Abstract

Trafficking in human beings (THB) is a widespread, transnational issue in the European Union (EU). Member states act as source, transit, and destination countries for intra-EU trafficking, in addition to being a major destination region for external THB victims. This study presents a new dataset of THB victims observed in each EU member state per year and by type of exploitation going back as far as 2001 and employs exact matching methods to test the link between different prostitution policies and Roma secondary education attainment rates on observed THB victimization. The paper also builds off previous literature to compare how different legal prostitution models and THB supply factors are expected to influence various types of THB. The results indicate that legalized prostitution and lower educational attainment among the Roma community increase observed THB victimization, especially THB for the purpose of sexual exploitation. The paper does not find that the Swedish model significantly increases or decreases observed THB victimization. In demonstrating how matching methods can be utilized to uncover policy patterns in THB outcomes, this study provides a blueprint for how other hidden phenomena, such as corruption or migration, can be robustly and empirically tested.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Trafficking in human beings (THB) represents both the persistence of modern slavery and an intensifying rise in the exploitation of vulnerable populations and individuals. Whether in its form as trafficking for the purpose of sexual exploitation (commonly referred to as “sex trafficking”), forced labor, labor exploitation, forced begging, forced criminality, forced marriage, organ trafficking, or its other types, THB poses a social welfare, security, crime, and economic policy problem. THB, as a political and legal problem, is particularly complex in the EU since THB is pervasive, exists in both transnational and internal trafficking forms, and requires member state and EU-level policy leadership and legal responses. Indeed, the European Commission (2020) noted that approximately half of all EU THB victims are EU citizens, one-third of EU victims are trafficked internally while the other two-thirds are trafficked in other member states, and THB criminal networks are increasingly sophisticated and operate across state borders (3). 7482 adult THB victims were recognized in 2018 and 11,062 adult THB victims were recognized in 2019 across twenty-three EU countries (this study). THB is also a highly lucrative illicit industry, with forced labor profits alone making $150.2 billion per year (ILO, 2014), 50% more than the value of the global arms trade (SIPRI, 2021).

THB is recognized as a primarily transnational and international issue as the phenomenon frequently involves the movement of victims across borders. However, most global THB is in fact internal and intra-regional (UNODC, 2009) with the distinction between domestic and external trafficking becoming blurred in the EU since the Schengen Area provides most EU citizens with freedom of movement throughout the bloc (European Commission, 2021n). The freedom of movement in the EU complicates not only how THB is identified, but also the effectiveness of domestic member state policy in combatting THB and protecting victims within their borders. Internal trafficking can spill over into surrounding states as potential victims are recruited for domestic exploitation but may be moved across borders for re-trafficking. In the sex market alone, upwards of 67% of external THB victims may have entered the sex market in their home country before being “re-trafficked” abroad (Kelly, 2002, 31). The transnational nature of THB and the re-trafficking phenomenon makes the movement of vulnerable individuals (even within their own state) the distinguishing feature of trafficking. The European Commission’s Directive 2011/36/EU defines THB as “the recruitment, transportation, transfer, harboring or receipt of persons, including exchange or transfer of control over that person, by means of the threat or use of force or other forms of coercion, of abduction, of fraud, of deception, of the abuse of power or of a position of vulnerability or of the giving or receiving of payments or benefits to achieve the consent of a person having control over another person, for the purpose of exploitation” (European Parliament and European Council 2011).

In response to the challenges of THB, prostitution models—such as legalized prostitution and the Swedish model—are designed to constrain the sex market in a way that regulates its legality and/or lowers THB for the purpose of sexual exploitation. The Swedish model (also referred to as the Nordic model) decriminalizes the act of prostitution while criminalizing the purchase of sex (Friesendorf, 2007). And legalized prostitution regulates the sex industry but legalizes the purchase and sale of sex (ibid). The Swedish model is preferred by “abolitionists” who believe prostitution is equivalent to rape and the sex industry profits from gender-based violence, while legalization is favored by advocates who believe prostitution can be liberating and that regulating the sex industry by requiring sex workers to formally register, pay taxes, and (sometimes) receive welfare benefits reduces the risk of exploitation within prostitution (ibid; Cho, 2016). Policymakers also try to address THB “push” and “pull” factors and labor market vulnerabilities to confront labor exploitation and other types of THB. THB is, more broadly, driven by numerous “push” and “pull” factors that incentivize individuals into vulnerable work and citizenship situations, and/or illicit industries. “Push” factors increase the vulnerability, and therefore subsequent dependency, of potential victims on traffickers and may hinder their ability to seek help, while “pull” factors in destination countries, such as demand for seasonal work and higher wages, encourage illegal or risky migration (Paraskevas & Brookes, 2018). Other “push” factors include social exclusion, lack of education, poverty, unemployment, conflict, political unrest, discrimination, marginalization, informal work, and migrant status (ibid; Andreas, 2008; Boyle & Shields, 2018).

Since “push” and “pull” factors are therefore regarded as the key determinants of the supply of THB victims, it is crucial to empirically test whether this is, in reality, reflected in the data on THB supply. Towards this end, this study is the first of its kind to test the causal relationship of different prostitution models and a lack of educational attainment among Roma communities via exact matching, and it is also the first to use a newly-collected dataset on the quantity of trafficking victims identified in each of the twenty-seven EU member states. This paper also attempts to surpass the normative debate over how the sex industry affects women’s autonomy and gender equality to empirically and quantitatively evaluate how each of these models affects THB victimization. In the following sections, I will review the literature on how public policy and legal models are theorized to influence, and hopefully minimize, THB before presenting hypotheses on how prostitution models and macroeconomic inequalities affect THB victimization, discussing this paper’s matching methods, and introducing my original dataset. Quantitative results are then explained before elaborating on how matching methods can further scientific inquiry into hidden economic activity, including illegal acts such as corruption and smuggling.

2 Literature review

This section is divided into two parts: one comparing prostitution models, and the other assessing how socioeconomic inequalities affect THB supply. This is helpful because the prostitution policy debate typically only addresses THB for the purpose of sexual exploitation, while socioeconomic “push” factors are related to all forms of THB and are especially important in the labor exploitation conversation. Since this paper considers causal mechanisms for both types of THB, I investigate each perspective and their connections to the “push” and “pull” factors for multiple types of THB victimization.

2.1 Prostitution policy comparison

The “Nordic” or “Swedish” model of prostitution bans prostitution while embracing gender equality values by criminalizing the purchase of sex but decriminalizing the sale of sex (Crowdhurst & Skilbrei, 2022, pp. 98–100). The policy, first implemented in Sweden with the passage of the 1999 Sex Purchase Act, was meant to be exported to other countries, influence international norms on prostitution and sex work, and abolish prostitution by limiting the sex market and changing societal attitudes towards prostitution (ibid). In one form or another, the policy has been adopted by Norway, Iceland, Canada, France, and Ireland (ibid). Regulated and legalized prostitution instead permits individuals to buy and sell sex within the regulated sex market, requires the licensure of brothels, and gives local police, inspectors, tax authorities, and the criminal justice system oversight on prostitution (Huisman & Kleemans, 2014). Even though legalization has practical elements of regulation, it is driven by a moral perspective that views prostitution as “regular labor, governed by market forces” and therefore no different from other types of legitimate, state-regulated work (Brants, 1998, p. 623). The Swedish model and legalized prostitution therefore overlap in decriminalizing the sale of sex, but diverge on perspectives of how buyers should be treated by the criminal justice system and how the state should engage with prostitution and sex work more broadly.

Scholars who support legalized prostitution argue legalization provides prostitutes legal avenues to report abuse to the police and to have dignity as official workers in a regulated profession, improves health outcomes amongst sex workers, gives brothel owners the freedom to report suspected trafficking cases, and strengthens criminal codes against forced prostitution (Zeegers & Althoff, 2015). They criticize the conflation of all prostitution with sex trafficking, which typically follows from abolitionist thinking on prostitution (ibid). These scholars accept, however, that the regulatory aspect of legalization can also have drawbacks to its own aims, such as driving smaller brothels out of the market and therefore part of the sex market into illicit and unregulated territory (Brants, 1998; Huisman & Nelen, 2014; Post et al., 2019). And they recognize that well-known cases, such as the Dürdan case in the Netherlands, demonstrate that severe forms of sexual exploitation can still occur under legalized, regulated sex markets and that a high percentage of sex workers may be coerced into the industry (Zeegers & Althoff, 2015, p. 367). Support for legalization is also indirectly advanced by criticizing weaknesses in the Swedish model.

Scholars have identified flaws in the Swedish/Nordic model, usually directly in the Swedish context. They claim that while street prostitution may have declined under the Swedish model, it may have increased in other hidden forms and indoor spaces, resulting in further vulnerabilities for prostitutes and shorter time spans negotiating with clients – although this evidence relies exclusively on interviews and media sources (Kingston & Thomas, 2019, p. 429; Levy & Jakobsson, 2014). There are also opportunities for prostitutes to be criminalized through immigration policies instead of prostitution ones, as many prostitutes in the Nordic countries are foreign and may face deportation instead of state help in leaving the sex market (Vuolajärvi, 2019). Furthermore, the criminalization of buyers may promote sex tourism into states with more relaxed regulations, such as the observed inflow of Swedish sex buyers to Latvia and Denmark (ICMPD 2009, p. 107), and the subsequent growth of prostitution demand in Norway and Denmark after Sweden adopted its namesake model in 1999 (CATWA 2017, p. 13). The efficacy of the Swedish model within a country may therefore be weakened within a state by lackadaisical implementation or countervailing immigration policies, and across entire regions by a lack of prostitution policy synchronization.

Just as there are arguments against the efficacy and moral positioning with the Swedish model, there are counterpoints to legalized sex work. Scholars who oppose legalized prostitution demonstrate that this policy can incentivize underground prostitution as sex workers wish to evade taxes (Friesendorf, 2007; Business Insider, 2019), foreign prostitutes may not have the required visa status to register with the state and receive protections (Friesendorf, 2007), organized crime related to trafficking may become more profitable and subsequently produce upticks in concealed prostitution activity (ibid), the sex market may enlarge (ibid), and only as little as 10% of sex workers may officially register (Business Insider, 2019). Street prostitution has also been shown to persist in countries with legalized prostitution, as is exemplified by the situation in Riga, Latvia (Baltic News Network, 2020). On the issue of THB victimization and forced prostitution, quantitative empirical studies have produced evidence that legalized prostitution is correlated with THB inflows (Cho et al., 2013; Jakobsson & Kotsadam, 2013) and has not led to improvements in victim protection policies (Cho, 2016). These studies therefore suggest that efforts to root out forced prostitution through legalized oversight of the sex market have not been successful in practice, and may have incentivized traffickers to move their activities to states with forms of legalization. Lastly, Huisman and Kleemans (2014), in a study on the Netherlands, find that countries with legalized prostitution continue to struggle with organized trafficking groups, the regulation of the sex market does not create the transparency necessary to report, identify, and separate sex trafficking from legal sex work; and prosecuting trafficking could potentially be more difficult under policies of legalized prostitution.

Finally, the Swedish model may be better at preventing forced prostitution. There is consistent evidence that the Swedish model has been effective at reducing street prostitution (ICMPD 2009; Socialstyrelsen, 2004), lowering the quantity of prostitutes (an indirect proxy for THB supply), and slowing or ending expansion of the sex market (Coalition Against Trafficking in Women Australia, 2017, pp. 12–16). Both France and Sweden have witnessed a decrease in prostitution demand and a less successful trafficking industry for sexual exploitation under the model (Human Thread Foundation, 2019).

2.2 Socioeconomic inequalities, education, and THB supply

While prostitution policies account for how policymakers can address the demand for prostitution, they tend to ignore the social and economic “push” factors that drive the supply of prostitution (Friesendorf, 2007). Policy interventions which address the macroeconomic inequalities driving socioeconomic “push” and “pull” factors are therefore needed to address the demand for labor exploitation and other forms of exploitation (such as forced begging and forced criminality) and the supply of THB victims. Poverty is one of the most well-cited “push” factors throughout the literature as it can be the difference between a migrant finding regular work or labor exploitation abroad. As is argued by Andreas (2008), impoverished migrants are more likely to end up as victims of forced labor than other migrants because they lack the social capital to navigate informal recruitment and seasonal employment safely. Since both legitimate and illegitimate migrant recruitment firms use informal recruitment strategies and subcontracting to hire migrants, poverty can make potential THB victims more dependent on exploitative work options and more vulnerable to recruitment by hidden THB networks; furthermore, countries with higher poverty rates are correlated with more THB victims (ibid; David et al., 2019).

Some scholars in the forced labor and THB for the purpose of labor exploitation literature, however, disagree on whether migrants’ social networks protect or endanger those at risk of labor exploitation. Indeed, not all migrants are exposed to THB for labor exploitation risks, and individuals who face labor exploitation may be citizens, regular migrants, or irregular migrants (van Meeteren & Wiering, 2019, p. 108). The picture that emerges of how “push” and “pull” factors influence THB for the purpose of labor exploitation, and THB more broadly, therefore requires a more nuanced assessment of how poverty, a lack of opportunity, social exclusion, and societal marginalization influences THB victimization. For instance, Ollus et al. (2013) found in Estonia and van Meeteren and Wiering (2019) in the Netherlands that THB for labor exploitation victims typically found their exploitative job abroad based off the recommendations of employers and bosses by their migrant social network. Yet, having a good social network is also a crucial factor in whether or not a migrant has options to leave the exploitative situation (Ollus et al., 2013). Complicating this understanding of the role of social networks in labor THB is that the goal of most victims is to earn enough money to pay off their debts to the traffickers and send remittances to their families at home (Villacampa, 2022).

Part of the reason that the scholarly image of THB for labor exploitation is murky is that it is an under-researched area of THB, it is conceptualized differently across states (Cockbain et al., 2018); and because victim service professionals tend to be trained to identify victims of sex trafficking—not labor exploitation—and to only be on the lookout for female victims when they are aware of the prevalence of labor exploitation (Villacampa, 2022). Nonetheless, forced labor can be identified as involving “physical or sexual violence or the threat of such violence, restriction of movement of the worker, debt bondage or bonded labour, withholding wages or refusing to pay the worker at all, retention of passports and identity documents, and the threat of denunciation to authorities” (Ollus et al., 2013, p. 14). And labor exploitation more generally encompasses immoral labor practices like overworking employees and underpayment or withheld wages, but also the more severe instances of forced labor and THB for labor exploitation; it can happen in legal and illicit business practices (Davies & Ollus, 2019). While knowledge of sex trafficking is widespread, THB for labor exploitation is rarely known or identified, even by police officers and judges (Ollus et al., 2013). Migrants must typically pay recruitment firms expensive sums to be moved and then employed abroad (ibid). But this implies that migrants from poor, but not extremely poor, backgrounds are those “pulled” into THB for labor exploitation; they must be wealthy enough to incur these upfront costs, but poor enough not to be able to leave the situation abroad once there (van Meeteren & Wiering, 2019).

On the THB for sexual exploitation side, women’s poverty and socioeconomic exclusion may also explain movements into sex industries outside of their home country. The prevalence of foreign prostitutes or sex workers in EU member states, particularly in western Europe, suggests that economic transition, poverty, and conflict dislocation can drive women into the foreign sex industry under conditions of “coerced” willingness (Kelly, 2002). Ethnic minorities like the Roma are particularly vulnerable to THB for the purpose of sexual exploitation or forced begging because they face an added layer of institutional discrimination that undermines the state’s willingness to prevent THB among their communities (Jovanovic, 2015). Furthermore, in the seven EU member states studied by Dimitrova et al. (2015), the Roma were found to be overrepresented in sexual exploitation victims’ data and constituted 90% of forced begging victims (14). Empowering the Roma community, especially Roma women, may therefore be an imperative THB prevention strategy, and this is therefore why this minority group is the subject of further policy exploration in this paper, along with the fact that the Roma community is the largest ethnic minority in Europe (Friesendorf, 2007, p. 389; European Parliament, 2022).

Education can be a particularly powerful means of confronting the “push” factor of modern slavery. Especially in Roma communities—which are significantly more likely to lack formal education and to rely on contributions from children’s wages and work in informal sectors (Pantea, 2006)—education can be a tool for tackling ethnic discrimination, socioeconomic exclusion from the labor market and other parts of society, and poverty (ERRC, 2014). Roma children face exclusion from formal education for a variety of reasons; structural reasons include consignment to remedial classes or institutions designated for mentally disabled students, economic reasons such as a lack of electricity and funds for school materials, and by choice to perform household duties (typically for girls) or work in informal jobs (like agriculture or construction for boys) and begging (Pantea, 2006, pp. 21–24; UNICEF, 2011, p. 19; ERRC, 2014). To put into context the gravity of the educational hurdles faced by Roma children, less than two-thirds of Roma children finish primary school (Ivanov et al., 2006, p. 29) and as little as 18% of Roma children ever enroll in secondary school (UNICEF, 2011, p. 2).

The literature therefore suggests that member states should address sources of poverty and socioeconomic inequality to reduce the supply of THB victims for all types of exploitation. While the demand for seasonal and migrant labor is unlikely to be addressed by working against poverty and social exclusion, empowering vulnerable communities that are mostly likely to engage in irregular and informal work via education lowers their potential dependency on trafficking networks and raises their social capital and regular work opportunities.

Hypotheses

Based on the literature’s prediction that the Swedish model may be better in limiting prostitution demand, and findings by Jakobsson and Kotsadam (2013) that states with legalization are correlated with greater THB inflows, I posit that legalized prostitution increases the quantity of observed sexual exploitation victims while the Swedish model decreases the quantity of observed sexual exploitation victims.

I do not expect legalized prostitution and the Swedish model to have an effect on labor or other types of exploitation (such as forced criminality and forced begging) as they are designed only to address THB driven by forced and hidden prostitution.

H1

Legalized prostitution increases the quantity of observed sexual exploitation victims and has no effect on the quantity of labor or other types of THB exploitation victims.

H2

The Swedish model decreases the quantity of observed sexual exploitation victims and has no effect on the quantity of labor or other types of THB exploitation victims.

Finally, the unique vulnerability of marginalized communities indicates that greater educational inclusion experienced by the Roma should lower the quantity of all types of THB victimization as this community is more likely to experience “push” and “pull” factors. The Roma community is the focus of this hypothesis due to data availability and the fact they are the largest ethnic minority in the EU (European Parliament, 2022).

H3

Greater secondary educational attainment of the Roma community decreases the quantity of observed sexual, labor, and other exploitation THB victims.

3 Methodology and data

This study utilizes OLS regressions with exact matching to establish the independent effect of legalized prostitution, the Swedish model, and high educational attainment among the Roma community on the observed quantity of THB victims by type of exploitation. Pre-processing observational data via matching methods allows the researcher to establish the average treatment effect on the treated (ATT) of the independent variable as if a randomized experiment were performed since exact balance is achieved on observed covariates and on average balance is achieved on unobserved covariates (Ho et al., 2007; King, 2020). Matching on covariates therefore acts “as if” random assignment of the treatment occurred and eliminates parametric assumptions (Ho et al., 2007). Matching, as a blocked experiment, also removes the possibility for bias from researcher discretion, lowers standard errors, and is more robust when compared to completely randomized experiments (King, 2020). The exact matching method was chosen for this paper because it suffers less from the “curse of dimensionality” and model dependence than Mahalanobis distance matching and allows the pre-processed matches to be paired (ibid). The MatchIt software for R (Ho et al., 2011; Greifer 2021) was used to generate the OLS regression results with exact matching. The basic regression equations were as follows:

Each equation was run separately with the quantity of sexual, labor, and other (which encompasses forced labor, forced begging, and miscellaneous exploitation types as outlined in Appendix A) exploitation victims as the dependent variable. Information on how member states were coded as having legalized prostitution or the Swedish model for each country-year is provided in Appendix B. Data for the a later additional socioeconomic control variable (the regional gender employment gap) were sourced from Eurostat (Eurostat, 2021b). And data for the educational attainment rates amongst the Roma were sourced from the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (2011).

The presence of a sufficient national rapporteur was included as a control variable because this monitoring mechanism may affect how well THB victims are identified by the state. Each member state’s type of THB (as an origin, transit, and/or destination country) is also controlled for since states may be predisposed to experience THB as a source, transit, or destination country based on their wealth and inequality levels (Frank, 2013a, 2013b). And country-specific characteristics, like GDP per capita and inflation, were included to account for how countries with more resources and a stronger economy may have greater state capacity in anti-THB efforts or may be better at detecting THB victims (Bowersox, 2018; Jakobsson & Kotsadam, 2013). Dummy variables for each year and country were included to control for time and place fixed effects. Also, age of consent was a control variable in regressions where the quantity of sexual exploitation victims was the dependent variable since varying standards of statutory rape may affect who is registered as a THB victim. And the percentage of the population that achieved tertiary education was controlled for in the macroeconomic inequality regressions as relative educational attainment may affect the magnitude of socioeconomic inequalities on THB victimization. GDP per capita and annual inflation rate data were sourced from the World Bank (2021a; 2021b), the age of consent data were sourced from the Age of Consent legal group, and some of the THB state type coding was based on Frank’s (2013a, 2013b) dataset.

Before each regression was performed, the country-year observations were exact matched on the presence of a sufficient national rapporteur, origin country, destination country, and year covariates. Balance on the covariates is depicted in Appendix D. The application of exact matching methods to a study on THB is exciting as it is the first blocked experiment within the THB literature. As such, it may be the sole study that can establish a causal link between the policy interventions of interest and observed THB victimization, particularly since Jakobsson and Kotsadam (2013) and Cho (2016) suffer from parametric assumptions, model dependence, and the limitations of the 3P, UNODC, and ILO datasets. This is also the first study to establish a causal link between various socioeconomic “push” factors and observed THB victimization. And given the widespread concerns anti-THB scholars have that current recommendations and conclusions are based in non-empirical and purely qualitative analysis, and that the illicit nature of THB and the vulnerable nature of its victims constrains available data collection, this paper takes on Cockbain and Kleemans’ (2019) and Davy’s (2016) call to provide robust scientific evidence with transparent data collection methods. Information on how each country-year observation was coded on these variables and data sources for all variables are detailed further in Appendix B.

Moreover, this study’s pairing of a new, cross-country comparative dataset with exact matching rectifies a particularly challenging problem the THB literature faces – how to apply quantitative analysis and inferential statistics to the field, and how to do so by type of trafficking victimization (Cockbain & Bowers, 2019, 13). For instance, in undertaking a systematic review of previous human trafficking literature, Cockbain et al. (2018) found that there were far more qualitative than quantitative studies on trafficking, those that were quantitative barely met basic scientific requirements, and the studies overall focused on sex trafficking to the detriment of inquiry into trafficking for the purpose of labor exploitation or domestic servitude. Villacampa et al. (2023) also note that THB studies struggle to gather consistent quantitative data, and that those who do so successfully typically focus on sex trafficking and female victims; data on men and boys who are THB victims is sometimes even discriminatorily excluded from empirical studies (161–163). In a field where only 12% of papers from Europe meet minimum scientific standards (Cockbain et al., 2018, p. 332), it is crucial to advance the scholarship forward with rigorous empirical approaches to all forms of THB.

4 New dataset: dependent variable

A new dataset that compiles the quantity of THB victims per year and by type of exploitation in each EU member state was completed for this paper using annual reports from national rapporteurs or equivalent mechanisms, and directly contacting relevant officials for the anonymized, aggregated data in instances where these reports were insufficient. The unit of observation is therefore the country-year quantity of THB victims by type of exploitation.

This data collection endeavor was important because victims’ data is only sporadically reported by the European Commission and is consistently, but not transparently and potentially inaccurately, reported by the UNODC. As the UNODC (2014) admit in their 2014 report, a high proportion of states only partially report THB data to the UNODC and their annual questionnaire only asks for statistics on the quantity of victims formally identified (18). Since the UNODC does not disclose whether countries are instructed to provide data from certain entities before others, it is unclear and impossible to independently determine how comparable victims’ data are between countries and over time in their data set. By reporting further details on data collection and sources for each member state in Appendix A, and prioritizing victim metrics reported by national rapporteurs and nationally recognized victim assistance shelters throughout the data collection process, I hope this dataset will open up opportunities for more accurate and transparent empirical studies to be conducted on THB outcomes beyond this current publication. Baseline descriptive statistics from the new dataset are listed in Appendix C.

The new dataset presented here is crucial to advancing empirical and inferential investigations of how countries’ legal approaches to prostitution affect the scale of sex and human trafficking. Prominent critics, such as Weitzer (2015), have critiqued such investigations for lacking empirical and quantitative analysis, using poor data sources (such as those provided by the European Commission and UNODC) when they are rooted in statistical analysis, and lumping estimates for different types of trafficking together (84–86). My new dataset, however, distinguishes between trafficking for the purposes of sexual, labor, and other types of exploitation, sources primary data directly from the ministries responsible for anti-trafficking measures, and allows me to undertake both an empirical and quantitatively rigorous analysis. Furthermore, Weitzer (2015) criticizes these data sources directly for relying on a variety of sources that are not directly comparable (such as data reported by the media, NGOs, and different governmental departments; 84–85). While at times this new dataset had to rely on data from NGOs (as in the case of data collection on Austria, France, and Italy), this was limited to cases where the government requested designated NGOs to collect and store the data on their behalf. In all other cases, the data was collected by contacting the ministry or department tasked with preventing and tracking human trafficking by the state and/or using and verifying these authorities’ online archives and reports.

The closest comparison to my own dataset is that created by Villacampa et al. (2023). In a very innovative approach, the authors sampled 757 professional bodies and authorities in Spain that work directly with THB victims and asked them to report in their questionnaire the number of victims they worked with in the past two years by type of THB exploitation. These authors’ data collection work is impressive; however, CITCO’s measures, instead of those recorded by Villacampa et al. (2023), were employed in my own dataset because CITCO acts as Spain’s national rapporteur, and is therefore the entity designated by the EU as responsible for official observed statistics on THB victimization.Footnote 1 Jiang and LaFree (2017) also tried to operationalize observed THB victimization using administrative data (crime and policing statistics) reported to the Eleventh United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice System. While the present author has not checked the validity of that survey, it may be flawed like those conducted by the UNODC, and Jiang and LaFree (2017) do not suggest that they checked the validity of the UN survey’s reported data with the official reports produced by national police bodies. My dataset is also more robust since it required me to communicate directly with the ministries and departments responsible for THB victimization data collection, sparked a direct conversation between the policy officials and myself on which statistics are preferable in empirical studies, and uses data produced by the entities responsible for member state THB data collection under Directive 2011/36/EU. I note, however, that caution should still be applied to this new dataset. The dataset is an approximation of observed THB victimization and, no matter how legitimate the data source, relies on the reporting mechanisms of individual states. It is my hope that the new dataset presented here goes one step further in making the study of THB more empirical, scientific, quantitatively-driven, and transparent for analysis, criticism, and fruitful debate; albeit my claims can only be applied to observed THB.

In sum, by providing a new dataset that rectifies systemic errors made in data collection and sourcing by the UNODC and European Commission, scholars can more accurately analyze the effect of prostitution model type (and other policy interventions) on THB outcomes.

5 Results

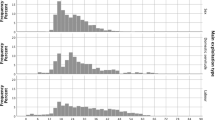

Table 1Footnote 2 shows the OLS regression results of legalized prostitution and the Swedish prostitution model on the quantity of observed sexual, labor, and other exploitation THB victims (after exact matching was performed, as is true for all the regression results presented here). Legalized prostitution has a statistically significant, positive effect on observed sexual and labor exploitation victimization, with this prostitution policy correlated with hundreds of more THB victims in each member state per year, therefore rejecting the null first hypothesis. The Swedish prostitution model does not have a statistically significant effect on any category of observed THB victimization, and therefore I fail to reject the null hypothesis that the Swedish model has no effect on the quantity of THB victims observed.

Table 2 displays the same regression results when a control variable for the size of the gender employment gap and the interaction effect between the prostitution model of interest in the regression and the gender employment gap. The gender employment gap measure deployed in these regression models estimates regional disparities in male and female employment at the NUTS 2 regional level within a country. Even with these additional controls, legalized prostitution has a positive, statistically significant, and even more practically significant effect on the quantity of observed sexual and labor exploitation victims. The effects from the Swedish model are not statistically significant, as well as the coefficients on the gender employment gap (GEG) and the interaction term of the GEG with legalized prostitution or the Swedish model.

Lastly, Table 3Footnote 3 displays the regression results of high rates of Roma secondary education on the different categories of observed THB victimization. A high proportion of Roma individuals completing school has a negative and statistically significant effect on observed sexual exploitation victimization. This outcome is consistent with the predictions from the literature as the Roma community are overrepresented in sexual exploitation THB. The presence of a national rapporteur also had a negative, statistically significant effect on observed THB victimization and this effect was to the magnitude of nearly a thousand victims per year in the sexual exploitation THB categories.

5.1 Discussion

The baseline results in Tables 1 and 2 provide evidence in favor of the legalized prostitution arm of H1 that legalized prostitution increases the quantity of observed sexual exploitation THB victims. This is consistent with previous findings by Jakobsson and Kotsadam (2013) that legalized prostitution is correlated with higher THB inflows and with Cho (2016) that legalization does not improve victim protection. The results in Table 2 lend even more credence to the statistically significant, positive correlation between legalized prostitution and a higher observed quantity of sexual exploitation victims because its models included controls for the gender employment gap (GEG) and interaction effect of the legal prostitution models and the GEG. These controls were important to include because GEG can act as a “push” factor for internal trafficking, or trafficking within a specific EU member state. Thus, by controlling for country characteristics – such as GDP per capita and inflation – which may drive trafficking to other member states, and an internal country characteristic which may foster internal displacement or desires to take risks in illicit or exploitative work conditions, the models in Table 2 should display a more unbiased effect of legalized prostitution (or the Swedish model) on the quantity of observed THB victims. And, surprisingly, Tables 1 and 2 suggest that legalized prostitution can affect observed THB for the purpose of labor exploitation in addition to THB for the purpose of sexual exploitation.

The observation that legalized prostitution can affect other types of THB besides THB for the purpose of sexual exploitation demonstrates that the transnational, professional nature of trafficking may mean that drivers of supply and demand for one type of THB may spill over into other sectors and forms of abuse. While not explicitly outlined in much of the labor exploitation literature, similar mechanisms which facilitate THB for the purpose of labor exploitation—such as predatory recruitment firms—may also be supplying potential sex trafficking victims to some member states, particularly if sex work is a recognized occupation. This warrants further study into overlaps between different forms of THB and how the scale of trafficking networks for sexual and labor exploitation within a country may produce “positive” externalities for the other form of trafficking, or how legal loopholes and institutional capacity failures within a state may help both illicit industries thrive under the radar. The evidence presented here may also reflect some noise in the data since the outcome is observed THB; i.e., some of the correlation between legalized prostitution and observed victimization for THB for the purpose of labor exploitation could be attributed to which states are better at monitoring THB victimization.

The results in Tables 1 and 2 are null for the Swedish model, and therefore I cannot make any conclusions on if the Swedish model in practice prevents, avoids, or even increases observed THB victimization. The fact that the Swedish model does not significantly increase or decrease observed THB victimization does not side with one side of the literature on this prostitution model or the other. It is, however, compatible with the literature at large, which is frequently overcome with conflicting empirical interpretations of realities on the ground in states with the Swedish model, and yet there is consensus among scholars that more nuance is needed in understanding the model’s implications (Jakobsson & Kotsadam, 2013; Kingston & Thomas, 2019; Vuolajärvi, 2019). Further empirical study on the long-term and wider-scale impact of the Swedish model on the scale of THB victimization is therefore also necessary.

In sum, the implications of the results in Tables 1, 2 and 3 suggest a potential need for amendments to legalized prostitution to provide more victim protection and reduce spillover effects into labor exploitation, a deeper analysis of the effects of the Swedish model on THB victimization, and an expansion of educational access and support to marginalized communities to reduce the supply of THB victims to traffickers. The output in Table 3 is particularly useful in both a) demonstrating the statistical and practical effect that THB supply factors can have on the scale of observed (sex) trafficking, and b) demonstrating that policymakers should place careful attention on marginalized communities at higher risk of THB. This is acknowledged by the European Parliament which, in a 2022 resolution, declared that educational opportunities and educational inclusion of Roma children is critical to improving the employability, health outcomes, and reduced segregation and discrimination of Roma residents and citizens (European Parliament, 2022). While this paper focused on how higher rates of educational attainment among the Roma community may lower THB for the purpose of sexual exploitation, future studies should evaluate if disparate educational attainment rates within EU member states and between member states is also having a practically and statistically significant effect on the size of THB victimization.

5.2 Ramifications for research on other “hidden” phenomena

The employment of matching methods in this paper can act as a guide for other comparative politics and legal studies which wish to establish causal links between relevant policy areas and hidden phenomena, such as illegal migration, corruption, or clientelism. Datasets that aggregate proxies for the hidden phenomena outcomes, or turn to non-traditional measurement sources like individual ministry reports and NGOs, to the country-year level and seek to evaluate how binary policy differences across countries influence such outcomes would benefit from considering the use of matching methods in their analysis. The combination of exact matching methods and the construction of a new dataset on a hidden topic (THB victimization) that required parsing through the transparency and accountability of data collection by government and non-state actors is therefore a blueprint for how other policy studies on hard-to-define subjects can be approached from a quantitative perspective. Particularly since natural experiments and randomized experiments are more challenging to come across or conduct with these “slippery” topics in comparative politics, larger discussions about how original datasets can be built to operationalize these features in their observed outcomes is called for.

6 Conclusion

Based on this study’s analysis, EU policymakers should consider the implications of legalizing the purchase of sex on THB when designing prostitution policies, and the consequences of educational disparities and the marginalization of certain ethnic communities when making decisions on anti-THB policies. The research also suggests EU policymakers should work across member states to prevent “underground” trafficking and establish robust national rapporteurs and referral mechanisms. Using exact matching data pre-processing with OLS regressions, a positive link is established between legalized prostitution and upticks in observed sexual and labor exploitation THB victimization. I also provide the first quantitative test of the link between “push” factors like educational attainment rates among the Roma community on observed THB victimization using a causal mechanism such as exact matching. The evidence in this last test implies that increasing Roma educational attainment can dramatically reduce THB for the purpose of sexual exploitation. Prevention efforts at the source, through education and prevention campaigns, should therefore also not be discounted in fighting THB.

In designing a novel dataset on THB victimization in all twenty-seven EU member states, this paper breaks major ground in establishing how administrative data sources from government offices and NGOs can be utilized to construct empirical databases which can estimate illicit activities and outcomes. The new dataset also offers opportunities for future studies to elucidate further inferences as to how specific victim protection, assistance, and integration projects affect latent THB victimization. The dataset goes beyond the Counter Trafficking Data Collaborative’s (CTDC) THB victims data and is more robust and transparent than the UNODC’s unreliable victims’ data. And in demonstrating that matching methods is applicable to THB research, this paper can become a model for blocked experiments on THB and other policy realms related to crime and migration. Finally, the importance of national rapporteurs in the EU are reiterated in the results section and offer hope that strengthening their offices through resource investment and EU and member state funding can tangibly change the situation of THB on the ground through evidence-based assessments and policy recommendations.

Notes

Villacampa, Gómez, and Torres’ (2023) dataset was also not available at the time of data collection for this project in 2021. For consistency in data collection, I could not use figures estimated by an academic study for one member state and not for others, which is problematic given how rare such academic and quantitative approximations are on observed THB victimization at the country level. Moreover, it is unclear if these authors found victimization metrics which were much larger than CITCO’s due to likely potentialities that some of the authorities sampled worked with or came across the same victims.

Robustness checks with the UNODC dataset (employing the same matched OLS regressions) and without country fixed effects confirmed these results. Robustness checks with the UNODC data (employing the same matched OLS regressions) and with country fixed effects confirmed these results in the legalized prostitution models.

Robustness checks with UNODC data (and employing the same matched OLS regressions) confirmed these results.

References

ABbilgi Merkezl. (2021). Swedish model as an example to prevent human trafficking. Retrieved June 22, from 2021 https://www.abbilgi.eu/en/swedish-model-as-an-example-to-prevent-human-trafficking.html#:~:text=In%201998%2C%20the%20Swedish%20Government,as%20well20as%20in%20Sweden

Age of Consent. (2021). Legal ages of consent by country in Europe. Retrieved July 16, from 2021. https://www.ageofconsent.net/continent/europe

Andreas, B. (2008). Forced labor and trafficking in Europe: how people are trapped in, live through and come out. In ILO working paper #57. PDF.

Baltic News Network. (July 1, 2020). Illegal prostitution to no longer be punished in Latvia as of 1 July. Retrieved July 14, from 2021 https://bnn-news.com/illegal-prostitution-to-no-longer-be-punished-in-latvia-asof-1-july-214846

Bowersox, Z. (Forthcoming). Union density and human trafficking: Can organized labor deter traffickers?. Journal of Human Trafficking.

Bowersox, Z. (2018). Natural disasters and human trafficking: Do disasters affect state anti-trafficking performance? International Migration, 56(1), 96–212.

Boyle, G., & Shields, L. (2018). Modern slavery and Women’s economic empowerment: Discussion document. London: DFID Work and Opportunities Programme. Retrieved July 13, from 2021 https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/726283/modern-slavery-womens-economic-empowerment.pdf

Brants, C. (1998). The fine art of regulated tolerance: Prostitution in Amsterdam. Journal of Law and Society, 25(4), 621–635.

Business Insider. (2019). Prostitution is legal in countries across Europe, but it’s nothing like what you think. Retrieved June 23, from 2021 https://www.businessinsider.com/prostitution-is-legal-incountries-across-europe-photos-2019-3?r=US&IR=T

Carabott, S. (2019). Prostitution: Let’s learn lessons from other places. Times of Malta. Retrieved April 20, from 2021 https://timesofmalta.com/articles/view/prostitution-lets-learn-lessons-fromother-places.753889

Cho, S.-Y. (2016). Liberal coercion? Prostitution, human trafficking and policy. European Journal of Law and Economics, 41, 321–348.

Cho, S. Y., Dreher, A., & Neumayer, E. (2013). Does legalized prostitution increase human trafficking? World Development, 41(1), 67–82.

Cho, S.-Y., Dreher, A., & Neumayer, E. (2014). The determinants of anti-trafficking policies: Evidence from a New Index. Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 116(2), 429–454.

Clarke, A., & Østerby, N. (2016). Red light, grey zone: Perceptions of prostitution vary wildly on the streets of the capital. CPH Post. Retrieved April 20, from 2021 https://cphpost.dk/?p=46057#:~:text=Prostitution%20has%20been%20legal%20in,broth_el%20or%20to%20procure%20sex.&text=Since%20Norway%20passed%20a%20law,as__20'the%20Nordic%20Brothel

CMM. (2021). What is the center against trafficking in human beings? Retrieved June 22, from 2021 https://www.cmm.dk/om-os/hvad-er-center-mod-menneskehandel

Coalition Against Trafficking in Women Australia. (2017). Demand change: Understanding the Nordic approach to prostitution. Australia: CATWA. Retrieved July 14, from 2021 https://www.catwa.org.au/wpcontent/uploads/2017/03/NORDIC-MODEL-2017-booklet-FINAL-single-page.pdf

Cockbain, E., & Bowers, K. (2019). Human trafficking for sex, labour and domestic servitude: How do key trafficking types compare and what are their predictors? Crime, Law and Social Change, 72, 9–34.

Cockbain, E., Bowers, K., & Dimitrova, G. (2018). Human trafficking for labour exploitation: The results of a two-phase systematic review mapping the European evidence base and synthesizing key scientific research evidence. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 14, 319–360.

Cockbain, E., & Kleemans, E. R. (2019). Innovations in empirical research into human trafficking: Introduction to the special edition. Crime, Law and Social Change, 72, 1–7.

Crowdhurst, I., & Skilbrei, M.-L. (2022). Swedish, Nordic, European: The journey of a model’ to abolish prostitution. In M. J. Christensen, K. Lohne, & H. Magnus (Eds.), Nordic criminal justice in a global context. London: Routledge.

Danna, D. (2014). Report on prostitution laws in the European Union. Amsterdam: La Strada International. Retrieved April 20, from 2021 https://documentation.lastradainternational.org/lsidocs/3048-EU-prostitution-laws.pdf

David, F., Bryant, K., & Larsen, J. J. (2019). Migrants and their vulnerability to human trafficking, modern slavery and forced labor. Geneva: IOM.

Davies, J., & Ollus, N. (2019). Labour exploitation as corporate crime and harm: Outsourcing responsibility in food production and cleaning services supply chains. Crime, Law and Social Change, 72, 87–106.

Davy, D. (2016). Anti–human trafficking interventions: How do we know if they are working?”. American Journal of Evaluation, 37(4), 486–504.

Dimitrova K., Ivanova S., Alexandrova Y. (2015) Child trafficking among Vulnerable Roma Communities: Results of Country Studies in Austria, Bulgaria, Greece, Italy, Hungary, Romania and Slovakia. Sofia: Center for the Study of Democracy.

European Commission. (2020). Report from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council: Third report on the progress made in the fight against trafficking in human beings (2020) as required under Article 20 of Directive 2011/36/EU _on preventing and combating trafficking in human beings and protecting its victims. Brussels: European Commission.

European Commission. (2021a). Bulgaria—5.1 Legislation. Retrieved June 22, from 2021 https://ec.europa.eu/anti-trafficking/member-states/bulgaria-51-legislation_en

European Commission. (2021b). National rapporteurs and/or equivalent mechanisms: Belgium. Retrieved June 22, from 2021 https://ec.europa.eu/anti-trafficking/national-rapporteurs/belgium_en

European Commission. (2021c). National rapporteurs and/or equivalent mechanisms: Estonia. Retrieved June 22, from 2021 https://ec.europa.eu/anti-trafficking/national-rapporteurs/estonia_en

European Commission. (2021d). National rapporteurs and/or equivalent mechanisms: Finland. Retrieved June 16, from 2021 https://ec.europa.eu/anti-trafficking/national-rapporteurs/finland_en

European Commission. (2021e). National rapporteurs and/or equivalent mechanisms: Greece. Retrieved June 16, from 2021 https://ec.europa.eu/anti-trafficking/national-rapporteurs/greece_en

European Commission. (2021f). National rapporteurs and/or equivalent mechanisms: Hungary. Retrieved June 22, from 2021 https://ec.europa.eu/anti-trafficking/national-rapporteurs/hungary_en

European Commission. (2021g). National rapporteurs and/or equivalent mechanisms: Lithuania. Retrieved June 16, from 2021 https://ec.europa.eu/anti-trafficking/national-rapporteurs/lithuania_en

European Commission. (2021h). National rapporteurs and/or equivalent mechanisms: Netherlands. Retrieved June 22, from 2021 https://ec.europa.eu/anti-trafficking/national-rapporteurs/netherlands_en

European Commission. (2021i) National rapporteurs and/or equivalent mechanisms: Portugal. Retrieved June 22, from 2021 https://ec.europa.eu/anti-trafficking/national-rapporteurs/portugal_en

European Commission. (2021j). National rapporteurs and/or equivalent mechanisms: Romania. Retrieved June 22, from 2021 https://ec.europa.eu/anti-trafficking/national-rapporteurs/romania_en

European Commission. (2021k). National rapporteurs and/or Equivalent Mechanisms: Slovakia. Retrieved June 22, from 2021 https://ec.europa.eu/anti-trafficking/national-rapporteurs/slovakia_en

European Commission. (2021l). National rapporteurs and/or equivalent mechanisms: Slovenia. Retrieved June 22, from 2021 https://ec.europa.eu/anti-trafficking/national-rapporteurs/slovenia_en

European Commission. (2021m). Together against trafficking in human beings: Ireland. Retrieved April 19, from 2021 https://ec.europa.eu/anti-trafficking/member-states/Ireland.

European Commission. (2021n). Schengen area. Retrieved July 12, from 2021 https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/what-wedo/policies/borders-and-visas/schengen_en.

Ekberg, G. (2004). The Swedish law that prohibits the purchase of sexual services: Best practices for prevention of prostitution and trafficking in human beings”. Violence against Women, 10(10), 1187–1218.

European Parliament. (2022). Resolution 2022/2662: Situation of Roma people living in settlements in the EU.” Brussels: European Commission. Retrieved April 16, from 2023 https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-9-2022-0343_EN.html

European Parliament and the European Council. (2011). Directive 2011/36/EU on preventing and combating trafficking in human beings and protecting its victims, and replacing Council Framework Decision 2002/629/JHA.” Official Journal of the European Union L 101.

European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. (2011). Survey on discrimination and social exclusion of Roma in EU. Retrieved July 17, from 2021 https://fra.europa.eu/en/publications-and-resources/data-and-maps/survey-discrimination-and-social-exclusion-roma-eu-2011

European Roma Rights Centre (ERRC). (2014). Romani children in Europe—The facts. Retrieved August 31, from 2022 http://www.errc.org/uploads/upload_en/file/factsheet-on-romani-children-in-europe-english.pdf

Eurostat. (2021a). Regional disparities in employment rates (NUTS level 2, NUTS level 3). Retrieved April 20, from 2021 https://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=lfst_r_lmder&lang=en

Eurostat. (2021b). Regional disparities in gender employment gap (NUTS level 2). Retrieved April 20, from 2021 https://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=lfst_r_lmdgeg&lang=en

Eurostat. (2021c). People at risk of poverty or social exclusion. Retrieved April 20, from 2021 https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/sdg_01_10/default/table?lang=en

Eurostat. (2021d). Population by educational attainment level, sex and age (%).Retrieved July 17, from 2021 https://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=edat_lfs_9903&lang=en

Frank, R. W. (2013) Human trafficking indicators, 2000–2011: A new dataset. Harvard dataverse, V1, UNF: 5: ueeoYxJuf05BC43+aJYBvg==[fileUNF]. Retrieved March 24, from 2021.

Frank, R. W. (2013). Human trafficking indicators, 2000–2011: A new dataset. Harvard Dataverse, V1, UNF: 5: ueeoYxJuf05BC43+aJYBvg==[fileUNF]. Retrieved March 24, 2021.

Friesendorf, C. (2007). Pathologies of security governance: Efforts against human trafficking in Europe. Security Dialogue, 38(3), 379–402.

Greifer, N. (2021). MatchIt: getting started. The Comprehensive R Archive Network. Retrieved July 4, from 2021 https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/MatchIt/vignettes/MatchIt.html?fbclid=IwAR0NijH77odFrGtxicUIRznCkOqgMTOFL2RJAkZFB5ewx2iu9q8yCaHW_ZY#assessing-the-quality-of-matches

GRETA. (2016a). Report concerning the implementation of the Council of Europe Convention on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings by Bulgaria: Second Evaluation Round. Strasbourg: Council of Europe – Group of Experts on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings.

GRETA. (2016b). Report concerning the implementation of the Council of Europe Convention on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings by Romania: Second Evaluation Round. Strasbourg: Council of Europe—Group of Experts on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings.

GRETA. (2017a) Report concerning the implementation of the Council of Europe Convention on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings by Malta: Second Evaluation Report. Strasbourg, France: Council of Europe—Group of Experts on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings.

GRETA. (2017b). Report concerning the implementation of the Council of Europe Convention on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings by Latvia: Second Evaluation Round. Strasbourg: Council of Europe—Group of Experts on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings.

GRETA. (2017c). Report concerning the implementation of the Council of Europe Convention on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings by Ireland: Second Evaluation Round. Strasbourg: Council of Europe—Group of Experts on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings.

GRETA. (2017d). Report concerning the implementation of the Council of Europe Convention on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings by Greece: First evaluation round. Strasbourg, France: Council of Europe—Group of Experts on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings.

GRETA. (2017e). Report concerning the implementation of the Council of Europe Convention on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings by Belgium: Second evaluation round. Strasbourg: Council of Europe—Group of Experts on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings.

GRETA. (2017f). Report concerning the implementation of the Council of Europe Convention on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings by Poland. Strasbourg: Council of Europe—Group of Experts on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings.

GRETA. (2018a). Report concerning the implementation of the Council of Europe Convention on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings by Slovenia: Second Evaluation Round. Strasbourg, France: Council of Europe – Group of Experts on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings.

GRETA. (2018b). Report concerning the implementation of the Council of Europe Convention on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings by Sweden: Second Evaluation Round. Strasbourg: Council of Europe—Group of Experts on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings.

GRETA. (2018c). Report concerning the implementation of the Council of Europe Convention on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings by Estonia. Strasbourg: Council of Europe—Group of Experts on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings.

GRETA. (2018d). Report concerning the implementation of the Council of Europe Convention on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings by Spain: Second Evaluation Round. Strasbourg: Council of Europe – Group of Experts on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings.

GRETA. (2018e). Report concerning the implementation of the Council of Europe Convention on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings by the Netherlands: Second Evaluation Round. Strasbourg, France: Council of Europe—Group of Experts on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings.

GRETA. (2018f). Report concerning the implementation of the Council of Europe Convention on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings by Luxembourg. Strasbourg: Council of Europe—Group of Experts on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings.

GRETA. (2019a). Report concerning the implementation of the Council of Europe Convention on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings by Italy: Second Evaluation Round. Strasbourg: Council of Europe—Group of Experts on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings.

GRETA. (2019b). Report concerning the implementation of the Council of Europe Convention on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings by Finland: Second Evaluation Round. Strasbourg, France: Council of Europe—Group of Experts on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings.

GRETA. (2019c). Report concerning the implementation of the Council of Europe Convention on Action against Trafficking in Human Being by Lithuania: Second Evaluation Round. Strasbourg, France: Council of Europe—Group of Experts on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings.

GRETA. (2019d). Report concerning the implementation of the Council of Europe Convention on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings by Hungary: Second Evaluation Round. Strasbourg: Council of Europe—Group of Experts on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings.

GRETA. (2020a). Report concerning the implementation of the Council of Europe Convention on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings by the Czech Republic: First evaluation round. Strasbourg, France: Council of Europe—Group of Experts on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings.

GRETA. (2020b). Evaluation Report Austria: Third evaluation round. Strasbourg, France: Council of Europe—Group of Experts on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings.

GRETA. (2020c). Evaluation Report Slovak Republic: Third evaluation round. Strasbourg, France: Council of Europe—Group of Experts on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings.

GRETA. (2020d). Evaluation Report Cyprus: Third evaluation round. Strasbourg, France: Council of Europe—Group of Experts on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings.

GRETA. (2020e). Evaluation report Croatia: Third evaluation round. Strasbourg: Council of Europe—Group of Experts on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings.

GRETA. (2021). Evaluation report Denmark: Third evaluation round. Strasbourg, France: Council of Europe—Group of Experts on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings.

Ho, D. E., Imai, K., King, G., & Stuart, E. A. (2007). Matching as nonparametric preprocessing for reducing model dependence in parametric causal inference. Political Analysis, 15, 199–236.

Ho, D. E., Imai, K., King, G., & Stuart, E. A. (2011). MatchIt: Nonparametric preprocessing for parametric causal inference. Journal of Statistical Software, 42(8), 1–28.

Huisman, W., & Kleemans, E. R. (2014). The challenges of fighting sex trafficking in the legalized prostitution market of the Netherlands. Crime, Law and Social Change, 61, 215–228.

Huisman, W., & Nelen, H. (2014). The lost art of regulated tolerance? Fifteen years of regulation vices in Amsterdam. Journal of Law and Society, 41(4), 604–626.

Human Thread Foundation. (2019). The Governments of France and Sweden have just announced their joint decision to develop a common strategy for combatting human trafficking for sexual exploitation in Europe and globally. Retrieved July 14, from 2021 https://humanthreadfoundation.org/france-and-sweden-join-forces-to-support-nordic-model-across-europe/

ICRSE. (2020). Hungary: Current situation of sex work in the country. Retrieved June 23, from 2021 https://www.sexworkeurope.org/news/news-region/hungary-current-situation-sex-work-country

ILO. (2014). Profits and poverty: The economics of forced labor. Geneva: ILO. Retrieved July 21, from 2021 https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_norm/---declaration/documents/publication/wcms_243391.pdf

International Centre for Migration Policy Development. (2009). Legislation and the situation concerning trafficking in human beings for the purpose of sexual exploitation in EU member states. Vienna: International Centre for Migration Policy Development (ICMPD).

Ivanov, A., Collins, M., Gorsu, C., Kling, J., Milcher, S., O’Higgins, N., Slay, B., & Zhelyazkova, A. (2006) At risk: Roma and the displaced in Southeast Europe. Bratislava: UNDP.

Jakobsson, N., & Kotsadam, A. (2013). The law and economics of international sex slavery: Prostitution laws and trafficking for sexual exploitation. European Journal of Law and Economics, 35, 87–101.

Jiang, B., & LaFree, G. (2017). Social control, trade openness and human trafficking. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 33, 887–913.

Jovanovic, J. (2015) ‘Vulnerability of Roma’ in policy discourse on combatting trafficking in human beings in Serbia. Budapest: Center for Policy Studies at the Central European University. Retrieved April 12, from 2021 http://archive.ceu.hu/sites/default/files/publications/cps-working-paper-osi-ttf-vulnerability-of-roma-2015.pdf

Kathimerini Cyprus. (2020). Bill criminalises prostitution in Cyprus. Kathimerini Cyprus. Retrieved April 20, from 2021 https://knews.kathimerini.com.cy/en/news/bill-criminalises-prostitution-in-cyprus

Kelly, E. (2002). Journeys of jeopardy: A review of research on trafficking in women and children in Europe. London: IOM. Retrieved July 12, from 2021a https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/mrs_11_2002.pdf

King, G. (2020). 16. Matching methods. YouTube. Retrieved July 15, from 2021 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tvMyjDi4dyg&t=1858s

Kingston, S., & Thomas, T. (2019). No model in practice: A ‘Nordic model’ to respond to prostitution? Crime, Law and Social Change, 71, 423–439.

Levy, J., & Jakobsson, P. (2014). Sweden’s abolitionist discourse and law: Effects on the dynamics of Swedish sex work and on the lives of Sweden’s sex workers. Criminology & Criminal Justice, 14(5), 593–607.

McCarthy, N. (2018). The legal status of prostitution across Europe. Statista. Retrieved April 20, from 2021 https://www.statista.com/chart/16090/policy-models-regarding-prostitution-in-the-eu/#:~:text=In%20many%20several%20European%20countries,seller%20and%20buyer_20are%20sanctioned

Mulvihill, L. (2017). ‘Nordic model’ adopted in Ireland. University College Cork Express. Retrieved June 23, from 2021 https://uccexpress.ie/nordic-model-adopted-in-ireland/

Myria. (2021). About Myria. Retrieved June 22, from 2021 https://www.myria.be/en/about-myria#:~:text=On%201%20September%202014%2C%20the,powers%20to%20take%20legal%20action

Nationaal Rapporteur Mensenhandel en Seksueel Geweld tegen Kinderen. (2020). Slachtoffermonitor mensenhandel 2015–2019. The Hague, Netherlands: Nationaal Rapporteur. NCCTHB. 2021. About us. Retrieved June 22, from 2021 https://antitraffic.government.bg/bg/about#about

Nordic Model Now. (2021). What is the Nordic Model? Retrieved April 20, from 2021 https://nordicmodelnow.org/what-is-the-nordic-model/

NSWP. (2017) Greek sex workers Organise conference and demand law reform. Retrieved June 23, from 2021 https://www.nswp.org/news/greek-sex-workers-organise-conference-and-demand-law-reform

O’Sullivan, F. (2013). France has just made buying sex illegal, and the rest of the continent will be watching.” Bloomberg CityLab. Retrieved June 23, from 2021 https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2013-12-05/across-europe-a-growing-sense-that-legalized-prostitution-isn-t-working

Ollus, N., Jokinen, A., & Joutsen, M. (2013). Exploitation of migrant workers in Finland, Sweden, Estonia and Lithuania: Uncovering the links between recruitment, irregular employment practices and labour trafficking. Helsinski: European Institute for Crime Prevention and Control.

Pantea, M.-C. (2006). Challenges regarding the combating of Roma Child Labor via Education in Romania and the Need for Child-centered Roma Policies. Central European University Center for Policy Studies.

Paraskevas, A., & Brookes, M. (2018). Nodes, guardians and signs: Raising barriers to human trafficking in the tourism industry. Tourism Management, 67, 147–156.

Post, C., Brouwer, J. G., & Vols, M. (2019). Regulation of prostitution in the Netherlands: Liberal dream or growing repression? European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research, 25, 99–118.

Radačić, I., & Pajnik, M. (2018). Prostitution in Croatia and Slovenia: Sex workers Experiences. Druš. Istraž. Zagreb, 27(2), 365–370.

Reinboth, S., N. Woolley (2014). Customers’ responsibility when buying sex. Helsinki Times. Retrieved April 20, from 2021 https://www.helsinkitimes.fi/finland/finland-news/domestic/11941-customers-responsibility-when-buying-sex.html

Republic of Latvia Cabinet. (2008). Regulation No. 32. Retrieved June 23, from 2021 https://likumi.lv/ta/en/en/id/169772-regulations-regarding-restriction-of-prostitution

SIPRI. (2021) Financial value of the global arms trade. Retrieved July 12, from 2021 https://www.sipri.org/databases/financial-value-global-arms-trade

Socialstyrelsen. (2004). Prostitution in Sweden 2003—Knowledge, beliefs and attitudes of key informants. Stockholm: Socialstyrelsen.

The Ministry of the Interior of the Czech Republic. (2021). Czech presidency of the EU: Joint analysis, joint action. Retrieved June 16, from 2021 https://www.mvcr.cz/mvcren/article/czech-republic.aspx

U.S. Department of State (2020). 2020 trafficking in persons report: Italy. Retrieved April 19, from 2021b https://www.state.gov/reports/2020-trafficking-in-persons-report/italy/

UNICEF. (2011). The right of Roma children to education. Position paper. Geneva: UNICEF.

UNODC. (2009). Global report on trafficking in persons. Vienna: UNODC. Retrieved July 12, from 2021 https://www.unodc.org/documents/Global_Report_on_TIP.pdf

UNODC. (2014). Global report on trafficking in persons. Vienna: UNODC. Retrieved July 16, from 2021 https://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/glotip/GLOTIP_2014_full_report.pdf

van Meeteren, M., & Wiering, E. (2019). Labour trafficking in Chinese restaurants in the Netherlands and the role of Dutch immigration policies. A qualitative analysis of investigative case files. Crime, Law and Social Change, 72, 107–124.

Villacampa, C. (2022). Challenges in assisting Labour trafficking and exploitation victims in Spain. International Journal of Law, Crime and Justice, 71, 100563.

Villacampa, C., Gómez, M. J., & Torres, C. (2023). Trafficking in human beings in Spain: What do the data on detected victims tell us? European Journal of Criminology, 20(1), 161–184.

Vuolajärvi, N. (2019). Governing in the name of caring: The Nordic model of prostitution and its punitive consequences for migrants who sell sex. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 16, 151–165.

Wagenaar, H., Amesberger, H., S. Altink (2017) The national governance of prostitution: Political rationality and the politics of discourse. In Designing prostitution policy: Intention and reality in regulating the sex trade. Bristol: Bristol University Press.

Weitzer, R. (2015). Researching prostitution and sex trafficking comparatively. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 12, 81–91.

World Bank Development Indicators. (2021a). GDP per capita (constant 2010 US$). Retrieved July 17, from 2021 https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.KD

World Bank Development Indicators. (2021b) Inflation, GDP deflator (annual %). Retrieved July 17, from 2021 https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.DEFL.KD.ZG

Zeegers, N., & Althoff, M. (2015). Regulating human trafficking by prostitution policy? European Journal of Comparative Law and Governance, 2, 351–378.

Acknowledgements

Thank you Zack Bowersox for your immense support and guidance throughout this project. There are also dozens of people I owe my gratitude to at the LSE for their help as I crafted this policy project and now academic publication, including Valerie Belu, Chris Anderson, Andrew Moles, and Toon Van Overbeke. Thank you to the ministry officials and NGO workers who meticulously record data on trafficking victims, and were willing to share their data for the creation of my original dataset. And a heartfelt thanks to the reviewers who helped make this manuscript better. I would also like to express my gratitude to Bocconi University for providing open access to this article.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università Commerciale Luigi Bocconi within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix A: THB victims data collection methodology

In an effort to rectify the lack of data on THB victims in EU member states in databases like those compiled by the UNODC and Counter Trafficking Data Collective (CTDC), I undertook the task of looking through each national rapporteur or equivalent mechanism’s online annual reports and reporting of their registered/identified victims’ metrics. In instances where the annual reports were not publicly accessible via ministry or rapporteur webpages, or there appeared to be older reports that were not online, I directly contacted the relevant officials for access to the anonymized, aggregated data on THB victims registered in the member state per year, and by type of exploitation. Following the layout of the CTDC’s global dataset, which was aggregated to the country-year level by Bowersox (Forthcoming), I collected data on the number of trafficking victims that experienced sexual exploitation, forced labour, forced labour and sexual exploitation, forced marriage, organ removal, or other types of exploitation. Detailed below are the steps I took in collecting and aggregating the THB victims’ data from each member state.

Austria

The annual reports and victims’ data were sourced from LEFÖ, a victims’ assistance NGO that is contracted out by Austria’s Ministry of the Interior to provide services to recognised trafficking victims. The total number of THB victims was provided for each year, as well as a percentage breakdown by type of exploitation. The researcher approximated the number of victims as close as possible using the percentages information, but for 2017 the rounding was slightly off. Data on forced labour victims only became available beginning with the 2014 reports. Domestic servitude was classified under the ‘other types of exploitation’ (other) category.

Belgium

The victims data were found in MYRIA’s annual reports. MYRIA is Belgium’s national rapporteur and is the state’s Federal Migration Centre. Forced criminality and forced begging were classified under ‘other’. The data on the quantity of victims registered by type of exploitation is collected by the Public Prosecutor’s office and then supplied to MYRIA. If the number of victims registered in a given year changed in later reports (since many reports listed statistics for multiple years), then the data provided in the most recent report were used and entered in the data collection process.

Bulgaria

The data on the quantity of THB victims identified in Bulgaria for the years 2013 and 2018–2020 were sourced from the National Commission for Combating Trafficking in Human Beings’ (NCCTHB) annual reports. The NCCTHB is Bulgaria’s national rapporteur. Data for the years 2014–2017 was sourced directly from Bulgaria’s webpage on the European Commission “Together Against Trafficking in Human Beings” website. The statistics listed on the European Commission webpage matched those published in later annual reports from the NCCTHB, and were most likely supplied directly to the European Commission by NCCTHB. There were two types of victims data provided in the NCCTHB’s annual reports—those supplied by the public prosecutor’s office and those supplied by ANCTHB on the number of trafficking ‘signals’ received. For consistency and to overlap with what was reported to the European Commission for the years 2014–2017, the data recorded by the public prosecutor’s office were included in this study.

Victims that were classified as having experienced domestic servitude and the selling of their newborn babies were categorised under ‘other’.

Croatia