Abstract

Dispositional optimism is a potentially modifiable factor and has been associated with multiple physical health outcomes, but its relationship with depression, especially later in life, remains unclear. In the Nurses´ Health Study (n = 33,483), we examined associations between dispositional optimism and depression risk in women aged 57–85 (mean = 69.9, SD = 6.8), with 4,051 cases of incident depression and 10 years of follow-up (2004–2014). We defined depression as either having a physician/clinician-diagnosed depression, or regularly using antidepressants, or the presence of severe depressive symptoms using validated self-reported scales. Age- and multivariable-adjusted Cox proportional hazards models were used to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) across optimism quartiles and for a 1-standard deviation (SD) increment of the optimism score. In sensitivity analyses we explored more restrictive definitions of depression, potential mediators, and moderators. In multivariable-adjusted models, women with greater optimism (top vs. bottom quartile) had a 27% (95%CI = 19–34%) lower risk of depression. Every 1-SD increase in the optimism score was associated with a 15% (95%CI = 12–18%) lower depression risk. When applying a more restrictive definition for clinical depression, the association was considerably attenuated (every 1-SD increase in the optimism score was associated with a 6% (95%CI = 2–10%-) lower depression risk. Stratified analyses by baseline depressive symptoms, age, race, and birth region revealed comparable estimates, while mediators (emotional support, social network size, healthy lifestyle), when combined, explained approximately 10% of the optimism-depression association. As social and behavioral factors only explained a small proportion of the association, future research should investigate other potential pathways, such as coping strategies, that may relate optimism to depression risk.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

One in five individuals experience at least one major depressive episode in their lifetime. Of these, 80% have another episode, and 25% develop chronic symptoms (≥ 2 years) [1], often remaining undetected and untreated [2]. Because of its high societal burden, lifelong nature, difficulties in detection and treatment, and association with adverse health outcomes (e.g., cardiovascular disease [3, 4]), prevention should be given top priority [5].

Individuals with higher dispositional optimism—i.e., high expectations for positive outcomes in the future and low expectations for negative events [6]—experience significantly lower risk of depression and related outcomes [7,8,9,10], partially explained by better coping [11, 12], receiving more social support [13, 14] and a healthier lifestyle [15]. Optimism is strongly related to four of the Big Five factors of personality, with neuroticism and extraversion explaining by far the largest proportion of variance in optimism compared to agreeableness and conscientiousness [16]. Optimism can be enhanced via training [17]; thus, it is a modifiable factor that may help to prevent depression.

Despite a large body of literature on the association of dispositional optimism and depression-related outcomes, evidence from longitudinal studies with detailed confounder adjustment remains scarce. To date, four prospective studies have assessed the association between dispositional optimism and incident depression [7,8,9,10]. Three were based on the same adult population (mean age 44 years) of the Finnish Public Sector Study, showing high optimism to be associated with significantly lower risk of depressive disorder [8], work disability due to depression [9], and starting antidepressant medication treatment [7]. Among 464 elderly men (mean age 70.8 years), high vs. low optimism predicted a lower cumulative incidence of depressive symptoms over 15 years of follow-up, after detailed control for confounding [10]. To date, no study has examined this association among women of comparable age, who are generally more likely to experience depression [18, 19].

We examined in a large prospective cohort of middle-aged and older US women whether dispositional optimism predicted risk of incident depression in later life. We investigated effect modification by race, region of birth [20], age and baseline depressive symptoms and evaluated mediation by behavioral and social factors [21]. To minimize bias through the inclusion of potentially misclassified depression cases we conducted sensitivity analyses restricting the depression definition to physician diagnosed cases with anti-depressant use. Nonetheless, given the high validity of many of the outcomes including depression in the Nurses’ Health Study cohorts, we did not expect that applying a more stringent definition of depression would substantially alter our results.

Methods

Study population

The Nurses’ Health Study (NHS) began in 1976 when 121,700 U.S. female nurses aged 30–55 years returned a mailed questionnaire regarding socio-demographics, lifestyle, and medical history. Biennial follow-up questionnaires queried information on psychosocial factors, including depression and optimism, as well as incident medical conditions. Voluntary return of the questionnaires implies informed consent; the study protocol was approved by the institutional review boards of the Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, and those of participating registries as required.

Dispositional optimism

Dispositional optimism was assessed in 2004, 2008, and 2012 using the Life Orientation Test-Revised (LOT-R), the most commonly used, validated self-reported questionnaire to assess optimism. Six statements are rated with responses on a 5-point Likert Scale (0–4) rendering a scale from 0 to 24, with higher scores indicating higher optimism [22]. Quartiles were calculated to reduce the impact of influential outliers and to be able to distinguish effects, for example, between the least optimistic (Q1) vs. most optimistic (Q4) and least optimistic (Q1) vs. less optimistic (Q2) rather than merely looking at a one unit or a one SD increase in the optimism score. Overall stability across the three assessments of optimism was good (ICC = 0.59). Cronbach´s alpha for the assessment at baseline was 0.71.

Depression

Depression was defined as clinician-diagnosed depression, regular antidepressant use, or the presence of severe depressive symptoms, as used in previous studies [18, 20, 21]. In sensitivity analyses, to minimize potential misclassification bias, two more restrictive definitions of depression were applied, 1. More restrictive: clinician-diagnosed depression or antidepressants use; 2. Most restrictive: clinician-diagnosed depression and antidepressants use [23].

Self-reported clinician diagnosis of depression was assessed biennially since 2000 and newly reported regular use of antidepressants was assessed biennially since 1996. Depressive symptoms were assessed in 1992, 1996 or 2000 using the 5-item Mental Health Index from the SF-36 scale (MHI-5; severe depressive symptoms: score ≤ 52) [24], in 2004 using the 10-item Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression scale (CES-D-10; severe depressive symptoms: score ≥ 10) [25], and in 2008, 2012 and 2014 with the fifteen-item Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-15; severe depressive symptoms: score ≥ 6) [26]. The comparability of these three measures in the NHS has been shown previously [20]. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and other antidepressant classes except tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) were considered as qualifying antidepressants, since we previously found that TCAs were more likely to be prescribed for indications other than depression [23].

Covariables

Race, region of birth, highest education, husband´s highest education and father´s occupation were assessed in 1992. In 2000 the nurse´s subjective societal position [27], bodily pain and problems falling asleep or maintaining sleep were assessed, and in 2002 information on care for grandchildren, care for a disabled/ill person, and sleep duration was available. Work status, marital status, living arrangement, social-emotional support [28], the social network index [29], current physical functioning [30], comorbidity burden [21] and minor tranquilizer/benzodiazepine use were assessed at the 2004 analytic baseline and afterwards every 2–4 years. BMI, smoking status, and physical activity were assessed at baseline and thereafter every 2–4 years. Diet quality and alcohol consumption were assessed in 2002 and thereafter every 4 years. The selection of covariables was based on previous studies in the NHS [20, 21].

Analytic sample

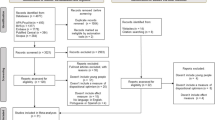

Our base population comprised women who had returned the baseline questionnaire in 2004 (N = 90,799; Fig. 1), excluding participants with missing information on any depression items in 1992, 1996 or 2000 (N = 33,156), missing information on depressive symptoms at baseline (N = 3,846), who indicated a self-reported diagnosis of depression, a regular use of antidepressants, or severe depressive symptoms (MHI-5 score ≤ 52) prior to June 1, 2004 (N = 14,346), and participants with severe depressive symptoms at baseline (CESD-10 score ≥ 10; N = 3,609).

Further, we excluded participants (N = 1,221) with missing information on some or all optimism items in 2004, and participants (N = 1,138) who had not returned all questionnaires between 1992 and 2004, had not returned any questionnaire after 2004 or had no physical exam between 2004 and 2014, leaving a final analytic sample of 33,483 participants. Participants with missing information on optimism or missing information on depressive symptoms before or at baseline were slightly older, less educated and reported worse physical health compared to those included in the current analytic sample (sTable 1).

Statistical analysis

We calculated age- and multivariable adjusted Cox Proportional hazard models to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (95%CIs) across baseline optimism quartiles [Q1(least optimistic) to Q4(most optimistic)] and for an increase of one standard deviation (SD) of the baseline optimism z-score in relation to depression incidence. We used age (in months) as the time scale in our models, and calculated person-time from the return date of the baseline questionnaire (2004) through the end of follow-up (June 1, 2014), date of depression diagnosis, death, or loss to follow-up, whichever occurred first. Multivariable models were adjusted for age, baseline depressive symptom score, educational status, birth region, race, subjective societal status/social standing, work status, living arrangement, marital status, husband´s education, father´s occupation, bodily pain, physical functioning, sleep duration, problems falling asleep or maintaining sleep, providing care for grandchildren or an ill/disabled person, multiple comorbidity and minor tranquilizer use [21]. Covariables were used at baseline and updated at each follow-up cycle; missing indicators were utilized to represent missing data in statistical models. In further analyses we estimated these associations with two more restrictive depression definitions: 1. More restrictive: clinician-diagnosed depression or antidepressants use; 2. Most restrictive: clinician-diagnosed depression and antidepressants use using separate models for each definition.

In secondary analyses, we estimated the proportion of the association between optimism and depression risk mediated by time-updated potential mediators (social-emotional support [13, 14, 28], social network index [28], and lifestyle [15]) using the publicly available %Mediate macro (https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/donna-spiegelman/software/mediate/) [31]. We stratified our models by baseline depressive symptoms [CESD-10 score: very low (< 3); low (3–5); moderate (6–10)], race [Non-Hispanic White; other], region of birth [West; Midwest; Northeast; South] [20] and age [< 65; 65–74; > 74 years] testing for heterogeneity using the likelihood ratio test. Because optimism may be higher among women without depression and the temporal relation of optimism to depression occurrence is not clear (i.e., higher optimism levels may precede or follow lower depressive symptoms), we lagged our analyses by 2 years to minimize the possibility of reverse causation. Because some items used to evaluate the constructs of optimism and depression may overlap, in sensitivity analyses, we excluded the CESD-10 item ‘I felt hopeful about the future’ and the GDS-15 item “Do you feel that your situation is hopeless?”; the presence of severe depressive symptoms was still defined using the same validated cutoffs, but without considering the aforementioned item in the scoring. Finally, to consider LOT-R’s potential bi-dimensionality [32], we investigated the three positively and three negatively worded items separately in relation to depression using one variable for each dimension.

All p-values were two-sided and considered statistically significant if p < 0.05. We used SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, United States) for all statistical analyses.

Results

Participants were aged 57–85 (mean = 69.9, SD = 6.8), rather optimistic (LOT-R: mean = 19.9, SD = 3.8) and showed very low levels of depressive symptoms (CESD-10: mean = 4.0, SD = 2.5) at baseline. Optimism correlated with younger age (Pearson´s r = − 0.11), lower levels of depressive symptoms (r = − 0.39) and better physical functioning (r = 0.14) at baseline. Compared to least optimistic women (bottom quartile), women who were more optimistic (top quartile) were more likely to not have been born in the northeast, to have received a higher education and a higher subjective societal position. Their husbands’ educational status was higher, and they were more likely to have had a father with a professional or managerial occupation. Women with higher optimism had also more social-emotional support, were more likely to be socially integrated and reported healthier behaviors. Retirement was more prevalent among less optimistic participants, as were negative health characteristics, including bodily pain and physical functioning (Table 1).

During 10-years follow-up, we documented 4,051 incident depression cases (overall incidence 14.0 cases per 1,000 person-years). In age-adjusted models, baseline optimism levels were substantially and inversely associated with risk of depression (Table 2; Q1 vs. Q4 optimism score: HR = 0.46, 95%CI = 0.42–0.51). While women with pre-existing clinical depression or severe depressive symptoms were excluded at baseline, additionally adjusting for baseline low-to-moderate depressive symptoms score attenuated the effect estimates, although they remained meaningful (Q1 vs. Q4: HR = 0.71, 95%CI = 0.64–0.78). In fully-adjusted models, socioeconomic and health depicting covariates did not appear to be important confounders in these associations (Q1 vs. Q4: HR = 0.73, 95%CI = 0.66–0.81). When considering optimism continuously, every 1-SD increase of optimism was associated with a 15% (95%CI = 12%-18%) lower risk of depression in the fully-adjusted model (Table 2).

Defining depression as either clinician-diagnosed depression OR antidepressant use (cases: N = 2,739, 9.4 cases per 1000 person-years) largely attenuated the association in fully-adjusted models when using categorical optimism levels (Table 3; Q1 vs. Q4: HR = 0.93, 95%CI = 0.82–1.05), although the association remained evident when using a continuous exposure (fully-adjusted model, per 1-SD increase: HR = 0.94, 95%CI = 0.90–0.98). When defining depression as clinician-diagnosed depression AND antidepressants use (cases: N = 1,055, 2.9 cases per 1000 person-years), the association was no longer apparent or effect estimates did not reach significance in fully-adjusted models (Table 4; per 1-SD increase: HR = 0.97, 95%CI = 0.90–1.04).

Being socially integrated, receiving social-emotional support and adopting a healthy lifestyle mediated the association of optimism with future depression risk (sTable 2). Jointly they accounted for about 10.2% (95%CI = 7.3%-14.3%) of the lower depression risk found among the women in the top versus bottom quartile of optimism.

Across groups with different baseline depressive symptom levels (sTable 3), optimism was similarly associated with a lower depression risk. When applying the more restrictive depression definitions the association appeared to be slightly stronger among participants with higher baseline depressive symptoms although some strata had a small number of cases (e.g., n = 30) (sTables 4–5). However, the relationship was similar across all age groups (sTable 6) and birth regions (sTable 7). Although the reduced risk was slightly smaller among Non-Hispanic Whites than among other racial groups combined, the likelihood ratio test was not statistically significant (e.g., Model 1, p = 0.391), suggesting that the optimism-depression relationship was comparable across race (sTable 8).

When implementing a 2-year lag time between optimism and depression incidence, effect estimates were slightly stronger (e.g., in fully-adjusted model: Q1 vs. Q4: HR = 0.70, 95%CI = 0.62–0.78; sTable 9). When trying to disentangle the conceptual overlap between the exposure and the outcome, not including the item “I felt hopeful about the future” of the CESD-10 when adjusting for baseline depressive symptoms lead to slightly stronger effect estimates (sTable 10). Not considering the item “Do you feel that your situation is hopeless” for scoring in the GDS, finally, did not affect estimates (sTable 11). The separate analysis of the three positively and three negatively worded items of the LOT-R indicated that both being more optimistic and being less pessimistic were associated with a lower depression risk (sTable 12).

Discussion

In the present study, older women who reported higher versus lower optimism at baseline had a reduced risk of incident depression throughout 10 years of follow-up, after adjustment for a wide array of potentially relevant covariates including baseline mild depressive symptoms. This association was evident irrespective of age, race and region of residence, and after lagging analyses by 2 years to reduce concerns about reverse causation. Mediation models suggested that lifestyle and social factors explained partly but not fully the association of optimism with depression risk. Applying more restrictive depression definitions that excluded self-reported severe depressive symptoms from the outcome measure, however, revealed attenuated or null estimates.

Results from primary models are in line with our hypotheses, based on findings from other prospective studies though comparability is somewhat limited due to differences in exposure and outcome assessment [7,8,9,10]. For instance, in the Zutphen Elderly Study, high vs. low optimism, assessed with a 4-item validated scale, predicted a lower cumulative incidence of depressive symptoms, as defined by a validated self-reported measure [10]. In one of the Finish Public Sector studies, higher versus lower optimism was associated with a reduced likelihood of starting antidepressant medication (HR = 0.67, 95%CI = 0.62–0.73) and a greater likelihood of stopping antidepressant use (HR = 1.18, 95%CI = 1.08–1.30) [7]. In the same cohort, higher optimism was associated with lower likelihood of initiating psychotherapy as a treatment for depression (HR = 0.57, 95%CI = 0.40–0.81); in 38,717 participants of the Finish Public Sector study the authors also found a lower likelihood of depressive disorder (HR = 0.68, 95%CI = 0.62–0.73) based on purchase of antidepressants, long-term work disability or hospitalization due to depression and after accounting for sex, age, marital status, socioeconomic position, alcohol consumption, anxiolytics and hypnotics purchase, and chronic medical conditions [8]. In other studies, optimism predicted long-term work disability with a diagnosis of depression, and the likelihood of returning to work [9]. The outcomes defined within the Finish Public Sector Study were similar to our more restrictive depression definitions. However, that they did not control for baseline depression may have rendered their results biased given that in our study, associations were attenuated, although still meaningful, after adjustment for baseline depressive symptoms.

That effect estimates were attenuated (more restrictive definition) or disappeared (most restrictive definition) in our study when using more restrictive definitions of depression (i.e., higher specificity for identifying depression) may suggest that optimism might serve as a protective factor for mild or moderate depression, but not for higher severity clinical depression. Alternatively, such attenuation in estimates may also be explained by measurement issues: associations could be stronger for self-reported depressive symptoms score because of greater variability compared to binary diagnosis/medication and allow the identification of additional depression cases (e.g. depressive participants who would not seek clinician’s help or be prescribed medication). Lastly, some optimism and depression attributes overlap conceptually; yet, estimates were stable when removing items that could characterize both optimism and depression.

We found no evidence that the association would differ importantly across baseline depressive symptoms, age, race, or region of birth. The majority of existing studies did not consider stratified analyses, except by age, with two previous studies reporting that the association of optimism and depression risk would wane with increasing age when examined over a broader age range than our study [33, 34].

Several explanations exist as to why optimists might be less prone to develop depression. First, optimism and depression might share a common genetic disposition, potentially explaining a third of the phenotypic association between them [35]. Second, childhood adversity [36] could account for the association, whereby younger individuals exposed to major stressors early in life would be more likely to develop depression and less likely to maintain an positive outlook on life. To our knowledge, no previous study has examined this hypothesis. Third, optimists were shown to maintain a healthier lifestyle [15], receive more social support [13, 14] and apply more effective coping strategies [12]. For instance, optimists are more likely to recognize and disengage from unsolvable problems and are therefore able to focus their energy on situations that are solvable, making them potentially less likely to experience avoidable disappointments [11]. In our study, the association between optimism and depression incidence was modestly mediated by social network, social-emotional support and a healthy lifestyle but these three factors individually or jointly explained only a small portion of the reported effect. Other factors, including alternative coping strategies (e.g., planning, problem-solving), might be of greater importance and should be considered in future research.

The principal strength of our study is the control of most known determinants of depression and optimism, including baseline depressive symptoms. Additional strengths are the prospective study design with 10-year follow-up, validated optimism assessment, having 3 indicators of depression, and a large number of participants, affording sufficient statistical power even for sensitivity analyses that verified the robustness of the optimism-depression association. However, because the NHS represents a highly homogenous sample of mostly white women who were all nurses, results might not be generalizable to other populations, including women in non-medical occupations and men, although incident depression rates in the Nurses’ cohort have been found to be highly consistent with expected age- and sex/gender-specific rates. Though nurses, especially experienced ones, might be considered more resilient compared to women from the general population, their major depression prevalence is roughly comparable (8.7%) [37, 38] The generalizability of our results might be reduced by high attrition rates in the study; women with missing information on optimism or depressive symptoms differed importantly from the analytic sample. Further, we had no information on other protective factors that might characterize optimistic individuals (e.g., coping strategies like planning and problem-solving) and in turn, influence depression risk, to examine their potential mediating role. Finally, although we excluded women with any depressive episode prior to or at baseline, it is likely that we did not capture all participants with a prior depressive episode since an important proportion of mood disorders have already developed by mid-adolescence [39]. Depressive symptoms might cause persistent scars in personality traits [40], such as optimism, and therefore part of our results could be explained by reverse causality.

Optimism as a potential modifiable determinant of depression risk in late life may be promising based on prior intervention research. Currently, the Best Possible Self exercise is considered the most effective strategy to increase dispositional optimism. Briefly, one imagines a future possible self, pictures this possible self and positive future situations in detail, and then creates a mental plan how to achieve this imagined self [17]. A recent meta-analysis [41] indicates that Best Possible Self interventions are effective in increasing optimism outcomes although evidence on long-term effects is currently still insufficient; and only a small non-significant effect on depressive symptoms was reported based on three interventions in young participants with one to three months of follow-up [41,42,43,44]. Long term effects on depressive symptoms, particularly in midlife and older adults, remain unknown.

Several aspects of the association between dispositional optimism and depression are still to be resolved. Future prospective studies are needed to evaluate the association between optimism and depression risk in various populations while considering other protective factors of resilience and controlling for shared genetic dispositions and childhood environment factors. Further, better understanding how and when psychological protective characteristics like optimism develop and consolidate over the life course is warranted, to eventually guide intervention research toward specific time windows that appear more potent to prevent depression risk in later life. Evidence suggests that optimism levels would be relatively similar across age groups [33] although they may start to decline around late midlife [45, 46]. Therefore, if optimism-enhancing interventions truly protect against subsequent depression risk, future clinical trials aiming to reduce the depression burden among the elderly might be ideally implemented before optimism levels start declining.

Data availability

"Further information including the procedures to obtain and access data from the Nurses’ Health Studies and Health Professionals Follow-up Study is described at https://www.nurseshealthstudy.org/researchers (contact email: nhsaccess@channing.harvard.edu) and https://sites.sph.harvard.edu/hpfs/for-collaborators/."

References

Malhi GS, Mann JJ. Depression. Lancet. 2018;392:2299–312.

Penninx BWJH, Nolen WA, Lamers F, Zitman FG, Smit JH, Spinhoven P, et al. Two-year course of depressive and anxiety disorders: results from the Netherlands study of depression and anxiety (NESDA). J Affect Disord. 2011;133:76–85.

Trudel-Fitzgerald C, Chen Y, Singh A, Okereke OI, Kubzansky LD. Psychiatric, psychological, and social determinants of health in the nurses’ health study cohorts [Internet]. Am J Public Health. 2016;106:1644–9.

Cohen BE, Edmondson D, Kronish IM. State of the art review: depression, stress, anxiety, and cardiovascular disease [Internet]. Am J Hypertens. 2015;28:1295–302.

Cuijpers P, Beekman ATF, Reynolds CF. Preventing depression: a global priority [Internet]. JAMA J Am Med Assoc. 2012;307:1033–4.

Sohl SJ, Moyer A, Lukin K, Knapp-Oliver SK. Why are optimists optimistic? Individ Differ Res. 2011;9:1–11.

Kronström K, Karlsson H, Nabi H, Oksanen T, Salo P, Sjösten N, et al. Optimism and pessimism as predictors of initiating and ending an antidepressant medication treatment. Nord J Psychiatry [Internet]. 2014;68:1–7.

Karlsson H, Kronström K, Nabi H, Oksanen T, Salo P, Virtanen M, et al. Low level of optimism predicts initiation of psychotherapy for depression: Results from the finnish public sector study. Psychother Psychosom [Internet]. 2011;80:238–44.

Kronström K, Karlsson H, Nabi H, Oksanen T, Salo P, Sjösten N, et al. Optimism and pessimism as predictors of work disability with a diagnosis of depression: a prospective cohort study of onset and recovery. J Affect Disord. 2011;130:294–9.

Giltay EJ, Zitman FG, Kromhout D. Dispositional optimism and the risk of depressive symptoms during 15 years of follow-up: the Zutphen elderly study. J Affect Disord. 2006;91:45–52.

Aspinwall LG, Richter L, Hoffman RR. Understanding how optimism works: an examination of optimists’ adaptive moderation of belief and behavior. In: Chang EC, editor. Optimism pessimism Implic theory, Research and Practice. American Psychological Association; 2004. p. 217–38.

Solberg Nes L, Segerstrom SC. Dispositional optimism and coping: a meta-analytic review. Personal Soc Psychol Rev [Internet]. 2006;10:235–51.

Karademas EC. Self-efficacy, social support and well-being: the mediating role of optimism. Pers Individ Dif. 2006;40:1281–90.

Brissette I, Scheier MF, Carver CS. The role of optimism in social network development, coping, and psychological adjustment during a life transition. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2002;82:102–11.

Trudel-Fitzgerald C, James P, Kim ES, Zevon ES, Grodstein F, Kubzansky LD. Prospective associations of happiness and optimism with lifestyle over up to two decades. Prev Med (Baltim). 2019;126:105754.

Sharpe JP, Martin NR, Roth KA. Optimism and the Big Five factors of personality: beyond Neuroticism and Extraversion. Pers Individ Dif. 2011;51:946–51.

Malouff JM, Schutte NS. Can psychological interventions increase optimism? A meta-analysis. J Posit Psychol. 2017;12:594–604.

Luijendijk HJ, Van Den Berg JF, Dekker MJHJ, Van Tuijl HR, Otte W, Smit F, et al. Incidence and recurrence of late-life depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry [Internet]. 2008;65:1394–401.

Steffens DC, Skoog I, Norton MC, Hart AD, Tschanz JAT, Plassman BL, et al. Prevalence of depression and its treatment in an elderly population: the cache county study. Arch Gen Psychiatry [Internet]. 2000;57:601–7.

Chang SC, Wang W, Pan A, Jones RN, Kawachi I, Okereke OI. Racial variation in depression risk factors and symptom trajectories among older women. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2016;24:1051–62.

Chang SC, Pan A, Kawachi I, Okereke OI. Risk factors for late-life depression: a prospective cohort study among older women. Prev Med (Baltim). 2016;91:144–51.

Scheier MF, Carver CS, Bridges MW. Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): a reevaluation of the Life Orientation Test. J Pers Soc Psychol [Internet]. 1994;67:1063–78.

Okereke OI, Cook NR, Albert CM, Van Denburgh M, Buring JE, Manson JAE. Effect of long-term supplementation with folic acid and B vitamins on risk of depression in older women. Br J Psychiatry. 2015;206:324–31.

Ananthakrishnan AN, Khalili H, Pan A, Higuchi LM, de Silva P, Richter JM, et al. Association between depressive symptoms and incidence of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis: results from the nurses’ health study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol NIH Public Access. 2013;11:57–62.

Andresen EM, Malmgren JA, Carter WB, Patrick DL. Screening for depression in well older adults: evaluation of a short form of the CES-D. Am J Prev Med Elsevier. 1994;10:77–84.

Friedman B, Heisel MJ, Delavan RL. Psychometric properties of the 15-item geriatric depression scale in functionally impaired, cognitively intact, community-dwelling elderly primary care patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:1570–6.

Adler NE, Epel ES, Castellazzo G, Ickovics JR. Relationship of subjective and objective social status with psychological and physiological functioning: preliminary data in healthy white women. Heal Psychol. 2000;19:586–92.

Kroenke CH, Kubzansky LD, Schernhammer ES, Holmes MD, Kawachi I. Social networks, social support, and survival after breast cancer diagnosis. J Clin Oncol [Internet]. 2006;24:1105–11.

Li S, Hagan K, Grodstein F, VanderWeele TJ. Social integration and healthy aging among U.S. women. Prev Med Reports. 2018;9:144–8.

Hagan KA, Chiuve SE, Stampfer MJ, Katz JN, Grodstein F. Greater adherence to the alternative healthy eating index is associated with lower incidence of physical function impairment in the nurses’ health study. J Nutr [Internet]. 2016;146:1341–7.

Banay RF, James P, Hart JE, Kubzansky LD, Spiegelman D, Okereke OI, et al. Greenness and depression incidence among older women. Environ Health Perspect [Internet]. 2019;127:027001.

Mavioğlu RN, Boomsma DI, Bartels M. Causes of individual differences in adolescent optimism: a study in Dutch twins and their siblings. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2015;24:1381–8.

Armbruster D, Pieper L, Klotsche J, Hoyer J. Predictions get tougher in older individuals: a longitudinal study of optimism, pessimism and depression. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2015;50:153–63.

Wrosch C, Jobin J, Scheier MF. Do the emotional benefits of optimism vary across older adulthood? A life span perspective. J Pers [Internet]. 2017;85:388–97.

Plomin R, Scheier MF, Bergeman CS, Pedersen NL, Nesselroade JR, McClearn GE. Optimism, pessimism and mental health: a twin/adoption analysis. Pers Individ Dif Pergamon. 1992;13:921–30.

Bradford AB, Burningham KL, Sandberg JG, Johnson LN. The Association between the parent-child relationship and symptoms of anxiety and depression: the roles of attachment and perceived spouse attachment behaviors. J Marital Fam Ther [Internet]. 2017;43:291–307. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmft.12190.

Brandford AA, Reed DB. Depression in registered nurses: a state of the science. Workplace Health Saf. 2016;64:488–511. https://doi.org/10.1177/2165079916653415.

Health NI of M. NIMH - Major Depression [Internet]. Natl. Inst. Ment. Heal. 2017 [cited 2021 Sep 20]. Available from: https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/major-depression

Klein DN, Kotov R, Bufferd SJ. Personality and depression explanatory models and review of the evidence. Annu Rev. 2011;7:269–95. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032210-104540.

Hakulinen C, Elovainio M, Pulkki-Råback L, Virtanen M, Kivimäki M, Jokela M. Personality and depressive symptoms individual-participant meta-analysis of 10 cohort studies. Depress Anxiety [Internet]. 2015;32:461.

Carrillo A, Rubio-Aparicio M, Molinari G, Enrique Á, Sánchez-Meca J, Baños RM. Effects of the best possible self intervention: a systematic review and meta-analysis [Internet]. PLoS ONE. 2019;14:e0222386.

Enrique Á, Bretón-López J, Molinari G, Baños RM, Botella C. Efficacy of an adaptation of the best possible self intervention implemented through positive technology: a randomized control trial. Appl Res Qual Life. 2018;13:671–89.

Liau AK, Neihart MF, Teo CT, Lo CHM. Effects of the best possible self activity on subjective well-being and depressive symptoms. Asia-Pacific Educ Res. 2016;25:473–81.

Manthey L, Vehreschild V, Renner KH. Effectiveness of two cognitive interventions promoting happiness with video-based online instructions. J Happiness Stud. 2016;17:319–39.

Kotter-Grühn D, Smith J. When time is running out: changes in positive future perception and their relationships to changes in well-being in old age. Psychol Aging. 2011;26:381–7.

Schwaba T, Robins RW, Sanghavi PH, Bleidorn W. Optimism development across adulthood and associations with positive and negative life events. Soc Psychol Personal Sci. 2019;10:1092–101.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grant UM1 CA186107, P01 CA87969, R01 HL034594, and R01 HL088521 from the National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. We would like to thank the following state cancer registries for their help: AL, AZ, AR, CA, CO, CT, DE, FL, GA, ID, IL, IN, IA, KY, LA, ME, MD, MA, MI, NE, NH, NJ, NY, NC, ND, OH, OK, OR, PA, RI, SC, TN, TX, VA, WA, WY. The authors assume full responsibility for analyses and interpretation of these data. The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose

Funding

Open access funding provided by Medical University of Vienna. This study was supported by grant UM1 CA186107, P01 CA87969, R01 HL034594, and R01 HL088521 from the National Institutes of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study design, to the discussion and interpretation of results and to the manuscript revision, Jakob Weitzer did the data analysis and manuscript drafting.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. We would like to thank the following state cancer registries for their help: AL, AZ, AR, CA, CO, CT, DE, FL, GA, ID, IL, IN, IA, KY, LA, ME, MD, MA, MI, NE, NH, NJ, NY, NC, ND, OH, OK, OR, PA, RI, SC, TN, TX, VA, WA, WY. The authors assume full responsibility for analyses and interpretation of these data. The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ethical approval

The study protocol was approved by the institutional review boards (IRBs) of the Brigham and Women's Hospital and Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, and the IRBs allowed participants’ completion of questionnaires to be considered as implied consent.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Weitzer, J., Trudel-Fitzgerald, C., Okereke, O.I. et al. Dispositional optimism and depression risk in older women in the Nurses´ Health Study: a prospective cohort study. Eur J Epidemiol 37, 283–294 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-021-00837-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-021-00837-2