Abstract

In this paper, we focus on the institutional setting where Old Masters’Paintings (OMP) markets transactions are carried. We develop a preliminary attempt to embody legal provisions in econometric, hedonic pricing models. We consider a particular regulation applicable only in Italy, the “export veto” for art objects that are particularly relevant for the national cultural patrimony. We proxy such legal provision in order to include it in the statistical analysis and to check whether it affects the OMP price differentials between pre-auction estimated price and post-auction hammer price. Preliminary results show that the price differential is affected by the legal variable, therefore suggesting that the country’s institutional framework plays an important role in price dynamics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The puzzle of price formation for Old Masters Paintings (OMP) stems from the difficulties of applying the Marshallian theory of value to this particular market configuration and products. On one side, marginal utility—and thus demand factors—are not sufficient to define equilibrium price of paintings. Production costs, on the other side, are not able to settle any natural value underlying a painting.

In the literature, two alternative positions on OMP price determination coexist. The first one states that “the demand fluctuates widely, following collectors’ fads and manias and paintings prices are therefore inherently unpredictable” (Baumol 1986, p. 10). According to Baumol’s view, no fundamental value can therefore be identified for paintings. The opposite view assumes that some crucial issues can be detected in the market price, although a natural price linked to production costs does not exist for paintings (Frey and Pommerenhe 1989). According to this statement, market forces determine prices for art objects, as for any other economic good.

Following this second approach, the literature has recently focused on the mechanisms of price formation in the OMP markets and the on the methodologies aiming at building price indexes that valuate the profitability of investment in art. However, the heterogeneity of artworks; the institutional setting where transactions are carried; the monopolistic power held by the owner of the painting(s); the infrequency of trading, and the existence of different segments in the art markets, all constitute specific and problematic issues, linked to the determination and to the measurement of prices, the research still has to deal with.

In this paper, we take an “intermediate” approach. On the one hand, we believe that it should be possible to find a common structure that explains the determinants (or some determinants) of OMP price formation in art markets. On the other hand, we acknowledge the limitations and difficulties of the existing applied methodologies, and therefore, propose an integration of an existing approach. In particular, we focus on the institutional setting where art markets transactions are carried. We develop a preliminary attempt to embody legal provisions in empirical models. We consider a particular regulation applicable only in Italy, the “export veto” for art objects that are particularly relevant for the national cultural patrimony. We proxy such legal provision in order to include it in the statistical analysis and to check whether it affects the OMP price differentials between pre-auction estimated price and post-auction hammer price.

The paper is structured as follows: Sect. 2 surveys the economic literature and explains the paper’s motivation. Section 3 introduces the data, the used methodology and presents some of the main results. Section 4 concludes and paves the way for further research.

2 Literature survey and paper motivation

Our research focuses on the empirical study of art auctions, in particular OMP English auctions’ hammer prices. English auctions have, paradoxically, a Roman origin. Auction comes from Latin “auctio”, which means to ascend. The English auctions, in fact, sell art in an ascending price format.Footnote 1

Ashenfelter and Graddy (2003) state that the empirical study of art auctions has two purposes. On the one hand, the auction mechanism provides a public report on the prices of art objects. This information is the primary way that art objects are valued and it provides some primary information on preferences regarding art. However, because of the unique nature of many art objects, the interpretation of market prices requires great care.

On the other hand, art auctions provide data that may be used to test and refine strategic models of behaviour, and to understand the economic mechanism that drives a particular behaviour.

A broad stream of contributions attempts to understand how OMP prices, from (mostly) English art auctions, can be used to construct price indices. Auction prices, in fact, can be used to determine and compare price movements in other markets (i.e. stock markets) because, ideally, these prices reflect, the “true value” of a work of art, and are independent of the price discovery mechanism.

For the determination of price indices, at least four approaches have been developed:

-

i)

indices which reflect experts’ personal judgements (like the Sotheby’s Art Index);

-

ii)

indices based on the repeat sales regressions (see, among others, Locatelli-Bley and Zanola 1999; Pesando and Shum 1999; Mei and Moses 2003);

-

iii)

indices based on the average painting methodology, with its refinement of the representative painting (see Candela and Scorcu 1997);

-

iv)

indices based on hedonic regressions (see, among others, Buelens and Ginsburgh 1993; Chanel 1995; Agnello 2002).

Another stream of research attempts to capture the dynamics of the art items auctions. The auction institution itself, in fact, with commissions, experts, pre-sale estimates, reserve prices, national regulation and sequential sales can have a profound influence on the OMP price. The evidence on the role of estimates, for instance, appears to be divided. Some evidence (Ashenfelter 1989) indicates that auctioneers are simply trying to truthfully predict the price of a painting. Other evidence (Mei and Moses 2002) suggests that auctioneers may, in some cases, be altering the estimate from the true predicted value. Another example is the research in “the declining price anomaly”. Since Ashenfelter (1989) showed that prices are twice as likely to decrease as to increase for identical bottles of wine, sold in same lot sizes at auction, there has been a tremendous amount of study in the declining price anomaly in many types of art items auctions (for instance Pesando and Shum 1996; Beggs and Graddy 1997).

This paper starts from the second stream of research (about the auction institution itself) and analyses the impact of institutional set-ups (a particular legal provision in Italy) on the hammer price of OMP. We postulate that the Italian stringent regulation on exporting OMP would hinder market completion, thus, price formation of OMP, in Italy. The main hypothesis is that the OMP sold in Italy, would have a lesser price, measured in terms of percentage price differentials between pre-auction estimated and hammered price vis-à-vis the OMP sold outside Italy.

In this case, hedonic price methodology is not used in order to calculate indexes from the estimated coefficients, but in order to disentangle the implicit/shadow price of selected OMP characteristics, including the institutional setting.

3 Empirical analysis: data, methodology and results

The paragraph contains a description about the used datasets. It shows the reasoning explaining why a particular linear, “quasi-hedonic” model has been adopted for the empirical analysis. Finally, the paragraph presents and comments the main results.

3.1 Data

The structure of the art markets is rather complex. A first problem is related to the different organisation of the three main segments of the market. The primary market deals with the artist which personally sells his/her work to buyers, mainly art dealers. In the secondary market art dealers exchange paintings with collectors, mainly through galleries. Finally, the tertiary market is composed by auctions. These latter transactions are organised as sequential English auctions, where the item is sold to the highest bidder. The importance of the tertiary market is twofold. On one hand, this is the only segment for which we have an information structure that (partially) overcome the art’s typical problem of incomplete and asymmetric information. On the other hand, the share of the total market arising from auctions, data availability and reliability, and the evidence that this segment leads the secondary one (Candela and Scorcu 2001) make the price of this segment the benchmark where to test price structure and dynamics. The paper follows such considerations, by handling auction data only.

In this study we start from a database provided by a Milan-based company, Gabrius S.p.A.,Footnote 2 which gathers more than 200.000 OMP auctioned and sold world wide since 1990. The present work considers 3 different sub-datasets, constituted by German, Italian and British OMP from the 13th to the 19th century.Footnote 3 The Italian Masters dataset contains around 20.000 observations; the German Masters around 6000 and the British Masters around 4000.

For each observation, the 3 selected databases include, among other variables, code of the artist,Footnote 4 its nationality and period, title and code of the painting, date, city and house where the item has been auctioned, dimensions (in terms of length and height), lot number, genre, century, subject, material, support and level of attribution of the painting.Footnote 5 Moreover, the databases include information about whether the painting was quoted by the artistic literature, or was presented in exhibitions; whether it comes from a private collector or it has an expertise certificate. Finally, the databases contain information about pre-auction OMP estimated prices and post-auction hammer prices in 2002 U.S. dollars.

The sub-dataset that gathers “Italian Schools” OMP (from 13th to 19th century) contains 19.824 observations. Most of the paintings were sold by Sotheby’s and Christie’s in UK (44, 24%), U.S. (21, 30%) and Italy (19.19%). Most of the Italian OMP date back from the 18th (31.37%) and 17th (39.67%) centuries. The 92.15% of the sample is painted with oil; the 77.2% has a canvas support; the 16.39% is painted on a paper support. Most Italian OMP reproduce portraits (7.38%), still life (10.08%), and religious (32.80%) subjects.

More than half of the sample (57.20%) is attributed beyond any doubt to the considered author. The remaining percentage of the sample includes paintings not to be certainly attributed to the artist (studio of, circle of, after, manner of, school of). The 14.82% of the total sample has an expert certificate; the 6.18% was presented in art exhibitions; the 13.85% of the dataset is mentioned in the specialized literature and 14.41% comes from a private/public collection.

The sub-dataset that gathers “German Schools” OMP (from 13th to 19th century) contains 6.187 observations. Most of the paintings were sold by Sotheby’s and Christie’s in UK (43, 96%), U.S. (15, 10%), Germany (10.46%) and Austria (12.88%). Most of the German OMP date back from the 18th (47.79%) and 17th (28.17%) centuries. The 94.27% of the sample is painted with oil; the 57.43% has a canvas support; the 30.34% is painted on a paper support. Most German OMP reproduce portraits (16.18%), landscape (17.94%), and religious (18.52%) subjects.

More than half of the sample (64.05%) is attributed beyond any doubt to the considered author. The 16.42% of the total sample has an expert certificate; the 6.71% was presented in art exhibitions; the 14.98% of the dataset is mentioned in the specialized literature and 15.89% comes from a private/public collection.

The sub-dataset that gathers “British Schools” OMP (from 13th to 19th century) contains 3.990 observations. Most of the paintings were sold by Sotheby’s and Christie’s in UK (58, 07%), and U.S. (31, 88%). Most of the British OMP date back from the 18th (84.66%) centuries. The 82.60% of the sample is painted with oil; the 72.88% has a canvas support. Most British OMP reproduce portraits (41.40%) and landscapes (15.34%).

More than half of the sample (74.79%) is attributed beyond any doubt to the considered author. The 29.37% of the total sample has an expert certificate; the 16.37% was presented in art exhibitions; the 24.64% of the dataset is mentioned in the specialized literature and 32.61% comes from a private/public collection.

It is important to stress that the export veto holds for all those paintings that damage the historical cultural patrimony of Italy, despite the nationality of the author or the foreign provenience of the painting. This the reason why we perform our exercise on different, national and foreign Schools.Footnote 6

3.2 Methodology: the “quasi-hedonic” model

In the present work, we select a “quasi-hedonic”, linear regression model. We name it “quasi-hedonic” after the hedonic pricing methodology,Footnote 7 which represents the starting point of our empirical analysis, Hedonic pricing methodology has the advantage to allow for the estimation of a given painting’s value by adding the shadow prices of its characteristics.

In the study at issue, we can highlight two distinctive, original features. First, the attempt to operationalize a legal rule (the export veto) as a painting’s hedonic characteristic. Second our dependent variable is not the (logged) auctioned price, but the percentage difference between hammer price and pre-auction average estimated price. Therefore, we estimate an empirical model that explains (pre-auctioned estimated and hammer) price differentials as depending on a set of painting’s hedonic characteristics (shape, subject, material, level of attribution and so on) and on a particular institutional characteristic. We regress a “quasi-hedonic” model.

In order to empirically capture, at least part of, the “institutional approach”, we focus on a peculiar Italian provision that regulates OMP trading. Article 17 of the Italian Law no. 88/1998 totally forbids the export of art objects (without distinction between privately or publicly owned art objects), if the export damages the historical and cultural Italian patrimony.Footnote 8 (Article 17, paragraph 1, Law 88/1998: “If export damages the national historic and cultural patrimony, it is forbidden to export from the Italian Republic territory, those goods, which, according to Article 1 of the present Law and according to the Decree of the President of the Italian Republic, no. 1409, 30th September 1963, and subsequent modifications, are characterized by a particular nature; or belong to a peculiar historical and cultural milieu; and are of particular interest from the artistic, historic, archaeological, ethnographic, bibliographic, documentary or archivist point of view”).

Article 18 of the same regulation states that for those art objects for which Article 17 does not apply, the export is allowed, but after that the competent authority has released a free circulation permit.Footnote 9 (Article 18, paragraph 1, Law 88/1998: “Those who want to export cultural goods from the Italian Republic territory have to report to the competent authority, declare the good monetary value and apply for the export authorization. The authority will monetary value the good and concede or not the authorization. The authority decision has to be motivated”).

This particular Italian regulation (neither existing in other EU Member States, nor in the U.S.) introduces an export veto, that is, a particular institutional barrier to trade. The same law designs a very complicated procedure. In short, the OMP seller (auction houses, private collectors or art galleries) has to communicate the competent bureaus (Sovrintendenza dei Beni Culturali) his/her willingness to sell the object (internally or abroad). After an examination (lasting from 15 to 40 days) the bureau can (a) either decide that the OMP cannot exit the Italian Territory (and apply the export veto); (b) or decide to allow both national or international transaction and release an export permit. In the former case, the transaction can only occur in Italy and the art object must remain in the Italian territory. When the OMP is sold by auction houses, the authority notification of the veto might occur in the period between the pre-auction exhibitions and auction starting. Therefore, our crucial research question is: can the export veto affect OMP auctioned prices?

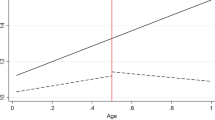

Our expectation is that the export veto negatively affects the hammer price of OMP auctioned in Italy. In order to operationalize and capture such legal effect, we compute DIFF, the percentage difference between hammer price and pre-auction average estimated price. After several checks, we select the following statistical “quasi-hedonic modelFootnote 10:

-

(1)

\( DIFF_{j,i,t} = \beta_{0} + \beta_{1} AUCSTATE_{j,i} + \beta_{2} YEAR_{j,t} + \beta_{3} MONTH_{j,t} + \beta_{4} OIL_{j} + \beta_{5} CANVAS_{j} + \beta_{6} SUBJECT_{j,i} + \beta_{7} 18CENTURY_{j} + \beta_{8} LITERATURE_{j} + \beta_{9} EXHIBITION_{j} + \beta_{10} EXPERTISE_{j} + \beta_{11} PROVENIENCE_{j} + \varepsilon_{j,i,t} \)

-

(2)

where AUCSTATE i,j is a dummy assuming the value of 1 if the painting has been sold in state i for every j-th observation, 0 otherwise. AUCSTATE can be considered a proxy to capture national legislation; it represents the assumption that if a OMP is auctioned and sold in a particular state territory, it will legally be disciplined by the regulation applicable in that nation.Footnote 11

-

(3)

YEAR j,t is a dummy assuming the value of 1 if the painting had been sold in year t, 0 otherwise; MONTH j,t is a dummy assuming the value of 1 if the painting has been sold in month t, 0 otherwise.

-

(4)

OIL is a dummy assuming the value of 1 if the painting is painted with oil and 0 otherwise; CANVAS is a dummy assuming the value of 1 if the painting is done on a canvas support and 0 otherwise. 18CENTURY is the dummy variable assuming the value of 1 if the painting was made in the 18th century and 0 otherwise.Footnote 12

-

(5)

SUBJECT i is a dummy assuming the value of 1 if the painting represents a particular subject i, 0 otherwise;

-

(6)

LITERATURE, EXHIBITION, PROVENIENCE and EXPERTISE are dummy variables taking the value of 1 when, respectively, the painting was quoted by the artistic literature; was presented in exhibitions; comes from a public/private collection; or it has an expert certification, stating that the painting is attributed to a particular Old Master, and 0 otherwise.

Finally, we add to the empirical, linear model a constant and an error term.

3.3 Empirical results

Table 1 shows the empirical results.Footnote 13 It is important to highlight that the estimated coefficients for Italy are always negative and statistically significant at 5% confident level, across the 3 different datasets. The negative sign of expected coefficients for Italy, across the three selected Schools, corroborates our idea that export veto might negatively affect auction dynamics, sales and hammered prices. The estimated coefficients magnitude, however, differ across Schools.Footnote 14

The relationship between price differential and the country where the OMP was hammered might have different, possible explanations. However, since the price mark-up presents negative estimated coefficients only for Italy, then we propose the following interpretation. The nation where the OMP is auctioned (and therefore, the legislation in force in that nation) might positively (or negatively) affect the mark-up on the pre-auction estimated prices. This result probably depends on the Italian legislation that introduces the export veto. The impossibility to export (and therefore sell to foreign buyers) the OMP decreases the demand size and the number of foreign bidders. Therefore, the mark up on the pre-auction estimated price is negative, since the export veto (for particular paintings) is communicated by the Italian authorities, in the period between the pre-auction exhibitions and the auction. Within this period, the estimated price of the item is communicated to potential buyers and/or published in the auction house catalogues (Table 2).

Other results can be highlighted, in particular, in reference to previous, hedonic studies. In Figini and Onofri (2005), for instance, the core of the empirical results is that OMP auctioned prices are affected by two main sets of variables: (1) variables that signal the authenticity (expertise, literature, and so on) of the object, which significantly increase the price; (2) idiosyncratic characteristics that reflect the high heterogeneity in the database and that can catch the bidder’s taste (painting’s subject, material, dimension, support, and so on).

The estimated coefficients for those variables that capture consumers’ taste and preferences present negative estimated coefficients for “standard”, very frequent characteristics of the OMP: oil, canvas, religious subject. In addition, not surprisingly and coherent with the above result, those OMP exposed in exhibitions have negative estimated price differentials. All this, might help “designing” the profile of OMP purchasers, consumers with “sophisticated” and mature taste, that are not willing to bid and pay more for “more common” products.

4 Conclusive remarks

The paper develops a preliminary attempt to embody legal provisions in empirical models. We consider a particular regulation applied in Italy, the export veto for fine arts objects, and we include such legal provision in the statistical analysis, proxied by the country in which the auction is held. Preliminary results show that the price differential between pre-auction estimated price and post-auction hammer price is affected, therefore suggesting that the country’s institutional framework plays an important role in price dynamics. Such evidence should pave the way for further research on the topic.

However, the results already allow for a short reflection on the spirit that drives the design and application of cultural regulations and policies. In particular, it is straightforward to link the Italian “export veto” regulation and the existence of diffused, parallel “black” Art Markets in Italy.Footnote 15

If we consider the Italian case, the legislator sets a veto for the export of a particular OMP (notified OMP).When a notified OMP is sold at auction, an odd legal situation might arise: the buyer acquires the art work ownership, but not its possession, if the export veto applies. To be more concrete: if a German citizen buys a notified OMP in Milan, he/she will become its owner. However, if the veto applies, the German citizen will never be able to export it from Italy. This ambiguous situation might discourage foreign purchasers from attending Italian auctions. More generally, a strict regulation might negatively affect the trade and, therefore, the price formation of Old Masters Paintings.

OMP illegal markets (‘black markets’) are markets where two particular types of demand and supply meet and interact. On the demand side, art collectors with a very price inelastic demand function, flexible budget constraint and well-defined preferences demand a product that is outside the legal market. The main driving force for OMP purchasers in black markets is ‘taste’, the pleasure of owning an important work of art or the work of an important and well-considered painter. However, OMP purchasers must be willing to consider the purchase as an investment. The existence of black markets is easily understandable when we look at our empirical results. Collectors usually have well-defined firm tastes and (sometimes lexicographic) preferences. They buy what they like; the OMP characteristics (whether a religious subject or a board support) and the well-known name of the painter (the regression for every sub-school suggests a strong effect on the auction price played by the artist and by the level of attribution attached to each item) affect the OMP purchase decision.

On the supply side, the sellers are mostly private collectors. However, sellers can also be traders who directly commission the stealing of art masterpieces from museums, or churches, or indirectly find stolen art objects. Other private collectors can be OMP suppliers too. Auction houses and fine-art dealers work as demand and supply ‘matchmakers’. They own private information about private collectors’ willingness to purchase and to sell and pass it on to the potential OMP traders. Auction houses and fine-art dealers have a strong monetary incentive to trade in black markets, because they receive a payment that represents a percentage on the OMP sale price. Given that, most of the time, seller and buyer never meet; the intermediaries can benefit from their informative advantages and extract a rent from the sale.

In economic terms, OMP illegal markets are efficient institutions for several reasons. First, they allow a reduction in the transaction costs that occur when the transaction is concluded on legal markets. Second, black markets allow the sale contract parties to implement a win–win strategy. The buyers can purchase the Old Masters they want for their private collection and for which they are willing to pay. Sellers can offer their Old Master and sell it with fewer transaction costs involved. Therefore, in an efficient perspective, black markets are transaction-cost minimizing institutions, for the implementation of which, procedures and art market regulation represent legal barriers. Besides these benefits, the main cost associated with black markets is a loss for society; loss in terms of a decrease in cultural offerings and trade. It is very difficult to suggest, design and implement policy solutions to OMP black markets. One possible solution could be opening up more markets to competitive dynamics. Whenever possible, the policy maker should design less onerous trading procedures or allow more Old Masters to enter the free market and, thereby, increase OMP supply. By rendering the trade easier and (sometimes) feasible and the markets less regulated, the black-market agents could come out into the open. The Italian “export veto” surely aims at protecting the national patrimony. Estimated coefficients show that the price mark-up for auction houses is negative when OMP transactions occurred in Italy. In our opinion, however, a “good” policy objective is implemented by a “bad” instrument.

Notes

Almost all OMP are auctioned in this ascending price format. Bidding starts low, and the auctioneer, subsequently calls out higher and higher prices. When the bidding stops, the object is said to be “knocked down” or “hammered down”. The final price is the “hammer price”. Not all items that have put up for sales and “knocked down” are sold. Sellers of individual items will set a reserve price, which is usually secret, and if the bidding does not reach these levels, the items will go unsold. In this case, unsold objects are said “bought in” by auctioneers.

For more information see www.gabrius.com.

From an artistic point of view, the most important problem in considering such a database relates to the fact that the OMP database includes very different artistic periods and schools. Identifying artistic schools and assigning each painter to one school is a difficult task. For the sake of simplicity, and without losing in generality, a first rough identification of the artistic schools is done by matching the (artistic) nationality of the painter with his/her period of life.

Unfortunately, the dataset does not contain the name of the artist. This is mostly due for privacy reasons.

In the database only the items whose price is greater than 2,500 dollars, at 1990 prices are included. The database, moreover, includes auctions held by the major international auction houses in the last 12 years. This selection should enable to reduce the weight of the marginal transactions that does not constitute the “core” of the market. For a complete statistical description of the database, see Candela et al. (2002).

Just an example. In Rome, in the Villa Borghese Park, is located the palace of Cardinal Giulio Borghese, who was an “aggressive” art collector, during the late Renaissance period. He was so eager to possess masterpieces of art, that he imprisoned Raffaello Sanzio, until the painter accepted to sell a painting to the Cardinal. Nowadays the Palace is a museum, destined to the conservation of Cardinal Borghese’s collection. In one of the most visited rooms, there is a beautiful Venus, painted by Raffaello, the apology of Italian, classical Renaissance art. Next to Raffaello’s Venus, there is another Venus, painted by Lucas Kranach the Elder. Even though the artist is German, and the paintings comes from Germany, the OMP belongs to the Italian cultural patrimony. If, hypothetically, that OMP were auctioned, the export veto would apply.

Whereas the use of hedonic models dates back to Court (1941), Lancaster (1971) and Griliches (1971), this methodology was used to analyse qualitative characteristics in the art market only recently by Frey and Pommerenhe (1989), Buelens and Ginsburgh (1993), Chanel et al. (1996), Agnello and Pierce (1996) and Agnello (2002), among others. The intuition behind the hedonic approach is that the (logged) price of an item can be decomposed into the price of an “average” item with average characteristics plus the prices of the deviations of the item characteristics with respect to their respective averages. Thus in the case of a painting, the price may be described by a simple linear regression such as:

$$ \ln p_{k,t} = \alpha_{0} + \sum\limits_{i = 1}^{N} {\alpha_{i} x_{i,k,t} } + \beta t + \varepsilon_{i,k,t} $$(1)where ln p k,t is the logarithm of price of painting k, with k = 1, 2, …, K sold at time t, with t = 1, 2, …, T, x i,k,t the ith (possibly qualitative) characteristics of the painting k (which may or may not depend on t, the year in which the painting is sold), ε k,t an error term and α and β are parameters. Obviously, within the same framework, more complex, non-linear model might be considered. In Eq. 1 t represents the exponential trend, which can be interpreted as the annual return of the generic item.

To compute annual price indices (and returns), regression (1) can be modified as follows:

$$ \ln p_{k,t} = \alpha_{0} + \sum\limits_{i = 1}^{N} {\alpha_{i} x_{i,k,t} } + \sum\limits_{t = 1}^{T} {\beta_{t} z_{t} } + \varepsilon_{i,k,t} $$(2)where z t is a dummy variable taking the value of 1 if the painting is sold in year t and 0 otherwise.

In the standard hedonic approach, after adjusting for the heterogeneity by considering artists—and paintings—specific variables, average prices are explained solely by the time. This allows the computation of price indices and rates of return from investment in art which are built on the β t coefficients.

“E’ vietata se costituisca danno per il patrimonio storico e culturale nazionale, l’ uscita dal territorio della Repubblica dei beni di cui all’articolo 1 della presente legge ed al decreto del presidente della Repubblica 30 settembre 1963, n. 1409, e successive modificazioni, che in relazione alla loro natura o al contesto storico e culturale a cui appartengono presentino interesse artistico, storico, archeologico, etnografico, bibliografico, documentale o archivistico”. Art. 17, comma 1, legge 88/1998.

“Chi intenda far uscire dal territorio della Repubblica beni culturali deve farne denuncia e presentarle a competenti uffici per l’esportazione, indicando contestualmente per ciascuno di essi il valore venale. L’ ufficio di esportazione, accertata la congruità del valore indicato, rilascia o nega, con motivato giudizio, l’ attestato di libera circolazione”. Art. 18, comma 1, legge 88/1998.

In our opinion, the selected model specification is the most efficient. Before selecting the model, we have regressed a linear hedonic model, where the dependent variable was the difference between hammered price and pre-auction estimated price. We have regressed the same model, the where the dependent variable was the logarithm of the difference between hammered price and pre-auction estimated price. However, we think that making the use of price percentage differentials, we can better control for the dataset heterogeneity.

As remarked by one referee, there are evidences from the literature that average price differences exist among different types of auction and auction houses. We have controlled for this cluster effect, since all auctions are English auctions and selected auctions at the same auction houses: Christie’s and Sotheby’s all over the world.

The dataset contains different support and material types. However, in order to minimise the heterogeneity of the dataset we select the variables with the highest frequency for respectively material, support and century.

Statistics diagnostics of the results was performed. In particular, we tested for heteroskedasticity with the Breusch-Pagan test that the econometric package STATA runs automatically, with a simple “hettest” command. However, our selected model specification allows us to minimize data heterogeneity (that could cause heteroskedasticity), by defining our dependent variable as a percentage price differential between hammered price and pre-auction estimated average price. Since the estimated coefficient present the expected signs and the R 2 values are not too high, we exclude heterosckedasticity.

Since the statistics diagnostics signal correct estimation procedures and results, even though R 2 are fairly low, we think that the different magnitudes in the estimated coefficients might capture, not only a possible export veto effect, but also buyers’ preferences and taste for the items of a particular School.

Source: website of Comando Carabinieri per la Tutela del Patrimonio Culturale (www.carabinieri.it/Internet/Cittadino/Informazioni/Tutela/Patrimonio+Culturale).

References

Agnello, R. J. (2002). Returns and risk for art: Findings from auctions of American paintings differentiated by artist, genre and quality, Mimeo. University of Delaware.

Agnello, R. J., & Pierce, R. (1996). Financial returns, price determinants and genre effects in American art investment. Journal of Cultural Economics, 20(4), 359–383.

Ashenfelter, O. C. (1989). How auctions work for wine and art. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 3, 13–26.

Ashenfelter, O. C., & Graddy, K. (2003). Auctions and the price of art. Journal of Economic Literature, 3, 763–787. doi:10.1257/002205103322436188.

Baumol, W. J. (1986). Unnatural value: Art as investment as a floating crop game. The American Economic Review, 76, 10–14.

Beggs, A., & Graddy, K. (1997). Declining values and the afternoon effect: Evidence from art auction. The Rand Journal of Economics, 28, 544–565. doi:10.2307/2556028.

Buelens, N., & Ginsburgh, V. (1993). Revisiting Baumol’s unnatural value, or art as investment as a floating crop game. European Economic Review, 37, 1351–1371. doi:10.1016/0014-2921(93)90060-N.

Candela, G., Figini, P., & Scorcu, A. (2002). Hedonic prices in the art market: A reassessment. Paper presented at ACEI Conference, Rotterdam, 13–15th June 2002.

Candela, G., & Scorcu, A. E. (1997). A price index for art market auctions. Journal of Cultural Economics, 21, 175–196. doi:10.1023/A:1007442014954.

Candela, G., & Scorcu, A. E. (2001). In search of stylized facts on art market prices: Evidence from the secondary market for prints and drawings in Italy. Journal of Cultural Economics, 25, 219–231. doi:10.1023/A:1010956416307.

Chanel, O. (1995). Is the art market behaviour predictable? European Economic Review, 39, 519–527. doi:10.1016/0014-2921(94)00058-8.

Chanel, O., Gerard-Varet, L. A., & Ginsburgh, V. (1996). The relevance of hedonic price indices: The case of paintings. Journal of Cultural Economics, 20(1), 1–24.

Court, L. (1941). Entrepreneurial and consumer demand theories for commodities spectra. Econometrica, 9, 135–162. and 241–97.

Figini, P., & Onofri, L. (2005). Old masters paintings: Price formation and public policy implications. In A. Marciano & J. M. Josselin (Eds.), Law and the state: A political economy approach (pp. 381–398). Edward Elgar Publisher.

Frey, B. S., & Pommerehne, W. W. (1989). Muses and markets: Explorations in the economics of the arts. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Griliches, Z. (1971). Price indexes and quality changes: Studies in new methods of measurement. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lancaster, K. (1971). Consumer demand: A new approach. New York: Columbia University Press.

Locatelli-Bley, M., & Zanola, R. (1999). Investment in painting: A short-run price index. Journal of Cultural Economics, 3.

Mei, J., & Moses, M. (2002). Are investors credulous? Some preliminary evidence from art auctions, Mimeo. Stern School, NYU.

Mei, J., & Moses, M. (2003). Art as investment and the underperformance of masterpieces: Evidence from 1875–2002. The American Economic Review, 92, 1656–1668. doi:10.1257/000282802762024719.

Pesando, J. E., & Shum, P. M. (1996). Price anomalies at auction: Evidence from the market for modern prints. In V. Ginsburgh & P. M. Menger (Eds.), Economics of the arts: Selected essays (pp. 113–134). Elsevier Publisher.

Pesando, J. E., & Shum, P. M. (1999). The returns to Picasso’s prints and to traditional financial assets, 1977 to 1996. Journal of Cultural Economics, 23, 182–192. doi:10.1023/A:1007595305661.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Paulo A.L.D. Nunes, Paolo Figini, Antonello E. Scorcu and the participants of the IVth Corsica Workshop in Law and Economics, Bruno Frey in particular, for suggesting insightful points. I would also like to thank Daniele Liberanome (Gabrius S.p.A.) for the dataset provision and an anonymous referee for suggesting insightful points. The usual caveats apply.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Onofri, L. Old master paintings, export veto and price formation: an empirical study. Eur J Law Econ 28, 149–161 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10657-008-9094-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10657-008-9094-2