Abstract

This study contributes to the literature on destination-country consequences of international migration, with investigations on the effects of immigration from new EU member states and Eastern Partnership countries on the economies of old EU member states during the years 1995–2010. Using a rich international migration dataset and an empirical model accounting for the endogeneity of migration flows, we find positive and significant effects of post-enlargement migration flows from new EU member states on old member states’ GDP, GDP per capita, and employment rate, and a negative effect on output per worker. We also find small, but statistically significant negative effects of migration from Eastern Partnership countries on receiving countries’ GDP, GDP per capita, employment rate, and capital stock, but a positive significant effect on capital-to-labor ratio. These results mark an economic success of the EU’s eastern enlargements and free movement of workers in an enlarged EU.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Europe has always been a hub of international migration. In 2010, almost seven out of a hundred EU residents were born outside the EU, and an additional three were born in a different member state than the current state of residence.Footnote 1 The 2004 and 2007 enlargements of the European Union and the extension of the EU’s internal market, including the freedom of movement of workers,Footnote 2 to the new member states from Central and Eastern Europe changed the migration landscape in Europe tremendously. These enlargements abolished the barriers that precluded east–west migration flows during the Cold War, and created an internal labor market for the total population of about half a billion people, cross-cutting boundaries of member states with disparate level of economic development, wages, unemployment rates, and labor market institutions.Footnote 3 Unsurprisingly, these differences lead to significant migration flows mainly (but not exclusively) in the east–west direction. These new migrant flows have not been unanimously welcome in the receiving countries, and immigration from Central and Eastern Europe was one of the pivotal arguments in the debate about UK’s leaving the European Union, commonly known as “Brexit”.

The scale of these flows was indeed remarkable, with about five and half million citizens of the new member states (EU12) living in the pre-enlargement member states (EU15)Footnote 4 in 2010, which constitutes an increase of three and half million, or to a factor of 2.5, over just 6 years.Footnote 5 As this large-scale policy experiment can certainly provide a number of interesting insights into the labor market effects of migration, quite naturally, a significant body of literature studying the repercussions of such migration flows mainly for the receiving but also the sending labor markets has emerged.Footnote 6 This literature has mainly looked at the effects on wages, employment and unemployment, and welfare take up in individual member states separately. Generally speaking, besides some local effects, the available evidence is that the receiving labor markets absorbed post-enlargement immigrants rather seamlessly with statistically or economically insignificant effects on labor market indicators.

This evidence may, however, mask broader consequences of post-enlargement mobility. Migration in general facilitates cross-border social and economic ties, leading to an increased mobility of ideas and technologies, capital, and goods and services and thus a better allocation of production factors and improved total factor productivity, as well as gains from trade.Footnote 7 Although inherently difficult to detect, such effects may significantly affect EU member states, and thus their measurement is important for the debate about EU’s migration policy.

The aim of this study is to analyze the effects of recent east–west mobility on economic outcomes across the EU and in the EU as a whole. Using an empirical model accounting for the problem of endogeneity of migration flows, we look at a range of indicators, in particular at GDP per capita, employment rates, capital stock and total factor productivity (TFP). The analysis is based on a rich dataset of immigration flows and stocks of foreigners, which has been collected by writing to selected national statistical offices, in 42 destination countries from virtually all source countries from around the globe for the years 1980–2010.Footnote 8 We comparatively evaluate the effects of post-enlargement intra-EU mobility (after the 2004 and 2007 enlargements) as well as immigration from the Eastern Partnership (EaP) countries on a subsample consisting of EU destination countries.Footnote 9

The main contribution of this study is twofold. First, the massive post-enlargement migration flows over a relatively short period of time offer a unique framework that is worth exploring in order to inform the academic debate about the broader economic effects of migration and migration policy. Second, a comparative analysis of the costs and benefits of mobility under various migration regimes is much needed, in light of the heated policy debates surrounding migration policy in the EU. This agenda has become ever more urgent in view of the EU’s plans to upgrade its mobility framework within its Eastern Partnership program and an increased migration potential from some of the key source countries as a consequence of the recent events in EU’s neighborhood including the Arab Spring events, the Syrian civil war of the 2010s, and the Ukrainian crisis that started in 2014.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the theoretical and empirical literature relevant to our study. Section 3 briefly describes the novel international migration database and other variables important for our analyses and provides some descriptive statistics. Section 4 presents an empirical model on the impact of immigration on the destination country’s economy, on which we base our analysis, and our identification strategy. We discuss the results of econometric analyses in Sect. 5. Finally, Sect. 6 concludes, providing a discussion for future steps in our research.

2 Literature review

The effects of immigration on receiving countries has been a much debated issue in economics for a long time. Early theoretical models on the effects of labor mobility considered immigration in an extended version of the traditional Solow–Swan model, where immigrants are assumed to increase a country’s unskilled population, which ceteris paribus leads to a lower per capita income because of a reduction in capital. Benhabib (1996) relaxes the assumption of the Solow–Swan model that immigrants do not provide any capital, which leads to some economic gain from immigration in terms of per capita GDP. Borjas (1995) argues that immigrants increase labor endowment in receiving countries and the new internal equilibrium is then characterized by a lower national wage, higher employment and higher national income. The difference with respect to the initial equilibrium is the so called “immigrants surplus” (Borjas 1995). A study by Hanson (2008) analyzes welfare consequences of immigration by assuming heterogeneity of workers in terms of skills, and perfect substitutability between native and foreign-born workers. The author shows that when low-skilled workers are allowed to freely move between countries, there will be migration from low-wage countries to high-wage countries until the wages will equalize. In the receiving country, home-born unskilled workers lose while the native high-skilled workers win in terms of welfare (surplus). Thus, so far, the theory says that the effect of migration depends on the type and selectivity of immigrants. Besides substitutability or complementarity of immigrant and native labor, capital endowments play an important role: if the physical capital endowment provided by immigrants is lower than the average native capital endowment, the effect of immigration will be negative in terms of per capita GDP. From the empirical point of view, the question of immigration’s economic impact is thus still open.

Most of the existing empirical papers examine the impact of immigration by focusing only on labor market implications and on one or only a few receiving countries (e.g. Aydemir and Borjas 2007; Borjas 2003; Ottaviano and Peri 2008; Manacorda et al. 2012). Angrist and Kugler (2003) use a panel of European countries and analyze the labor market effects of immigration. Related to this paper, Peri (2008) and Gonzalez and Ortega (2011) analyze the effects of immigration on employment, capital accumulation and productivity, respectively, across US states and Spanish regions. The literature on the aggregate effects of migration using cross-country panel analysis is very scant. From earlier contributions, Dolado et al. (1994) found a negative effect of immigration on per capita income growth, so they argued that this was due to the fact that immigrants in OECD countries have lower human capital than natives. Recently, the aggregate effects of immigration have been discussed by a number of studies by Giovanni Peri, and a general overview can be found in Peri (2016). For instance, Peri (2012) analyzes the effects of immigration on each input of production function and on total factor productivity (TFP) for U.S. states’ economies. The author also discusses the potential endogeneity problem, which he solves by using the instrumental variable (IV) technique, with past settlement patterns of immigrants driven by proximity to the border as an instrument for gross migration rates. In particular he shows that an increasing immigration leads to: (1) zero crowding out of the employment of natives (2) an increasing TFP growth. Felbermayr, Hiller and Sala (2010) investigate the effect of immigrants (by using the stock of immigrants in a destination country) on per capita GDP in the host countries. Using an IV cross-sectional approach and controlling for institutional quality and trade and financial openness, they find a positive effect of immigration on per capita GDP: a 10% increase in the migrants stock leads to a 2.2% increase in per capita GDP. Similarly, Bellini et al. (2013) find that the share of foreigners in the total population has a positive effect on per capita GDP in EU destination regions.

Further, Peri (2007) argues that immigrants’ and natives’ skills are not perfectly substitutable,Footnote 10 which creates the incentive for natives to specialize in more skilled jobs (e.g. more intensive in communication and language tasks)Footnote 11 and let the immigrants to do the manual tasks (Peri and Sparber 2009). This finding is consistent with other immigration studies that show immigration does not crowd out natives, but in fact it has a positive effect on employment and investment (Ortega and Peri 2009; Kahanec and Zimmermann 2010), while total factor productivity is increased by optimizing task specialization and by encouraging the adoption of unskilled-efficient technologies (Peri 2012).

In an earlier paper, Peri (2006) argues that although immigration increases employment for the natives with complementary skills, it has a negative effect on those with substitutable skills. Previous research also shows that immigrants are substitutes for work performed by migrants that came in earlier migration waves. In particular, using data from different countries and different econometric methods, they highlight that immigration increases the overall wages for natives in the host country, but reduces the wages of previous immigrants (Ottaviano and Peri 2012; D’Amuri et al. 2010; Docquier et al. 2013; Longhi et al. 2010). A recent study by Foged and Peri (2016), however, shows that even if immigrants may be imperfect substitutes to low-skilled workers, they still improve their labor market position. The reason is that, as a reaction to the migrant inflow, low-skilled native workers had moved to complementary job market areas and started to specialize in non-manual skills. This leads to an increase in their wages and employment opportunities (Foged and Peri 2016). However, in contrast to the hypothesis of imperfect substitutability of immigrants and natives, Docquier et al. (2013) find that immigration increases wages. On average, it has a negative effect for highly educated workers (except for the US) and has a positive effect for the wages of low-skilled workers.

From other outcome variables, it is worth mentioning that immigration appears to have a positive effect on trade creation, by reducing the fixed costs of trade, through network effects, and stimulates the trade of differentiated products (Peri and Requena 2010), and on increasing foreign direct investment (Javorcik et al. 2011; Gormsen and Pytlikova 2012). The effect on services is also positive, in the sense that it decreases the prices for low-skilled services (e.g. gardening, house-cleaning), which benefits the natives (Longhi et al. 2010). Regarding the effects of immigration on education, some previous studies suggest that the increase in the number of foreign students has a negative effect on the education of natives, while it increases the knowledge creation for universities (Hanson 2008; Kato and Sparber 2013). Using a panel of EU member states, industries and skill-groups, Guzi et al. (2015), document that immigrants are more responsive to labor and skill shortages than natives, contributing to economic efficiency in the receiving countries. Kahanec and Zimmermann (2014), argue that immigration tends to reduce income inequality.

When it comes to the effects of post-enlargement migration on receiving countries, the consensus in the literature appears to be that there was very limited, if any, effect on wages or unemployment rates (see Kahanec and Zimmermann 2010, 2016; Gilpin et al. 2006; Blanchflower et al. 2007; Lemos and Portes 2008). Doyle et al. (2006), Hughes (2007) and Barrett (2010) report that even in Ireland, with the highest relative inflows from the new member states, effects on the aggregate unemployment rate could not be detected, although some substitution might have occurred. Brenke et al. (2010) point at competition for low-skilled jobs between the immigrants from Central and Eastern European (CEE) states that entered the EU in 2004 (EU8), and immigrants from outside of Europe. Similarly, Blanchflower and Lawton (2010) report some substitution in low skilled sectors. Blanchflower and Shadforth (2009) and Blanchflower et al. (2007) argue that it was the fear of unemployment that resulted in some wage moderation in the UK prior to the 2004 enlargement. Several authors, including Kahanec and Zimmermann (2010, 2016), Kahanec et al. (2013), Giulietti et al. (2013), or Barrett (2010) have proposed some positive macroeconomic effects of post-enlargement mobility within the EU. The latter study, for example, argues that increased immigration from the new member states fueled the Irish economy and boosted its GNP growth during the boom preceding the Great Recession. However, empirical analyses using more general multi-country data to investigate this hypothesis are missing. Even less is known about the possible effects of immigration from EaP countries.

This paper contributes to the literature by providing empirical estimates on the effects of immigration on total GDP and GDP per capita, aggregate employment, capital stock, productivity and, consequently, income per capita at the country level by focusing on the recent large immigration flows from Central and Eastern Europe to the EU15.

3 Data description

The dataset on international migration used for the analyses was collected by Mariola Pytlikova and encompasses information on bilateral flows and stocks of immigrants from 42 destination countries over the period 1980–2010.Footnote 12 The dataset had been gathered by requesting detailed information on migration inflows and foreign population stocks by source country from selected national statistical offices in 27 countries. For six other countries—Chile, Israel, Korea, Mexico, the Russian Federation and Turkey—the migration data comes from the OECD International Migration Database. For nine other destinations—Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Romania and Slovenia—the data is collected from Eurostat. For the purpose of our analysis, we have used data on foreign population stocksFootnote 13 and have focused on EU15 and EU27 as destination countries and the EU12 and EaP as sending countries, for a time period ranging from 1995 to 2010.Footnote 14 As concerns the number of observations on foreign population stocks across all EU27 destination countries, the data has become more comprehensive over time, and thus missing observations have become less of a problem in more recent years. Compared to other migration data sources, our data is more comprehensive, for most countries have annual information on current stock of migrants and had kept such records for a relatively long time-period. In our dataset, as in the other existing datasets, different countries use different definitions for an “immigrant” and draw their foreign population statistics from different sources. While some countries report country of birth definition, which is preferred in our data, other countries use the definition by citizenship or country of origin, which includes the second or third generations of immigrants, excluding the naturalized ones. In the process of data gathering, the definition of country of birth was prioritized whenever possible. The main reason was to avoid problems related to the naturalization of foreigners, which can range significantly across countries, and therefore relying on definition by citizenship would lead to measurement issues. Although for the vast majority of destinations in our data we use country of birth definitions, for some destinations we have only data by citizenship or country of origin, see Table 4 in Appendix 1 for an overview of definitions and sources of the foreign population data. This may induce some measurement issues; see Pedersen et al. (2008), Adserà et al. (2015) and Cai et al. (2016) for a discussion. Unfortunately, two important European destinations, Germany and the Netherlands, did not provide data by country of birth.Footnote 15 We acknowledge that using migration data by country of nationality for these two countries may induce some measurement issues, which we address in the analyses, at least partly, by including country fixed effects. The information on other economic and social factors for these countries has come mostly from the World Development Indicators (WDI) by the World Bank, and part from sources such as OECD, ILO, or IMF.

3.1 Descriptive statistics

Compared to other advanced economies, labor mobility is relatively low in the European Union. Gill and Raiser (2012) report that the annual interstate mobility of working-age population in the EU15 was about 1% before the 2004 enlargement. The corresponding rate for the US was 3%, Australia and Canada 2%, and even the Russian Federation exhibited only 1.7%. In southern Europe, mobility rates are even lower at about 0.5% annually, whereas countries like France, Ireland, the Netherlands or the UK report mobility rates of around 2% (Bonin et al. 2008).

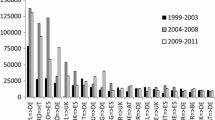

Most migration in Europe happens among EU member states; inflows from Eastern Partnership (EaP) countries to the EU had been increasing before the onset of the Great Recession, but remain much below those from other source regions. Figure 1 describes migration flows into EU countries, by continent of source countries. As can be seen, the biggest migration flows come from Europe, followed by Asia and Africa. Figure 2 allows for a closer look at the migration flows from Europe. We divide the source countries of foreigners into the “old” EEA/EFTA18 countries, EaP countries and EU 2004 and EU 2007 entrants to the EU.

Source: Gross inflows. Own calculations using collected migration flows and stock database by Pytlikova (2011)

Migration flows to EU27 destination countries by regions of origin, 1990–2010.

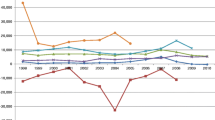

Source: Gross inflows. Own calculations using collected migration flows and stock database by Pytlikova (2011)

Migration flows to EU27 destination countries from Europe, by European regions of origin, 1990–2010.

Figure 2 shows that the highest numbers of immigrants come from the “old” EU/EEA/EFTA18 source countries and their inflows are relatively stable over time, whereas the lowest immigration into EU27 destinations stems from the EaP source countries.

Figure 2 also shows the consequences of happenings in the European history such as the break up of the former Soviet Union and the EU enlargements towards the East. The 1992 peak of migration from “Other European source countries” region corresponds to the development in migration surrounding the fall of the USSR, and also partly covers the flow of refugees from the former Yugoslavia following its ethnic conflicts starting in 1991. Also, one can observe a gradual but considerable increase in migration flows for the new EU 2004 entrants after the first wave of EU’s eastern enlargement in 2004. Similarly, migration from Bulgaria and Romania increased sharply after the 2007 EU enlargement. The decline after 2008 for all countries most likely corresponded to the financial crisis, which began to affect Europe in that year.

Looking at the evolution of migration stocks by continents of origin, we may observe that migration trends follow the development of the migration flows closely. European countries provide the highest number of migrants, followed by Asia and Africa, see Fig. 3.

Source: own calculations using collected migration flows and stock database by Pytlikova (2011)

Foreign population stocks living in EU27 destination countries by regions of origin, 1990–2010.

Similarly as in the case of immigrant flows, we divided the foreign population stocks stemming from Europe into more detailed regions of origin (see Fig. 4). We observed that the highest number of migrants living in EU27 countries originally came from the “old” EU15 countries and Norway, Iceland and Switzerland (“old” EEA/EFTA18), whereas foreigners stemming from the EaP countries have the lowest numbers. Still, it can be seen an upward trend, suggesting future increases in the stock of migrants from EaP countries.

Source: own calculations using collected migration flows and stock database by Pytlikova (2011)

Foreign population stocks living in the EU27 destination countries from Europe, by European regions of origin, 1990–2010.

Transitional arrangements applied differently across the EU towards citizens of new member states. This and other factors such as linguistic proximity or labor market performance resulted in significant variation in terms of the intensity of migration flows across destination countries. As consequence, stocks of foreign population vary across EU destinations markedly. Whereas circa 2010 the main target countries for EU8 citizens were the UK and Germany,Footnote 16 relatively few of them lived in Malta, Bulgaria or Slovenia (see Table 1). Italy and Spain dominated as the most attractive destinations for the immigrants from Bulgaria and Romania (EU2), while the EU8 countries were mostly at the other end of the range. Migrants from EaP countries predominantly live in Italy, Germany, but also in Poland and the Czech Republic. Countries such as Malta, Finland, Slovenia and the Netherlands are the least popular destinations among the EaP migrants (see Table 1). We may observe that there was only a slight increase in the share of immigrants from the EaP countries in the EU destination, from 3.36 to 3.58% immigrants from the EaP in total immigration in 1995 and 2010, respectively.

The effects of immigrant inflows very much depend on the skill composition of immigrant inflows. Although the data does not generally permit a detailed account of the variation in skill composition across destination countries, previous literature using micro-data indicates that migrants from the new EU member states appear to have been predominantly medium skilled, but with rather high proportions of high skilled individuals (Kahanec and Zimmermann 2010; Brücker and Damelang 2009). Brücker and Damelang (2009) reported that the share of high skilled individuals was 27% among EU15 natives, 22% among EU8 immigrants, and 18% among EU2 immigrants. The corresponding figures for low-skilled migrants were 27, 17, and 29% respectively. Although EU8 migrants appear to be relatively skilled, we should note that many of them have worked in occupations below their level of formal education, which probably affected their impact on the labor market (Kahanec and Zimmermann 2010). As for the cross-country variation, Holland et al. (2011) report that Luxembourg, Denmark, Sweden, and Ireland exhibit the highest shares of high-skilled workers from the new member states, whereas Portugal, Spain, Belgium, Netherlands, and Finland disproportionally attracted their lower-skilled colleagues. According to Kahanec (2012) migrants from the EaP countries appear to have been the least educated of the three immigrant groups considered in this study, and have been similarly pushed to downskill into lower skilled jobs.

Table 2 provides baseline statistics for the key variables used in our analysis. We observe the well-known gap in GDP per capita between the EU15, EU8, and EU2 countries, with the EU15 being the most affluent and the EU2 the least affluent regions, with EU8 countries in between.

Similar patterns can be observed for output per worker. As for the employment rates,Footnote 17 the gaps seem to much less significant. The table also shows, that EU15 is the most capital-abundant region of the EU, with EU8 and especially EU2 workers being equipped with significantly lower capital. On the other hand, growth in capital-to-labor ratio is the highest in the EU2, and the lowest in the EU15, with the EU8 in between.

Figure 5 documents the evolution of GDP per capita during the period 1995–2010 for five major blocs of EU members: northern, southern and western EU15 members, EU10, and EU2. We observe significant gaps between the five blocs, but also convergence of EU10 new member states with respect to the EU15, growing gaps within the EU15, and growing but lagging EU2. The effect of the Great Recession after 2008 is clearly visible.

GDP per capita, PPP, constant international $, period of 1995–2010. Notes Figure based on data from WDI. Regions are defined as follows: Northern Europe: Denmark, Finland, Sweden; Western Europe: Austria, Belgium, Luxembourg, Germany, Ireland, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and United Kingdom; EU 10: Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Slovakia and Slovenia; EU2: Bulgaria and Romania

In Fig. 6 we visualize unemployment patterns across the same five blocs of countries. The variation across the blocs and over time is much larger than for GDP per capita. Western and Northern European blocs exhibit the lowest unemployment rates in the EU. Southern Europe, the EU10, and EU2 countries, on the other hand, exchange positions in the ranking of blocs by unemployment rate several times over the studied period of time. All blocs share the same pattern of decreasing unemployment rates before the Great Recession, and increasing unemployment during the Great Recession. One exception is the EU2, which went a period turbulent times and increasing unemployment in the late 2000s. The EU10 and Southern Europe exhibit the steepest increase in unemployment rate since 2008.

Unemployment rate in %, period of 1995–2010. Notes Figure based on data from WDI. Regions are defined as follows: Northern Europe: Denmark, Finland, Sweden; Western Europe: Austria, Belgium, Luxembourg, Germany, Ireland, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and United Kingdom; EU 10: Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Slovakia and Slovenia; EU2: Bulgaria and Romania

4 Methodology

To determine the effects of immigration from new EU member states and from Eastern Partnership Countries on the receiving EU economies, we depart from an aggregate production function framework in our analyses, similarly as in Peri (2012), Ottaviano and Peri (2012) and Docquier et al. (2013). In our analyses, we investigate effects that immigration has on wages (as proxied by GDP per capita, PPP, given the usage of aggregate data) and economic growth rate, as well as on total employment, physical capital, total factor productivity and the capital to labor ratio. In other words, we are estimating the following set of models:

where X represents one of the following: employment rate and labour force participation (to account for the labor input), capital services and capital to labor ratio (to account for the capital input), total factor productivity (calculated as the Solow residual), output per worker (as a proxy for the average wage) and output per capita. To capture other factors determining the economic outcomes of our interest that cannot be attributed to the changes in stock of foreigners per population, we account for country-specific time-invariant characteristics, represented by the term υ j , time fixed effects θ t , as well as time fixed effects interacted with region dummiesFootnote 18 in our main specifications, δ r θ t . Finally, ɛ jt represents the robust error term clustered by country. The explanatory variable of our interest is foreign population stock S from particular regions of origin relative to the total population P in destination country j, \( s_{jt} = \frac{{S_{jt} }}{{P_{jt} }} \). Thus, the effects of immigration on the destination country economies are captured by coefficient γ.

We hypothesize that foreign population can affect the aggregate production of the receiving country. In particular we expect that, first, immigrants increase the total labor supply and may at the same time either crowd-out some natives or attract them into employment (especially if they provide jobs complementary to those of natives and stimulate productivity and specialization, or enable natives to enter the labor market by providing household services). We therefore estimate immigration’s total effect on employment, which combines their direct contribution and the effect on native employment. Second, we expect immigration to affect investment, as the marginal product of capital may be increased due to the increase in labour supply. In addition, depending on the skill composition of immigrants, the effect on capital accumulation and capital intensity can be positive, as highly educated immigrants may work in more capital-intensive sectors, or may use capital-complementary techniques. On the other hand low–skilled immigrants can have a negative effect on capital, or leave it unaffected. Thus, the impact on capital accumulation and capital intensity in the short and long run depends on the composition of immigrants. Finally, immigrants may either give rise to crowding out effects; given fixed factors of production (acting as substitutes), and/or they may add to the varieties of ideas and products in the receiving economy (acting as complements); depending on which effect prevails, this may result in a higher or lower total factor productivity.

4.1 Identification

A methodological problem that arises from the models described above is the problem of simultaneity or reverse causality. It may well be the case that immigration rates are influenced by the dependent variables (low employment, or low GDP triggering migration flows), and not the other way around. To deal with the potential endogeneity problems, we apply the instrumental variable (IV) technique in our analyses, in which identification of causal effects rests on the instrumental variable. To qualify as a good instrument, a variable has to meet two conditions. First, it must be uncorrelated with the error term of the structural model and, second, it must be correlated with the endogenous variable.

As an instrument, we use a predicted foreign population rates, which we construct from predicted stocks of migrants obtained based on using a model of determinants of bilateral migration. In our two-stage strategy, the first-stage model of migration determinants has the following form:

where s ijt stands for the share of foreign population originating from country i and living in country j at time t. On the right hand side we include an interaction of origin country fixed effects and time dummies, λ i θ t , to account for any economic, demographic or social changes in origin countries in each year and a set of bilateral country-pair specific effects, δ ij . Based on the model we predict foreign population stocks, which are then summed by each destination country and adjusted for the population size of each particular destination country. The resulting variable is used as an instrument for the structural equation in the second stage. Hence, for our identification strategy, we assume that development in home countries represented by the interaction of the origin country dummies and time is uncorrelated with economic conditions in destination countries (i.e. with our dependent variables that we use in the second step), and at the same time those push factors represent strong predictors of international migration (Adserà et al. 2015; Palmer et al. 2015).

5 Results

The results of our analyses of the effect of immigration on the EU15 economies are presented in Table 3. We report each model estimated by the OLS method with country fixed effects (FE) and by the instrumental variable technique with country fixed effects (2SLS-FE), which accounts for possible endogeneity of migration flows. The rows correspond to models with the GDP per capita (to account for the average wage) and total GDP (both PPP adjusted), the employment rate and labor force participation (to account for the labor input), capital services and capital to labor ratio (to account for the capital input), and total factor productivity (calculated as the Solow residual), and output per worker (to account for productivity) as dependent variables. To account for possible differences across immigrant categories, as defined by their origins, we distinguish the results for foreigners stemming from the 2004 EU entrants, 2007 EU entrants, and EaP countries.

A number of notable results emerge in Table 3. Whereas fixed-effects OLS models (FE) generally produce insignificant results, relatively small, but negative and statistically significant, effects on GDP, GDP per capita, capital-to-labor ratio, and output per worker emerge for immigration from the EaP countries. Due to possible endogeneity of migration flows, our preferred specification is the instrumental variable (2SLS-FE) model. Here, we believe that the variation in the expected stocks of migrants from EU 2004, EU 2007 and EaP countries is reasonably exogenous conditional on origin country fixed effects and time dummies, and bilateral country-pair specific effects as noted in Eq. (2) above. In Table 3 we report the weak-identification Kleibergen and Paap (2006) F-statistic. As we can see from Table 1, the value of F-statistics exceeds the Stock and Yogo (2005) weak-identification critical value of 16.38 (for 10% maximal size distortion) for immigration from EU 2004 entrants and from EaP countries, whereas it is lower for immigration from EU 2007 entrants. This suggests that our instruments are strong for model specifications for immigration from EU 2004 and EaP group of countries, whereas the instrument is weak for effects of immigration from EU 2006 entrants.Footnote 19

In 2SLS-FE regressions, we observe a statistically significant positive effect of immigration from the new EU countries on GDP and GDP per capita in the EU15 destination countries, whereas the coefficient for immigrants coming from EaP countries is negative. The estimated effect on GDP per capita is quite large as the coefficients imply that a 10% increase in the number of immigrants coming from the 2004 and 2007 EU member countries per destination population increases the destination’s GDP per capita by 0.3 and 0.55%, respectively. In contrast, a 10% increase in share of immigrants coming from the EaP lowers GDP per capita in the EU15 countries by 0.13%. Whereas in the FE regressions, there is some evidence that an increase in the shares of foreigners from new EU member states increases labor force participation (at a 10% level of significance), in the 2SLS-FE regressions, the coefficients are no longer significant. The positive effect of immigration from new member states on the employment rates is documented in the 2SLS-FE regressions; however, a small, but negative and statistically significant, coefficient emerges for immigrants from EaP countries.

No statistically significant results emerge in the 2SLS-FE models for the effects on total factor productivity. The same applies to the impacts on capital stock and the capital-to-labor ratio for immigration from the new EU member states; however, for immigrants from the EaP countries, a small negative effect on capital stock and a positive impact on the capital-to-labor ratio emerge as statistically significant. Interestingly, the latter result contradicts the one found in the FE model, indicating that countries with increasing capital-to-labor ratio might be substituting capital for immigrant labor from the EaP countries. Finally, negative effects on output per worker are found for immigrants from new EU member states, but the corresponding results for those from EaP countries are insignificant.Footnote 20

6 Conclusions

In this study we contribute to the literature on destination-country consequences of international migration. In particular we look at the effects of immigration from the new EU member states and Eastern Partnership countries on the EU—separately for old EU member states (EU15) and on the EU as a whole (EU27)—between the years 1995 and 2010. Taking into account possible reverse causality from economic indicators to migration flows, our results show positive and significant effects of post-enlargement migration flows from the new EU member states on GDP, GDP per capita, and employment rate and a negative effect on output per worker. Regarding immigration from EaP countries, we find small but statistically significant negative effects on GDP, GDP per capita, employment rate, and capital stock, but a positive significant effect on capital-to-labor ratio, in EU countries.

Our results for intra-EU mobility are in line with the previous literature; complementing it by showing that the generally neutral-to-positive positive effects found at the micro level, or at various levels of aggregation, also show up at the macro, EU-wide, level, and for a number of, but not all, economic indicators. On the other hand, small negative effects are found for immigration from EaP origins. Further research is needed to better understand why EaP immigration differs from mobility from new EU member states. Besides the possibility that this difference emerges due to different composition of immigrant inflows from the two clusters of origins, an alternative hypothesis is that it is an artifact of the different legal status of immigrants from new EU member states and those from EaP countries. One plausible explanation is that free labor mobility contributes to the positive effects of intra-EU migration on the receiving countries by enabling immigrants to allocate and integrate more efficiently. As a corollary, it may well be that legal barriers to immigration from the EaP and their integration hamper positive economic effects of their immigration.

These findings underscore the positive economic effects of intra-EU mobility as a pillar of economic efficiency of the single market in the EU, and provide an economic argument for eliminating, or at least reducing, barriers to labor mobility and immigrant integration. They also highlight the unfortunate gap between what hard data show about labor market impacts of migration, on the one hand and public perceptions and beliefs about free mobility in the EU on the other hand, as also demonstrated by the public debates surrounding Brexit.

Notes

Own calculations based on the data collected and described in the data section below.

All nationals of EU member states as well as their family members enjoy the right of free movement in the EU as stipulated by the Treaty on the European Union, Directive 2004/38/EC, and the Case Law of the European Court of Justice if they do not pose an undue burden for the host member state’s public funds, and they possess comprehensive health insurance.

EU15 refers to the fifteen pre-2004 member states: Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Sweden and United Kingdom. Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Slovakia and Slovenia (referred to as EU10) joined the EU in 2004, Bulgaria and Romania (denoted EU2) joined in 2007, and Croatia was the most recent addition to the EU in 2013. EU8 refers to EU10 minus Cyprus and Malta. EU27 includes EU15, EU10 and EU2.

EaP includes Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine.

In line with the theoretical framework presented in e.g. Borjas (1999), the effect of immigration depends very much on whether the immigrants are substitutes or complements with respect to natives.

The original OECD migration dataset by Pedersen, Pytlikova and Smith (2008) covered 22 OECD destination and 129 source countries during the years 1989–2000 (see Pedersen et al. 2008, for a description of the dataset). For the study by Adserà et al. (2015), we extended the number of destinations to 30 OECD countries and the number of source countries to all world countries, and we extended the time period so that it covers the years 1980–2010. This current dataset covering 42 destinations and years 1980–2010 was used in Cai et al. (2016) and it is thereafter referred as Pytlikova (2011).

Foreign population stock is a number of foreigners from a given country of origin living in a destination in a given year. The foreign population stock data is dated ultimo.

We chose the period from 1995 in order to avoid problems related to different country break-ups, such as countries of Former Yugoslavia and Former USSR.

Ideally, we would like to have comprehensive individual micro datasets that would cover a large universe of destinations, among them also Germany, and a representative sample of immigrants together with population weights (e.g., e.g. European Labour Force Survey data, ELFS) on the other hand, the advantage of using our data is the provision of longer time horizon for the analyses, and a large number of destinations.

However, the numbers for Germany do not include so called “Aussiedlers”, or in other words German resettlers or ethnic Germans, who moved in large numbers from CEECs, in particular from Poland, Czechoslovakia and Romania, to Germany during the nineties. Obviously, if the numbers were included, the share of EU8 and EU2 migrant stocks in Germany would be much higher.

The employment rates are calculated as 1-unemployment rate.

We add interactions of time fixed effects with country group/region fixed effects in order to mitigate any effects of other time-variant variables that might affect the dependent variables. In this way we minimize the potential omitted variable bias. The regional dummies and their interactions with time might also partly account for some underlying trends in economic developments of the regional groups of countries. The region dummies are defined in the following way: Western European country group contains Austria, Belgium, Germany, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, UK and Ireland; Southern European country group contains Italy, France, Spain, Portugal, Greece, Cyprus and Malta; Central and Eastern European country group contains the new EU 2004 and 2007 member countries excluding Malta and Cyprus; Nordic country group covers Denmark, Finland, Norway, Sweden and Iceland.

Stock and Yogo (2005) critical values are derived under the assumption of homoscedasticity and no autocorrelation, and thus their comparison to Kleibergen and Paap (2006) F-statistic that is robust to heteroscedasticity and within-cluster correlation, should be interpreted with caution, as suggested by Baum et al. (2007).

We run similar analyses using immigration to the EU27 countries. It turns out that the results are generally very similar to those estimated for the EU15 countries, except that the coefficients are, as a rule, estimated less precisely. This indicates that the results we observe are primarily driven by the EU15 countries. This is not surprising, given that immigration to the EU15 is considerably larger and has a longer history than migration flows to the rest of the EU. The results are available in Table 5 in Appendix 2.

References

Adserà A, Pytliková M (2015) The role of language in shaping international migration. Econ J 125(586):F49–F81

Angrist JD, Kugler AD (2003) Protective or counter-protective? Labour market institutions and the effects of immigration on EU natives. Econ J 113:F302–F331

Aydemir A, Borjas GJ (2007) Cross-country variation in the impact of international migration: Canada, Mexico, and the United States. J Eur Econ Assoc 5(4):663–708

Balcar J (2014) Soft skills and their wage returns: overview of empirical literature. Rev Econ Perspect 14(1):3–15

Balcar J, Janíčková L, Filipová L (2014) What general competencies are required from the Czech labour force? Prague Econ Pap 23(2):250–265

Bansak C, Simpson NB, Zavodny M (2015) The economics of immigration. Routledge. ISBN 10:0415747066

Barrett A (2010) EU enlargement and Ireland’s labor market. In: Kahanec M, Zimmermann KF (eds) EU labor markets after post-enlargement migration. Springer, Berlin, pp 143–161

Baum CF, Schaffer ME, Stillman S (2007) Enhanced routines for instrumental variables/generalized method of moments estimation and testing. Stata J 7(4):465–506

Bellini E, Ottaviano GIP, Pinelli D, Prarolo G (2013) Geography, institutions and regional economic performance. Springer, Berlin

Benhabib J (1996) On the political economy of immigration. Eur Econ Rev 40:1737–1743

Blanchflower DG, Lawton H (2010) The impact of the recent expansion of the EU on the UK labour market. In: Kahanec M, Zimmermann KF (eds) EU labor markets after post-enlargement migration. Springer, Berlin, pp 181–215

Blanchflower DG, Shadforth C (2009) Fear, unemployment and migration. Econ J 119(535):F136–F182

Blanchflower DG, Saleheen J, Shadforth C (2007) The impact of the recent migration from Eastern Europe on the UK economy, IZA Discussion Paper No. 2615, Bonn: Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA)

Bonin H, Eichhorst W, Florman C, Hansen MO, Skiöld L, Stuhler J, Tatsiramos K, Thomasen H, Zimmermann KF (2008), Geographic mobility in the European union: optimising its economic and social benefits, IZA Research Report No. 19, Bonn: Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA)

Borjas G (1995) The economic benefits from immigration. J Econ Perspect 9(2):3–22

Borjas JG (1999) The economic analysis of immigration. Handb Labor Econ 3(1):1698–1760

Borjas G (2003) The labor demand curve is downward sloping: re-examining the impact of immigration on the labor market. Q J Econ 118:1335–1374

Brenke K, Yuksel M, Zimmermann KF (2010) EU enlargement under continued mobility restrictions: consequences for the german labor market. In: Kahanec M, Zimmermann KF (eds) EU labor markets after post-enlargement migration. Springer, Berlin, pp 111–129

Brücker H, Damelang A (2009) Labour mobility within the EU in the context of enlargement and the functioning of the transitional arrangements: analysis of the scale, direction and structure of labour mobility, background report. IAB, Nürnberg

Cai R, Feng S, Oppenheimer M, Pytlikova M (2016) Climate variability and international migration: the importance of the agricultural linkage. J Environ Econ Manag 79:135–151

Chiswick BR (2011) High-skilled immigration in a global labor market. AEI Press, Washington, DC

D’Amuri F, Ottaviano IPG, Peri G (2010) The labor market impact of immigration in Western Germany in the 1990′s. Eur Econ Rev 52(4):550–570

Docquier F, Özden Ç, Peri G (2013) The labour market effects of immigration and emigration in OECD countries. Econ J R Econ Soc 124(579):1106–1145

Dolado J, Goria A, Ichino A (1994) Immigration, human capital and growth in the host country. J Popul Econ 7(2):193–215

Doyle N, Hughes G, Wadensjö E (2006) Freedom of movement for workers from Central and Eastern Europe—experiences in Ireland and Sweden, SIEPS Report No. 5, Stockholm: Swedish Institute for European Policy Studies

Felbermayr GJ, Hiller S, Sala D (2010) Does immigration boost per capita income? Econ Lett 107(2):177–179

Foged M, Peri G (2016) Immigrants’ effect on native workers: new analysis on longitudinal data. Am Econ J Appl Econ 8(2):1–34

Galgóczi B, Leschke J, Watt A (2009) EU labour migration since enlargement—trends, Impacts and Policies. Ashgate, London

Galgóczi B, Leschke J, Watt A (eds) (2012) EU labour migration in troubled times: skills mismatch, return and policy responses. Ashgate Publishing, Aldershot

Gerdes C, Wadensjö E (2010) Post-enlargement migration and labour market impact in Sweden. In: Zimmermann K, Kahanec M (eds) EU enlargement and the labour market. Springer, Berlin Germany

Gill IS, Raiser M (2012) Golden growth: restoring the lustre of the European economic model. World Bank Publications, Washington, DC

Gilpin N, Henty M, Lemos S, Portes J, Bullen C (2006) The impact of free movement of workers from Central and Eastern Europe on the UK labour market, Working Paper No. 29, London: Department of Work and Pensions

Giulietti C, Guzi M, Kahanec M, Zimmermann KF (2013) Unemployment benefits and immigration: evidence from the EU. Int J Manpow 34(1):24–38

Gonzalez L, Ortega F (2011) How do very open economies adjust to large immigration flows? Evid Span Reg Labour Econ 18(1):57–70

Gormsen C, Pytlikova M (2012) Diasporas and foreign direct investments. In: EALE Annual Conference in Bonn, pp 20–23 Sept 2012

Guzi M, Kahanec M, Mytna Kurekova L (2015) How immigration grease is affected by economic, institutional and policy contexts: evidence from EU labor markets. IZA Discussion Paper 9108. Bonn

Hanson HG (2008) The economic consequences of the international migration of labor. NBER Working Paper No. 14490

Holland D, Fic T, Rincon-Aznar A, Stokes L, Paluchowski P (2011) Labour mobility within the EU. The impact of enlargement and the functioning of the transitional arrangements. Final report, National Institute of Economic and Social Research, London

Hughes G (2007), EU enlargement and labour market effects of migration to Ireland from Southern, Central and Eastern Europe (Paper presented at Second IZA Migration Workshop: EU Enlargement and the Labour Markets, Bonn, 7–8 September 2007). Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA), Bonn

Hunt J, Gauthier-Loiselle M (2010) How much does immigration boost innovation? Am Econ J Macroecon 2(2):31–56

Javorcik BS, Özden Ç, Spatareanu M, Neagu C (2011) Migrant networks and foreign direct investment. J Dev Econ 94(2011):231–241

Kahanec M (2012) Skilled labor flows: lessons from the European union. Discussion Paper 1301, World Bank, Washington

Kahanec M (2013) Labor mobility in an enlarged European union. In: Constant AF, Zimmermann KF (eds) International handbook on the economics of migration. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, pp 137–152

Kahanec M, Zimmermann KF (eds) (2010) EU labor markets after post-enlargement migration. Springer, Berlin

Kahanec M, Zimmermann KF (2014) How skilled immigration may improve economic equality. IZA J Migr 3(1):1–13

Kahanec M, Zimmermann KF (eds) (2016) Labor migration, EU enlargement, and the great recession. Springer, Berlin

Kahanec M, Zaiceva A, Zimmermann KF (2010) Lessons from migration after EU enlargement. In: Kahanec M, Zimmermann KF (eds) EU labor markets after post-enlargement migration. Springer, Berlin, pp 3–45

Kahanec M, Zimmermann KF, Kurekova L, Biavaschi C (2013) Labour migration from EaP countries to the EU—assessment of costs and benefits and proposals for better labour market matching. IZA Research Report No. 56

Kaminska ME, Kahancová M (2011) Emigration and labour shortages: an opportunity for trade unions in the New Member States? Eur J Ind Relat 17(2):189–203

Kato T, Sparber C (2013) Quotas and quality: the effect of H-1B visa restrictions on the pool of prospective undergraduate students from abroad. Rev Econ Stat 95(1):109–126

Kerr SP, Kerr W (2011) Economic impacts of immigration: a survey, NBER Working Paper 16736. Cambridge, MA, NBER

Kleibergen F, Richard P (2006) Generalized reduced rank tests using the singular value decomposition. J Econometrics 133(1):97–126

Kureková L (2011) From job search to skill search. Political economy of labor migration in Central and Eastern Europe, Ph.D. dissertation, Budapest: Central European University (CEU)

Lemos S, Portes J (2008) The impact of migration from the new European union member states on native workers, Working Paper No. 52, Leeds: Department for Work and Pensions

Longhi S, Nijkamp P, Poot J (2010) Joint impacts of immigration on wages and employment: review and meta-analysis. J Geogr Syst 12(4):355–387

Manacorda M, Manning A, Wadsworth J (2012) The impact of immigration on the structure of wages: theory and evidence from Britain. J Eur Econ Assoc 10(1):120–151

Nathan M (2011) The long term impacts of migration in British cities: diversity, wages, employment and prices. Spatial Economics Research Center, Discussion Paper no 67

Nathan M (2014) The wider economic impacts of high-skilled migrants: a survey of literature for receivivng countries. IZA J Migr 3:4

Ortega F, Peri G (2009) The causes and effects of international migrations: evidence from OECD countries 1980–2005 (No. w14833). National Bureau of Economic Research

Ottaviano GI, Peri G (2008) Immigration and national wages: clarifying the theory and the empirics (No. w14188). National Bureau of Economic Research

Ottaviano GI, Peri G (2012) Rethinking the effect of immigration on wages. J Eur Econ Assoc 10(1):152–197

Palmer J, Pytliková M (2015) Labor market laws and intra-european migration: the role of the state in shaping destination choices. Eur J Popul 31(2):127–153

Parrotta P, Pozzoli D, Pytlikova M (2014a) The nexus between labor diversity and firm’s innovation. J Popul Econ 27(2):303–364

Parrotta P, Pozzoli D, Pytlikova M (2014b) Does labour diversity affect firm productivity? Eur Econ Rev 66:144–179

Pedersen JP, Pytlikova M, Smith N (2008) Selection and network effects—Migration flows into OECD countries 1990–2000. Eur Econ Rev 52(1):1160–1186

Peri G (2006) Immigrants, skills and wages: reassessing the economic gains from immigration. IPC IN FOCUS, the American Immigration Law Foundation’s Immigration Policy Center, Washington, DC, vol 5, no 3

Peri G (2007) America’s stake in immigration: Why almost everybody wins.Milken Institute Review, 3rd Quarter, pp 40–49

Peri G (2008) Immigration accounting: US states 1960–2006. CReAM discussion paper No. 05

Peri G (2012) The effect of immigration on productivity: evidence from US states. Rev Econ Stat 94(1):348–358

Peri G (2016) Immigrants, productivity, and labor markets. J Econ Perspect 30(4):3–30

Peri G, Requena F (2010) The trade creation effect of immigrants: testing the theory on the remarkable case of Spain. Can J Econ 43(4):1433–1459

Peri G, Sparber C (2009) Task specialization, immigration and wages. Am Econ J Appl Econ 1(3):135–169

Peri G, Shih K, Sparber C (2015) STEM Workers, H-1B visas, and productivity in US cities. J Labor Econ 33(S1):S225–S255

Pytlikova M (2011) International migration dataset. Mimeo, Aarhus

Schreyer P, Bignon P-El, Dupont J (2003) OECD capital services estimates: methodology and a first set of results. OECD Statistics Working Papers, vol 06, no 1

Stock JH, Yogo M (2005) Testing for weak instruments in linear IV regression. In: Andrews DWK, Stock JH (eds) Identification and inference for econometric models. Cambridge University Press, New York, pp 80–108

Wadsworth J (2014) Immigration, the European Union and the UK labour market. CEP Policy Analysis, CEPPA015. The London School of Economics and Political Science, Center of Economic Performance, London, UK

Acknowledgements

The financial support in relation to the project on “Costs and Benefits of Labour Mobility between the EU and the Eastern Partnership Partner Countries” funded by the European Commission (EuropeAid/130215/C/SER/Multi) is gratefully acknowledged. Kahanec thankfully acknowledges the financial support of EDUWORKS Marie-Curie ITN network, funded by the 7th Framework Program of the European Union (No. 608311). Pytlikova’s research was supported in part by the Operational Programme Education for Competitiveness (No. CZ.1.07/2.3.00/20.0296) and by a Czech Science Foundation grant (No. GA15-24642S). Ioana Neamtu provided excellent research assistance. The usual disclaimer applies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Data

See Table 4.

Appendix 2: Impacts of foreign population in the EU27

See Table 5.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Kahanec, M., Pytliková, M. The economic impact of east–west migration on the European Union. Empirica 44, 407–434 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10663-017-9370-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10663-017-9370-x

Keywords

- EU enlargement

- Free mobility of workers

- Migration impacts

- European single market

- East–west migration

- Eastern partnership