Abstract

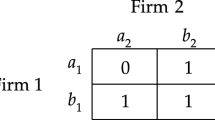

In this paper the case against the principal-agent modeling of most economic transactions is made about liberalizations of professional services that introduced in many European countries schemes of professionals’ remuneration contingent on outcomes—i.e. “contingent fees” for lawyers. If the relationship between the professional and clients is seen according to the principal-agent model, contingency fees can be economically justified. The case is quite different, however, if the situation is seen as one of authority under bounded rationality and unforeseen/asymmetrically gathered events. A game theoretical thought experiment aimed at checking the case for or against using agency models is carried out. It shows that (i) in the case of a self-interested professional, notwithstanding that overall utilitarian efficiency may be safeguarded, contingent fees leads to not respecting the fiduciary obligations (to detriment of Pareto optimality, impartial and loyal treatment of all clients, and the obligation to promote all the clients’ welfare). (ii) In the case of the professional’s willingness to comply with deontology standards—requiring impartial protection of all the clients’ rights and welfare, under a condition of minimal individual rationality—contingent fees lead nevertheless to making useless deontological motivations and to a loss of efficiency in utilitarian sense. A Pareto optimal, impartial, as well as efficient, arrangement aimed at maximizing the total volume of damage compensation is then considered. Nevertheless the main result is that, even if motivations to conform to such principles were available, under a contingent fee contract the professional could not carry out them because of the logic of the incentive contract. Thus, notwithstanding its widespread acceptance in the law and economics literature, agency theory seems not suitable in general for designing efficient and fair contracts and economic institutions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

This was one of the points of the heated debate that ensued the so called Bersani Act, the Italian decree law on the liberalization of professions, when it was passed in the Summer of 2006 (see dl. 223, July 4th, 2006, and the Law n. 248, August 4st 2006).

Some authors stresses a distinction between the US contingent fees system and what is called the UK-like conditional fees system. Under the second a lawyer gets an upscale premium only if the case is won, but the upscale premium does not vary in function of the adjudicated amount. These authors also compares the relative efficiency of two kinds of lawyers’ remuneration schemes, both conditional on outcome (see Emons 2004a, b; Emons and Garoupa 2005). However, whether in UK the premium is actually related to the amount adjudicated by the court is a matter of debate (Yarrow 2001). On the role of contingent fee in class action see Cassone and Ramello (2011) and Ulen (2011).

This is sometime argued not only ex post (after reform), but also “ideologically” ex ante, as the economic policy justification of their introduction in the legal system. For instance, consider that the so called 2006 Bersani Act in Italy introduced the principle that “professional’s remuneration should be contingent on results” in general for all the professions, and it has been based on the widespread acceptance amongst the policy analysts (but not the professionals) that professions must be run according to economic models suitable for the firm’s behavior, like as agency models.

A related but different point is raised by Emons (2000) who sees the client-lawyer relationship as a context of expertise and credence good.

On damages see also Cenini et al. (2011).

However, the literature also points out that (a) contingent fees risk raising prices of legal performances due to the lawyers’ possibility to renegotiate the percentage of compensation they obtained, after the client started a dependent relationship with them (lock-in effect) during the course of the case (Benson 1979; Swanson 1991); (b) conflict of interests between the lawyer and client could sharpen not about the effort in the single case, but about the lawyer’s decision about which case to litigate and which to accommodate through a transaction with the counterpart: in particular, the lawyer will choose the case to litigate within his portfolio so as to maximize his total returns and not his single clients’ satisfaction (Benson 1979; Schwartz and Mitchell 1970; Danzon 1983; Gravelle and Waterson 1993; Rickman 1994); (c) the effect of the contingent fees on social efficiency is uncertain concerning the total level of the judicial system’s tendency to litigation and on the extent of deterrence against hazardous behavior (that originate claims of damage compensations). In particular, proclivity of preventing such behaviors will be as greater as the lawyers’ opportunistic inclination to accommodate lower-income cases with rebating transactions. This depends on a parameter of identification between the lawyers’ and clients’ interests (Cooter and Rubinfeld 1989; Rickman 1994).

Economic models of reputation can be regarded differently (Fudenberg 1991). In this case, trust is represented by the probability a player—the client—assigns to the types of the second player—the professional—i.e. his reputation to be an honest type or, to say it differently, by the probability the professional identifies with a type that idiosyncratically follows a commitment. Under a reputation equilibrium (that is within an effective fiduciary relationship) the professional’s rational choice consists in sustaining her reputation by means of a behavior coinciding with the client’s expectations. We see that trust does not necessarily imply that the professional acts altruistically—this does not occur in reputation models—but it implies that client believes that the professional will follow a principle (Kreps 1990) or commitment to a rule of conduct. The reconstructing of reasons for which this happens can be both self-interest in the long run or intrinsic preferences for reciprocal conformity. The two different (but not incompatible) hypotheses are considered in Sacconi (2000, 2007) and Sacconi (2006), Grimalda and Sacconi (2005); Sacconi and Grimalda (2007).

It follows that, in order to overcome incompleteness of contracts, to take a full range of monetary payoffs (so to say form 1$ to ten millions), as if it was a complete set of possible outcomes separable from our limited knowledge of the unforeseeable states of the world, is not an allowed move. When some unforeseen state will be discovered the same amount of money will change its meaning as an outcome for the principal. Thus, it is not admissible what Maskin and Tirole suggested in they ad hoc reduction of incomplete contacts to a variant of the asymmetric information agency paradigm (Maskin and Tirole1999; Tirole 1999).

As references for fiduciary duties settled by professional demonologies and codes of professional ethics see Dzienkowski (1996), Dietrich and Roberts (1997), Koehn (1994). For an early discussion from an economist’s point of view of impacts of principal-agent oriented reforms of the legal profession over professional ethics see Mattews (1991).

References

Benson Sir, H. (1979). Final report of the royal commission on legal services (I & II), Cmnd 7648. London: HMSO.

Bowels, R. (1994). The structure of the legal profession in England and wales. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 10(1), 18–33.

Brickman, L. (2003). The continuing assault on the citadel of fiduciary protection: Ethics 2000’s revision of model rule 1.5. University of Illinois Law Review, 5, 1181–1216.

Cassone, A., & Ramello, G. B. (2011). The simple economics of class action: Private provision of club and public goods. European Journal of Law and Economics (forthcoming).

Cenini, M., Luppi, B., & Parisi, F. (2011). Incentive effects of class actions and punitive damages under alternative procedural regimes. European Journal of Law and Economics (forthcoming)

Cooter, R. D., & Rubinfeld, D. L. (1989). Economic analysis of legal disputes and their resolution. Journal of Economic Literature, 27, 1067–1097.

Dana, J., & Spier, K. (1993). Expertise and contingent fees: The role of asymmetric information in attorney compensation. Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization, 9, 349–367.

Danzon, P. M. (1983). Contingent fees for personal injury litigation. Bell Journal of Economics, 14, 213–224.

Davis, M. (1987). The moral authority of a professional code. In Pennok & Chapman (Eds.), Authority revised, NOMOS XXIX. NY: New York University Press.

Dietrich, M., & Roberts, J. (1997). Beyond the economics of professionalism. In J. Broadbent, M. Dietrich, & Roberts (Eds.), The end of the professions?. London: Routledge.

Dzienkowski, J. S. (Ed.). (1996). Professional responsibility standard, rules, statutes (1996–97 Edn). St.Paul, Minn: West Publishing Co.

Easterbrook, F. H., & Fischel, D. (1993). Contracts and fiduciary duties. Journal of Law & Economics, XXXVI, 425–451.

Emons, W. (2000). Expertise, contingent fees, and insufficient attorney effort. International Review of Law and Economics, 20, 21–33.

Emons, W. (2004a) Conditional versus contingent fees. Discussion Paper 04.09. University of Bern. www.vwi.unibe.ch/theory/papers/emons/ccfee.pdf.

Emons, W. (2004b) Playing it safe with low conditional fees versus being insuredby high contingent fees. Discussion Paper 04.19. University of Bern. www.vwi.unibe.ch/theory/papers/emons/lcf.pdf.

Emons, W., & Garoupa, N. (2005). US-style contingent fees and UK-style conditional fees: Agency problems and the supply of legal services. Managerial and Decision Economics, 27(5), 379–385.

Fehr, E., & Gächter, S. (2002). Do incentive contracts undermine voluntary cooperation? Institute of empirical research in economic, Working paper, University of Zurich. p. 34.

Fehr, E., & Schmidt, K. M. (2000). Fairness incentives ad contractual choices. European Economic Review, 44(4–6), 1057–1068.

Fher, E., Klein, A., & Schmidt, K. M. (2001) Fairness, incentives and contractual incompleteness. CESIFO Working paper. Munich. Germany. p. 445.

Flannigan, R. (1989). The fiduciary obligation. Oxford Journal of Legal Studies, 9, 285–294.

Frankel, T. (1998). Fiduciary duties. In P. Newman (Ed.), The new palgrave dictionary of economics and the law (Vol. II, pp. 127–132). London: McMillan.

Frey, B. (1997). Not just for the money. Brookfield: Edward Elgar.

Fudenberg, D. (1991). Explaining cooperation and commitment in repeated games. In J. J. Laffont (Ed.), Advances in economic theory, 6th world congress. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Geanakoplos, J., Pearce, D., & Stacchetti, E. (1989). Psychological games and sequential rationality. Games and Economic Behavior, 1, 60–79.

Gintis, H., Bowles, S., Boyd, R., & Fehr, E. (Eds.). (2006). Moral sentiments and material interests. Cambridge: MIT press.

Gravelle, H. S. E., & Waterson, M. (1993). No win, no fee: Some economics of contingent legal fees. The Economic Journal, 103, 1205–1220.

Grimalda, G., & Sacconi, L. (2005). The constitution of the not-for-profit organisation: Reciprocal conformity to morality. Constitutional Political Economy, 16(3), 249–276.

Grossman, S., & Hart, O. (1986). The costs and benefit of ownership: A theory of vertical and lateral integration. Journal of Political Economy, 94, 691–719.

Halpern, P. J., & Turnbull, S. M. (1983). Legal fees contracts and alternative cost rules: An economic analysis. International Review of Law and Economics, 3, 3–26.

Hart, O., & Moore, J. (1990). Property rights and the nature of the firm. Journal of Political Economy, 98(6), 1119–1158.

Koehn, D. (1994). The ground of professional ethics. London: Routledge.

Kreps, D. (1990). Corporate culture and economic theory. In J. Alt & K. Shepsle (Eds.), Perspectives on positive political economy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Maskin, E., & Tirole, J. (1999). Unforeseen contingencies and incomplete contracts. The Review of Economic Studies, 66(1) 226, 83–114.

Mattews, R. C. O. (1991). The economics of professional ethics: Should the professions be more like business? The Economic Journal, 1010, 737–750.

Rabin, M. (1993). Incorporating fairness into game theory and economics. The American Economic Review, 83(5), 1281–1302.

Raz, J. (1985). Authority and justification. Philosophy and Public Affairs, 14(1), 3–29 (Winter, 1985).

Rickman, N. (1994). The economics of contingent fees in personal injury litigation. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 10(1), 34–50.

Sacconi, L. (1999). Fondamento ed efficacia delle deontologie professionali. In Zamagni, S. (a cura di.), Le professioni intellettuali tra liberalizzazione e nuova regolazione. Milano: EGEA.

Sacconi, L. (2000). The social contract of the firm. Berlin: Springer.

Sacconi, L. (2006). CSR as a model of extended corporate governance, an explanation based on the economic theories of social contract, reputation and reciprocal conformism. In F. Cafaggi (Ed.), Reframing self-regulation in European private law. London: Kluwer Law International.

Sacconi, L. (2007). Incomplete contracts and corporate ethics: A game theoretic model under fuzzy information. In F. Cafaggi, A. Nicita, & U. Pagano (Eds.), Legal orderings and economic institutions. London: Routledge.

Sacconi, L., & Grimalda, G. (2007). Ideals, conformism and reciprocity: A model of individual choice with conformist motivations, and an application to the not-for-profit case. In P. L. Porta & L. Bruni (Eds.), Handbook of happiness in economics. London: Edward Elgar.

Salaniè, B. (1997). The economics of contracts. In Primer. A (Ed.), Cambridge Mass: The MIT Press.

Schwartz, M. L., & Mitchell, D. J. B. (1970). An economic analysis of the contingent fees and personal injury litigation. Stanford Law Review, 22, 1125–1162.

Simon, H. (1951). A formal theory of employment relationship. Econometrica, 19, 293–305.

Swanson, T. M. (1991). The importance of contingent fee arrangements. Oxford Journal of Legal Studies, 11, 193–226.

Tirole, J. (1999). Incomplete contracts: Where doe we stand? Econometrica, 67(4), 741–781.

Ulen, T. S. (2011). An introduction to the law and economics of class action litigation. European Journal of Law and Economics (forthcoming).

Yarrow, S. (2001). Conditional fees. Hume Papers on Public Policy, 8, 1–10.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sacconi, L. The case against lawyers’ contingent fees and the misapplication of principal-agent models. Eur J Law Econ 32, 263–292 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10657-011-9243-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10657-011-9243-x

Keywords

- Contingent fees

- Principal-agent

- Incomplete contracts

- Authority

- Professional ethics

- Fiduciary duties

- Conformist preferences