Abstract

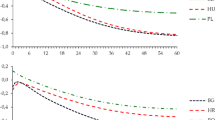

In the current context of continuous reassessment of the sustainability of the single currency and gradual enlargement of the euro area during the last decade, the objective of this research is to obtain new insights into the factors that determine the synchronisation of shocks in the Central and South-Eastern European countries vis-à-vis the euro area. The research contributes to the previous work by making a novel use of error correction model in a dynamic panel context which is extended by adding several important omitted variables related to the trade structure and policy coordination. We find that an increase in trade intensity, intra-industry trade and financial integration leads to less frequent asymmetric shocks. On the other hand, divergent fiscal policies are estimated in some model specifications to increase the shock divergence process, although the estimated impact is rather small to counteract the positive effects associated with trade and financial integration. The identified relationships in this research are affected by the significant trade and growth slowdown in the crisis period; while the global economic turmoil has boosted a demand shock convergence, its impact on the supply shocks is in the opposite (diverging) direction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The variable for output composition is not included explicitly in the model due to two main reasons. First, its effects are expected to be reflected by the trade structure. Lee et al. (2004) estimate that if both a variable for trade structure and a variable for output composition are included together in the model, only a variable for trade structure is statistically significant in explaining synchronization of business cycles. Clark and van Wincoop (2001) and Otto et al. (2003) find that output composition has significant effects, but it is dominated by the trade structure. Second, there are no available quarterly data for output structure of substantial number of countries in our sample.

Slovenia was the first country from the CSEE joining the euro area in 2007, followed by Cyprus and Malta in 2008, Slovakia in 2009 and Estonia and 2011.

From an econometric point of view, Greene (2008, p. 469) offers forcible arguments for the importance of modelling dynamics, as: ‘adding dynamics to a model […] creates a major change in the interpretation of the equation. With the lagged variable, we now have in the equation the entire history of the right-hand-side variables, so that any measured influence is conditional on this history; in this case, any impact of the independent variables represents the effect of new information’.

Data sample starts in q1:1996 for Malta, q1:1997 for Bulgaria, Croatia, Macedonia and Serbia, and q1:1998 for Romania.

The results obtained from ADF tests are not presented here due to space limitation but are available upon request to the authors.

This approach was followed by Dibooglu and Horvath (1997) as well.

On theoretical grounds, the horizontal intra-industry trade is assumed to be more consistent with the modern theories of trade and relevant to trade among developed countries, whereas vertical intra-industry trade is expected to be more related to traditional theories of comparative advantage and to dominate the trade among countries with different income levels (so called North–South trade models). As Greenaway et al. (1995) demonstrate a failure to separate the two components can seriously undermine the interpretation of the empirical results. Not only horizontal and vertical intra-industry trade are driven by different factors, but also the adjustment implications of a given trade expansion differ between the two.

The unit values for exports and imports are obtained by dividing the values of exports and imports by their quantity.

Fontagné and Freudenberg (1997) estimate the share of intra-EU trade flows according to the degree of overlap (the minority flow as a percentage of the majority flow) and find that the highest value is for a threshold of 10 % (almost one-third of all intra-EU trade). Regarding the share of intra-EU trade flows according to the unit value ratios of bilateral trade flows (measured by dividing the larger unit value by the smaller one), the highest value is for the threshold of 15 % (more than a quarter of total intra-EU trade).

The difference in change of cyclically adjusted government budget balance (surplus or deficit) measured as a percentage of country’s GDP, between the CSEEC and the euro area is used as a robustness check.

Sources of the data employed in the analysis include Eurostat (data for budget balances and foreign direct investments), Eurostat Comext database (data for intra-industry trade), IMF’s International financial statistics (data for prices, output, interest rates and real effective exchange rates), IMF’s Direction of Trade statistics (data for trade intensity) and the statistics agencies and central banks of the respective countries for data that were not available from previous sources.

Due to statistical insignificance of the monetary policy coordination proxy and a dummy for the euro area membership in the core model regressions, these variables are omitted and we rely on more parsimonious specifications in the robustness checks. Nevertheless, the obtained results are consistent if these variables are included and are available upon request to the authors.

The variables for supply and demand shocks are also re-estimated only for the quarterly observations in the pre-crisis period (q2:1997–q2:2008).

References

Artis JM, Fidrmuc J, Scharler J (2008) The transmission of business cycles: implications for EMU enlargement. Econ Transit 16(3):559–582

Babetskii I (2005) Trade integration and synchronization of shocks. Econ Transit 13(1):105–138

Bayoumi T, Eichengreen B (1993) Shocking aspects of European monetary unification. In: Giavazzi F, Torres F (eds) Adjustment in the European monetary union. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 193–230

Blackburne EF, Frank MW (2007) Estimation of nonstationary heterogeneous panels. Stata J 7(2):197–208

Blanchard O, Quah D (1989) The dynamic effects of aggregate demand and supply disturbances. Am Econ Rev 79(4):655–673

Boone L (1997) Symmetry and asymmetry of supply and demand shocks in the European Union: a dynamic analysis. CEPII Working Paper No. 97/03

Boone L, Maurel M (1999) Economic convergence of the CEECs with the EU. Centre for Economic Policy Research Discussion Paper No. 2018

Calderon C, Chong A, Stein E (2002) Trade intensity and business cycle synchronization: are developing countries any different? Central Bank of Chile Working Paper No. 195

Chamie N, Deserres A, Lalonde R (1994) Optimum currency areas and shock asymmetry: a comparison of Europe and the United States. Bank of Canada Working Paper No. 94-1

Clark TE, van Wincoop E (2001) Borders and business cycles. J Int Econ 55:59–85

Darvas Z, Szapary G (2004) Business cycle synchronization in the enlarged EU: comovements in the new and old members. National Bank of Hungary Working Paper No. 2004/1

Darvas Z, Rose AK, Szapary G (2005) Fiscal divergence and business cycle synchronization: irresponsibility is idiosyncratic. NBER Working Paper No. 11580

Dées S, Zorell N (2011) Business cycle synchronisation, disentangling trade and financial linkages. European Central Bank Working Paper No. 1322

Dibooglu S, Horvath J (1997) Optimum currency areas and European monetary unification. Contemp Econ Policy 15(1):37–49

Eichengreen B (1992) Should the Maastricht treaty be saved? Princeton University, Princeton Studies in International Finance No. 74

European Community Commission (1990) One market, one money. European economy No. 44

Falvey R (1981) Commercial policy and intra-industry trade. J Int Econ 1(4):495–511

Fidrmuc J (2004) The endogeneity of the optimum currency area criteria, intra-industry trade, and EMU enlargement. Contemp Econ Policy 22(1):1–12

Fidrmuc J, Korhonen I (2003) Similarity of supply and demand shocks between the euro area and the CEECs. Econ Syst 27(3):313–334

Fontagné L, Freudenberg M (1997) Intra-industry trade: methodological issues reconsidered. CEPII Working Paper No. 97-01

Fontagné L, Freudenberg M (1999) Endogenous symmetry of shocks in a monetary union. Open Econ Rev 10(3):263–287

Fontagné L, Freudenberg M, Gaulier G (2005) Disentangling horizontal and vertical intra-industry trade. CEPII Working Paper No. 2005-10

Frankel AJ, Rose A (1998) The endogeneity of the optimum currency area criteria. Econ J 108:1009–1025

Frenkel M, Nickel C (2002) How symmetric are the shocks and the shock adjustment dynamics between the Euro area and Central and Eastern European countries. International Monetary Fund Working Paper No. 02/222

Frenkel M, Nickel C, Schmidt G (1999) Some shocking aspects of EMU enlargement. Deutsche Bank Research Research Note RN 99-4

Greenaway D, Hine R, Milner C (1995) Vertical and horizontal intra-industry trade: a cross industry analysis for the United Kingdom. Econ J 105:1505–1518

Greene WH (2008) Econometric analysis, 6th edn. Pearson-Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River

Greene WH (2012) Econometric analysis, 7th edn. Pearson-Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River

Grubel HG, Lloyd P (1975) Intra-industry trade. Macmillan, London

Haldane AG, Hall SG (1991) Sterling’s relationship with the dollar and the Deutschemark: 1976–89. Econ J 101(406):436–443

Hamilton J (1994) Time series analysis. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Harvey AC (1989) Forecasting, structural time series models and the Kalman filter. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Harvey AC (1993) Time series models, 2nd edn. Harvester Wheatsheaf, New York

Imbs J (1999) Co-fluctuations. Centre for Economic Policy Research Discussion Paper No. 2267

Imbs J (2004) Trade, finance, specialization, and synchronization. Rev Econ Stat 86:723–734

Kalemli-Ozscan S, Sorensen BE, Yosha O (2001) Economic integration, industrial specialization, and the symmetry of macroeconomic fluctuations. J Int Econ 55:107–137

Kenen P (1969) The optimum currency area: an eclectic view. In: Mundell R, Swoboda A (eds) Monetary problems of the international economy. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp 41–60

Krugman P (1993) Lessons of Massachusetts for EMU. In: Giavazzi F, Torres F (eds) Adjustment in the European monetary union. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 241–269

Lee J, Park C, Shin K (2004) A currency union for East Asia. In: Asian Development Bank (ed) Monetary and financial integration in East Asia: the way ahead, vol 1. Palgrave Macmillan, New York

Otto G, Voss G, Willard L (2003) A cross section study of the international transmission of business cycles. University of Victoria, Canada, Mimeo

Pesaran MH, Shin Y (1997) An autoregressive distributed lag modelling approach to cointegration analysis. Paper presented at the Symposium at the Centennial of Ragnar Frisch, The Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters, Oslo, March 3–5, 1995, http://www.econ.cam.ac.uk/faculty/pesaran/ardl.pdf

Pesaran MH, Smith R (1995) Estimating long-run relationships from dynamic heterogeneous panels. J Econom 68:79–113

Pesaran MH, Smith R, Im KSI (1996) Dynamic linear models for heterogeneous panels. In: Mátyás L, Sevestre P (eds) The econometrics of panel data: a handbook of the theory with applications. Advanced studies in theoretical and applied econometrics 33, 2nd edn. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, pp 145–198

Pesaran MH, Shin Y, Smith R (1999) Pooled mean group estimation of dynamic heterogeneous panels. J Am Stat Assoc 94(446):621–634

Roodman D (2009) How to do xtabond2: an introduction to difference and system GMM in Stata. Stata J 9(1):86–136

Shin K, Wang Y (2005) The impact of trade integration on business cycle co-movements in Europe. Rev World Econ 141:104–123

Suppel R (2003) Comparing economic dynamics in the EU and the CEE accession countries. European Central Bank Working Paper Series No. 267

Zhang Z, Sato K (2005) Whither currency union in greater China? Yokohama National University, Centre for International Trade Studies Working Paper No. 2005-01

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the Center for Economic Research & Graduate Education-Economics Institute (CERGE-EI) under a program of the Global Development Network (GDN). All opinions expressed are those of the authors and have not been endorsed by CERGE-EI or the GDN. The views expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bank of the Republic of Macedonia, the University American College Skopje and the Ss. Cyril and Methodius University. The authors would like to thank the reviewers and participants at the conference in Prague organized by CERGE-EI in 2012 and Branimir Jovanović for helpful comments and discussions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Veličkovski, I., Stojkov, A. Is the European integration speeding up the economic convergence process of the Central and South-Eastern European countries? A shock perspective. Empirica 41, 287–321 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10663-014-9247-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10663-014-9247-1