Abstract

Consumer protection shifts risks from consumers to businesses. This raises marginal costs and equilibrium prices. It is justified when markets are not strong enough to allocate contractual risks or accident risks efficiently, especially in cases of severe asymmetric information between suppliers and consumers. Consumer protection can then increase the consumer’s expected welfare from a contract. We test these considerations in a theoretical and empirical study on consumers' right to early repayment of mortgage loans without damage compensation to the creditor in the European Union. We show in a formal model that such a right can lead to an impairment of consumer welfare, compared with the traditional rule of expectation damages for breach of contract. This applies if the consumer is risk averse and repays a loan with a high interest rate in a low interest period to take up a new loan for the same project at lower interests. From a theoretical point of view, this right has no solid economic underpinning, if it is not restricted to cases of personal hardship of the consumer and serves an insurance purpose. We present empirical evidence supporting this argument. In a panel study on monthly mortgage interest rates of 23 EU Member States between 2005 and 2017 we show how interest rate spreads change with the level of consumer protection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In this paper we present a theoretical and empirical analysis of different consumer protection rules in the European Union in case of the premature repayment of a mortgage credit. We focus on how a right to prematurely repay a long-term fixed interest consumer credit without paying any or only a capped damage compensation to the creditor affects consumer welfare. Our contribution is twofold. Our analysis of the effects of consumers' right to early repayment on European mortgage markets and mortgage interest rates is novel and points to adverse effects. If this consumer protection allows debtors to repay their long-term fixed interest rate credit after interest rates fall but before the contract ends, the debtor can take out a new loan at a lower interest rate and makes a windfall profit as a consequence of the protection. For risk averse debtors this can lead to less consumer welfare compared with the consumer welfare under the traditional contract law rule of expectation damages for breach of contract. We show, that this adverse effect can outweigh the benevolent insurance function of this right. This insurance function of the right exists, if after contract conclusion but before the contract ends the real estate is not needed anymore for consumption and goes on sale, because the consumer or somebody in her household dies, gets a divorce, moves to another city or in general if the real estate is not any longer beneficial to the consumer, because a personal risk of live materializes. To avoid high damage compensation in such a case the consumer is typically willing to pay the necessary mark up on the interest rate, which must be higher than under a rule of expectation damages for breach of contract. The typical consumer has however no willingness to pay for the costs of a mandatory rule, which entitles her to replace an old high interest rate credit by a new low interest rate credit.

Second, we analyze in an empirical cross-country study on European mortgage markets with data for 23 EU Member States from 2005 to 2017 how the different national consumer protection laws affect mortgage interest lending rates, and interest rate spreads. The starting point for our empirical study is a comprehensive comparative law research on the different levels of protection for early repayments in the EU Member States (see Sect. 4). Based on this data we construct a consumer protection index for early repayments in different EU Member States (see Table 4). The index classifies all Member States in three categories according to the kind of compensation, if any, that consumers must pay to their lenders if they decide to repay their mortgages before the contractual due date. The level of consumer protection is not uniform under EU Law. The Mortgage Credit Directive (European Parliament & Council, 2014) is on this dimension a skeleton law, which gives discretion to Member States to legally entitle their national banks to either negotiate a price for the premature ending of the credit contract, or charge full expectation damages, or to allow early repayment without any damage compensation, or to cap the damage award. The latter includes legal regimes, in which the bank can only charge additional administrative expenses incurred by early repayments. Among others, Italy, France and Spain have a high level of consumer protection, Germany and (before Brexit) the UK had a low level with an expectation damages rule. We show that a rule of no compensation has adverse effects, which can reduce consumer welfare in comparison with the rule of expectation damages, provided consumers are risk averse.

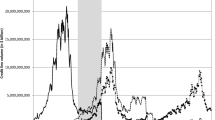

In line with our theoretical findings, our empirical results indicate that the expected costs of consumer protection are passed on to consumers via the interest rate spread, that is the difference between the lending and the refinancing interest rate of mortgage banks. They tentatively support our view that interest rate spreads increase more than proportionately with rising market interests if compensation of expectation damages for early repayments is either abolished or severely capped. In such cases the expected costs of mandatory consumer protection, which the bank passes on to the consumer, can be higher than the consumers’ willingness to pay for her protection. The paper concludes with a brief discussion of the relevance of our findings for the general design of consumer protection legislation. We try to give a tentative explanation of why a consumer protection law, which aims at increasing consumer welfare, might achieve the contrary. We conjecture that this is probably not an unintended consequence of a well-meaning law, but might follow a political dynamic along Mancur Olson’s “Logic of Collective Action” (1965).

The paper is structured as follows. In Sect. 2 we review the literature on cases where ill-designed increases in consumer protection had adverse effects for consumers. Section 3 then introduces a formal model that helps to understand whether and under what conditions a right of early repayments without damage compensation leads to an increase or decrease in consumer welfare. In Sect. 4 we present the legal regimes for premature repayments of mortgage loans in EU Member States and show how they changed over the period between 2006 and 2016. We then explain how we code the various protection levels of the EU’s Member States in a quantitative comparative law approach. In Sect. 5 we introduce our dataset and descriptive statistics. The strategy we employed to arrive at our estimations and the results of our empirical investigation are presented in Sects. 6 and 7. We conclude in Sect. 8 with a summary of how our research contributes to a better understanding and the design of consumer protection legislation.

2 Examples of consumer protection rules with adverse effects for the protected

Consumer protection rules are designed to protect the consumer in a business-to-consumer transaction. Here the consumer is typically weaker and less informed than his or her counterparty (Wulf, 2014). While the legislative intent behind consumer protection laws is to benefit the consumer, there are examples of ill-designed consumer laws that have adverse effects for the protected (e.g. Becher, 2018). One prominent example that has attracted much scholarly attention are information obligations (see e.g. Ben-Shahar and Schneider (2014) on a US context, Wulf and Seizov (2020) on an EU context). Information obligations mandate businesses to disclose certain information to consumers before they enter into a contract with them. The legislative intent behind these obligations is to offset information imbalances between consumers and businesses and thus to level the playing field between them. However, empirical evidence (Bakos et al., 2014; Ben-Shahar & Chilton, 2016) suggests that disclosures in their current form (Seizov & Wulf, 2020) rarely work as intended by the legislator. For multiple reasons, consumers choose to regularly ignore legal texts given to them by businesses (Seizov et al., 2019). These texts are too numerous, too long and their language is inaccessible. Even if consumers try, they often struggle to understand them for lack of legal literacy. They thus resort to other means of getting informed about a business or a transaction, such as reputation, quality seals or advice from friends or professional information intermediaries. Taken together, these shortcomings have led Ben-Shahar and Schneider (2014) to declare the failure of mandated disclosures altogether.

There are other cases where European consumer protection rules have adverse effects. The Consumer Sales and Guarantees Directive increased the statutory warranty for consumer purchases. Kirstein and Schäfer (2007) asked whether this leads to a market failure on the German market for used cars. They argue that before the law came into effect, voluntary contractual warranties had a signaling function that prevented market failure through adverse selection in "lemons" markets. Kirstein and Schäfer hypothesis that the newly introduced mandatory warranty disrupts this signaling function and thus provokes market failure. They find that as a result of the newly introduced warranty regime the German market for used cars split up. Used cars that were previously sold through dealers are now sold in private direct sales (which are exempted from the statutory warranty) or exported to non-EU countries. As a result, transaction costs for the cheapest cars in the market increased and the average level of warranty ownership among consumers may counter-intentionally have decreased rather than increased. Also, the market for cheap old cars, which authorized dealers bought from their customers and sold at very low prices without warranty shrunk. People with little money often preferred the low price without warranty and got cheap repairs in specialized firms which assembled second hand spare parts. These cars are now shipped to countries outside the EU.

The EU’s Consumer Sales and Guarantees Directive furthermore introduced a right for consumers to choose whether a defective good should be repaired or replaced. Eide (2009) investigates whether this right is really to the advantage of the consumer. He argues that both consumers and businesses would be better off if vendors could freely decide whether it is more economical to repair or replace a defective good. For some products, a mandatory replacement option may cause a market price increase that is higher than the increase in the consumers’ willingness to pay. Furthermore, the market price increase may be lower than the increase in the producers’ expected marginal costs. Eide concludes that it is thus questionable whether warranties at a presumably high level of consumer protection are always in the best interest of the consumers. Mandatory changes in rights and obligations among contracting parties may have distributive effects that are different from what the legislator intended.

Schäfer (1999) criticizes the EU’s Distance Selling Directive, a predecessor of the Consumer Rights Directive, for establishing a right of withdrawal for all distance purchases. He argues that this right allows buyers who regret their purchase decision to withdraw from the contract. In effect, the resulting costs (inspection, repackaging, decrease in value of returned goods, etc.) are largely charged to all other buyers. Depending on the product, these costs can be considerable and outweigh the resulting consumer benefit. Schäfer argues it would have been better to let market participants decide for themselves for which products the costly right of withdrawal provides a real consumer benefit. In another example, Schäfer (2015) describes a situation in the German jurisdiction in which trivial deviations from the legal standard of pre‐contractual information regarding the right to revocation for mortgages entitled debtors to an eternal right to revoke their credit contracts. This allowed consumers who took up a fixed interest loan when interest rates were high to pay their loans back prematurely and roll over the credit with a new one at now historically low interest rate. This practice, that was supported by consumer organizations and lower courts, would have led to double‐digit billion Euro losses for the banking industry. Schäfer concludes that this is an exaggerated form of consumer protection for which no sound economic basis does exist. It was later stopped for the same reasons by changes in the respective legislation.

In the following sections we analyze in a theoretical and empirical study whether consumers' right to an early repayment of mortgage loans without damage compensation to the creditor is another instance of a consumer protection rule with adverse effects for the protected.

3 The right to early repayment without damage payment and consumer welfare

In this section we analyze under what condition a right of a consumer to premature repayment of a mortgage credit with a fixed interest rate might lead to an increase or decrease of consumer welfare, if no damages for the breach must be paid. This right affects two future states of the world for the consumer. First, the benefit of the mortgage loan for a consumer can disappear during the loan period. The debtor might die or wish to sell the real estate for serious personal reasons such as a change in employment, a divorce, or some other change in personal circumstances, which lead to the necessity to sell the real estate and repay the loan prematurely. This is the personal risk, whose realization under the usual contract law rules triggers compensation for the expectation damages of the creditor bank. In line with the argument of Baffi and Parisi (2021) the right to premature repayment without damage compensation insures in this case a consumer against this risk for a risk premium, which becomes part of the credit costs. A risk averse consumer gains if this risk is shifted to the creditor for a price increase of the credit, which is equal to the damage of the bank from the early repayment and then increases consumer welfare. As we assume—in favor of consumer protection—throughout this paper that the credit market is not perfect enough to realize this outcome and remove the default rule of expectation damages, and that only a mandatory consumer protection rule can realize this result.

However, there exists also an adverse effect of this right. After the debtor takes up a fixed interest rate credit a right to early repayment can lead to an additional gain for the debtor if the market interest rate falls after the contract was concluded it therefore becomes profitable to repay the old loan and take out a new one at a lower interest rate for financing the same real estate. Contrast to the analysis of Baffi and Parisi (2021) we show that in this case the right to early repayment leads to a decrease of consumer welfare of risk averse consumers. This part of a right to early repayment is comparable to an option contract or a lottery, for which a risk averse person would not have the willingness to pay the premium, which allows to realize extra gains in a period of low interests.

For further analysis we assume—in support of consumer protection—that market forces are not strong enough to supply a range of different loan contracts with different interest rates for different attitudes to risk. Otherwise, there would be no rationale for a mandatory consumer protection rule as the debtor would then have free choice between different contract types with different allocations of risk and different interest rates. We proceed as follows. We first analyze the expected gains for the consumer in a competitive market and show, that under different rules in the case of early repayment the expected gain does not change. We then assume that consumers are risk averse and show that a right to early repayment might or might not increase consumer welfare depending on whether the insurance character or the lottery character of this right prevails.

3.1 The model

For simplicity we analyze one unit of credit, which is taken up for one period and repaid at the end of the period. The interest is also paid at the end of the period. The interest rate for one period is i and the benefit of the loan for the consumer is either b > 0 or 0. Without risk the net gain \((G)\) from the contract for the consumer would be \(G=b-i>0\). The mortgage bank refinances the loan with mortgage bonds with the same maturity or with similar instruments, thus avoiding any risk from maturity transformation, which is common practice of mortgage banks.Footnote 1 For convenience we assume that the opportunity cost of handling the loan is 0 for the bank. This implies that the interest rate margin between the bank’s borrowing and lending costs is also 0 for a risk-free loan and that for the risk-free contract the bank’s lending and borrowing interest rates are the same, because the bank operates in a market equilibrium, in which prices are equal to opportunity costs. This assumption avoids carrying through all formulas a positive constant mark up for an interest rate spread, which covers handling costs of the bank and the general default risk but would not add anything to clarify the analytical problem to show, that a right to early repayment without compensation of the bank’s expectation damages can reduce consumer welfare.

When concluding the contract consumers and banks know risks and chances. After conclusion of the contract the parties learn whether a personal hardship has intervened and whether and how the market interest rate is changing. The debtor learns whether the personal benefit from the contract is b or becomes 0 due to a change of personal circumstances and the debtor therefore wants to sell the real estate, which is no longer of any use to her and repay the loan. And she learns whether the market interest changes.

Let the risk-free interest rate at the time of contract formation be \({i}_{1}\) and the post-contractual market interest rate be \({i}_{2}\). If the interest rate falls after contract formation, \({i}_{1}>{i}_{2}\), the debtor has an interest in paying back the loan and taking out a new one at a lower interest rate to finance the same project. For convenience we assume that only 2 market interest rates exist, high (h) and low (l).

-

The contractual interest rate is either high or low that is \({i}_{1}={i}_{1,h} or {i}_{1}={i}_{1,l}\). The same applies for the post-contract interest rate, which is either \({i}_{2,h} or {i}_{2,l}\)

-

Let \({p}_{h }\epsilon \left(\mathrm{0,1}\right)\) be the probability that the interest rate remains the same after contract formation if it was high at the time of contracting\(({i}_{1}={i}_{1,h})\). By assumption we excluded the possibility that it further increases because only a high and a low interest rate exist. Consequently, the probability that under this condition the interest rate falls to \({i}_{2,l}\) after contract formation must be \(\left(1-{p}_{h }\right).\)

-

If at the time of contract formation, the interest rate is low \(({i}_{1}={i}_{1,l})\) the probability that after the contract the interest rate may further decline is by assumption 0. Consequently, the probability that the interest rate remains constant or increases ex post is then 1.

-

The probability of a personal hardship, which leads to the necessity to sell the real estate and repay the debt prematurely is \(q\epsilon \left(\mathrm{0,1}\right)\) at the time of contract formation.

Now assume that the contractual interest rate is high, when the contract is concluded \(\left({i}_{1}={i}_{1,h}\right).\) The parties learn immediately after concluding the contract whether the benefit of the contract is either b or 0. They also learn immediately whether the post contractual interest rate remains high or becomes low.

3.2 Analysis of the right to premature repayment without damage compensation

The debtor can then repay the loan without paying any interest, which is due at the end of the credit period. This assumption, that the credit is prematurely paid back only a logical second after the contract was concluded and that therefore no interest is due keeps the formulas simpler. It allows to work with only one period instead of working with more than one period. The bank can calculate the expected damages for the risk premium to be included in a contract with a mandatory rule allowing early repayment. In a high interest period \(({i}_{1}={i}_{1,h})\) the expected damage \(({ED}_{h}\)) of the bank from the consumers’ right of early repayment is equal to the probability that the ex post interest rate after contract formation will be low, multiplied with the difference between the high and the low interest rate. This is the bank’s loss in case of early repayment.

In the model those debtors, who pay back the credit even though the interest rate remains high after contract formation because the benefit from the contract disappears cause no damage, because the bank gets the money back and can reinvest it for the same interest by buying mortgage loans. Using the differential method of damage assessment, the damage is then \(\left({i}_{1,h}-{i}_{2,h}\right)=0.\) If handling costs of banks were not assumed to be 0, expected damages would be higher independent from interest rate changes. This part of the bank’s potential damage does, however, not contribute to clarify the proposition that, depending on interest rate changes after contract formation the right to early repayment can result in decreasing consumer welfare.

For the mark up \(({r}_{h})\) on the lending rate the expected damage must be divided by the probability that the contracts are served that is by \({p}_{h}\left(1-q\right)<1.\)

Formula 1 does not yet reflect the economically important fact that the probability that the high interest rate in the precontractual situation remains high after the contract was concluded \({(p}_{h})\) depends on the precontractual interest rate \({i}_{1,h}\) itself. Interest rates fluctuate over time and the higher the interest rate is at the time of contract formation the lower is the probability that it will remain high in the future. We therefore get

A concrete example, which meets these conditions is \({p}_{h}=\frac{1}{1+({i}_{1,h}-{i}_{1,l})}\). Inserting this into the equation for the mark up yields

This is a parabola, whose value is 0 at \({i}_{1,h}={i}_{1,l}\), and which increases more than proportionately with higher values of\({i}_{1,h}\). The first derivative of \({r}_{h}\mathrm{ with respect to} {i}_{1,h}\) is positive and the second derivative is also positive and increasing. The economic implication is that the right to early repayment leads to a risk premium of the mortgage bank, which increases with the market interest rate \(({i}_{1,h})\) for two reasons. The higher the contractual interest rate the higher is the expected loss per unit of credit caused by premature repayment in case the interest rate drops after the contract. On top of this comes an indirect effect. The probability that the debtors will repay the credit prematurely because interest rates fall in the future will also increase with the contractual interest rate, which again increases the risk premium of the bank. Both effects together care for a hyperbolic reaction of the bank’s risk premium to increasing market interests.

We now calculate the expected net gain from the contract to the consumer in the case of a right to premature repayment (Table 1).

If the consumer has the right to early repayment the expected gain from the loan (EGL) is then

Notice that in case the personal risk (q) realizes the benefit from the contract becomes 0. Then only the affected debtors will repay early, if the ex post interest rate remains high. But in the case of a decreasing interest rate all debtors will repay early. Those for whom the benefit from the contract remains b will repay early and take up a new credit at a lower interest rate. The others, for whom the personal risk has realized will also repay early. For them the gain from the contract will be 0. If the risk premium is included explicitly, we get for the expected gain from a credit contract, which was concluded during a high interest period.

After reshuffling we get

In the model a risk premium exists only for the first credit and not for the second credit. If the debtor takes up the second credit at the low interest rate (\({i}_{2l})\) the interest rate cannot—by assumption—decline any more in future. The bank cannot impose a risk premium on the second credit, because the bank has no damage if the second credit is also prematurely repaid. It reinvests the repaid loan at the same interest rate as the lending rate. In the real world it would however recover its handling costs, which are in the model assumed to be 0. This assumption avoids an infinite regress for the calculation of the risk premium without affecting the main point of the analysis. Otherwise, the calculation for the risk premium of the second contract would require the possibility of a third contract and so forth.

Now assume that the first credit is taken up not in the high interest period but in a low interest period \({i}_{1}={i}_{1,l}\). In that case the future, post contractual interest rate can by assumption not further decline. It is either unchanged or higher. Therefore, in this case the only risk of the bank is that the personal risk q realizes. But a damage cannot occur, because an early repayment allows the bank to either invest the money at the same rate or at an even higher rate. We can therefore exclude this case from further consideration. The expected gain of the debtor from the contract is then

This constellation in the model, in which the premature repayment of credit causes no damages and consequently no interest rate mark up is not further considered in the subsequent analysis.

3.3 Analysis of the rule of expectation damages for premature repayment

If the legal remedy for early repayment is expectation damages the damage from early repayment is the difference between the contractual and the post-contractual interest rate \({i}_{1}-{i}_{2}\). The bank can invest the repaid money at an interest rate of \({i}_{2}\). It can, for instance, buy mortgage bonds on the secondary market. A damage payment results if and only if \({i}_{1}>{i}_{2}\). Otherwise the differential method of damage calculation results in a damage award of zero. The compensation payment is therefore

Let us now assume that after the conclusion of the contract the market interest rate falls, but the benefit from the contract remains at b. We get an outcome which is different in comparison with the result under a right of premature repayment. The debtor wants to end the contract and take out a new mortgage at the low interest rate. With expectation damages as remedy for breach of contract her gain would be \((b-{i}_{2})-\left( {i}_{1}-{i}_{2}\right)=b-{i}_{1}\). The term in the first bracket is the consumer’s gain from the new mortgage contract and the term in the second bracket denotes the amount of damages to be paid. The early repayment motivated by the lower interest rate does not result in a gain that is higher than the gain from performance of the contract as originally concluded. Therefore, no early repayment results for taking up a new credit if interest rates decrease after contract formation (Table 2).

A rational debtor will consequently terminate the mortgage contract if and only if the post-contract benefit falls from b to 0, and not if interest rates have fallen. Under this rule the probability of early repayment is q.

Unlike in the scenario with a right to early repayment with 4 possible outcomes, here the consumer expects only three possible outcomes when concluding the contract under the rule of expectation damages.

The expected gain from the contract for the consumer is then under the rule of expectation damages

If we compare (3) and (4) we see that the expected gains from the contract with a right to premature repayment without damage compensation and alternatively with compensation of the expectation damages of the bank are the same with and without consumer protection.

If the contractual interest rate is low the post-contractual interest rate is either the same or higher. It cannot become lower. A breach of contract cannot cause any damage to the bank under the given assumption of zero handling costs. Like in the case of a right to early repayment the expected gain from the contract is then \(EG{E}_{l}=\left(b-{i}_{1,h}\right)\). This implies that the expected gains from the contract are the same under the two legal rules.

This equality reflects only that the cost of damage compensation in a competitive market is internalized in the price of the product if a breach of contract is any time possible without damage compensation. The difference between the two contracts with and without consumer protection is that without the protection the consumer repays the credit early only after being aware that a personal risk is involved, that is, if the loan loses its benefits after the conclusion of the contract. Whereas with consumer protection the consumer also repays the loan if the interest rates fall after conclusion of the contract. In the model the different rules have no effect as long as parties are risk neutral. Expected gains remain the same. Effects on consumer welfare arise only if the risk attitude of consumers and banks become different and banks are risk neutral and maximize profits, whereas consumers are risk averse. We show that under this condition the right of early repayment can increase or decrease consumer welfare in comparison with expectation damages.

3.4 Expected utility from consumer protection with risk averse consumers

That often the costs of consumer protection become part of the price and let the expected gains from the contract unchanged is well known and neither a reason for nor against consumer protection. Often the underlying rationale for consumer protection is risk spreading to the cheapest insurer or risk spreader. Consumers are risk averse. Firms are often risk neutral with regard to a single transaction and maximize profits. If consumer protection leads to insurance or risk spreading, and in a more general term to the reduction of the standard deviation of future potential gains and losses from a contract consumer protection increases consumer welfare (Consumer’s utility) even if it leaves expected contractual gains for the consumer unchanged.

We therefore compare the expected utility of loan contracts for the consumer under the two alternative legal norms. We show that even with risk averse consumers it is questionable whether shifting the risk of early repayment is associated with any additional gain for debtors. On the contrary the opposite is often likely. For a risk-averse debtor the expected benefit (utility) from the contract can be expressed by the following equation.

EU is the expected utility from the contract. EG is the expected gain and \(\sigma\) is the standard deviation of the expected gain from the contract. \(\delta\) is a parameter that defines the degree of risk-aversion. \(\delta =0\) implies risk neutrality. Expected gain and expected utility are then the same.\(\delta >0\) implies risk aversion and the absolute value of \(\delta\) denotes the level of risk aversion. It is easy to see from formula (5) that the expected utility (consumer welfare) from the contract becomes the lower the higher the standard deviation \(\left(\sigma \right) \mathrm{and the degree of risk aversion }\left(\delta \right) \mathrm{become}.\)

Following our assumptions introducing mandatory consumer protection in the form of a right to early repayment must increase consumer welfare if it insures the consumer for the expected personal risk \((q)\). In that case a risk premium on the interest, which has to be paid with certainty reduces the risk from the contract. This increases the welfare of risk-averse debtors if the expected gains remain unchanged (as we have shown). If therefore the right to early repayment reduces the risk of a damage this would increase the interest rate but eliminate the possibility of a damage. It would then leave the expected gain (EG) from the contract unchanged in relation to a rule of paying expectation damages for breach of contract as the consumer pays for the costs of the protection. But it also reduces the variance of expected gains from the contract. This increases consumer welfare. The right to early repayment would be a mandatory insurance contract, which—in the model—increases consumer welfare, if market forces are not strong enough to generate this result.

However, the right to early repayment not only protects the consumer partly against the personal risk of losing the benefit (b) from the contract and additional damage payments. It also gives him or her the chance to repay the loan and take out a cheaper one to finance the same project if interest rates fall. This part of the early repayment right forces the creditor to sell a mandatory lottery ticket together with the credit contract as part of the interest markup, which the debtor must buy to have the chance of making a windfall gain if interest rates subsequently decline. This is not a mandatory insurance but a mandatory lottery, or a mandatory option contract for which there exists no underpinning in the theory of consumer protection. This part of the early repayment right does not replace a risk with an insurance premium of equal expected value, but demands payment of the price of a lottery ticket which provides a chance of winning and the risk of losing the price for the ticket. This is the opposite of an insurance. This increases the standard deviation of the expected value of the contract and decreases the welfare of a risk averse consumer, whose willingness to pay for a lottery ticket or an option contract is lower than its cost price. It depends on parameters, whether the insurance part or the lottery part of the right of early repayment is stronger. In general, an overall adverse effect of a right to early repayment consumer protection is the more likely the lower the personal risk q is and the more interest rates change over time.

Formula (5) says therefore nothing about whether the right to early repayment increases or decreases the welfare of a risk averse consumer in comparison to the expectation damage rule for breach of contract because this right has two elements. It insures against a personal risk and thus reduces the variance from expected gains from the contract. And it provides a lottery ticket leading to a profit in case of decreasing interest rates. A risk averse consumer would in a perfect market be willing to pay the premium for the insurance but would not be willing to buy a lottery ticket for the price of the additional expected gain. The insurance reduces and the lottery increases the variance of the potential gains from the contract. Therefore, the insurance part of the right of premature repayment without damage payment increases and the option contract part of it decreases consumer welfare.

We now show the results of one set of parameters for which the right to early repayment reduces consumer welfare. As the expected gains of the consumer from a mortgage contract are the same with and without consumer protection and as we assume that consumers are risk-averse, consumer welfare increases if the standard deviation \((\sigma )\) for contracts with the right to early repayment is smaller than under the legal norm of expectation damages for breach of contract. Otherwise consumer protection reduces consumer welfare.

With parameter values \(b=10 {i}_{1,h}=\mathrm{0,05 }, {i}_{2,l}=\mathrm{0,01},{p}_{h}=0.75, q=0.1\) and a credit amount of 100 the expected gain from the contract is 4,4. The standard deviation \((\sigma )\) under a rule of compensation for expectation damages in the case of early repayment is 2,37. With a right to early repayment without expectation damages it is 4,53. This implies that in this case the right to early repayment decreases consumer welfare as defined above. The consumer welfare-increasing effect of the mandatory insurance for the personal risk (q) is smaller than the welfare-reducing effect of buying a mandatory winning chance which allows an extra gain if market interest rates should decrease after contract formation. This is not a necessary result but depends on parameters.

It follows from this analysis that the right to early repayment adds to the credit contract two contrasting elements which both lead to a mark up premium on the bank’s lending rate. The right insures the debtor against a personal risk that the benefit from the contract disappears later, which forces her not only to sell the real estate but also leads to damage compensation. If part of this risk is shifted to the bank the resulting new risk allocation leads to a mark up on the lending rate of the bank. This leaves the expected gain from the contract unaffected, but reduces the standard deviation of future gains and thus increases consumer welfare.

However, the rule also imposes the winning chance to make a bargain from decreasing future interest rates, which leads to a further mark up on the bank’s lending rate. This leaves the expected gain from the contract again unaffected but increases the variance of potential gains from the contract in comparison to the rule of expectation damages for breach of contract. The latter rule destroys any incentive to repay early and take up a new credit at a lower interest rate. This effect can outweigh the effect of the insurance element of the right to early repayment and then reduces consumer welfare, compared with a rule of expectation damage. With rising interest rates at the time of contract formation the option character of a right to early repayment becomes more important because with a higher interest rate \(({i}_{1,h})\) the probability that interests will decline after the contract was concluded is also increasing. The loss of the bank also increases the more the interest rate has declined at the time of early repayment in comparison with the contractual interest rate. High interest rates at the time of contract formation promote the lottery character of the credit contract, whereas low interest rates reduce this adverse effect.

We arrive therefore at our hypothesis, that we test empirically in the second part of our paper: the right to early repayment will increase the interest rate spread between the banks’ borrowing rate and lending rates. Drawing from our theoretical model we furthermore argue that this mark-up will increase more than proportionately with the absolute level of the real interest rate at the time of making the credit contract.

3.5 Relaxing assumptions

The above results show that the benefits from the right to early repayment are doubtful and depend on parameters. We arrived at these results with assumptions about market conditions that are most conducive to consumer protection. The case for a right to early repayment becomes even less convincing if some of these assumptions are relaxed and rendered more realistic.

-

High and low risk consumers

We regarded the personal risk that the value of the loan may be reduced to zero in the post-contract situation as equal for all debtors. This implies that with risk averse consumers a right to early repayment which removes this risk always leads to higher consumer welfare. It is, however, more likely that this risk will differ across debtors. While one debtor might still be on the job market and have a high risk of moving and selling her home, this may not apply to another debtor. One debtor may be in a stable family relationship, with a low associated risks of changing residence, while another will not. There are many reasons why risks may differ across debtors and why banks may not have the necessary information to calculate risk premiums tailored to the needs of every customer or even groups of customers. With not one but many personal risks we get \({q}_{i}\epsilon \left\{{q}_{1},\ldots {q}_{n}\right\}\).

The index number 1 denotes the debtor with the lowest risk, the index number 2 the debtor with the second lowest risk and n the debtor with the highest risk. If one assumes that the bank knows the risk distribution among its customers from past experience, but cannot identify the risk associated with individual persons upon contract conclusion it must calculate an average probability of the personal risk.

$$\overline{q} = \frac{{\mathop \sum \nolimits_{i = 1}^{n} q_{i} }}{n}$$As many scholars have previously argued, this leads to a pooled equilibrium price. All consumers whose \({q}_{i}>\overline{q }\) are subsidized by those consumers whose \({q}_{i}<\overline{q }\). This is an unfair redistribution which has a certain advantage for the high-risk types and a certain disadvantage for the low-risk types. Some of these consumers may be driven out of the market as their mortgage costs become equal to or higher than the benefit from the loan. The right of early repayment then leads to inefficient prices and quantities and therefore also to consumer welfare losses even if the problem of using the right to take up a new and cheaper credit in a low interest phase did not exist. It depends on parameters whether the low-risk types are still better off with the right to early repayment than without this right. If they are worse off it also depends on parameters, whether the right to early repayment has still a net benefit for all debtors taken together. But it certainly reduces the benefit from consumer protection compared to the above model with only one risk type.

-

Risk-averse banks

In the above model we assumed in favor of consumer protection that debtors are risk-averse, and banks are risk-neutral. This is a reasonable assumption for the allocation of the personal risk. The law of large numbers allows the bank to treat this risk as if it were a certain cost. However, in the case of the risk of early repayment this reasoning does not apply. When the post-contract interest rate falls below the pre-contract interest rate no debtor will have an incentive to end the contract under the rule of expectation damages because the personal benefit from the breach of contract is cancelled out by the damage compensation. But with a right of early repayment all debtors have the incentive to breach as it is cost free ex post. If interest rates fall sharply a mortgage bank is faced with the risk that almost all of its loans will be prematurely repaid. The law of large numbers does not apply and the bank is as vulnerable as the consumer, as it is exposed to a lump risk. Small errors in calculating the risk premium can then lead to huge losses of the bank. The consequence is that the risk premium which the risk-averse bank charges become higher than the expected value of the risk. This factor increases the cost of consumer protection for the consumers and further reduces the consumer welfare from the protection. Another consequence might be that mortgage banks try to avoid this lump risk by not offering fixed interest rate contracts any more or not for long periods.

-

Biased consumers, status quo orientation, loss aversion and probability weighing

Status quo bias: The adverse effects of this consumer protection become worse if some consumers suffer from a status quo bias and others fail to inform themselves about current interest rates and therefore make no use of the opportunity to replace an old high-interest loan by a new low-interest loan. These biased and/or uninformed debtors cross-subsidize the informed and rational consumers and make a certain loss as they pay a risk premium for nothing. The unconditional right to early repayment would therefore further reduce consumer welfare for consumers with a status quo bias, if it includes the right to repay the old high interest loan and replace it by a new low interest loan.

Loss aversion as analyzed by Kahneman and Tversky (1979) in their prospect theory can also change the results derived from the assumption of rational and risk averse consumers. Loss aversion implies that a change of the status quo, which is perceived as a loss counts more than an equally high gain. Loss aversion leads actors to a higher willingness to pay for insurance than under risk aversion. For the economic analysis of a right to early repayment this implies that under loss aversion the willingness to pay an interest rate mark up for an insurance against the realization of a personal risk is higher than under risk aversion. But the willingness to pay for a lottery ticket or an option contract as part of the credit contract is even lower than under risk aversion.

Probability weighing: Heuristic weaknesses to process probabilities are another cause of deviating from rational choice even if the decisions have to be made under risk and not under uncertainty, i.e. where probabilities are not available. Actors have a tendency to either disregard very small probabilities and setting them to zero or to overestimate them, for instance the risk of an airplane crash. And they display a tendency to underestimate higher probabilities, for instance the probability of a heart attack (Zamir & Teichman, 2018). The probabilities in our model, that is the probability that one has to sell the own house and must pay the debt prematurely and the probability that it might become profitable in the future to repay the loan prematurely and take up another credit at a lower interest rate are not small but sizeable probabilities, which many consumers might underestimate. Consequently, their willingness to pay for an insurance against the personal risk of having to sell the house might be too low as the risk is underestimated. A right to early repayment, which removes this risk, can then be regarded as a tool to correct this bias of consumers. This adds an extra argument for this right on top of the argument that a fully informed and risk averse consumer would be willing to pay the cost for this insurance. The risk averse consumer with a bias to downplay the risk does not have this willingness to pay but would regret that this right does not exist if she learned about her bias.

Equally the consumer might underestimate the probability of a windfall profit, when interest rates decline after contract formation. The willingness to pay for an option contract might then be even lower than without the bias. However, a debiasing state intervention would not lead to a right to prematurely end the contract and realize a windfall profit by taking up another credit, because a risk averse consumer without this bias would still not be willing to finance the cost of this option.

The research results of the behavioral school support the view, that a right to early repayment in case the consumer must sell her real estate because a personal risk (death, personal bankruptcy, divorce, move) improves consumer welfare. It removes a risk and transfers it against a price from the risk averse consumer to the risk neutral bank. Results from behavioral economics also either support or do not remove the finding, that a right to early repayment, which includes termination of the credit contract for taking up a new and cheaper credit must result in a decrease of consumer welfare.

4 A comparative overview of consumer's right to early repayment of mortgage loans in the European Union

To test our main hypothesis that the right to early repayment will increase the interest rate spread between the banks’ borrowing rate and lending rates in a more formal manner, we first constructed a consumer protection index. The index classifies countries according to the kind of compensation, if any, that consumers must pay to their lenders if they decide to repay their mortgages before the contractual due date. Our categorical index variable ranges from the lowest level of consumer protection “To be negotiated = 0” to the highest level of consumer protection “No charge = 2”. All categories of the index along with a detailed description are displayed in Table 3, below.

Our index classifies the regulations governing early repayment in all EU Member States between 2006 and 2016 on a month-to-month basis. To obtain information on what regulations governed early repayments at which point in time in a given country, we draw from multiple sources. A study conducted by the European Commission as part of its effort to harmonize the European mortgage markets, gathered detailed information on the national mortgage markets (Commission of the European Communities, 2007, see especially pages 55–81). From this study we have taken information on the legal regimes governing early repayments in the EU Member States in 2006. The second report is the Commission’s “Study on the Costs and Benefits of the Different Policy Options for Mortgage Credit” (European Commission, 2009, see especially “Annex B: Legal Summaries”). This study collected data on the levels of consumer protection for premature repayments in 2009. However, both reports contain mainly qualitative information on the national protection levels. We thus developed our own classification scheme to quantify these data and followed a double-blind coding procedure. Finally, in 2016 we conducted an e-mail survey to gather our own primary data. Here we asked the central banks, ministries of finance of the Member States and bank or consumer protection associations about the applicable level of consumer protection in their respective countries. The consumer protection index that resulted from our classification exercise is displayed in Table 4, below.

Based on our “Consumer Protection Index” we created two differently coded explanatory variables. These variables were used in our statistical models to test the hypothesis that more stringent consumer protection legislation leads to higher interest rate spreads between the banks’ borrowing rates and lending rates. Our first, main variable is the Consumer Protection for Early Repayment (Dummy) variable. As indicated by its name, this variable is a dummy that codes the first category of our index “Compensation for the lender must be negotiated or damages must be paid” as 0 and all other categories, i.e. “Liability cap or lender's additional administrative expenses only” and “No charge” as 1. The rationale behind this coding is that the reference category represents those countries which apply the default rule found in contract law for a breach of a consumer mortgage contract. The variable codes as 1 all countries that diverge from this default rule and instead prescribe a higher mandatory protection level for consumer mortgage contracts. This dummy is therefore a conservative and reliable measure of the consumer protection levels for early repayments in the different Member States. We use the dummy variable in our main statistical models, as we consider it to be the most appropriate measure to test our research hypothesis.

Our second variable is the Consumer Protection for Early Repayment (Categorical) variable. This categorical variable has the same coding as the consumer protection index introduced above. When compared to the dummy variable, it is the more finely grained and complex measure. From a legal point of view, the variable may be less reliable, if we consider that the multilinguistic, multijurisdictional environment of the European Union made the comparative law effort on which the coding is based a challenging task. Furthermore, the numbers of observations per category are less balanced than for the dummy variable. We therefore use this variable for a general robustness test. In any case, the results that we obtained with both variables are consistent with each other.

5 The dataset and descriptive statistics

In the previous section we introduced our main explanatory variable, the level of consumer protection. In this section, we will introduce our dependent variable and all the other variables in our dataset. See also Milani (2012), who provides a useful overview of the determinants of mortgage interest rates and European Mortgage Federation (2017) for a general overview of recent trends and developments in European mortgage markets.

Our dependent variable Interest Rates for Long-Term Consumer Mortgages is the monthly average interest rate on long-term consumer mortgage loans in each of the Member States of the European Union (European Central Bank, 2017b). The data cover long-term mortgage loans with maturities of over 5 years, and generally up to 10 years or longer. The representative national average interest rate is computed monthly (European Central Bank, 2017a).Footnote 2

To estimate the effect of consumer protection legislation on mortgage interest rates we need to control for the main factors that affect these rates: the lenders refinancing costs. Mortgage banks generally refinance their loans by issuing covered mortgage bonds. Unfortunately, national interest rates for mortgage bonds are not available for all Member States. We must therefore approximate the national refinancing costs of the lenders. We do so in two different ways. Our main benchmark for the lenders' refinancing costs, the variable Benchmark Refinancing Cost, is the interest rate for German mortgage bonds with a remaining maturity of 10 years, the so called “Hypothekenpfandbriefe”. This data is available from the “Bundesbank”, the German central bank (Deutsche Bundesbank, 2017). As an alternative benchmark for the lenders refinancing costs we use the monthly interest rate of governmental bonds with a remaining maturity of 10 years for each Member State, the variable Alternative Benchmark Refinancing Cost. The data is available from Eurostat (2017a) the statistical office of the European Union. As compared to the German mortgage bonds, the advantage of using these rates is that they are available for the Member State level. However, the disadvantage is that in contrast to mortgage bonds these financial instruments are not secured by a collateralized asset. This consideration is important for our research because the global financial crises and the European debt crisis fell within our study period. At times when the issuing government is in difficulties the market charges a sovereign default risk premium on government bonds. Such premiums are, however, not charged on covered mortgage bonds that are secured by an underlying asset (the real estate) and which thus present less of a risk to the investor. In our main models we therefore decided that German mortgage bonds are more suitable for approximating the refinancing costs of the mortgage banks and we employ government bonds only for a general robustness check.

Economic growth is another factor that may affect mortgage interest rates and we control for it using the variable Real GDP Growth Rate. We obtain our real GDP growth data from Eurostat (2017d). To ease the visibility of the variable's coefficient for the reader, which otherwise becomes almost zero, we scaled the variable down by a factor of ten. All other things being equal, in times of expanding economies the demand for money increases and thus interest rates are expected to rise. Conversely, declining GDPs should lead to a decrease in interest rates. As a robustness test we replace our GDP growth rate variable with a proxy for the size of a country’s financial sector, the variable Size of the Financial Sector. To estimate this we use data from the The World Bank (2017b) on financial resources provided to the private sector by financial corporations as percentage of GDP. To obtain a proxy for the size of a country’s financial sector, we multiply these data on domestic loans to the private sector with GDP data from Eurostat (2017b). The variable was scaled down by a factor of 1,000,000 to ease the visibility of the variable's coefficient. The size of the financial sector is important for various reasons, most importantly as a determinant of the liquidity premium that banks must pay when they issue mortgage bonds. In countries with larger financial sectors these costs should be lower, as there is a trend towards more potential investors being available to buy or sell large amounts of bonds without affecting prices to their disadvantage.

We employ other control variables. The House Price Index from Eurostat (2017c) is included in our models, as house prices are the most important determinant of the size of consumer mortgages. The index measures changes in the prices of all residential properties purchased by households (e.g. apartments, single-family detached houses, etc.) in a country. The variable was scaled down by a factor of 10 to ease the visibility of the variable's coefficient. The variable Membership in the Eurozone is a dummy variable that indicates whether a country was a member in the Economic and Monetary Union of the European Union (EMU) at a given point in time. The variable is included in all of our models because the Member States that belong to the EMU coordinate their financial and economic policies more closely than those outside the EMU and are subject to the same monetary policy of the European Central Bank. The variable was scaled down by a factor of 10 to ease the visibility of the variable's coefficient.

For our robustness tests we employ further control variables. Cost of Resolving Insolvency is data from the World Bank’s Doing Business reports (The World Bank, 2017a). The variable measures the cost of mortgage insolvency proceedings as a percentage of an estate’s value. We control for this data as upon the default of a consumer these costs are an important determinant of the bank's overall losses resulting from the bad loan. The variable was scaled down by a factor of 1000 to ease the visibility of the variable's coefficient. We also employ data from The World Bank (2017b) to control for factors that are likely to affect banks’ interest rate spreads. Bank Return on Assets measures the efficiency of banks. The variable gives the commercial banks’ average annual net income after taxes as a percentage of their total yearly assets by country. The variable was scaled down by a factor of 10 to ease the visibility of the variable's coefficient. The Boone Indicator is a measure of market competition in the banking sector. It is computed as the elasticity of profits to marginal costs. An increase in the measure thus implies lower levels of competition. Market concentration is measured by the Lerner Index and the Largest Five Banks’ Asset Concentrations. The Lerner Index compares output prices and marginal costs—an increase in the index indicates lower levels of competition. The Largest Five Banks' Asset Concentrations indicates what share of a Member States’ total commercial banking assets are held by the five largest banks. The variable was scaled down by a factor of 10 to ease the visibility of the variable's coefficient. Table 5, below, presents summary statistics for all employed variables.

6 Estimation strategy and empirical models

We used our regression models to test the hypothesis that increasing the stringency of consumer protection legislation leads to a rise in consumer mortgage interest rates. We tested this hypothesis by fitting fixed effects models to monthly panel data on the average interest rates for long-term consumer mortgages in the EU Member States between January 2005 and August 2016. Of the 28 countries in our dataset, 4 had missing values for our dependent variables and one had missing values for some of our explanatory variables (see Table 5, above). A total of 23 countries were thus used to estimate our models. Where appropriate we interpolated some of the missing data using linear interpolation, e.g. where we had to transform quarterly data into monthly data or where we were able to complete a patchy time series in this way. We also excluded a few extreme outliers, i.e. data for months in which unusually high interest rates of over 10% were charged. This applied to about 80 observations, all from new, eastern European Member States of the EU.

We then searched for the optimal number of lags of our dependent variable Interest Rates for Long-Term Consumer Mortgages to be included in our models. To do so we fitted some initial models containing the main variables of our study and different numbers of lags of Interest Rates for Long-Term Consumer Mortgages and compared the AIC values of the models. We found that the model with three lagged variables had a much lower AIC value than the model with no lagged variable. We thus used the model specification with three lagged variables for further analysis. We realize that an OLS estimation of a dynamic model with lagged dependent variables can lead to biased coefficients. However, our dataset has a large number of time steps (i.e. months) compared to panels (i.e. countries). This greatly reduces the potential for dynamic panel bias. Thus, for the large number of timesteps that we have in our dataset, the bias is likely to be negligible and we therefore proceeded with the fixed effects estimator, rather than employing e.g. the Arellano‐Bond estimator (see e.g. Roodman, 2006).

A histogram of the residuals of our model showed that the residuals were skewed. We greatly reduced this problem by using a log transformation of our dependent variable which led to more normally distributed residuals. However, the results of the Shapiro–Wilk and Shapiro-Francia tests for normality were statistically significant (p-value < 0.01) indicating that the data did not originate from a normally distributed population. Based on OLS models we then tested for heteroskedasticity using the Breusch-Pagan/Cook-Weisberg test and for autocorrelation using the Wooldridge test and found signs of heteroskedasticity (p-value < 0.01) and first-order autocorrelation (p-value < 0.01). We therefore decided to fit the models with robust standard errors and to include lagged values of our dependent variable (see above). We also tested for multicollinearity between all explanatory variables using VIF (variance inflation factors). As was to be expected, we found high VIF values for the lagged values of our dependent variable. When these were excluded the mean VIF value was below 5. However, the individual VIF value for Benchmark Refinancing Cost was also high (51.60). It was possible to solve this problem by excluding the year dummies from our model, which resulted in a much lower VIF value (11.23). To show that this had no effect on our main results we therefore also included a model without time fixed effects in our robustness tests.

7 Results of the empirical study

7.1 Main results

Table 6 below presents the results of our estimation. The dependent variable of each of the models is Interest Rates for Long-Term Consumer Mortgages but they differed in the set of explanatory variables employed.

Our results show that making consumer protection for the case of early repayment more stringent results in an increase in interest rates for long-term consumer mortgages. This finding supports the theoretical argument that shifting the costs of early repayment of a mortgage loan to the creditor will increase the interest rate spread between the banks’ borrowing rate and lending rates and thus raises interest rates for the consumer. This finding is consistent across all our main models. For example, a total of 23 countries and 2014 observations were used to estimate model 1. The model has an R Square value of 0.89, meaning that 89% of the variance of Interest Rates for Long-Term Consumer Mortgages (LOG) in our dataset is explained by the model, which is a very good fit. Here the coefficient for the variable Consumer Protection for Early Repayment (Dummy) is statistically significant at the 5% level (p-value 0.013). We interpret this result in more detail in the section “The Effect of Consumer Protection for Early Repayment on Consumer Mortgage Interest Rates”, below.

In all models, the coefficients for the variable Benchmark Refinancing Cost are statistically significant (p-value < 0.001). As expected, the refinancing costs of banks have a highly statistically significant effect on the interest rates that consumers have to pay. In model 3 the coefficient for the variable Bank Return on Assets is statistically significant at the 1% level, indicating that a higher profitability of banks leads to lower consumer interest rates, though this effect seems to be very modest. In models 3 and 5 the coefficients for the variable Membership in the Eurozone are statistically significant at the 1% level. The signs of the coefficients are positive, indicating that our model predicts that consumer mortgage interest rates will be higher in countries that are members of the eurozone. Despite the fact that this result is rather surprising, we decided to keep the variable in all our models due to its theoretical importance as a control variable.

7.2 The effect of consumer protection for early repayment on consumer mortgage interest rates

The coefficient for the variable Consumer Protection for Early Repayment (Dummy) is statistically significant at the 5% level (p-value 0.013). This shows that if a country switches from no consumer protection for early repayments (i.e. compensation for the lender must be negotiated or damages must be paid) to a legal regime with consumer protection for early repayments (i.e. liability cap or no charge) model 1 predicts that the average mortgage interest rate will increase by on average 3.15%. Although this result is in line with our theoretical predictions and descriptive empirical observations, the size of the effect is modest. However, compared to the coefficients of all the other explanatory variables, the effect size is still relatively large. If we do not include lags of our dependent variable in our model (see robustness tests, below), the size of the coefficient is furthermore considerably larger (0.14). A possible explanation for the rather modest size of the coefficient is that banks may only slowly start to ease in the anticipated higher costs resulting from consumer protection. Thus, the coefficients of the lags of our dependent variable already partly account for the change in interest rates resulting from a tightening of consumer protection. Another possible explanation for the rather modest size of the coefficient is that banks’ increase in marginal costs resulting from consumers' right to early repayment are spread over numerous high risk and low risk consumers. Thus, the effect on average mortgage interest rates is less than in a scenario where these costs can be passed on to high risk consumers only. An example of such a scenario are mortgage lenders which offer consumers a voluntary early repayment option at an increased price determined by the market forces, see Sect. 8 “Conclusions”, below.

Model 1 predicts that the average mortgage interest rate will increase by on average 3.15%. For example, if the average mortgage interest rate before the change was 5%, then the model predicts that after a change in consumer protection the interest rate will be about 5.16%. Let us further assume that the average mortgage loan in a given country is 200.000 Euros. Raising the level of consumer protection in that country would thus on average lead to additional interest payments for the consumer amounting to roughly 315 Euros per year, totalling 10,000 euros before the change and 10,315 euros after the change. This relates to the interest rate spread of a given bank as follows. Assuming that the refinancing costs of the bank are 3%, the interest rate spread in our example would be 2% before the change and 2.16% after that change. Thus, as a result of a change in the level of consumer protection the bank would increase its net margin by 8%. These results provide some support for our theoretical argument that the effect that more stringent consumer protection legislation leads to higher consumer mortgage interest rates is different in times of high and low interest rates. We discuss these considerations in more detail in the section “Considerations on the Effect of the Right to Early Repayments in Periods of High Interest Rates”, below.

7.3 Considerations on the effect of the right to early repayments in periods of high interest rates

Our empirical observations are in line with the argument that the premium that banks charge their customers should be bigger in times of high interest rates. After all, the risk of early repayment by the consumer increases with the interest rate as an increasing interest rate also increases the risk, that the future interest rate will be lower than the present interest rate. This would lead to early repayment and a corresponding loss to the bank. We tried to explicitly test the hypothesis that the interest rate spread increases with the market interest rate in member states with no or capped compensation for expectation damages in case of early repayment. To do so we fitted several models (not shown) to investigate whether in times of high interest rates the mortgage banks’ interest rate spread is higher in countries with high levels of consumer protection than in countries with low levels of consumer protection. However, none of these models provided results that clearly supported or reject our argument. This might be due to the following reasons. First, we were unable to obtain primary data on the refinancing costs of mortgage banks in each EU member state. We thus had to approximate the mortgage banks spread using data on consumer mortgage loans’ interest rates that were on the country level and banks’ refinancing rates that were at the EU level. This approach proved particularly difficult for some smaller and new EU member states, where mortgage markets are in tendency less developed and thus interest rates are sometimes heavily driven by unobserved country effects. Second, most countries in our dataset introduced the right to early repayment as a reaction to the increased number of consumer foreclosures occurring in the global financial crises. However, as a response to this crisis the European Central Bank also introduced a low interest rate policy that lasted up to today. We therefore do not have sufficient data to comprehensively analyse how mortgage banks react to the right to early repayment in high interest rate periods. We can only conjecture that mortgage banks would under such conditions either shorten the maximum period of the fixed interest mortgage contracts they offer, or they would replace these contracts by variable interest rate contracts. Both options are clearly unfavourable to the average consumer. We obtained anecdotal evidence from Austria, a country in which a right to early repayment with a capped damage compensation exists, that in periods of high interest rates banks only offer fixed interest rate mortgages with short durations. By limiting the duration of these mortgages contracts, banks reduce the risk that consumers repay the old mortgage and take out a new one at a lower interest rate in the future. This anecdotical evidence is supported by information received from directors and employees of German savings banks, who insist that the typical German mortgage credit, which has a fixed interest rate for 5, 10, or 15 years and allows for stable planning of house financing is only possible because premature repayment leads to compensation of the bank’s expectation damages. The reaction to high interest rates under a right to early repayment might therefore not be extraordinary spreads but a change of the business model from fixed to variable interest rates and from long term to short term credits. Variable interests would exclude and short term credits would reduce damages of the bank, when the credit is prematurely repaid, because with these business models the bank loan interest rate can follow closely the refinancing rate. This removes or reduces the risk from a right to early repayment in a low interest period for credit contracts, which were concluded in a high interest period.

7.4 Robustness tests

In our robustness checks we ran various modifications of our main model 1 which we have discussed in the previous paragraphs. The results of these checks are presented in Table 7, below. In model 1 of our robustness tests, we do not include lags of our dependent variable Interest Rates for Long-Term Consumer Mortgages. In this model the magnitude of the coefficient of the variable Consumer Protection for Early Repayment (Dummy) is much greater than those of the models that include lags, see the above explanations. In model 2 we follow some of the considerations laid down in our estimation strategy (see above) and exclude the year dummies from our model, leading to a much lower VIF value for Benchmark Refinancing Cost (11.23). Model 3 replaces the main explanatory dummy variable that we used to test the research hypothesis by the categorical variable Consumer Protection for Early Repayment (Categorical), see our discussion on the Consumer Protection Index, above. In this model, the coefficient of the category medium “Liability cap or lender's additional administrative expenses” is statistically significant at the 5% level, while the coefficient of the category high “No charge” is not. Model 4 replaces our main benchmark for the lender’s refinancing costs, i.e. the German mortgage bonds, with our alternative benchmark, i.e. the interest rates for long-term governmental bonds for each Member State (see above). In this model our main finding does not persist, the coefficient of the variable Consumer Protection for Early Repayment (Dummy) is not statistically significant at any conventional level of significance. However, in model 5, which combines both the changes introduced in models 3 and 4, the coefficient of the category high “No charge” of the Consumer Protection for Early Repayment (Categorical) variable, is statistically significant at the 5% level. Model 6 and 7 are first difference regression models. The former excludes year dummy variables and the latter includes them. Here the coefficient of the Consumer Protection for Early Repayment (Dummy) variable is statistically significant in the former model, but not in the latter model. In both models the mean VIF values are very low (Model 6: 1.06 and Model 7: 5.42). Overall, our main result, i.e. that an increase in consumer protection for early repayments leads to higher interest rates for mortgages, is stable throughout almost all model specifications.

8 Conclusions

This paper shows analytically that a right to early repayment of a long-term mortgage consumer credit with fixed interest rates in European consumer protection law might decrease rather than increase consumer welfare. It might increase the welfare of a risk averse consumer if such a right decreases the variance of expected future income streams of the consumer and causes therefore a risk spreading insurance effect without changing the expected gain from the contract If this right would be restricted to the elimination of personal risks, which force a consumer or her relatives to sell the real estate and repay the credit it would reduce variance, serve an insurance function and probably increase consumer welfare. This finding is further supported, if research results of behavioral economics, especially loss aversion, status quo bias and weighted probabilities are included in the analysis.

A right to early repayment can however increase the variance of expected gains from the credit contract, when interest rates fall after contract formation, and it becomes profitable to replace the old high interest credit by a new low interest credit. Then a consumer right of early repayment increases the variance of future income streams and leads to a welfare loss for risk averse consumers if her expected gain from the contract remains unchanged. The right is then not in his or her interest at the time the contract is concluded. This part of the right has not the character of an insurance but of a lottery or an option contract. A risk averse consumer has not the willingness to pay the full costs of the option as part of the interest rate of the credit. This part of the right to early repayment reduces consumer welfare. On the contrary, the traditional rule of expectation damages for breach of contract removes any incentives to replace an old high interest contract with a new low interest contract and is insofar more efficient. Also, the right to early repayment places a lump risk on banks because in a period of low interests all debtors have an incentive to end the contract. This might either lead to excessive interest rate mark ups in high interest periods or to a withdrawal of banks from offering long term fixed interest rates for consumer mortgage credits. A restricted right to early repayment is therefore advisable. A bright line rule, which combines consumer protection with consumer welfare and economic efficiency could be to grant the right only to those consumers, who must sell their home and are therefore forced to repay the loan prematurely.

We show in an empirical panel study with monthly interest rates of EU member states from 2005 to 2017 that the consumer’s right to early repayment without an obligation to compensate the bank for its expectation damages comes at a cost for the consumer and increases the interest rate spread between bank lending rates and refinancing rates. This finding is in line with economic theory, which predicts that an increase of marginal costs, which affects all suppliers alike must increase the equilibrium price of a good or service. This holds in competitive as well as in monopolistic markets. Our empirical finding is hardly surprising for an economist but still important for lawyers and politicians in the field of consumer protection, who should sometimes be reminded that consumer protection is not a free lunch for the consumer. That in fact an early repayment right increases the interest rate spread and consequently the bank loan rate is as such neither an argument for nor against a right to premature repayment of a long-term fixed interest rate credit. The right might insure the consumer against the personal risk that she must unexpectedly and prematurely sell a self-used real estate, which the credit financed. He or she might then be confronted with a damage compensation, which often runs in the thousands or ten thousands of Euro. We are however skeptical whether this benevolent effect for the consumer prevails.