literature regarding the United States, whereas the majority of the European studies have focused on specific large countries, such as Belgium, France, Germany, Italy and the United Kingdom. Glen et al. (2001) and Yurtoglu (2004) study profit persistence in selected emerging countries, whereas e.g., Odagiri and Yamawaki (1986) focus on Japan. However, there is a lack of evidence regarding the persistence of profits in the smaller European economies. Additionally, while objectives exist for creating a single European market, it is important to examine the differences in competitiveness across the European Union member states. Accordingly, we add to the literature by providing evidence for a large sample of 18 EU countries.

Most previous studies use ordinary least squares (OLS) and measure profit convergence by using between one and four lags. A few more recent studies used dynamic panel model estimations, mainly because their data covered a long period of time. Furthermore, as seen in Tables 1 and 2, a handful have investigated the properties of profit persistence using structural time series analysis, which does not yield comparable mean convergence values (\(\hat{\lambda }_{i}\)) per se. There have been other improvements in the method, such as Crespo Cuaresma and Gschwandtner (2006), who utilize non-linear profit persistence; Crespo Cuaresma and Gschwandtner (2008), who use time-varying persistence; and Gschwandtner and Hauser (2008), who measure the persistence with a fractional integration method. Although these improvements have been made and are desirable in many ways, we estimate OLS by firm, with one lagged dependent variable. We do this mainly to maintain comparability with most the previous studies and also because some of the improvements imply restrictions to the data, which are not ideal or suitable in our case.

3 Data and empirical estimations

We use firm-level data from the Compustat Global Database for 18 EU countries for the time period 1995–2013, all of which report annual data. We use return on assets (RoA) as a measure of profits. Our sample consists of 4665 firms and includes a total of 50,611 observations. Because we allow firms to enter and exit, the number of observations among firms differs, as summarized in Table 3. Previous studies have largely focused on samples of firms that survive the entire sample period, but this arguably ignores valuable information. Gschwandtner (2005) argues that by analyzing only surviving firms, one might build an artificial stability into the sample, and thus the exit and entry of firms are an important part of the dynamic adjustment process of the market.Footnote 6

We have not accounted for the possibility of mergers in our sample, as data on merger activities are not available. The included firms in our analysis are publicly listed firms in their respective countries. Furthermore, the number of listed firms within a country differs among the sample countries, as stated in the previous section and exemplified in Table 3. The sample countries are selected to provide a good representation of both large and small economies in the EU as well as countries for which data are sufficiently available.Footnote 7

We provide an extensive representation of the entire economy and include all sectors rather than focusing exclusively on a single sector or industry. However, the manufacturing sector comprises 44% of the total observations in our sample. We define sectors at the one-digit levelFootnote 8 to estimate the profit persistence across these industries: agriculture, construction, finance, manufacturing, mining, public administration, retail, services, transport, and wholesale. The usual data caveats apply.

Table 3 summarizes the data with respect to the distribution and coverage among the sample countries.

Following the literature, our dependent variable, profit, is calculated as the return on assets’ deviation from the sample mean, as described before. We trim return on assets by the 1 and 99% percentiles and exclude values that are less than − 25. Return on assets is defined as net income over total assets, and it is a common measure of profits used in the literature. Accounting profits are arguably suitable to reflect real economic profits, which is discussed in greater depth by, among others, Fisher and McGowan (1983) and Long and Ravenscraft (1984). In addition, accounting profits are easily available and comparable across firms.

To measure the convergence process, we add one lagged value of our dependent variable as an explanatory variable. The autoregressive process is of interest and the coefficient of the lagged value provides insight into the competitiveness of the economies in the short term.

We exclude firms with explosive behavior, i.e., \(|\hat{\lambda }_{i} | > 1\), which comprise 7.4% of all the data.Footnote 9 Additionally, because we have a relatively short time period in our sample, we focus on the short-run estimates of the convergence process. The minimum number of observations for a given firm used in the paper is five, as seen from Table 3, i.e., a firm had to survive for at least five years to be represented in our sample.

We estimate Eq. 2 individually by firm using ordinary least squares and report the averages of the estimates first, by country and second, by sector across the EU. The firm-level estimations are preferred to panel data estimations, since we have a relatively short time period, profit persistence is strongly related to a time series dimension instead of a cross-section, and we have some countries with a low number of firms and observations. We also, mutatis mutandis, estimate the panel version of Eq. 2 as a robustness check, which is reported in Appendix Table 10.

4 Results

We control for firm heterogeneity by performing an OLS on individual firms, as shown in Table 4. The four first columns after the column with the name of the country in Table 4 are the share of firms in the sample whose profit persistence parameters fall within a given interval for that country. The higher the share of firms that fall in the lower range values of \(\hat{\lambda }_{i}\), i.e., either − 0.5 to 0 or 0 to 0.5, the more competitive the economy is in the short run. The mean convergence parameter \(\hat{\lambda }_{i}\) is calculated as the mean of all the firm’s parameters. We report both the absolute and unadjusted values of \(\hat{\lambda }_{i}\). To compare the mean values of the short-run parameter is problematic when there are both negative and positive values, since the lowest values of the parameter will drive down the mean value while being a sign of low competition, and therefore the absolute values of \(\hat{\lambda }_{i}\) are preferred. The table is ordered from the lowest to highest short-run estimates \(( {|\hat{\lambda }_{i} |})\). The last two columns indicate the percentage of firms for which the short-run convergence parameter \(\hat{\lambda }_{i}\) and the intercept term \(\hat{\alpha }_{i}\) are significantly different from zero at the 5% level within each country.

Table 4 presents the results for short-run persistence; it is evident that there are significant short-run profits across the countries in the EU, as, on average, 26% of firms have coefficients significantly different from zero at the 5% confidence level. The average short-run profit persistence parameter for the entire dataset is 0.421. Therefore, the markets are not fully competitive in the short run, since the very existence of the significant coefficients provide evidence that the markets are not fully competitive in any of the countries in our sample. The countries in the middle of the list exhibit relatively small variations in the convergence parameters, whereas differences arise at the lower and higher ends of the distribution. It is evident that most economies, excluding the bottom three, have more than half of the firm’s parameter values between 0 and 0.5 in absolute terms, i.e., at the lower end of the parameter distribution.

The United Kingdom, Portugal, Sweden and Germany emerge as the most competitive economies in the short term among the sample of European economies with the lowest short-run persistence parameters. The United Kingdom, Portugal and Sweden are the only economies with less than 20% of the short-run profit persistence parameters being significant. These countries also have above 70% of all of their firms’ parameters in the lower range of the parameter distribution, between 0 and 0.5, in absolute terms. Firms in these relatively competitive economies are not able to maintain profits above normal, as it takes less than a year for the value to reach half of its initial value.

The Czech Republic, followed by Greece, Spain and Estonia have the highest short-run profit persistence among our sample. In the Czech Republic, it takes more than a year for the profits to be half of their initial value, as shown by the average short-run persistence coefficient of 0.539. Greece, Spain and Estonia have average coefficients of just below 0.5, indicating that it takes close to a year for firms in these economies. We can additionally see that the Czech Republic, Greece and Spain have 50% of their firms’ coefficients on the upper scale of the distribution, between 0.5 and 1, implying less competition, as they have high persistence in these economies. These economies also, in general, have the higher share of parameters that are significantly different from zero based on a significance level of 5%.

Regarding robustness, we add in the appendix Table 8 an estimation where we exclude firms with less than 10 observations. The excluded firms are mainly located in the negative, more volatile, side of the parameter distribution; therefore, the estimates are systematically higher. As noted in the literature and in the previous section, analyzing only (or longer) surviving firms creates artificial instability in the data. The firms with low short-run parameter values, i.e., \(- 1 < \hat{\lambda }_{i} < 0\), have a higher probability to exit the market, and keeping them adds valuable information regarding the economies. We also add Table 9 in which we evaluate the firms with only positive convergence. The rank of the countries in both 8 and 9 are relatively robust, with expected systematically higher mean short-run parameter values. We also run panel estimations for each country, and the results from a fixed effects estimator is provided in appendix Table 10. The estimated parameter values for the fixed effects regression are lower than those of our results in Table 4. However, the correlation of the ranks of the countries between Table 4 and the fixed effects estimation is approximately 0.66. One advantage of the fixed effects estimator is that one can control for time-invariant firm-specific effects. However, this does not affect the firm-level OLS estimations, as we do not pool the firms. The individual OLS estimators are preferred, as they allow us to estimate firm-specific intercepts and slope coefficients for which a fixed effects estimator would not allow.

However, we are not able to distinguish whether our persistence parameter values are driven by (1) vigorous innovating activities or (2) a lack of competition; therefore, we cannot conclude much regarding the middle-range countries’ parameter values other than that they are close to each other. Since we do not study the factors that cause the persistence of these profits, we cannot definitely state what specifically these countries act upon. However, we demonstrate that (1) profit persistence differs among the sample countries, (2) which sample countries perform the worst or best in the short run, with respect to profit convergence given the time period, and (3) there exists significant long-run permanent rents. More should be done with respect to the underlying reasons why this is so in future work.

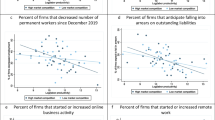

Since the 2008 subprime crisis occurred during the time period of our sample, we also investigate the impact it had on the persistence of profits across the countries. We add a post 2007 dummy as well as an interaction between the lagged profit variable and the post 2007 dummy to account for what impact the crisis might have had on both the short-run and the permanent rents of firms, which is described as:

The crisis dummy captures the effect the crisis had on the long-run persistence, whereas the interaction of the dummy and the lag of the dependent variable captures the effect on the short-run profit persistence. This is preferable to dividing the sample in post- and pre-crisis samples, since we lose degrees of freedom and the post-crisis time period is much shorter. We, however, include the estimations of dividing the sample to pre- and post-crisis periods in appendix Table 11. Regarding the robustness of our main results, the correlation of the pre-crisis rank and the rank of countries in Table 4 is 0.72 and shows that our results are not driven by the crisis.

The results in Table 5 show that relatively few firms’ profit persistence parameters were affected by the 2008 crisis across our sample countries, 3% of the firms, on average, in the short run. However, in this small group of firms, the economic effect was strong, i.e., mainly implying non-convergence after the crisis.Footnote 10 The average value of the short-run persistence measure for those firms with significant effects after the crises is either a very low or high value, for example, France with − 7.87. Slovenia has the highest share of firms affected by the crisis, with 10% of the firms having a significant coefficient of the short-run profit persistence post 2007 and of those, 10% of the firms had an average of − 0.821 lower short-run persistence after the crisis. The drop in output was one of the largest in Slovenia across the OECD after the crisis, and the Slovenian central government has been slow in reacting to the crisis in general (OECD 2015). Three countries that seem not to be affected in their short-run persistence are Estonia, Hungary and the Czech Republic.Footnote 11 These countries also have high values for short-run profit persistence in Table 4. It can be the case that the crisis manifested itself in these countries through firms exiting the market or the governments subsidizing firms after the crisis, which resulted in no impact on the short-run profit persistence.

As a further robustness test, we split the sample to pre- and post-crisis periods and run estimations separately for the two time periods to look at how the persistence parameters were affected by the 2008 crisis (see appendix Table 11). The results show that the persistence parameters are lower for each country, on average, after the crisis,Footnote 12 whereas the pre-crisis rank of countries is nearly identical. The results should be interpreted with caution, as splitting the sample results in lost degrees of freedom. In particular, the post-crisis time period comprises only 5 years of data, whereas the pre-crisis period includes thirteen years of data. Additionally, the number of firms included in the two time periods differs, as firms are allowed to exit and enter the time period.Footnote 13 Therefore, the results in Table 5 above are more reliable.

Our results, in general, indicate, in alignment with previous research, that profits persist in the long run, as shown in both Tables 4 and 5. On average, as shown in Table 4, 13% of firms experience either below or above normal long-run profits. As for the long-run persistence results in Table 5, an average of 7% of firms across the EU have a significant post 2007 crisis dummy. Estonia and the Czech Republic did not seem have any firms that had a significant effect from the crisis. Conversely, 19% of Slovenia’s firms did endure a significant change on their long-run profit persistence parameters.

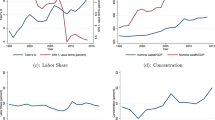

4.1 Sectoral evidence

The cross-country variation that we observe can be caused by differences in industry composition, and this leads us to also examine the dynamics of profit across sectors. We look at profit persistence across sectors for the entire EU and investigate the differences in their short-run and long-run profit persistence. Equation 2 is, therefore, run for individual firms, as shown in the previous section, but now the information is aggregated across ten broad sectors: agriculture, construction, finance, manufacturing, mining, public administration, retail, services, transport, and wholesale.

The results from Table 6 show that there are disparities across the sectors in the EU, ranging from 11% of firms in public administration having significant short-run profit persistence to 35% in the construction sector. The public administration and agriculture sectors have the lowest short-run persistence parameters. The public administration sector includes mainly firms that are publicly owned, such as firms working with national security and international affairs or legislative bodies. These types of firms do not follow a regular profit motive; therefore, the low short-run profit persistence is not necessarily a sign of high competition but instead manifests public pressure not to show high short-run profits but still having permanent rents due to the lack of competition in the long run. The agricultural sector, on the other hand, especially in the EU, is heavily subsidized and is also subject to obey EU regulations. In the short run, the firms seem to have a rapid convergence of profits to the industry norm, but there are many firms with significant permanent rents. It can be the case that the low short-run profits are a sign for the governmental bodies that the subsidies the firms receive are not used for high profits but rather are invested in machinery, R&D or similar activities.

The construction, retail and wholesale sectors emerge as having the highest short-run profit persistence; there are above 25% of firms with significant short-run profit persistence parameters with the highest share of the parameters in the high end of the parameter distribution. These industries, especially construction, are characterized by having scale economies; therefore, natural monopolies are common. In certain economies, some construction firms have even been prosecuted for colluding and forming cartels. Therefore, the short-run profit persistence in these sectors imply the anti-competitive behavior of the sectors as a whole.

The results also would indicate that the differences among the EU countries can be at least partially explained by the industry composition for a given economy. We execute the same procedure as in the previous section and estimate the impact of the 2008 crisis on the persistence parameters for the broad sectors by adding a post-2007 dummy and the interaction term of the crisis dummy with the lag of the profits, as illustrated in Eq. 3. As stated previously, the dummy for the crisis captures the impact the crisis had on long-run persistence, whereas the interaction of the post-crisis dummy and the lag of profit (\(\hat{\lambda }_{2i}\)) captures the effect on short-run profit persistence.

The same pattern arises in Table 7 as when we aggregate the information to the country level, nearly all firms significantly affected by the crisis have exploding (non-converging) profit persistence post-2007. The agricultural sector incurred the largest impact of the crisis in profit persistence, as shown by 8% of the firms having a significant effect of their short-run estimator, with an average value of − 1.27. On the other hand, 4% of the firms within the manufacturing sector have a significant post-crisis short-run parameter, with a high absolute number of firms, almost 2000 firms are in the agriculture sector. The firms that had a significant impact from the crisis in the manufacturing sector have an explosive oscillating convergence after the crises, with an average value of − 3.95. Production, in general, during the crisis, fell dramatically across the globe and therefore, also in the EU. Four percent of all firms in the manufacturing, mining, construction and retail sectors were affected by the crisis in the short term.

The public administration and financial sector firms’ short-run profit persistence parameters were not impacted by the crisis. During and after the crisis, national governments were bailing out banks; eventually, even the European Central Bank intervened in the financial sector. According to a European Commission (2009) report, central banks in the member countries cut interest rates to ensure they were low, gave financial institutions access to lender-of-last-resort facilities, gave guarantees on financial institutions liabilities, and provided capital injections and impaired asset relief. In addition, it is possible that we may not see any impact on the finance sector because the firms who survived gained large public financial support for their operations, whereas some portion simply exited (went bankrupt), leaving the persistence parameter unchanged. Therefore, one could argue that the heavy involvement of both domestic governments and the EU body might be contributing factors of why the financial crisis did not impact the financial sector’s profit persistence. The firms in the public administration sector were also unaffected by the crisis in the short run, but as public defense and legal issues are somewhat independent of certain macroeconomic shocks, at least in the short run, there is no impact in the short-run persistence parameters. However, 3% of the firms in public administration did incur changes in their long-run persistence parameters after the crisis.

5 Conclusion

The more competitive a market economy is, the faster profits above or below the norm should be restored to competitive levels. To put it differently, in a competitive milieu, we would expect a low level of profit persistence. Our results indicate that there are economically significant differences in the competitiveness among the EU states in the short run. In general, the United Kingdom, Sweden and Germany are the countries with the lowest profit persistence, whereas the Czech Republic, Greece, and Spain are the least competitive economies with the highest persistence of profits.

Studying a large sample of firms across EU, we show that there are disparities across different sectors. The public administration and agricultural sectors have the lowest short-run profit persistence, whereas construction, wholesale and retail are the ones with the highest. We also show the impact that the 2008 subprime crisis had on the profit dynamics across the EU member states and across the different sectors in the EU.

Notes

This approach also enables us to avoid including restrictions about common intercepts or parameters among firms, as well as identifying and excluding firms with explosive short-run profit persistence behavior. The differences in the ranking of countries between our main results in Table 4 and the fixed effects estimations in the appendix (Table 10) have a correlation of 0.66.

\(\pi_{it} = return\,on\,assets_{i,t} - \sum\nolimits_{i}^{N} {return\, on\, assets_{i,t} /Number\, of\, firms_{t} }\). By subtracting the mean, the cyclical component of profits common to all firms and countries are removed.

The time period does vary among firms within a country, but on average, we have 19 year observations and use 18 years for the estimations, since we lose the first year due to adding a lag. As can be seen in Table 3, some countries do not have any firms who survive the entire period.

This is verified in Table 8, where we exclude firms that have less than 10 years of data.

However, results for the countries with a low number of firms should be interpreted with caution, especially the panel estimations.

Information about the industry of a firm is given as the Standard Industrial Classification (SIC) code.

As we run estimations of firms individually instead of pooling then in a panel, we can distinguish and exclude these firms. This is common practice in the literature.

Both positive and negative explosive behavior of the short-run persistence parameter.

As to answering precisely and deterministically why these three countries were not affected, while firms in other economies were, is beyond the scope of this paper. Some plausible explanations might be that some countries had better policy responses to the crisis than other economies, firms in some of the countries were more flexible in responding to the macro shock because of firm-specific resources such as managerial abilities, or some countries had more favorable institutions at the time of the crisis. An alternative explanation might be in the industry composition of the country, where some industries might have been more impacted by the crisis than others, which is analyzed in depth in the next section; therefore, the overall industry composition of a country might be one explanation for differences in the impact of the crisis.

However, we have not tested for the difference statistically.

References

Cable JR, Gschwandtner A (2008) On modelling the persistence of profits in the long run: a test of the standard model for 156 US companies, 1950–99. Int J Econ Bus 15(2):245–263

Cable JR, Jackson RH (2008) The persistence of profits in the long run: a new approach. Int J Econ Bus 15(2):229–244

Cable JR, Mueller DC (2008) Testing for persistence of profits’ differences across firms. Int J Econ Bus 15(2):201–228

Crespo Cuaresma J, Gschwandtner A (2006) The competitive environment hypothesis revisited: non-linearity, nonstationarity and profit persistence. Appl Econ 38(4):465–472

Crespo Cuaresma J, Gschwandtner A (2008) Tracing the dynamics of competition: evidence from company profits. Econ Inq 46(2):208–213

Cubbin J, Geroski P (1987) The convergence of profits in the long run: inter-firm and inter-industry comparisons. J Ind Econ 35:427–442

Cubbin J, Geroski P (1990) The persistence of profits in the United Kingdom. In: Mueller DC (ed) The dynamics of company profits. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Fisher FM, McGowan JJ (1983) On the misuse of accounting rates of return to infer monopoly profits. Am Econ Rev 73(1):82–97

Geroski PA, Jacquemin A (1988) The persistence of profits: a European comparison. Econ J 98(391):375–389

Glen J, Lee K, Singh A (2001) Persistence of profitability and competition in emerging markets. Econ Lett 72(2):247–253

Goddard JA, Wilson JO (1999) The persistence of profit: a new empirical interpretation. Int J Ind Organ 17(5):663–687

Goddard J, Tavakoli M, Wilson JO (2005) Determinants of profitability in European manufacturing and services: evidence from a dynamic panel model. Appl Financ Econ 15(18):1269–1282

Gschwandtner A (2005) Profit persistence in the ‘very’long run: evidence from survivors and exiters. Appl Econ 37(7):793–806

Gschwandtner A (2012) Evolution of profit persistence in the USA: evidence from three periods. Manch School 80(2):172–209

Gschwandtner A, Cuaresma JC (2013) Explaining the persistence of profits: a time-varying approach. Int J Econ Bus 20(1):39–55

Gschwandtner A, Hauser M (2008) Modelling Profit Series: Nonstationarity and long Memory. Appl Econ 40(11):1475–1482

Gschwandtner A, Lambson VE (2002) The effects of sunk costs on entry and exit: evidence from 36 countries. Econ Lett 77(1):109–115

Hirsch S, Gschwandtner A (2013) Profit persistence in the food industry: evidence from five European countries. Eur Rev Agric Econ 40:741–759

Hirsch S, Hartmann M (2014) Persistence of firm-level profitability in the European dairy processing industry. Agric Econ 45(S1):53–63

Jenny F, Weber AP (1990) The persistence of profits in France. In: Mueller DC (ed) The dynamics of company profits. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Kambhampati US (1995) The persistence of profit differentials in Indian industry. Appl Econ 27(4):353–361

Kessides IN (1990) The persistence of profits in US manufacturing industries. In: Mueller DC (ed) The dynamics of company profits. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Khemani RS, Shapiro D (1990) The persistence of profitability in Canada. In: Mueller DC (ed) The dynamics of company profits. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Long WF, Ravenscraft DJ (1984) The misuse of accounting rates of return: comment. Am Econ Rev 74(3):494–500

Maruyama N, Odagiri H (2002) Does the ‘persistence of profits’ persist?: a study of company profits in Japan, 1964–1997. Int J Ind Organ 20(10):1513–1533

McGahan AM, Porter ME (1999) The persistence of shocks to profitability. Rev Econ Stat 81(1):143–153

McMillan DG, Wohar ME (2011) Profit persistence revisited: the case of the UK*. Manch School 79(3):510–527

Mueller DC (1976) Information. Mobility and Profit, Kyklos 29(3):419–448

Mueller DC (1977) The persistence of profits above the norm. Economica 44(176):369–380

Mueller DC (1986) Profits in the long run. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Mueller DC (1990) Profits and the process of competition. In: Mueller DC (ed) The dynamics of company profits. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Mueller DC (2015) Profits, entrepreneurship and public services. In: Eklund J (ed) Vinser, Välfärd och Entreprenörskap. Swedish Entrepreneurship Forum, Stockholm

Odagiri H, Yamawaki H (1986) A study of company profit-rate time series: Japan and the United States. Int J Ind Organ 4(1):1–23

Odagiri H, Yamawaki H (1990) The persistence of profits in Japan and The persistence of profits: an international comparison, The dynamics of company profits: an international comparison. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

OECD (2015) OECD Economic Surveys, Slovenia May 2015, OECD Economic Surveys

Schohl F (1990) Persistence of profits in the long run: a critical extension of some recent findings. Int J Ind Organ 8(3):385–404

Schumacher SK, Boland MA (2005) The persistence of profitability among firms in the food economy. Am J Agr Econ 87(1):103–115

Schumpeter JA (1934) The theory of economic development: an inquiry into profits, capital, credit, interest, and the business cycle, vol 53. Transaction Publishers, Piscataway

Schwalbach J, Mahmood T (1990) The persistence of corporate profits in the Federal Republic of Germany. In: Mueller DC (ed) The dynamics of company profits. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Schwalbach J, Graβhoff U, Mahmood T (1989) The dynamics of corporate profits. Eur Econ Rev 33(8):1625–1639

Waring GF (1996) Industry differences in the persistence of firm-specific returns. Am Econ Rev 86(5):1253–1265

Yamawaki H (1989) A comparative analysis of intertemporal behavior of profits: Japan and the United States. The Journal of Industrial Economics 37:389–409

Yurtoglu BB (2004) Persistence of firm-level profitability in Turkey. Appl Econ 36(6):615–625

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the valuable comments from Dennis C. Mueller, Björn Falkenhall and two anonymous referees. Naturally, all remaining errors are ours. We gratefully acknowledge support from the Marianne and Marcus Wallenberg foundation and from Rune Andersson and Mellby Gård AB.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Eklund, J.E., Lappi, E. Persistence of profits in the EU: how competitive are EU member countries?. Empirica 46, 327–351 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10663-018-9399-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10663-018-9399-5