Abstract

Previous research has not explained the use of real option clause in franchise contracting. The real option clause has two economic functions: To reduce transaction costs by mitigating opportunism risk and to increase strategic rents by exploiting the profit potential from future upside opportunities under uncertainty. We argue that franchisors will more likely use a real option clause (ROC) in franchise contracts under high behavioral uncertainty, high franchisors’ transaction-specific investments relative to franchisees’ and long contract duration. In addition, by combining transaction cost theory and real option theory, our study provides a new explanation for the impact of environmental uncertainty on the use of ROC in franchise networks by showing that there exists a U-shaped relationship between environmental uncertainty and the franchisor’s use of ROC. Overall, the data from German and Swiss franchise systems provide support of the research model.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

There is a room for ROT (real options theory) to improve its integration potential by joining TCE (transaction cost economics)….

(Trigeorgis and Reuer 2017)

1 Introduction

Firms choose different governance structures to safeguard their specific investments and exploit profit opportunities under uncertainty. Previous research has mainly applied transaction cost theory (TCT) to show that hierarchical structures are more efficient to preserve transaction-specific investments in presence of contractual hazards (Williamson 1985, 1991; Gatignon and Anderson 1988; Zhao et al. 2004). A higher level of control facilitates coordination under increasing environmental uncertainty and protects firms’ interests in preserving transaction-specific investments from possible exploitation (Zhao et al. 2004). However, real options theory (ROT) has challenged the transaction cost theory prediction of using hierarchical control in highly uncertain business environments (e. g. Brouthers et al. 2008; Folta 1998; Kogut 1991; Wooster et al. 2016) by viewing environmental uncertainty as an important source of profit opportunities. Hence, under a high level of uncertainty, it is more valuable for the firm to obtain real options, which offer the right to increase equity investments when upside opportunities arise (Trigeorgis and Reuer 2017).

In interfirm networks, such as joint ventures and franchise networks, protecting prior investments and exploiting future profit opportunities become more challenging as uncertainties grow due to potential partner opportunism and environmental contingencies. To address this governance issue, interfirm networks are structured by equity and non-equity arrangements. For instance, most franchise networks are characterized by a plural form that combines two governance structures: integration through company-owned outlets and non-integration through franchised outlets (Cliquet 2001; Baker and Dant 2008). Similar to joint ventures (Chi and McGuire 1996; Chi and Seth 2002; Folta 1998; Reuer and Tong 2005; Tong and Li 2013), franchising provides the franchisor with the option of incremental expansion by reducing the downside risk and exploiting the upside opportunities under conditions of uncertainty. Hence the governance form of franchising has an embedded implicit call option (Bowman and Hurry 1993), since it offers the franchisor the opportunity to retain future profit opportunities (as strategic rents) by increasing its equity stake (i.e. the proportion of company-owned outlets). However, to exploit the profit potential from future upside opportunities in the network, it is necessary to have a real option clause (ROC) included in the franchise contract. With ROC specified in the franchise contract, the franchisor obtains the right to acquire additional equity from franchise partners at the termination of the contract, thereby protecting its specific investments and obtaining control over the expansion of the network by increasing strategic flexibility.

Although previous research applied the real options approach in the field of joint ventures (Chi and McGuire 1996; Chi and Seth 2002; Kogut 1991; Estrada et al. 2010; Reuer and Tong 2005; Tong and Li 2013), licensing (Jiang et al. 2009; Ziedonis 2007) and franchising (Baldi 2016; Gorovaia and Windsperger 2013; Liang et al. 2013), no previous study has used a combined perspective of TCT and ROT to explain the franchisor’s choice of explicit call option clause as safeguarding and strategic flexibility mechanism in franchise contracting. We address this gap by exploring the role of uncertainty and transaction-specific investments for the use of real option clauses in franchise contracting.

What is the contribution of this study? This study adds to the literature on real options in franchise contracting by integrating TCT and ROT perspectives to explain the franchisor’s choice of ROC. First, based on TCT reasoning, we argue that the likelihood of the franchisor’s use of ROC will increase with behavioral uncertainty as well as with the franchisor’s transaction-specific investments, while it will decrease with franchisees’ transaction-specific investments. In addition, based on the adaptation view of governance (Simon 1951; Williamson 1975; Gulati et al. 2005), we hypothesize that the franchisor will less likely include the ROC (as a disincentive for franchisees) in the franchise contract when environmental uncertainty requires more local responsiveness to acquire local market information. Second, according to ROT, the ROC functions as a strategic flexibility mechanism in a franchise contract that offers the franchisor the right to claim upside opportunities (Reuer and Tong 2005). We argue that the franchisor will more likely use a ROC if environmental uncertainty is high to retain the future profit opportunities (strategic rents) by acquiring franchisee-owned outlets. Specifically, by combining TCT and ROT reasoning, we show that environmental uncertainty has a U-shaped relationship with the use of explicit call options, due to the trade-off between the local responsiveness effect and the strategic flexibility effect of ROC. Under low levels of uncertainty, the positive local responsiveness effect of franchisees’ higher incentives under contracts without ROC dominates the strategic value increasing effect of higher flexibility under ROC. If environmental uncertainty is relatively high, the strategic value increasing effect of using ROC exceeds the transaction cost savings effect due to higher local responsiveness under contracts without ROC. Therefore, our study provides a new explanation for the impact of environmental uncertainty on the use of ROC in franchise networks by showing that there exists a U-shaped relationship between environmental uncertainty and the franchisor’s use of ROC.

This paper is organized as follows: The next section discusses the role of the ROC in franchise contracting. Section three develops the transaction cost and real option hypotheses to explain the franchisor’s use of real option clauses in franchise contracting. Section four presents and discusses the results of empirical analysis. Finally, some conclusions are derived.

2 Real option clause in franchise contracts

The ROC in franchise contracts provides several potential advantages, mainly to the franchisor. First, franchisors often acquire franchisee-owned outlets at a reduced price, since they are not obliged to recognize any goodwill that may have been built up by the franchisees over time (Franchise Business 2012). Besides, the option clause could also include that the repurchase price paid by the franchisor should not be higher than the original franchise fees (Franchisevest 2015). Such methods undermine any contribution made by franchisees to the system, increasing the likelihood that the franchisor’s buy-back arrangement will generate significant profits. Thus, franchisors could then sell the outlets bought at depreciated rates to other franchisees for substantially higher prices (Sebastian 2008). Second, franchisees may fail to pay all the due fees to the franchisor by the contract termination period or even after the contract ends, in which case the franchisor could offer a reduced price to buy the franchise minus unpaid debts and, potentially, litigation costs. Third, without the call option clause, the franchisor may fail to retain a specific prime location in a city or densely populated spot, which has the potential to be frequented continuously by new customers, or fail to retain the old customers who are familiar with the location. Such a location, with a significant customer base, almost guarantees continued success. Forth, in case of contract renewal, franchisees are often required to either pay for a renewal fee, pay transfer fees if the franchise is sold to other franchisees (Frazer 1998), invest significant amounts in their franchise if they want to continue (Blair and Lafontaine 2005), apply new contract terms (Murray 2006), or obtain shorter contracts (Brickley et al. 2006). Under these conditions, franchisees might choose to sell their franchises because of high renewal costs. However, if franchisors did not use an explicit call option in the franchise contract, they would lack the necessary bargaining power to set the desired amount for the renewal costs. Both franchise partners would expect that the lack of a ROC gives space for negotiations on the renewal costs because if they fail to agree, the franchisee has the possibility to find third parties who may be willing to pay premiums. In such cases, the franchisor might lose some of the renewal advantages without using an explicit call option. Moreover, the explicit call option serves to curb franchisees’ possible deviation from system standards that are set in accordance with the system-specific know-how and brand name, because the threat from the buy-back option may prevent franchisees from engaging in opportunistic behavior.

3 Theory and hypotheses

We combine TCT and ROT to explain the franchisor’s choice of explicit call options as safeguarding and strategic flexibility mechanism in franchise contracting. TCT reasoning has influenced the empirical analysis of contracts in general and contractual clauses in particular (e.g. Lafontaine and Slade 2014). The theory articulates the importance of contracts in interorganizational networks to safeguard transaction-specific investments under environmental and behavioral uncertainties (Williamson 1991; Wathne and Heide 2000). Traditional TCT predicts that franchisors threatened by uncertainties will find it more economizing to increase control by specifying more contract terms.

The ROT has recently enjoyed an increasing recognition due to its focus on predicting the influence of uncertainty on contract and governance design (e. g. Brouthers et al. 2008; Folta 1998; Kogut 1991; Wooster et al. 2016; Trigeorgis and Reuer 2017). The theory argues that environmental uncertainties can be an important source of profit opportunities and franchisors that obtain call option rights instead of higher equity commitment may gain follow-on profit opportunities due to inter-organizational learning. Hence, the use of ROC offers franchisors the flexibility to enjoy upside benefits from greater variability in the value of franchises (Trigeorgis 2003) under high uncertainty. Therefore, based on real options reasoning, high uncertainties in the franchise environment (due to environmental changes and long contract duration) are expected to incentivize franchisors to use the ROC, since it provide them with future profit opportunities as higher strategic rents (Trigeorgis 2003; Jarrow and Turnbull 2000). In the following we develop the TCT and the ROT hypotheses in detail.

4 Transaction-specific investments

According to TCT, the design of contract terms should serve to safeguard transaction-specific investments and align franchise partner objectives in order to diminish opportunistic behavior (Wathne and Heide 2000). Following Williamson (1979, 1985), asset specificity refers to physical, human, site and other dedicated specific investments. For instance, franchisors train franchisees’ staff, offer technical support, site selection support, continuous monitoring and guidelines on quality and service standards. Franchisors’ transaction-specific investments are expected to result in ‘locked in’ exchange relationships with more bargaining power for the franchisees. The latter could behave opportunistically by reducing their investments in the quality of products or services after having received the transaction-specific support from the franchisor. Consequently, when the franchisor’s specific investments are high relative to those of the franchisees, franchisors are subject to increased hold-up risks.

In franchising, contract terms serve as an intermediate solution to safeguard transaction-specific investments against the hold-up risks. Williamson (1983: 530) argues that “the incentive to exploit demand externalities may further be discouraged by requiring each franchisee to post a hostage and by making the franchises terminable”. A call option clause serves this purpose, as it allows the franchisor to acquire the franchisee outlet following the decision to terminate the franchise contract. As a result, explicit call options that offer franchisors the opportunity to increase the fraction of company-owned outlets by acquiring franchisee outlets on favourable conditions enhance their incentives to continue building the brand, investing in the local chains and training the local staff. Accordingly, we can formulate:

Hypothesis 1

Franchisor’s transaction-specific investments will increase the likelihood that the franchisor includes a ROC in franchise contracts.

Furthermore, franchising requires that both franchise partners make transaction-specific investments resulting in high quasi-rents for both partners. The bonding effect of bilateral investments offsets the need for more safeguarding and control mechanisms, because, as Klein puts it: it will “…assure quality by requiring franchisee investments in specific …assets that upon termination imply a capital loss larger than can be obtained by the franchisee if he cheats” (1980: 359). Thus, the partners’ quasi-rents of high transaction-specific investments might exceed the gains from potential hold-up (Klein 1995). This leads to cooperative behavior and reduces the need for specifying detailed contract terms in franchising (Hendrikse et al. 2015). Therefore, the higher the franchisees’ transaction-specific investments, the lower the hold-up risk and hence the need for the franchisor to use an option clause as a safeguarding mechanism.

Hypothesis 2

Franchisees’ transaction-specific investments will decrease the likelihood that the franchisor includes a ROC in franchise contracts.

5 Behavioral uncertainty

According to Geyskens et al. (2006: 521), “the effect of behavioral uncertainty is a performance evaluation problem”, which implies that it is difficult for the franchisor to verify whether compliance with an established agreement occurs or not. Opportunism is more probable under high uncertainty and ambiguity in measuring the performance and contractual compliance of the franchisees, due to the incompleteness of franchise contracts. To mitigate the risk of franchisees’ potential opportunism, the franchisor will exercise greater control over the activities of its partner (Williamson 1985). More specifically, the inclusion of the call option clause allows for higher franchisor control over the selection process of new franchisees, site locations of terminated franchise outlets and valuation methods of franchisees’ investments before exercising the option to acquire the outlet. Therefore, the inclusion of ROC in franchise contracts has the potential to mitigate partners’ opportunistic behavior (Reuer and Tong 2005) and provides incentives for the franchisor to exercise control to reduce behavioral uncertainty. Consequently, we expect a positive association between behavioural uncertainty and franchisor’s tendency to use the call option clause:

Hypothesis 3:

Behavioral uncertainty will increase the likelihood that the franchisor includes a ROC in franchise contracts.

6 Environmental uncertainty

Environmental uncertainty refers to market, competitive and institutional uncertainty. According to the TCT, these uncertainties increase transaction costs in exchange relationships (e.g. Rindfleisch and Heide 1997), which may lead to adaptation problems. Based on the adaptation view of governance (e.g. Simon 1951; Williamson 1973, 1975), a higher degree of environmental uncertainty necessitates more local responsiveness, i.e. a higher level of franchisees’ efforts to acquire and share local market knowledge. Thereby, the motivation of franchisees can be increased when the franchise contract does not contain a ROC. Consequently, under elevated levels of uncertainty, the franchisor is less likely to choose a ROC, in order to increase franchisees’ incentive for local information acquisition (Gulati et al. 2005; Hippmann and Windsperger 2013).

On the other hand, ROT presents a different perspective regarding the optimal level of commitment under conditions of environmental uncertainty (e.g. Leiblein 2003; Romer 2004). According to Chi and McGuire (1996) and Folta (1998), uncertainty requires more flexibility to capture the future profit opportunities. Reuer and Tong (2005) argue that the use of explicit call options increases the upside opportunities under conditions of high uncertainty in the macroeconomic, political, social and cultural environment. Li and Li (2010) propose that, under elevated levels of market uncertainty, firms choose ownership strategies that allow for future investment adjustments to capture the strategic rents. Based on this reasoning, the value of the call option is positively related to environmental uncertainty (Estrada et al. 2010; Ziedonis 2007). This result is important with regard to franchise contracts, as the franchisor’s option-to-acquire becomes more valuable under conditions of high local market uncertainty. Hence, the ROC increases franchisor’s strategic flexibility to exercise its right to potentially own more company-owned outlets after having acquired local market knowledge under conditions of higher uncertainty. Consequently, TCT and ROT have two different predictions: TCT predicts a negative relationship between environmental uncertainty and ROC, and ROT predicts a positive relationship between environmental uncertainty and ROC.

We conclude that the local responsiveness effect is based on the incentive and coordination function of the contract design, i.e. stronger incentives and higher local information processing capacity of franchisees to reduce transaction costs, and the strategic flexibility effect is based on the strategic function of the contract design. The franchisor can capture future profit opportunities under high levels of environmental uncertainty, if she/he includes ROC in the contract. Therefore, the franchisor’s decision making about the use of ROC has to consider both effects when designing franchise contracts.

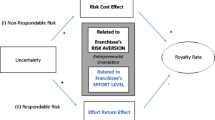

Combining ROT with TCT reasoning, we argue that an important curvilinear relationship between uncertainties and ROC exists (see Fig. 1). The first peak of the U-shaped curve can be explained by the coordination function of the contract design based on transaction cost reasoning. Under very low environmental uncertainty, the franchisor’s information asymmetry between the headquarters and the local market is low enabling her/him to centralize decision making between the headquarters and the local outlets. In this situation, the franchisor uses franchise contracts with ROC to increase the control capacity of the contract design.

Under low to moderate levels of environmental uncertainty the importance of franchisees’ local responsiveness and their entrepreneurial incentives increases, thereby requiring franchise contracts without ROC. A lower degree of contractual control (i.e. franchise contracts without ROC) might increase franchisees’ incentives for information sharing and local know-how acquisition (Gulati et al. 2005). However, as the level of uncertainty increases, the strategic flexibility advantage (i.e. higher strategic value) of the ROC will exceed the franchisor’s transaction cost savings due to franchisees’ higher local responsiveness under a contract without ROC (see Fig. 1). Thus, there is a trade-off between the strategic flexibility effect of ROC and the local responsiveness effect of ROC under increasing uncertainty. Under low to moderate levels of uncertainties, the residual income increasing effect, due to franchisees’ higher incentive for local information acquisition without ROC, is likely to exceed the strategic value-increasing effect of ROC. Conversely, under high environmental uncertainty, the strategic value-increasing effect of ROC is likely to exceed its residual income decreasing effect, due to the franchisee’s disincentive for local information acquisition under ROC. Consequently, we expect a U-shaped relationship between environmental uncertainty and ROC.

Hypothesis 4

There is a U-shaped relationship between environmental uncertainty and the likelihood that the franchisor includes a ROC in franchise contracts.

7 Contract duration

ROT researchers argue that uncertainty is elevated the longer the waiting time to option expiration (Folta and Leiblein 1994; Adner and Levinthal 2004a, 2004b; Estrada et al. 2010). To benefit from the holding period, during which the franchisor could learn about local market uncertainty and a franchisee’s value creation potential, a ROC should be used. Hence, with increased contract duration, the value of the real option becomes more attractive, because the franchisor as option holder obtains unlimited upside opportunity and limited downside loss. Cuypers and Martin (2010) and Estrade et al. (2010) argue that the duration of holding an option positively influences its value since longer time horizons create more chances for the option “to become in-the-money.” Therefore, a longer contract duration enables the option holder to collect additional information through inter-organizational learning and thus increases the upside opportunities under conditions of uncertainty (Folta 1998; Jiang et al. 2009). Applied to franchising, it may be expected that the franchisors will use the ROC, in order to gain from the longer contract duration that is associated with inter-organizational learning and higher option value.

Hypothesis 5:

Longer contract durations will increase the likelihood that the franchisor includes a ROC in franchise contracts.

8 Empirical analysis

8.1 Data collection

To empirically test the hypotheses, we collected the data from the franchising sector in Germany and Switzerland. Targets for data collection were drawn from the directory of the German Franchise Federation (DFV), “Franchise Wirtschaft,” and the Swiss Franchise Association, which together listed 1013 franchise systems operating in these countries. Prior to data collection, we decided to interview franchise professionals from respective franchise associations, which enabled several preliminary steps to be taken with regard to questionnaire development and refinement. Hence, we employed a reduced judgmental sampling following a pre-test with 20 franchisors on the basis of two criteria: (a) that a minimum number of years of experience and (b) a minimum number of outlets would provide the franchisor with a higher level of knowledge of the relevant variables related to the franchise partners and the local market environment. More specifically, the system should have operated franchising for at least two years prior to data collection, and second, it should run at least five operating outlets. The selection criteria reduced the pool of potential respondents to 176 Swiss and 491 German franchise systems, respectively. Consequently, the questionnaire was mailed to 667 franchise networks, and interviews conducted with senior managers responsible namely for franchise. This methodology was based on the key informant approach (McKendall and Wagner III 1997). The response rate was approximately 17% from Switzerland and 28% from Germany, comprising 166 franchise systems. However, due to missing values (and regression techniques that account only for completely filled rows), 102 observations, representing about 10% of the population, could be used.

We further examined whether the data obtained from the observations are driven by early versus late responses (Armstrong and Overton 1977) by categorizing late respondents as proxies for the group of non-respondents. Those who responded by completing the questionnaire four weeks after the first group of responders were compared (with respect to age, size, royalties and advertising fees) to those who did not respond. The comparison allowed to assess whether non-response bias was an issue. No significant differences emerged between the two respondent groups.

Additionally, we assessed whether the common method variance was present in the data using the Harman’s single-factor test (Podsakoff et al. 2003). After running explorative factor analysis on all items, five distinct factors with an eigenvalue greater than 10 were apparent. The first component accounted for 21 percent of the variance. Using principal component factor analysis with varimax rotation and confirmatory factor analysis the five-factor solution was confirmed for the items presented in the study (Anderson and Gerbing 1988) explaining 64.76 percent of the variance. Thus, as no factor accounted for most of the variance, it suggests that common method variance is unlikely to confound the interpretations of the results. Further, the common-method bias from self-reported measures is unlikely to inflate the hypothesized relationships given that in this study the nature and scaling of items of dependent and independent variables are different (Podsakoff et al. 2003).

9 Measures

9.1 Dependent variable

9.1.1 ROC

The real option clause was operationalized in a similar way to the coding used by Reuer and Tong (2005) and Tong and Li (2013) in their work on joint ventures. The variable indicates whether or not the franchise contract contains the explicit call option right. The variable is coded with 1 if the call option right was used, and 0 otherwise (i.e., the options right is not mentioned in the contract).

9.2 Independent variables

Franchisor’s transaction-specific investments This construct represents franchisors’ idiosyncratic investments in human capital, technical, and facility/equipment related assets. Adapted from Heide and John (1990) and Geyskens et al. (2006), we ask franchisors to rate their initial investments on a seven-point Likert scale regarding the expenses incurred to train their franchisees at the beginning of the contract, the expenses for technical support provided to franchisees at the beginning of the relationship, and the expenses of setting-up local outlets. The construct reliability of this scale assessed by Cronbach’s alpha (α), composite reliability (CR) and average variance extracted (AVE) are relatively high (α = 0.64, CR = 0.73, AVE = 0.50).

Franchisees’ transaction-specific investments Franchisees’ transaction-specific investments were derived by asking the franchisor to specify the average investment that a franchisee needs to undertake to build a new franchised outlet (in Euro). This measure is based on Dnes (1993), which measured the monetary value of franchisees’ initial investments when setting up a local outlet.

Behavioral uncertainty Behavioral uncertainty represents the difficulty of firms to monitor partners’ compliance with established contractual rules (John and Weitz 1989; Rindfleisch and Heide 1997). Adapted from John and Weitz (1989), we operationalize behavioral uncertainty by asking franchisors to assess the following items on a 7-point Likert scale: difficulty to measure performance, to monitor franchisees behavior and the difficulty to assess capabilities and competencies of franchisees (α = 0.76, CR = 74, AVE = 0.50).

Environmental uncertainty Although different measures have been used to operationalize environmental uncertainty, they commonly embody the unpredictability of the environment (e.g. Rindfleisch and Heide 1997; Geyskens et al. 2006). Adapted from Celly and Frazier (1996) and John and Weitz (1989), we ask franchisors to assess environmental uncertainty on a seven-point Likert scale regarding outlet sales’ fluctuations, local market unpredictability and changes of local economic environment (α = 0.74, CR = 73, AVE = 0.51).

Contract duration Based on Vázquez (2007) and Hendrikse et al. (2015), we ask franchisors regarding the number of years stipulated in franchise contracts to measure contract duration.

9.3 Control variables

Age of the franchising system represents the number of years since the first franchise outlet was opened. Since age is an indicator of experience, it can be predicted that older franchise systems have more experience cooperating with franchisees and sensing the strategic importance of using the ROC in the franchise contracts (Reuer and Arino 2007).

Size represents the number of employees in franchisor’s headquarters. Transaction cost proponents highlight that larger firms have more control capacity (Erramilli and Rao 1993). Therefore, it may be the case that franchise systems that have more employees in their headquarters can realize coordination, monitoring and reputation advantages, which may reduce the need for a ROC as a control mechanism in the franchise contracts.

Sector represents whether the franchise system operates in manufacturing or service industries. This may be worth controlling for given that intangible assets (please see the appendix for details) vary across different sectors. Service franchising firms may need more local market know-how compared to product franchising firms (Blomstermo et al. 2006; Zeithaml et al. 1985). The greater the extent of intangible assets of the partners, the more important is the need to monitor franchisees by using a ROC (Tong and Li 2013).

Franchisor’s brand name A strong brand name may require a higher level of contractual control by including a call option clause. Adapted from Barthélemy (2008), we ask franchisors to assess its networks’ brand-name advantage compared to its competitors with respect to brand recognition, strength, reputation and quality (α = 0.75, CR = 0.80, AVE = 0.50).

Proportion of company-owned outlets (PCO) signals the level of reputation strength of the franchise chain (Gallini and Lutz 1992). Company-owned outlets reflect the credibility of a franchisor’s commitment to maintain the value of the brand name. Hence, franchise systems with strong reputation may increase their control by using ROC.

Franchisor’s formal visits Franchisor’s average number of annual visits to franchisee outlets represents its monitoring intensity due to performance measurement problems. Hence, this control mechanism is used by franchisors to assess whether franchisees comply with the contractual agreement (Quinn 1999; Doherty and Alexander. 2006; Vázquez 2008). Hence franchisors with greater performance measurement problems may increase control by using a ROC.

Multi-unit franchising (MUF) The franchisee that gains the right to own several outlets by demonstrating high entrepreneurial capabilities might have a stronger bargaining power (Michael 2000) to negotiate against the inclusion of ROC in franchise contracts. To measure MUF, we calculate the proportion of the owned-outlets to the number of franchisees as previously used by Griessmair et al. (2014).

Royalties A higher royalty rate is associated with a higher level of contractual control by using ROC, since it indicates higher importance of the franchisor’s inputs for the generation of the residual income in the franchise system.

All items of the subjective measures of the constructs subject to principal component factor analysis and confirmatory factor analysis (Anderson and Gerbing 1988) provide support to the discriminant validity. Table 1 shows that the variance extracted across all the constructs is greater than the squared correlation between constructs.

10 Regression Analysis

Descriptive statistics and Pearson correlation coefficients are reported in Table 2. The results show that 63 percent of the franchise systems use the call option clause in their contracts. In addition to correlations, low variance inflation factors (between 1.06 and 6.51) indicate that the results of the study should not be affected by multicollinearity.

To test the hypotheses regarding the likelihood of franchisor’s use of ROC in franchise contracts, logit and probit regression analysis were carried out. Table 3 provides the results of the regression analysis. Estimations were performed on the final sample of 102 German and Swiss networks. First, we control for the potential influence of franchisor’s brand name, proportion of company-owned outlets, annual number of franchisor’s visits to franchisee outlets, multi-unit franchising and royalties on ROC. We find that the proportion of company-owned outlets shows a positive effect on ROC supporting the view that a high PCO—as proxy for a strong brand reputation—requires more contractual control. Furthermore, we find partial evidence that multi-unit franchising increases franchisor’s use of ROC in franchise contracts indicating that the franchisor may try to capture the higher residual income stream of a multi-unit franchisee in case of contract termination. Finally, we find no influence of royalty rates, franchisor visits and brand name on ROC.

Second, we add the TCT and ROT variables to the regression equation (see Model 2 and 3 as well as Model 5 and 6). Both logit and probit results highlight that the franchisor’s decision to include the call option clause is influenced by transaction-specific investments, behavioral uncertainty, environmental uncertainty and contract duration. The data support the hypothesis that the franchisor’s transaction-specific investments increase the propensity to include the ROC as a safeguarding and control device in franchise contracts. Conversely, high franchisees’ transaction-specific investments are negatively related to the franchisor’s use of ROC. The bonding effect of high franchisees’ transaction-specific investments will lessen the franchisor’s need to exercise control by including a ROC in the franchise contract. Hence, the data support the first two hypotheses (H1, H2).

In addition, based on TCT reasoning, the franchisor’s use of ROC is positively related to behavioral uncertainty, which increases the likelihood that the franchisor uses a ROC. The result of the regression analysis is consistent with the hypothesis (H3) that the ROC can provide contractual safeguards when the franchisor experiences difficulties in measuring franchisees’ performance, monitoring their behavior, and assessing their capabilities and competencies. Furthermore, the data supports hypothesis H4 that there is a significant U-shaped relationship between environmental uncertainties and the use of ROC, implying that the likelihood of using a ROC is initially decreasing and then increasing with rising environmental uncertainty, due to the trade-off between the local responsiveness effect and the strategic flexibility effect of ROC under increasing uncertainty (see Fig. 2). Figure 2 portrays how a marginal increase in the level of environmental uncertainty increases the probability of using ROC while taking into account the potential effect of all other variables.

Further, the data support hypothesis H5 that longer contract duration will positively impact the likelihood that the franchisor uses a ROC. This is because longer contract duration is associated with inter-organizational learning resulting in higher upside opportunities.

In sum, the inclusion of both TCT and ROT variables in the research model increases the explanatory power significantly ([LR] χ2 (4) = 5 to [LR] χ2 (15) = 37). All models are significant, and likelihood ratio tests (i.e., –2[L (b) – L (b1)] ~ χ2) show that the variables in Models 1–3 and 4–6 are jointly significant (all p < 0.001). Overall, the correct classification (78.4% or 76.6% respectively) and the increase in Pseudo R2 (0.169 to 0.39) represent a decent model fit.

11 Discussion and implications

The aim of this study is to explain the franchisor’s use of ROC in franchise contracting. According to the TCT and ROT, explicit call options have both a safeguarding/control and strategic value creation function. ROC functions as a safeguarding and control mechanism to prevent franchisees from potential opportunistic behavior while at the same time motivating the franchisor to invest in system-specific know-how and brand name that are crucial to the success of the network. In addition, ROC enables the franchisor to increase strategic flexibility resulting in higher strategic rents under conditions of high environmental uncertainty.

First, based on TCT, we show that the likelihood of the franchisor’s use of ROC increases with behavioral uncertainty as well as the franchisor’s transaction-specific investments. However, franchisees’ transaction-specific investments diminish franchisors’ tendency to use explicit call options as a control mechanism. The franchisor will less likely choose a ROC as a control mechanism when high franchisees’ transaction-specific investments mitigate exchange hazards due to their bonding effect. Second, the findings indicate that franchisors will more likely use ROC as strategic value creation mechanism if environmental uncertainty is very high, in order to retain the future profit opportunities (strategic rents) in the network. Specifically, based on TCT and ROT, the results provide support of a U-shaped relationship between ROC and environmental uncertainty. This result highlights that there is a trade-off between the local responsiveness effect of ROC and the strategic flexibility effect of ROC under increasing uncertainty. Under low to moderate levels of environmental uncertainty, the franchisor will less likely include the ROC—as a disincentive mechanism for franchisees—in the franchise contract when environmental uncertainty requires more entrepreneurial responsiveness to acquire local market knowledge. However, under high environmental uncertainty, the strategic value-increasing effect of ROC may likely exceed its residual income decreasing effect, due to the franchisee’s lower incentive for local information acquisition under ROC. In other words, the absence of ROC can serve as an incentive mechanism for franchisees to collect local market information and reduce transaction costs, but as the degree of uncertainty increases so does the strategic value-increasing effect of ROC as strategic flexibility mechanism. Consequently, our study provides a new explanation of the impact of environmental uncertainty on ROC by combining transaction cost and real options reasoning. Finally, the findings support the ROT view that the use of ROC is positively related with contract duration, because its inclusion increases franchisor’s profit opportunities due to interorganizational learning. This is in line with previous research results (Jiang et al. 2009).

This study has important implications for researchers and franchisors. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first attempt to empirically explain the use of ROC in franchise contracting by combining TCT and ROT. Thereby it adds to the franchise and interorganizational network literature on contract design by showing that ROC (as component of contract design) has—in addition to the safeguarding function—an important strategic value creation function. More specifically, by explaining the transaction cost and the real option theory determinants of ROC in franchise contracting, our study extends previous work on explicit call options in interorganizational networks (Reuer and Tong 2005; Tong and Li 2013; Ziedonis 2007) in the following ways: First, by developing and testing a complete TCT model of ROC (i.e. including all TCT variables, such as behavioral uncertainty, environmental uncertainty and franchisor’s and franchisees’ transaction-specific investments), we add to the transaction cost economics literature on contract design. Second, based on the combined application of TCT and ROT, this study provides a new explanation for the influence of environmental uncertainty on the franchisor’s choice of ROC. It shows that environmental uncertainty has a U-shaped relationship with ROC. Moreover, the study also contributes to the broader alliance literature by responding to the call for the application of a combined TCT and ROT perspective on contract design issues in interfirm alliances (e.g. Chi and McGuire 1996; Folta 1998; Leiblein 2003; Sanchez 2003; Trigeorgis and Reuer 2017).

The study has important managerial implications: Franchisors should consider both the safeguarding function and the strategic flexibility function of ROC when deciding about its use in franchise contracts. Based on our results, we can conclude that franchisors should include a ROC in the franchise contract under the following conditions: relatively high franchisor’s transaction-specific investments, high behavioural uncertainty, high environmental uncertainty and long contract duration. Franchise contracts with ROC lessen performance measurement problems and the opportunism risk under high transaction-specific investments and enable the exploitation of profit opportunities under high environmental uncertainty.

11.1 Limitations and future research

This study is subject to the following important limitations: First, since most of the franchise companies in this survey do not disclose contractual data, subjective data was collected. However, the literature shows that there is a strong positive correlation between objective and subjective indicators (Wall et al. 2004). Future research should test the generalizability of these results by using contractual data. In this line, the operationalization of the ROC (dependent variable) as a dummy variable may hide some information (e.g. how, when and price). Second, although environmental uncertainty consists of several dimensions (e.g. market and technological uncertainty), this study has not collected data regarding the different facets of environmental uncertainty. Therefore, we could not test the effects of the different dimensions of environmental uncertainty on ROC.

Third, while transaction cost and real option perspectives explain 38 percent of the variance of the ROC, other variables, not included in this study, may influence a franchisor’s use of ROC. In particular, variables derived from resource-based theory and bargaining power theory may influence the use of ROC in franchise contracts. According to Jiang et al. (2009) and Maritan and Alessandri (2007), a combined approach of real option theory and resource-based theory may explain the impact of the franchisor’s and franchisee's resources and capabilities on the use of explicit call options. In addition, based on the bargaining power perspective (e.g., Michael 2000; Choi and Triantis 2012), it is expected that a franchisor’s stronger bargaining power in designing franchise contracts may have an impact on the use of explicit call options. Third, future research can extend this work by focusing on possible interactions between call option rights and other contract clauses, such as resale price maintenance, tying arrangement or lease control. The bundling of contractual rights may lead to new results for the theory and practice of contract design (Hajdini and Raha 2018; Hajdini and Windsperger 2019; Schepker et al. 2014). Finally, future studies could investigate the antecedents of the use of ROC in different international franchise governance modes (such as joint venture franchising and master franchising franchising) (Konigsberg 2008; Jell-Ojobor and Windsperger 2014), since strategic flexibility is very important for the success of international franchise networks in highly uncertain international environments, for instance due to institutional and economic uncertainty.

12 Conclusion

Previous research has not explained the franchisor’s choice of using real option clauses in franchise contracting. The real option clause (as explicit call option) has both a safeguarding/control function to reduce transaction costs under high transaction-specific investments and exchange hazards, and a strategic flexibility function under high environmental uncertainty to increase strategic rents. Specifically, by combining TCT and ROT reasoning, we provide a new explanation for the impact of environmental uncertainty on franchisor’s use of ROC. Based on data from German and Swiss franchise sector, we show that environmental uncertainty has a curvilinear (U-shaped) relationship with franchisor’s use of ROC.

We hope our contribution inspires further research on the use of ROT to explain the contract design and governance of franchise networks. As argued by Ragozzino et al. (2016: 20), “future research might fruitfully focus on empirical contexts in which the valuation of opportunities is a crucial aspect of strategic objective pursued by firms. Such settings might include, among others,…the franchising of a brand.” Since the majority of franchise networks are characterized by a plural form consisting of company-owned and franchised outlets (Bradach 1997; Cliquet 2001), they combine flexibility through network relations and control through hierarchical relations in one franchise chain. However, most previous studies, mainly based on transaction cost theory and agency theory (Baker and Dant 2008; Lafontaine and Slade 2014), focus on control as transaction and agency costs savings mechanism to explain the governance structure of franchise firms. They do not apply ROT, which proposes that flexibility through more franchising may create strategic value under uncertainty (Trigeorgis 1996; McGrath 1999). Hence, we predict that the franchisor is likely to choose a higher proportion of franchisee-owned outlets under a high level of environmental uncertainty, in order to exploit possible future profit opportunities by increasing its equity stake. In this case, the franchisor has the option to expand and learn from network partners when choosing more franchisee-owned outlets at the time when it sets up a franchise network. Hence, under real option reasoning, the franchisor will choose a lower level of control and commitment to exploit potential upside opportunities and limit downside risk by providing flexibility when uncertainty is high. Therefore, future research should apply ROT, in combination with TCT, to test a new explanation of the ownership structure of franchise firms (Windsperger 2002).

References

Adner, R., & Levinthal, D. A. (2004a). What is not a real option: considering boundaries for the application of real options to business strategy. Academy of Management Review, 29, 74–85.

Adner, R., & Levinthal, D. A. (2004b). Real options and real tradeoffs. Academy of Management Review, 29, 120–126.

Anderson, J., & Gerbing, D. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411–423.

Armstrong, J. S., & Overton, T. S. (1977). Estimating non-response bias in mail surveys. Journal of Marketing Research, 14, 396–402.

Barthélemy, J. (2008). Opportunism, knowledge, and the performance of franchise chains. Strategic Management Journal, 29, 1451–1463.

Baker, B. L., & Dant, R. P. (2008). Stable plural forms in franchise systems: An examination of the evolution of ownership redirection research. In Strategy and governance of networks (pp. 87–112). Physica-Verlag HD.

Baldi, F. (2016). Multi-unit franchising strategies: a real option logic. Economia e Politica Industriale, 43, 175–217.

Blair, R. D., & Lafontaine, F. (2005). The economics of franchising. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Blomstermo, A., Sharma, D., & Sallis, J. (2006). Choice of foreign market entry mode in service firms. International Marketing Review, 23, 211–229.

Bowman, E. H., & Hurry, D. (1993). Strategy through the option lens: An integrated view of resource investments and the incremental-choice process. Academy of Management Review, 18, 760–782.

Bradach, J. L. (1997). Using the plural form in the management of restaurant chains. Administrative Science Quarterly, 42, 276–303.

Brickley, J. A., Misra, S., & Lawrence, V. H. (2006). Contract duration: Evidence from franchise contracts. Journal of Law and Economics, 49, 173–196.

Brouthers, K. D., Brouthers, L. E., & Werner, S. (2008). Real options, international entry mode choice and performance. Journal of Management Studies, 45, 936–960.

Celly, K. S., & Frazier, G. L. (1996). Outcome-based and behavior based coordination efforts in channel relationship. Journal of Marketing Research, 33(2), 200–210.

Chi, T., & McGuire, D. J. (1996). Collaborative ventures and value of learning: Integrating the transaction cost and strategic option perspectives on the choice of market entry modes. Journal of International Business Studies, 27(2), 285–307.

Chi, T., & Seth, A. (2002). Joint ventures through a real options lens. In F. L. Contractor & P. Lorange (Eds.), Cooperative strategies and alliances (pp. 71–87). Amsterdam: Pergamon.

Choi, A., & Triantis, G. (2012). The effect of bargaining power on contract design. Virginia Law Review, 98, 1665–1743.

Cliquet, G. (2001). Plural forms in store networks: A model for store network evolution. International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research, 10, 369–387.

Cuypers, I., & Martin, X. (2010). What makes and what does not make a real option? A study of international joint ventures. Journal of International Business Studies, 41, 47–69.

Dnes, A. W. (1993). A case-study analysis of franchise contract. The Journal of Legal Studies, 22, 367–393.

Doherty, A. M., & Alexander, N. (2006). Power and control in international retail franchising. Asia-Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 40, 292–316.

Estrada, I., de la Fuente, G., & Martín-Cruz, N. (2010). Technological joint venture formation under the real options approach. Research Policy, 39, 1185–1197.

Erramilli, M. K., & Rao, C. P. (1993). Service firms’ international entry-mode choice: a modified transaction cost analysis approach. Journal of Marketing, 57, 19–38.

Folta, T. B. (1998). Governance and uncertainty: The trade-off between administrative control and commitment. Strategic Management Journal, 19, 1007–1028.

Folta, T. B., & Leiblein, M. J. (1994). Technology acquisition and the choice of governance by established firms: Insights from option theory in a multinomial logit model. In Academy of management proceedings, Dallas, Texas.

Franchise Business (2012). When is it time to sell your Franchise?. Retrieved from https://www.franchisebusiness.com.au/news/when-is-it-time-to-sell-your-franchise#Z4mbpZfmPkOtWcRv.99. Accessed 15 January 2018.

Franchisevest (2015). Obligations of the franchise.https://www.franchisevest.com/wpl/sobre. Accessed 05 January 2017.

Franchise Wirtschaft. 2009/2010. 5.Jahrgang.

Frazer, L. (1998). Motivations for franchisors to use flat continuing franchise fees. The Journal of Consumer Marketing, 15, 587–596.

Gallini, N. T., & Lutz, N. A. (1992). Dual distribution and royalties in franchising. Journal of Law, Economics and Organization, 8, 471–501.

Gatignon, H., & Anderson, E. (1988). The multinational corporation’s degree of control over foreign subsidiaries: An empirical test of a transaction cost explanation. Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization, 4, 305–336.

Geyskens, I., Steenkamp, J. E. M., & Kumar, N. (2006). Make, buy, or ally: A transaction cost theory meta-analysis. Academy of Management Journal, 49, 519–543.

Gorovaia, N., & Windsperger, J. (2013). Real options, intangible resources and performance of franchise networks. Managerial and Decision Economics, 34, 183–194.

Griessmair, M., Hussain, D., & Windsperger, J. (2014). Trust and the tendency towards multi-unit franchising: A relational governance view. Journal of Business Research, 67(11), 2337–2345.

Gulati, R., Lawrence, P., & Puranam, P. (2005). Adaptation vertical relationships, beyond incentive conflict. Strategic Management Journal, 26(5), 415–440.

Hajdini, I., & Raha, A. (2018). Determinants of contractual restraints in franchise contracting. Managerial and Decision Economics, 39(7), 781–791.

Hajdini, I., & Windsperger, J. (2019). Contractual restraints and performance in franchise networks. Industrial Marketing Management, 82, 96–105.

Heide, J. B., & John, G. (1990). Alliances in industrial purchasing: The determinants of joint action in buyer-supplier relationships. Journal of Marketing Research, 27(1), 24–36.

Hendrikse, G., Hippmann, P., & Windsperger, J. (2015). Trust, transaction costs and contractual incompleteness in franchising. Small Business Economics, 44, 867–888.

Hippmann, P., & Windsperger, J. (2013). Formal and real authority in interorganizational networks: The case of joint ventures. Managerial and Decision Economics, 34, 319–327.

Jarrow, R. A., & Turnbull, S. M. (2000). The intersection of market and credit risk. Journal of Banking and Finance, 24, 271–299.

Jell-Ojobor, M., & Windsperger, J. (2014). The choice of governance modes of international franchise firms—Development of an integrative model. Journal of International Management, 20(2), 153–187.

Jiang, M. S., Aulakh, P. S., & Pan, Y. (2009). Licensing duration in foreign markets: A real options perspective. Journal of International Business Studies, 40, 559–577.

John, G., & Weitz, B. (1989). Salesforce compensation: An empirical investigation of factors related to use of salary versus incentive compensation. Journal of Marketing Research, 25(1), 1–14.

Klein, B. (1980). Transaction cost determinants of "unfair" contractual arrangements. American Economic Review, 70, 56–62.

Klein, B. (1995). The economics of franchise contracts. Journal of Corporate Finance, 2, 9–37.

Kogut, B. (1991). Joint ventures and the option to expand and acquire. Management Science, 37, 19–33.

Konigsberg, A. S. (2008). International franchising. New York: Juris Publishing.

Lafontaine, F., & Slade, M. (2014). Incentive and strategic contracting: Implications for the franchise decision. In K. Chatterjee & W. Samuelson (Eds.), Game theory and business applications (pp. 137–188). New York: Springer.

Leiblein, M. J. (2003). The choice of organizational governance form and performance: predictions from transaction cost, resource-based and real options theories. Journal of Management, 29, 937–961.

Li, J., & Li, Y. (2010). Flexibility versus commitment: MNEs’ ownership strategy in China. Journal of International Business Studies, 41, 1550–1571.

Liang, H., Lee, K.-J., Huang, J.-T., & Lei, H.-W. (2013). The optimal decisions in franchising under profit uncertainty. Economic Modelling, 31, 128–137.

Maritan, C.A., & Alessandri, T. M. (2007). Capabilities, real options, and the resource allocation process. In J. J. Reuer, & T. W. Tong (Eds.). Real options theory advances in strategic management, Volume 24, 307 – 332.

McGrath, R. G. (1999). Falling forward: real options reasoning and entrepreneurial failure. Academy of Management Review, 24, 13–30.

McKendall, M. A., & Wagner, J., III. (1997). Motive, opportunity, choice, and corporate illegality. Organization Science, 86, 624–647.

Michael, S. C. (2000). Investments to create bargaining power. Strategic Management Journal, 21, 497–514.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Podsakoff, N. P., & Lee, J.-Y. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 879–903.

Quinn, B. (1999). Control and support in an international franchise network. International Marketing Review, 16(4/5), 345–362.

Ragozzino, R., Reuer, J. J., & Trigeorgis, L. (2016). Real options in strategy and finance: Current gaps and future linkages. Academy of Management Perspectives, 30(4), 428–440.

Reuer, J. J., & Tong, T. W. (2005). Real options in international joint ventures. Journal of Management, 31, 403–423.

Reuer, J. J., & Arino, A. (2007). Strategic alliance contracts: Dimensions and determinants of contractual complexity. Strategic Management Journal, 28, 313–330.

Rindfleisch, A., & Heide, J. B. (1997). Transaction cost analysis: Past, present, and future applications. The Journal of Marketing, 61(4), 30–54.

Sanchez, R. (2003). Integrating transaction cost theory and real options theory. Managerial and Decision Economics, 24, 267–282.

Schepker, D. J., Oh, W. Y., Martynov, A., & Poppo, L. (2014). The many futures of contracts: Moving beyond structure and safeguarding to coordination and adaptation. Journal of Management, 40, 193–225.

Sebastian (2008). Selling your franchise: what are your rights?. https://ezinearticles.com/?Selling-Your-Franchise---What-Are-Your-Rights?andid=1171043. Accessed 07 November 2015.

Simon, H. A. (1951). A formal theory of the employment relationship. Econometrica, 19, 293–305.

Tong, T. W., & Li, S. (2013). The assignment of call option rights between partners in international joint ventures. Strategic Management Journal, 34, 1232–1243.

Trigeorgis, L. (1996). Real options: Managerial flexibility and strategy in resource allocation. Boston: MIT Press.

Trigeorgis, L. (2003). Real options and investment under uncertainty: what do we know? In P. Butzen and C. Fuss (Eds.), Firms’ investment and finance decisions: Theory and empirical methodology, 153–166.

Trigeorgis, L., & Reuer, J. J. (2017). Real options theory in strategic management. Strategic Management Journal, 38(1), 42–63.

Vázquez, L. (2007). Determinants of contract length in franchise contracts. Economics Letters, 97(2), 145–150.

Wathne, K., & Heide, J. (2000). Opportunism in interfirm relationships: forms, outcomes, and solutions. Journal of Marketing, 64, 36–51.

Wall, T., Michie, J., Patterson, M., Wood, S., Sheehan, M., Clegg, C., et al. (2004). On the validity of subjective measures of company performance. Personnel Psychology, 57, 95–118.

Williamson, O. E. (1973). Markets and hierarchies: Some elementary considerations. The American Economic Review, 63(2), 316–325.

Williamson, O. E. (1975). Markets and hierarchies: Analysis and antitrust implications. New York: Free Press.

Williamson, O. E. (1979). Transaction-cost economics: The governance of contractual relations. Journal of Law and Economics, 22, 233–261.

Wiliamson, O. E. (1983). Credible commitments: Using hostages to support exchange. American Economic Review, 73, 519–540.

Williamson, O. E. (1985). The economic institutions of capitalism: Firms, markets, relational contracting. New York: Free Press.

Williamson, O. E. (1991). Comparative economic organization – the analysis of discrete structural alternatives. Administrative Science Quarterly, 36, 269–296.

Windsperger, J. (2002). The structure of ownership rights in franchising networks: An incomplete contracting view. European Journal of Law and Economics, 13, 129–142.

Wooster, R. B., Blanco, L., & Sawyer, W. C. (2016). Equity commitment under uncertainty: A hierarchical model of real option entry mode choices. International Business Review, 25, 382–394.

Zeithaml, V. A., Parasuraman, A., & Berry, L. L. (1985). Problems and strategies in services marketing. Journal of Marketing, 49, 33–46.

Zhao, H., Luo, Y., & Suh, T. (2004). Transaction cost determinants and ownership-based entry mode choice: A meta-analytical review. Journal of International Business Studies, 35, 524–544.

Ziedonis, A. A. (2007). Real options in technology licensing. Management Science, 53, 1618–1633.

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by University of Vienna. The authors gratefully acknowledge financial support from the Austrian National Bank.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hajdini, I., Windsperger, J. Real options in franchise contracting: an application of transaction cost and real options theory. Eur J Law Econ 50, 313–337 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10657-020-09665-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10657-020-09665-3