Abstract

This paper empirically investigates the relationship between long-run economic growth and output volatility for the time series experience of 25 OECD countries between the years 1960 and 2013. Given the low number of observations, we reject, based on Monte Carlo simulations, the obvious choice of Garch estimation, and instead propose a pooled OLS estimator between a filtered GDP series that eliminates the cyclicality and the fluctuations around this trend. We find strong empirical evidence for a positive relationship between output variability and economic growth. This relationship seems to confirm theoretical literature which proposes such a positive relation.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

For a long time, the field of macroeconomics has between firmly divided between the analysis of the business cycle and the investigation of long-run determinants of economic growth. This distinction, however, is rather arbitrary and has been challenged by recent theoretical models and by empirical evidence that points to long-run performance being explained in part by business-cycle behavior and output variability. The aim of this paper is to empirically investigate the relationship between economic growth and output volatility.

The earliest theoretical argument for a relation between economic growth and the business cycle dates back to Schumpeter (1939), who argued that recessions provide a cleansing mechanism for the economy, where old technologies get replaced by newer technologies, and will be better adapt to economic growth thereafter. In a similar spirit Black (1981) argues that the average severity of a society’s business cycle is largely a matter of choice. His idea was that economies face a positive risk-return trade-off in their choice of technology, as economic agents would choose to invest in riskier technologies only if the latter were expected to yield a higher return and hence, greater economic growth.

A series of papers have subsequently focused on the relationship between volatility and growth in exogenous growth models. On the one hand, the focus was on the impact of volatility on uncertainty, precautionary savings and hence accumulation of capital (cf. Boulding 1966; Leland 1968; Sandmo 1970). On the other hand, Bernanke (1983) and Pindyck (1991) argue that if there are irreversibilities in investment, then increased volatility will lead to lower investment and hence lower capital accumulation.

More recently, within an endogenous growth model, Aghion and Saint-Paul (1998) show that the sign of the relation depends on whether the activity that generates growth in productivity is a complement or a substitute to production. In the case where they are substitutes, since the opportunity cost of productivity-improving activities such as reorganizations or training falls in recessions, larger variability leads to higher long-term growth. This idea has recently been formalized in an endogenous growth framework by Jovanovich (2006). He claims that the choice of a growth rate leads to a positively correlated stochastic cost, generating volatility.

A number of empirical studies on the relationship between growth and volatility have been conducted. Campbell and Mankiw (1987) were among the first to report permanent effects on the level of GDP from shocks to output growth, first for the US and later on for a selected sample of various countries (Campbell and Mankiw 1989). Hall (1988) and Burnside et al. (1993) show that the Solow residual is correlated to economic variables, and can therefore not be purely exogenous, as suggested by the real business cycle literature, suggesting that trend and fluctuation of output should be investigated jointly. Whilst it provides a confirmative test for models of exogenous growth and volatility, these studies fail to provide a test for models of endogenous growth and volatility.

The first empirical study that can be applied to endogenous growth models was done by Zarnowitz (1981). He identified periods of relatively high and relatively low economic stability by reviewing annual real GDP growth rates in the US between 1882 to 1980 and accounts found in the literature on economic trends and fluctuations. He then calculated the yearly growth rate and the variance of the periods with high economic stability (group A) and low economic stability (group B). Though the mean growth rate of group A was higher, he could not reject the null hypothesis that the difference between the mean growth rates for groups A and B was due to chance.

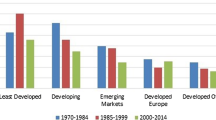

The first econometric study investigating the link between growth, output variability—as measured by the standard deviation of the growth rate—and further macroeconomic variables was conducted by Kormendi and Mequire (1985). By averaging each country’s time series experience into a single data point and estimating a cross-section of forty-seven observations, they found that higher output variability leads to higher economic growth. Grier and Tullock (1989), who used a pooled structure (five-year averaging) to account for both between- and within-country effects, confirmed Kormendi and Meguire’s results.

The paper closest to this is by Mills (2000). He applied various filters that are explicitly designed to capture movements in a time series that correspond to business-cycle fluctuations in twenty-two countries. Subsequently, he calculated the standard deviation of the output (filtered) series and visualized the bivariate relationship between growth and volatility by superimposing robust nonparametric curves on scatter plots. He found a positive relationship. In contrast to our paper, Mills (2000) suppresses all fluctuations of output at frequencies higher than his filter.

When analyzing the relationship between economic growth and output fluctuations, we are essentially investigating the first moment of the time series in first differences, and its corresponding second moment, i.e. the variance of the differentiated time series. There exists a standard econometric tool to analyze this relationship, the generalized auto-regressive conditional heteroscedacity (GARCH) class of models. And indeed, several authors have employed this methodology to analyze the relationship of output and volatility.

Ramey and Ramey (1995), using a panel structure, measured volatility as the standard deviation of the residuals in a growth regression consisting of the set of variables identified by Levine and Renelt (1992) as the important control variables for cross-country growth regressions. Ramey and Ramey (1995) use the estimated variance of the residuals in their regression, under the assumption that it differs across countries, but not time. In such, it can be considered an early predecessor of GARCH models. They find a negative relation between long-run growth and volatility. By contrast, Caporale and McKiernan (1998) and Grier and Perry (2000) examined the issue from a pure time series perspective. Caporale and McKiernan (1998) ran an ARMA(1,2)-GARCH(0,1)-M model and Grier and Perry (2000) ran a complex bivariate GARCH(1,1)-M model for US GDP growth. The former found a significant positive relationship while the latter found an insignificant positive relationship between growth and volatility.

The fact that these studies yield opposite results may come as a surprise. However, GARCH models were invented for financial time series, with a large number of observation. In Monte-Carlo simulations, we demonstrate in "Appendix 1" that the widely-used and highly-sophisticated GARCH-in-mean models are inappropriate for this purpose as they require the estimation of too many parameters for the short time series that normally confront macroeconomists. Using an interantional panel with quarterly data, and thus a sufficient number of observations, Trypsteen (2013) recently showed in a Garch-M model a positive relation between growth and volatility, if cross-country interactions of shocks are factored in. On the downside, quarterly data are less precise and prone to seasonal fluctuations.

Imb (2007) studies the relationship between economic growth and business cycles at a sectoral level using GARCH methods. In a panel of 47 countries, 28 sectors, and a period from 1970 to 1992, he finds a positive relationsship between growth and volatility, in contrast to the findings of Ramey and Ramey (1995).

This leaves us with the more conventional approach of separating the annual time series into a trend and a cyclical component, and then investigate their relationship. There is a large number of filters available, most of them developed by the finance literature. We have decided to adopt the HP-filter. Our measure of volatility is superior to any other measure of volatility we investigated due to its stability with respect to small changes in the data.

This paper continues as follows. After this introdcution, we present the data and the methodology in Sect. 2. The empirical analysis presented in Sect. 3 is based on the growth experience of 25 OECD countries between 1960 and 2013. After calculating the trend growth rate for each country using the HP-filter, we divided the data for each country into several non-overlapping sub-samples. For each sub-sample, the average growth rate and the volatility—based on the squared deviations of the actual growth rate from the trend growth rate—was computed. This not only mitigated the effect of assuming constant volatility and constant growth rates, the technique also accounted for the within-country variation of the volatility in our subsequent regression analysis. We conclude that there is a significant positive relationship between output variability and growth. This relationship is robust against outliers and does not hinge on the sub-sample period chosen.

2 Data and methodology

We use time series for all 25 countries in the AMECO databaseFootnote 1 that provide continous annual series for gross domestic product at constant market prices per capita from 1960 to 2013. These countries are Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Germany, United Kingdom, Greece, Finland, France, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Luxembourg, Mexico, Netherlands, Norway, New Zealand, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, and the USA).Footnote 2

In order to analyze the relationship between economic growth and volatility, we will ask whether a measure of volatility is correlated with changes in output growth, by running a linear regression of the type,

where \(\alpha \) and \(\beta \) are parameters, and \(\sigma _t\) measures the standard deviation of the time series.Footnote 3 \(u_t\) is an error term. For a given time series, one could estimate the above Eq. (1), then use the estimator for the variance \(\sigma ^2\) and reestimate the above equation until it converges.Footnote 4

This is essentially what GARCH models do. However, estimating a time-varying variance requires a time series for longer than the one available to us here. In "Appendix 1", using Monte-Carlo simulations, we show that under reasonable parameter configurations, the variance of the estimator from its true value is unacceptably large.Footnote 5 We therefore have to resort to the next best option, using band-pass filters. An ideal band-pass filter is a linear transformation of \(g_t\) that isolates the components that lie within a particular band of frequencies. Applied to GDP growth rates, the filter eliminates very slow-moving (’trend’) components from slow moving components that correspond to business-cycle fluctuations. The (square) difference between the actual and the filtered series could then serve as a measure of volatility. Leser (1961) proposed a filter that is similar to the band-pass filter and has been widely used in business-cycle research, where it is known as the Hodrick-Prescott (henceforth HP) filter. The HP-filter not only exhibits the advantage of being well known in economics, it is also the only filter separating the series into only two components. All other decompositions split the sample into at least three components, and we would therefore have to ignore the higher frequencies from our analysis. The Hodrick-Prescott filtered growth rate \(\mu _t\) is obtained by solving

where \(L^n\mu _t =\mu _{t-n}\). The objective was to set the smoothing parameter \(\lambda \) such that the filtered series would be a straight line. Visual inspection (see Figs. 3, 4 in "Appendix 1" suggested setting the smoothing parameter, \(\lambda \), to 6400. Whilst business cycle models use 1600 to elimiate seasonal trends, we use \(4 * 1600 = 6400\) to smooth over an average business cycle of four years.

We use both the full length of the series (1960–2013) and split the sample once or twice to gain additional observations without much loss of generality. We estimate the cross section (1 period) with OLS, and estimate the two and three period splits in a pooled regression. In order to avoid end-point problems typically associated with the HP filter, we also present results where we eliminate a few observations at beginning and at the end of the period. Finally, we also cut the series in 2005 to eliminate the financial crisis from our sample. For each sample split, we calculate the average annual growth rate as the geometric average of the annual growth rate of the HP filtered series,

We can then define the variance of the time series as the difference between actual GDP and its HP filtered series,

The following table gives the summary statistics for both variables for the different sample splits (Table 1).

3 Results

As mentioned above, we use both the full length of the series (1960–2013) and split the sample once or twice to gain additional observations. Table 2 below presents these results.

In all three scenarios, we obtain a positive and significant correlation between output volatility and output growth. In the third and fourth column of Table 2 we can observe a positive and significant coefficient of 0.36. To give an economic size of the effect, we find that an increase in volatility by one standard deviation (0.0075) would increase the annual GDP growth rate by 0.27 percentage points (\(0.0075 \times 0.36 = 0.0027\)). This essentially implies that their is a trade-off between high growth and high volatility and low growth and low volatility.Footnote 6

Only if we limit ourselves to the full sample period, thus essentially running a cross section analysis, can we not reject the null hypothesis of no correlation at the 5 % significance level. The reason may be the non-stationarity of the time series (real per capita GDP growth rates) over the longest sample period (1960–2013). In order to verify this hypothesis, we have run three different tests for non-stationarity, the augmented Dickey–Fuller test, and the Kwiatkowski–Phillips–Schmidt–Shin (KPSS) tests, with and without the inclusion of a time trend. We present the results of this test in "Appendix 3". Out of our sample of 21 countries, all three tests point to stationarity of the data for only five countries, confirming our hypothesis.

In order to account for the sensitivity of HP filters with respect to endpoints, we run the same exercise, but eliminate the first and last three observations. The findings, presented in Table 3, support our previous results.

The effect of shortening the sample, if anything, has gotten slightly stronger and still remains statistically significant. Once again, the effect is smallest and significant only at the 10 % level for the pure cross section analysis.

All results above, however, include the financial crisis, which was certainlyFootnote 7 an excemptional event. In order to be sure that we do not pick up effects generated by the financial crisis starting in 2007, we will present below two estimations that end before the financial crisis started. Table 4 cuts the sample by 6 years on both sides.

If anything, the inclusion of the financial crisis, prone to high volatility and low growth rates, worked against our results. Here the estimated correlation between volatility and economic growth shows up to be close to 0.5. Note that in this case the significance on the pure cross section completely vanishes. The inclusion or exclusion of a few years can thus completely alter the results in a pure cross section, which may be considered as a further hint about the limits of Ramey and Ramey (1995).

We then estimate a sample that starts in 1960 but ends in 2005, thus well before the financial crisis (and its preceding bubble) started. The results are presented in Table 5.

Again, our main result, that there is a positive relation between economic growth and the volatility of output, holds. The coefficient returns to 0.3 and is significant at the 5 % level, again with the exception of the pure cross section analysis.

Conventional growth regression tend to include a series of control variables, such as the initial level of GDP, or human and physical capital. We present results for the initial level of GDP in the estimation, which does little to the results. Unsurprisingly, with a dataset of rather homogenous industrialized countries, correcting for conditional convergence (which is the reason for the inclusion of initial GDP) proves insignificant (Table 6).

Finally, volatility may be positively related to the average, if variations are proportional (same percentage change).Footnote 8 Although average GDP growth rates do not differ much across our sample (as can be verified from Table 1), we use the coefficient of variation as an alternative explanatory variable in our model. Obviously, coefficients change, but the general message of the paper remains untouched, higher volatility is correlated with higher rates of economic growth in the industrialized countries.

4 Conclusions

This paper provides empirical results of a robust and positive relationship between economic growth and volatility in industrialized countries. These results should be treated with care, in particular with respect to generalizations to other economic realities. We use the well-known Hodrick-Prescott filter to separate GDP time series into a trend component and a cyclical component, and then use period averages to obtain statistics for growth and volatility. This method is preferential to other band-pass filtering techniques, but also with respect to GARCH methods, which are unfit for short time series such as annual national accounting data. Using the time series experience of 25 OECD countries between 1960 and 2013, we have presented strong empirical evidence for a positive relationship between output variability and economic growth (Table 7).

This paper presented events for a positive correlation between economic growth and volatility. It does not, however give any indication on a causal relationsship between these two variables. If faster economic growth cannot be achieved gradually, but comes only in (boom-bust) waves, than faster growth would inevitably lead to higher volatility. By contrast, if we think of the economic system in an evolutionary perspective, than a higher volatility would give rise to more permutations of the economic system, and may discover fast growing variants more likely. In this case, higher volatility would lead to faster economic growth. Finally, there may be a third variable, such as innovation, that drives both volatility and growth. If a new innovation, which will boost economic growth, also disrupts the current business models, it may lead to creative destruction, and a higher rate of innovation would lead to both faster growth and higher volatility. Further research on the causal relationship is suggested.

This is particularly important, as the positive relationship postulated in this paper has important implications. An increase in economic growth comes at the price of higher volatility, or vice versa, depending on the direction of causality. Policy measures to boost economic growth may lead to higher volatility, generating welfare losses in terms of high unemployment and firm closures. Policy measures to stabilize the economy may come at a price of lower rates of economic growth, thus harming in particular future generations, who would benefit from a bigger economy. The positive relationship between growth and volatility implies that there is no first best policy strategy (boost growth and stabilty follows or stabilize the economy and it will grow), but instead a tradeoff, where the benefits of higher stability to current generations has to be weighted against the loss to for future generations due to a decline in economic growth.

Notes

ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/db_indicators/ameco.

We refrain from considering a wider range of countries for a fear of data quality. Whilst the Penn World Tables are certainly good to look at differences in economic growth between countries, we have serious concerns about their quality when looking at volatility. Indeed, a recent study by Cuaresma et al. (2016) shows in part dramatic differences in GDP between different waves of PWTs. This implies that much volatility is due to the poor quality of the data collection, and not actual underlying economic fundamentals. An illustrative example is the 89 % GDP increase of Nigeria due to a rebasing of the national telecom industry. Statistics for industrialized countries are more reliable, so we prefer to limit the sample.

We refrain from including control variables in our estimation, except for initial GDP in Table 6. Unless control variables would be correlated with the variance measure adopted, the estimator for \(\beta \) remains unbiased. Most control variables that we can think of, such as policy variables, would work in our favor, reducing the explanatory power of volatility on economic growth.

It should also be noted that whenever one has an unbiased estimator for \(\sigma ^2\), the square root of \(\hat{\sigma }^2\) is a biased— depending on the shape of the distribution and the sample size—estimator of \(\sigma \) due to Jensen’s inequality, \(\mathbb{E}\left[ \hat{\sigma }\right] = \mathbb {E}\left[ \sqrt{\hat{\sigma }^2}\right] < \sqrt{\mathbb {E}\left[ \hat{\sigma }^2\right] }= \sqrt{\sigma ^2}= \sigma \).

This may be the reason why papers based on this methodology yield contrasting results.

You can’t have the pie and eat it, too.

hopefully :-)

I am grateful to a referee for pointing this out.

The intercepts were set to \(\omega = 0.0001\) and \(\kappa = 0.005\), respectively and \(\epsilon \sim \mathcal {N}(0,1)\)

The elasticity measures the percent change in m(x) for a 1 percent change in x. \(m(x)_\epsilon = \frac{m'(x)x}{m(x)} = \frac{d \ln m(x)}{d \ln x}\)

The leverage assesses how far away a value of the explanatory variable is from the mean value: the farther away the observation the more leverage it has. \(h_{ii}\) is the ith diagonal element of \(X(X'X)^{-1}X'\). In the bivariate case \(h_{ii} = \frac{1}{n}+\frac{\left( x_i - \bar{x}\right) ^2}{\left( n-1\right) s^2_x}\).

The studentized residual is \(r_i = \frac{e_i}{s_e\sqrt{1-h_{ii}}}\).

References

Aghion P, Saint-Paul G (1998) Uncovering some causal relationships between productivity growth and the structure of economic fluctuations: a tentative survey. Labour 12(2):279–303

Bernanke B (1983) Irreversibility, uncertainty, and cyclical investment. Q J Econ 98(1):85–106

Birkes D, Dodge Y (1993) Alternative methods of regression. Wiley, New York

Black F (1981) The abcs of business cycles. Financ Anal J 37(6):75–80

Boulding KE (1966) Economic analysis, volume I: microeconomics, 4th edn. Harper & Row, New York

Burnside C, Eichenbaum M, Rebelo S (1993) Labor hoarding and the business cycle. J Polit Econ 101(2):245–273

Campbell J, Mankiw NG (1987) Are output fluctuations persistent? Q J Econ 102(4):857–880

Campbell J, Mankiw NG (1989) International evidence on the persistence of economic fluctuations. J Monet Econ 23(2):319–333

Caporale T, McKiernan B (1998) The fischer black hypothesis: some time-series evidence. South Econ J 64(3):765–771

Cuaresma JC, Feldkircher M, Grün B, Hofmarcher P, Humer S (2016) Measuring income with penn world table data: Reaching consensus? Mimeo

Grier KB, Perry MJ (2000) The effects of real and nominal uncertainty on inflation and output growth: some garch-m evidence. J Appl Econom 15(1):45–58

Grier K, Tullock G (1989) An empirical analysis of cross-national economic growth, 1951–1980. J Monet Econom 24(2):259–276

Hall R (1988) The relation between price and marginal cost in US industry. J Polit Econ 96:921–947

Hawkins D (1980) Identification of outliers. Chapman and Hall, London

Huber P (1964) Robust estimation of a location parameter. Ann Math Stat 35:73–101

Imb J (2007) Growth and volatility. J Monet Econ 54(7):1848–1862

Jovanovich B (2006) Asymmetric cycles. Rev Econ Stud 73(1):145–162

Kormendi R, Mequire P (1985) Macroeconomic determinants of growth: cross-country evidence. J Monet Econom 16(2):1345–1370

Leland HE (1968) Saving and uncertainty: the precautionary demand for saving. Q J Econ 82(3):465–473

Leser C (1961) A simple method of trend construction. J R Stat Soc Ser B (Methodological) 23:91–107

Levine R, Renelt D (1992) A sensitivity analysis of cross-country growth regressions. Am Econ Rev 82(4):942–963

Mills T (2000) Business cycle volatility and economic growth: a reassessment. J Post-Keynes Econ 23:107–116

Nelson D (1990) Stationarity and persistence in the garch(1,1) model. Econom Theory 6(3):318–334

Pindyck RS (1991) Irreversibility, uncertainty, and investment. J Econ Lit 29(3):1110–1148

Ramey G, Ramey VA (1995) Cross-country evidence on the link between volatility and growth. Am Econ Rev 85(5):1138–1151

Sandmo A (1970) The effect of uncertainty on saving decisions. Rev Econ Stud 37(3):353–360

Schumpeter JA (1939) Business cycles, 1st edn. McGraw-Hill, New York

Trypsteen S (2013) ‘Cross-country interactions, the great moderation and the role of volatility in economic activity’. University of Nottingham, Nottingham

Tsay R (2005) Analysis of financial time series, 2nd edn. Wiley, Hoboken

Wainer H (1976) Robust statistics: a survey and some prescriptions. J Educ Stat 1(4):285–312

Zarnowitz V (1981) Business cycles and growth: some reflections and measures. Passau, pp 475–508

Acknowledgments

Open access funding provided by Vienna University of Economics and Business (WU). The author would like to thank Michael Stastny and Cristiana Zanzottera for colaboration on previous drafts and the particpants of the CGBCR conference in Manchester, in particular Vahagn Jerbashian and Steven Trypsteen, for helpful comments and suggestions. Financial support from OeNB Jubiläumsfonds Projekt Nr. 13991 is gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1: Garch-in-mean regression models

In the GARCH-in-Mean (GARCH-M) model the conditional variance of the error term is used as an explanatory variable in the Eq. (1) for the conditional mean of the variable to be explained. The error term follows a GARCH(p,q) model

where \(\epsilon _t \sim IID(0,1)\) and \(\sigma _t^2\), the conditional variance of \(u_t\) conditional on all the information up to time \(t-1\), \(\mathcal {F}_{t-1}\), is given as:

All coefficients in Eq. 6 are necessarily non-negative. Nelson (1990) showed that a GARCH(1,1) process is strictly stationary when \(\mathbb {E}[\text{ log }(\alpha \epsilon ^2_t + \beta )] < 0\). When \(\epsilon _t \sim N(0,1)\), the condition for strict stationarity is weaker then the condition for covariance stationarity \(\alpha + \beta < 1\).

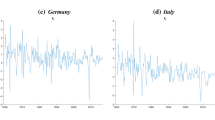

Figure 1 shows a trajectory of a GARCH(1,1)-M process. The risk premium parameter was set to 2, a value in between those obtained by the GARCH(0,1)-M model of Caporale et al. (0.7) and the bivariate GARCH(1,1)-M model Grier et al. (3.5). The parameters for the variance equation, \(\alpha _j\) and \(\beta _j\), were set to 0.1 and 0.8, respectively. These values are common in finance (see for instance Tsay 2005) and close to the ones obtained by Grier and Perry (2000) (0.2 and 0.7).Footnote 9 Though it seems that such processes are capable of producing series that resemble actual GDP growth rates, unfortunately, very long time series (n >> 2500) are required for estimating such processes efficiently.

In a small Monte-Carlo simulation running 100 realizations of a GARCH(1,1)-M process with \(t = 1,\ldots ,200\) and with the parameters as given above and re-estimating the process yielded the distribution of the GARCH-in-Mean effect as shown in Fig. 2.

The average is close to the true mean of our simulation, but the standard deviation of 15 is unacceptably large. In 25 percent of our simulation we obtained an estimate that was at least twice as large but had the opposite sign. Apart from this technical obstacle, the implication of the fact that the measure for volatility is based solely on forecast uncertainty seems to be not fully understood when the mean Eq. 1 contains additional regressors.

Appendix 2: Real per capita GDP growth and HP filtered

Appendix 3: Stationarity

The following table shows the results for the ADF test and the two KPSS tests for each country. Black squares denote evidence for non-stationarity (ADF: nonrejection of the null hypothesis, KPSS: rejection of the null hypothesis) while white squares denote evidence for stationarity. Out of our sample of 21 countries, all three tests point to stationarity of the data for only five countries, confirming our hypothesis.

Appendix 4: Robustness analysis

1.1 Appendix 4. 1: Variants of ordinary least squares

Regression analysis is concerned with the question of how y can be explained by x. This means a relation of the form

where m is a function in the mathematical sense. It determines how the average value of y changes as x changes. In a parametric approach, the obvious choice is linear, as discussed in Sect. 2, and functions whose parameters can be estimated by ordinary least squares after applying a linearizing transformation on the variables, like

In Eq. 8, \(\beta \) measures the elasticityFootnote 10 of m(x) with respect to x. It can be written as \(\ln m(x) = \ln \alpha + \beta \ln x\). In Eq. 9 \(\beta \) gives the proportionate change in m(x) per unit change in x. Vice versa for Eq. 10. Finally, we try to use the variance instead of the standard deviation,

Table 9 summarizes the estimation results. In the log-linear version the estimate for \(\beta \) is significantly different from zero (p value \(< 0.001\)). The log–log model (8, dashed line) and the lin-log model (9, dot-dashed line) still exhibit coefficient that are significant at the 5 % significance level.

The coefficients cannot be compared directly, so Fig. 5 draws the regression lines for all four models, showing that they are all very similar in the relevant area, so that we can confirm the result of the Sect. 3.

1.2 Appendix 4.2: Robust regression: M-estimation

A statistical procedure is regarded as ’robust’ if it performs reasonably well even when the assumptions of the statistical model are not true. M-regression, the most common general method of robust regression introduced by Huber (1964), was specifically developed to be robust with respect to the assumption of normality (see Birkes and Dodge 1993). Consider our linear model

for the ith of n observations. The fitted model is

The general M-estimator minimizes the objective function

where the function \(\rho \) gives the contribution of each residual to the objective function. Obviously, for least-squares estimation, \(\rho \left( e_i\right) = e_i^2\). The Huber M-estimator uses a function \(\rho \) that is a compromise between \(e^2\) and \(|e|\):

Tukey’s biweight estimator is defined as:

The value k for the Huber-M and Tukey’s biweight estimator is called a tuning constant; smaller values of k produce more resistance to outliers, but at the expense of lower efficiency when the errors are normally distributed. We choose the pre-selected values of \(k = 1.345\sigma \) for Huber’s and \(k = 4.685\sigma \) for Tukey’s estimator (where \(\sigma \) is the standard deviation of the errors).

Figure 6 shows the regression lines for the OLS (solid), Huber (dashed), and Tukey (chain) estimates. Both the Huber and the Tukey estimates of the slope are slightly lower than the OLS estimate, 0.45 and 0.4, respectively, but still significantly different from zero. We can therefore still confirm the robustness of the OLS estimator presented in the previous chapter.

1.3 Appendix 4.3: Detection of influential data points

The purpose of any sample is to represent a certain population, actual or hypothetical. Influential data points or outliersFootnote 11 in a sample are likely to influence the sample-based estimates of the regression coefficients. There are many sources of outliers such as sampling a member not of that population, bad recording or measurement, errors in data entry, etc. For whatever reason they have come to exist, outliers will lessen the ability of the sample statistics to represent the population of interest. A common method of dealing with apparent outliers in a regression situation is to remove the outliers and then refit the regression line to the remaining points.

Since no data points that obviously qualify as an outlier could be found by visual inspection, we calculated Cook’s distance for each observation. The 100(\(1-\alpha \)) % joint confidence region for the parameter vector \(\beta \) is

Cook’s Distance is defined as

The 100(\(1-\alpha \)) % joint ellipsoidal confidence region for \(\beta \) given in 15 is centered at \(\hat{\beta }\). The quantity \(C_i\) measures the change in the center of this ellipsoid when the ith observation is omitted, and thereby assesses its influence. \(C_i\) is the scaled distance between \(\hat{\beta }\) and \(\hat{\beta }_{-i}\). An alternate form of Cook’s distance is

where \(h_{ii}\) is the leverageFootnote 12 and \(r_i\) the studentized residualFootnote 13 \(C_i\)s that are above the threshold value of the 50th percentile of the F distribution with k and N-k degrees of freedom (in our case 0.7) are regarded as influential observations. According to this definition, as can be seen in Fig. 7, our sample does not contain any influential observations.

The most influential data points in our sample are Greece\(_{1960-74}\) (#4) with a growth rate of 6.2 % and a standard deviation of 4.7 %, Turkey\(_{1990-2005}\) (#42) with a growth rate of 2.4 % and a standard deviation of 5.4 %, and Japan\(_{1960-74}\) (#46) with a growth rate of 7 % and a standard deviation of 3.2 %. Running an OLS regression without those three data points yielded a slope of 0.46, wich is similar to the results obtained in Sect. 3. Once again, this confirms our results of a positive and significant relationship between economic growth and volatility.

1.4 Appendix 4.4: Nonparametric estimation—kernel regression

Our final test of robustness is to use nonparametric estimation methods. The nonparametric approach does not assume any functional form for m(x), but rather goes back to the statistical definition of conditional expectation:

Plugging in Kernel estimates for the marginal density, \(f_X\left( x\right) \), and the joint density, \(f_{Y,X}\left( y,x\right) \), delivers an estimate m(x) of the conditional expectation at point x:

This has become known as the Nadaraya–Watson estimator. Figure 8 shows two Nadaraya–Watson regression estimates, one with high bandwidth (dashed line) and one with low bandwidth (chained line). In the dense region, i.e. in the region where many data points are available, the estimates tell the same story as the OLS regression line, so it seems that there really is a linear relationship between volatility and growth. The Nadaraya–Watson estimates become very erratic in the region where the standard deviation is larger than 3.5 %. This was to be expected, since only eight data points fall into this region.

After running an entire series of robustness tests, from altering the sample, running non-linear versions of OLS regressions, M-estimations, checking against critical data points, and nonparametric methods, which all point toward a positive and significant relationship between economic growth and volatility, we are convinced about the robustness of our results indicated in Sect. 3.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Zagler, M. Empirical evidence on growth and business cycles. Empirica 44, 547–566 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10663-016-9336-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10663-016-9336-4