Abstract

This study focuses on the analysis of cryptocurrency regulatory developments in Europe. The aim is to review national crypto-legislation in Europe and the EU's latest initiative to create designated regulatory instruments for the crypto-economy. This study assessed whether the European Union's Regulation on Markets in Crypto-Assets (MiCA) would have the intended effect. Drawing on the results of a survey of crypto experts from five European countries, this study evaluated the effectiveness of current regulation across Europe and how it can be improved to reduce financial crimes. The findings show that a unified national legal framework for regulating transactions with crypto assets does not exist in European countries. Current crypto regulations are dictated by anti-money laundering recommendations. This study provides suggestions for improving MiCA regulation. The article offers recommendations for an international regulatory standard for crypto assets and insights for increasing efficiency in regulating DeFi, NFTs, and smart contracts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Cryptocurrencies originated in 2009 (with the emergence of Bitcoin) as a new financial paradigm outside the realm of traditional financial institutions and centralised intermediaries (Europol, 2021). Cryptocurrencies are underpinned by blockchain technology, a distributed ledger that records transactions across numerous nodes, thus ensuring transparency and security while eliminating the need for centralised authorities such as banks and other financial intermediaries (BIS, 2023). The fundamental nature of cryptocurrencies lies in their use of cryptographic methods to secure transaction integrity, control the creation of additional units, and verify asset transfers (Emmert, 2022).

Blockchain technology has proliferated, revolutionising many sectors over a short timeframe. Despite its rapid growth, regulators failed to keep pace with this innovation in terms of its understanding, providing appropriate legal and regulatory frameworks (Kerrigan et al., 2023). Regulators and policymakers have been on a journey to understand and develop adequate regulatory approaches to crypto assets, tokens, and distributed ledger technologies (DLTs). Consequently, legal and regulatory uncertainties led to significant obstacles to blockchain innovation (Kafteranis & Turksen, 2021).

The unique characteristics of cryptocurrencies and blockchain technology require regulatory approaches, particularly in the European context, where the need for harmonisation of regulation is palpable. The decentralised and borderless nature of cryptocurrencies poses challenges to traditional regulatory frameworks, which are often limited within national jurisdictions. Criminals actively use FinTech capabilities for illicit purposes and financing criminal activities. The cryptocurrency ecosystem became a Petri dish for criminals, as tracking and preventing illegal cryptocurrency transactions is a complex process (Benson et al., 2023).

Crypto regulation at the European Union (EU) level has been lethargic and has slowed blockchain innovation. However, with limited success, some European countries have tried to address this independently, primarily by applying existing legal frameworks to blockchain technologies (LexisNexis, 2022).

The article aims to analyse the national crypto-legislation of European countries that have developed bespoke laws to create an entirely new legal architecture and principles to enable the token economy. Additionally, we review the EU's latest initiatives, highlighting the challenge of regulating evolving blockchain technology across European jurisdictions.

The study highlights that national legislation and the proposed MiCA regulation in the EU fail to cover all groups of crypto assets, particularly NFTs and DeFi. A more comprehensive regulation is suggested to address these areas.

This research emphasises the importance of developing an international standard for regulating crypto assets to enhance the effectiveness of regulations and promote global cooperation in addressing illicit activities in the crypto ecosystem.

This study highlights the difficulties in regulating DeFi transactions due to anonymity, automation and the absence of intermediaries. Standardising smart contracts while considering consumer rights and introducing specific approaches for regulating financial transactions to minimise risks are recommended.

2 Background

Cryptocurrencies, with their inherent anonymity and decentralised features, pose a considerable risk of illicit transactions, such as money laundering and financing of terrorism (Europol, 2021). Anti-money laundering (AML) regulations struggle to trace these digital currencies effectively, as they operate outside traditional banking systems and often lack transparent, traceable transaction histories (Javaid et al., 2022; Benson et al., 2023). This makes enforcement and compliance complex for regulatory authorities.

Money laundering is the main criminal activity associated with the illicit use of cryptocurrencies (Europol, 2021). The volume of illicit crypto transactions rose in 2022 to an all-time high of $20.1 billion (Chainanalysis, 2023). The share of all cryptocurrency activity associated with illegal actions doubled in 2022 compared to that in the previous year—from 0.12% in 2021 to 0.24% in 2022 (Chainanalysis, 2023). The need for robust regulation to prevent illegal activities, such as money laundering and terrorism financing, and to protect consumers from fraud and hacking is a key theme in the extant cryptocurrency literature (Kakushadze & Rosso, 2018). Current academic debates (Dupuis & Gleason, 2020; Benson et al., 2023; Huang, 2021; Morton, 2020; Skirka et al., 2000; Salami, 2021) call for a regulatory framework to balance these concerns while promoting innovation and competition in the cryptospace.

The study on creating a regulatory framework for regulating cryptocurrencies in the EU (Winnowicz et al., 2022) points to an ad-hoc approach to regulating cryptocurrencies in Europe. The authors analysed the regulatory effectiveness and linked the impact of notifications about changes in the regulation with the prices of popular cryptocurrencies, particularly bitcoin. Determining the impact of regulatory acts on the dynamics of cryptocurrency prices is one of the options for analysing the effectiveness of crypto regulation.

Sandner et al. (2022) analysed the best practices of regulating cryptocurrencies in Liechtenstein. They highlight Liechtenstein's efforts to classify tokens, taking into account the technical and innovative nature of cryptocurrencies, which are different from securities. In addition, the authors note the practical approach of the Liechtenstein authorities in determining the ownership of tokens because, unlike countries such as the USA, the United Kingdom (UK), Germany, and France, Liechtenstein has introduced a definition of a "person who has the right to dispose of the tokens". The term "property" cannot be applied to crypto assets because of its technical and novel nature. In another publication (Ferreira et al., 2021), the authors provide a detailed analysis of the existing European practices for stablecoin regulation and emphasise the need to apply the principle of "same business, same risks, same rules" during the formation of a single European regulatory system for crypto assets.

A significant barrier to formulating clear crypto regulation is the lack of explicit, common terminology for crypto assets. Various definitions for cryptoassets are used in different countries, often interchangeably and without a specific classification. There is no explicit definitional agreement at the international level or, for many countries, even at the national level (PwC, 2023). In the U.S., for instance, crypto assets are subject to the financial markets supervisor's decision on whether they qualify as a security, commodity, currency or something else (Hallak & Salén, 2023). Numerous cases have proven that such classifications could vary, creating legal uncertainty (Nolasco & Vaughn, 2021). For example, Bitcoin is usually not considered to be a security in the U.S. The Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) views Bitcoin as a currency and determines its regulatory mechanism according to the Bank Secrecy Act (BSA) (Fletcher et al., 2021). The Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) regards Bitcoin as a commodity, citing the Commodities Exchange Act (CEA) for regulatory purposes. The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) Chair Gary Gensler believes that most cryptocurrencies are securities, based on the Howey Test, which comes from a 1946 Supreme Court ruling in the SEC v. W.J. Howey Co. (Duggan, 2023). Ethereum's classification has changed from a security to a commodity, and it may again come under the SEC authority due to the possibility of earning interest in these tokens. This ongoing debate reflects the lack of a consistent federal crypto asset framework, resulting in a fragmented market with diverse state-level regulations (Hallak & Salén, 2023).

Fletcher et al. (2021) published a global review of crypto regulation. They concluded that, due to its unique characteristics, Bitcoin (and other cryptocurrencies) does not fit easily into any existing U.S. legal and regulatory frameworks such as the BSA, CEA, or Securities Act. The researchers suggest that cryptocurrencies be considered a technology within the FinTech industry and regulated by private sector technology companies through a three-tiered framework. The authors acknowledge the difficulty in achieving international consensus on self-regulation and the potential to misuse cryptocurrencies for illicit activities. Classifying cryptocurrencies as technology and adopting a global, bottom-up regulatory approach could promote anti-money laundering/counter-terrorist financing (AML/CTF) measures while integrating underbanked individuals who rely on alternative financial services into the global financial system (Fletcher et al., 2021).

Given the borderless nature of crypto assets, another critical area is the need for international coordination and cooperation in regulating cryptocurrencies. Many authors argue that patchwork of national regulations is ineffective, creates additional risks, and calls for the development of a global regulatory framework. Another study (Emmert, 2022) noted that the main problem in regulating cryptocurrencies is the lack of comprehensive classification and identification at the legislative level. Creating a single state regulatory authority that regulates cryptocurrencies and the activity of issuers, users, miners, investors and trading platforms in this area would improve the legal environment. The study concludes that an agreement regulating cryptocurrencies and their mandatory ratification by all countries is necessary.

The issue of the global consensus on crypto regulation and aspects of the use of crypto assets is addressed in the paper by Shinde (2022). The author proposes to develop a uniform Initial Coin Offering (ICO) regulation for cryptocurrencies and risk management related to the crypto ecosystem at the G20 level as an initial step toward forming a global regulatory mechanism in this area. The work by Morton (2020) substantiates the need to form a unified system of regulatory rules and authorities. The author proposes to empower these authorities to apply sanctions and impose criminal charges to strengthen cyber security and combat illegal activities when using crypto assets. The extant literature is actively debating on issues related to forming the basis for developing global rules and global conventions for regulating cryptocurrencies. Such approaches must be implemented in practice because the heterogeneity of national legislation on crypto regulation, or its complete absence, creates opportunities for using crypto assets for money laundering, fraud and other illegal operations.

Researchers highlight the technical challenges of cryptocurrency regulation, such as blockchain transaction tracking and user identification. Some authors suggest using know-your-customer (KYC) and anti-money-laundering (AML) rules, while others suggest using blockchain analysis techniques to track transactions. In particular, Dupuis and Gleason (2020) explore the illicit use of cryptocurrency through Kane's normative dialectic paradigm. They identified several ways to exchange cryptocurrencies for fiat money that are still available to those seeking to launder money using digital coins. The authors recommend increased KYC requirements for crypto transactions, as well as the creation of central bank-backed digital coins, possibly coupled with a ban on the use of cryptocurrency for commercial transactions. Doing so would undermine the utility of non-fiat digital coins for money laundering purposes.

Salami (2021) analysed issues related to implementing the KYC/AML principles for regulating decentralised finance (DeFi), which potentially carries significant money laundering risks and is also practically unregulated. The author shows successful practices around DeFi regulation in the U.S. and suggests to using financial criteria that reflect DeFi turnover and the number of transactions. The uniqueness of DeFi technology, which requires regulation to be built into DeFi protocols, should be considered. This approach may involve building KYC requirements into the actual protocol and verifying that a central bank digital currency (CBDC) equivalent backs the stablecoin.

Zetzsche et al. (2020) suggest that DeFi necessitates regulation to accomplish its fundamental objective of decentralisation. Moreover, they argue that DeFi can to create an entirely novel method of developing regulation, known as 'embedded regulation'.

Other researchers (Malkoc et al., 2021) suggest that blockchain technology's decentralised nature complicates traditional regulatory methods' effectiveness and that regulators should focus on creating a legal framework for smart contracts and decentralised applications instead.

Despite the active debate around problematic aspects of crypto regulation, both in theory and in practice, a robust regulatory and legal framework at the global level has yet to be established.

Therefore, this research aims to systematise the best national practices of normative and legal regulation of cryptocurrencies and to form a pool of policy alternatives for crypto assets regulation at the global level.

3 Proposed evaluation model

European legislation does not provide a coherent legal basis for regulating crypto assets effectively. Current regulatory authorities are not empowered to oversee the crypto-asset market, which opens up opportunities for money laundering and other financial crimes. Increasing the effectiveness of regulatory operations with crypto assets is possible by means of international regulatory rules, conventions and agreements. Our primary research question addressed in this paper is as follows:

What is the state of European regulation on cryptocurrencies and crypto assets, and what levers can increase the effectiveness of legal regulation of crypto assets to minimise cases of money laundering, tax evasion and other financial crimes?

Drawing from the literature on cryptocurrency regulation (Dupuis & Gleason, 2020; Emmert, 2022; Ferreira et al., 2021; BaFin, 2020; Morton, 2020; Salami, 2021; Sandner et al., 2022; Shinde, 2022), we propose the following model to identify the main problems and gaps in the legislative field.

Six hypotheses are proposed, as reflected in Fig. 1:

H1

A single regulatory body enhances the effectiveness of the EU Cryptocurrency Regulation.

H2

EU-wide harmonised legislation will positively increase the effectiveness of the EU Cryptocurrency Regulation.

H3

The classification of crypto assets enhances the effectiveness of the EU Cryptocurrency Regulation.

H4

The rules for licensing crypto asset operators enhance the effectiveness of the EU Cryptocurrency Regulation.

H5

The recognition of cryptocurrencies as legal tenders is vital for the efficient regulation of cryptocurrencies.

H6

An effective EU Cryptocurrency Regulation minimises the misuse of crypto assets, such as through money laundering and financing of terrorism.

4 Methodology

To address the research questions, we analysed the national regulatory instruments of selected countries coupled with a survey of cryptocurrency experts. Respondents from European countries with developed legislation regulating crypto assets, such as France, Germany, the United Kingdom, Italy and Liechtenstein, were selected for the expert survey. This allowed us to explore the national experiences in cryptocurrency regulation and formulate recommendations for creating a pan-European legal environment.

The content of the questionnaire (Appendix 1) was developed based on the analysis of literature on the regulation of cryptocurrencies (Benson et al., 2023; Dupuis & Gleason, 2020; Emmert, 2022; Ferreira et al., 2021; BaFin, 2020; Morton, 2020; Salami, 2021; Sandner et al., 2022; Shinde, 2022) to identify gaps in the legislative field.

The questionnaire for the survey included three blocks of questions, which reflected the opinions of experts on the following key topics: (1) identification of the main problems in the sphere of regulation of cryptocurrencies; (2) assessment of the current effectiveness of cryptocurrency regulation; and (3) determination of directions for improving the effectiveness of cryptoregulation in Europe. Each block of the questionnaire included four questions, which helped reveal the researched issues in more detail for both the respondents and the researchers.

The questionnaire used a Likert scale (Jotform, 2022) ranging from 1 to 5 (where 1 stood for totally disagree, and 5—meant completely agree).

The estimated value of the answers to one specific question is calculated according to formula (1):

where xqn—the value of the answers according to the n-th question in the questionnaire; an—the number of respondents who answered 'totally disagree'; bn—the number of respondents who answered 'disagree'; cn—the number of respondents who answered 'neither agree nor disagree'; dn—the number of respondents who answered 'agree'; fn—the number of respondents who answered 'completely agree'; N1—the number of respondents who answered the question. The value of the indicator is expressed as a percentage.

Participants in the cryptocurrency market (managers of centralised crypto exchanges (CEXs), developers and managers of crypto projects, and active members of crypto forums) were contacted for survey completion. These contacts were reached through social media channels such as Telegram, LinkedIn and Facebook (over 2000 invitations to participate in the survey were sent).

The responses were screened for quality assurance, and the total number of fully completed and usable responses was 300. The final pool of expert responses was obtained from five European countries (France, Germany, the UK, Italy and Liechtenstein).

The demographics of the respondents were 216 men (72%) and 84 women (28%); the average age of all respondents was 37 years. This demographic distribution reflects a predominant male representation in the cryptocurrency field (Aju & Burrell, 2023).

The data were collected between January and March 2023. To maintain the validity and reliability of the data, the main principles of data collection were as follows: use of various sources of information, obtain informed consent, ensure confidentiality and anonymity, preserve the chain of evidence, minimise biases, and analyse and discuss the findings.

Analysis of the legal framework for the regulation of cryptocurrencies was carried out according to the following criteria: (1) recognition and classification of cryptocurrencies in the country; (2) availability of special legislation; (3) the presence of a particular state institution for the regulation and supervision of crypto assets; (4) approaches to the analysis and assessment of risks, in particular, the risks of liquidity and volatility of value, investment risk, risks of money laundering and terrorism financing, and fraud risks; (5) procedure for taxation of operations with crypto assets; and (6) the level of responsibility for violations of legislation in the cryptocurrency field.

Based on the crypto regulatory framework analysis, the best European practices of such regulation were determined, and proposals were developed to improve the effectiveness of crypto regulation at the supranational level.

5 Results

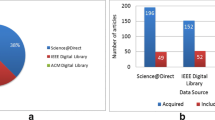

With respect to H1: Crypto experts in France, Germany, the UK, Italy, and Liechtenstein were surveyed to determine experts' views on crypto regulation. As such, from H1 (having a single regulatory body within the EU framework) to H4 (rules for licensing of crypto asset operators), the level of efficiency of the regulatory system of each studied country was compared. The results of the survey are shown in Figs. 2, 3 and 4.

The data in Fig. 2 show that respondents from all surveyed countries chose "lack of a clear classification of cryptocurrencies and crypto assets" as the main problem in the sphere of crypto regulation. This confirms that the lack of a precise classification of cryptocurrencies and crypto assets complicates the application of existing regulatory acts to regulate the crypto market.

With respect to H2, respondents attributed cryptocurrency regulation's other weakness to the "lack of harmonised legislation". Some countries have complex and fragmented regulatory rules, with different authorities having jurisdiction over crypto assets (Money Gate, 2023). There are also no harmonised rules at the pan-European level. Therefore, this leads to additional risks for cryptocurrency market participants, including the state, which is exposed to risks such as money laundering and tax evasion.

The next problem chosen by the respondents is the lack of a single regulatory body empowered to regulate and scrutinise crypto-asset transactions. Assigning supervisory functions and regulating cryptocurrencies to non-specialised supervisory bodies reduces the effectiveness of such regulation. In addition, an equally important problem of the crypto-legal framework is the lack of clear rules and requirements for licensing activities involving transactions with crypto assets.

A survey on the effectiveness of current legal frameworks in selected countries allowed us to conclude that France's and Liechtenstein's legal systems are the most effective (Fig. 3).

With respect to H3, the survey results show that respondents from France and Liechtenstein express the most profound concern about their national legislation, which lacks a comprehensive classification of crypto assets, the creation of clear rules of activity in the crypto market and the licensing of this activity. A regulatory environment that reduces the use of cryptocurrencies for money laundering is also evident. Moreover, it is worth noting that the respondents from all the countries answered the fourth question about AML legislation positively. This choice can be explained by the fact that the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) has already developed clear rules for combating money laundering and terrorist financing at the supranational level, which were implemented in national legal acts (FATF, 2023).

With respect to H5, the question of recognising cryptocurrency as a legal tender (Fig. 3) indicates that none of the countries under study has legally recognised cryptocurrencies (or one of them). In our view, the non-recognition of highly capitalised cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin, Ethereum or Tether as the legal means of payment complicates the formation of the regulatory framework.

5.1 National regulation analysis

France: As of January 2023, the French regulatory framework, unlike those of other countries under study, offers a broad classification of cryptocurrencies, namely: a digital asset that includes two subcategories (utility tokens and virtual currencies), stablecoins and security tokens (O'Roker & Lourimi, 2023). Cryptocurrencies can be classified as securities under AMF regulations (AMF, 2020). If a cryptocurrency is deemed to meet the definition of security, it is subject to the same regulations as traditional securities.

The French classification of crypto is incomplete because the classification of non-fungible tokens (NFTs) and DeFi is not considered. However, the AMF, as the French financial market regulation authority, emphasises that NFT regulation can be carried out depending on the token characteristics. In some cases, NFT may be subject to digital assets.

Germany: Cryptocurrencies are classified as financial instruments (Stamm & Meinert, 2022). Unlike France, Germany's legislation defines only the concept of crypto assets (without proper classification), which follows from the directives and recommendations of the financial authorities of the European Union.Footnote 1 Crypto assets are defined as digital representations of value not issued or guaranteed by the central bank or any government authority and are not necessarily tied to any legal currency (BaFin, 2022). Crypto assets do not have the legislative status of money. Nevertheless, they can be accepted by any natural or legal entity as a means of exchange and can be transferred, stored and traded electronically. As such, crypto assets are subject to the same regulations as other financial instruments, including securities, derivatives, and investment funds (Stamm & Meinert, 2022).

Italy: The regulation of cryptocurrencies in Italy lacks legal authority. Italian legislation does not specify the definition of 'cryptocurrency' (Donna & Vella, 2023). Additionally, there are no approved rules for regulating either blockchain or cryptocurrencies in general. Moreover, the use, exchange and storage of different cryptocurrencies are not prohibited (Donna & Vella, 2023). Italian law views crypto assets as financial products rather than as financial instruments. Accordingly, the regulation of crypto assets is simplified.

Despite insufficient crypto regulation, Italy imposed AML and KYC requirements on crypto exchanges and wallet service providers (Lener et al., 2022). It should also be noted that in court cases and activities of the Central Bank of Italy, the Directives of the European Union are used (in particular, EU Directive 2016/0208 – the AML 5 Directive) (Donna & Vella, 2023).

Notably, for countries that do not have their own legislation on crypto regulation, the external rules of authorities such as the FATF and the European Union are fundamental. This approach helps countries lacking national regulation form legislation and provides critical aspects for effective crypto regulation.

UK: The leading financial regulatory body is the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA), and operations with crypto assets are regulated primarily by FCA (2019). The FCA works closely with other regulatory bodies (the Bank of England and the Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA)) to ensure that the UK's approach to crypto regulation is comprehensive and practical (GOV.UK, 2023).

In the UK, as in France, the classification of crypto assets was carried out at the policymaking level by the UK Cryptoasset TaskforceFootnote 2 (Cryptoassets Taskforce, 2018). However, unlike France, the United Kingdom has recognised 'exchange tokens' that use a DLT platform. They are not issued or backed by a central bank or other central authority and do not provide the rights or access that security or utility tokens provide (Huang, 2021). They are used as a medium of exchange or for investment.

In addition, in the UK, other types of tokens, such as security tokens, software tokens and electronic money tokens, meet the definition of electronic money under the Electronic Money Regulation (EMR) (Huang, 2021).

At the same time, there is no dedicated legal framework (as of May 2023) for regulating crypto assets in the United Kingdom, which leads to fragmented coverage of crypto activities. For example, even though the UK Cryptoassets Taskforce defines exchange tokens as a type of crypto asset, transactions with such tokens are not regulated by the Bank of England (participant in the working group). The Bank of England does not recognise exchange tokens as a means of exchange or payment (Kerrigan et al., 2023).

The UK follows the rules for combating money laundering and terrorist financing in regulating operations with crypto assets based on the EU's fourth and fifth AML directives on money laundering and terrorist financing (Kerrigan et al., 2023). Under these directives, virtual currency exchanges and custodian wallet providers are considered 'cryptocurrency businesses' and must register with the FCA and comply with AML regulations (FCA, 2022).

It can be seen that UK regulation of transactions with crypto assets contains many gaps. In particular, the exchange tokens were not recognised by the Bank of England as legal tenders. It does not regulate purchase and sale agreements through the mediation of cryptocurrencies. In addition, the UK legislation does not contain clear rules for regulating NFTs and DeFi.

Liechtenstein: The regulation of crypto asset transactions is based on the Liechtenstein Token Act (Nägele, 2020). The main feature of this law is the definition of ownership of tokens, which cannot be property in the traditional sense. For this purpose, the legislature introduced the concept of a key, which allows the disposal of tokens since the token itself cannot be owned because it is assigned to a particular address in the DLT. Thus, to eliminate legal conflicts regarding the ownership of tokens, the law proposed the term "person entitled to dispose of the token" as equivalent to "the person who owns the token". The introduction of this term is also aimed at preventing the use of stolen tokens and their keys. For this purpose, the Token Act contains requirements for registering subjects carrying out transactions with crypto assets (Nägele, 2020).

All other operations with crypto assets, such as ICOs, are not regulated by the Liechtenstein Token Act since Liechtenstein is a member of the European Monetary Union. Therefore, the financial market is regulated under EU directives (Singh, 2020).

Moreover, introducing the term "the person who has the right to dispose of the token" significantly simplifies the identification of individuals and legal entities that can carry out transactions with cryptocurrencies. However, the crypto regulation in Liechtenstein, like the legislation of the other countries under study, does not regulate transactions with NFTs or decentralised finance. This reduces the effectiveness of the Liechtenstein legislation and increases money laundering risks in this area.

In conclusion, harmonising the regulation of operations with crypto assets across Europe is paramount for those involved in the crypto market. Currently, European countries have different rules and approaches to regulation. While the EU recognises the need to standardise international regulations to combat money laundering and terrorist financing, its cryptocurrency regulatory activities have been slow and fragmented.

5.2 EU regulation

In relation to H1, as of April 2023, the EU has yet to adopt a legal instrument for crypto assets across its borders. Nonetheless, several measures have been proposed by the EU Commission to regulate these digital assets and prevent their misuse for money laundering and terrorist financing activities. These measures include the Sixth Anti-Money Laundering Directive (6AMLD), which requires crypto-asset service providers to register with national authorities, adhere to anti-money laundering regulations and report suspicious transactions.Footnote 3 Additionally, the EU has proposed a set of rules known as the Markets in Crypto-Assets Regulation (MiCA) (Europarl.europa.eu, 2022a). The 6AMLD seeks to address gaps in domestic legislation across EU Member States by harmonising definitions of money laundering and virtual assets across all EU nations.

One of the primary effects of the 6AMLD is that all companies regulated under it must adopt a risk-based approach to preventing and reporting crime and developing technological procedures under EU 6AMLD requirements (Finance.ec.europa.eu, 2021).Furthermore, companies must have sufficient technology capacity to conduct processes such as KYC. A total of 22 predicate offences were identified, including, most notably, cybercrime, digital crime, tax crime, insider trading and market manipulation, and environmental crimes (Benson & Adamyk, 2022). All companies and organisations must establish safe KYC procedures and be able to identify these types of crimes (LexisNexis, 2022).

To establish a universal approach to regulating operations with crypto assets in the territory of the EU, the European Commission developed the Regulation of the European Parliament and the Council on Crypto-asset Markets and Amending Directive (EU) 2019/1937 (Europa.eu, 2022). This set of rules, known as MiCA, seeks to create an oversight framework for crypto assets, including regulations for issuers, service providers and secondary market participants (Europarl.europa.eu, 2022a).Footnote 4

The primary objectives of this regulation are: (1) to provide more clarity on reducing the risks of fraud, hacking and market abuse, as well as to explain the consistency with the upcoming revision of the anti-money laundering legislation; (2) to better explain the problems of financial stability related to "stablecoins" and clarify how supervisory authorities will ensure the protection of investors and consumers (Europa.eu, 2022).

This regulation ensures crypto asset traceability while providing a regulatory framework for digital asset businesses for the first time. This legal document establishes a uniform field of activity and regulates the operations of various players in the cryptocurrency market (crypto exchanges, issuers of crypto assets, virtual assets service providers).Footnote 5

MiCA focuses on establishing compliance between the definition of "crypto assets" and the definition of "virtual assets" outlined in the recommendations of the FATF (FATF, 2023). This approach proves that regional and national regulatory bodies in financial markets are guided by international (global) documents and rules on combating money laundering, emphasising the importance of creating a global convention to regulate transactions with crypto assets.

The MiCA framework applies to crypto assets not yet regulated by other EU financial legislation (Borg et al., 2022). MiCA rules provide legal certainty for market participants and encourage innovation in a single market with a new EU passport for cryptocurrency service providers (Adamyk & Benson, 2023).

Nevertheless, the MiCA regulation will not provide a comprehensive framework of the crypto asset market, as it defines only three types of crypto assets to which the rules cover, i.e.: (1) crypto assets that are intended to provide digital access to goods or services available in DLT and that are accepted only by the issuer of this token ("utility tokens"); (2) tokens related to assets, i.e. tokens that aim to support a stable value by referring to several currencies that are legal tender, one or more goods, one or more crypto assets or a basket of such assets (including stablecoins backed by commodities, or one or several currencies); and (3) electronic money tokens—crypto assets intended mainly as the means of payment aimed at stabilising their value by reference to only one fiat currency (stablecoins backed by a single fiat currency) (Van der Linden & Shirazi, 2023).

MiCA regulation effectively rules out the use of algorithmic stablecoins. It also forces stablecoins backed by fiat currencies to adhere to strict requirements, including maintaining a liquid reserve with a 1:1 ratio to stablecoin. The comprehensive framework of MiCA extends beyond these initial measures, encompassing a range of additional obligations for stablecoin issuers. These include implementing robust procedures to protect backing and reserve assets, establishing mechanisms for addressing complaints, and safeguarding against market abuse and insider trading (Europarl.europa.eu, 2022a). MiCA requires a designated reserve of assets, separate from other operational assets, to be maintained. This reserve must be held in custody by an independent third party, ensuring an added layer of security and transparency in the stablecoin ecosystem (Europarl.europa.eu, 2022b). Such measures indicate the EU's proactive attitude toward establishing a regulated and secure environment for the growing sphere of digital assets.

Due to its lengthy legislative process and rapid developments in the virtual and asset markets, MiCA still requires updating even though it has not yet taken effect. For instance, its rules do not address some recent innovations such as DeFi, non-fungible tokens and non-transferable tokens (Kafteranis & Turksen, 2022). The decentralised nature of DeFi and the lack of a central entity pose possible challenges. The MiCA regulation does not explicitly mention DeFi. Nonetheless, there have been suggestions to indirectly address this issue by implementing rules that apply to stablecoins, which are crucial for executing DeFi protocols and regulating digital asset service providers (Eurofi, 2022).

To propose ways to expand regulatory influence on all existing groups of crypto assets, it is important to consider another result from our questionnaire (Fig. 4).

As shown in Fig. 4, respondents called for an international, global approach to regulating operations with crypto assets. On the other hand, there is already positive experience in the regulatory environment of operations with crypto assets by the FATF, which at the global level has developed rules to combat money laundering using cryptocurrencies.

6 Discussion

An analysis of national legislation regulating operations with crypto assets and MiCA proposals shows that neither national legislation nor legislation of the EU covers all groups of crypto assets with regulatory rules, particularly NFTs and DeFi.

A first step toward forming a future global approach to regulating operations with crypto assets should be the development of an international standard for the regulation of the crypto asset market (Morton, 2020; Shinde, 2022). The United Kingdom and the EU already have experience with national-level regulation. Based on the EU, UK and US studies on regulating operations with crypto assets, the convention should consider the key points summarised in Appendix 2.

Particular regulatory attention should be given to the specifics of NFT operations because the existing legislation and MiCA do not provide sufficient clarifications regarding procedures for regulating this type of crypto assets. However, one of the starting points for the regulation of NFTs may be the proposal of the Law Commission of England and Wales to define NFTs as a third category of personal property—a data subject (Moyle et al., 2022). Validating the NFT value minimises the risk of overvaluing NFTs as digital artwork and, therefore, reduces money laundering.

Particular attention should be given to developing concepts for regulating decentralised finance and smart contracts. While noting the progress made in regulating centralised crypto markets, we also observe a notable absence: regulations for DeFi transactions still lack consideration of anonymity and the absence of intermediaries. While all DeFi transactions involving cryptocurrencies are governed by rules applicable to centralised intermediaries, none of these properties (anonymity and absence of intermediaries) are considered. Given that DeFi transactions are usually anonymous, it is quite difficult to create a legal framework and determine to whom to apply sanctions, for example, if DeFi market projects do not have legal registration.

Regulators are faced with a complex problem—the modern system of regulation (centralised finance) is based on the presence of intermediaries whose activities are regulated and who are required to control their clients' transactions. Regulating centralised crypto exchanges followed a similar path, with requirements becoming similar to those applied to banks—particularly regarding anti-money laundering.

A DeFi ecosystem is a closed system that rarely interacts with traditional finance. The DeFi market is decentralised and borderless. Its participants do not interact with centralised financial institutions. At the same time, participants in the DeFi ecosystem are anonymous, and do not need to identify themselves.

For regulators, the anonymity of transactions is a significant problem. In the case of DeFi transactions, it is practically impossible to block user accounts that have received suspicious funds. For example, if such funds were received because of an exchange (swap) on decentralised platforms (DEXs), the recipient does not know whom they received the funds from. Even if they wanted, the account holder could not identify from whom they received the questionable funds. Accordingly, bringing the recipient to justice is impossible, and there is no legal ground for blocking their accounts.

It is pretty tricky to interpret the legal norms introduced in the MiCA unambiguously regarding the prohibition of the issuance of cryptocurrency if the issuer is not legally registered and does not have legal status or licence.

For DeFi projects, such norms cannot be applied. Most DeFi projects do not have a specific governing body to which MiCA regulations can be applied. Management in most DeFi projects is carried out collectively by small anonymous ownership of governance tokens. However, there is not a single governing body. Of course, it is possible to ban the activities of DeFi projects in the EU territory if they do not comply with the MiCA rules. However, such a step is unlikely to make a large difference for DeFi market participants since DeFi projects do not require legal registration. Accordingly, it is impossible to determine the place of operation (in the EU or not) since all operations are virtual and are carried out over the Internet.

Certain EU regulators have voiced doubts about the authenticity of the decentralised nature of DeFi platforms, as a central development team currently operates some of them and follows standard governance guidelines in most cases (Born et al., 2022). In our opinion, in such a scenario, the owners of significant participation in DeFi projects will try to veil their significant influence on the management of the project as soon as possible. Their votes will be dispersed among many anonymous holders of management tokens.

We concur with (Capocasale & Perboli, 2022; Malkoc et al., 2021; Salami, 2021) on the need to synchronise the terms of “smart contracts” with the norms and laws on the protection of consumers' rights, which are mandatory in regulatory acts of the banking and financial industry. Standardisation of smart contracts will protect consumers' rights without diminishing the main advantages of smart contracts, such as transparency, decentralisation, immutability, elimination of intermediaries, and reduction of transaction costs.

To minimise the risks of money laundering and tax evasion, regulatory bodies should develop particular approaches to regulating financial transactions using smart contracts. First, we recommend establishing a minimum amount for transactions made through the execution of a smart contract, which will be subject to inspection by regulatory authorities, similar to financial monitoring. Verifying such transactions is possible by the smart contracts that are part of the blockchain code. Second, it is advisable to introduce requirements to businesses for the registration of smart contracts in a designated register together with the registration of transaction parties. Third, in some cases, smart contracts may require inputs from outside the DeFi ecosystem to validate the conditions specified in smart contracts. These inputs may be provided by intermediaries called "oracles" (Malkoc et al., 2021).

It is crucial to introduce responsibility for examining smart contracts used for money laundering. The registration of smart contracts can be implemented using an analog of the Ukrainian state service "Diya" (Musienko, 2023). In this case, state regulatory bodies of financial markets, mainly tax services, can analyse smart contracts for tax evasion or financial transactions. Moreover, such a service can provide a high level of automation in smart contract registration.

Of course, limitations exist in the regulatory process of crypto assets, particularly for their groups, such as NFTs and smart contracts, in decentralised finance. The fact is that no mechanism would successfully analyse those smart contracts implemented on platforms that do not require any data from clients for verification (except for an e-mail address and confirming code words). Moreover, linking smart contracts and transactions to the blockchains will improve the ability to analyse decentralised finance in the future.

The contribution to the research also derives from the contrast of hypotheses. The study's results support H1, highlighting the need for a single regulatory body to enhance the effectiveness of EU cryptocurrency regulation. We agree with respondents that the lack of a single regulatory body with the authority to regulate and control transactions with crypto assets is a significant problem for most countries. Assigning separate functions of supervision and regulation of crypto operations to non-specialised supervisory bodies reduces the effectiveness of such regulation. MiCA regulation can improve the efficacy of crypto regulation in the EU by providing a unified supervisory framework.

Regarding the second hypothesis, the findings partially support H2. While the EU-wide harmonisation suggested by MiCA can improve the effectiveness of EU cryptocurrency regulation, the results also highlight the need for further regulation to cover all groups of crypto assets, such as NFTs and DeFi, which currently need to be adequately addressed. More coherent legislation is needed. Most countries at the national level do not have legislation that covers all aspects of the crypto ecosystem. Some countries have complex and disparate regulatory rules, and different regulatory bodies have jurisdiction over crypto assets. The lack of agreed-upon rules for regulating the crypto market at the global level leads to additional risks for all crypto market participants, including the state, as the risk of using crypto assets for illegal activities increases.

The results of this study also support hypothesis H3, underlining that the precise classification of crypto assets can enhance the effectiveness of EU crypto regulation. The respondents from all surveyed countries considered the lack of a clear classification of crypto assets the main problem in crypto regulation. This is important since legal uncertainty in the interpretation of crypto assets leads not only to a slowdown in the development of the crypto market due to the cautious attitude of institutional investors but also to complex legal processes caused by the lack of unified legal norms.

Regarding H4, the findings underscore the need for rules and licensing of crypto asset operators. This research admits progress in regulating centralised cryptoexchanges and suggests considering the unique features and challenges of DeFi transactions.

The research findings partially support H5. While the results acknowledge the importance of national legislation identifying cryptocurrencies as legal tenders, they also stress the need for comprehensive EU-level regulation, such as MiCA, to guarantee efficient regulation of cryptocurrencies across borders.

The results of this study also support H6 by highlighting the role of effective EU crypto regulation in minimising the misuse of crypto assets, such as money laundering and financing terrorism. This research discusses the challenges posed by the decentralised nature of DeFi transactions and the anonymity of participants, revealing the importance of sufficient regulation to address these issues.

This research is not without its limitations. The sample of respondents was constructed based on a convenience approach. The evolving nature of DeFi and other novel FinTech technologies also restricts the pool of experts. Finally, the legislation is evolving, and it is conceivable that the respondents may not be fully aware of the developments in their countries and at the global level. We welcome further studies to test the results on a larger pool of respondents based on a random sample of national experts.

The article does not mention detailed analyses of the regulation of CBDCs and stablecoins, areas of significant interest and development within the cryptocurrency sector. This omission is premised on the focused exploration of issues regarding illicit money flows within the cryptocurrency sector. We recognise the critical importance of CBDC and stablecoin regulation, and we hope to address this gap comprehensively within our forthcoming article.

7 Concluding remarks

Our study of the current state of legal regulation for cryptocurrency assets transactions in France, the United Kingdom, Italy, Germany, and Liechtenstein analysed existing regulatory acts, highlighting that there is no unified national legal field in this area. A survey of experts on crypto assets in these countries confirmed that European legislation does not establish a consistent legal framework for effectively regulating crypto assets. Furthermore, analysis of the MiCA Regulation indicates that only three groups of crypto-assets will be covered by regulatory rules at the European Union level: exchange tokens, stablecoins and e-money tokens. However, the regulation of transactions involving security tokens, NFTs and smart contracts remains outside the scope of European legislation.

Opinions of experts in the field of cryptocurrencies gave grounds for the conclusion that an international (global) convention for regulating cryptocurrencies must be developed.

Based on an analysis of existing rules for regulating cryptocurrencies, the article concludes that these rules are based on FATF recommendations on money laundering. National regulatory acts or the results of court proceedings regarding transactions with crypto assets are primarily based on AML/KYC requirements. The MiCA Regulation is based on the rules on the disclosure of data from crypto-asset issuers and participants in the crypto-asset market.

The article proposes areas that need to be addressed by an international regulatory standard for crypto assets. Recommendations for increasing the efficiency of DeFi, NFT and smart contract regulation are provided.

Future research agendas on cryptocurrency regulation may focus on investigating the impact of regulatory rules adopted by the EU and European countries on the emerging cryptocurrency market, as well as on strengthening international cooperation, analysing the impact of regulation on market behaviour, and creating a comprehensive DeFi and NFT regulatory framework aiming to minimise illicit activities in the crypto ecosystem.

Notes

The classification of cryptocurrency in Germany is based on the interpretation of the European Union’s Markets in Financial Instruments Directive II (MiFID II), which defines financial instruments as any contract that gives rise to a cash settlement or that can be traded on a financial market.

In 2018, the Cryptoassets Taskforce (as a working group) was established in the UK and brought together the HM Treasury, the Financial Conduct Authority and the Bank of England to coordinate crypto responses.

Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on the mechanisms to be put in place by the Member States for the prevention of the use of the financial system for the purposes of money laundering or terrorist financing and repealing Directive (EU) 2015/849: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A52021PC0423.

The new MiCA regulations are expected to go into effect in 2024, following a final agreement that reached in April 2023.

The MiCA regulation extends the Financial Action Task Force’s ‘Travel Rules’ to crypto assets, requiring originators and beneficiaries of all transfers of digital funds to share identifying information. This new regulation strengthens the European anti-money laundering system, reduces fraud risks and makes transactions with cryptocurrency assets more secure.

References

Adamyk, B., & Benson, V. (2023). "DeFi Regulation in the EU: should we act now?" TRACE. https://trace-illicit-money-flows.eu/defi-regulation-in-the-eu-should-we-act-now/.

Aju, M., & Burrell, T. (2023). "Cryptoassets consumer research 2023 (Wave 4)". Financial Conduct Authority, Research Note. Available at: https://www.fca.org.uk/publication/research-notes/research-note-cryptoasset-consumer-research-2023-wave4.pdf.

AMF. (2020). "The AMF publishes an in-depth legal analysis of the application of financial regulations to security tokens". https://www.amf-france.org/en/news-publications/news-releases/amf-news-releases/amf-publishes-depth-legal-analysis-application-financial-regulations-security-tokens.

BIS. (2023). "The crypto ecosystem: key elements and risks". Bank for International Settlements, July. https://www.bis.org/publ/othp72.pdf.

BaFin. (2020). “Merkblatt: Hinweise zum Tatbestand des Kryptoverwahrgeschäfts”. https://www.bafin.de/SharedDocs/Veroeffentlichungen/DE/Merkblatt/mb_200302_kryptoverwahrgeschaeft.html.

BaFin. (2022). “Banking Act (Kreditwesengesetz - KWG)”. https://www.bafin.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/EN/Aufsichtsrecht/dl_kwg_en.pdf%3F_blob%3DpublicationFile.

Benson, V., Turksen, U., & Adamyk, B. (2023). Dark side of decentralised finance: a call for enhanced AML regulation based on use-cases of illicit activities. Journal of Financial Regulation and Compliance. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFRC-04-2023-0065

Benson, V., & Adamyk, B. (2022). "Anti-Money Laundering/Combating the Financing of Terrorism Compliance: Europe to implement more comprehensive regulation for crypto assets". TRACE. https://trace-illicit-money-flows.eu/anti-money-laundering-combating-the-financing-of-terrorism-compliance-europe-to-implement-more-comprehensive-regulation-for-cryptoassets/.

Borg, W.P.-J., Podoprikhina, G., & Bolcerek, S. (2022). "EU approves crypto assets regulation: an overview of MiCA". Lexology. https://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=3b478651-6034-4ca1-8089-8e8b9bcf34f5#:~:text=MiCA%20does%20not%20cover%20crypto

Born, A., Gschossmann, I., Hodbod, A., Lambert, C., & Pellicani, A. (2022). "Decentralised Finance—A New Unregulated Non-Bank System?" European Central Bank. https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/financial-stability/macroprudential-bulletin/focus/2022/html/ecb.mpbu202207_focus1.en.html

Capocasale, V., & Perboli, G. (2022). Standardizing smart contracts. IEEE Access, 10, 91203–91212. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3202550

Chainanalysis. (2023). "The 2023 Crypto Crime Report". Chainanlysis, February. https://www.chainalysis.com/blog/2023-crypto-crime-report-introduction

Cryptoassets Taskforce. (2018). "Cryptoassets Taskforce: final report". https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/752070/cryptoassets_taskforce_final_report_final_web.pdf

Donna, M., & Vella, F.M. (2023). "Blockchain & Cryptocurrency Laws and Regulations. Italy". Global Legal Insights. https://www.globallegalinsights.com/practice-areas/blockchain-laws-and-regulations/italy

Duggan, W. (2023). "How Does The SEC Regulate Crypto?" Forbes Advisor. June, 30. https://www.forbes.com/advisor/investing/cryptocurrency/sec-crypto-regulation/

Dupuis, D., & Gleason, K. (2020). Money laundering with cryptocurrency: Open doors and the regulatory dialectic. Journal of Financial Crime, 28(1), 60–74. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFC-06-2020-0113

Emmert, F. (2022). The regulation of cryptocurrencies in the United States of America. United States Cryptocurrency Law. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4063387

Eurofi. (2022). "Decentralised Finance (DeFi)". https://www.eurofi.net/current-topics/decentralised-finance/

Europa.eu. (2022). "EUR-Lex - 52020PC0593 - EN - EUR-Lex. Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on Markets in Crypto-assets, and Amending Directive (EU) 2019/1937". https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52020PC0593

Europarl.europa.eu. (2022a). "Markets in crypto-assets (MiCA)". Think Tank. European Parliament. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document/EPRS_BRI(2022)739221.

Europarl.europa.eu. (2022b). "Crypto assets: deal on new rules to stop illicit flows in the EU". News. European Parliament. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/press-room/20220627IPR33919/crypto-assets-deal-on-new-rules-to-stop-illicit-flows-in-the-eu.

Europol. (2021). "Cryptocurrencies – Tracing the evolution of criminal finances", Europol Spotlight Report series, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg. https://www.europol.europa.eu/cms/sites/default/files/documents/Europol%20Spotlight%20-%20Cryptocurrencies%20%20Tracing%20the%20evolution%20of%20criminal%20finances.pdf

FATF. (2023). "The FATF Recommendations". https://www.fatf-gafi.org/en/publications/Fatfrecommendations/Fatf-recommendations.html

FCA. (2019). "Cryptoassets". FCA. https://www.fca.org.uk/consumers/cryptoassets

FCA. (2022). "PS22/10: Strengthening our financial promotion rules for high-risk investments and firms approving financial promotions". https://www.fca.org.uk/publications/policy-statements/ps22-10-strengthening-our-financial-promotion-rules-high-risk-investments-firms-approving-financial-promotions

Ferreira, A., Sandner, P., & Dünser, T. (2021). Cryptocurrencies, DLT and crypto assets—The road to regulatory recognition in Europe. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3891401

Finance.ec.europa.eu. (2021). "EU context of anti-money laundering and countering the financing of terrorism". https://finance.ec.europa.eu/financial-crime/eu-context-anti-money-laundering-and-countering-financing-terrorism_en

Fletcher, E., Larkin, C., & Corbet, S. (2021). Countering money laundering and terrorist financing: A case for bitcoin regulation. Research in International Business and Finance, 56, 101387. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ribaf.2021.101387

GOV.UK. (2023). "Future financial services regulatory regime for cryptoassets". https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/future-financial-services-regulatory-regime-for-cryptoassets.

Hallak, I., & Salén, R. (2023). "Non-EU countries' regulations on crypto-assets and their potential implications for the EU", European Parliamentary Research Service, September, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2023/753930/EPRS_BRI(2023)753930_EN.pdf

Huang, S. (2021). Crypto assets regulation in the UK: An assessment of the regulatory effectiveness and consistency. Journal of Financial Regulation and Compliance, 29(3), 336–351. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFRC-06-2020-0062

Javaid, M., Haleem, A., Singh, R. P., Suman, R., & Khan, S. (2022). A review of Blockchain Technology applications for financial services. BenchCouncil Transactions on Benchmarks, Standards and Evaluations, 2(3), 100073. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tbench.2022.100073

Jotform. (2022). "How to create and analyze 5-point Likert scales". The Jotform Blog. https://www.jotform.com/blog/5-point-likert-scale/

Kafteranis, D., & Turksen, U. (2021). Art of money laundering with non-fungible tokens: A myth or reality? European Law Enforcement Research Bulletin, 22(6), 23–31.

Kakushadze, Z., & Russo, R. (2018). Blockchain: Data malls, coin economies and keyless payments. The Journal of Alternative Investments, 21(1), 8–16. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3104745

Kerrigan, C., Federis, E., & Burdzy, A. (2023). "Blockchain & Cryptocurrency Laws and Regulations. United Kingdom". https://www.globallegalinsights.com/practice-areas/blockchain-laws-and-regulations/united-kingdom

Lener, R., Furnari, S., Lorenzotti, N., & Di Ciommo, A. (2022). "The Virtual Currency Regulation Review—The Law Reviews", The Law Reviews. https://thelawreviews.co.uk/title/the-virtual-currency-regulation-review/italy.

LexisNexis (2022). "The Perfect Storm: EU's 6th Anti-Money Laundering Directive Raises Regulatory Risk with a Broader Definition of Money Laundering & Extended Criminal Liability". https://www.lexisnexis.com/blogs/gb/b/compliance-risk-due-diligence/posts/the-perfect-storm-eu-s-6th-anti-money-laundering-directive-raises-regulatory-risk-with-a-broader-definition-of-money-laundering-extended-criminal-liability.

Luxembourg, D. (2022). "EU strikes a deal on 'travel rule' for crypto-asset transfers". Deloitte Luxembourg. News. https://www2.deloitte.com/lu/en/pages/financial-services/articles/europe-strikes-deal-travel-rule-crypto-asset-transfers.html

Malkoc, E. S., Badak, Z., & Guvenc, S. N. (2021). Evaluation of certain problems that may arise with smart contracts from a legal perspective. Academia Procedia, 14(1), 20–22. https://doi.org/10.17261/Pressacademia.2021.1479

MiFIR. (2014). "Regulation (EU) No 600/2014 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 15 May 2014 on markets in financial instruments and amending Regulation (EU) No 648/2012". European Securities and Markets Authority. https://www.esma.europa.eu/publications-and-data/interactive-single-rulebook/mifir

Money Gate. (2023). "Crypto regulation and laws around the world in 2023". https://money-gate.com/crypto-regulation-and-laws-around-the-world/

Morton, D. (2020). The future of cryptocurrency: An unregulated instrument in an increasingly regulated global economy. Loyola University Chicago International Law Review, 16(1), 129–143.

Moyle, A., McDermott, C., & Balendran, A. (2022). "The Law Commission of England and Wales Proposes to Classify NFTs as Data Objects". Global Fintech & Digital Assets Blog. https://www.fintechanddigitalassets.com/2022/11/the-law-commission-of-england-and-wales-proposes-to-classify-nfts-as-data-objects/

Musienko, Y. (2023). "How to develop electronic document service like Ukrainian Diia/Diya?" Merehead. https://merehead.com/blog/electronic-document-service-like-diya/

Nolasco, C., & Vaughn, M. (2021). Convenience theory of cryptocurrency crime: A content analysis of Us Federal Court Decisions. Deviant Behavior, 42(8), 958–978. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639625.2019.1706706

Nägele, T. (2020). "Liechtensteins Tokens and T.T. Service Providers Law". Medium. https://tokencontainermodel.com/liechtensteins-tokens-and-tt-service-providers-law-b23574d595f9

O'Roker, W., & Lourimi, A. (2023). "Blockchain & Cryptocurrency Laws and Regulations. France". Global Legal Insights. https://www.globallegalinsights.com/practice-areas/blockchain-laws-and-regulations/france

PwC. (2023). "PwC Global Crypto Regulation Report 2023". https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/new-ventures/cryptocurrency-assets/pwc-global-crypto-regulation-report-2023.pdf

Salami, I. (2021). Challenges and approaches to regulating decentralised finance. American Journal of International Law Unbound, 115, 425–429. https://doi.org/10.1017/aju.2021.66

Sandner, P. G., Ferreira, A., & Dunser, T. (2022). Crypto Regulation and the case for Europe. In D. A. Tran, M. T. Thai, & B. Krishnamachari (Eds.), Handbook on Blockchain (pp. 661–693). Springer.

Shinde, M. (2022). "Envisaging Global Regulations on Cryptocurrency". papers.ssrn.com. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4316798

Singh, J. (2020). "An overview of the Liechtenstein Blockchain Act". Cointelegraph. https://cointelegraph.com/learn/an-overview-of-the-liechtenstein-blockchain-act

Van der Linden, T., & Shirazi, T. (2023). Markets in crypto-assets regulation: Does it provide legal certainty and increase adoption of crypto-assets? Financial Innovation. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40854-022-00432-8

Skirka, A., Adamyk, B., Adamyk, O., & Valytska, M. (2020). Trust in the European Central Bank: Using data science and predictive machine learning algorithms. ACIT-2020. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACIT49673.2020.9208857

Stamm, H., & Meinert, M. (2022). "German regulatory framework for market participants in crypto assets. https://www.aima.org/article/german-regulatory-framework-for-market-participants-in-crypto-assets.html

Winnowicz, K., Au, C.-D., & Stein, D. (2022). "Regulation of Cryptocurrencies in the European Union – Impact of European regulatory notifications on the cryptocurrency market". In 4th International Conference on Applied Research in Business, Management and Economics. Prague, Czech Republic. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/359391758

Zetzsche, D. A., Arner, D. W., & Buckley, R. P. (2020). Decentralized finance. Journal of Financial Regulation, 6(2), 172–203. https://doi.org/10.1093/jfr/fjaa010

Funding

Research for this paper received funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 Programme under Grant Agreement 101022004 – TRACE Project – https://trace-illicit-money-flows.eu.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors made substantial contributions to the conception of the work; drafted the work and revised it critically for important intellectual content; approved the version to be published; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare relevant to this article's content.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Questionary: "cryptocurrency regulation in europe: expert perspectives"

Appendix 2: Proposals regarding the architecture of the international convention for the regulation of crypto assets

Type of proposal | Explanations | |

|---|---|---|

Recognition of means of payment | Recognising exchange tokens as a means of payment and exchange can be made by analogy to cash functions. The same rules to exchange tokens as for cash and noncash transactions regulation can be applied | |

Procedure for issuing crypto assets | Publication of a special document (prospectus) | The emission document's publication aims to disclose information about the issuer and tokens |

Obtaining permission from the regulatory authority | Obtaining permission from a particular body regulating the crypto asset market to issue tokens | |

The procedure for financial promotion | A set of rules for advertising to attract investors to invest in tokens or projects related to developing crypto assets should be unified | |

Risk management procedure | Risks associated with money laundering | Risk management in crypto assets related to money laundering is fully described in the FATF recommendations. They should be implemented internationally to regulate crypto assets |

Investment risks | The MiCA Regulation provides financial requirements for token issuers and the formation of reserves that can partially cover such risks. After the adoption of MiCA, only financially capable companies can issue tokens associated with assets (stablecoins). The risks of other types of coins need clarification | |

Liquidity risks | ||

Responsibility of crypto asset market participants | The nature of the liability of crypto asset market participants can be divided into two groups: (1) the liability of issuers for nonreceipt of permits for issuing and the lack of registration with the competent regulatory authority; (2) liability for money laundering with cryptocurrencies. It is advisable to establish the amount of liability under the FATF recommendations for money laundering and under the sanctions of national regulatory authorities of financial markets applicable to unregistered participants | |

Requirements for national legislation | It is advisable to build national legislation on the principle of codification, where all the norms of regulation of the crypto asset market will be collected in one law, and one section of the law will be allocated to each crypto asset. More detailed regulatory norms can be outlined in a special instruction of the regulatory authority. This approach will make it possible to combine parts of existing regulations devoted to regulating cryptocurrencies in one law and ensure the clarity of regulation for all participants in the crypto asset market | |

Requirements for national regulatory authorities | As in the case of a single law regulating the crypto asset market, it is advisable to create or provide crypto asset regulatory functions to an existing body. Such a body can be built on the example of a macroprudential regulator. The existence of a single body for regulating and supervising the crypto asset market will avoid duplication of functions and powers | |

Requirements for the national system of statistics of the crypto asset market | The formation of a national system of statistics for the crypto asset market is essential for the regulation and supervision of the functioning of the market. Exchange tokens, e-money tokens and stablecoins should be included in the state's money supply. It will effectively assess the money supply and risks of money circulation, which will correct the monetary policy signals | |

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Benson, V., Adamyk, B., Chinnaswamy, A. et al. Harmonising cryptocurrency regulation in Europe: opportunities for preventing illicit transactions. Eur J Law Econ 57, 37–61 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10657-024-09797-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10657-024-09797-w