Abstract

Functional Disorders (FD) refer to persistent somatic symptoms caused by changes in the functioning of bodily processes. Previous findings suggest that FD are highly prevalent, but overall prevalence rates for FD in European countries are scarce. Therefore, the aim of the present work was to estimate the point prevalence of FD in adult general populations. PubMed and Web of Science were searched from inception to June 2022. A generalized linear mixed-effects model for statistical aggregation was used for statistical analyses. A standardized quality assessment was performed, and PRISMA guidelines were followed. A total of 136 studies were included and systematically synthesized resulting in 8 FD diagnoses. The large majority of studies was conducted in the Northern Europe, Spain, and Italy. The overall point prevalence for FD was 8.78% (95% CI from 7.61 to 10.10%) across Europe, with the highest overall point prevalence in Norway (17.68%, 95% CI from 9.56 to 30.38%) and the lowest in Denmark (3.68%, 95% CI from 2.08 to 6.43%). Overall point prevalence rates for specific FD diagnoses resulted in 20.27% (95% CI from 16.51 to 24.63%) for chronic pain, 9.08% (95% CI from 7.31 to 11.22%) for irritable bowel syndrome, and 8.45% (95% CI from 5.40 to 12.97%) for chronic widespread pain. FD are highly prevalent across Europe, which is in line with data worldwide. Rates implicate the need to set priorities to ensure adequate diagnosis and care paths to FD patients by care givers and policy makers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Functional disorders (FD), characterized by persistent (somatic) symptoms such as fatigue, dizziness, bowel symptoms, or neurological dysfunctions, are highly prevalent in all medical settings [1]. An overlap of multiple symptoms in patients is associated with an impaired health status [2,3,4]. Patients with FD suffer from a reduced quality of life [5], high work disability and illness worries [6]. Furthermore, they cause an increase of health care costs [7] compared to the general population [6].

FD were originally subsumed under the chapter of hysteria and later defined by the absence of organic explanations. Nowadays the role of psychological factors in their onset, worsening, or maintenance is recognized [8]. Functional somatic symptoms have been labeled as “medically unexplained symptoms”, which use has been criticized [9]. The latter clusters chronic somatic symptoms without reproducibly observable pathophysiological mechanisms [10]. The current taxonomy for mental disorders, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders—DSM [11], subsumes FD under Somatic Symptom Disorder with the attempt to emphasize positive symptoms such as somatic symptoms with abnormal thoughts, feelings, and behaviors in regard to those symptoms [12]. The commonly used taxonomy of the International Classification of Diseases—ICD [13]—includes FDs under different categories, for instance the rubric of mental disorders with (un-) differentiated somatoform disorders, chronic pain (CP), irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS), or fibromyalgia (FM). There is an ongoing discussion about the criteria for diagnosis, as shown by the introduction of the Somatic Symptom Disorders (SSD) of the DSM-5 [12] and the Bodily Distress Disorders of the ICD-11 beta draft classification [14], which both led to a controversy about the capture of different dimensions. On the one hand specific features such as distress or excessive thoughts and behaviors have to be present, on the other hand the definitions strive for an absence of features like for instance physical or medical causes [15]. Another diagnostic system, the Diagnostic Criteria for Psychosomatic Research (DCPR), includes FD under the chapter of persistent somatization, conversion symptom, or somatic symptoms secondary to a psychiatric disorder [16, 17]. New concepts, such as the bodily distress syndrome, were developed [18] and demonstrated to be useful [19].

Discussions regarding diagnostic criteria are open for some FD labels (e.g., IBS [20, 21], CP [22]). For instance, Manning introduced diagnostic criteria for IBS in 1978 [23] while the Rome Foundation published [20] the Rome criteria in 1989. Within each diagnostic system update [24, 25], major changes were introduced. Manning modified the number of symptoms needed for the diagnosis of IBS and in Rome’ revisions defecation patterns were added [25]. A higher sensitivity and accuracy was observed for Manning when compared to Rome criteria [26] but Rome-revision IV became the gold-standard for diagnosing [27]. Similarly, CP diagnostic criteria were defined based on DSM, ICD, or the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) systems, even though they differed regarding the time criterion. Indeed, the majority of currently available studies refers to a 6-month duration of pain while a minority refers to a 3-month duration (i.e., those using DSM-5, and ICD-11). For FM, there is, in contrast, a high scientific consensus [28, 29].

Due to this inconsistent use in nosography, point prevalence for FD varies widely, also when applied to specific diagnosis (e.g., CP, IBS, CFS). A lack of reviews summarizing the European epidemiological data of FD is also evident. Hence, the present work has the aim to fill in this gap by systematically reviewing the literature on prevalence of functional disorders in the adult general population across Europe. Since distinct FD are widely overlapping in the general population [30, 31], an overall point prevalence of FD is presented. Additionally, an overall point prevalence of specific diagnoses according to the common nosology and an overall point prevalence in regard to the European country as well as both for specific disorder and country are estimated.

Methods

Eligibility criteria

English articles published in peer-reviewed journals on prevalence of FD in European adults (i.e., ≥ 18 years of age) were included. The outcome had to refer to FD point prevalence [32] diagnosed according to the DSM, ICD, DCPR, or standardized criteria (e.g., Manning, Rome, American College of Rheumatology [ACR]) also via self-developed questionnaires if referring to specific standardized criteria. Additional inclusion criteria were: observational design (e.g., cross-sectional, longitudinal, cohort, case–control); general population; sample size of at least 500 subjects, to minimize under- or over-estimation of prevalence and to ensure the inclusion of high-quality research [33, 34] and guarantee statistical robustness [35, 36]. Sex-specific populations were accepted for the systematic review, but were not included in meta-analyses. Studies focusing on special populations (e.g., veterans, students), qualitative studies, and randomized controlled trials were excluded.

Information sources and search strategy

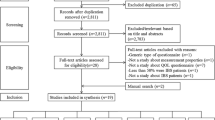

A systematic search in PubMed and Web of Science was conducted from inception to June 2022. Search terms were any term of FD (for details see Table S2, online supplementary material) combined using the Boolean ‘AND’ operator with ‘Prevalence*’ ‘OR’ and ‘Epidemiol*’. The full search strategy for PubMed is presented in Table S2 (online supplementary material). A manual search of reference lists and a targeted search of grey literature was performed. The review process was streamlined by using the open source online tool Rayyan [37]. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) guidelines [38] were followed. Endnote [39] was used to remove duplicates. Authors were contacted to provide their reports if the full text could not be retrieved. Two reviewers (CR and GM) independently screened potential eligible articles and full-texts, and a third reviewer (FC) was included in case of disagreements. The protocol was preregistered on PROSPERO no. CRD42022298974) [40], as well as on OSF (https://osf.io/w52jm).

Data extraction and quality assessment

A standardized data extraction form was developed to collect relevant data: reference, population, sample size, study design, diagnostic procedure (diagnostic instrument, additional clinical interview), prevalence estimates. After data extraction, studies were grouped according to specific diagnosis (e.g., IBS, CP, CFS). The methodological quality of studies was verified independently by CR and GM via the Joanna Biggs Institutes’ Critical Appraisal Checklist for Studies Reporting Prevalence Data (JBI) [41]. The JBI [41] assesses study quality via nine items to explore: study participants, sample size, sample power, methods, measurement, statistical analysis, response rate [41]. It allows to collect information based on a 4-point Likert scale (“yes, no, unclear, not applicable”) giving a maximum sum score of 9 [42]. Sum score was converted into percentage; over 66% were considered as low, between 44 and 65% as moderate, < 44% as high risk of bias. The Kappa coefficient statistic for interrater reliability showed a very good outcome with 0.91 [43].

Statistical analysis

If not available in the paper, the point prevalence was calculated, i.e., (number of diagnosed participants/total sample number) × 100. To ensure robustness in case of multiple prevalence estimates collected over time, the first report obtained in the first assessment was used and no studies overlapped regarding the recruitment of patients. Data were analyzed using the Software R Studio (version 4.3.0) with the R function metaprop from R package meta (package version 6.2.1.). Data and R syntax are available on OSF (https://osf.io/w52jm). An overall point prevalence rate for FD was calculated using a generalized linear mixed-effects model (GLMM) [44] which logit-transforms proportions [36]. All studies were included in the overall point prevalence calculation. Thereafter, subgroup analyses for specific diagnoses (i.e., IBS, CP with a 6-month duration, CWP), for specific country (i.e., Denmark, France, Germany, Great Britain, Italy, Netherlands, Norway, Spain, Sweden), and a post-hoc analysis regarding the use of validated questionnaires (validated vs. non-validated) were conducted based on a mixed-effects model [36]. In order to be rigorous, these subgroup analyses were run if there was a minimum of 10 studies per group [36]. Additional post-hoc subgroup analysis was conducted for specific diagnosis in regard to each country if there were at least two studies per diagnosis. A subgroup analysis was conducted for the risk of bias including low and moderate risk of bias studies after JBI-rating. The between-study heterogeneity was explored by calculating τ2 with a Maximum-likelihood estimator [45] as well as via I2-, Q-statistics, and the prediction intervals [46]. Results are reported with 95% Confidence Intervals (CI) assuming a Clopper-Pearson distribution and displayed using forest plots. To examine symmetry and publication bias, Egger’s test and Peters’ regression test were run and a funnel plot of logit transformed proportions was created. Forecast analyses were conducted using meta-regressions with a mixed-effects model to examine whether the year of publication might predict FD point prevalence.

The current study is part of the innovative training network ETUDE (Encompassing Training in fUnctional Disorders across Europe; https://etude-itn.eu/), ultimately aiming to improve the understanding of mechanisms, diagnosis, treatment and stigmatization of Functional Disorders [47].

Results

Results of the systematic review

After removal of duplicates, 74,733 articles from databases and 220 from citation searching were screened for eligibility, among them 707 full-text articles were assessed. A total of 136 papers met the inclusion criteria (see Fig. S1, online supplementary material) with 199 point prevalence rates referring to 8 FD diagnoses: headaches (n = 3), CFS (n = 7), somatization (n = 8), FM (n = 11), CWP (n = 18), IBS (n = 35), CP (n = 24), and functional gastrointestinal, neurological, psychiatric symptoms (n = 30) (see Table S1, online supplementary material).

Point prevalence estimates of FD

In total, 199 point prevalence estimates were found ranging from 0.03% for CFS [48] to 62.5% in females with IBS [49].

Headaches

Three studies on tension type headaches [50,51,52,53] reported rates of 13.3% [51], 18.7% [52], and 34% [53], respectively. Kristiansen et al. [52] and Göbel et al. [51] used Norway registers of selected counties while Sjaastad et al. [53] analyzed a rural general population.

Chronic fatigue syndrome/Myalgic encephalomyelitis

Seven studies reported prevalence rates up to 8.1% [30, 64,65,66,67,68,69]. Variations in prevalence rates were found due to the definition of CFS with the higher rates (0.19%) applying the Centers for Disease Control criteria and the lowest rates (0.03%) applying the Epidemiological Case Definition [48].

Somatization

Eight studies [54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61] reported point prevalence from 0.6 [61] to 35.9% [62]. Overall the studies applied different diagnostic criteria: DSM [54, 56, 57, 59, 60, 63], ICD [61, 62], both ICD/DSM [58]. Among them, Grabe et al. [55] estimated the point prevalence using the DSM-IV with 1.3% for specific somatoform disorder and 19.7% for undifferentiated somatoform disorder.

Fibromyalgia

Eleven studies [30, 68, 70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81] reported rates between 0.66 [72] and 4.6% [30]. Two studies that used all-female samples had higher rates (10.5%, [71]; 13.5%, [75]). Twelve studies [71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81] applied the ACR 1990 criteria for diagnosing FM showing a prevalence with a range from 0.66 [72] to 13.5% [75]. Mäkelä et al. [70] used the Yunus criteria with prevalence estimates of 0.75%, while Janssens et al. [68] used DSM-IV and ICD-10 resulting a point prevalence of 3%. In some cases, the authors conducted a clinical examination only in a subgroup of the sample and the prevalence rate was calculated on this subgroup. This diagnostic procedure was applied in several studies [71,72,73, 75, 76, 78, 79] with prevalence rates around 0.75% and 2.4%. The highest prevalence estimates (i.e., 3% and 4.6%) were found when no clinical examinations were conducted [68, 69].

Chronic widespread pain

Eighteen studies [3, 30, 66, 73, 82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95] provided information on prevalence showing a range from 1.42% [95] up to 20.8% in an all-female twin sample [93]. Applying ACR-1990 criteria [3, 30, 66, 73, 82, 85,86,87,88,89,90, 92,93,94, 96], prevalence rates were higher (up to 20.8% [93]) than referring to other criteria (e.g., DSM-IV: 6.7% [91], Manchester: 4.7% [83], others: 1.42% [95]).

Irritable bowel syndrome

Point prevalence estimates ranged from 2.1% [97] up to 62.5% [49] with a broader IBS-definition in an all-female sample. Heterogeneity in prevalence seems related to the classification system used (e.g., Manning or Rome criteria) and the procedure applied for the assessment. When Rome I criteria were used [97,98,99,100,101,102,103], rates were lower than when Manning was used [97, 100]. When Rome II criteria were applied, prevalence was lower than when Manning or Rome I was applied [98]. When Rome IV was used, rates were lower than with Rome III [104].

When a clinical interview was proposed next to self-administered questionnaires [97, 98, 105,106,107], point prevalence was lower [49, 97, 98, 105,106,107] than when the clinical interview was not conducted [104, 108].

Chronic pain

In 12 studies [109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120], pain was measured independently of the body region. Rates ranged from 14.3 [110] to 40% [109, 114]. The range might be this wide due to the heterogeneity of pain regions that were examined. Six studies reported on low back pain with a prevalence of 10–27% [91, 121,122,123,124,125,126], 4 studies reported on musculoskeletal pain (23.9–45% [127,128,129,130]), 3 on pelvic pain (17–26.8% [131,132,133]), 3 on neck pain (9–22%, [134,135,136]), 1 on chest pain (44.7% [137]), and 1 on abdominal pain (22.6% [138]).

Functional gastrointestinal, neurological or psychiatric symptoms

Thirty studies derived through a miscellaneous group of functional gastrointestinal, neurological or psychiatric symptoms. They are described in Table S1 (online supplementary material).

3.11. Results of the meta-analyses and subgroup analyses

Overall point prevalence

The meta-analyses of 199 estimates including 2.448.164 observations resulted in an overall point prevalence of 8.78% (95% CI from 7.61 to 10.10%) (see online supplementary material Fig. S2). A significant heterogeneity was found (I2 = 99.9%, prediction interval [0.1; 0.46]) as well as asymmetry in the funnel plot, Egger’s test (t(197) = − 10.14, p < 0.001) and Peters’ regression test (t(197) = − 4.82, p < 0.001) (see Figs. S1 and S2, online supplementary material).

Overall point prevalence for specific diagnoses

The overall point prevalence for CP resulted in 20.27% (95% CI from 16.51 to 24.63%), for IBS in 9.08% (95% CI from 7.31 to 11.22%), and for CWP in 8.45% (95% CI from 5.40 to 12.97%). The subgroup analysis of IBS, CP, and CWP included 89 prevalence estimates with 1.156.402 subjects and resulted in a significant between groups difference with Q(2) = 36.38, p < 0.001 (see Fig. 1).

Forest plot of the overall point prevalence rates for IBS, CP, and CWP with 95% confidence intervals and prediction intervals in regard to the author, year of publication, and country. Note. AT Austria, BE Belgium, BG Bulgaria, CH Switzerland, DE Germany, DK Denmark, ES Spain, FI Finland, FR France, GB Great Britain, HR Croatia, IE Ireland, IT Italy, NL The Netherlands, NO Norway, PL Poland, SE Sweden

Overall point prevalence per country

The meta-analyses showed the highest overall point prevalence of FD in Norway with 17.68% (95% CI from 9.56 to 30.38%) and the lowest in Denmark with 3.68% (95% CI from 2.08 to 6.43%). Most studies were conducted in Sweden (N = 27), followed by Great Britain (N = 22), Spain (N = 20), Germany (N = 17), France and Denmark (each N = 15), Italy, Netherlands (each N = 13), and Norway (N = 12). The subgroup analysis showed a significant between groups difference with Q(8) = 27.34, p < 0.001, including 154 prevalence estimates and a total of 2.290.761 observations (see Fig. 2).

Forest plot of the overall point prevalence of function disorders in regard to the country (with a number ≥ 10 studies per country) with 95% confidence intervals and prediction intervals in regard to the author, year of publication, and specific diagnosis. Note. CP Chronic pain, CFS Chronic fatigue syndrome, CWP Chronic widespread pain, FBLO Functional bloating, FBOW Functional bowel symptoms, FCON Functional constipation, FDIAR Functional diarrhea, FDYS Functional dyspepsia, FM Fibromyalgia, IBS Irritable Bowel Syndrome, LBP Low back pain, PAIN musculoskeletal pain, PP Pelvic pain, SOM Somatization, TTH Tension type headaches, WAD Whiplash associated disorder

Overall point prevalence for specific diagnosis regarding each country

The overall point prevalence for specific diagnosis varied according to the country. For IBS, the overall point prevalence was in France 4.09% (95% CI from 2.18 to 7.52%), in Germany 5.51% (95% CI from 1.19 to 22.01%), in Spain 7.42% (95% CI from 3.67 to 14.45%), in the Netherlands 6.83% (95% CI from 3.56 to 12.68%), in Poland 7.26% (95% CI from 0.03 to 96.05%), in Denmark 8.03% (95% CI from 2.30 to 24.44%), in Finland 8.24% (95% CI from 3.79 to 17.02%), in Great Britain 11.12% (95% CI from 1.23 to 55.69%), in Sweden 13.13% (95% CI from 9.26 to 18.31%), and in Italy 14.58% (95% CI from 4.08 to 44.66%). The overall point prevalence for CP resulted in 15.85% in Germany (95% CI from 6.90 to 32.38%), 16.80% in Spain (95% CI from 8.16 to 31.47%), 22.28% in France (95% CI from 0.37 to 95.60%), 26.67% in Italy (95% CI from 16.61 to 39.91%), 27.64% in Sweden (95% CI from 0.26 to 98.27%), and 33.22% in Norway (95% CI from 14.68 to 58.99%). The overall point prevalence of CWP was in Sweden 6.17% (95% CI from 1.97 to 17.73%) and in Great Britain 10.41% (95% CI from 5.47 to 18.92%). The analysis showed an overall prevalence for FM of 1.81% in Denmark (95% CI from 0.00 to 99.42%) and of 2.42% (95% CI from 1.85 to 3.18%) in Spain. In Germany, the overall prevalence of somatization was 9.13% (95% CI from 0.50 to 66.65%) and in Spain was 25% (95% CI from 5.17 to 67.09%). The overall prevalence of CFS was 1.19% in the Netherlands (95% CI from 0.36 to 3.83%) and 7.41% in Denmark (95% CI from 1.48 to 29.84%). For more details see the online supplementary material (see Fig. S3 online supplementary material).

Overall point prevalence according to validation or non-validation of tools used

Seventy-nine studies used a validated tool with an overall point prevalence of 10.19% (95% CI from 8.17 to 12.64%) while 119 studies used non-validated tools with an overall point prevalence of 7.85% (95% CI from 6.51 to 9.44%). Non-significant effects was found between groups (Q(1) = 3.25, p = 0.071).

Forecast analyses

Using the prevalence data with the year of publication, findings indicate a significant yearly decrease of 3.58 (95% CI − 5.43%; − 1.73%) for FD point prevalence.

Risk of bias analysis

For the meta-analysis on point-prevalence, 166 studies showed a low risk of bias with an overall point prevalence of 8.01 (95% CI from 6.83 to 9.38%), and 33 a moderate risk of bias with an overall point prevalence of 13.66 (95% CI from 10.31 to 17.90%). The subgroup-analysis resulted in a significant between groups effect (Q(1) = 11.02, p < 0.001). Studies with high risk of bias were not included in the meta-analysis.

Discussion

The present systematic review and meta-analyses of the literature on FD point prevalence in adult European populations revealed a wide range from 0.66% for FM up to 62.5% for IBS. The meta-analytic aggregation resulted in an overall point prevalence of FD of 8.78% (95% CI from 7.61 to 10.10%). Prevalence rates of FD were highest in Norway with 17.68% (95% CI from 9.56 to 30.38%) and lowest in Denmark with 3.68% (95% CI from 2.08 to 6.43%). The majority of epidemiological studies was found in Northern European countries, Spain, and Italy. The overall point prevalence rate of CP was 20.27% (95% CI from 16.51 to 24.63%), IBS showed a rate of 9.08% (95% CI from 7.31 to 11.22%), and CWP a rate of 8.45% (95% CI from 5.40 to 12.97%).

The distribution of prevalence estimates according to the systematic review was in some cases homogeneous within the same diagnosis (e.g., CFS, FM), in other cases heterogeneous (e.g., somatization, CWP, IBS, CP). This seems to be based in differences in the diagnostic system used (e.g., DSM vs ICD or Manning vs Rome), in the assessment procedures applied (e.g., validated tools vs. non-validated tools, adding a clinical interview), and in the country in which data were collected. To diagnose a specific FD, not only different diagnostic systems were applied (e.g., ICD and DSM for somatization, Manning and Rome for IBS, and ICD, DSM and IASP for CP) but also different revised versions of the system itself were used (e.g., ICHD version 1–4 for headaches, Rome version 1–4 for IBS [139]). To the best of our knowledge, there is a research gap concerning common nosology of FD terms’ impact on epidemiological outcomes. In particular, heterogeneity in prevalence rates for specific FD diagnoses (e.g., headaches, CP, CWP, IBS) implicates that prevalence rates differ in regard to the custom taxonomy and criteria used. Finding the “true” prevalence of FD requires a precise methodological design applying standardized criteria. This might include the assessment methods for diagnosing. For IBS and FM, common assessment methods were applied across the studies reviewed: self-administered questionnaires, (personal or telephone) clinical interviews or examinations, and their combination [216]. Findings of the systematic synthesis resulted in a lower point prevalence when a clinical interview or examination was applied instead of studies using a self-administered questionnaire as diagnostic tool. When validated tools were applied, the overall point prevalence was higher compared to the application of non-validated instruments. Findings are in line with an investigation on Danish adult FD patients, showing higher prevalence rates when a self-report tool was applied in comparison to when clinical interviews were conducted [140]. Wide ranges in prevalence rates were described across several (psycho-)somatic disorders, leading to the conclusion that there is a need for a common scientific practice applying uniform methodological validated assessment tools to ensure comparability of results.

Although there is heterogeneity of results, the overall point prevalence for all FD combined was 8.78% (95% CI from 7.61 to 10.10%). This is the first study to provide a quantitative synthesis of epidemiological results on the general population across Europe. Globally, the prevalence of FD in the general population was estimated at 12.9% (95% CI from 12.5 to 13.3%, applying the SSD criteria) [141]. In the primary care context with a worldwide perspective, epidemiological investigations using metanalytic aggregations revealed slightly lower overall point prevalence rates for the somatization disorder with a range from 0.8% (95% CI 0.3–1.4%, I2 = 86%) to 5.9% (95% CI 2.4–9.4%, I2 = 96%) and higher overall point prevalence rates from 0.2% (95% CI 0.9–79.4%; I2 = 98%) to 49% (95% CI 18–79.8%, I2 = 98%) for the term “medically unexplained symptoms” [142] compared to the here calculated results for FD. In specialized health-care systems, FD are even prevalent to higher degrees (from 29% [143] up to 66% [144]). Epidemiological findings differ in regard to the context (general population vs. primary/specialized care context) and the diagnosis (FD vs. specific FD diagnosis), the epidemiological aggregation of this study implicates that one out of ten adults in the general population suffer from FD, concluding that FD are highly prevalent across Europe. This also applies to the overall point prevalence rate of CP which resulted in 20.27% (95% CI from 16.51 to 24.63%). Worldwide, prevalence estimates show a wide range from 8.7 to 64.4% [13], and varies widely according to age of the sample, pain location or body region involved [14]. The overall point prevalence of IBS resulted in 9.08% (95% CI from 7.31 to 11.22%) across Europe, which is consistent with global estimates for IBS with 11.2% (95% CI 9.8–12.8%) [145]. Globally investigated prevalence on IBS varied depending on the country in which the research was conducted (lowest prevalence in Southeast Asia with 7.0% and highest in South America with 21.0%) and the diagnostic criteria applied (highest prevalence when 3 or more of the Manning criteria were used (14.0%; 95% CI 10.0–17.0%), the lowest was found when the Rome I criteria were used (8.8%; 95% CI 6.8–11.2%)) [145]. This serves as an example that prevalence rates become more homogeneous the more consensus exists regarding the custom taxonomy applied. Finally, the overall point prevalence of CWP was 8.45% (95% CI from 5.40 to 12.97%), similarly to CP there is a wide range of prevalence ranging from 1.4 to 24% [146].

There are several challenges in diagnosing FD even when clinicians follow one custom taxonomy, since few but impairing symptoms may not be captured, and also the utility of custom taxonomies in primary care is not yet proven evidentially (e.g., in BDS) [18]. To be noted that there is an overlap of functional somatic symptoms among multiple syndromes, such as CWP, IBS and CFS [3]. This may lead to difficulties in clearly distinguishing specific FD diagnoses, which may result in an overestimation in epidemiological investigations. To overcome diagnostic insecurities and imprecise clinical diagnosis, a new classification system for FD was proposed with regard to the body system in which those troublesome symptoms may occur (e.g., musculoskeletal, gastrointestinal, cardio-respiratory, genito-urinary, nervous system or fatigue related). This classification differs between one or more affected organ systems (so-called multi-system or single system) and a single persistent symptom (so-called single symptom) [147]. Psychological or behavioral dysfunctions may be present, but are not necessary for the diagnosis [147]. An occurrence with symptom-congruent medical conditions is possible and probable [147].

Some countries contributed a high number of studies (e.g., Sweden, UK), while others are missing (e.g., Austria, Belgium, Czech Republic, Hungary, Romania, Portugal, Lithuania). More Northern countries (e.g., Denmark, Norway, or Sweden) reported on prevalence taking the advantage of birth registers [148]. In addition, there are some European countries in which psychosomatic medicine is practiced [149] as an independent discipline, which entails having an institutional organization [150]. This may imply that some countries (e.g., Denmark, Germany, Great Britain, Netherlands, Norway, France, Italy, Spain, and Sweden) conduct more epidemiological studies than others, which may cause biases (over- or under-estimation) of the overall point prevalence estimation of FD and specific diagnoses across Europe. The highest overall prevalence rate was observed in Norway and the lowest in Denmark. Considering the prevalence estimates of specific diagnoses at the country level, significant differences were found. This suggests that there is a considerable degree of heterogeneity in the prevalence rates of FD across and within countries. This might echo alterations in methods applied to run the research and might be based on political, cultural, and health systems differences. Going more into details, the within countries difference can be related to the use of different diagnostic criteria (e.g., Rome I/II criteria or the modified Rome criteria according to Manning), to the use of clinical interviews in the assessment procedure, to the geographical location (rural vs urban settings)—might also play a role, and to the population characteristics, such as age, sex, socio-economic status. Additionally, differences in healthcare access and utilization patterns can play a role as well as the statistical methods used for data analysis, particularly in handling missing data. Heterogeneity might also origin from a different understanding of genesis and etiological mechanisms of FD, illness behaviors in differential cultural contexts, prevention approaches, and stigmatization. The health ministry of Denmark developed and implemented a mental health promotion package to regulate the management of mental illness [151], including digital psychiatry, early interventions, civil society initiatives, anti-stigmatization campaigns, suicide prevention [152]. National guidelines to treat FD in Denmark exist [153], which may elucidate an appropriate treatment for patients with FD and the low rate of FD. However, an improvement in the recognition, treatment, and anti-stigmatizing of FD is called for [154], such approaches to further improve care for patients with FD presents the awareness and relevance that FD have on the Danish country level. The Norwegian mental health systems show to be less efficient in treating patients with mental health problems [155] leading to longer periods of sick leave [156]. To the best of our knowledge, national guidelines for FD are lacking in Norway. Guidelines serve the aim to provide a set of structured recommendations for clinicians to confidently diagnose and treat patients to improve quality of care [157]. The World Health Organization’s guidelines in mental disorders [158], also adapted for the primary care setting [159], can support existing and future national and international guidelines developed by disorder-specific organizations.

Patient organizations or initiatives, as for example in the field of functional neurological disorders (e.g., FND Hope for functional neurological disorders [160]), are essential pioneers for the development of national and international guidelines. Unfortunately there are no current initiatives by European Parliament on FD, but they take stand on mental health not least due to the sequelae of the COVID-19 pandemic [161].

Finally, investments have a key role too. Denmark spends the most total costs (direct and indirect, measured by using the gross domestic direct product) in the sector of mental disorders in comparison to other EU countries, followed by Germany, Austria, and Spain [162], which might give another explanation for more engagement on the mental health sector to develop such national guidelines.

The present study has limitations. The PRISMA reporting guidelines [38] were followed to guarantee transparency and accuracy, but the results might not be free from biases. The inclusion of English published papers ensured the synthesis of high-quality studies but may have excluded some written in other languages. The inclusion of studies with a study population of ≥ 500 participants may be another limitation, since studies on smaller samples might use more accurate diagnostic procedures [163]. The Eggers’ test, Peters’ regression test, and the funnel plot indicated asymmetry, which may imply either publication biases or small-study effect, or both. Overall, even though tests of heterogeneity for each prevalence rate and subgroup demonstrated considerable variability, a precise statistical procedure was chosen with a-priori definitions of subgroups to reduce heterogeneity. Furthermore, the JBI revealed the majority of studies had a low risk of bias. However, studies with a low or moderate risk of bias were included in the analysis, which might lead to a bias of the actual results.

In conclusion, findings demonstrate a high prevalence, and thus impact, of FD in and on European populations [164]. Findings are in line with global estimations of the FD prevalence, however, comparability is problematic due to nosography and methodological challenges. Core outcomes are urgently needed to overcome heterogeneity in epidemiological studies on FD, in particular: a generally valid and recognized classification system and methodological assessment throughout Europe. For this, guidelines on national, but especially on international level, would be of immense importance and should straightaway be developed by leading European organizations and networks as a support across Europe.

These epidemiological data represent a basic principle of market research of supply and demand: the higher the demand due to FD patients, the higher the need of a functioning public health system with adequate care paths. Adequate health care should be provided under the light of the WHO practical suggestions of patient engagement [165], which highlights the relevance of patients’ active role within the decision-making process [166, 167] and brings patients’ transition from object to subjects in health care [168]. Results can also help to push healthcare policymakers acknowledging the relevance of FD and acting accordingly. This epidemiological estimations are essential to plan public health care efforts, scaling resources and needs for disease-modifying treatments and effective low-cost interventions [169].

References

Henningsen P, Gündel H, Kop WJ, Löwe B, Martin A, Rief W, Rosmalen JG, Schröder A, Van Der Feltz-Cornelis C, Van den Bergh O. Persistent physical symptoms as perceptual dysregulation: a neuropsychobehavioral model and its clinical implications. Psychosom Med. 2018;80:422–31.

Wessely S, Nimnuan C, Sharpe M. Functional somatic syndromes: one or many? The Lancet. 1999;354:936–9.

Creed F, Tomenson B, Chew-Graham C, Macfarlane G, Davies I, Jackson J, Littlewood A, McBeth J. Multiple somatic symptoms predict impaired health status in functional somatic syndromes. Int J Behav Med. 2013;20:194–205.

Tomenson B, Essau C, Jacobi F, Ladwig KH, Leiknes KA, Lieb R, Meinlschmidt G, McBeth J, Rosmalen J, Rief W. Total somatic symptom score as a predictor of health outcome in somatic symptom disorders. Br J Psychiatry. 2013;203:373–80.

Koloski NA, Talley NJ, Boyce PM. The impact of functional gastrointestinal disorders on quality of life. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:67–71.

Rask MT, Ørnbøl E, Rosendal M, Fink P. Long-term outcome of bodily distress syndrome in primary care: a follow-up study on health care costs, work disability, and self-rated health. Psychosom Med. 2017;79:345.

Burton C, McGorm K, Richardson G, Weller D, Sharpe M. Healthcare costs incurred by patients repeatedly referred to secondary medical care with medically unexplained symptoms: a cost of illness study. J Psychosom Res. 2012;72:242–7.

Hyler SE, Sussman N. Somatoform disorders: before and after DSM-III. Psychiatr Serv. 1984;35:469–78.

Yunus MB: Fibromyalgia and overlapping disorders: the unifying concept of central sensitivity syndromes. In: Seminars in arthritis and rheumatism. Elsevier; 2007. pp. 339–356.

Encompassing Training in fUnctional Disorders across Europe (ETUDE) https://www.euronet-soma.eu/itn/etude/

Sarmiento C, Lau C. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM‐5. In: The wiley encyclopedia of personality and individual differences: personality processes and individual differences; 2020. pp. 125–129.

Research APADo. Highlights of changes from dsm-iv to dsm-5: somatic symptom and related disorders. Focus. 2013;11:525–7.

Organization WH: International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems: alphabetical index. World Health Organization; 2004.

Gureje O. Classification of somatic syndromes in ICD-11. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2015;28:345–9.

Gureje O, Reed GM. Bodily distress disorder in ICD-11: problems and prospects. World Psychiatry. 2016;15:291.

Fava GA, Freyberger HJ, Bech P, Christodoulou G, Sensky T, Theorell T, Wise TN. Diagnostic criteria for use in psychosomatic research. Psychother Psychosom. 1995. https://doi.org/10.1159/000288931.

Porcelli P, Guidi J. The clinical utility of the diagnostic criteria for psychosomatic research: a review of studies. Psychother Psychosom. 2015;84:265–72.

Budtz-Lilly A, Schröder A, Rask MT, Fink P, Vestergaard M, Rosendal M. Bodily distress syndrome: a new diagnosis for functional disorders in primary care? BMC Fam Pract. 2015;16:1–10.

Münker L, Rimvall MK, Frostholm L, Ørnbøl E, Wellnitz KB, Rosmalen J, Rask CU. Can the bodily distress syndrome (BDS) concept be used to assess functional somatic symptoms in adolescence? J Psychosom Res. 2022;163:111064.

Lacy BE, Patel NK. Rome criteria and a diagnostic approach to irritable bowel syndrome. J Clin Med. 2017;6:99.

Porcelli P, De Carne M, Leandro G. Distinct associations of DSM-5 somatic symptom disorder, the diagnostic criteria for psychosomatic research-revised (DCPR-R) and symptom severity in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2020;64:56–62.

Nicholas M, Vlaeyen JW, Rief W, Barke A, Aziz Q, Benoliel R, Cohen M, Evers S, Giamberardino MA, Goebel A. The IASP classification of chronic pain for ICD-11: chronic primary pain. Pain. 2019;160:28–37.

Manning A, Thompson W, Heaton K, Morris A. Towards positive diagnosis of the irritable bowel. Br Med J. 1978;2:653–4.

Agréus L, Talley N, Svärdsudd K, Tibblin G, Jones M. Identifying dyspepsia and irritable bowel syndrome: the value of pain or discomfort, and bowel habit descriptors. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2000;35:142–51.

Saito YA, Locke GR III, Talley NJ, Zinsmeister AR, Fett SL, Melton LJ III. A comparison of the Rome and manning criteria for case identification in epidemiological investigations of irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:2816–24.

Dang J, Ardila-Hani A, Amichai MM, Chua K, Pimentel M. Systematic review of diagnostic criteria for IBS demonstrates poor validity and utilization of Rome III. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2012;24:853-e397.

Radovanovic-Dinic B, Tesic-Rajkovic S, Grgov S, Petrovic G, Zivkovic V. Irritable bowel syndrome-from etiopathogenesis to therapy. Biomed Pap Med Fac Palacky Univ Olomouc. 2018. https://doi.org/10.5507/bp.2017.057.

Wolfe F, Smythe HA, Yunus MB, Bennett RM, Bombardier C, Goldenberg DL, Tugwell P, Campbell SM, Abeles M, Clark P. The American college of rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of fibromyalgia. Arthr Rheum: Off J Am Coll Rheumatol. 1990;33:160–72.

Wolfe F, Clauw DJ, Fitzcharles MA, Goldenberg DL, Katz RS, Mease P, Russell AS, Russell IJ, Winfield JB, Yunus MB. The American college of rheumatology preliminary diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia and measurement of symptom severity. Arthritis Care Res. 2010;62:600–10.

Petersen MW, Schröder A, Jørgensen T, Ørnbøl E, Meinertz Dantoft T, Eliasen M, Benros ME, Fink P. Irritable bowel, chronic widespread pain, chronic fatigue and related syndromes are prevalent and highly overlapping in the general population: DanFunD. Sci Rep. 2020;10:1–10.

Kim S, Chang L. Overlap between functional GI disorders and other functional syndromes: what are the underlying mechanisms? Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2012;24:895–913.

What is Prevalence? https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/what-is-prevalence#:~:text=Period%20prevalence%20is%20the%20proportion,has%20ever%20had%20the%20characteristic.

Naing L, Winn T, Rusli B. Practical issues in calculating the sample size for prevalence studies. Arch Orofac Sci. 2006;1:9–14.

Arya R, Antonisamy B, Kumar S. Sample size estimation in prevalence studies. Indian J Pediatr. 2012;79:1482–8.

Schwarzer G, Chemaitelly H, Abu-Raddad LJ, Rücker G. Seriously misleading results using inverse of Freeman–Tukey double arcsine transformation in meta-analysis of single proportions. Res synth Methods. 2019;10:476–83.

Harrer M, Cuijpers P, Furukawa TA, Ebert DD. Doing meta-analysis with R: a hands-on guide. Chapman and Hall/CRC; 2021.

Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan: a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016;5:1–10.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int J Surg. 2021;88:105906.

Hupe M. EndNote X9. J Electron Resour Med Lib. 2019;16:117–9.

Caroline Rometsch GM, Sara Romanazzo, Alexandra Martin, Fiammetta Cosci: Transdiagnostic prevalence of functional disorders across Europe: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. PROSPERO 2021:CRD42022298974.

Institute JB. JBI critical appraisal checklist for studies reporting prevalence data. Adelaide: University of Adelaide; 2017.

Munn Z, Moola S, Lisy K, Riitano D, Tufanaru C. Methodological guidance for systematic reviews of observational epidemiological studies reporting prevalence and cumulative incidence data. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13:147–53.

Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33(1):159–74.

Lin L, Chu H. Meta-analysis of proportions using generalized linear mixed models. Epidemiology. 2020;31:713.

Viechtbauer W. Bias and efficiency of meta-analytic variance estimators in the random-effects model. J Educ Behav Stat. 2005;30:261–93.

Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21:1539–58.

Rosmalen J, Burton C, Carson A, Cosci F, Frostholm L, Lehnen N, Hartman TO. The European training network ETUDE (encompassing training in functional disorders across Europe) is recruiting 15 early-stage researchers. Psychother Psychosom. 2021;90:142–4.

Nacul LC, Lacerda EM, Pheby D, Campion P, Molokhia M, Fayyaz S, Leite JC, Poland F, Howe A, Drachler ML. Prevalence of myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) in three regions of England: a repeated cross-sectional study in primary care. BMC Med. 2011;9:1–12.

Corazziari E, Attili A, Angeletti C, De Santis A. Biliary colic is highly prevalent, but is not the main indication for cholecystectomy, in IBS subjects with gallstones. MICOL population-based study. In: Gastroenterology. WB saunders co independence square west Curtis center, STE 300, PHILADELPHIA; 2004. pp. A367–A368.

Constantinidis TS, Arvaniti C, Fakas N, Rudolf J, Kouremenos E, Giannouli E, Mitsikostas DD. A population-based survey for disabling headaches in Greece: prevalence, burden and treatment preferences. Cephalalgia. 2021;41:810–20.

Göbel H, Petersen-Braun M, Soyka D. The epidemiology of headache in Germany: a nationwide survey of a representative sample on the basis of the headache classification of the international headache society. Cephalalgia. 1994;14:97–106.

Kristiansen HA, Kværner KJ, Akre H, Øverland B, Russell MB. Tension-type headache and sleep apnea in the general population. J Headache Pain. 2011;12:63–9.

Ottar Sjaastad M, Bakketeig LS. Tension-type headache. Comparison with migraine without aura and cervicogenic headache. The Vågå study of headache epidemiology. Funct Neurol. 2008;23:71.

Garcia-Campayo J, Lobo A, Perez-Echeverria MJ, Campos R. Three forms of somatization presenting in primary care settings in Spain. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1998;186:554–60.

Grabe HJ, Meyer C, Hapke U, Rumpf H-J, Freyberger HJ, Dilling H, John U. Specific somatoform disorder in the general population. Psychosomatics. 2003;44:304–11.

De Waal MWM, Arnold IA, Eekhof JA, Van Hemert AM. Somatoform disorders in general practice: prevalence, functional impairment and comorbidity with anxiety and depressive disorders. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;184:470–6.

Norton J, De Roquefeuil G, Boulenger J-P, Ritchie K, Mann A, Tylee A. Use of the PRIME-MD patient health questionnaire for estimating the prevalence of psychiatric disorders in French primary care: comparison with family practitioner estimates and relationship to psychotropic medication use. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2007;29:285–93.

Hanel G, Henningsen P, Herzog W, Sauer N, Schaefert R, Szecsenyi J, Löwe B. Depression, anxiety, and somatoform disorders: vague or distinct categories in primary care? Results from a large cross-sectional study. J Psychosom Res. 2009;67:189–97.

Roca M, Gili M, Garcia-Garcia M, Salva J, Vives M, Campayo JG, Comas A. Prevalence and comorbidity of common mental disorders in primary care. J Affect Disord. 2009;119:52–8.

Haftgoli N, Favrat B, Verdon F, Vaucher P, Bischoff T, Burnand B, Herzig L. Patients presenting with somatic complaints in general practice: depression, anxiety and somatoform disorders are frequent and associated with psychosocial stressors. BMC Fam Pract. 2010;11:1–8.

Schaefert R, Laux G, Kaufmann C, Schellberg D, Bölter R, Szecsenyi J, Sauer N, Herzog W, Kuehlein T. Diagnosing somatisation disorder (P75) in routine general practice using the international classification of primary care. J Psychosom Res. 2010;69:267–77.

Toft T, Fink P, Oernboel E, Christensen K, Frostholm L, Olesen F. Mental disorders in primary care: prevalence and co-morbidity among disorders. Results from the functional illness in primary care (FIP) study. Psychol Med. 2005;35:1175–84.

Lobo A, García-Campayo J, Campos R, Marcos G, Pérez-Echeverria MJ. Somatisation in primary care in Spain: I. Estimates of prevalence and clinical characteristics. Br J Psychiatry. 1996;168:344–8.

Líndal E, Stefánsson JG, Bergmann S. The prevalence of chronic fatigue syndrome in Iceland-a national comparison by gender drawing on four different criteria. Nord J Psychiatry. 2002;56:273–7.

Harvey SB, Wadsworth M, Wessely S, Hotopf M. Etiology of chronic fatigue syndrome: testing popular hypotheses using a national birth cohort study. Psychosom Med. 2008;70:488–95.

Kato K, Sullivan PF, Evengård B, Pedersen NL. A population-based twin study of functional somatic syndromes. Psychol Med. 2009;39:497–505.

van’t Leven M, Zielhuis GA, van der Meer JW, Verbeek AL, Bleijenberg G. Fatigue and chronic fatigue syndrome-like complaints in the general population. Eur J Pub Health. 2010;20:251–7.

Janssens KA, Zijlema WL, Joustra ML, Rosmalen JG. Mood and anxiety disorders in chronic fatigue syndrome, fibromyalgia, and irritable bowel syndrome: results from the LifeLines cohort study. Psychosom Med. 2015;77:449–57.

Petersen MW, Schröder A, Jørgensen T, Ørnbøl E, Dantoft TM, Eliasen M, Carstensen TW, Falgaard Eplov L, Fink P. Prevalence of functional somatic syndromes and bodily distress syndrome in the Danish population: the DanFunD study. Scand J Pub Health. 2020;48:567–76.

Mäkelä M, Heliövaara M. Prevalence of primary fibromyalgia in the Finnish population. BMJ. 1991;303:216–9.

Forseth K, Gran J. The prevalence of fibromyalgia among women aged 20–49 years in Arendal. Noway Scand J Rheumatol. 1992;21:74–8.

Prescott E, Kjøller M, Jacobsen S, Bülow P, Danneskiold-Samsøe B, Kamper-Jørgensen F. Fibromyalgia in the adult Danish population: I. a prevalence study. Scand J Rheumatol. 1993;22:233–7.

Lindell L, Bergman S, Petersson IF, Jacobsson LT, Herrström P. Prevalence of fibromyalgia and chronic widespread pain. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2000;18:149–53.

Carmona L, Ballina J, Gabriel R, Laffon A. The burden of musculoskeletal diseases in the general population of Spain: results from a national survey. Ann Rheum Dis. 2001;60:1040–5.

Schochat T, Raspe H. Elements of fibromyalgia in an open population. Rheumatology. 2003;42:829–35.

Salaffi F, De Angelis R, Grassi W. Prevalence of musculoskeletal conditions in an Italian population sample: results of a regional community-based study. I. The MAPPING study. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2005;23:819–28.

Mas A, Carmona L, Valverde M, Ribas B. Prevalence and impact of fibromyalgia on function and quality of life in individuals from the general population: results from a nationwide study in Spain. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2008;26:519.

Perrot S, Vicaut E, Servant D, Ravaud P. Prevalence of fibromyalgia in France: a multi-step study research combining national screening and clinical confirmation: the DEFI study (determination of epidemiology of fibromyalgia). BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2011;12:1–9.

Lourenço S, Costa L, Rodrigues AM, Carnide F, Lucas R. Gender and psychosocial context as determinants of fibromyalgia symptoms (fibromyalgia research criteria) in young adults from the general population. Rheumatology. 2015;54:1806–15.

Gayà TF, Ferrer CB, Mas AJ, Seoane-Mato D, Reyes FÁ, Sánchez MD, Dubois CM, Sánchez-Fernández SA, Vargas LMR, Morales PG. Prevalence of fibromyalgia and associated factors in Spain. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2020;123:47–52.

Jones GT, Atzeni F, Beasley M, Flüß E, Sarzi-Puttini P, Macfarlane GJ. The prevalence of fibromyalgia in the general population: a comparison of the American college of rheumatology 1990, 2010, and modified 2010 classification criteria. Arthrit Rheumatol. 2015;67:568–75.

Croft P, Rigby A, Boswell R, Schollum J, Silman A. The prevalence of chronic widespread pain in the general population. J Rheumatol. 1993;20:710–3.

Hunt I, Silman A, Benjamin S, McBeth J, Macfarlane G. The prevalence and associated features of chronic widespread pain in the community using the’Manchester’definition of chronic widespread pain. Rheumatology (Oxford). 1999;38:275–9.

Bergman S, Herrström P, Jacobsson LT, Petersson IF. Chronic widespread pain: a three year followup of pain distribution and risk factors. J Rheumatol. 2002;29:818–25.

Aggarwal VR, McBeth J, Zakrzewska JM, Lunt M, Macfarlane GJ. The epidemiology of chronic syndromes that are frequently unexplained: do they have common associated factors? Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35:468–76.

Carnes D, Parsons S, Ashby D, Breen A, Foster N, Pincus T, Vogel S, Underwood M: Chronic musculoskeletal pain rarely presents in a single body site: results from a UK population study; 2007.

Gerdle B, Björk J, Cöster L, Henriksson K-G, Henriksson C, Bengtsson A. Prevalence of widespread pain and associations with work status: a population study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2008;9:1–10.

VanDenKerkhof EG, Macdonald HM, Jones GT, Power C, Macfarlane GJ. Diet, lifestyle and chronic widespread pain: results from the 1958 British Birth cohort study. Pain Res Manage. 2011;16:87–92.

Gale CR, Deary IJ, Cooper C, Batty GD. Intelligence in childhood and chronic widespread pain in middle age: the national child development survey. PAIN®. 2012;153:2339–44.

Choudhury Y, Bremner SA, Ali A, Eldridge S, Griffiths CJ, Hussain I, Parsons S, Rahman A, Underwood M. Prevalence and impact of chronic widespread pain in the Bangladeshi and White populations of Tower Hamlets. East London Clin Rheumatol. 2013;32:1375–82.

Gerhardt A, Hartmann M, Blumenstiel K, Tesarz J, Eich W. The prevalence rate and the role of the spatial extent of pain in nonspecific chronic back pain: a population-based study in the south-west of Germany. Pain Med. 2014;15:1200–10.

Mundal I, Gråwe RW, Bjørngaard JH, Linaker OM, Fors EA. Prevalence and long-term predictors of persistent chronic widespread pain in the general population in an 11-year prospective study: the HUNT study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2014;15:1–12.

Burri A, Ogata S, Vehof J, Williams F. Chronic widespread pain: clinical comorbidities and psychological correlates. Pain. 2015;156:1458–64.

Flüß E, Bond CM, Jones GT, Macfarlane GJ. The re-evaluation of the measurement of pain in population-based epidemiological studies: the SHAMA study. Br J Pain. 2015;9:134–41.

Walker-Bone K, Harvey NC, Ntani G, Tinati T, Jones GT, Smith BH, Macfarlane GJ, Cooper C. Chronic widespread bodily pain is increased among individuals with history of fracture: findings from UK Biobank. Arch Osteoporos. 2016;11:1–10.

Bergmann MM, Jacobs EJ, Hoffmann K, Boeing H. Agreement of self-reported medical history: comparison of an in-person interview with a self-administered questionnaire. Eur J Epidemiol. 2004;19:411–6.

Bommelaer G, Poynard T, Le Pen C, Gaudin A-F, Maurel F, Priol G, Amouretti M, Frexinos J, Ruszniewski P, El Hasnaoui A. Prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and variability of diagnostic criteria. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2004;28:554–61.

Mearin XB, Balboa A, Baró E, Caldwell E, Cucala M, Díaz-Rubio M, Fueyo A, Ponce J, Roset M, Talley NJ. Irritable bowel syndrome prevalence varies enormously depending on the employed diagnostic criteria: comparison of Rome II versus previous criteria in a general population. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2001;36:1155–61.

Österberg E, Blomquist L, Krakau I, Weinryb R, Åsberg M, Hultcrantz R. A population study on irritable bowel syndrome and mental health. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2000;35:264–8.

Badia X, Mearin F, Balboa A, Baró E, Caldwell E, Cucala M, Díaz-Rubio M, Fueyo A, Ponce J, Roset M. Burden of illness in irritable bowel syndrome comparing Rome I and Rome II criteria. Pharmacoeconomics. 2002;20:749–58.

Bommelaer G, Dorval E, Denis P, Czernichow P, Frexinos J, Pelc A, Slama A, El Hasnaoui A. Prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome in the French population according to the Rome I criteria. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2002;26:1118–23.

Baretić M, Bilić A, Jurcić D, Mihanović M, Sunić-Omejc M, Dorosulić Z, Restek-Petrović B. Epidemiology of irritable bowel syndrome in Croatia. Coll Antropol. 2002;26:85–91.

Hillilä M, Färkkilä M. Prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome according to different diagnostic criteria in a non-selected adult population. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:339–45.

Sperber AD, Bangdiwala SI, Drossman DA, Ghoshal UC, Simren M, Tack J, Whitehead WE, Dumitrascu DL, Fang X, Fukudo S. Worldwide prevalence and burden of functional gastrointestinal disorders, results of Rome Foundation global study. Gastroenterology. 2021;160(99–114):e113.

Heaton KW, O’Donnell LJ, Braddon FE, Mountford RA, Hughes AO, Cripps PJ. Symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome in a British urban community: consulters and nonconsulters. Gastroenterology. 1992;102:1962–7.

Boekema PJ, van Isselt EFVD, Bots ML, Smout AJ. Functional bowel symptoms in a general Dutch population and associations with common stimulants. Neth J Med. 2001;59:23–30.

Ziółkowski BA, Pacholec A, Kudlicka M, Ehrmann A, Muszyński J. Prevalence of abdominal symptoms in the Polish population. Gastroenterol Rev/Przegląd Gastroenterol. 2012;7:20–5.

Van den Houte K, Carbone F, Pannemans J, Corsetti M, Fischler B, Piessevaux H, Tack J. Prevalence and impact of self-reported irritable bowel symptoms in the general population. United Eur Gastroenterol J. 2019;7:307–15.

Brattberg G, Thorslund M, Wikman A. The prevalence of pain in a general population. The results of a postal survey in a county of Sweden. Pain. 1989;37:215–22.

Chrubasik S, Junck H, Zappe H, Stutzke O. A survey on pain complaints and health care utilization in a German population sample. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 1998;15:397–408.

Catala E, Reig E, Artes M, Aliaga L, López J, Segu J. Prevalence of pain in the Spanish population: telephone survey in 5000 homes. Eur J Pain. 2002;6:133–40.

Rustøen T, Wahl AK, Hanestad BR, Lerdal A, Paul S, Miaskowski C. Prevalence and characteristics of chronic pain in the general Norwegian population. Eur J Pain. 2004;8:555–65.

Breivik H, Collett B, Ventafridda V, Cohen R, Gallacher D. Survey of chronic pain in Europe: prevalence, impact on daily life, and treatment. Eur J Pain. 2006;10:287–333.

Jablonska B, Soares JJ, Sundin Ö. Pain among women: associations with socio-economic and work conditions. Eur J Pain. 2006;10:435–47.

Bouhassira D, Lantéri-Minet M, Attal N, Laurent B, Touboul C. Prevalence of chronic pain with neuropathic characteristics in the general population. Pain. 2008;136:380–7.

Landmark T, Romundstad P, Dale O, Borchgrevink PC, Kaasa S. Estimating the prevalence of chronic pain: validation of recall against longitudinal reporting (the HUNT pain study). Pain. 2012;153:1368–73.

Azevedo LF, Costa-Pereira A, Mendonça L, Dias CC, Castro-Lopes JM. Epidemiology of chronic pain: a population-based nationwide study on its prevalence, characteristics and associated disability in Portugal. J Pain. 2012;13:773–83.

Björnsdóttir S, Jónsson S, Valdimarsdóttir U. Functional limitations and physical symptoms of individuals with chronic pain. Scand J Rheumatol. 2013;42:59–70.

Dueñas M, Salazar A, Ojeda B, Fernández-Palacín F, Micó JA, Torres LM, Failde I. A nationwide study of chronic pain prevalence in the general Spanish population: identifying clinical subgroups through cluster analysis. Pain Med. 2015;16:811–22.

Del Giorno R, Frumento P, Varrassi G, Paladini A, Coaccioli S. Assessment of chronic pain and access to pain therapy: a cross-sectional population-based study. J Pain Res. 2017;10:2577.

Gouveia N, Rodrigues A, Eusébio M, Ramiro S, Machado P, Canhao H, Branco JC. Prevalence and social burden of active chronic low back pain in the adult Portuguese population: results from a national survey. Rheumatol Int. 2016;36:183–97.

Hillman M, Wright A, Rajaratnam G, Tennant A, Chamberlain M. Prevalence of low back pain in the community: implications for service provision in Bradford, UK. J Epidemiol Commun Health. 1996;50:347–52.

Heuch I, Hagen K, Heuch I, Nygaard Ø, Zwart J-A. The impact of body mass index on the prevalence of low back pain: the HUNT study. Spine. 2010;35:764–8.

Ho KKN, Simic M, Småstuen MC, de Barros PM, Ferreira PH, Johnsen MB, Heuch I, Grotle M, Zwart JA, Nilsen KB. The association between insomnia, c-reactive protein, and chronic low back pain: Cross-sectional analysis of the HUNT study. Norway Scand J Pain. 2019;19:765–77.

Smith BH, Elliott AM, Hannaford PC, Chambers WA, Smith WC. Factors related to the onset and persistence of chronic back pain in the community: results from a general population follow-up study. Spine. 2004;29:1032–40.

Bjorck-Van Dijken C, Fjellman-Wiklund A, Hildingsson C. Low back pain, lifestyle factors and physical activity: a population based-study. J Rehabil Med. 2008;40:864.

Wijnhoven HA, De Vet HC, Picavet HSJ. Prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders is systematically higher in women than in men. Clin J Pain. 2006;22:717–24.

Hagen K, Linde M, Heuch I, Stovner LJ, Zwart J-A. Increasing prevalence of chronic musculoskeletal complaints. A large 11-year follow-up in the general population (HUNT 2 and 3). Pain Med. 2011;12:1657–66.

Macfarlane GJ, Beasley M, Smith BH, Jones GT, Macfarlane TV. Can large surveys conducted on highly selected populations provide valid information on the epidemiology of common health conditions? An analysis of UK Biobank data on musculoskeletal pain. Br J Pain. 2015;9:203–12.

Bergman S, Herrström P, Högström K, Petersson IF, Svensson B, Jacobsson LT. Chronic musculoskeletal pain, prevalence rates, and sociodemographic associations in a Swedish population study. J Rheumatol. 2001;28:1369–77.

Margueritte F, Fritel X, Zins M, Goldberg M, Panjo H, Fauconnier A, Ringa V. The underestimated prevalence of neglected chronic pelvic pain in women, a nationwide cross-sectional study in France. J Clin Med. 2021;10:2481.

Zondervan KT, Yudkin PL, Vessey MP, Jenkinson CP, Dawes MG, Barlow DH, Kennedy SH. Chronic pelvic pain in the community: symptoms, investigations, and diagnoses. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184:1149–55.

Mohedo ED, Wärnberg J, López FB, Velasco SM, Burgos AC. Chronic pelvic pain in Spanish women: prevalence and associated risk factors. A crosssectional study. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2014;41:243–8.

Mäkela M, Heliövaara M, Sievers K, Impivaara O, Knekt P, Aromaa A. Prevalence, determinants, and consequences of chronic neck pain in Finland. Am J Epidemiol. 1991;134:1356–67.

Guez M, Hildingsson C, Stegmayr B, Toolanen G. Chronic neck pain of traumatic and non-traumatic origin A population-based study. Acta Orthop Scand. 2003;74:576–9.

Guez M, Hildingsson C, Nilsson M, Toolanen G. The prevalence of neck pain. Acta Orthop Scand. 2002;73:455–9.

Wertli MM, Dangma TD, Müller SE, Gort LM, Klauser BS, Melzer L, Held U, Steurer J, Hasler S, Burgstaller JM. Non-cardiac chest pain patients in the emergency department: Do physicians have a plan how to diagnose and treat them? A retrospective study. PLoS ONE. 2019;14:e0211615.

Icks A, Haastert B, Enck P, Rathmann W, Giani G. Prevalence of functional bowel disorders and related health care seeking: a population-based study. Z Gastroenterol. 2002;40:177–83.

Sperber AD, Shvartzman P, Friger M, Fich A. A comparative reappraisal of the Rome II and Rome III diagnostic criteria: are we getting closer to the ‘true’prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome? Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;19:441–7.

Petersen MW, Ørnbøl E, Dantoft TM, Fink P. Assessment of functional somatic disorders in epidemiological research: Self-report questionnaires versus diagnostic interviews. J Psychosom Res. 2021;146:110491.

Löwe B, Levenson J, Depping M, Hüsing P, Kohlmann S, Lehmann M, Shedden-Mora M, Toussaint A, Uhlenbusch N, Weigel A. Somatic symptom disorder: a scoping review on the empirical evidence of a new diagnosis. Psychol Med. 2022;52:632–48.

Haller H, Cramer H, Lauche R, Dobos G. Somatoform disorders and medically unexplained symptoms in primary care: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2015;112:279.

Maiden N, Hurst N, Lochhead A, Carson A, Sharpe M. Medically unexplained symptoms in patients referred to a specialist rheumatology service: prevalence and associations. Rheumatology. 2003;42:108–12.

Nimnuan C, Hotopf M, Wessely S. Medically unexplained symptoms: an epidemiological study in seven specialities. J Psychosom Res. 2001;51:361–7.

Lovell RM, Ford AC. Global prevalence of and risk factors for irritable bowel syndrome: a meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10(712–721):e714.

Andrews P, Steultjens M, Riskowski J. Chronic widespread pain prevalence in the general population: a systematic review. Eur J Pain 2018;22(1):5–18.

Burton C, Fink P, Henningsen P, Löwe B, Rief W. Functional somatic disorders: discussion paper for a new common classification for research and clinical use. BMC Med. 2020;18:1–7.

Bliddal M, Broe A, Pottegård A, Olsen J, Langhoff-Roos J. The Danish medical birth register. Eur J Epidemiol. 2018;33:27–36.

Leigh H. Global psychosomatic medicine and consultation-liaison psychiatry: theory, research, education, and practice. Springer; 2019.

Deter H-C, Kruse J, Zipfel S. History, aims and present structure of psychosomatic medicine in Germany. BioPsychoSocial Med. 2018;12:1–10.

Health care in Denmark an overview https://www.healthcaredenmark.dk/media/ykedbhsl/healthcare-dk.pdf

The Danish Approach to Mental Health https://www.healthcaredenmark.dk/media/vbhmxkzk/triple-3i_mental-health_brochure_a5_low.pdf

Creed F, Fink P, Henningsen P: New Danish and German guidelines for “Bodily distress” and functional disorders published.

Brostrøm S. Improving care for patients with functional disorders in Denmark. J Psychosom Res. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2018.11.003.

Sperre Saunes I, Karanikolos M, Sagan A, Organization WH: Norway: health system review. 2020.

OECD: Norwegens Sozialsystem für psychisch Kranke eine Falle https://www.aerzteblatt.de/nachrichten/53647/OECD-Norwegens-Sozialsystem-fuer-psychisch-Kranke-eine-Falle

Woolf SH, Grol R, Hutchinson A, Eccles M, Grimshaw J. Potential benefits, limitations, and harms of clinical guidelines. BMJ. 1999;318:527–30.

Organization WH: Management of physical health conditions in adults with severe mental disorders: WHO guidelines. 2018.

Organization WH: Diagnostic and management guidelines for mental disorders in primary care: ICD-10. Chapter 5, Primary care version. World Health Organization; 1996.

Stone J, Burton C, Carson A. Recognising and explaining functional neurological disorder. BMJ. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m3745.

Mental health and the pandemic https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2021/696164/EPRS_BRI(2021)696164_EN.pdf

Mental health problems costing Europe heavily https://www.oecd.org/health/mental-health-problems-costing-europe-heavily.htm

Egger M, Buitrago-Garcia D, Smith GD. Systematic reviews of epidemiological studies of etiology and prevalence. Syst Rev Health Res: Meta-Anal Context. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119099369.ch19.

Collaborators GMD. Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Psychiatry. 2022;9:137–50.

Organization WH. Patient engagement; 2016.

Valderas Martinez J, Ricci-Cabello N, Prasopa-Plazier N, Wensing M, Santana M, Kaitiritimba R, Vazquez Curiel E, Murphy M. Patient engagement: WHO technical series on safer primary care. World Health Organisation; 2016.

Hart JT. Clinical and economic consequences of patients as producers. J Public Health. 1995;17:383–6.

Bishop S, Waring J. From boundary object to boundary subject; the role of the patient in coordination across complex systems of care during hospital discharge. Soc Sci Med. 2019;235:112370.

Nichols E, Steinmetz JD, Vollset SE, Fukutaki K, Chalek J, Abd-Allah F, Abdoli A, Abualhasan A, Abu-Gharbieh E, Akram TT. Estimation of the global prevalence of dementia in 2019 and forecasted prevalence in 2050: an analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Public Health. 2022;7:e105–25.

Acknowledgements

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska Curie grant agreement No 956673.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Firenze within the CRUI-CARE Agreement. This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No 956673. This article reflects only the author's view, the Agency is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information it contains.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by CR and FC with the support of GM, FMGB and AM. The first draft of the manuscript was written by CR and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethics approval

This is a systematic review and meta-analysis. No ethical approval is required.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rometsch, C., Mansueto, G., Maas Genannt Bermpohl, F. et al. Prevalence of functional disorders across Europe: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Epidemiol (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-024-01109-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-024-01109-5