Abstract

By combining approaches from the economic theory of crime and of industrial organization, this paper analyzes optimal enforcement for three different forms of corporate misconduct that harm competition. The analysis shows why corporate crime is more harmful in large markets, why governments have a disinclination to sanction firms whose crime materializes abroad, and why leniency for those who self-report their crime is a complement, and not a substitute, to independent investigation and enforcement. As public authorities rely increasingly on self-reporting by companies to detect cartels, the number of leniency applications is likely to decline, and this is borne out by data. Upon a review of 50 cases of corporate liability from five European countries, competition law enforcement, governed by a unified legal regime, is more efficient than enforcement in bribery and money laundering cases, governed by disparate criminal law regimes. Sanction predictability and transparency are higher when governments cooperate closely with each other in law enforcement, when there are elements of supra-national authority, and when the offense is regulated by a separate legal instrument. Given our results, Europe would benefit from stronger supra-national cooperation in regulation and enforcement of transnational corporate crime, especially for the sake of deterrent penalties against crime committed abroad.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Since the turn of the millennium, governments have sharpened regulations regarding corporate misconduct, including bribery, money laundering, and violations of competition law.Footnote 1 At the same time, enforcement systems of corporate liability and sanctioning have become more flexible as a result of a generalization of settlement-based procedures. Since governments are not open about how they rank the many objectives behind the regulation of corporate misconduct, enforcement outcomes are at risk of being exposed to influence from non-legal factors, such as the firm’s market position or whether the crime was committed domestically or abroad. This article investigates trade-offs between enforcement strategies, focusing in particular on the difficulty of imposing sanctions that deter corporate crime while at the same time avoiding harmful domestic market consequences. We have found no proper investigation of this trade-off in the literature. By combining the insights from the economics of crime and theories of industrial organization, we are able to analyze its consequences for different forms of profit-motivated corporate crimes and their persistence in a market context. For this analysis we assume that a government’s incentives to control corporate crime depends on how it values corporate profits, taking the harmful consequences of the crime into account.Footnote 2 Intuitively, this net benefit depends on the geographic distribution of both criminal profits and harmful consequences for consumers. When the consequences materialize domestically, the government’s effort to control crime depends on how much it values the interests of consumers versus those of producers – that is, on the extent of benevolence. Benevolent governments will aim to control corporate crime and will prioritize circumstances where the risk of market concentration is high. They will also prioritize large markets, where the consequences of misconduct are more serious. Indeed the analysis shows that (a) corporate crimes are more damaging in markets of large size. When the consequences play out abroad, a government (benevolent or not) has few incentives to control the crime.Footnote 3 Providing an immediate advantage to home-country consumers, employers, voters, and taxpayers will likely outweigh the longer-term benefit associated with integrity in international markets.Footnote 4 We hence predict that (b) corporate offenses whose consequences materialize in another country will be tacitly condoned by elected officials, and to the extent that these offenses are investigated and charged at all, we predict that enforcement actions will lead to mild sanctions. This (international) free-riding problem, which implies inconsistency of sanction practice, calls for stronger barriers to prevent political interference in law enforcement. In such circumstances, efficient enforcement depends on international cooperation, and supra-national enforcement may be more efficient than enforcement at the national level.

In practice, optimal enforcement is challenged by the fact that governments are unable to impose penalties high enough to deter the most profitable forms of crime. However, they always have an opportunity to encourage offenders to cooperate with enforcement agencies by offering a predictable and substantial penalty reduction for corporations that self-report their offenses. We show that (c) it is easier for enforcement systems to uncover crime through leniency programs than to impose sanctions that will effectively deter the acts.

Our model opens the black box of corporate incentives to monitor its own involvement in crime. Usually, firms are assumed to be a unitary entity, so when a crime occurs, it happens at the instigation of its management, which is equated with “the firm.” The reality is more complex. Corporate crimes are committed by individuals within firms. Not all employees are involved, and corporate management will not always know. In some firms, profit-motivated crime is tacitly condoned by company officials, implicitly, encouraged by their management practices,Footnote 5 while in other firms, there is no tolerance to crime. We explore what aspects of public policies may motivate business owners and executives to implement safeguards against corporate crime. When it comes to the structuring of sanctions and liabilities for the sake of inducing corporations to invest in crime-preventive systems and monitor their operations, we show why such ambitions will often fail, even if many policy reports and corporate statements argue to the contrary. In terms of law enforcement, it is impossible to induce firms to adequately monitor their own business practice unless there is a risk of detection by a government agency and an ensuing sanction. Firms’ investment in monitoring for crime detection depends on government enforcement (i.e., they are strategic complement), and therefore, for governments, leniency for self-reporting is a complement to self-initiated investigation and not a substitute for it. As a consequence (d) the number of cases uncovered through leniency programs increases with the authorities’ efforts placed in monitoring and enforcement (independent of firms’ self-reporting).Footnote 6 Finally, law enforcement, if organized for optimal crime detection, may have a negative effect on competition in concentrated markets, and therefore, even benevolent governments face a difficult trade-off and may seek to shield certain firms from heavy sanctions. This is especially true when highly asymmetric penalties are imposed in collusion cases in terms of leniency offered to firms which cooperate first with the authorities. The competitive advantage they win might lead to an increase in sector concentration. Accordingly, (e) the reliance on leniency in competition cases, including highly asymmetric sanctions, may have a potentially perverse effect on competition.

Assuming that consequences of crime ought to matter for governments’ enforcement priorities (Rose-Ackerman & Palifka, 2016), the theoretical approach provides a benchmark for evaluating law enforcement systems and practices. With an emphasis on European countries, we investigate the extent to which governments are able to secure enforcement of corporate liability in line with the incentives delineated by our analysis. Internationally, the United States stands out as the most active enforcer of corporate liability, including when it comes to cross-border offences, and many countries learn from its approaches. By contrast, there is less information available about enforcement of corporate liability in Europe. This paper contributes to fill that gap. The questions discussed in the theoretical section are explored based on an analysis of a sample of 50 enforcement cases from five different (European) jurisdictions collected for this study. They reveal that, compared to the United States, European enforcement of corporate liability is more heterogeneous across countries. It is also opaque because the information necessary to conduct thorough empirical studies of enforcement practices is not easily available. The information we have been able to gather shows that criminal law enforcement systems perform inadequately assessed against recommendations presented in the theory section. In particular, most enforcement regimes (save for competition law) have a low score with regard to predictability. The review of cases also confirms some of the predictions made in the theoretical sections, in particular regarding the impact of the geographical location of the crime on the sanction level. Moreover, our study of the relationship between the imposition of fines in concentrated markets and later merger cases suggests that heavy fining in concentrated markets may provoke mergers below the threshold for intervention under merger control rules, indirectly causing harm to consumers.

The rest of the article proceeds as follows. Section 2 describes the regulation of corporate liability and points to relevant results in the literature on law and economics. Section 3 presents an economic model for analysis of the above-mentioned trade-offs. First, we describe a general model of corporate crime in a market context, illustrated with an example of collusion. Second, we investigate governments’ incentives to control corporate crime in view of how they value producer surplus relative to consumer surplus.Footnote 7 Third, we explore optimal sanctions, and especially the use of leniency programs when Becker-style deterrence is not an option. In Sect. 4 we turn to enforcement in practice. By reviewing practices in Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, and the United Kingdom, we check whether current enforcement practices in Europe are consistent with the theoretical results. We discuss policy implications and conclude in Sect. 5.

2 Regulation of corporate liability

Governments regulate and sanction corporate misconduct in different ways (Pieth & Ivory, 2011). With the expansion of corporate regulations in the 20th century, it became possible across the United States and Western Europe to hold firms criminally responsible for economic crime committed by their employees. The basis for enforcement was vicarious liability combined with some form of evaluation of responsibility (Oded, 2013). Most countries criminalized corporate bribery in the late 1990 s upon the implementation of international conventions such as the United Nations Convention against Corruption, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Anti-Bribery Convention, and the Council of Europe’s Civil Law and Criminal Law Conventions on Corruption.Footnote 8 Criminalization of failure to comply with anti-money-laundering regulations (as stipulated by the US Bank Secrecy Act of 1970) started with the US Money Laundering Control Act of 1986; thereafter, other OECD countries followed suit with a largely harmonized combination of criminal and non-criminal regulations, coordinated through the Financial Action Task Force (FATF).Footnote 9 Competition in markets is regulated primarily as a non-criminal matter.Footnote 10 Today, as a result of EU-cooperation, such regulations are largely harmonized across Europe and is substantially consistent with the even older regulations in the United States.Footnote 11

Normally, criminalization is associated with stricter penalties, a risk of imprisonment for the involved individuals, and compensation for victims. For corporate offenders, it may be followed by indirect consequences such as damages to be settled with business partners, debarment from public procurement, exclusion from some investment funds, and reputational costs. For enforcement agencies, criminalization implies a higher burden of proof, which in many cases means de facto protection against penalties for the offender, especially for individuals who act on behalf of an organization.Footnote 12 In practice, however, the distinction between criminal and non-criminal enforcement matters less than one might suppose. The regulatory development has gone in the direction of functional equivalence. In other words, corporations can be sanctioned in similar ways, regardless of how the jurisdiction in question combines criminal and non-criminal enforcement (Pieth et al., 2014: 37–40).

The regulatory regimes for corporate liability have evolved in other ways, too, since the turn of the millennium. Around that time, governments started to recognize the shortcomings in enforcement vis-à-vis corporate offenders, who could easily hide their crimes behind international corporate structures and financial secrecy provisions. Too strict vicarious liability would only serve to strengthen firms’ incentives to hide whatever crime they might have conducted, governments realized, and thus such attempts to secure deterrence could harm markets more than it protected them (Arlen, 1994; Khanna, 2000). Today, countries enforce corporate liability with some sort of evaluation of negligence, if not an assessment of guilt (OECD, 2016). This allows enforcement agencies to consider the reasonableness of the penalty in view of the corporation’s actual responsibility for misconduct (Hjelmeng & Søreide, 2017; Miller, 2018). While the weight of these circumstances is indeed a question addressed by courts, court assessment of the material facts is costly in complex cases of corporate wrongdoing. It is also a time-consuming process, and society will often be better off if corporate defendants can go on with their business as long as they do so with stronger internal measures against corporate crime. This aim, governments realize, can be secured if corporate offenders can be “rewarded” with a lower penalty if they have in place proper crime prevention systems, self-report their offences, and cooperate with law enforcers. Across countries, such a leniency strategy for self-reporting is especially well-developed within the field of antitrust/competition law (Borrell et al., 2014; Wils, 2007), while it might make sense to adapt the strategy for other forms of corporate misconduct too (Arlen, 2020; Bigoni et al., 2015).

Given the widespread adoption of leniency programs by antitrust authorities to combat collusion in markets, economists have conducted extensive research to assess them (see Spagnolo, 2008 and Marvao & Spagnolo, 2018 for a literature review). The overall conclusion of such research is that leniency programs tend to make collusion more difficult. However, researchers also show that there are circumstances in which a leniency programs can facilitate collusion and cartel stability. Buccirossi and Spagnolo (2006) show in a static model that leniency may provide an effective mechanism for occasional sequential illegal transactions that otherwise would not be feasible. Harrington and Chang (2015) show in an infinite horizon model that while a leniency program reduces the duration of cartels in industries where collusion is least stable, it may lengthen the duration of cartels in industries where collusion is easier to sustain. The reason, they explain, is that optimal non-leniency enforcement becomes weaker in these markets due to the limited resources of antitrust authorities. In our study we come to a similar conclusion, which confirms this concern, but the causation channel is different.Footnote 13 Together with the results of Harrington and Chang (2015), our findings highlight the importance of enforcement actions that are not prompted by leniency applications.

Governments increasingly allow their law enforcers and corporate offenders to end cases with a non-trial resolution, that is, a negotiated settlement that opens for a discretionary evaluation of corporate offenders’ compliance system and cooperation with law enforcement (Garrett, 2014; OECD, 2019). Governments defend the practice as a way to align two aims, that of promoting corporate compliance and that of deterring crime (Ivory & Søreide, 2020). Unless the conditions for such enforcement are clearer than what we see today, and the benchmark sanctions higher, there is a high risk that governments will achieve neither of these objectives (Garrett, 2014). For the sake of regulatory efficiency, some governments have started to describe what sort of compliance systems firms ought to have in place to merit lenient treatment under non-trial resolutions.Footnote 14 Yet there is substantial uncertainty with respect to current regimes, and the level of informality in these processes is generally high. Settlement-based enforcement normally comes with broad discretion for prosecutors, limited transparency for the public, weak protection against double jeopardy, and criminal sanctions below the level of appropriate crime deterrence.Footnote 15

Governments’ ambition to structure sanctions in a way that both promotes corporate compliance and deters crime is largely inspired by economic research on corporate crime (Shavell, 2004, Ch 9 and 10). Enforcement may prevent crime if strict liability with severe sanctions is combined with predictable penalty reductions for certain corporate behaviors (Arlen & Kraakman, 1997; Buccirossi & Spagnolo, 2006; Bigoni et al., 2015; Landeo & Spier, 2020). With respect to sanctions, economists typically consider the total impact of consequences, regardless of legal category (criminal or non-criminal), and take into account both direct and indirect consequences of the penalty, including those beyond the control of enforcement agencies. The crime-deterring impact of enforcement hinges on a sufficiently broad definition of liability, a real risk of crime detection, the predictability of a penalty, and multiple consequences for employees (Arlen, 2020; Polinsky & Shavell, 2000). These criteria apply to settlement-based enforcement as well, yet the added flexibility weakens deterrence if offenders believe they can negotiate themselves out of a serious penalty. It also distorts justice if the difference between the offered sanction and the expected trial result becomes too large for alleged offenders to ever refuse an offered settlement and opt instead for court proceedings (Søreide & Vagle, 2022).

We know less about how enforcement of corporate liability ought to take into account factors such as the perpetrators’ market situation, the nature of the crime, and political priorities. A lack of clarity regarding enforcement practices and sanction principles suggests that the barriers against undue influence on enforcement outcomes might be too weak. We need to understand why such influence might happen in relation to different forms of crime, the consequences for markets, and the consequences for optimal regulation. The next section presents a theoretical analysis of these concerns.

3 Theoretical analysis

We concentrate on an economic sector with \(N\ge 2\) active firms producing a normal good with constant marginal cost c. Assuming these firms produce collectively a quantity Q(N), the net consumer surplus is denoted \( S(N)=\int _0^{Q(N)}P(x) dx - P(Q(N))Q(N)\). Let \(q_i\) denote the production by firm i and \(Q_{_{N-i}}=Q(N)-q_i\). The firm’s \(i=1,\ldots ,N\) profit is denoted \(\pi _i(q_i,Q_{_{N-i}})\) and the sector total variable profit \(\pi (N) = \sum _{i=1}^{N}\pi _i\left( q_i,Q_{_{N-i}}\right) = P(Q(N))Q(N) - c Q(N)\). The utilitarian government aims to maximize the objective function:Footnote 16

where \(\lambda \ge 1\) is the weight the government puts on firms’ profit compared to net consumer surplus. This weight can reflect macroeconomic concerns, such as employment and taxation, that tilt political objectives toward the industry. More disturbingly, it can be the result of capture by the industry in question. An uncaptured government might set \(\lambda =1\) so as to maximize the net surplus from trade. We analyse the trade-off and coordination problems governments face in controlling corporate crimes (i.e., crimes that benefit a firm by increasing its profits) and the impact of the tools they have at hand.

We are interested in national governments’ incentives to control corporate crimes that increase artificially the rents of the firms by stalling competition such as collusion to share markets, money laundering or corporate bribery for procurement contracts.Footnote 17 The social “loss” function of stalling competition is:

where \(\Delta \pi (N)= \pi (1) -\pi (N)>0\) is the increase in the total profit of the sector when the firms behave like a monopolist. The consumers/users suffer a loss equals to \(S(N) -S(1) \), which is larger than the industry extra-profits. It is indeed easy to see that if \(\lambda =1\) then the loss is positive: \(L(N) = \int _{Q(1)}^{Q(N)}P(x) dx -c\big (Q(N)-Q(1)\big )> \big (P(Q(N))-c\big )\big (Q(N)-Q(1)\big )>0. \) Moreover, as long as Q(N) is increasing and concave in N, the loss is also increasing and concave in N.Footnote 18 To provide the micro foundations for the loss function L(N), we consider a simple model of collusion. However, the results presented in Sects. 3.2 and 3.3 are quite general, and do not depend on the specifics of this illustrative example.

3.1 An illustrative example: collusion in markets

We focus on the possibility that firms might collude to raise price and industry profit. To ease the exposition we consider a linear demand, \(Q=a-p\), and \(N> 2\) symmetric firms competing in Cournot fashion. In equilibrium each firm produces a quantity \(q={a-c\over N+1}\) so that the total production in the absence of collusion is \(Q(N)=(a-c) {N\over N+1}\). “Appendix” shows that the loss from collusion is:

It can now be confirmed that \( L(N)>0\) if and only if \(\lambda < {3N+1\over 2(N- 1)}\), which implies that the loss is always positive if \(\lambda \le {3\over 2}\). Moreover L(N) increases with N iff \(\lambda \le {N\over N- 1}\) and is concave in N iff \(\lambda \le {2N-1\over 2(N-2)}\). It is, for instance, concave when \(\lambda =1\). In other words if the government values consumer surplus enough (e.g., as much as it values corporate rents), the social loss of collusion is positive, increasing and concave with N. Finally, the harm caused by collusion in (3) increases with the total market size, \(Q^*=a-c\). Collusion in a small market is less socially damaging than collusion in a large one. The “Appendix” presents two other simple models, one of bribery and the other of violation of AML regulations, that yield similarly shaped loss functions.

3.2 National government incentives to fight corporate crime

We now examine a government’s incentives to implement prevention measures and sanction mechanisms, if any, to prevent corporate crime. For this discussion we assume a benevolent government that aims to maximize net national surplus. We distinguish between two sets of circumstances, one in which the crimes in question are confined nationally, in Sect. 3.2.1, and another, in which the crimes generate negative international externalities, in Sect. 3.2.2.

3.2.1 Social loss of domestic corporate crimes

When a corporate crime is committed domestically, without generating international externalities, a benevolent government will fully internalize it. Since it is not captured by firms potentially involved in the misconduct, a scenario reached by setting \(\lambda =1\), a benevolent government maximizes net consumer surplus. Its incentive to fight corporate crime is then proportional to the national social loss that the crimes are expected to generate, \(\tau (N)L(N)\) where \(\tau (N)\) is the probability that a crime occurs undetected.

On the one hand, the preceding analysis reveals that the loss L(N) increases in N when \(\lambda =1\). Stalling competition is more damaging for consumers when markets are not concentrated. In very concentrated markets, firms have market power anyway, and even when their prices are regulated, they enjoy some rents. So when they stall competition, collude or make corrupt deals, the loss for consumers is, all else being equal, smaller. On the other hand, these crimes are more likely to occur in concentrated markets than in more competitive ones. This is especially true of collusion, where coordination and enforcement become more difficult as the number of conspirators increases.Footnote 19 If offences are carried out more easily under circumstances of few competitors, it means that in general \(\tau (N)\) should be decreasing in N. Therefore the net effect of an increase in N on the expected social loss is ambiguous. In what follows we show how these conflicting forces interact.

Proposition 1

Let \(\lambda =1\). Assume that \(\tau (N)\in [0,1]\), the probability that the corporate crime goes undetected, is strictly decreasing and log-concave in \(N\ge 1\) with \(\tau (1)>0\) and \(\lim _{N\rightarrow +\infty } \tau (N)=0\). The expected social loss from corporate crime, \(\tau (N)L(N)\), is increasing for \(N\le N^*\) and decreasing for \(N>N^*\), where \(N^{*}>1\) is so that

Proof

See “Appendix” \(\square \)

The examples of losses defined in (3) (but also in (14), and (16) in “Appendix”) are log-concave. In fact they are concave when \(\lambda =1\), which is stronger than log-concave. Now if the probability of the crime going undetected \(\tau (N)\) is also log-concave, then the expected social loss from corporate crime, \(\tau (N)L(N)\), is first increasing and then decreasing, and therefore reaches a maximum for some finite value of \(N>1\).

To keep the exposition simple, this analysis abstracts from the complexity of how criminals interact and sustain their illegal deals, so that \(\tau (N)\) is a black box. Here, we provide a discussion of the microfoundations of the function and how it can be endogenized.Footnote 20 This function will generally depend on the specificity of the crime and the market being studied. For instance, if a public procurement corruption deal or a money laundering case involves a firm while excluding its N competitors (see “Appendix”), the firms excluded from the illegal agreement may learn about it and complain. If there is a chance \(p\in (0,1)\) that each firm excluded from the corrupt deal becomes a whistle-blower, then \(\tau (N)= (1-p)^N=exp\big (N log(1-p)\big )\), which is decreasing, log-concave. More generally, all functions such that \(\tau (N)= exp(-\rho N)\) with \(\rho > 0\) are log-concave, and the result of proposition 1 holds.Footnote 21

Another example concerns collusion in markets. Since it involves \(N>1\) firms, collusion raises a coordination problem. Each firm has an incentive to deviate from the collusive agreement to maximize short term profit. So in a static context collusion unravels, unless the cartel uses other means to enforce its illegal agreement, such as violence or blackmailing (Buccirossi & Spagnolo, 2006). The illustrative example in Sect. 3.1 can easily be extended to address the commitment problem. We assume that the game is repeated ad infinitum and that the firms’ discount factor is \(\delta \in [0,1]\). Firms play a “grim-trigger” strategy of playing the collusive output until one firm deviates, then keep to the competitive strategy forever after that. The “Appendix” shows that in a stationary environment without any randomness, collusion is an equilibrium if \(\delta \) is sufficiently large (i.e. if firms are patient and place sufficient value on future profits):

To account for randomness in markets, we assume that in each period there is a shock \(\epsilon ^t\) IID across period with 0 mean and distribution function \(F(\delta )\) so that collusion breaks down if \(\delta \le \frac{(N+1)^2}{(N+1)^2+4N} -\epsilon ^t\). The RHS of Eq. (5) being increasing in \(N>1\), sustaining collusion is harder when N is large: collusion unravels with probability \(F\left( \frac{(N+1)^2}{(N+1)^2+4N}-\delta \right) \). With a uniform distribution on \([-\delta ,\delta ]\) with \(\delta \ge 0.5\), \(\tau (N)= 1 -\frac{(N+1)^2}{(N+1)^2+4N} \frac{1}{2\delta } \), which is decreasing and concave in N.Footnote 22

In other words, under general assumptions, the expected social loss from corporate crime, \(\tau (N)L(N)\), reaches its maximum for some value \(N^*> 1\). Moreover, it increases with \(Q^*\), the size of the market, since L(N) increases with the market size. A benevolent government that wishes to control domestic corporate crime ideally should tailor its efforts to the specific sector under consideration. In particular, enforcement agencies should give priority to oligopolistic sectors, where the market concentration is relatively high, where collusion and corruption are real threats, and where the market size is large enough for anti-competitive practices to substantially harm consumers/taxpayers. This implies that governments need sanctions guidelines that allow law enforcers to take the market situation into account in cases of corporate crime. This pragmatic case-by-case approach seems optimal when the government is benevolent, but should not come with the cost of reduced sanction predictability.

3.2.2 International externalities of corporate crime and domestic profit

Now we turn to corporate crime that generate negative externalities in foreign countries – collusion to share international markets, violation of anti-money laundering regulations and bribery conducted to win public contracts abroad being different cases in point. When negative externalities occur outside a country, while the extra criminal profits reaped by corporate offenders increase the country’s gross domestic product, a benevolent government will have very few incentives to control the problem. From this country’s perspective, there is only a fiscal cost to be paid in this effort for international integrity, and no direct benefit to be reaped - at least not in the short run.Footnote 23 Unless there is strong international solidarity in society, punishing these firms harshly for their crime is unlikely to be popular among voters, who are both employees and taxpayers. In this case the government will favor domestic firms’ rent over foreign consumer surplus. We establish easily the following proposition.

Proposition 2

If \(\lambda \), the weight the government puts on the corporate sector rent, is larger than \({\tilde{\lambda }} = {S(N)-S(1)\over \Delta \pi (N)}> 1\) then the “loss” (2) from corporate crimes is a gain: \(L(N) <0\).Footnote 24

Proposition 2 implies that if the crime occurs in another country without creating much distortions on the domestic market, a government under political pressure, such as an upcoming election, will put a very small weight (i.e., close to 0) on the interests of foreign consumers/taxpayers, or alternatively, a very large (i.e., infinite) weight \(\lambda \) on domestic firms’ profits so that the “loss” (2) from corporate crimes is a gain: \(\lim _{\lambda \rightarrow +\infty }{\big (\tau (N) L(N)/ \lambda }\big )= -\tau (N) \Delta \pi (N)<0. \) It generates new taxes and employment at home, while the harm (to taxpayers or consumers) is abroad. Committing resources to investigate and sanction the extraterritorial criminal behavior will easily be perceived as a cost to domestic producers and taxpayers, while benefiting primarily foreign societies and competitors. Unless there is strong international solidarity in society, punishing these firms harshly is unlikely to be popular among voters, who are both employees and taxpayers. We therefore predict lax enforcement of punishment for corporate crimes that hurt consumers and taxpayers in a foreign country.

In the enforcement of antitrust law, the US and the EU, as well as most other jurisdictions, base their competence on the so-called “effects doctrine”, although the respective interpretation varies. This basically means that conduct or cooperation in question may be targeted by the competition authorities provided that it produces effects at the territory within jurisdiction, regardless of whether the infringement took place outside that territory.Footnote 25 However, if the infringement takes place within the jurisdiction but produces effects only in third countries (e.g., export cartels) the antitrust rules will not apply extra-territorially.Footnote 26 In other words, in matters of antitrust the result of proposition 2 is a principle of law.

This is a typical free-riding problem insofar as the loss is spread across several jurisdictions while the benefit accrues to one country. Accordingly, unless there is a coordinated international intervention to control such international corporate crimes with economic sanctions large enough to make it socially unprofitable for the country benefiting from them, the problem is likely to continue unabated. As illustrated by the “effects doctrine” in antitrust law, or by the tense discussions around taxation of multinationals and remedies to curb their fiscal “optimization” practices, the difficulty lies in the intergovernmental process toward coordinated international action.

Nonetheless, large economies, such as the European Union (EU) and the United States, are in position to unilaterally impose sanctions that are big enough to curb the incentives of countries benefiting from the crimes. They can induce other countries to internalize the negative externalities they generate when they condone certain forms of crime that benefit themselves at the expense of other societies. The United States is in a stronger position than most to issue threats to other countries and impose sanctions on international corporations. They have for instance forced Switzerland to enhance financial transparency and cooperate in investigation of tax matters (see Church, 2016). Similarly, the EU’s listing of non-cooperative tax jurisdictions has triggered changes in countries known to offer financial secrecy and has contribute to promote fairer taxation.Footnote 27 In the European Union, the existence of supra-national authorities such as antitrust bodies help also coordinate sanctions against those crimes that harm any EU members.

3.3 Deterrence of crime through optimal sanctions: leniency programs and precautionary measures

The goal of this section is to analyze what a benevolent (i.e., uncaptured) public authority should do to combat corporate crime. This provides us with a model of optimal enforcement and a benchmark against which to compare actual practices and sanctions. We focus on domestic crimes which a benevolent government has an incentive to control (i.e., \(\lambda =1\)). We examine the optimal structure of the sanctions that the government should inflict on firms to curb them. The government set a sanction scheme that apply to all firms. For legal equity concerns it cannot ex-ante favor one firm over the other.Footnote 28 Since the N firms are symmetric, it implies that in equilibrium they react to the government incentives in the same way. To ease on notation we therefore drop the firm’s index when computing its reaction to the sanction scheme in Sect. 3.3.1.

3.3.1 Self-reporting and deterrence

Compared to a law enforcement agency, corporate management is far better positioned to monitor crime committed by its firm’s employees or other representatives. The firm has two types of tools available for the monitoring of crime committed by employees. First, it can invest ex-ante \(K\ge 0 \) in preventive measures that will make the detection of crime easier for all parties (e.g., double-checking/endorsing of sensitive information and clearance procedures, digitization to safeguard all actions and corporate information exchanges, software to perform monitoring in real time, procedures to facilitate whistleblowing, etc.). Second, the firm can invest \(m\ge 0 \) to monitor employees on a daily basis. The probability that the firm will discover crime when committed, \(p^{f}(m/K)\in [0,1]\), is increasing and concave in \(m\ge 0\) for all \(K\ge 0\). We assume that precautionary measures ease the monitoring of crimes \(p^{f}(m/K_{1})>p^{f}(m/K_{2})\) when \(K_{1}>K_{2}\ge 0\) and \(m>0\). Finally, \(p^{f}(0/K)=0\) for all \(K\ge 0\). In other words, the firm must invest in some monitoring if it aims to detect corporate crime.

The government too can detect corporate crime, but is less efficient than the firm in this task because it is external to the firm’s operations. Let \(p^{g}(m/K)\in [0,1]\) be the probability that the government finds out that a corporate crime has been committed when such a crime has in fact occurred. We have \(p^{g}(m/K)\le p^{f}(m/K)\), \(\forall m>0\). As for the firm, preventive actions make crime detection easier: \(p^{g}(m/K_{1})>p^{g}(m/K_{2})\) when \(K_{1}>K_{2}\ge 0\) and \(m>0\).

Taking the perspective of the representative firm, we focus on its gain/loss from reporting corporate crime. Let \(F>0\) be the base fine – that is, the fine in cases where the firm did not report the crime while there is also no evidence that it tried to cover it up. Let \(F^{h}\ge 0\) be the fine in cases where there is evidence that the firm detected the crime and hid it. Finally, let \(F^{r}\ge 0\) be the fine in cases where the firm reported the crime to the authorities. This implies that if a corporate crime is committed, and \(\beta \in [{1\over N},1]\) is the firm’s fraction of the rent, then the firm’s expected profit is (see “Appendix”):

where \( \mathbbm {1}_{\{r\}}\) equals 1 if the firm reports the crime and 0 if it does not, and \( \mathbbm {1}_{\{h\}}\) equals 1 if the firm hides the crime and 0 if it does not. The standard Beckerian model of crime deterrence is obtained simply by setting \(K=m=0\) so that \( p^{f}(m/K) =0\). In this case (6) becomes \( E\pi = \beta \pi (1) -p^{g}(m^{g}/K) F\). Let \(\pi (N)\) be the firm’s profit when it behaves honestly. Crime is deterred if and only if \( E\pi \le \pi (N)\), or equivalently:

Since monitoring is costly for the government, it is optimal to set \(m^g\) as close as possible to 0 so that the punishment F goes to infinity (see Becker, 1968). The problem with this Beckerian solution is that it fails to capture limited liability and bankruptcy constraints. The firm will never pay the infinite penalty,Footnote 29 and therefore, the expected loss from corporate crime is not large enough to prevent the crime when \(p^{g}(m^{g}/K)\) is small.

We consider how a more sophisticated approach to sanctions, one that strengthens firms’ incentives to cooperate with law enforcers, might improve the detection of crime, although it is not necessarily sufficient to prevent the crimes from taking place. Assuming that a corporate crime has been committed and the corporate management has become aware of it, which occurs with probability \(p^{f}(m/K)\), the firm will cooperate with the authorities if and only if the expected cost of doing so, \(F^r\), is lower than the expected cost of hiding the crime, \(p^{g}(m^{g}/K)F^{h}\):

Equation (8) shows that, as long as \(p^{g}(m^{g}/K)> 0\), it is always possible, by differentiating punishment, to induce firms to cooperate with the authorities when they discover crime in their operations. Indeed, whatever the maximum value of the fine \(F^h\) that can be imposed on the firm when it has covered up the crime, the government can always decide to set \( F^{r}< p^{g}(m^{g}/K) F^h\). For instance it can choose to grant full leniency in case of self-reporting by setting \( F^{r}=0\). Consistent with results by Spier (1992) and Bigoni et al. (2015), differentiated treatment of offenses can help uncovering the occurrence of corporate crime. By contrast if Eq. (8) is violated so that \( F^{r}> p^{g}(m^{g}/K) F^h\) then the firm never reports a crime.

We deduce that if the government wants the firms to invest in monitoring, sanctions must be set so that (8) holds, in which case there is an interior solution \(m^*>0\) solution to

This allows us to establish the following result.

Proposition 3

If \(p^{g}(m^{g}/K)F>F^r\), then private monitoring \(m^*>0\) solution of (9) and public monitoring \(m^g>0\) are strategic complement:

If \(p^{g}(m^{g}/K)F\le F^r\), then \(m^*=0\).

Proof

See “Appendix”. \(\square \)

Proposition 3 implies that private monitoring \(m^*\) increases with public monitoring \(m^g\). We predict that the probability that a firm monitors, uncovers and reports corporate crime increases with the effort made by the government to monitor its activities. Unless corporate management is aware that its firm’s operations are monitored it will have too weak incentives to commit resources for the sake of efficient policing of corporate activities. Government investment in monitoring, for example by providing sufficient budget for enforcement agencies and encouraging or rewarding whistleblowers, is an essential public good for ensuring market integrity (see also Harrington & Chang, 2015).

The discussion so far has focused on the structure of sanctions, which should encourage firms to cooperate with the authorities, assuming a crime has been committed. An important question is whether, by optimizing this structure, the government can deter crime completely. The next Proposition shows that, in general, it cannot.

Proposition 4

Corporate crime is deterred if and only if:

where \(m^*\) is solution to (9) if \(p^{g}(m^{g}/K)F> F^r \) and 0 otherwise.

Proposition 4 shows that governments face a dilemma in its efforts to control corporate crime. On the one hand, optimal deterrence occurs when \(m^*=0\) so that (11) becomes \( \beta \pi (1)-\pi (N) \le p^{g}(m^{g}/K) F\).Footnote 30 Everything else being equal (i.e., for a given \(p^g\)), condition (11) will not ease the standard Beckerian deterrence condition (7): the probability of detection by the government must be large enough to deter firms from committing corporate crime. On the other hand, when deterrence fails, Eq. (8) shows that to induce firms to cooperate with an enforcement agency it is necessary to differentiate punishment depending on whether the corporate management reports the crime when it is discovered in the firm’s operations or not. The differentiation of punishment decreases the sanctions’ deterrent impact in (11). Leniency programs that differentiates punishment to secure firms’ cooperation with enforcement agencies do not ease the deterrence condition; on the contrary, they make it more binding. In other words, the structure of the fines that encourages companies to invest in monitoring and to cooperate with authorities, \(p^{g}(m^{g}/K)F>> F^r\), conflicts with the goal of deterring them from committing crimes, which requires \(p^{g}(m^{g}/K) F \le F^{r}\). We deduce the next result.

Corollary 1

The government should set \(F=F^h=F^r={\overline{F}}\) so that \(m^*=0\) if \(p^{g}(m^{g}/K)\ge {\beta ^{j} \pi (1)-\pi (N)\over \overline{F}}\). It should set \(F=F^h={\overline{F}}\) and \(F^r=0\) so that \(m^*\) is maximal otherwise.

Corollary 1 shows that, if the probability of detection by the government is large enough to deter firms from committing corporate crime, then there is no need to waste private resources in daily monitoring and preventive measures. The government does not introduce a leniency program and firms have no incentive to commit crime, nor to report any. By contrast if the probability of detection by the government is too low to prevent crimes from occurring when punishment is maximal, then the government should encourage firms to monitor and report crimes to the authorities by offering leniency in case of self-reporting. Leniency programs are an implicit admission that crime deterrence does not work. An interesting result of the Corollary 1 is that there is no incentive benefit to differentiate penalties based on whether or not the firm knew about the offense when it did not report it: \(F=F^h={\overline{F}}\). It means that once a crime is uncovered without the help of the firm, there is no need for the government to commit resources to investigate the firm thoroughly to determine the management’s ex ante awareness of the crime: \(m^*\) in (10) is independent of \(F^h\). It is sufficient for incentive reasons to offer leniency in case of self-reporting and the same level of punishment otherwise (i.e, it is sufficient to have \(F^r< F=F^h\)).Footnote 31

3.3.2 The limits of leniency programs

Antitrust authorities in the United States and in the EU rely heavily on leniency programs to uncover cartel cooperation. According to Carmeliet (2012), the vast majority of EU cartel infringements are discovered through a leniency program. Ysewyn and Kahmann (2018) conducted a review of cartel cases decided under the Commission’s 2006 Leniency Notice, and finds that for most years since then, 100% of investigations were sourced from immunity applicants. As shown in Proposition 3, the incentive effect of offering leniency for those who self-report corporate crime depends critically on governments’ ability to uncover and sanction such offences on its own. In the EU, there is a risk that the Commission and the antitrust enforcement agencies at the national level are relying too heavily on leniency programs to uncover cartel cooperation, which we predict should lead to a decrease in the number of reported cases. As far as we know we are the first to establish such a link between nonleniency enforcement efforts made by anti-trust authorities and the number of immunity applications.Footnote 32

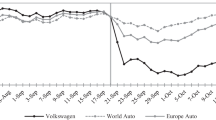

Over the last years there has been a noticeable decrease in the number of immunity applications from firms operating in a cartel, and thus, a possible weakening of the Commission’s ability to detect cartels. By reference to statistics from Global Competition Review, Ysewyn and Kahmann (2018) document a clear decline in the number of leniency applications between 2014 and 2016. According to them, the number of leniency applications (including immunity applications) fell by almost 50% over three years.Footnote 33 While such statistics are difficult to obtain in detail in Europe, there are indications that this might be a trend.Footnote 34 Even if the Covid-19 crisis might explain part of the dip in the last period, recent surveys confirm that practitioners have seen a decrease in interest from their clients to apply for leniency before the pandemic (see for instance Wils, 2017). According to the OECD’s Trends in Competition 2023 report, leniency applications have hence steadily declined over the past seven years worldwide (from nearly 600 in 2015 to fewer than 200 in 2021; see OECD, 2023).

The second concern raised regarding leniency programs ability to uncover collusion, is the consequences of such asymmetric sanctions on the market structure and competition. In cases of cartel cooperation, the firm that self-reports its offence can get full immunity (i.e., a fine \(F^r=0\)) and, on top of that, a competitive advantage if its competitors are all sanctioned.Footnote 35 To illustrate the anti-competitive effect of leniency programs, consider the sanctions of corollary 1, \(F^r=0\) and \(F=F^{h}= {\overline{F}}\), so that the self-reporting corporation profits from a stronger market position after reporting the crime, as its competitors are weakened by the sanction. Assuming the firms face a random shock in their operations affecting their financial viability, \(\xi ^i\) independently and identically distributed in \((0, +\infty )\) according to the density \(g(\xi )\) and the c.d.f \(G(\xi )\), the firm i goes bankrupt if the fine is larger than \(\xi ^i\). The proportion of firms impacted by the penalty that goes bankrupt is: \(Prob\left( \xi ^i\le {\overline{F}}\right) =G( {\overline{F}})>0\). We deduce the next result.

Proposition 5

If a leniency program with fines \(F=F^h={\overline{F}}>0\) and \(F^r=0\) works as intended then after the imposition of the fines there are in expectation \(EN^c=1+ (N-1)\left( 1-G\left( {\overline{F}}\right) \right) < N\) firms left to serve the market.

Proof

See “Appendix” \(\square \)

In other words, every thing else being equal, concentration rises following the asymmetric treatment of the guilty firms in the context of a leniency program. To the best of our knowledge this prediction is new in the literature on leniency, which tends to assume that the number of firms is fixed/stationary. Whether this predicted positive correlation between cartel sanctions and higher concentration holds in the EU context is an empirical question to which we will return later.Footnote 36

3.3.3 Optimal investment in precautionary measures

The analysis related to Proposition 4 revealed that in general, enforcement systems are unable to deter firms from committing corporate crimes. Since monitoring corporate crime is easier and less costly when corporate preventive measures are in place (i.e., when K is larger), the government ought to require firms to take precautionary measures to ensure transparency and induce employees to report crime to the authorities (Arlen & Kraakman, 1997). For instance, a government might require a minimum level of K, which ought to be verifiable, either as a condition to warrant leniency in case of self-reporting, or simply as a mandatory legal requirement. Not investing adequately in crime prevention ought to be considered ex-post as corporate negligence, implying a risk of harsher sanctions and criminal prosecution against individuals.

The optimal level of prevention measures solves: \( \min _{K} \left\{ L(N)\tau (N/K) + NK\right\} .\) If the probability that a crime goes undetected, \(\tau (N/K)\), is decreasing and convex in K then this problem is well behaved (i.e., the minimisation problem is convex),Footnote 37 and the first-order condition is also sufficient. We deduce the next result.

Proposition 6

Let \(\tau (N/K)\) be decreasing and convex in K. The optimal investment in precautionary measures, \(K^{*}\) is such that:

At the optimum, the marginal benefit of increasing K in terms of crime reduction, which is proportional to the loss L(N), should be equal to the marginal cost of increasing it, which is N, the number of firms active in the sector that would all have to bear the cost K. We next study how the optimal level of preventive measure varies depending on the market size Q, and the intensity of competition N. We also study how the critical value \(N^*\) defined in Proposition 1 is impacted by K.

Appendix shows that since L(N) increases with the size of the market Q, as illustrated for instance by (3), it implies that precautionary measures should be larger in larger markets: \( {dK^*\over dQ}>0\). By contrast, the impact of the sector concentration, as measured by N, on the optimal level of precautionary measures is ambiguous. On the one hand, when N is larger, precautionary measures are socially more costly as each firm needs to pay K. On the other hand, assuming the cross-derivative of \(\tau \) with respect to N and K is negative, the marginal benefit of preventive measures K on the expected social loss \(\tau (N/K)L(N)\) increases with N the number of firms active in the sector, pushing up the optimal level of K. Appendix shows that, depending on which of this effect dominates, the optimal level of precautionary measures might increase or decrease with N. Finally, and importantly, we ask whether precautionary measures are useful to control corporate crimes. To answer, we need to study how \(N^*\) defined in Proposition 1 varies with K. Assuming that the cross-derivative of \(\tau \) with respect to N and K is negative, “Appendix ” shows that increasing preventive measures decreases \(N^*\). Minimizing social loss by imposing preventive measures of level \(K^*\ge 0\) defined in (12) on firms, decreases their ability to commit a corporate crime that will go undetected. In other words, imposing preventive measures \(K^*\) solution to (12) limits the number of firms that can conspire without being detected, and therefore, the extent of corporate crimes.

4 Enforcement in practice

In this section, we consider whether real life’s enforcement conditions in the EU, the largest integrated economic zone on earth, correspond to the theoretical results developed above. For this exercise we consider different sources of information. Obtaining relevant data, however, has proven difficult. Detailed facts about enforcement cases are generally shielded from public scrutiny, including from researchers. Evaluating public enforcement of corporate liability is made even more difficult by the use of non-trial resolutions, for which documentation is far more limited than for court proceedings, and where the calculation of the sanction is often poorly substantiated if it is described at all.

For our case studies we selected five countries - Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. For the three areas of corporate liability that we investigated – corruption, money laundering, and violations of competition law (some places referred to as antitrust), countries in Northern and Western Europe have similar regulations, as described in Sect. 2, and this applies to our case countries as well.Footnote 38 Nonetheless, European jurisdictions differ in important ways with respect to both regulatory details and enforcement practice, and in the choice of countries, we capture some important differences. The UK is a common law country, with a stronger plea bargain tradition than the other four countries. Germany is a federation with slightly different practices across its 16 federal states, while criminal law is exclusively a matter of national regulation and enforcement. Sweden and Germany have yet to introduce corporate criminal liability, although enforcement of non-criminal corporate liability is functionally equivalent, as described in Sect. 2. Although such aspects matter for regulatory performance, we simplify our presentation by focusing on specific features of enforcement as they are reflected in the research material and as they compare to the Sect. 3 results.

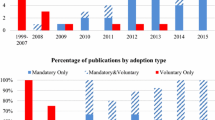

Considering the mentioned five countries, we conducted a search of their legal databases as well as other publicly available databases, supplemented by a general internet search using search engines. Further information was gathered by contacting relevant authorities in the five jurisdictions, with follow-up phone calls as well as formal applications for access to decisions for the purpose of research. This investigation, carried out between June and November 2019, yielded a total of 50 non-criminal and criminal corporate liability cases, including 20 competition law cases, 19 bribery cases, and 11 AML cases (listed in the “Appendix”). We studied this information, along with complementary data, in order to explore the empirical side of our theory’s implications.Footnote 39

Given the 50 cases and the five jurisdictions, we were able to verify at least some of the predictions put forward in Sect. 3. Namely, we investigate the predictability of sanctions and (partly) leniency across jurisdictions (4.1) in order to verify whether the basic assumptions for a well-functioning enforcement system are present. With a view to governments’ incentives, we also explore the relevance of market size and market structure in the sample of cases as well as the geographical location of the consequences of crime (4.2). This is both related to the question about social loss (3.2.1), as well as governments’ inclination to prosecute crimes that are carried out abroad (3.2.2). In a sub-study of competition law cases at the EU-level, for which more facts are available compared to the other two sorts of offences, we investigate the market consequences of a sanction (4.3). The latter section explores the concern of competitive harm stemming from asymmetric treatment of corporate offenders, as demonstrated in (3.3.2).

4.1 Predictability of sanctions and leniency

It follows implicitly from the analysis above, as well as general insights from the economics of crime, including those derived in Sect. 3, that an enforcement system’s ability to deter future crime requires a certain ex-ante predictability of sanctions. Potential offenders ought to know what actions are subject to criminal liability and how the liability is enforced. Likewise, for leniency to spur crime detection as described in Sect. 3, it must be possible for self-reporters to rely on the enforcement agency to reduce the penalty in return for cooperation. Predictable use of the leniency policy is thus essential for its intended impact. With respect to law enforcement more generally, a high degree of predictability implies lower discretionary authority, and thus, less opportunity to deviate from optimal enforcement strategies, including sanction levels. Predictable sanctions requires access to facts about corporate offences (unless such facts are available it is impossible to know whether the imposed sanctions keep a level high enough to deter crime or not). Law enforcement predictability and access to information about the offences committed are therefore relevant for several of the points made in the theoretical analysis.

Based on the information we collected about country enforcement systems, we placed countries on a 1-5 scale (where 1 is the best score) along these two dimensions of facts availability and predictable leniency, as shown in Table 1. The country scores are also broken down by type of offence (bribery, AML, antitrust). The scores are the result of our systematic assessment of the regulations and enforcement practices in the 50 cases reviewed (see “Appendix” for details on their computation). On the left-hand side of Table 1, the country scores reflect the extent to which facts about corporate misconduct and sanctions are available to the public and presented in a manner that makes it possible to assess the proportionality between penalty and corporate misconduct. The harder it is to learn the facts, the higher the score. In countries that score 1, the public has complete access to information about the crime and the sanction, while in those that score 5, it is not even possible for researchers to apply for access to such basic information. The right-hand side of the table presents our scores on the ease with which offenders can predict the sanction reduction (i.e., leniency) they will receive if they self-report and cooperate with law enforcement agencies. Clear guidelines made public and demonstrated application of stated principles in cases earns a score of 1. The score increases the closer we get to a situation where firms have no clear information about the use of sanction reductions upon self-reporting and there is no systematic use of leniency demonstrated in the case material. Hence, Table 1 illustrates variation across the five countries in the extent of access to information about enforcement practices and the clarity with which law enforcers offer leniency to those who self-report.

On each of the two dimensions, we find sanction predictability to be greater in competition law cases than in corruption or AML cases. Information about sanctions is more available to the public in antitrust cases, and the benefits offered to firms that self-report are more predictable. In this respect, enforcement of competition rules seems better aligned with economic ideas of incentives to report crime than enforcement of anti-bribery laws and AML regulations. One likely explanation is the presence of a European supra-national enforcement agency (the Directorate-General for Competition, or DG Comp) in the case of antitrust and the systematic cooperation between competition agencies within the European Competition Network (ECN). There is no equivalent for enforcement of anti-bribery laws and AML regulations. In addition, the rules and conditions for leniency are spelled out much more clearly in legal instruments and case law, bringing about harmonization as well as predictability across jurisdictions.Footnote 40 For the sake of predictability, there is limited discretion with regard to negotiated settlements in cartel cases; either a firm will meet the conditions for leniency, or it can accept a cartel settlement under a procedure adopted in 2008 (with a maximum reduction in the fine of 10 percent).Footnote 41

With respect to bribery and AML-cases, sanction predictability is not only a matter of how well rules are aligned, but also the ’flexibility’ with which enforcement agents enforce the regulations. The more discretionary authority (i.e., flexibility) associated with law enforcement, the less predictable the sanctions. Although such flexibility might be used to optimize sanctions, it likely reduces the deterrent effect of sanctions if it implies reduced sanction predictability.

Enforcement flexibility depends on several factors, such as the content of regulations, the relevant agencies’ de facto and de jure independence, and most importantly, enforcement agencies’ ability to conclude cases without a trial, turning instead to a settlement, formally referred to as a non-trial resolution.Footnote 42 For insight into such variations across the five case countries, we consider the results of a recent survey of regulatory regimes for non-trial resolutions in corporate bribery cases, conducted by the International Bar Association for 66 countries. These data were used to construct a Prosecutor Discretion Index (Søreide & Vagle, 2020). PDI scores for our five case countries are shown in Table 2. This index indicates the position of criminal law enforcement agencies, which is normally responsible for pursuing corporate bribery and AML cases (and not, non-criminal regulation, like competition law cases).

According to these results, prosecutors’ discretionary authority is higher in the Netherlands than in the other four countries, and lower in the UK. The UK has the most explicit regulations for the use of non-trial resolutions, and it is the only jurisdiction that requires judicial review of such enforcement actions. However, in some of the cases reviewed, such as the Rolls Royce bribery case and the XYZ/Sarclad case, the enforcement processes have spurred debates about too-soft treatment of firms that might be considered strategically important by the government.Footnote 43 Nonetheless, the regulatory space for flexible enforcement is at least as broad in the other countries. The Netherlands has fewer regulations when it comes to the use of non-trial resolutions, and often appears lenient with corporate offenders (Makinwa, 2014). Germany and Sweden, on the other hand, have no criminal liability for corporate offenders, and despite strict criminal law procedure, the lack of explicit regulations on non-trial resolutions give their enforcement agencies more leeway when it comes to corporate liability cases. Similarly, Norway has no stipulated principles for non-trial resolutions and no judicial review of such enforcement actions. Taking into account governments incentives, as found in Sect. 3, such leeway might be counter-productive with respect to maximization of consumer surplus.

Summarizing our observations of sanctions predictability across the five case countries, we find far more consistency in enforcement practices in competition law cases compared to bribery and AML violations, regardless of enforcement mode, as reflected by the low scores for antitrust in Table 1. The scores presented in Table 2 apply to the enforcement in corporate bribery cases, yet the scores are relevant for AML cases too. Here we find the enforcement systems of the UK and Sweden being the least flexible with respect to corporate liability, and according to Table 1, comparing all three offences, these two countries have the highest sanction predictability in general as well. Among the five case countries, the Netherlands have the most flexible enforcement in corporate liability cases, and probably, the lowest sanction predictability. Generally, our results are consistent with the fact that prohibitions on bribery and money laundering are subject to the more traditional regimes of criminal law, and such rules are not subject to enforcement at an EU level. Competition law, by contrast, implies that EU Member States are required to introduce legal instruments similar to the powers of the European Commission in their legal orders, and this applies to leniency programs and cartel settlement procedures. Upon this comparison, we find the enforcement procedure and outcome are more predictable where independent specialized agencies have operated for a long time with supra-national cooperation and oversight, and with a clear aim of encouraging offenders to self-report.

4.2 Market size, sanction size, and the geographic location of crime

In this Section, we explore two central issues raised in the theoretical part; the relationship between sanctions and social loss (considering market position and market size), and the predicted reluctance of governments to prosecute crimes abroad.Footnote 44

For sanctions to make a crime unrewarding, the penalty level divided by the risk of detection (expressed as a variable below 1) must exceed the gain from the crime. Clearly, the offenders in the 50 cases considered were not deterred by the risk of a sanction. From the outset, however, we do not know if the reason was recklessness as to the criminal nature of the conduct, a miscalculated risk of detection, an anticipated sanction level below what it would take to make the crime unrewarding, an assumption that if detected, one can negotiate oneself out of the problem by accepting a non-trial resolution, or simply, too little information about enforcement to make such calculations.

Therefore, we want to know if the sanctions in the cases considered held a level high enough to deter similar crime in the future, although in practice, it is difficult to estimate the necessary variables. The detection rate is impossible to quantify correctly unless we know the actual amount of crime incidents. The burden of a penalty is not expressed by the size of the fine alone; it also includes the enforcement process, the payment of damages, the indirect consequences of the case, and any charges brought against employees and business partners. Not all these facts are known, and those that are available are not necessarily shared with the public, not even for research. The details of the cases and the extent of the information we were able to collect are presented in Table 6 in the appendix.

In 26 of the 50 cases, we were not able to obtain reliable information on the final sanction. For the other 24 cases, we have a rough estimate of the gain from crime and the financial size of the corporate fine. Considering these figures we calculate the minimum detection rate required for the penalty to deter crime, assuming the penalty is known to firms. For example, in a cartel case from 2012 against Virgin Atlantic Airlines (VAA) and British Airways (BA), VAA reported the offense, and upon leniency received no penalty. Here the sanction principle applied appears to be consistent with the aim of having the firms cooperating with the authorities (as expressed in Sect. 3.3.1 Eq. 8) because VAA was rewarded fully for self-reporting. Meanwhile, BA received a fine of £58.5 million, and the enforcement agency estimated that BA had a £29 million gain from the offense. For the penalty imposed on BA to deter crime, however, the detection rate must have been nearly 50 percent, which we consider unrealistically high. Therefore, we conclude that the fine imposed on BA was too low for the penalty to deter future cartel cooperation. In a similar manner, and with an assumption that any detection rate above 25 percent is unrealistic, we find that the fines might be high enough to deter similar crimes in a similar situation in seven of the cases, and too low in 17 of the cases, as categorized in Table 3. The letters b, l and c refer to the sort of offence, i.e. bribery, laundering (AML) and competition law, while the letters a and h in the parentheses behind the shortened case-name refer to geographical location of consequences, i.e. abroad and home, as we return to below.

Among the cases where the offender was given a relatively low fine, twelve are bribery cases (Rolls Royce, XYZ/Sarclad, Siemens, Airbus, MAN Ferrostaal, DB Schenker, Ballast Nedam, VimpelCom, Telia, SBM Offshore, Standard Bank (2015-case), and Yara); four are AML cases (ING Groep, Santander, DNB, and Sædberg); and two are competition law cases (Asphalt and the above-mentioned airline price-fixing case). Cases where the penalty might be high enough to deter the offense include three competition law cases (Dutch Railways, TeliaSonera, and the case against Ragn-Sells AB and Bilfrakt Bothnia AB), two bribery cases (Smith & Ouzman and Standard Bank 2015-case), and two AML cases (Santander and Deutsche Bank). Yet the estimated gain is very uncertain in the AML cases. Hence, this material indicates that penalties are often below the level necessary for deterrence in bribery and AML-cases, and appear more likely to reach the level of deterrence in competition law cases (i.e., they are larger). One explanation might be the more explicit regulation of the calculation of sanctions in competition law cases, a matter we will return to below.

Given the theoretical results of Proposition 1, we also wanted to check if the size of sanctions (i.e., whether considered high or low) varied systematically with the offender’s market position. Calculating the ratio between market concentration and sanctions size is not straightforward. Estimates of market concentration are often uncertain because they require identification of a market, and this is complicated for multinationals that operate across industries. Furthermore, crime is more likely in concentrated markets, as predicted in Sect. 3, and this may lead to systematically higher sanctions. Moreover, as we have described above, a penalty that appears to be low might be a result of the offender’s self-reporting, thus consistent with the theory on leniency.

Considering our 50 cases we could estimate the ratio between penalty and market position for 26 of them. For the assessment of concentration, we use the Herfindahl-Hirschman index score, when such information is available, and otherwise, the concentration ratio (Alexeev & Song, 2013; Cavalleri et al., 2019). For each case, we estimated the mark-up ratio for the specific offenders, as a modified Lerner index, and checked for relevant remarks from market analysts and government. Based on this scant material, Table 3 shows in the upper-right quadrant of the matrix those offenders that both operated in concentrated markets and received a relatively low penalty. We find there are more cases of corporate liability in concentrated markets than in markets where firms are exposed to tougher competition, consistently with Proposition 1. In this material, the cases where the penalty is clearly below a level able to deter crime outnumber the cases where the penalty might be at a level high enough to prevent future crime. Whether powerful firms are shielded from sanctions is difficult to tell on the basis of these cases, although Table 3 shows firms operating in concentrated markets are often treated too mildly by law enforcers. Regarding the sectors that happen to be included in our material, banks appear to be more severely sanctioned than other types of businesses (given this set of cases), while defense producers and telecommunication operators have received low penalties. When it comes to variation across the jurisdictions, the ratio between low and possibly deterrent penalties shows Sweden (0/3) and the UK (3/3) are the more likely to impose severe sanctions, while Germany (5/0), the Netherlands (5/0) and Norway (4/1) are the jurisdictions most inclined to impose low penalties.

We also wanted to check whether the geographical location of the crime has an impact on the sanction imposed.Footnote 45 We categorize the cases listed in Table 3 according to crime happening abroad (a) or at home (h). Among the 16 cases playing out abroad, for which we have evaluated the level of sanctions, only four cases (25%) resulted in a penalty that might have been high enough to deter future crime, while 12 of them resulted in a low penalty. In contrast, in the seven cases where the consequences harmed the domestic market, five cases (72%) resulted in a tough penalty, while in two of the cases the penalty was low. In this material, there is a clear overweight of low penalties when the consequences of crime materialize abroad. If there is a tendency to shield powerful firms from heavy sanctions, these cases show, it happens more frequently when they are liable for bribery in a foreign market than when they are implicated in cartel cooperation or AML violation, regardless of market concentration.Footnote 46 In sum, consistently with the prediction of Proposition 2, crimes for which the consequences materialize abroad, especially bribery cases, are sanctioned less severely than the other categories of offenses.

4.3 The impact of sanctions on competition in markets

A problem for governments that are accountable and want to sanction offenders fairly is the risk that the sanction itself may have harmful market consequences. This concern may help explain why governments sometimes seem to shield corporate offenders from sanctions. To understand whether the sanctions themselves make a difference in markets, we collected data on antitrust cases at the EU-level. Information about (de facto) sanction principles is far more available for cartel cases than for criminal cases because the European Commission provides detailed information about all its cases.

Reviewing all antitrust and cartel cases in the period from 1 January 2010 to 10 March 2020, we found 89 cases that resulted in a formal decision. In 73 of the cases that resulted in a sanction, the offenders operated in a clearly distinguished sector (with a unique NACE code), and that fact allowed us to consider systematic variation across sectors. We focus on these 73 cases. Considering 3,363 merger and acquisition (M &A) cases,Footnote 47 we first find that the average number of M &As is 18.1 in the sectors where an offender is fined for anti-competitive behavior (with a median of 11), while it is 8.1 in other sectors (with a median of 4). This finding suggested a pattern across sectors of M &A cases being far more common (nearly double) in sectors where one or more firms have been sanctioned for anti-competitive behavior, compared to other sectors.Footnote 48 To investigate the strength of the pattern we run linear regressions, which methodology is detailed in “Appendix”. The results confirm a highly significant difference in the rate of M &A between industry groups (identified by their specific NACE code) with and without a sanction. Several versions of these linear regressions were run to assess the effect of a sanction on the M &A rate. Results are shown in Table 4.

First, we define a dummy variable equal to 1 if a sanction has been applied and regress it on the number of M &A cases that occurred during the period studied. We observe in the first column that on average, the number of M &A cases increases by a factor of 2.23 (= exp(0.802)), which corresponds to 9.98 additional cases when a sanction has been imposed (relatively to cases with no sanction). Since M &A is driven by industry-specific forces and not solely, nor even primarily, by sanctions imposed by competition authorities, we control in a second and third specification for the industry in which M &A takes place. In the specification presented in column 2 we use the level 1 of the NACE code (19 broad categories) as a control. In the specification of column 3, we use the level 2 of the NACE code (84 categories). As expected the coefficient of sanction is smaller when we control for sector characteristics. However the sanction dummy remains large (at 0.634 with 19 sector controls; 0.401 with 84 sector controls) and highly significant. This implies that on average, the number of M &A cases increases by a factor of 1.5 (= exp(0.401)).

Second, we check the robustness of this base result by using other measures for the sanctions. In columns (4), (5) and (6), we reproduce the same analysis as in columns (1) to (3), using the duration between the date of the first fine and the end of the period studied (10/03/2020), so that when no sanction was imposed the value of “Time with sanction” is 0 and strictly positive and increasing when sanctions were imposed earlier, instead of the sanction dummy, with and without the NACE codes. Finally, in columns (7), (8) and (9), we run the same regressions with the log of amount of the sanction as an independent variable. These two robustness checks confirm a higher M &A frequency in sectors where firms have been subject to antitrust sanctions. The three set of regressions yield similar and consistent results.

This result might reflect in part the market structure as formalized in the theory: there appears to be a clear over-representation of firms sanctioned in high-concentration markets (i.e., they are characterized by a low N which implies in the theory that the probability of collusion is higher). For example the fined sectors contain a higher number of cases related to network utility sectors, such as production and trade of electricity and gas, industries that are already more concentrated by nature, akin to their natural monopoly characteristics (see “Appendix”). Markets prone to cartelization are also presumably more inviting to horizontal mergers as well, as collusion requires coordination and cooperation between firms. These illegal agreements might be a stepping stone for more formal ones, i.e., acquisitions and mergers.

To further explore the heterogeneous effect of sanctions on sectoral mergers and acquisitions, we interact Sector with Sanction. To avoid having too many interaction terms, we group the level 1 sectors that do not have enough observations together: sectors C, D, H, J and K have enough observations to be kept, while the other are grouped together. The interaction effects in column 4 in Table 7 show that sector C (Manufacturing) and Sector J (Information and Communication) deviate significantly from the omitted category, which is evidence that in sectors C and J, the Sanction effect on M &A is higher than in the other sectors. From these observations we infer that, indeed, the sectors play an important role in explaining the impact of Sanction on the number of M &As.