Abstract

During the 1980s and 1990s life expectancy at birth has risen only slowly in the Netherlands. In 2002, however, the rise in life expectancy suddenly accelerated. We studied the possible causes of this remarkable development. Mortality data by age, gender and cause of death were analyzed using life table methods and age-period-cohort modeling. Trends in determinants of mortality (including health care delivery) were compared with trends in mortality. Two-thirds of the increase in life expectancy at birth since 2002 were due to declines in mortality among those aged 65 and over. Declines in mortality reflected a period rather than a cohort effect, and were seen for a wide range of causes of death. Favorable changes in mortality determinants coinciding with the acceleration of mortality decline were mainly seen within the health care system. Health care expenditure rose rapidly after 2001, and was accompanied by a sharp rise of specialist visits, drug prescriptions, hospital admissions and surgical procedures among the elderly. A decline of deaths following non-treatment decisions suggests a change towards more active treatment of elderly patients. Our findings are consistent with the idea that the sharp upturn of life expectancy in the Netherlands was at least partly due to a sharp increase in health care for the elderly, and has been facilitated by a relaxation of budgetary constraints in the health care system.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The Netherlands has been world champion of life expectancy at birth during some years in the 1930s and 1960s, but suddenly lost its advantage in the 1980s [1]. During the 1980s and 1990s a complete stagnation of mortality decline occurred in some age-groups in the Netherlands, while other high-income countries continued their rapid mortality declines. This happened both among the very young (perinatal mortality) and among the very old (80+). Stagnation of mortality at both ends of the age-spectrum started around 1980, and was noted first for perinatal mortality [2, 3] and later for old-age mortality [4–6]. Analyses of cause-of-death patterns showed that the stagnation of old-age mortality decline in the Netherlands could partly be attributed to smoking-related causes of death. The evidence also showed a contribution of ill-defined causes of death which are typical for old age (e.g. mental and neurological disorders) [7].

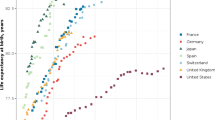

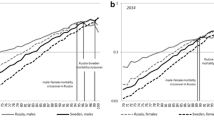

A stagnation of mortality decline among the elderly has also been observed in a small number of other countries, particularly the US and Denmark [8, 9]. Interestingly, however, progress in mortality decline among the elderly has resumed in Denmark around 1995 [10], and in the Netherlands around 2002, while the United States show no signs of a reversal yet. As Fig. 1 shows, from 2002 to 2008 life expectancy at birth in the Netherlands has increased by almost 2 years from 76.0 to 78.3 years among men, and from 80.7 to 82.3 years among women). This paper aims to assess the possible causes of the reversal from stagnation to renewed decline of old-age mortality in the Netherlands.

Life expectancy at birth, by gender, the Netherlands, 1950–2008. Source: Statistics Netherlands (http://statline.cbs.nl/statweb/)

We show that the recent upturn of life expectancy in the Netherlands can plausibly be ascribed to an expansion of health care, particularly for the elderly. Our paper therefore adds to a growing literature on the potential importance of medical care as a determinant of life expectancy in high-income countries. This has long been a topic of great controversy, based on historical analyses which suggest that other determinants, like increasing prosperity, better nutrition or public health measures, have been much more important for the secular decline in mortality [11, 12]. However, recent evidence from a range of countries suggests that medical care is increasingly important for further gains in survival, after infectious diseases had largely been eliminated as a cause of death [13–16].

Data and methods

Mortality data were extracted from the national registry kept at Statistics Netherlands, which is derived from the municipal population registries which are continuously kept up to date. Underlying causes of death were coded according to the International Classification of Diseases (9th and 10th revisions). In order to calculate age- or cause-specific contributions to gains in life expectancy we calculated the number of life years that would have been gained if only the observed age- or cause specific mortality risks would have changed during the period, keeping all other mortality risks constant. We also performed an age-period-cohort analysis to test whether changes in mortality occurring around 2002 were due to cohort- or period-effects [17, 18].

Data on determinants of mortality (sociodemographics, lifestyle, health status, health care) were extracted from registrations and surveys kept at Statistics Netherlands (CBS; data mostly available online at http://statline.cbs.nl/statweb/), the National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (RIVM), and the Health Care Insurance Board (CvZ). Age-adjusted annual percent changes and annual rate changes were calculated with regression analysis allowing for a change in trend in 2001, 1 year earlier than the change in mortality trend. Self-reported data on lifestyle, health status and health care utilization came from the national living conditions survey (POLS) which is held on a continuous basis among representative samples of the non-institutionalized population of the Netherlands. Because of substantial changes in the questionnaire only data from 2001 onwards could be used. Data on drug prescriptions came from the national registration of drugs reimbursed by public and private health care insurers (GIP database). Data on hospital admissions, clinical incidence (i.e., incidence of a first clinical episode for a particular disease) and hospital procedures came from the national registration of hospital admissions (LMR) which includes clinical as well as day care admissions. Data on health care expenditure came from detailed cost-of-illness studies for the years 1994, 1999, 2003, and 2007 which have been performed by the National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (RIVM) [19]. These studies are based on a wide range of administrative data covering all health care sectors, and data were re-analyzed to derive age- and gender-specific patterns of health care expenditure. Data on end-of-life decisions came from a series of surveys among physicians who acted as cause-of-death certifiers for a representative sample of deaths (excluding acute deaths) in 1990, 1995, 2001 and 2005 [20].

Results

As Table 1 shows, around two-thirds of the increase in life expectancy after 2002 resulted from declines in mortality among those aged 65 years and older, both in men and women. As compared to the period before 2002, an acceleration of mortality decline can be observed in nearly all age-groups, but was particularly noteworthy among the elderly. This acceleration occurred simultaneously in many age-groups, suggesting a period- rather than a cohort-effect. We tested this hypothesis in a formal age-period-cohort analysis which shows that a model allowing for a period effect is much better in explaining the mortality trend data than a model allowing for a birth-cohort effect. For both men and women the model estimate of the point in time at which a period change occurred was between 2001 and 2002 (see Web appendix 1).

Many cause-of-death groups contributed to the rise in life expectancy after 2002. Cardiovascular disease is the main contributor (life-years gained between 2002 and 2008: 0.82 years in men, 0.65 years in women), followed by symptoms and ill-defined conditions (0.16 years in men, 0.18 years in women) and by respiratory conditions (0.16 years in men, 0.05 years in women) (see Web appendix 2). For several specific causes of death clear accelerations of mortality decline, or even reversals from increasing to declining trends occurred in or around 2002 (Fig. 2). This includes diabetes, stroke, mental disorders (mainly vascular and non-specified dementia), pneumonia, and symptoms and ill-defined conditions. While the stagnation of old-age mortality during the 1980s and 1990s was partly due to smoking-related causes, the continuing increase in lung cancer mortality among women suggests that the decline of old-age mortality after 2002 was not.

We reviewed trends in a wide range of determinants of mortality, comparing developments before and after 2001 where possible. After 2001 there were very few favorable trends in sociodemographics, lifestyle or health status among the elderly. Actually, many trends were unfavorable: the age-adjusted prevalence of smoking (women only), obesity, diabetes and hypertension increased, as well as the incidence of acute myocardial infarction and stroke (see Web appendix 3). However, we did find favorable changes in health care delivery (Table 2). There were substantial increases in the age-adjusted percentage of elderly visiting a medical specialist, using prescribed drugs, being admitted to hospital, and undergoing surgery. This included treatment for cardiovascular conditions: the age-adjusted percentage of elderly receiving lipid- or blood pressure-lowering drugs or undergoing surgical procedures for cardiovascular problems increased much more rapidly between 2001 and 2007 than it did between 1995 and 2001. The most spectacular increases were seen for lipid-lowering drugs (mostly statins): for example, among men and women aged 80–84 the proportion of persons on lipid-lowering drugs increased from 7.5% in 2000 to 32.8% in 2008.

Hospital admission rates among the elderly rose only slowly during the 1990s, but the rate of increase suddenly accelerated in 2001 (Fig. 3). This acceleration occurred for many disease groups, including cancer, diseases of the nervous system, cardiovascular diseases, and injuries (results not shown). Health care expenditure per head of population rose only modestly between 1994 and 1999, but rose rapidly between 1999 and 2003 (Fig. 4). The increase was largest among the elderly, due to a rapid expansion of hospital care and care for the elderly (residential care and home care).

Hospital admission rates by age, the Netherlands, 1993–2007. Source: Statistics Netherlands (http://statline.cbs.nl/statweb/)

Survey data among Dutch physicians show that the frequency of end-of-life decisions which hasten death (euthanasia, alleviation of symptoms with high doses of morphine, and withholding or withdrawing life-prolonging treatment) rose slightly during the 1990s. Between 2001 and 2005, however, there was a strong decline in the proportion of deaths in which life-prolonging treatment had been withheld or withdrawn (Table 3). This decline was particularly noteworthy among the elderly and for treatment with antibiotics, and is seen in all causes of death (results not shown).

Discussion

We found that two-thirds of the increase in life expectancy at birth since 2002 were due to declines in mortality among those aged 65 and over, and that these declines reflect a period rather than a cohort effect, suggesting that the causal factor or factors started to act with a short rather than with a long delay. Striking accelerations or even reversals of mortality trends occurred for various causes of death, many of which are typical for old-age such as stroke, pneumonia, dementia, and symptoms and ill-defined conditions. Favorable changes in mortality determinants coinciding with the acceleration of mortality decline mainly occurred within the health care system. Health care expenditure rose rapidly after 2001, and was accompanied by a sharp rise of elderly persons seeing a specialist, using prescribed drugs, being admitted to hospital, and undergoing surgical procedures. This included sharp rises in drug and surgical treatment for cardiovascular conditions, the cause-of-death group contributing most to the rise of life expectancy. A decline of deaths following non-treatment decisions is consistent with a change in physicians’ attitudes towards more active, life-prolonging treatment of elderly patients.

The results suggest that the sharp upturn of life expectancy in the Netherlands was at least partly due to a sharp increase in health care for the elderly, and has been facilitated by a relaxation of budgetary constraints in the health care system. That a more liberal administration to elderly patients of life-prolonging treatments has played a role in mortality decline is consistent with the decline in one-year case fatality among hospital patients which has been observed in the Netherlands [21]. Between 2001 and 2005, mortality within 1 year after hospital admission declined for many conditions. Among those aged 80 years and over, the average decline (for all conditions combined) was about 14% (from 26 to 22%). This decline occurred for many conditions, including ischemic heart disease (where one-year case fatality declined from 34 to 28%) and stroke (where one-year case fatality declined from 52 to 45%) [21]. Because there was a simultaneous increase in the hospital admission rate (Fig. 3), the decline in case fatality may also, at least partly, reflect a shift towards less severely ill patients. In the case of stroke, a plausible explanation for the decline of the one-year case fatality rate (and for the acceleration of mortality) is more rapid and more aggressive treatment for stroke in specialized stroke units, which were implemented on a large scale from about 2000 onwards [22].

In the case of pneumonia, dementia, and symptoms and ill-defined conditions, a more active approach towards the treatment of seriously ill elderly patients may have played a role too. Changes in mortality from these conditions are often regarded as indicative of “artefacts” of certification or coding, but these also reflect changes in physicians’ attitudes. As coding practices within Statistics Netherlands have not been systematically documented it is difficult to exclude changes in coding practice as an explanation. To the extent that they reflect changes in certification of causes of death, however, they suggest that physician attitudes have changed over time. Deaths certified as being caused by “pneumonia” can also be interpreted as a decision by the physician not to search for a better diagnosis, or if a better diagnosis is available not to treat the patient for this disease, but to let him or her die from what has always been considered the “old man’s friend” [23]. The same applies to dementia, which as long as its complications are adequately treated will in itself not lead to death. If a death is being certified as caused by dementia, the physician has probably decided that further treatment is useless. For this very reason, dementia has long not been accepted as a possible “underlying” cause of death [24].

That the upturn of life expectancy may at least partly be due to a more liberal administration to elderly patients of life-prolonging treatments is also consistent with the results of end-of-life surveys in the Netherlands. These surveys show a strong decline in the proportion of deaths among the elderly in which life-prolonging treatment had been withheld or withdrawn (Table 3). For example, less withholding of treatment with antibiotics may have contributed to the reversal in the trend of mortality from pneumonia (Fig. 2). In these surveys, physicians were asked to estimate the amount of time by which life was shortened, and this was generally small but largest for withholding or withdrawing of life-prolonging treatment [20]. The decline of the latter practice may therefore also have had a direct effect on survival rates in the population. An international survey has shown that Dutch physicians used to have higher frequencies of making end-of-life decisions than their colleagues in other European countries [25, 26], and we have shown elsewhere that the proportion of deaths with one of these end-of-life decisions was positively correlated with mortality rates among the elderly [27].

More health care may not only have reduced old-age mortality through more in-hospital treatment and/or more active treatment of severely ill patients, but also through more liberal administration in an outpatient setting of drugs which may prevent severe illness. The increase in prescription of lipid- and blood pressure lowering drugs to elderly people may have contributed to mortality decline because both types of drugs have been shown to reduce mortality, and to do so within a few years after start of treatment [28, 29]. Liberalization of preventive drug treatment can be traced in professional guidelines, which have gradually relaxed or abolished age-limits in the prescription of these drugs. For example, in 1999, the guideline of the Dutch Society of General Practice (NHG) for prescribing cholesterol lowering drugs still included an upper age-limit of 70 years for men and 75 years for women. In 2006, the new guideline on cardiovascular risk management no longer had age-limits for cholesterol lowering or blood pressure lowering drugs [30]. In this case, the guidelines have apparently formalized changes which had already started to occur in the practice of health care.

We believe that the evidence for a contribution of increased health care delivery to the upturn of life expectancy in the Netherlands is compelling, but acknowledge that parallel trends in population-wide health care delivery and mortality indicators do not prove that one has led to the other. Individual level data, if they can be found, could be used to check whether the increases in survival really occurred among people who had received more health care, e.g. lipid-lowering drugs or PTCAs. The same applies to international comparisons of trends in determinants and trends in life expectancy.

The expansion of health care for the elderly coincided with a clear-cut change in growth of health care expenditure in the Netherlands. Long-term trends in health care spending in the Netherlands show a very distinct pattern, characterized by rapid growth in the 1960s and 1970s, relatively slow growth in the 1980s and 1990s, and rapid growth again in the first years of the new millennium. In terms of the volume of care annual growth rates were 4% in the 1970, 2% in the 1980s, 2% in the 1990s, and almost 6% in the period 2001–2007. Expressed as a proportion of Gross National Product, health care expenditure rose from about 4% in 1960 to about 9% in 1980, remained more or less stable until the year 2000, and then rapidly increased again to slightly above 10% in 2008. The annual growth rate of health care expenditure (in constant prices, i.e. adjusted for inflation) peaked in 2001, 2002, and 2003. It was 3.1% in 1999, 3.6% in 2000, 5.4% in 2001, 4.4% in 2002, 4.3% in 2003, 3.2% in 2004, 2.9% in 2005, 2.6% in 2006, and 3.1% in 2007 [31].

The sudden rise in health care expenditure after 2001 was due to a conscious decision by the Dutch government to relax the budgetary restraints of the 1980s and 1990s. During these two decades the Dutch government had successfully limited the growth of health care expenditure, first by a strict regulation of supply (hospital beds, expensive equipment, specialized personnel, …), then by imposing budget constraints for in-patient care. As a result, the proportion of GDP spent on health care in the Netherlands rose less than in many other high-income countries. As shown in Table 4, health care expenditure rose more rapidly during the 1980s and 1990s in Belgium, France, Germany, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the United States. The only other countries with similar stagnation in the proportion of GDP spent on health care were Denmark (which also experienced a stagnation in life expectancy) and Sweden [32]. By 2001 public dissatisfaction with waiting lists and other problems of access to the health care system had become so wide-spread in the Netherlands that the government decided to remove budgetary restraints. In the plan “Zorg verzekerd” (“Care insured (or ensured)”) the government promised that all necessary treatments would be eligible for reimbursement [33]. As a result, health care costs rose sharply, until new but less tight restrictions were re-imposed around 2004.

It is difficult to say whether the relaxation of budgetary constraints directly caused the expansion of health care, or only facilitated a change that had its own momentum. Conceivably, these simultaneous changes in health care delivery and health care financing reflected a change towards less complacent attitudes to health care which were shared by both professionals and policy-makers. The early years of the new millennium were not only a period of rapid economic growth which made budgetary constraints less acceptable, but also of profound changes in public opinion, accelerated by the murder of Dutch politician Pim Fortuyn in 2001. Increased responsiveness of the health care system to consumer needs therefore may have been part of broader cultural changes as well.

In conclusion, although important questions remain a plausible hypothesis for explaining the sudden reversal of old-age mortality trends in the Netherlands is more health care for the elderly, which was at least facilitated by a sudden relaxation of budgetary restraints.

References

Oeppen J, Vaupel JW. Broken limits to life expectancy. Science. 2002;296:1029–31.

Hoogendoorn D. Impressive and at the same time dissapointing decline of perinatal mortality in the Netherlands [in Dutch]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 1986;130:1436–40.

Mackenbach JP. Perinatal mortality in the Netherlands: everybody’s problem, nobody’s problem [in Dutch]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2006;150:409–11.

Nusselder WJ, Mackenbach JP. Rectangularization of the survival curve in the Netherlands, 1950–1992. Gerontologist. 1996;36:773–82.

Nusselder WJ, Mackenbach JP. Rectangularization of the survival curve in the Netherlands: an analysis of underlying causes of death. J Gerontol Soc Sci. 1997;52:S145–54.

Nusselder WJ, Mackenbach JP. Lack of improvement of life expectancy at advanced ages in The Netherlands. Int J Epidemiol. 2000;29:140–8.

Janssen F, Nusselder WJ, Looman CWN, Mackenbach JP, Kunst AE. Stagnation in mortality decline among elders in the Netherlands. Gerontologist. 2003;43:722–34.

Janssen F, Mackenbach JP, Kunst AE. Trends in old-age mortality in seven European countries, 1950–1999. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57:203–16.

Meslé F, Vallin J. Diverging trends in female old-age mortality: the United States and the Netherlands versus France and Japan. Pop Dev Rev. 2006;31:123–45.

Juel K, Bjerregaard P, Madsen M. Mortality and life expectancy in Denmark and other European countries. What is happening to middle-aged Danes? Eur J Publ Health. 2000;10:93–100.

McKeown ThF. The role of medicine: dream, mirage or nemesis. London: Nuffield Provincial Hospitals Trust; 1976.

Szreter S. The importance of social interventions in Britain’s mortality decline c. 1850–1914: a re-interpretation of the role of public health. Soc Hist Med. 1988;1:5–37.

Mackenbach JP. The contribution of medical care to mortality decline: McKeown revisited. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49:1207–13.

Mackenbach JP, Looman CWN. Secular trends of infectious disease mortality in the Netherland, 1911–1978: quantitative estimates of changes coinciding with the introduction of antibiotics. Int J Epidemiol. 1988;17:618–24.

Bunker JP, Frazier HS, Mosteller F. Improving health: measuring effects of medical care. Milbank Q. 1994;72:225–58.

Cutler DM, Rosen AB, Vijan S. The value of medical spending in the United States, 1960–2000. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:920–7.

Clayton D, Schifflers E. Models for temporal variation in cancer rates. I: age-period and age-cohort models. Stat Med. 1987;6:449–67.

Clayton D, Schifflers E. Models for temporal variation in cancer rates. II: age-period-cohort models. Stat Med. 1987;6:469–81.

Slobbe LCJ, Kommer GJ, Smit JM, Groen J, Meerding WJ, Polder JJ. Costs of diseases in the Netherlands 2003: care for Euros part 1 [in Dutch]. RIVM-report nr. 270751010. Bilthoven: RIVM, 2006.

Van der Heide A, Onwuteaka-Philipsen B, Rurup ML, Buiting HM, van Delden JJM, Hanssen-de Wolff JE, et al. End-of-life practices in the Netherlands under the Euthanasia Act. N Eng J Med. 2007;356:1957–65.

Verweij G, de Bruin A. Large decline of mortality after hospital admission for stroke and prostate cancer [in Dutch]. Statistics Netherlands Webmagazine, March 31st 2008. http://www.cbs.nl/nl-NL/menu/themas/gezondheid-welzijn/publicaties/artikelen/archief/2008/2008-2429-wm.htm Further data at CBS Statline ((http://statline.cbs.nl/statweb/).

van Exel NJA, Koopmanschap MA, Scholte op Reimer W, Niessen LW, Huijsman R. Cost-effectiveness of integrated stroke services. QJM. 2005;98:415–25.

Slaets J. ‘The old man’s friend’: differences between The Netherlands and the United States with regards to decision-making for the treatment of pneumonia in nursing home patients with dementia [in Dutch]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2007;151:905–6.

Van der Meulen A, Keij-Deerenberg I. Mortality from dementia [in Dutch]. Bevolkingstrends. 2003;51:24–8.

Van der Heide A, Deliens L, Faisst K, Nilstun T, Norup M, et al. End-of-life decision-making in six European countries: descriptive study. Lancet. 2004;362:345–50.

Löfmark R, Nilston T, Cartwright C, Fischer S, van der Heide A, Mortier F, et al. Physicians’ experiences with end-of-life decision-making: survey in 6 European countries and Australia. BMC Med. 2008;6:4.

Janssen F, van der Heide A, Kunst AE, Mackenbach JP. End-of-life decisions and old-age mortality: a cross-country analysis (letter). J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:1951–3.

Mehta JL, Bursac Z, Hauer-Jensen M, Fort C, Fink LM. Comparison of mortality rates in statin users versus nonstatin users in a United States veteran population. Am J Cardiol. 2006;98:923–8.

Perry HM, Davis BR, Price TR, Applegate WB, Fields WS, Guralnick JM, et al. Effect of treating isolated systolic hypertension on the risk of developing various types and subtypes of stroke: the Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program (SHEP). JAMA. 2000;284:465–71.

Guideline Cardiovascular risk management [in Dutch]. http://nhg.artsennet.nl/kenniscentrum/k_richtlijnen/k_nhgstandaarden/Samenvattingskaartje-NHGStandaard/M84_svk.htm.

Polder JJ. Health care expenditure as head of Janus. Trends in numbers and points of view [in Dutch]. In: Mackenbach JP, editor. Trends in volksgezondheid en gezondheidszorg. Maarssen: Elsevier; 2009.

Huber M, Orosz E. Health expenditure trends in OECD countries, 1990–2001. Health Care Financ Rev. 2003;25(1):1–22.

Anonymous. Action plan Care Ensured [in Dutch]. The Hague: Ministerie van Volksgezondheid, Welzijn en Sport, November 6th, 2000. http://www.minvws.nl/artikelen/staf/actieplan_zorg_verzekerd.asp.

Mackenbach JP, Garssen J. Renewed progress in life expectancy: the case of The Netherlands. In: Crimmins E, Preston S, Cohen B, editors. International differences in mortality at older ages. Dimensions and sources. Washington, DC: National Research Council, The National Academies Press; 2010. p. 369–84.

Acknowledgments

We thank Hans Piepenbrink (Health Care Insurance Board (CvZ)) for his assistance in providing data on the use of prescription medicines from the GIP database. Comments from other members of the Panel on this working paper are gratefully acknowledged, as well as comments on cause-of-death coding practices in the Netherlands from Dr Jan Kardaun (Statistics Netherlands, The Hague, Netherlands).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

A previous version of this paper was prepared for the National Academy of Sciences Panel on Divergent Trends in Life Expectancy in High-Income Countries [34].

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Mackenbach, J.P., Slobbe, L., Looman, C.W.N. et al. Sharp upturn of life expectancy in the Netherlands: effect of more health care for the elderly?. Eur J Epidemiol 26, 903–914 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-011-9633-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-011-9633-y