Abstract

This paper analyses the effects of two recent reforms introduced in Italy in 2010 and 2011 in an attempt to reduce prison overcrowding. The first, introduced by the law no. 199 of 2010 on house arrest for prisoners with final conviction. The second, passed by the decree law no. 211 of 2011 on house arrest for criminals arrested awaiting trial. The results of econometric analysis prove that these reforms have achieved the objective to reduce the overcrowding of prisons in the short run, but in the long run they contribute to exacerbating the problem. A strong link was found between the several kinds of crime and the total number of prisoners. The two reforms seems to be positively correlated with property crimes (a pickpocketing and home thefts), but not with violent crimes. Finally, the impact of the changes introduced in the condition to be eligible to access at house arrest, has a negative impact on welfare.

Source: Italian Ministry of Justice

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

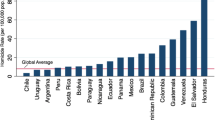

The highest rate of overcrowding in the Americas is 310% (El Salvador), in Africa 363% (Benin), in Asia 316% (Philippines), in Oceania 217% (French Polynesia), in the MENA region 186% (Lebanon), and in Europe 136% (Macedonia). As individual countries themselves determine the capacity of particular prisons, it is likely that data may understate the extent of the problem.

Decree of the President of the Italian Republic (D.P.R. for short) of April 12, 1990 n.75.

Law no. 241 of 31 July 2006.

Fall within these legislative measures: the law no. 199 of 26 November 2010, Decree law (D.L.) no. 211 of 22 December 2011 (i.e. ‘save prisons’, converted into Law no. 9 of 17 February 2012). The D.L. no. 78 of 03 July 2013 n. 78 (converted into law no. 94 09 August 2013), the D.L. no. 146 of 23 December 2013, converted into law no. 10 of 19 February 2014, the law no. 67 of 28 April 2014 (concerning the decriminalization of certain crimes), the Legislative decree (here in after D.L.G.) no. 28 of 16 March 2015, the law no. 47 16 April 2015 (modification of the measures related to personal precautionary measures) and, finally, legislative decrees no. 7 and 8 of 15 January 2016 (always related to the decriminalization of crimes) (see Capitta 2018).

The Decree law (d.l.) and the Legislative decree (d.l.g.) are both sources of law equal to the law, and are called acts having the force of law, both issued by Government. The main difference is that the Decree loses its effectiveness if it is not converted by the parliament into law within 60 days, while the Legislative decree is made by the Government, by virtue of a legislative delegation power received from the parliament.

Judgment given by the European Court of Human Rights in the Sulejmanovic case c. Italy (appeal No. 22635/03) of July 16, 2009, which sentenced the Italian State for the violation of art. 3 of the ECHR.

The reference is to the judgment of the European Court of Human Rights in the Torreggiani and other cases c. Italy (appeals No. 4357/09, 46882/09, 55400/09; 57875/09, 61535/09, 35315/10, 37818/10), issued on January 8, 2013, which sentenced the Italian State for the violation art. 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). Judgment given on the conditions of imprisonment of several prisoners in the prison of Busto Arsizio and Piacenza.

It is worthwhile bearing in mind that their effects are not perfectly identifiable and have passed, respectively, 9 and 8 years since they come into force.

An interesting topic of further investigation is the rate of recidivism of the convicts who benefited from the law 199/2010 and of the legislative decree 211/2011. Unfortunately, in order to study this phenomenon, microeconomic data concerning individual prisoners are indispensable.

Art. 61 n. 11 quater of the Italian Criminal Code.

The Surveillance Court is a judicial body provided for by the Italian penitentiary system to decide on requests for alternative sentences to imprisonment in jail presented by convicted persons in short sentences or prison sentences. Established by the law July 26, 1975, n. 354, deals with the granting and revocation of measures or penalties alternative to imprisonment in custody (ordinary and special probationary custody, semi-liberty, early release, home detention, conditional release, postponement of penalties). He also decides as a judge of appeal on measures taken by the supervisory magistrate, as attributed to the primary competence of the latter. The supervisory court has territorial jurisdiction over each district of the appeal court.

The struggle against the overcrowding of Italian prisons continued in subsequent years with the D.L. no. 78 of 2013 (entered into force on 22 June 2013, converted with amendments from law no. 98 of 9 August 2013), the limit of punishment for the application of pre-trial detention in prison passed from 4 to 5 years (articles 274, paragraph 1, letter c) and 280, paragraph 2, criminal procedural code). This law encouraged the use of the electronic bracelet as a way to control the prisoner under house arrest pursuant to article 275(a), paragraph 1, criminal procedural code. In 2013 the discipline of suspension of the order for execution of convicted sentences pursuant to art. 656 criminal procedural code, has been changed with the anticipated application of penalty discounts pursuant to article 54 of penitentiary rules; the condition of new penalty limits for the suspension of the execution order; and the modification of the conditions impeding the suspension, in a sense more favorable to the accused. Other legislative measures concerned the changes to article 47(b) (Home detention) penitentiary rules aimed at reducing the preclusions to access to prison benefits of repeated offenders, the assignment in test enlarged (Article 47, paragraph 3(a) by penitentiary rules), the stabilization of the enforcement of the sentence of the domicile referred to in Law n. 199 of 2010, the hypothesis of early release as per article 4 d.l. n. 146 of 2013, converted into law n. 10 of 2014. As a consequence of the law n. 67 of 2014, the application of the institution of probation for adults was extended (article 168(a) of the Criminal Procedural Code). As a result of Legislative Decree no. 28 of 16 March 2015 (which came into force on 02 April 2015), the institution has applied the particular tenuousness of the fact to adults and to the penal system falling in the jurisdiction of Judge of the Peace (Giudice di Pace a court that has jurisdiction over minor crimes). The measures to reduce the overcrowding of prisons are also included in the reform of the precautionary measures carried out by the law no. 47 of 2015 (passed in May 2015). Finally, as a result of legislative decrees no. 7 and no. 8 of January 2016, the decriminalization of certain types of crimes and the introduction of new hypotheses of criminal punishment.

In the event that all prisoners definitively convicted that they could potentially benefit from house arrest as an alternative to prison, the savings in terms of lower public spending for detention in the period 2011–2016 would be € 3,382,649,318.70. It was obtained by multiplying the number of prisoners definitively convicted of potential recipients of the law no. 199 of 2010, for the residual holding period for which the advance release is taken for the average daily cost per prisoner (calculated by the Ministry of Justice in € 123.78 to 2013.

The Index of Sustainable Economic Welfare (ISEW), develops MEW by adjusting GDP further by taking into account a wider range of harmful effects of economic growth, and by excluding the value of public expenditure on defence.

The list of 12 indicators and methodological issues are available at: https://www.istat.it/it/benessere-e-sostenibilità.

To counter the problem of cointegration between total prisoners and public expenditure in public order and social security, like partially proved by Glass (2009), the regressions are performed using the model of 2SLS, taking the natural logs of variables (for a similar approach see Barbarino and Mastrobuoni 2014; Levitt 1996).

That constitute the potential recipients of the measures introduced by the law no. 199 of 2010.

The twenty Italian regions possess a limited making power, but not in the area of criminal law. This means that the crimes and laws on house arrest of prisoners are the same within the borders of Italy.

Barbarino and Mastrobuoni (2014) used like instrumental variables the prisoners who took advantage of the pardon granted in Italy in 2006, when performing regressions using crime levels as dependent variable.

In Tables 5 and 6, where there is no problem of endogeneity between the dependent variable and the covariates, to exclude that the regional dimension is relevant, we have reported in the columns III and IV the results of the regressions performed using the fixed effects model (FE), taking into account that the detainees do not come from the same region in which they are imprisoned.

References

Barbarino, A., & Mastrobuoni, G. (2014). The incapacitation effect of incarceration: Evidence from several Italian collective pardons. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy,6(1), 1–37.

Barro, R. J. (1991). Human capital and growth. American Economic Review,91(2), 12–17.

Brandolini, A., & Carta, F. (2016). Some reflections on the social welfare bases of the measurement of global income inequality. Working Paper (Temi di Discussione) No. 1070-July 2016, Bank of Italy Rome.

Buonanno, P., Drago, F., & Galbiati, R. (2014). Response of crime to unemployment: An international comparison. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice,30(1), 29–40.

Buonanno, P., & Raphael, S. (2013). Incarceration and incapacitation: Evidence from the 2006 Italian collective pardon. American Economic Review,103(6), 2437–2465.

Capitta, A. M. (2018). Le misure alternative alla detenzione nel quadro della riforma Orlando: discontinuità virtuosa o riconferma del disordine normativo? Indice Penale,4(2), 297–332.

Drago, F., & Galbiati, R. (2012). Indirect effects of a policy altering criminal behavior: Evidence from the Italian prison experiment. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics,4(2), 199–218.

Drago, F., Galbiati, R., & Vertova, P. (2009). The deterrent effects of prison: Evidence from a natural experiment. Journal of Political Economy,117(2), 257–280.

Funke, G. S. (1985). The economics of prison crowding. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science,478, 86–99.

Giani, L. (2018). The evolution of Italian Penitentiary Legislation. Rehabilitation as an aim of sentencing and prisons. A possible combination? In E. Fransson, F. Giofrè, & B. Johnsen (Eds.), Prison, architecture and humans (pp. 309–329). Oslo: Cappelen Damm Akademisk.

Glass, A. (2009). Government expenditure on public order and safety, economic growth and private investment: Empirical evidence from the United States. International Review of Law and Economics,29(1), 29–37.

ISTAT. (2018). BES 2018. Il benessere equo e sostenibile in Italia. Rome: ISTAT.

Johnson, R., & Raphael, S. (2012). How much crime reduction does the marginal prisoner buy? Journal of Law and Economics,55(2), 275–310.

Jones, C. I., & Klenow, P. J. (2016). Beyond GDP? Welfare across countries and time. American Economic Review,106(9), 2426–2457.

Jorgenson, D. W., & Schreyer, P. (2017). Measuring individual economic well-being and social welfare within the framework of the system of national accounts. Review of Income and Wealth,63(s2), S460–S477.

Levitt, S. D. (1996). The effects of prison population size on crime rates: Evidence from prison overcrowding litigation. The Quarterly Journal of Economics,111(2), 319–351.

Nordhaus, W. D., & Tobin, J. (1972). Is Growth Obsolete? In W. D. Nordhaus & J. Tobin (Eds.), Economic research: Retrospect and prospect, volume 5, economic growth. New York: NBER.

OECD. (2013). OECD guidelines on measuring subjective well-being. Paris: OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264191655-en.

Romer, P. M. (1990). Human capital and growth: Theory and evidence. Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy,32, 251–286.

Stiglitz, J. E., Sen, A., Fitoussi, J. P., et al. (2009). Report by the commission on the measurement of economic performance and social progress. Paris: Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress.

United Nations. (2013). Handbook on strategies to reduce overcrowding in prisons. Criminal Justice Handbook Series. New York: United Nations.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the Editor, prof. Alain Marciano, to the two referees for their valuable advice and comments. I am deeply grateful to Dr. Fabio Bartolomeo for having allowed me to access the data on the composition of the prison population and ISTAT for the collaboration provided during the research and consultation of regional statistics. This research was carried out as part of the project of the “Observatory for monitoring the overall efficiency of the justice system and for the evaluation of the reforms necessary for the growth of the country”. I remain solely responsible for the opinions expressed in this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Di Vita, G. Recent legislative measures to reduce overcrowding of prisons in Italy: a preliminary assessment of their economic impact. Eur J Law Econ 49, 277–299 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10657-020-09639-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10657-020-09639-5