Abstract

In the study we investigate the effectiveness of the National Bank of Poland in counteracting the negative results of the financial crisis in the Polish interbank market. The situation was exceptional in a sense, that during the period of the financial crisis the Polish interbank market experienced liquidity surplus, and the main problem of the central bank was to regain confidence among commercial banks and stimulate interbank transactions. We concentrate on the spread between the rate of overnight interbank loans and the reference rate and based upon its dynamics we assess the monetary policy of the Polish central bank. Using econometric techniques we study how the central bank influenced the spread, when its control over it weakened and when was it strengthened. The study is supported by the results of the survey directed to the headquarters of commercial banks. We conclude that the ability of the central bank to control overnight rate was temporarily lost during the first phases of the financial crisis, but gradually regained after implementation of the confidence pact.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The aim of the research was to assess the ability of the Polish central bank to control the rate of overnight loans in the Polish interbank market and conduct its monetary policy during the confidence crisis, as well as facing the liquidity surplus. The Polish interbank market is special in a sense that liquidity surplus has been present there even since 1994 (National Bank of Poland 2009). However, together with the outbreak of the financial crisis, the confidence in the Polish interbank market declined drastically. Commercial banks preferred to accumulate liquidity surplus and performed almost no interbank transactions of maturity longer than 7 days. Banks preferred to keep their surplus on their current accounts with the central bank or in the form of deposit facility, and they significantly limited participation in the 7-day open market operations conducted by the National Bank of Poland (NBP) (National Bank of Poland 2009). The latter resulted in the so called underbidding (i.e. the situation during the tenders for the NBP bills, when the banks’ total bid is lower than the supply offered by the central bank). As a consequence, the effectiveness of the central bank in stabilization of the market rates, what is one of the main goals of the monetary policy, diminished significantly.

Our goal was to assess the effectiveness of the monetary policy of the Polish central bank, using econometric methods, as well as with respect to the results of the survey, sent to the head-quarters of the Polish commercial banks. The problem of assessing the effectiveness of the stabilization policy of central banks using econometric methods is also rather new in literature. Panigirtzoglou et al. (2000) studied the effectiveness of controlling the interbank rates through the key interest rates of the central banks of Great Britain, Italy and Germany using ARMA–GARCH models. Vila Wetherilt (2003) studied the impact of the changes of the main refinancing operation rates of the Bank of England on the market interest rates. Nautz and Offermanns (2007) and Hassler and Nautz (2008) analyzed the effectiveness of the European Central Bank investigating long memory of the spread between EONIA and the MRO rate. There are also papers in which the authors investigate the impact of particular factors on the spread, among others: demand–supply ratio of central bank bills, balance of the overnight deposit and credit in central bank, dummies indicating end of the period during which commercial banks are obliged to maintain their required reserve level—see egg. Moschitz (2004), Ejerskov et al. (2003), Wuertz (2003), Linzert and Schmidt (2008), Abbassi and Nautz (2010).

Beirne (2011) and Beirne et al. (2010) show that during the subprime crisis the European Central Bank lost some of its control over the overnight interest rate. The analogous research for the Polish banking sector was performed by Kliber and Pluciennik (2011a) as well as by Kliber et al. (2011), as well as Lu (2012). This article is the continuation and extension of the previous studies. First of all, we analyze the spread between the POLONIA rate and the reference rate in shorter periods which allows us to follow the changes of the effectiveness of the stabilization policy of the National Bank of Poland. We trace also the impact of several factors which seemed to lower the ability of the central bank to stabilize the POLONIA rate. The period of study is longer and covers the years: 2006–2012. The study is supported by the survey sent to the biggest commercial banks in Poland.

The remainder of the paper is as follows: first, we shortly describe the main goals of the monetary policy of the NBP. Next, we introduce the Confidence Package—one of the means through which the central bank tried to counteract the negative results of the crisis. In the following paragraph we shortly present the results of the survey sent to commercial banks. Eventually, we present the results of the econometric study on POLONIA dynamics. First, we briefly describe the behaviour of the spread in the context of domestic and international events. Next, we model conditional mean and variance of the spread, including pre-specified explanatory variables, reflecting the changes in monetary policy of the Polish central bank. We end the article with the discussion of the results.

2 Main goals of monetary policy of the National Bank of Poland (NBP)

According to Monetary Policy Guidelines published on annual basis by the NBP on its website,Footnote 1 the central bank has an obligation to maintain price stability. The primary instrument of the NBP is the short-term interest rate. The central bank strives to control the rate via its basic interest rates, i.e. the reference rate (determines the direction of the monetary policy and influences the level of market rates of maturities comparable to that of the basic open market operations), the deposit and lombard rates (determine the fluctuation band of overnight interest rates in the interbank market) and the rediscount rate (indirectly determines the interest on required reserve holdings).

The central bank manages liquidity in the interbank sector via the open market operations. Within the framework of these operations, the NBP issues the 7-day NBP bills every Friday. Additionally, the central bank can carry out the fine-tuning operations on irregular basis, issuing NBP bills of shorter maturity. Apart from the basic open market operations, the NBP provided also the standing facilities, allowing commercial banks to manage short-term liquidity using the marginal lending facility (lombard credit). Yet another instrument of the central bank’s monetary policy is the required reserve system. It is used to stabilize liquidity and reduce the short-term interest rates volatility. The commercial banks are obliged to maintain their required reserves with the central bank either on current accounts or on required reserve accounts (National Bank of Poland 2009).

Starting from 2008 the official key interest rate of the NBP is POLONIA—the market interest rate for unsecured, short term (overnight) interbank loans. However, based upon the level of the open market operation one can presume that the central bank aimed at steering POLONIA even since 2006. POLONIA is not an interest rate sensu stricto, but should be rather called an index. It was created at the initiative of ACI Polska (http://www.acipolska.pl) in order to set OIS (overnight interest rate swap) contracts. It is calculated—and published every day at 5 pm—as an average of overnight interest rates weighted by all the overnight transactions performed up to 4 pm during this day.

3 Confidence crisis in the Polish banking sector

The financial crisis started in US in 2007. In 2008 it spread onto the European financial market. First it was perceived in the developed countries, and a while later in the emerging markets. The crisis was accompanied with the decline of confidence in the banking sector.

In Poland the results of the financial crisis became visible in autumn 2008, after the collapse of the Lehman Brothers’. Although the phenomenon of liquidity surplus is specific to the Polish interbank sector, it was impossible to avoid importing the so called “confidence crisis” from the European market. In October, 14, 2008 the NBP decided to introduce the “Confidence Package” (described in details in the next paragraph) and supply yet additional liquidity to the banking sector. For instance, the Polish central bank decided to introduce REPO operations of maturity 6 days (17 October 2008) and 14 days (21 October 2008), as well as 3 months (November 2008).Footnote 2

3.1 Confidence Package

Together with the outbreak of the financial crisis, confidence in the Polish banking sector significantly decreased. Thus, in mid-October 2008 the NBP introduced the so-called “Confidence Package” in order to provide additional liquidity into the banking sector. There were three main goals of the Package:

-

enable commercial banks to obtain zloty for longer than 1 day;

-

enable banks to obtain foreign currencies;

-

increase the possibility to obtain zloty liquidity by banks by means of wider securities for operations with the NBP (2009).

Thus, within the framework of the Confidence Package, the NBP:

-

began liquidity-providing REPO operations;

-

announced that if necessary, the open market operations of higher frequency would be performed;

-

announced that the issue of the 7-day NBP bills would be maintained as the main instrument of liquidity absorbing;

-

began to carry out FX swaps;

-

introduced modifications to the operating system of the marginal lending facility (reduction of haircut while determining the security for the lombard credit and expanding the list of assets which may act as a security for the marginal lending facility with the NBP).

Introduction of the Confidence Package eventually allowed the central bank to restore confidence in the interbank market and to control POLONIA more effectively. In the study presented in the paper we will assess what elements of the Package and during which period were the most successful.

3.2 Supply of the NBP bills

The Lehman Brothers fall had a strong impact on the banking sector (National Bank of Poland 2009). In the situation of the confidence crisis, the banks’ demand for liquidity grew significantly. First of all, they were reluctant to invest their money for longer than overnight, and thus the long-term operations were limited (not only in the interbank market, but also with the central bank). According to National Bank of Poland (2009), at the beginning of the reserve maintenance periods, banks strived to hold even more of their assets than required on current account at the National Bank of Poland. Thus, they complied at an earlier stage with the reserve requirement. This phenomenon is called frontloading and was typical not only for the Polish market. Since the funds held with the NBP above the required level are not remunerated, the excess funds were placed with the central bank using standing deposit facility. In such circumstances it became difficult to forecast liquidity properly. Therefore, starting from October, 17, 2008 National Bank of Poland stopped publishing the supply of the weekly bills, in order not to allow for such a situation, when the supply could exceed the demand. Up to the late February 2009 the NBP supported the main refinancing instruments in the amount needed by the commercial banks (so called—period of passive liquidity management).

When the NBP stopped publishing the supply of the bills, the demand at first did not react but a while later started to grow. When the NBP returned to the so called active liquidity management, starting to publish the supply of the NBP bills during the tenders and trying to reduce the liquidity surplus in the banking sector, the commercial banks overreacted. Banks declared much higher demand for the bills than the supply was (overbidding), even if they would not be able to acquire as much bills as they called for. As a result, the central bank decided to increase the amount of bills available on tenders and the demand and supply again matched. (see also: Kliber and Płuciennik 2011a, b; Kliber et al. 2011).

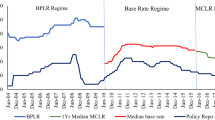

3.3 Interest rate policy

Similarly to the European Central Bank, the National Bank of Poland decided to revive the interbank market also via lowering its interest rates. Let us analyse the interest rate policy of the NBP before and during the crisis. We will focus on the main interest rate—the reference one. Let us stress that although the level of the interest rates has been changed several times during these years (see Fig. 1 for details), the interest rates corridor remained constant and equaled to 1.5 % (both in the case of lombard-reference, as well as reference-deposit rates).

In January 2006 the reference rate amounted to 4.50. During 2006 the interest rates were lowered twice: in February and in March. The year 2007 was the year of interest rates growth. This tendency ended in November 2008, when the Monetary Policy Council decided to lower the interest rates, after the fourth increases during the year. In 2009 the interest rates were lowered in January, February, March and June, while in 2010 their level was not changed. During the period over study, this was their minimum (the reference rate amounted to 3.50). In 2011, after the four increases, the interest rates returned to their levels from January 2006. The last increase, by 0.25 pt has been decided in May 2012.

3.4 Reserve requirements

Additionally to the abovementioned steps, the Polish central bank decided to lower the reserve requirement rate from the level of 3.5 % (set in 2003) to the level of 3 % (in May 2009). The purpose of maintaining the reserves is to smooth out the impact of movements of the liquidity in banking sector to the interbank interest rates, as well as to limit the liquidity surplus. In December 2010 the National Bank of Poland returned to the 3.5 % of the required reserve.

4 Assessment of the monetary policy by Polish commercial banks: the survey

We sent a survey to the head-quarters of the 68 Polish banks (excluding the cooperative ones), among all to the banks that serve as of Money Market Dealers (i.e. they are allowed to take part in open market operations of the central bank), in order to check their opinion on the effectiveness of the monetary policy of the central bank. We received answers from 32 of them (47 %). The group of respondents was diverse, encompassing the presidents and vice-presidents of the board, the head directors, accountants and experts from various divisions. Among the banks who answered the survey there were 9 (of 15) banks—Dealers of Money Market in 2011. Full version of the survey is available in (Płuciennik et al. 2013). Here, we summarize the main results of this part of the questionnaire, that apply to the liquidity management by the NBP.

In the survey we asked the banks about their opinion on the Confidence Package and importance of its separate elements. We asked them also to express their opinion about the decision to lower the required reserve rate and the NBP interest rates. Eventually we asked the banks to rate the effectiveness of the NBP in POLONIA stabilization during the years 2008–2009 and 2010–2011.

Most of the banks decided that the interest rates cuts in 2008 were too sharp and too fast. However, the majority of the respondents appreciated the decision to lower the reserve requirement rate. Let us stress the fact that liquidity surplus was still present in the market. On the other hand, it was difficult to obtain additional resources in the interbank market. Nevertheless, the banks were obliged to meet the reserve requirements. For security reasons, they aimed at cumulating the reserve prior to the deadline (frontloading), and thus lost opportunity to earn more. When the reserve requirements were cut, the frozen amount could have been lowered and thus, the banks rated the change positively. This decision could contribute to the gradual revival of the interbank transactions. Afterwards, frontloading did not appear so frequently, and the ability of the NBP to steer POLONIA rose.

When it comes to the Confidence Package, almost 80 % of the respondents expressed their positive opinion about its influence on the condition of the Polish banking sector. However, its elements were moderately appreciated among the banks that positively assessed the Package, and even the decision of the NBP to extend the list of assets that may have served as a security was graded very low.

Almost 70 % of the respondents decided that the NBP effectively stabilized POLONIA during the years 2008–2009, but less than a half noticed any improvement of the liquidity management during the years 2010–2011. Almost as many had no opinion on the subject. The banks explained their positive answers pointing out mainly the short-term fine-tuning operations (esp. during the last days of reserve maintenance period) and higher amount of deposits put with the NBP accounts. Some of the respondents mentioned also the fact that the deviations of POLONIA rate from the reference rate were diminished from 89 pts in 2009 to 43 pts in 2011.

5 Assessment of the monetary policy by Polish commercial banks: the econometric study

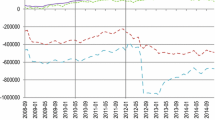

Based upon the previous research we are aware of the fact that the National Bank of Poland temporarily lost its ability to control POLONIA effectively, however this ability has been gradually won back. Previous studies, however, were conducted based upon the data sample ranging from January 2006 to June 2010, divided into two periods by the date of the Lehman Brothers fall (Kliber and Płuciennik 2011a) or three periods: 2006–2008, January 2008–September 2008 and October 2008–May 2010 (Kliber et al. 2011). Thus, we were not able to capture the effect of separate decisions of the central bank (such as change from active to passive liquidity management or imposing limits on NBP bills supply) as well as the separate out-of-the-country events (such as the Greek crisis) into the dynamics of POLONIA. However, based upon the Fig. 1 we can notice that the events indeed could have influenced the dynamics of the spread. Therefore, we decided to divide the sample into seven sub-periods, taking into account the internal and external events.

5.1 Division of the period over study and the spread dynamics in the obtained subperiods

-

Period I (02.01.2006–07.08.2007). This is the period during which the first signals of the crisis were observed, the debt of the US citizens grew and first financial institutions collapsed. During this period POLONIA was not officially announced as the key interest rate of the National Bank of Poland, however some spread characteristics suggest that POLONIA had been stabilized since the beginning of 2006 (see also: Kliber and Płuciennik 2011a). In the first sub-period the spread took small positive values. Such values are typical in the situation when the commercial banks, lending their assets to other banks, take into account the risk premium (see: Wuertz 2003; Hassler and Nautz 2008). In the whole period we observe a kind of periodicity of the POLONIA rate connected with the reserve-maintenance cycle.Footnote 3

-

Period II (08.08.2007–05.09.2008). During this period the markets experienced sharp decline of confidence. Lots of commercial banks applied for and received financial help in huge amounts (from Federal Reserves System, European Central Bank, etc.). The confidence crisis spread to Europe, however, it had not yet been perceived in Poland. Starting from 2008 the National Bank of Poland officially identified the control over POLONIA rate as its operational goal. At the beginning of the second period the spread characteristics changed. Declines of POLONIA values are deeper and more persistent. In April 2008, after the nationalization of the Northern Rock and selling the Bear Sterns bank we observe an increase of the POLONIA volatility. However, it does not seem to follow directly any of the mentioned events. As we mentioned previously, the confidence decline in the interbank market was a gradual process, and a consequence of the global confidence crisis.

-

Period III (05.09.2008–19.02.2009). In this period the financial crisis became a fact. On September, 15th, the Lehman Brothers collapsed. The confidence crisis gained its peak. In October the National Bank of Poland implemented the Confidence Package. Starting from October, 17, the NBP decided not to limit the supply of its bills during weekly auctions, but supply them in the amount covering the full demand. This was the beginning of the period of the so called “passive monetary policy” or “passive liquidity management”. In the third period increase of POLONIA volatility is much more visible, and connected with the aforementioned underbidding. POLONIA rate used to take much lower values than the reference rate, and at the end of the maintenance periods its values were closer to the deposit rate. Due to frontloading, the price of overnight money declined and the spread widened (see: National Bank of Poland 2009).

-

Period IV (20.02.2009–27.05.2009). Starting from February, 20, the NBP returned to the active liquidity management and again started to limit the supply of its bills during weekly auctions. As a consequence, commercial banks artificially increased their demand for bills. Since it was impossible for banks to invest all the money in the secure NBP papers, supply of the overnight money increased and the POLONIA rate decreased, taking values close to the deposit rate.

-

Period V (28.05.2009–23.04.2010). This was the period of the relative stability of the financial markets all over the world. In the Polish interbank market, however, the situation was not yet stable (high underbidding in November and December). Yet, at the beginning of 2010 the liquidity situation in the interbank market started to improve (National Bank of Poland 2010). At the beginning of the fifth period the absolute values of the spread increased again, as a result of the underbidding. This phenomenon is explained by the willingness of the banks to demonstrate their high liquidity level in the half-year balance-sheets. Such situation repeated also in July and August 2009. It was a consequence of the rapid liquidity growth in the banking sector. The banking sector again experienced an increase in the level of short-term liquidity, caused by the purchase of foreign currency by the NBP and from exchange of foreign currency to the Polish zloty (carried by the Ministry of Finance at the NBP)—see: National Bank of Poland (2011b). Moreover, from December 2008 to December 2009 the level of currency in circulation decreased by 1,470 million PLN. Commutation of these factors resulted in lowering the POLONIA rate to the deposit rate level.

-

Period VI (24.04.2010–13.06.2011). This was the period during which the Greek problems became apparent to the whole Europe (first aid packages, and change of bond ratings to junk level). When it comes to the Polish interbank market, the improvement observed in the first half of 2010 was discontinued. The underbidding was much more frequent, since the banks instead of placing the surplus in the 7-days NBP bills, kept the liquidity buffer in their own accounts. The interbank transactions were limited, the liquidity surplus grew. In December 2010 the National Bank of Poland launched the short-term fine-tuning operations on an ad-hoc basis within the required reserve maintenance period, in order to affect the liquidity conditions prevailing in the banking sector. The values of the spread increased, although its volatility was much lower.

-

Period VII (14.06.2011–31.05.2012). In this period the crisis from Greece was transmitted also to the other South-European countries. The yield of Italian bonds grew, hitting the 7 % limit. The same was true in the case of the Spanish bonds. At the end of the year 2011 the European Bank conducted the first from the three planned Long-Term Refinancing Operations (further: LTRO) in order to supply the commercial banks with low-interest capital, while at the end of February 2012—the second one. In Poland, starting from the second half of 2011 the situation in the interbank market improved and the deviation of the POLONIA rate was reduced to levels seen only before the collapse of Lehman Brothers (National Bank of Poland 2011a). From June 2011 the fine-tuning operations introduced in December 2010 were supplemented by fine-tuning operations at the end of the maintenance period, with the overnight maturity. Fine-tuning operations of this type enabled banks to balance their own liquidity position over the entire reserve maintenance period (National Bank of Poland 2011a). As a result the banks limited their usage of deposit facility. In 2012, as the National Bank of Poland continued its policy, the confidence in the interbank market grew (National Bank of Poland 2012). POLONIA rate remained at much lower level than the reference rate and its volatility was less dynamic.

In Table 1 we present the descriptive statistics of the spread in the analyzed periods. The average value of the spread was always negative, what means that the POLONIA rate was always lower than the reference rate (see also Fig. 1). In the third period (when the central bank stopped publishing the supply of the bills and actually the banks were able to obtain the bills with no limits) we observed the highest standard deviation, while the highest kurtosis was present in the first period. We observe also that the skewness was negative in all the periods, apart from the fourth (when the NBP returned to the active liquidity management) and fifth one (a period of relative stability in the financial markets).

The authors realize that some sub-periods are short and therefore some of the results could have been biased. Thus, to test stationarity and unit root, we used the robust tests (of high statistical power for short samples), particularly the bootstrap test of Davidson (2009) and the non-asymptotic tests: Augmented Dickey–Fuller test (Said and Dickey 1984), Philips–Perron test (Phillips and Perron 1988) and Elliott–Rothenberg–Stock test (Elliott et al. 1996).

The results of stationarity and unit-root tests show that only in the fourth period the spread is not stationary. The results of the tests are unanimous. Only the bootstrap test of Davidson (2009) reject the hypothesis of stationarity for periods III, V, VI, VII. The construction of the test implies that it rejects the null hypothesis also in the case when long memory is present in the data (see Davidson 2009). The KPSS and V/S test the null hypothesis of stationarity against the alternative of a unit root and do not take into consideration the case of fractional integration of the process (Table 2).

5.2 Analysis of the spread dynamics

Due to the length of the samples we decided to concentrate our analysis on linear dependencies of the spread changes. If the ARCH test (Engle 1982) for standardized residuals revealed heteroscedasticity, we modeled the nonlinear dependencies via SV model (see the “Appendix” for details). Based upon the findings in the literature (Wuertz 2003; Linzert and Schmidt 2008; Schianchi and Verga 2006; Abbassi and Nautz 2010), as well as our previous findings (Kliber et al. 2011; Kliber and Płuciennik 2011a) we decided to use the following explanatory variables:

-

3mwos—spread between 3-month WIBORFootnote 4 and OIS of the same maturity; represents the aversion to lending in the interbank market;

-

1wois_ref—spread between the weekly OIS and reference rate; represents the expectations about the future dynamics of short rates;

-

var_1wois—variance of weekly OIS; measure of the uncertainty associated with overnight rate (in our case it was a squared return of OIS);

-

btcratio—bid to cover ratio; variable taking value of 1 in case of underbidding and in the opposite case: ratio of the supply of NBP bills to the demand;

-

ctbratio—equals 1 in the case of overbidding while in the opposite case—the ratio of the supply to the demand for NBP billsFootnote 5;

-

df_lf—difference between the balance of the end-of-the day deposit to the balance of lombard credit; represents the surplus of supply over demand for money in overnight;

-

binary variables indicating:

-

(end_of_the_year) end of the year,

-

(end_of_half_year) end of the half-year,

-

(d_reqRes) last day of reserve maintenance period,

-

(d_reqRes01) a day before the last day of reserve maintenance period,

-

(d_mo) a day of the main operations,

-

(underbid) a day of the main operations when underbidding occurred,

-

(overbid) a day of the main operations when overbidding occurred.

-

Below, we present the results of the study (see also: Table 3). We would like to point out that the periodicity of POLONIA was proven by the model in each sub-period. End_of_year dummies were significant in each sub-period apart from the fourth one. In the fifth period the periodicity is visible through the significant dummies: end_of_half_year and the lagged dummy end_of_year. The fourth period was in fact so short that it did not comprise neither the end of year nor end of half year, but the periodicity was also visible through the dummies indicating the end of reserve maintenance period. The dummy (or lagged dummy) proved to be significant also in all the remaining sub-periods. The same conclusions apply to the dummy d_mo indicating the day of main operation (every Friday), which is significant itself, or its lagged value, in each period apart from the fourth one. However, in the first three sub-periods in the day of main operation the spread widened, while in the last three—the spread narrowed prior to the day of main operations.

The variables connected with expectations (difference between OIS and reference rate) were also significant in each period, while the variable representing uncertainty associated with overnight money (var_1wois or its lagged value)—in the first, fourth and fifth ones. Positive relationship between expectations and POLONIA means that the market participants believed that POLONIA would behave according to expectation. It is worth noting that the variable 1wois_ref was positive in the whole period. This suggests that the investors expected future growth of the short rate. Therefore, we conclude that the investors believed also that POLONIA would come closer to the reference rate and thus, that it would stabilize. We observe, however, that the parameter at the lagged value of the variable was negative in the third and fifth periods. This can be explained by the asymmetrical fluctuations of POLONIA.

If we investigate the autocorrelations of the POLONIA process, the first values are negative. Explanation of this phenomenon can be as follows: due to liquidity surplus and reluctance of the banks to lend for longer periods, the supply of overnight money exceeded the demand. In such situation POLONIA comes close to deposit rate, and the commercial banks prefer to invest their surplus in the interbank market. However, during the confidence crisis lots of banks were unable to allocate their money in the interbank market. Thus, they placed their surplus as the end-of-the-day deposit with the central bank, diminishing the supply of the money. As a result POLONIA rose. Again, when it was much higher than the deposit rate (5–10 basis points), it made the end-of-the-day deposit more attractive to commercial banks. The period of the cycle was however longer than a day, and thus, we observe the negative autocorrelations of POLONIA, as well as the opposite sign of parameters at the lagged explanatory variables.

Direct relationship between uncertainty (var_1wois) and POLONIA spread was negative. The uncertainty about the interest rate level made the commercial banks bid irrationally low to obtain the NBP bills. In turn, the low yield of the bills made the term structure downward-sloping, and in consequence—narrowed the POLONIA spread. The negative value of the parameter obtained in the model is thus justified. The opposite sign of the parameter at the lagged value of the variable can be again explained by the cyclical behavior of POLONIA described above.

The variables connected with the supply of NBP bills (ctbratio and btcratio) were significant in each period, apart from the third and fourth ones (in the third one the NBP sold as many bills as to cover the whole demand, while in the fourth the banks artificially increased their demand to obtain as many bills as possible). Counterintuitive, in the first two sub-periods the relationship between btctatio and the spread was negative, and became positive only starting from the fifth sub-period. The negative relationship found in the first sub-periods can be explained again by underbidding, the occurrence of which suggested the loss of control over POLONIA by the NBP. The banks were reluctant to obtain the bonds and lose their liquidity for the whole week, but instead invested only in the overnight instruments. Together with the end of the confidence crisis (the ending sub-periods) the relationship became positive, as expected (see also: Linzert and Schmidt 2008). In the case of the model for conditional mean, the variable ctbratio was significant only in the seventh period and the sign of the coefficient was negative (which is consistent with our expectations). The variable was also significant in the volatility equation for the first and second period, but its relationship with volatility was negative in the former, but positive in the latter case.

The df_lf variable representing the surplus of supply over demand for money in overnight was significant in each periods but fourth one, however, due to the scale, it took very small values, most often close to null. The sign of the parameter at the explanatory variable is, as expected, negative. When the supply of overnight money was high, the price of the overnight money should go down, and the POLONIA spread widened.

Eventually, the variables 3mwois and overbid were not significant in any period, neither as the explanatory variables in conditional mean, nor in variance.

Although in the first period the National Bank did not officially control POLONIA, the instruments of monetary policy did affect the rate. We observe that the variables: btcratio and its lagged value, the day of the main operation as well as the variable connected with the difference between the supply and the demand for the overnight money: df_lf significantly influenced the spread. However, as we already noticed, the relationship between the spread and btcratio was in this period negative. The fact can be explained by the very large difference between the supply and the demand for the NBP bills, resulting in underbidding. Commercial banks artificially increased their demand, and since it could not have been fulfilled, the surplus must have been invested in the interbank market. In consequence, the supply of the “short money” was higher than the demand for it and POLONIA went lower (see also Fig. 1). In the case of levels and volatility, we observe also significant impact of periodicity—through the variables indicating end of year, end of half year, the day of the main operation (conditional mean equation) as well as the end of reserve maintenance period (both conditional mean and variance). Volatility of the spread was also affected by the variable ctbratio.

Similar conclusions can be derived regarding the second period, although in the case of volatility we do not observe any impact of periodicity-connected variables. The mean-reverting parameter ϕ was high, which means that after a shock, volatility came back to its mean value relatively fast. Moreover, in the second sub-period the long-memory parameter in conditional mean proved to be significant. Its negative value can be interpreted as yet another sign of periodicity (see the “Appendix” for details).

In the third period, when the central bank run the passive liquidity management, the spread was affected mainly by expectations, variables connected with periodicity and with liquidity management (df_lf). Only the day of main operation remained to be the significant variable. This can suggest that the amount of demand for money and the amount of money in the interbank market affect the market itself.

The situation changed in the fourth period. First of all, the autocorrelation in the spread could have been fully explained only through the AR model with fractional integration. The positive long memory parameter suggests that the National Bank was unable to manage the POLONIA rate. High persistence of the spread and the long-lasting impact of shocks makes it difficult for the short rate to perform its signaling role (see also: Nautz and Scheithauer 2011). In the presence of long memory, the effect of shock was persistent and the National Bank of Poland was unable to contradict them. In the opposite case, the effect of shock disappeared shortly afterwards, and the central bank was able to control the short rate. The impact of expectations and the uncertainty associated with the overnight rate were significant. Significance of uncertainty can be explained by the fact that that when the central bank returned to active liquidity management, the bank reacted very nervously (and declared excessively high demand for NBP bills). Thus, the central bank had to rise the supply and the situation stabilized already in the next—fifth period. Indeed, we observe a significant impact of all variables that influenced POLONIA in the first periods. However, the uncertainty associated with the overnight rate was still present (the lagged variable var_1wois). This uncertainty disappeared already in the sixth period. In the both sub-periods we notice significant impact of underbidding (the variable underbid) on the dynamics of POLONIA, and at the same time the relationship between the variable btcratio and the spread was positive.

Periods VI and VII were the ones of higher risk of transmission of Greek crisis to another market in the form of the subsequent confidence crisis. In Poland the central bank decided to run the short-term fine-tuning operations, first in December 2010 in order to improve the situation. Again, we observe the significant impact of expectations on the spread dynamics, as well as the variables connected with the ratio of supply and demand during the tenders. In the seventh period for the first time the variable ctbratio affected the spread. Let us remind that in the seventh period the central bank run its fine-tuning operations and the significance of the variables can prove also the significant impact of these operations on the dynamics of the spread.

Starting from the fifth sub-period, not only the variables associated with liquidity management became significant again, but also the long memory disappeared from the spread. The variable associated with liquidity management: df_lf became significant. Starting from the fifth sub-period we also observe a positive impact of the day of main operation, prior to which the spread narrowed. Thus, we can suppose that starting from the fifth period the central bank regained its ability to influence the dynamics of POLONIA (Table 3).

6 Summary

In the article we analyzed the effectiveness of the Polish central bank to counteract the negative effects of the financial crisis. In assessing the NBP policy we took into account two criteria: the results of the survey sent to commercial banks, as well as the results of the econometric study on the ability of the bank to steer POLONIA rate. The situation in the Polish interbank market was exceptional—contrary to the western European case, the Polish market was experiencing liquidity surplus. However, together with the financial crisis, there came the confidence breakdown. Thus, Polish commercial banks for security reasons stopped interbank transactions of maturity longer than 7 days and decided to accumulate liquidity surplus. In order to improve the situation, the National Bank of Poland decided to implement so called Confidence Package. Moreover, following the Central Bank, the Monetary Policy Council decided to run a series of interest rate cuts, as well as lowered the level of required reserve. From October 2008 to February 2009 the NBP managed liquidity passively. At the same time, the central bank tried to effectively manage its key rate: POLONIA.

Polish commercial banks positively assessed the stabilization policy of the central bank and the Confidence Package. They appreciated the interest rates cut, although viewed them as too sharp and too fast. Most of the banks appreciated lowering the level of required reserves, as well as the fine-tuning operations at the end of the reserve maintenance period. Most of them also quite positively assessed the ability of the central bank to stabilize POLONIA, but the majority noticed no difference of the effectiveness of the NBP policy between the periods 2008–2009 and 2010–2011.

Yet, based upon the presented research we conclude that together with the outbreak of the financial crisis, the central bank gradually lost its ability to stabilize POLONIA rate. Commercial banks not only maintained significant liquidity surpluses on their current accounts, but at the same time they aimed to fulfill the reserve requirements prior to the deadline (frontloading). Underbidding, often observed during tenders, indicated inability of the central bank to sterilize the liquidity surplus (introducing money bills with maturity shorter than 1 week also did not bring the expected results). Supply of the overnight money was higher than demand for it, and thus POLONIA rate declined and almost reached the level of the deposit rate (at that time in the eurozone banks lacked liquidity in the interbank market, and as a result EONIA rate exceed the rate of main operations of ECB).

Together with the stabilization in the international market, the central bank regained its ability to effectively manage POLONIA. The study suggests significant impact of the Confidence Package on the stabilization in the market. However, it seems that the Greek debt crisis again intensified the nervousness among commercial banks. Introduction of fine-tuning operations at the end of reserve maintenance period (commercial banks obtained additional possibility to place the liquidity surplus in the central bank) helped to stabilize the situation in the market, although the liquidity surplus was still present. Due to this liquidity surplus, the ability of the NBP to manage POLONIA has not returned to the level from before the crisis.

In the econometric model presented in the article, the variables connected with the ratio of supply and demand during the period overlapping with Greek debt crisis proved to be statistically significant and their relationships with the spread become positive. The day of the main operation positively affected the spread, and starting from the sixth sub-period the uncertainty associated with overnight money stopped to influence the spread. This means that the central bank operations influenced the spread POLONIA-reference rate and suggest that the ability of the NBP to steer POLONIA was not totally lost.

Taking into account the results of both parts of the studies, we conclude that although the central bank experienced the problems with stabilization of POLONIA at the beginning of the crisis, the means undertook by the bank to counteract these difficulties were the right ones. They allowed to calm the nervousness in the interbank market and gradually to gain control over POLONIA.

Notes

The maturity of standard REPO operations equals 7 days.

In Poland the central bank uses so called averaged required reserve framework. If a bank obtains the required level of reserves earlier, it can invest its surplus in the local interbank market, to gain additional profit. On contrary, if at the end of the reserve-maintenance period it appears that the bank did not maintain enough money on the current account with the central bank, it needs to find additional resources in the interbank market. Both situations result in the jump of the POLONIA rate (respectively: the negative and the positive one).

WIBOR—Warsaw Interbank Offered Rate—the interest rate at which Polish banks are willing to lend money to another banks for a specific term. The rate is quoted by 14 banks (so called money market dealers, selected by the NBP), every business day, at 11 am. The average of the quotation is the WIBOR rate. The banks are obliged to enter the transactions at the WIBOR rate for a short period of time after the quotation. In this sense the WIBOR rate is the transactional one (for more details see—ACI Polska webpage).

Linzert and Schmidt (2008), in order to explain the dynamics of EONIA spread, used a variable bid-to-cover ratio which is defined as the ratio between the total bid volume of monetary bills and the amount covered. It is interpreted as a degree to which the liquidity surplus is absorbed by the central bank. The part of the surplus not absorbed by the central can be invested in the interbank market, which affects the money supply in the interbank market and in turn influences the interbank rates levels. Therefore, we expect a positive relationship between the spread and the bid-to-cover ratio. However, as explained in (Kliber and Płuciennik 2011a), the idea of Linzert and Schmidt (2008) proves correct under the assumption that the underbidding does not occur in the monetary bills auction. Underbidding causes a decrease in the spread, but when it occurs the value of bid-to-cover ratio is the highest. Therefore, similarly to (Kliber and Płuciennik 2011a) we decided to introduce the two variables: btcratio and ctbratio.

We are aware of the fact that the two-step estimation is not as efficient as the one-step estimation. However, due to computational complexity we decided to use this approach.

If needed we include also the long memory parameter into the conditional mean equation.

References

Abbassi P, Nautz D (2010) Monetary transmission right from the start: the (dis)connection between the money market and the ECB’s main refinancing rates. SFB 649 discussion paper 2010-019

ACI Polska webpage: www.acipolska.pl/english.html

Beirne J (2011) The EONIA spread before and during the crisis of 2007–2009: the role of liquidity and credit risk. J Int Money Finance 31(3):534–551

Beirne J, Caporale GM, Spagnolo N (2010) Liquidity risk, credit risk and the overnight interest rate spread: a stochastic volatility modeling approach. Discussion papers of German Institute of economic research no. 1029

Davidson J (2009) When is a time series I(0)? In: Castle J, Shepherd N (eds) Chapter 13 of the methodology and practice of econometrics. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Doman M, Doman R (2004) Ekonometryczne modelowanie dynamiki polskiego rynku finansowego [Econometric modelling of the Polish financial market]. Poznan University of Economics Press, Poznań

Ejerskov S, Moss CM, Stracca L (2003) How does the ECB allot liquidity in its weekly main refinancing operations? A look at the empirical evidence. ECB working paper no. 244

Elliott G, Rothenberg TJ, Stock TJH (1996) Efficient tests for an autoregressive unit root. Econometrica 64(4):813–836

Engle RF (1982) Autoregressive conditional heteroskedasticity with estimates of the variance of United Kingdom inflation. Econometrica 50:987–1007

Giraitis L, Kokoszka P, Leipus R, Teyssière G (2003) Rescaled variance and related tests for long memory in volatility and levels. J Econom 112:265–294

Hassler U, Nautz D (2008) On the persistence of the eonia spread. Econ Lett 101:184–187

Kliber A, Płuciennik P (2011a) An assessment of monetary policy effectiveness in POLONIA rate stabilization during financial crisis. Bank Credit 4:5–29

Kliber A, Płuciennik P (2011b) Risk premium in the short rate market - comparison of the Polish and European markets behaviour during the crisis. Ekonometria (Econometrics) 31:132–142

Kliber A, Kliber P, Płuciennik P (2011) The control of Polonia rate by Polish Central Bank - Empirical Analysis (in Polish). In: Jajuga K, Ronka-Chmielowiec W (eds) Inwestycje finansowe i ubezpieczenia - tendencje swiatowe a rynek polski, vol 183, pp 194–204

Kwiatkowski D, Phillips PCB, Schmidt P, Shin Y (1992) Testing the null hypothesis of stationarity against the alternative of a unit root. J Econom 54:159–178

Kwiatkowski J (2000) Bayesian analysis of long memory and persistence using ARFIMA models with application to Polish stock market. Dyn Econom Models 4:199–210

Linzert T, Schmidt S (2008) What explains the spread between the euro overnight rate and the ECB’s policy rate. ECB working paper no. 983

Lu Y (2012) What drives POLONIA spread in Poland? IMF working paper 12/215, International Monetary Fund

Meyer R, Yu J (2000) BUGS for a Bayesian analysis of stochastic volatility models. Econom J 3:198–215

Moschitz J (2004) The determinants of the overnight interest rate in the euro area. ECB working paper no. 393

National Bank of Poland (2009) Report on monetary policy implementation in 2008. NBP, Warsaw

National Bank of Poland (2010) Annual report 2010. Banking sector liquidity. Monetary Policy Instruments of the National Bank of Poland. NBP, Warsaw (http://nbp.pl/en/publikacje/instruments/instruments2010.pdf)

National Bank of Poland (2011a) Annual report 2011. Banking sector liquidity. Monetary Policy Instruments of the National Bank of Poland. NBP, Warsaw (http://nbp.pl/en/publikacje/instruments/instruments2011.pdf)

National Bank of Poland (2011b) Report on monetary policy implementation in 2010. NBP, Warsaw

National Bank of Poland (2012) Annual report 2012. Banking sector liquidity. Monetary policy instruments of the National Bank of Poland. NBP, Warsaw (http://nbp.pl/en/publikacje/instruments/instruments2012.pdf)

Nautz D, Offermanns CJ (2007) The dynamic relationship between the euro overnight rate, the ECB’s policy rate and the term spread. Int J Finance Econ 12(3):287–300

Nautz D, Scheithauer J (2011) Monetary Policy Implementation and Overnight Rate Persistence. J Int Money Finance 30(7):1375–1386

Panigirtzoglou N, Proudman J, Spicer J (2000) Persistence and volatility in short-term interest rates. Bank of England working paper 116

Phillips PCB, Perron P (1988) Testing for a unit root in time series regression. Biometrika 75:335–346

Płuciennik P, Kliber A, Kliber P, Piwnicka M, Paluszak G (2013) Influence of the world financial crisis 2007–2009 onto the Polish interbank market (in Polish), National Bank of Poland Working Papers 288, pp 5–128

Said ES, Dickey DA (1984) Testing for unit roots in autoregressive-moving average models of unknown order. Biometrika 71:599–607

Schianchi A, Verga G (2006) A theoretical approach to the EONIA rate movements. SSRN working paper series. doi:10.2139/ssrn.906793

Tsay RS (2010) Analysis of financial time series. Wiley, London

Vila Wetherilt A (2003) Money market operations and short-term interest rate volatility in the United Kingdom. Appl Financ Econ 13(10):701–719. doi:10.1080/0960310022000020898

Wuertz FR (2003) A comprehensive model of the euro overnight rate. European Central Bank working paper no. 203

Acknowledgments

The research was supported by the National Bank of Poland, through the project “Wpływ światowego kryzysu gospodarczego 2007–2009 na rynek międzybankowy w Polsce” (Influence of the world financial crisis 2007–2009 onto the Polish interbank market) (2012). Some results presented in the research are also presented in the report (working paper) from the project (Płuciennik et al. 2013).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The views in this paper should be regarded as those of the author, and do not necessarily reflect those of the National Bank of Poland.

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 Model AR-SV: specification and estimation

Let us denote by y t the value of the process at time t. The AR–SV model has the following form:

with θ 0 ∼ N(μ, σ 2 υ ), where x 1,…, x l are the explanatory variables in the conditional mean equation, while z 1, …, z m are the explanatory variables of conditional variance of y. The latent variable θ t describes volatility at time t. The parameter μ describes the stationary value of θ (excluding the influence of the explanatory variables z 1, …, z m )—the variable θ has the tendency to return to this value. The standard deviation of error term ɛ displays the tendency to return to the value \( \exp \left( {\frac{\mu }{2}} \right). \) The parameter \( \phi \in \left( { - 1, 1} \right) \) is interpreted as the speed of return of θ to its mean (mean-reverting parameter). The distribution of errors in the volatility Eq. (3) is described with the precision parameter τ, which is a reciprocal of standard error.

We follow the procedure described by Tsay (2010) and (Doman and Doman 2004) and first determine the linear dependencies in the model (1).Footnote 6 Thus, we estimate the AR(k) model with explanatory variables.Footnote 7 The model (2)–(3) is estimated for standardized residuals obtained from the AR model.

In order to estimate the SV model we utilize the Bayesian methodology, assuming that both the parameters of the model: \( \mu ,\phi ,c_{ 1} , \ldots ,c_{m} ,\tau \) and the latent variables θ 0,…,θ N are stochastic variables. The estimation is then reduced to the problem of finding the posterior densities of the variables based upon their prior densities as well as the observed: ɛ 1,…,ɛ N .

For further details we refer the Reader to Meyer and Yu (2000). Estimation of SV model was performed using OpenBugs program of Meyer and Yu (2000). First 10 000 iterations were treated as the “burn-out” period, while next 10,000—as the sample from the posterior distribution. Estimation of conditional mean was performed in OxMetrics 6.1 program.

1.2 Long memory

Let us denote by y t the value of the process at time t. If the process under study is covariance stationary, we denote it by I(0). In such a case, the influence of the shock disappears after a limited number of periods, and this number is specified by the number of lags in ARMA process. If the process has a unit root, we denote it by I(1). In such a case, the effect of the shock lasts forever.

There exists also a class of processes, in which case the effect of the shock is persistent and disappears longer than in the case of the short-memory processes. We describe such a phenomenon as “long memory”, and such a process is called a fractionally integrated one (denoted by FI(d)). The ARFIMA model describing behavior of such a process has the following form:

where y t denotes the time series at time t, μ y —its mean and \( \Phi \left( L \right) = 1 - \phi_{1} L - \cdots - \phi_{p} L^{p} \) is the stable autoregressive polynomial in the lag operator L, and \( \Theta \left( L \right) = 1 + \theta_{1} L + \cdots + \theta_{q} L^{q} \)—the invertible moving average part (p, q ∊ {0, 1, 2, …}).

The long memory is governed by the part (1 − L)d. If d is an integer, the I(d) is non-fractional and taking dth differences of y t leads to I(0) process. If \( d \in \left( {0,0.5} \right), \) the process is said to exhibit long-memory property, and its partial correlations and autocorrelations decay monotonically and hyperbolically to zero, as the lag increases. If d ∊ (−0.5, 0) we have the process of so called intermediate memory. If d = 0 the process is covariance stationary (see: Kwiatkowski 2000).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Kliber, A., Kliber, P., Płuciennik, P. et al. POLONIA dynamics during the years 2006–2012 and the effectiveness of the monetary Policy of the National Bank of Poland. Empirica 43, 37–59 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10663-015-9287-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10663-015-9287-1

Keywords

- Monetary policy

- Central bank

- Financial crisis

- Interest rates

- POLONIA

- Stochastic volatility

- Interbank market