Abstract

In the Kreisky era (1970–1983), Austrian government debts increased strongly. Historically, the attitude of Kreisky and the Social Democrats towards Keynesian fiscal policy measures to fight unemployment during the oil crises has been held to be responsible for the successive budget deficits. Kreisky’s ideological debt policy has become a narrative that has strongly influenced Austrian fiscal policy until today. While this explanation for the strong increase in public debt during the Kreisky era is widely accepted, it is not necessarily true. In this paper, we assess a different explanation: the deficits might simply have resulted from forecast errors of GDP growth in those turbulent times. We find that about one-third of the increase in the debt-over-GDP ratio is directly explained by short-run forecast errors, i.e., the difference between the approved and the realized budget, and an additional one-fifth is the lower bound of forecast error regarding the long-run growth rate.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

When we look at a period almost half a century ago, the extent to which the government budget deficit and its stock counterpart the public debt level are policy variables that can be affected directly is of as much relevance today as it was 50 years ago. European policy still struggles with the economic crisis in the south of Europe, and the crises of the Euro and sovereign debt have not yet been solved. Fiscal policy has been in the center of the debate then and now. On the one hand, with the state controlling or directly affecting about 40% of GDP, the budget certainly affects GDP and its fluctuations. Moreover, fiscal policy is also likely to affect long-run growth prospects within an economy. On the other hand, the budget is heavily affected by GDP, since both sides—realized government revenues and government expenditures—depend on economic outcome, i.e., the GDP.

The Kreisky period is interesting to study in this respect, because during Kreisky’s reign strong external shocks sent the Austrian economy into its first severe crisis in 25 years. These short-run shocks were coupled with long-run structural changes, i.e., the end of the catching-up growth period after World War II and the breakdown of the Bretton Woods system. While the set of problems today is of course not identical with those in the 1970s and early 1980s, with the virtue of hindsight, there is much to learn from this period. An examination of this economic era might sharpen the view on the current challenges, especially since the current malaise has again put fiscal policy at the center of the debate.

We focus in our study on GDP forecasts and forecast errors as well as changes in GDP, something that is hard to harness for insights regarding optimal responses of fiscal policy to today’s challenges. We do this nevertheless because it is important to separate “policy failures”Footnote 1 and incomplete information about the future path of the complex economic system from each other. That is necessary in order to give justice to the policy makers at the time and to their decisions about the policy-driven part in the process that resulted in public deficits. Moreover, discussing the complex system of several macroeconomic variables even in such a reduced form as we do it here has a value in itself. With respect to the current situation in Austria and Europe, we argue that simple debt-over-GDP measures are not very helpful to judge the “success” of fiscal policy.

2 Setting the stage

2.1 “Debt Chancellor’’ Kreisky

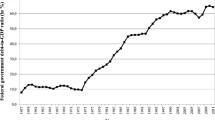

In 1970, Bruno Kreisky became Austria’s first social democratic chancellor of the second Austrian republic. A year later, the social democratic party won an absolute parliamentary majority. For the first time, the party was able to govern the country without support from other parties. Most opponents of the new government were highly unsettled about the social democratic party’s budgetary profligacy. Given the party’s clear favor for Keynesian economic policy, the fears were not that unjustified. A cursory look at the public debt data supports the view of Kreisky as “Debt Chancellor”, because Austrian government debt increased strongly within his chancellorship (1970–1983). Stating that “one billion in higher public debts” caused him “less sleepless nights than 100,000 newly unemployed” (Schellhorn 2011),Footnote 2 Kreisky himself strengthened the arguments of those who claimed that public debt had been too low on the agenda during these years. When Kreisky took office, the debt rate was not higher than 15% of GDP; when he left office, the rate was almost 40% (staatsschulden.at). During this time and in the political debate afterward, Kreisky’s chancellorship was established as the narrative for the negative consequences of deficit spending. This served to enshrine a constant or falling debt-to-GDP ratio as a policy objective in its own right. As Shiller (2017) pointed out, narratives need not be true to exert a strong political influence. They can shape or even define the political debate even without being true. The tale of “Debt Chancellor Kreisky” has certainly done this for 40 years.

The chancellorship of Bruno Kreisky took place during a time of significant changes over all of Europe. From 1960 to the first oil shock in 1973, Austria was a high-growth country with average nominal GDP growth of 10%. Like in most other countries, the oil shock decreased real growth rates sharply. Retrospectively we know that growth rates never returned to their pre-oil shock levels. By hindsight, the significantly lowered growth path would have necessitated a more restrained fiscal policy. But how could economic analysts and politicians at the time have known that the growth path had changed significantly?

2.2 Policy variables

In political debates, public discussions, and even the economic literature, the sovereign debt level is treated as a choice variable. Politicians decide about the “optimal” debt level. Depending on the perspective, various levels may be seen as optimal for the economy, society, the ruling party, or individual politicians (for economic theories of the political business cycle see Frey 1976; Bohn and Meon 2009). In this article, we want to stress that neither the debt level nor even the deficit is a choice variable. Although the political rhetoric suggests otherwise, a government decides only about a budget plan: Depending on the accuracy of forecasts of GDP growth, government expenditures, and government revenues, the approved budget may fit the realized one closely or might differ substantially.

What makes the matter even more complicated is the interdependence of the variables: GDP growth determines simultaneously the budget deficit, public spending, and tax revenues, but these variables also alter short-run and long-run growth. For example stimulus packages may stabilize the economy, in the short run, by augmenting aggregate demand, but might also foster long-run growth far beyond the time of economic distress. Thus, deciding about the “optimal” deficit level usually affects the economy and future budget and deficit in various ways.

Accurate forecasting is particularly difficult in times of great market disturbances. Forecasters lack reference periods: major market disturbances are rare, and people’s reactions in times of great uncertainty are almost unforecastable. Looking at the “short-run forecast error”, i.e., the difference between approved and realized budget deficits, government expenditures and revenues, highlights that unforeseen events determined a significant fraction of all three variables at this time. The Austrian Institute of Economic Research (Österreichisches Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung, WIFO), Austria’s main economic forecast institution, has also faced huge forecast difficulties during the time of the oil shocks.

In addition to the short-run forecast, the long-run perspective is of major political interest. At that time, economists widely agreed on the merits of anti-cyclical economic policies, however how strongly the government should lean against the negative shock, was an open question. The answer depends heavily on long run growth expectations; hence the “future normal” growth rate. A high deficit seems unproblematic if the future average nominal growth rate is 10% or more, but unsustainable if the growth rate is 2%. Wrong forecasts—the “long-run forecast error”—may cause governments to spend too much or too little. Such forecast errors have been proposed to explain the rise in unemployment in the early 1970s (see Bruno and Sachs 1985; Blanchard 2006). Bruno and Sachs argue that wage negotiations in the 1970s yielded wages that would have been warranted if productivity growth had not slowed. However the unforeseen fall in long-run productivity growth causes ‘too’ high wages and consequently unemployment. Our look at government deficits and public debts follows the same argument.Footnote 3

2.3 Related literature

The pronounced structural break in public debt in Austria around the first oil price shock has induced comprehensive research on this issue. Two research fields have been particularly intensively studied: (i) determinants for increasing and high debt levels, and (ii) the sustainability of high debt levels in Austria. While no consensus is reached so far in the first field, there is consensus in the second: the current level of governmental debt is sustainable. Neck et al. (2015), Gödl and Zwick (2018) and Bröthaler et al. (2015) apply the Bohn test to Austria and find that its level of governmental debt is sustainable. The Bohn test (Bohn 1998) assesses the long-run relationship between the predetermined debt level and the primary surplus while controlling for macroeconomic conditions. If the relationship is significantly positive, fiscal policy “reacts” to an increased stock of debt sufficiently to keep debt levels sustainable.

Neck et al. (2015) document the structural break in the time series of the debt-to-GDP ratio and suspect political economy considerations behind the strong increase of this ratio. While there are some hints for an explanation in this direction, the authors do not find reliable support for political economic effects on the debt level. The sustainability of recent debt levels, in contrast, has been confirmed. For our argument, we stress the significantly negative relationship between the unemployment rate and the primary surplus. We interpret this as support for our starting point: deficit, growth rate, and unemployment are jointly determined. A higher unemployment rate is as much driven by lower growth as a lower primary surplus.

The empirical literature on fiscal policy and governmental debt faces the issues of the interdependence and endogeneity of revenues, expenditures, and deficits. An important strand of research uses Structural Vector Autoregression (SVAR) models to assess the effects of fiscal policy on output (Blanchard and Perotti 2002; Badinger 2006; Mountford and Uhlig 2009). VARs treat all the variables as endogenous and interrelated. Thus, in empirical analyses endogeneity and interdependencies are addressed, while uncertainty is not considered. We, in contrast, put uncertainty at the center of our analysis.

Issues of uncertainty and endogeneity trouble policy makers at all times. The early 1970s, however, were characterized by an additional factor: a significant structural change in the advanced economies that involved a strong reduction of the nominal growth rate. Senior economic researchers in the 1970s had been accustomed to a 20-year period of nominal growth rates somewhere between 7 and 13%. Yet, when the first oil shock had passed, average nominal growth rates were much lower, and they never returned to the pre-crisis highs. It has taken some years for researchers to realize that the low growth rates were not a temporary phenomenon caused by the unique event of the oil shocks, but by a new equilibrium growth path, which significantly differed from the former one.

Severe and structural changes are hard to detect. Recently the International Monetary Fund (IMF), in its World Economic Outlook, demonstrated this difficulty in its forecasts on the economic performance of Greece (IMF, various issues). From 2009 to 2015, the IMF repeated a very similar forecast: recession for another six months followed by a recovery. We present the forecasts in Fig. 4 in the “Appendix”. Sims (2010), in heralding a new approach that sees “rational inattention” as a specific form of rational expectation with noisy signals, argues that the effects of slow-moving, long-run changes on variables are hard to detect. That holds particularly in times of economic volatility.

It is therefore important to judge policies in the context and information set of their time. To achieve this, we harness the archive of the monthly report of WIFO. Getzner and Behrens (2016) followed a similar idea in their analysis of Austria’s fiscal policy between 1975 and 2013. They exploited the budget speeches in the parliament by the finance minister to study the underlying idea of the budget plans in the context of their time. Getzner and Behrens find that the economic and financial conditions very much shape the tone of the budget speeches. Elements of expansive fiscal policy are found in all recessions, regardless of which party or coalition ruled the country.

3 Theoretical background

Although both future GDP and public debts are unknown and endogenous, they depend to some extent on expectations about future development. That is why forecast errors are important. Here we structure thoughts on these interdependencies in a simple theoretical framework. Two main expectation formation hypotheses dominate expectation modeling: rational and adaptive expectations. The adaptive expectations formation hypothesis assumes that expectations are built on past experiences. Individuals form an expectation by using past expectations and weighted past expectation errors

where \(E_{t} \left( {\hat{Y}_{t} } \right) = E_{t} \left( {\frac{{Y_{t} - Y_{t - 1} }}{{Y_{t - 1} }}} \right)\) is the beginning-of-the-year growth rate expectation for the current year, \(E_{t - 1} \left( {\hat{Y}_{t - 1} } \right)\) is last year’s growth rate expected at the beginning of last year, and \(\hat{Y}_{t - 1}\) gives the realized growth rate last year. Using past expectation formation, we can rewrite (1) as \(E_{t} \left( {\hat{Y}_{t} } \right) = \beta \mathop \sum \nolimits_{i = 1}^{\infty } \left( {1 - \beta } \right)^{i - 1} \hat{Y}_{t - i}\), which gives the adapted growth expectation by weighted past growth rates. The higher the \(\beta\), the faster that expectations adapt. We can rewrite (1) also in terms of the forecast error as \(E_{t} \left( {\hat{Y}_{t} } \right) = E_{t - T} \left( {\hat{Y}_{t - T} } \right) + \beta \mathop \sum \nolimits_{j = 1}^{T} \left( {\hat{Y}_{t - j} - E_{t - j} \left( {\hat{Y}_{t - j} } \right)} \right)\).

In stable times, forecast errors are neither large nor biased in one direction. Expected growth rates do not differ much between the years. We call the resulting stable forecast long-run growth expectation \(E_{l} \left( {\hat{Y}_{l} } \right)\). The long-run growth expectation adjusts if the error term deviates from zero. The error term is an unweighted sum, thus with several errors in the same direction, long-run growth expectation adjusts.

Certainly, past experiences are not the only elements in expectation building. We assume in line with rational expectations that forecasts rely on models that also include other variables expected to be important for forecasting growth rates. Whatever may have been the forecast model used by Austrian researchers, the realized growth rate \(\hat{Y}_{t}\) is equal to the expected growth rate \(E_{t}^{r} \left( {\hat{Y}_{t} } \right)\) plus expectation error \(u\):

If researchers have all relevant information available and use it correctly, the expectation error \(u_{t}\) for the fully informed rational expectations is zero on average. We assume that the rational expectation growth rate can be expressed as deviation from the long-run growth rate \(E_{t}^{r} \left( {\hat{Y}_{t} } \right) = E_{t}^{r} \left( {\hat{Y}_{l} - \rho_{t} } \right)\).

Because we assume that growth expectations are built on adaptive and rational expectation, we model expectation building as given in (3).

The first term on the right side reflects rational and the second term adaptive expectations. The parameter \(\varphi\) is between one and zero and gives the weight between rational and adaptive expectations. The parameter \(\varphi\) provides therefore a weight for “backward” or “forward” looking in growth expectations. We assume that adaptive expectations are built on growth rates only of the last T = 20 years, because it seems unlikely that growth rates of the war period are taken into account. The expectation error \(\hat{Y}_{t} - E_{t} \left( {\hat{Y}_{t} } \right)\) can therefore have a short-term component \(\rho_{t}\) and a long-term growth component \(E_{t} \left( {\hat{Y}_{l} } \right)\), with an adjustment of long-run growth occurring, for instance, after a structural break. How quickly the expectations adjust depends on \(\varphi\) and on the structure of the correction term. In the short run, distinguishing between the correction and the short-run expectation error is impossible. A slow expectation adjustment results in an overestimation of growth rates for the long-run if a structural break brings down the long-run growth rate.

A simple macro-model may help to make clear how GDP forecast errors affect budget deficits. Because the parliamentary process takes a while, expectations about next year’s variables are needed. We assume that government spending \(G\left( {Y,T} \right)\) is a function of GDP-dependent expenditures—such as unemployment and welfare benefits—and GDP independent expenditures \(\left( T \right)\). Government revenues \(R\left( {Y,\tau } \right)\) are a function of GDP and the tax rate \(\tau\). Since public deficit \(\left( D \right)\). is given by \(D = R - G\), the forecasted deficit is:

Public deficit in period t + 1 Dt+1 can be divided into an expected part \(E_{t} (D_{t + 1} )\) and an unexpected one \(\varepsilon_{t}\). The forecast error in the deficit \(\varepsilon_{t} = D_{t + 1} - E_{t} (D_{t + 1} )\) is given by \(\left( {R_{t + 1} - G_{t + 1} } \right) - E_{t} \left( {R_{t + 1} - G_{t + 1} } \right)\). If we assume that the government targets a constant rate s of public debt B to GDP Y, it follows that the debt level B grows with the same rate as GDP Y, i.e., \(\hat{B}_{t} = \hat{Y}_{t}\) and expected deficit in \(t + 1\;E_{t} \left( {D_{t + 1} } \right) = s_{t} E\left( {\hat{Y}_{t + 1} } \right)Y_{t}\), where the expected growth rate \(E_{t} \left[ {\hat{Y}_{t + 1} } \right]\) partly determines the expected deficit. Since government spending also has the autonomous component T, the deficit is not only a function of GDP but also a policy variable. Yet, the forecast error of the deficit \(\varepsilon_{t}\) is proportional to the forecast error of GDP growth ut.

As argued above, the GDP growth forecast error comprises both long-run and short-run errors. We will look at both in the empirical part of the paper. According to (5), the unexplained component of the deficit in t is positively affected by the forecast error ut and the debt level Bt. Without forecast error in GDP growth, the government deficit is such that the ratio of debt to GDP remains constant.

Figure 1 shows Austria’s debt-to-GDP ratio (right axis) and the GDP forecast error ut (left axis) in two versions: as short-run error, i.e., the difference between the expected and the realized growth rate, and as long-run error, i.e., the difference between the realized growth rate and its 5-year moving average, for the years 1960–1974. Because the long-run growth rate is not “directly” visible, we use the varying five-year moving average of the real growth rate as (noisy) proxy for the long-run rate.Footnote 4

Over the period starting in 1960, the debt-to-GDP ratio was almost constant at around 16%. In periods of economic slowdown, i.e., periods with expected growth rates below the moving average, the public debt rate went up. In good times, i.e., when the growth rate exceeded the long-run growth rate, the debt-to-GDP ratio went down. Thus, over the cycle, the public debt ratio remains constant in the long run if the government targets a constant debt-to-GDP ratio s* and if the underlying natural growth rate does not change.

The situation changes significantly if the long-run growth rate changes as in Austria in the mid-1970s. Figure 2 shows the forecast errors and the debt-to-GDP ratio for the decade after the first oil price shock. The long-run growth forecast error was negative in most years. The nominal growth rate, steadily above 10% before 1974, fell to slightly above 5% until the late 1980s. In one out of 11 years between 1974 and 1984, in 1979, realized growth matched the five-year average. In all other years, growth fell short of this proxy for a long-run growth rate. Consequently, the debt-to-GDP ratio increased significantly over this period. Yet, as argued above, the structural break was hard to detect in these volatile times, and learning therefore was difficult.

A comparison of Figs. 1 and 2 illustrates the difference that this caused to the debt-to-GDP ratio. If the government systematically overestimated growth during the oil price shocks, persistent public deficits and increasing debt-to-GDP ratios occurred even if the government targeted a constant debt-to-GDP level. In our setup with incomplete information, it is hard to relate the realized deficit to governments’ objectives without additional information. Yet, the claim of policy failure relies implicitly on the assumption of perfect foresight.

Without structural change, the past weights (\(\varphi\)) in the expectation-building process are irrelevant. If long-run growth changes however, the government’s expectation-building process becomes important for the resulting debt-to-GDP ratios. We assume that the government has a significant adaptive element in its expectation building, i.e., \(\varphi\) in (3) should not be too low. As already discussed, adjustment time depends on \(\varphi\), \(\beta\), and the variance in the short-term growth. A constant ratio s requires of course an autonomous component T that is used to stabilize the debt-to-GDP ratio s. Independent fiscal policy beyond the fiscal maneuvering space generated by a growing economy is impossible if the government goes for a target ratio s*. Only with sufficiently high long-run growth rate \(\hat{Y}_{l}\) new projects can be realized without running into fiscal trouble.

4 Austrian fiscal policy in the Kreisky era

4.1 Forecast errors, budget plans, and realized budgets

The archive of WIFO monthly reports is a great source of economic analyses since the mid-1920s. The analyses reflect not only hindsight but also future projections. When the researchers commented on the budget plan in every year’s November or December issue, they obviously did not know the future, but they included current knowledge and evaluated the budget plan based on this knowledge. Moreover, since the WIFO has been involved in preparing the budget plan, the reports are very informative, detailed, and reflective. We use this useful source to compare governmental budget plans with realizations in order to assess the role of forecast errors in the building up of a sizable debt level in a rather short time period.Footnote 5

We start by illustrating the expectations about the GDP growth path in the early 1970s and consequences for the budget plans at the beginning of the period. Economists at this time saw a growth path with a real growth rate of 4% averaged over the cycle as “natural” (WIFO 1970 12: 509). The December 1970 issue published the medium-run budget plans for the years 1970–1974 as given below. Two versions were published, based on nominal growth expectations of 7 and 9% (Table 1).

The higher-growth scenario includes both higher revenues and higher expenditures. The recapitalization needs are lower than in the low-growth scenario, but not as much as they could be without additional expenditures. We see this as evidence that on the one hand the government implemented enough projects if the resources were there. On the other hand, budget consolidation did not have the highest priority in the early 1970s, which is not surprising given the very low level of public debt. The real situation in the early 1970s proved to be even better than the more optimistic scenario. Growth was high enough to let recapitalization needs vanish, as shown in Table 2. The differences have always been smaller than the additional debt financing at constant debt over GDP ratios.

The lower part of Table 2 shows the low expectation errors in the early 1970s in absolute values and in relative terms if measured as percent of GDP. Apart from the year 1974, the real development was even better than expected when the budget was approved. Compared to the medium-run budget plan from 1970, budgets were raised in line with better economic performance than the one forecasted in the medium-run planning shown in Table 1. Measured relative to the nominal GDP, the debt level fell in the boom years at the beginning of the 1970s. Of course, during economic booms it is not too difficult to keep the budget in line. New (social democratic) projects were introduced. Until 1974, several laws increased public expenditures for health care and education. When economic conditions are weak, as shown for the following years, it is exceedingly difficult to counter-steer (Tables 3, 4).

During the year 1974, signs intensified rapidly that the boom would come abruptly to an end. The oil price shock made its way through the European economies, sending them into the first severe recession in decades. Austria could not isolate itself from this development, and the 1974 forecast for economic performance in 1975 became pessimistic.

Remarkably, within one year the forecasted real growth rate in 1975 fell by 6.5% points to a forecasted negative growth rate of 2.5%. A budget that is approved in October 1974 must be out of line with 1975 developments if they cannot be foreseen. Revenues (75% of which are taxes) cannot increase in line with the revenues planned in the approved budget.

With the usual model assumption of rational expectation, we would consider growth forecast errors to be zero. However, between 1974 and 1983, Austrian growth forecast errors seem to have had a strong bias. Matching forecasted growth rates with realized ones indicates that time was needed for forecasts to adjust to the realized growth rates. In particular, the late 1970s were difficult times for growth forecasters. The effects of the oil shock and large-scale national recovery packages on real growth and inflation rates were quite difficult to estimate. Given the turbulent times, it is not very surprising that growth rates’ ups and downs were hardly anticipated, even for a short forecast period.

Because budget plans rely on GDP growth expectations, budgets failed to correctly predict deficits if GDP growth forecasts differed from realized growth rates (see Eq. 5). Particularly in the two severe crises following the oil crisis of 1973 and 1979, the budget deficts arose from both the revenues and expenditures sides, each of which was under pressure. Both oil price shocks were not foreseen (and could not have been), which resulted in budgets that did not fit the economic needs. Because we do not have Austrian tax forecasts, we present German changes in tax forecasts instead. They are given in percentage changes and should therefore give an impression of the huge change in government revenue in this severe crisis. The absolute numbers are about one magnitude smaller for Austria, but the ratios are in line with Austrian figures.

Within the time period from June 1974 to August 1975, the expected tax revenue for the year 1975 was reduced by 12.0%. Because government spending cannot be cut by the same rate in this short time period, a deficit must result. We do not have similar data on Austrian tax forecasts, but a reference that tax forecasts had become more difficult after 1974 is given in a discussion of the approved budget of 1983 in the November 1982 issue of FIWO’s Monthly Report.

Figure 3 shows the approved budgets of given years (approved in parliament in September/October of the previous year) and the realized budgets. As seen for GDP growth expectations, the budget forecasts adjusted relatively slowly to changed circumstances. Combining Figs. 2 and 3 illustrates the general tendency that overestimating GDP growth rates corresponds to underestimating of the budget deficit, and vice versa.

Huge discrepancies between the approved and the realized budget are the consequence of the shocks and the resulting forecast errors. Table 5 reports approved and realized budgets from 1975 to 1983.

With the exception of 1977 and 1980, the surprise has always been negative: the realized deficit was higher than the approved one. (See also Fig. 3.) Politics reacted accordingly by reducing or even reversing the deficit surprise in the following year. Yet these were only short-run stabilizations. In the third year after each surprise, at the latest, there was the next negative surprise to the budget. Mid-term smoothing did not work at this time. In sum, the differences between the realized and the approved budget, i.e., the short-run forecast error, amounted to 7.9% of the GDP, which accounts for roughly a third of the total increase of 25% points of the debt-to-GDP ratio between 1975 and 1983.

4.2 Long-term policy goals and the budget

In times of strong negative exogenous shocks, as in the mid-1970s, stabilization is at the center of a government’s economic policy. Yet, looking at the data and reading the WIFO monthly reports commenting on the Austrian budgets, excessive fiscal policy to fight the recession was not the dominating issue. Restructuring expenditures toward those with particularly high multipliers was discussed, but the consequences for the budget were not always taken into account. Yet, Kreisky’s quote comparing the negative effects of public debt and unemployment is closer to an ex-post defense of his policy than a reflection of the actual actions taken.Footnote 6 It is therefore also argued that Kreisky’s long-run projects, which started before the crises and did not stop when the first oil price shock turned into a severe recession, had an even larger effect on the budget in the longer run than stabilization policy. Again, these policies should be judged in the context of the time.

In the general perception at this time, the long-run, business-cycle-smoothed real growth rate was about 4%. Long-run growth was therefore vastly overestimated for a while, until this expectation error was corrected. The difference between long-run growth before and after the crisis is significant in economic and statistical terms, as we show in Table 8. In the language of the theoretical part, \(E_{t} \left( {\hat{Y}_{l} } \right)\) was too large, and ut in (3) was therefore negative. From this follows a negative unexpected effect on government budget \(\varepsilon_{t}\), as we argued in the discussion of (5). This increased public debt \(B_{t}\) and the debt-to-GDP ratio \(s_{t}\). It is impossible for us to know how politics would have accounted for the increase in the debt-to-GDP ratio if the structural break in the long-run growth rate could have been foreseen.

Yet, to give justice to politics at this time, it is important to see that politicians, economists, and civil servants in the ministries worked with a long-run real growth rate of about 4% when planning long-run projects. Because we have only a few long-run growth projections for Austria, which we present in Table 6, we must again look at Germany to verify the impression reached by looking at the Austrian data.

For Germany, the working group for tax forecasts published its assumption about the expected nominal growth rate in each issue. We present this data in Table 7. Comparing the expectations from different forecast times gives a clear picture of slow adjustment to long-run growth expectations in Germany after 1974. Together with the Austrian data, this supports the impression that the fall in the average nominal growth rate in Austria from 13.3% (1970–1974) to 8.7% (1975–1983) was not foreseen.

Two things are worth noting: (i) in every year the nominal growth rate was lower than predicted four years before, and (ii) the long-run (four years ahead) prediction for the nominal GDP growth rate fell steadily from 9.4%, predicted in 1974 for 1978, to 6.9%, predicted 1978 for 1982. It continued to fall to 6.6%, predicted in the 1982 forecast for 1986.

The structural break in the real growth rate that we used to explain the difference (Figs. 1, 2) has so far only been stated. Therefore, Table 8 presents econometric support, in percentages by year, for each structural break in the time series of GDP growth. The analysis uses data from 1955 to 2011. For government revenues, government expenditures, and gross public debt (all in percent of GDP) in Austria in the mid-1970s, the same or a very similar break point can be found.

The Chow test assesses equality of the means of the growth rate for two sub-periods, i.e., before the beginning of the year given in the first row and after. For all possible break points, the F-test rejects equality of the growth rates in the two sub-periods. The structural break in 1975 explains the data best. We therefore find the story supported, and a break in the long-run growth rate is very likely to have affected the forecasts. The change in the real long-run growth rate is drastic. On average, the Austrian economy grew on a real basis at 5.35% before the break in 1975 and at 2.23% thereafter. This undetected change in real growth resulted in a systematic overestimation of GDP growth, i.e., E[ut] < 0, which leads to \(E\left[ {\varepsilon_{t} } \right] < 0\), and therefore a larger deficit than a targeted debt-to-GDP s* would require.

With a given approved budget and a target level of s* = 0.2 for the debt-to-GDP ratio, a fall of the real long-run growth rate by 2% points would increase the debt-to-GDP ratio by 0.4% points every year, according to (5). In 10 years, this adds up to 4.5% points. Lower unforeseen real growth would have amounted to 4.5% points of the debt-to-GDP ratio, which is a fifth of the total increase in this ratio during the Kreisky era. This results only from the forecast errors. We have not changed our assumption that policy makers would have targeted an unchanged debt-to-GDP ratio of 0.2, which was the level in the early 1970s.

4.3 Discussion of the result

Pure public debt data supports Austria’s collective memory of Kreisky as the “Debt Chancellor.” It is widely agreed that Kreisky’s lax fiscal policy and in particular his Keynesian policy during the recession caused the fast rise in public debt. But we question the rest of the collective story. We argue that this “Debt Chancellorship” was at least as much a historical accident as it was caused by ideology and Kreisky’s patronizing policy. Two findings support our view: first, the government did relatively little to fiscally lean against the recession; second, projects that are usually considered as symbols for Kreisky’s lax fiscal policy (education reforms, infrastructure projects, etc.) would not have seemed that financially unrealistic when they were approved, in an era of nominal growth rates far beyond 10%. The long-term projects that are the legacy of the Kreisky era, such as reforms in education, health, and social security, were planned and discussed in the parliament when the economy was growing by 13% per annum on average. Moreover, being set up to improve human capital, these reforms could have been expected to be growth-enhancing in the long run. The comparison of debt rates across time is not enough to judge the success of these policies. One would need the counterfactual situation of Austria without these reforms as a benchmark—for which data are of course not available.

The important role of government investment in infrastructure and human capital is intensively discussed in the growth literature (see for instance Barro and Sala-i-Martin 2003). It is beyond the scope of this paper to dive into this literature. We nevertheless want to state that there is an active role for governments to play, which lies particularly in the provision of public infrastructure and support for human capital formation, both being central in Kreisky’s long-run policy goals.

Here we are back to the interdependence of governmental budgets and GDP, now in the long-run growth context. Austria did not only manage to overcome the oil crises and the structural change in its economy at the end of the 1980s; it turned to long-lasting, robust growth in the early 1990s, which held for 20 years. A well-educated labor force and good infrastructure have been critical for this path. Thus, when judging the debt level, we should also take into account the assets created, accumulated, or initiated in the Kreisky era.

5 Summary

Kreisky’s chancellorship has been ex-post characterized as an era when public debt reemerged in Austria on a large scale. Many observers have held Kreisky’s social democratic and Keynesian ideas responsible for the strong increase of public debt to about 40% of GDP during his reign (1970–1983). This claim is plausible and has been frequently repeated. Yet it is hard to reconcile with the data. We found little evidence for active stabilization policy.

We propose a different view of this era. We see the strong increase of public debt as short-run and long-run forecast errors that resulted from a very volatile episode that hid a significant structural break, which was unforeseen by contemporary policy makers. We presented evidence that the short-run forecast errors, i.e., the differences between the approved budgets in September or October of the previous year and the realized budgets, explain about one-third of the debt increase. This sizable share is driven by proximity to the two oil price shocks and the successive recessions. Calmer years showed a tendency of the budget to return to being balanced. The medium-run balancing effect over the cycle, however, was not strong enough to equalize the debt increases from the recession years, because of the long-run structural break, which has not yet been taken into account. Assuming an unchanged debt-to-GDP target rate, the long-run growth slowdown increased the debt-to-GDP ratio by at minimum 4% points. This amounts to a fifth of the total increase in the ratio during the Kreisky era. We find the forecast errors jointly to account for one-half of the total increase in the debt-to-GDP ratio during the Kreisky years.

Notes

We use the term “policy failure” as a collective term to describe very different claims, including clientele politics, opportunistic behavior, short-sided power politics, inappropriate stabilization policy, and the political business cycle.

The German original reads: “Und wenn mich einer fragt, wie denn das mit den Schulden ist, dann sag ich ihm das, was ich immer wieder sage: Dass mir ein paar Milliarden mehr Schulden weniger schlaflose Nächte bereiten als ein paar hunderttausend Arbeitslose mehr bereiten würden.” Cited in Die Presse, Print Edition, January 22, 2011.

In line with our argument Mauro et al. (2013) assess the outcome of several budget consolidation episodes by comparing the ex-ante announced consolidation plan with the realized performance: They state that consolidation is often caused by lucky circumstances rather than the choice for true adjustment.

Noisy because changes in the real growth rate have many origins other than changes in the underlying long-run growth rate, such as bad luck, economic cycles, appreciations or depreciations, etc.

There is one major obstacle: the various changes in the statistics, groups, categories, and definitions that complicate comparison over time. More detailed information is often ignored for this reason. Yet even at this very aggregated level, neither revenues nor expenditures are completely unaffected by changing definitions and classifications over time.

Hannes Androsch, the minister of finance in these years, confirmed this when discussing our work at the Austrian “Zeitgeschichtetag” in Graz, on June 8, 2016.

References

Badinger H (2006) Fiscal shocks, output dynamics and macroeconomic stability: an empirical assessment for Austria (1983–2002). Empirica 33:267–284

Barro R, Sala-i-Martin X (2003) Economic growth, 2nd edn. MIT Press, Cambridge

Blanchard O (2006) European unemployment: the evolution of facts and ideas. Econ Policy 21(45):5–59

Blanchard O, Perotti R (2002) An empirical characterization of the dynamic effects of changes in government spending and taxes on output. Q J Econ 117(4):1329–1368

BMF (Federal Ministry of Finance) (Several Issues). Tax Forecasts, press releases. http://www.bundesfinanzministerium.de/Content/DE/Standardartikel/Themen/Steuern/Steuerschaetzungen_und_Steuereinnahmen/Steuerschaetzung/ergebnisse-des-arbeitskreises-steuerschaetzungen-seit-1971.html

Bohn H (1998) The behavior of US public debt and deficits. Q J Econ 113(3):949–963

Bohn F, Meon P-G (2009) Political transfer cycles. NiCE Working Paper 09-101

Bröthaler J, Getzner M, Haber G (2015) Sustainability of local government debt: a case study of Austrian municipalities. Empirica 42(3):521–546

Bruno M, Sachs J (1985) The economics of worldwide stagflation. Basil Blackwell, Oxford

Frey B (1976) Theorie und Empirie politischer Konjunkturzyklen. Zeitschrift für Nationalökonomie 36:95–120

Getzner M, Behrens D (2016) Wirtschaftspolitische Paradigmen in der österreichischen Budgetpolitik: Eine Inhaltsanalyse von Budgetreden in Österreich (1975–2013). In: Wohlgemut N, Blüschke D (eds) Wirtschaftspolitik im Wandel der Zeit: Festschrift für Reinhard Neck zum 65. Geburtstag. Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main

Gödl M, Zwick C (2018) Stochastic stability of public debt: the case of Austria. Empirica. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10663-017-9376-4

IMF (International Monetary Fund) (various issues). World economic outlook. www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2017/01/weodata/index.aspx

Mauro P, Romeu R, Binder A, Zaman A (2013) A modern history of fiscal prudence and profligacy. IMF Working Paper No. 13/5, International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC

Mountford A, Uhlig H (2009) What are the effects of fiscal policy shocks? J Appl Econom 24(6):960–992

Neck R, Haber G, Klinglmair A (2015) Austrian public debt growth: a public choice perspective. Int Adv Econ Res 21(3):249–260

Schellhorn F (2011) Bruno Kreisky, der Vater des sündigen Gedankens. Die Presse, Print-Edition, January 22, 2011

Shiller R (2017) Narrative economics. NBER Working Paper 23075

Sims C (2010) Rational inattention and monetary economics. In: Friedman BM, Woodford M (eds) Handbook of monetary economics, vol 1. Elsevier, Amsterdam

WIFO (Austrian Institute of Economic Research) (several issues). Archive monthly reports. www.wifo.ac.at/bibliothek/archiv/MOBE

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by University of Graz. The paper has been written as part of the project “Government debts in the very long-run” financed by the OeNB’s Anniversary Fund. We are very grateful for the support. We thank the participants of the Workshop “Empirical Economics” in January 2016 in Vienna for valuable discussions. We retain sole responsibility for any remaining errors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

See Fig. 4.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Brugger, F., Kleinert, J. The strong increase of Austrian government debt in the Kreisky era: Austro-Keynesianism or just stubborn forecast errors?. Empirica 46, 229–248 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10663-017-9396-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10663-017-9396-0