Abstract

Socioeconomic status (SES) has been widely argued to be an important predictor of students’ learning outcomes; the corollary is that low-SES students face immense challenges in their learning. The present study employed an umbrella review, comprising a thematic review and second-order meta-analysis, of 48 reviews relating SES to student learning to critically examine this argument. Results elucidate three sets of insights on the relationship between SES and student learning. First, researchers need to expand the conceptualization of SES from being an objective, individual attribute measuring hierarchical differences in access to resources to a more comprehensive construct incorporating (a) objective and subjective evaluations of (b) individual and collective SES attributes; (c) emphasizing students’ mobilization of capital; and (d) adopting a more diverse, asset-based perspective of SES. Second, the umbrella review provides a nuanced evaluation of the influence of SES in student learning. It yields a mean SES effect size of r = .22 (deemed as large with reference to educational benchmarks, expected students’ achievement gains, and percentile points in achievement tests) but SES effects may be confounded with other demographics. Third, SES needs to be examined from an ecological perspective, given the different mediating and moderating processes pertaining to SES in student learning. The results imply that policies for improving low-SES students’ learning outcomes should comprehensively address multiple factors influencing student learning and avoid a one-size-fits-all approach, enhance disadvantaged students’ access to educational opportunities and resources, affirm the strengths that disadvantaged students bring to their learning, and address structural and systemic inequalities related to poverty, classism, and segregation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The relationship between SES and student learning has attracted the attention of a broad spectrum of society, including educational researchers, policymakers, and educators for decades. Students’ SES refers to their relative access to valued economic, cultural, and social resources that contribute to valued life outcomes. It is commonly measured using parental educational attainment and occupational status, family income, and home resources (Early et al., 2020; Kim, 2019; Kim et al., 2019; Sirin, 2005). SES has perhaps been thrust into the spotlight in the middle of the last century with the publication of the influential Coleman Report (Coleman et al., 1966). Coleman et al. (1966) reported findings from a nation-wide study of more than 3,000 schools and about 600,000 students in the US indicating that schools had little influence on student achievement after controlling for students’ socioeconomic backgrounds such as students’ SES and ethnicity.

The scholarship examining the relationship between SES and student learning is characterized by different phases of development since the publication of the Coleman Report. Many researchers first focus on determining the magnitude and scope of the SES-learning association (Coleman et al., 1966) before investigating the multitude of processes that explain the SES influence (Jencks, 1972). Elucidation of these processes then leads to research examining the effectiveness of programs for improving low-SES students’ learning outcomes (Hanushek, 1994). At the turn of the century, there is renewed emphasis on the role of SES in student learning when many education systems pursue both equity and quality in student achievement (Schleicher, 2009). More recently, the influence of SES on student learning can also be contextualized in the emerging discourse on social justice which underscores the importance of addressing multiple challenges (including SES and other sources of inequity) confronting low-SES students to create a more inclusive society (Kim et al., 2019; Richardson et al., 2020; Tucker-Drob & Bates, 2016).

Contextualized in this decades-long scholarship on SES in student learning, the present study employs an umbrella review to synthesize findings from previous reviews for elucidating the relationship between SES and student learning. There are five research questions (RQs):

-

1.

How do researchers conceptualize and measure SES?

-

2.

What is the relationship between SES and student learning (including effect sizes)?

-

3.

What variables mediate the SES influence on student learning?

-

4.

What relationships between different variables and student learning do SES moderate?

-

5.

What variables moderate the relationship between SES and student learning?

Figure 1 depicts the conceptual framework summarizing the umbrella review.

Importance of Study

In view of this substantial scholarship on the relationship between SES and student learning, it is not surprising to see many efforts to synthesize the literature. However, many of these reviews (Table 1) tend to focus on specific aspects of the relationship between SES and student learning, thereby precluding the derivation of comprehensive insights. For example, some reviews focused on SES measurement issues (Avvisati, 2020; Bradley & Corwyn, 2002; Cowan et al., 2012; Ensminger & Fothergill, 2003; Khavenson, 2018; Long & Renbarger, 2023; Mueller & Parcel, 1981; Willms & Tramonte, 2019), specific student populations and contexts (Abduh et al., 2023; Banerjee, 2016; Chang & Shih, 2023; de la Cruz-Campos et al. 2023; Early et al., 2020; Gerhardstein et al., 2012; Hunt & Seiver, 2018; Kaya & Selvitopu, 2023; Kim et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2020; Lotkowski et al., 2004; Machin et al., 2013; Mehana & Reynolds, 2004; Mishra, 2020; Nelson & McMaster, 2019; Nunes et al., 2022; Pinquart & Ebeling, 2020; Richardson et al., 2020; Rodriguez-Hernandeza et al. 2020; Tan et al., 2020; Tucker-Drob & Bates, 2016), specific subjects or outcomes (Banerjee, 2016; de la Cruz-Campos et al. 2023; Early et al., 2020; Fleming & Malone, 1983; Lotkowski et al., 2004; Machin et al., 2013; Mehana & Reynolds, 2004; Nelson & McMaster, 2019; Parker et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2023), or a specific SES indicator (Avvisati, 2020; Goldberg et al., 2008; Rubin et al., 2014; Tan et al., 2020). Other reviews were meta-analyses aimed at determining effect sizes between SES and students’ learning outcomes (Ciftci & Melis Cin, 2017; Fleming & Malone, 1983; Harwell et al., 2017; Kaya & Selvitopu, 2023; Kim, 2019; Kim et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2020, 2022; Nunes et al., 2022; Selvitopu & Kaya, 2021; Tan et al., 2019, 2023; Tucker-Drob & Bates, 2016; White, 1982). There were also reviews elucidating processes underpinning the SES influence on student learning (Abduh et al., 2023; Bradley & Corwyn, 2002; Hunt & Seiver, 2018; Kim, 2019; Kuncel et al., 2010; Rudd et al., 2021; Tucker-Drob & Bates, 2016; Waithaka, 2014).

The separate lines of inquiry, with different research foci and often using specific review methodologies (e.g., qualitative reviews focusing on reasons and processes and quantitative reviews focusing on determining effect sizes), characterizing past reviews eventuate in a conspicuous knowledge gap. The knowledge gap pertains to the absence of a comprehensive, contextualized understanding of the different aspects of SES related to student learning. For example, it is insufficient to merely determine the effect size of the association between SES and student achievement because the SES measurement may suffer from cultural bias against marginalized families (Long & Renbarger, 2023). Furthermore, low-SES students may not do well in schools because they also have to confront with other demographic challenges related to their race/ethnicity, immigrant status, and neighborhood poverty (Hunt & Seiver, 2018), so the SES effect size may reflect other non-SES challenges confronting low-SES students. Lastly, understanding the influence of SES on student learning also requires evidence on whether low-SES families can benefit from educational interventions and overcome their adverse environments (Machin et al., 2013).

The present study addresses this knowledge gap by conducting an umbrella review of these reviews on the relationship between SES and student learning. This umbrella review comprehensively examines different aspects such as the conceptualization and measurement of SES, SES influence on different learning domains and subject areas, different processes mediating the SES influence on student learning, relationships between variables and student learning that SES moderates, and different variables that moderate the relationship between SES and student learning. Thematic analysis is employed to examine most of these aspects except for two which are examined via a second-order meta-analysis. These two aspects are determining (a) the effect size for the association between SES and students’ learning outcomes and (b) moderating effects of the types of SES indicators, types of learning outcomes, students’ grade levels, and year of primary studies on the association between SES and students’ learning outcomes. It is expected to contribute to the SES scholarship by clarifying trajectories of conceptualizations and measurement of SES over time and ascertaining if these trajectories are culturally inclusive; determining the SES effect size in student learning; demonstrating the potential of using an ecological perspective to understand the SES influence in student learning (with the identification of mediating and moderating processes pertaining to SES); and identifying emerging perspectives in the SES-learning scholarship.

The study is important for three reasons. First, it reviews the extant literature to identify different processes that mediate SES effects on student learning, thereby elucidating how economic stress affects parenting in low-SES families (family stress model) and what high-SES parents do to support their children’s learning (family investment model). Second, policymakers in many education systems emphasize the importance of equitable learning opportunities (for low-SES students) in addition to high levels of student achievement (Schleicher, 2009). In this regard, it is important to examine SES given its influence on students’ access to educational resources, opportunities, and experiences, and its interactions with other individual, family, school, and systems-level factors to impact student learning. Therefore, the present study is timely for us to gain insights on how ensuing systems-level improvements in school quality and educational opportunities for all students in many education systems have mitigated the influence of SES on student learning. Specifically, it is important to understand whether these educational improvements have disrupted the seemingly ‘persistent’ association between SES and student learning over time. Lastly, an integral aspect of the SES scholarship is to determine the effectiveness of interventions and programs designed to help disadvantaged students (Machin et al., 2013; Mishra, 2020). Therefore, it is important for the present study to understand whether low-SES students benefit from these endeavors to enjoy positive learning outcomes.

Method

The present study employed an umbrella review of qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-methods reviews of the relationship between SES and students’ learning outcomes. In contrast to reviews which summarize findings on a specific aspect of a topic from primary studies, an umbrella review synthesizes findings from these reviews to derive comprehensive insights on different aspects of a topic (Cant et al., 2022; Grant & Booth, 2009). As the results section will show, the umbrella review (Post et al., 2019) enabled us to (a) clarify the construct of SES (including identifying emerging perspectives); (b) critically evaluate the magnitude of the SES influence on student learning; and (c) establish boundary conditions for SES by elucidating processes that underpinned the SES influence on student learning, relationships between variables and student learning moderated by SES, and variables that moderated the SES influence.

Study Identification

The research team searched for reviews and meta-analyses (published, unpublished) examining the relationship between SES and students’ learning using nine computer databases (Academic Search Complete, Australian Education Index, British Education Index, Education Full Text, ERIC, Families & Society Studies Worldwide, PsycArticles, Scopus, Web of Science) in October 2023. The search terms used pertained to SES (social class OR social status OR socioeconomic status OR socio-economic status OR SES), students’ learning outcomes (student learning OR student achievement OR academic achievement OR academic performance OR academic success OR grade* OR GPA OR growth OR attainment OR college completion OR graduation OR socioeconomic gap* OR SES gap* OR socioeconomic achievement gap* OR SES achievement gap* OR income achievement gap*), and reviews (review of literature OR literature review OR meta-analysis OR systematic review). This search from the nine computer databases returned 790 potential studies. These studies were supplemented by complementary searches that include manual searches of studies in six educational and psychology review journals (Asia Pacific Education Review, Oxford Review of Education, Review of Educational Research, Educational Research Review, Educational Psychology Review, Educational Review), a network search of relevant researchersFootnote 1 in the field of SES and student learning, and an ancestry search of reviews. These manual searches returned another 33 potential studies. The total number of potential studies from the computer databases and manual searches was 823.

A set of inclusion and exclusion criteria was used for deciding whether the studies should be included in the umbrella review. Studies were included if they (a) were qualitative, quantitative, or mixed-methods reviews; (b) examined the influence or mediators of SES in student learning; (c) examined students’ learning outcomes as measured by academic achievement/attainment/growth, college retention/dropout, or pre-K children’s operant learning outcomes; (d) involved students from pre-K to university levels; and (e) were written in English. Studies were excluded if they (a) were primary studies or studies examining secondary data; (b) examined aggregate levels of SES (e.g., school SES); (c) examined non-SES-related predictors or mediators of student learning; (d) examined students’ non-learning outcomes (e.g., behavior); or (e) were duplicates.

Selection of Studies

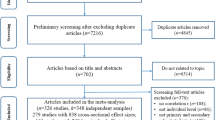

The titles and abstracts of the potential studies were screened to identify potential studies for inclusion in the analysis. This process excluded 708 studies, leaving 115 studies for further examination. The author (principal investigator) and a senior PhD student specializing in educational inequality then independently reviewed the full text of ten of the studies and discussed whether these studies were eligible to be included based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The percentage absolute inter-rater agreement was 70%. Disagreements were resolved through discussions by clarifying and adhering strictly to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. After that, the author reviewed the remaining 105 studies to decide if they should be included for the umbrella review. This process excluded 67 studies. Therefore, a final pool of 48 studies were included in the umbrella review (Fig. 2).

Coding Procedure

A formal coding scheme was developed to record substantive and methodological details from the studies:

-

Study identification details (author(s), publication year, title of study)

-

Types of publications (journal article, book, book chapter, report)

-

Use of Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) (Yes, No).

-

Use of inclusion/exclusion criteria for selection of studies (Yes, No)

-

Number of coders

-

Analytical approaches (literature review, systematic review, meta-analysis, mixed-methods review).

-

Countries/Regions

-

Conceptualization and measurement of SES

-

Types of students’ learning outcomes

-

Relationships between SES and students’ learning (e.g., effect sizes)

-

Variables which mediated the SES influence on student learning

-

Relationships between different variables and student learning that were moderated by SES

-

Variables which moderated the relationship between SES and student learning

The following four variables were examined as moderators in the association between SES and students’ learning outcomes in a second-order meta-analysis:

-

Types of SES indicators examined in meta-analyses (parental education (k = 13), parental occupational status (k = 8), family income (k = 9), home resources (k = 9))

-

Types of students’ achievement outcomes examined in meta-analyses (language (k = 9), science/technology/engineering/mathematics (STEM) (k = 14))

-

Students’ grade levels in meta-analyses (kindergarten-elementary school (k = 15), secondary school (k = 10), high school (k = 7), university (k = 2))

-

Year of primary studies examined in meta-analyses (before 1950 (k = 1), 1950 to 1959 (k = 1), 1960 to 1969 (k = 1), 1970 to 1979 (k = 1), 1980 to 1989 (k = 1), 1990 to 1999 (k = 3), 2000 to 2021(k = 8))

The author and the PhD student independently coded the 48 reviews. The percentage inter-rater absolute agreement was satisfactory: 73.91–100% except for the coding on SES measurement (63.04%) and identification of specific student populations and contexts covered in the reviews (69.57%). All coding differences were discussed and resolved consensually by clarifying mutual understanding of terms and re-reading of the reviews.

Thematic Analysis

Apart from using meta-analysis to determine (a) the effect size for the association between SES and students’ learning outcomes (RQ2) and (b) moderating effects of types of SES indicators, students’ achievement outcomes and grade levels, and publication year of primary studies included in meta-analyses (in RQ5), the six-phase thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2020) was used to analyze the reviews to address the other RQs. In the first phase, the studies were read, and initial ideas were noted. Second, they were analyzed to generate initial codes. Third, potential themes were identified from the codes. After that, the themes were further developed and reviewed to ensure that they elucidated insights on one or more of the following aspects: conceptualization of SES, measurement of SES, different students’ learning outcomes influenced by SES, the distribution of effect sizes for the association between SES and student learning, processes mediating the SES influence on student learning, relationships between different variables and student learning that were moderated by SES, and variables that moderated the relationship between SES and student learning.

Second-order Meta-analysis

Effect sizes from meta-analyses that examined the relationship between students’ SES and their learning outcomes were synthesized using a second-order three-level meta-analysis. Among the 26 meta-analyses (including two in mixed-methods reviews) included in the umbrella review, four did not report sufficient effect size data. Additionally, seven meta-analyses did not examine the SES-student learning outcomes association but investigated moderating effects of SES in associations between other variables and students’ learning outcomes. Therefore, only 15 meta-analyses were included in the second-order meta-analysis (Ciftci & Melis Cin, 2017; Fleming & Malone, 1983; Goldberg et al., 2008; Harwell et al., 2017; Kaya & Selvitopu, 2023; Kim, 2019; Kim et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2022; Nunes et al., 2022; Rodríguez-Hernándeza et al., 2020; Selvitopu & Kaya, 2021; Sirin, 2005; Tan et al., 2019; White, 1982).

In contrast to a first-order meta-analysis which combines results from quantitative empirical studies to obtain an average measure of relationships (Glass et al., 1981), a second-order meta-analysis is a synthesis of comparable first-order meta-analyses that investigate similar relationships (Schmidt & Oh, 2013). The use of three-level meta-analysis (van den Noortgate et al., 2013, 2014), via R (Viechtbauer, 2015) addresses the limitations associated with conventional meta-analysis used in most syntheses. Conventional meta-analyses address the requirement of effect size independence by averaging the dependent effect sizes within a study, selecting only one effect size for each study, or selecting one unit of analysis and averaging effect sizes within that unit. These different analytical approaches result in biased effect sizes or a loss of information that can otherwise be used to obtain more accurate effect sizes. In contrast to conventional meta-analysis, all relevant effect sizes can be included in a three-level meta-analysis, with the correlations among the effect sizes being appropriately accounted for, thereby yielding unbiased estimates of true effect sizes. Specifically, a three-level meta-analysis incorporates different variance components associated with different levels of the meta-analytic model: sampling variance of effect sizes at level 1 (in meta-analyses examined), variance between effect sizes from the same meta-analysis at level 2 (e.g., effect sizes corresponding to SES for the same children’s outcome or effect sizes corresponding to associations between a SES variable and multiple children’s outcomes reported in the same meta-analysis), and between-meta-analysis variance at level 3. In the present study, the mean number of effect sizes per first-order meta-analysis was 1.4 (21 effect sizes from 15 first-order meta-analyses) and four meta-analyses had more than one effect size, thereby justifying the use of a three-level meta-analysis.

The random effects model was employed because (a) the true effect size was expected to vary from study to study, depending on the contextual and methodological characteristics of the studies; (b) it does not require that effect sizes come from the same underlying population; (c) it enables the generalization of results beyond the studies examined; and (d) results will be identical to those from a fixed effect model even if the observed variance in effect sizes across studies is due to random sampling errors (Borenstein et al., 2009).

A total of 21 effect sizes were analyzed using the metafor package in RFootnote 2 (Viechtbauer, 2015). These effect sizes comprised 20 Pearson’s correlations (r’s) and 1 Cohen’s d. All effect sizes were converted to Fisher’s z. Effect sizes in Fisher’s z were weighted by the inverse of their variance in the analysis. The weighting enabled effect sizes from larger-sample studies (smaller variance, higher reliability) to be given more weight than those from smaller-sample studies. Effect sizes were then converted back to Pearson’s correlations in the reporting of results. Pearson’s correlations were used as the metric for reporting effect sizes because the aim was to examine associations between SES and students’ learning outcomes. Meta-regressions were performed to examine whether SES effect sizes varied with types of SES indicators, types of students’ learning outcomes and grade levels, and year of primary studies.

Results

Overview of Studies

The umbrella review examined 48 reviews comprising 24 meta-analyses, 10 systematic reviews, 12 literature reviews, and 2 mixed-methods reviews (Supplementary Table 1). These reviews came from 43 journal articles, 3 book chapters, 1 book, and 1 report. 18 of these reviews reported their identification and selection of studies using PRISMA. 27 reviews reported the use of inclusion and exclusion criteria, 5 reported the use of inclusion criteria only, and 3 others reported the use of exclusion criteria only in the selection of studies. 21 reviews involved more than one coder. 37 of the reviews examined studies with international samples (i.e., involving samples from more than one country); 5, 3, 1, 1, and 1 reviews examined studies with US, UK, China, Spain/Andalusia, and Indonesian samples only respectively.

Conceptualization and Measurement of SES

The umbrella review elucidates subtle shifts in how researchers conceptualized and measured SES in previous reviews on SES and students’ learning outcomes (Table 2). These shifts are, namely, adding subjective indicators to objective indicators for measuring SES, recognizing the individual and collective attributes of SES, emphasizing students’ mobilization of capital instead of mere access to resources, and progressing from a hierarchical, deficit perspective to a diverse, asset-based perspective of SES.

Objective versus Subjective SES Indicators

Researchers have traditionally measured SES using parental education and occupational status, family income, and home resources. These data are arguably more objective but are nonetheless subjected to three key limitations (Rubin et al., 2014). First, the objective measures of SES derived have to be interpreted using population-based benchmarks which are difficult to establish (e.g., problems of deciding cutoffs for SES categories, varying benchmarks across time and contexts). Second, using parental data to infer student SES is less relevant for older students. Lastly, students may perceive themselves as having a SES that is different from what the objective data suggest.

More recently, some researchers have begun to measure SES using individuals’ subjective perceptions (e.g., Liu et al., 2004) in addition to objective data (Rubin et al., 2014). The use of these subjective perceptions acknowledge that ‘social class can have multiple meanings in people’s lives and that social class may be conceptualized differently, depending on experience and intrapsychic and contextual factors’ (Liu et al., 2004, p. 95). To illustrate, some researchers use the MacArthur Scale of Subjective Social Status (Adler & Stewart, 2007) where respondents indicate their perceptions of their (a) education, occupational status, and income, relative to other people in their country and (b) social standing in their community using a 10-runged ‘social ladder’ (with higher rungs corresponding to higher SES). However, subjective SES measures are not impervious to criticisms (Cowan et al., 2012; Rubin et al., 2014). First, they may not be valid because individuals do not know what SES category they belong to or they may be unable to differentiate between different combinations of SES characteristics (e.g., high-income, lowly educated earners versus highly educated, middle-income earners). Second, most individuals may tend to identify themselves as ‘middle class’. Lastly, their perceptions may be affected by their mood or reference groups.

Individual versus Collective Attributes

Researchers have measured SES as an individual attribute but there are calls for recognizing the collective attributes of SES (e.g., with respect to schools or the neighborhood) to incorporate intersectional influences (e.g., race/ethnicity, regionality) (Ensminger & Fothergill, 2003; Rubin et al., 2014). In particular, including school or neighborhood SES information recognizes that students can benefit from resources available from their schools or the community in addition to those from their family (Cowan et al., 2012). To illustrate, Chetty et al. (2016) used data from the Moving to Opportunity experiment to show that when younger students moved to lower-poverty neighborhoods, they enjoyed better college attendance and earnings and were less likely to be single parents in future. In another study, Mohammadpour and Ghafar (2014) found that student-level SES was the second most important student-level predictor of student-level mathematics achievement for eight-graders in 48 countries. Country-level SES was the most important predictor of national mean mathematics achievement. School-level SES was also a key predictor of school-level mathematics achievement. However, some researchers caution against committing the ecological fallacy when we assume homogeneity in inferring student SES from aggregated SES data (Robinson, 1950; Tan et al., 2023).

Access to Resources versus Mobilization of Capital

There is a gradual trend of researchers shifting from measuring SES using students’ access to resources to the mobilization of capital to benefit their learning. Specifically, most reviews have conceptualized SES as students’ access to different types of resources that benefit their learning and used four indicators to measure this access, namely parental education and occupational status, family income, and home resources, or a composite of two or more of these resources (Bradley & Corwyn, 2002; Harwell et al., 2017; Kaya & Selvitopu, 2023; Kim et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2020, 2022; Long & Renbarger, 2023; Rodríguez-Hernándeza et al., 2020; Selvitopu & Kaya, 2021; Sirin, 2005; White, 1982). Long and Renbarger’s (2023) identified parental educational attainment and occupational status and family income as the most used measures for SES. In addition to the four commonly used SES indicators, some studies used other measures related to poverty, housing tenure, and even home atmosphere to measure SES (White, 1982). Researchers analyzing large international educational data in the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) commonly used the Economic, Social and Cultural Status (ESCS) Index to measure SES (Avvisati, 2020; Early et al., 2020). The ESCS is a composite SES measure using data on parental education and occupational status and household possessions (Avvisati, 2020).

In contrast to students’ access to familial resources, some recent reviews conceptualize SES as students’ mobilization of various forms of capital (Long & Renbarger, 2023; Mishra, 2020; Tan et al., 2019; Waithaka, 2014). For example, Lindo (2014) used indicators of human, financial, and social capital as family background measures. They found that, compared to traditional SES measures, these indicators explained as much or more variance in comprehension levels of struggling 2nd-6th graders. The notion of ‘capital’ necessitates resources to benefit student learning; access per se to resources is necessary but insufficient. The various forms of capital (Waithaka, 2014) included economic (e.g., financial resources), cultural (objectified, embodied, institutionalized forms; Tan et al., 2019), and social capital (information-related social capital, social support; Mishra, 2020). The measurement of SES using different forms of capital can be framed from Bourdieu’s (1986) theory emphasizing how differences in cultural, economic, and social resources, primarily transmitted by parental socialization of their children at home, that eventuate in differences in student learning in school. In particular, high-SES students acquire more of the cultural and social capital that is valued by schools and society (e.g., academic language, critical thinking, social networks), thereby affording them an advantage in their learning. Long and Renbarger (2023) found that there was a shift from the use of social to cultural and economic capital in the measurement of SES over time (1916–2020).

Hierarchical, Deficit versus Diverse, Asset-based Perspective

The last shift in conceptualizing and measuring SES is related to a hierarchical, deficit versus diversity, asset-based perspective. Traditionally, hierarchical differences in access to valued resources in society for different SES groups in a stratified society can be explained by the conflict (e.g., few in the top socioeconomic positions exploiting many) or functionalist (e.g., monetary and prestige differences are necessary to motivate investment training and development) perspective (Mueller & Parcel, 1981).

Long and Renbarger (2023) noted that some SES researchers lament about existing SES indicators not reflecting agency for specific groups of marginalized individuals and therefore, suffering from a deficit perspective when viewed from the community cultural wealth model (Yosso, 2005). Proponents of this model argue that individuals’ SES should not be assessed based on the standard of the White, middle class and that an inclusive assessment of SES should recognize the unique, diverse resources that racial/ethnic minorities mobilize to succeed despite oppressive systems. These resources include aspirational (possessing high goals), navigational (traversing the educational system not designed for racial/ethnic minorities), familial (learning from broad individuals beyond the immediate family), resistant (challenging unfair educational system), social (learning from communal networks), and linguistic (using multiple languages) resources. Harper’s (2010) study exemplified how some researchers have moved from a deficit-oriented to an anti-deficit achievement framework to examine enablers of STEM achievement for students of color for three pipeline points (pre-college socialization and readiness, college achievement and post-college persistence in STEM). For example, a deficit-oriented question ‘Why are they so underprepared for college-level mathematics and science courses?’ could be reframed as ‘How do STEM achievers from low-resource high schools transcend academic under-preparedness and previous educational disadvantage?’.

SES Measurement Issues

The umbrella review identifies some key issues on SES measurement as raised by various researchers. The first issue is related to many surveys asking students to provide information on their parents’ education and occupation and family income in many studies. The challenge is that most students may not know their parents’ education attainment or family income as much as their parents’ occupation (Khavenson, 2018; Willms & Tramonte, 2019). Additionally, compared to older students, young children are less able to indicate the education and profession of their parents accurately (Khavenson, 2018).

Second, researchers are divided as to whether we should adopt a reflective or formative approach in measuring SES. Researchers using a reflective approach assume that SES, as a latent variable, influences levels of observable indicators such as parents’ education and occupation status and family income (Cowan et al., 2012; Willms & Tramonte, 2019). In contrast, researchers using a formative approach identifies variables influencing on students’ outcomes as SES indicators; some critics argue that this approach entails circularity and compromises the explanatory value of the SES variable (Cowan et al., 2012; Willms & Tramonte, 2019).

The third issue is about how to determine poverty thresholds (Willms & Tramonte, 2019). Researchers can employ a population-based approach by computing the distribution of SES scores in the population and using some criteria to decide the cut-point. Alternatively, they can use a scale-based approach where the cut-point depends on the item difficulty of specific SES items or the response scale categories. A third option is to use student outcomes to determine the cut-point (e.g., the SES cut-point corresponding to low-birth weight children who have health issues).

Lastly, some researchers may decide to use one set of SES indicators for very low-SES students and another for high-SES students. Another issue is whether to measure SES using one or multiple indices (Avvisati, 2020; Cowan et al., 2012; Ensminger & Fothergill, 2003). Using a single continuous measure for SES enables researchers to compare SES levels of different students easily (Cowan et al., 2012). Relatedly, Avvisati (2020) discussed the merits of using ESCS as a causal formative latent variable (i.e., a latent variable caused by the observed measured indicators) or a composite formative latent variable (i.e., a variable summarizing observed measured indicators) to measure SES in the context of PISA. In contrast, it is difficult to compare student performance at different SES levels (e.g., SES quartiles, profiles, or classes) with multiple SES measures (Avvisati, 2020).

Fifth, researchers highlight the importance of measurement invariance. For example, SES measures should be consistent across sub-populations (different grade levels; immigrant and non-immigrant students; rural and urban settings; low-, middle- and high-income countries) while being sufficiently fine-grained to differentiate status and opportunities for individuals in extreme poverty (Cowan et al., 2012; Willms & Tramonte, 2019). There are difficulties of comparability when the types of physical items asked in SES measurement change over time to include more technological items (e.g., computers) (Long & Renbarger, 2023).

Lastly, there is the problem of missing data when only one parent is present in families (Willms & Tramonte, 2019). For example, researchers have to take the scores of the only parent for parental education and occupational status when it is desirable to have those for both parents.

Influence of SES on Students’ Learning Outcomes

The umbrella review shows that SES influenced different students’ learning outcomes. These outcomes include academic achievement (Abduh et al., 2023; Chang & Shih, 2023; Ciftci & Melis Cin, 2017; Goldberg et al., 2008; Harwell et al., 2017; Kaya & Selvitopu, 2023; Liu et al., 2020, 2022; Nunes et al., 2022; Rodriguez-Hernandeza et al., 2020; Tan et al., 2019; Tucker-Drob & Bates, 2016; White, 1982), especially mathematics and science achievement (Banerjee, 2016; Fleming & Malone, 1983; Wang et al., 2023), academic attainment (Early et al., 2020; Machin et al., 2013; Richardson et al., 2020), achievement and attainment (Kim et al., 2019; Tan et al., 2023), early operant learning (Gerhardstein et al., 2012), college retention (Lotkowski et al., 2004), and dropout in higher education (de la Cruz-Campos et al., 2023).

Student-level SES Effect Size

The second-order three-level meta-analysis synthesized effect sizes on the relationship between students’ SES and their learning outcomes from 15 meta-analyses (Ciftci & Melis Cin, 2017; Fleming & Malone, 1983; Goldberg et al., 2008; Harwell et al., 2017; Kaya & Selvitopu, 2023; Kim, 2019; Kim et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2020, 2022; Nunes et al., 2022; Rodríguez-Hernándeza et al., 2020; Selvitopu & Kaya, 2021; Sirin, 2005; Tan et al., 2019; White, 1982). Results showed that the mean effect size for the random effects model was r = 0.22, p < 0.001, 95%CI = (0.17, 0.26). A common concern in meta-analyses is the presence of publication bias in studies (Polanin et al., 2016). This means that studies with significant effects are more likely to be published than those with nonsignificant effects. The funnel plot of standard errors by effect sizes showed that effect sizes from individual meta-analyses were distributed on both sides of the mean effect size and that there were effect sizes corresponding to studies with different standard errors (Fig. 3). Published studies tend to report significant effect sizes from larger sample sizes, and the latter are associated with smaller standard errors (Polanin et al., 2016). Therefore, another way to detect publication bias is to examine if SES effect sizes vary with the size of standard errors. Results of moderator analysis indicates that standard errors were not a significant moderator for SES effects (β = 0.49, p = 0.61). The funnel plot and moderator analysis results show that there is no evidence of publication bias in the data.

Processes Mediating the SES Influence

The umbrella review identifies many processes that mediated the SES influence on student learning (Table 2). Four reviews primarily used an ecological perspective to analyze these processes (Banerjee, 2016; Bradley & Corwyn, 2002; Chang et al., 2023; Kuncel et al., 2010). The processes are related to student self-concepts, reactions to stress-inducing conditions, home and parental factors, school and teacher factors (e.g., stereotypes from teachers and peers), and environmental support (including access to material and social resources).

Specifically, Abduh et al. (2023) found that low-SES students had difficulty accessing familial resources, suffered from lower levels of self-concepts, and were perceived more negatively by teachers and peers. Banerjee (2016) reported that disadvantaged students suffered from a lack of positive environment and support related to the family, teachers, and schools. Bradley and Corwyn (2002) identified differences in access to material and social resources and reactions to stress-inducing conditions by parents and children as mechanisms explaining how SES influenced a variety of student outcomes (including learning). In contrast to these reviews, Kuncel et al. (2010) did not find that students’ test scores, as a proxy for individual differences, was related to their SES. Specifically, Kuncel et al. (2010) reported evidence from Sackett et al. (2009) examining eight data sets (including three large longitudinal high school samples). Results showed that the association between students’ test scores and grades was largely unchanged (from r = 0.47 to r = 0.44 when SES effects were controlled), thereby indicating that test scores did not reflect SES effects in student learning.

The findings summarized by Abduh et al. (2023), Banerjee (2016), and Bradley and Corwyn (2002) could be understood from three theories. First, the notion of low-SES students having lower levels of self-concepts, and therefore under-performing in schools, can be understood from Bandura’s (1986) social cognitive theory which suggests that student learning is influenced by cognitive processes such as motivation, self-efficacy, and goal orientation. These cognitive processes are shaped by environmental factors and personal experience. SES constitutes one of these important environmental factors and it shapes students’ personal experiences. For example, low-SES students may have less access to positive role models, feedback, and support that can enhance their cognitive processes and self-regulation in learning.

The idea of attributing SES differences in student learning to differences in access to material and social resources and reactions to stress-inducing conditions in Bradley and Corwyn’s (2002) review can be understood from the family stress and investment models. The family stress model (Conger, 2005) argues that parents with economic hardship (e.g., low-SES parents) have less resources to purchase goods and services to support their children’s learning. These parents also experience poorer emotional wellbeing (e.g., demoralization, distress, anger, anxiety, stress, frustration) which affects parenting quality (e.g., via use of inconsistent or negligent parenting practices) and parent–child relationship (e.g., less sensitive or warm) (Maserik & Conger, 2017). This diminished parental investment (Conger & Donnellan, 2007) adversely affects their children’s development (including school learning).

The findings that SES differences in student learning were due to teacher and school processes from Abduh et al. (2023) and Banerjee’s (2016) reviews can be understood from the resource dilution theory (Downey et al., 2004). The theory explains how low-SES students may be disadvantaged in their learning because of inadequate teacher and school resources (e.g., school leadership, teachers, infrastructure, materials, school climate) in disadvantaged schools (Downey et al., 2004).

SES Moderating Relationships between Different Variables and Students’ Learning Outcomes

Results from the umbrella review show that many reviews synthesized findings on whether SES moderated relationships between different variables (student characteristics, parental influences, school processes, and the effectiveness of interventions) and student learning (Table 3). First, three reviews showed that compared to low-SES peers, high-SES students benefited more from different personal variables in their learning. Parker et al. (2020) meta-analyzed 176 studies on gender differences in expectancy value theory constructs for science, mathematics, and technology domains. Results showed that gender gaps in mathematics and science learning were larger for high-SES (versus low-SES) students. Tucker-Drob and Bates’ (2016) meta-analysis involving 14 studies found that students’ genetic endowment contributed more to their cognitive ability for high- as compared to low-SES students in the US. In contrast, gene X SES effects were nonsignificant or revised in studies in Western Europe and Australia characterized by more universal access to quality education. Hansford and Hattie (1982) found that SES positively moderated associations between student self-measures and achievement in their meta-analysis of 128 studies.

The second set of reviews showed that compared to low-SES peers, high-SES students benefited more from many parental influences. For example, Pinquart and Ebeling’s (2020) meta-analysis of 169 studies found that associations of parental expectations with students’ academic achievement were stronger for high-SES (as compared to low-SES) parents. Tan et al.’s (2020) meta-analysis of 98 studies found that associations between three types of parental involvement practices (parental learning support at home, parental academic emphasis, parent-teacher communication) and student achievement were stronger for parents who were more educated. In another review, Goldberg et al. (2008) examined how SES moderated different aspects of parental and resources influence related to parental employment. The authors found that SES negatively moderated associations between maternal employment and student achievement. Specifically, the evidence showed that children from high-SES families suffered from less maternal attention, supervision, and resources and poorer non-maternal care arrangements when their mothers were working. Conversely, low-SES students benefited from increased income, physical resources, and learning opportunities with maternal employment.

The third set of reviews showed that compared to high-SES peers, low-SES students benefited more from educational processes and interventions. For example, Mehana and Reynolds’(2004) meta-analysis involving 26 studies found that the association between students’ school mobility and their achievement (in reading and mathematics) was more negative for low-income (versus high-income) elementary school students. This finding was possibly due to instructional disruptions, discontinuities in relationships, and economic hardship, thereby highlighting the importance of school continuity as a necessary factor for low-SES students’ learning. In another review by Machin et al. (2013) on the effectiveness and value for money of different programs and policies in the UK, results showed that there were large and persistent differences in educational attainment between students from different SES families across grade levels, and that able students from low-SES families benefited from more targeted spending policies. These policies included increasing diversity in different types of schools accessible to low-SES students, increasing school resources via setting aside larger school expenditure to support low-SES student learning, and implementing literacy and numeracy programs for low-SES students. de Boer et al. (2018) meta-analyzed findings on the effectiveness of 48 metacognitive strategy instruction interventions and found that compared to ‘average students’ (i.e., students from middle-SES families and without special educational needs), low-SES students had the most long-term learning benefits from these interventions. In contrast to these reviews, Nelson and McMaster’s (2019) meta-analysis of 34 studies found that compared to ‘typically achieving students’, low-SES young children who were at risk for mathematics difficulty benefited less from early numeracy interventions. This finding may be due to the early nature of the interventions which target low-SES young children who are less prepared to benefit from these interventions.

The findings on how students from different SES families are influenced by different student, parental, school, and educational processes and interventions can be understood from Hanushek’s (1992) threshold theory highlighting that students (e.g., low-SES students) need a minimum threshold of resources or opportunities for learning. These resources and opportunities may be unavailable from families but are more easily accessed from schools or interventions. Specifically, compared to high-SES peers, low-SES students may be unable to benefit from personal and parental resources needed for their learning (Hansford & Hattie, 1982; Parker et al., 2020; Pinquart & Ebeling, 2020; Tan et al., 2020). However, they are able to benefit from ‘compensatory’ resources from having a stable school environment (Mehana & Reynolds, 2004) and educational interventions (de Boer et al., 2018; Machin et al., 2013).

Moderators of SES Influence in Student Learning

Apart from SES exerting a moderating role, the umbrella review also finds evidence of other variables moderating the SES influence on student learning (Table 3). These variables pertained to student demographic and neighborhood characteristics, types of learning outcomes, national socioeconomic development, age/grade levels, time, and types of indicators used to measure SES.

SES, Student Demographics, and Neighborhoods

There are numerous reviews that alluded to intersectional effects involving SES and other variables such as students’ gender, race/ethnicity, immigrant status, and neighborhoods for student learning. These reviews can be divided into two broad groups. The first group of reviews examined SES, gender, and ethnicity (Kim et al., 2019; Richardson et al., 2020). For example, compared to boys, girls were more adversely affected by low SES (Kim et al., 2019). Lastly, Richardson et al. (2020) reported evidence of persisting inequalities (since 2008) in the participation and academic attainment in UK higher education due to the intersectional influence of gender, SES, and ethnicity.

The second group of reviews examined SES and variables including race/ethnicity, immigrant status, and/or neighborhoods (Banerjee, 2016; Chang & Shih, 2023; Fleming & Malone, 1983; Harwell et al., 2017; Hunt & Seiver, 2018; Kaya & Selvitopu, 2023; Lotkowski et al., 2004; Mishra, 2020; Wang et al., 2023). The evidence indicated that these variables could either have cumulative or compensatory effects on student learning.

Cumulative Effects

Lotkowski et al. (2004) found that low-SES students, who might also be racial/ethnic minorities or immigrants or who lived in poor neighborhoods, often lacked access to quality education, financial aid, and academic and social support. These disadvantages impacted the students’ academic preparation, motivation, and socialization in colleges, thereby impacting the students’ learning outcomes. Hunt and Seiver (2018) concluded that SES, race/ethnicity, and immigration status combined to create multiple social class identities that students negotiated with their schools and influenced students’ access to educational resources, opportunities, and expectations. For example, low-SES, minority students from challenging neighborhoods might face immense difficulties in their learning for reasons related to discrimination, cultural values, parental involvement, school quality, and teacher expectations (Banerjee, 2016). Students from immigrant families faced additional challenges in their learning because their parents might not value education in the host country and their families might be more focused on addressing basic survival needs (Banerjee, 2016). Other reviews found that SES effects were stronger for (a) some racial/ethnic groups (e.g., Black, Asian-American; Chang & Shih, 2023; Fleming & Malone, 1983); (b) students in urban schools possibly due to neighborhood poverty, segregation, and lack of social capital (Harwell et al., 2017) or schools characterized by peer delinquency and racial discrimination (Chang & Shih, 2023); and (c) immigrant students because of acculturation issues, less access to resources, and greater exposure to neighborhood risks (Chang & Shih, 2023; Kaya & Selvitopu, 2023).

Compensatory Effects

Many reviews identified familial or community resources as having compensatory effects for disadvantages due to low SES, racial/ethnic minority status, immigrant status, or living in poor neighborhoods (Banerjee, 2016; Mishra, 2020). The familial resources included high levels of parental academic expectations (Kaya & Selvitopu, 2023) while the community resources included high levels of educational aspirations and expectations (Chang & Shih, 2023), information-related social capital, and social support (Mishra, 2020).

Societal Contexts Moderating SES Influence

Indicators used in reviews to measure societal contexts included GDP per capita, GINI coefficient, net enrollment ratio, duration of compulsory education, Education Index (average adult years of schooling and expected years of schooling for children), Human Development Index (measuring life expectancy, education, and per capita income), horizontal-individualistic/vertical-collectivist cultures, and Confucian heritage culture (Ciftci & Melis Cin, 2017; Kim, 2019; Liu et al., 2022; Nunes et al., 2022). However, a comparison of effect sizes reported in meta-analyses examining samples at different stages of their economic development or in specific countries indicates that SES effect sizes in economically developed countries were generally larger than those in less economically developed countries. For example, SES-achievement effect sizes ranged from r’s = 0.20 to 0.30 for US, Canadian, and English samples (Fleming & Malone, 1983; Harwell et al., 2017; White, 1982) as compared to r’s = 0.12 and 0.18 for student achievement and attainment respectively in developing countries (Kim et al., 2019; Selvitopu & Kaya, 2021). Kim (2019) attributed the small SES-achievement effect size in East Asian countries/regions to Confucian culture emphasizing filial piety and lifelong learning, parental involvement, shadow education, standardized and differentiated education systems, and high levels of teacher quality. Liu et al. (2020) reported decreasing SES-achievement effect sizes in China in the past decades and attributed the decline to socioeconomic changes, educational expansion, and equalizing governmental policies in the country.

Types of SES Indicators Moderating SES Influence

There were eight reviews (meta-analyses) that examined how SES effects varied with the use of different SES indicators (Harwell et al., 2017; Kaya & Selvitopu, 2023; Kim et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2022; Selvitopu & Kaya, 2021; Sirin, 2005; Tan et al., 2019). Results (Table 4) of meta-regression (k = 39) show that SES effect sizes for parental occupational status (β = -0.01, p = 0.86), family income (β = -0.01, p = 0.85), and home resources (β = 0.02, p = 0.58) were not significantly different from that for parental education (reference category).

Types of Learning Outcomes Moderating SES Influence

There were eight reviews (meta-analyses) that examined how types of learning outcomes moderated SES influence on student learning (Ciftci & Melis Cin, 2017; Fleming & Malone, 1983; Harwell et al., 2017; Kim et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2022; Selvitopu & Kaya, 2021; Sirin, 2005). Results (Table 4) of meta-regression (k = 23) show that there was no significant difference in SES effect sizes for student achievement in languages and STEM subjects (β = -0.00, p = 0.93; STEM subjects being the reference category).

SES Effects for Different Students’ Grade Levels

There were nine reviews (meta-analyses) that examined SES effects for different students’ grade levels (Ciftci & Melis Cin, 2017; Fleming & Malone, 1983; Goldberg et al., 2008; Harwell et al., 2017; Kim et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2022; Selvitopu & Kaya, 2021; Sirin, 2005). Results (Table 4) of meta-regression (k = 34) show that SES effects were larger for university students (β = 0.27, p < 0.05) as compared to kindergarten-elementary school students (reference category). However, these results must be interpreted with caution as there were only two effect sizes for university students. In contrast, there were no significant differences in SES effects for secondary school (β = 0.02, p = 0.74) or high school (β = -0.01, p = 0.94) students when compared to K-elementary school students. In addition to these reviews, Tan et al. (2019) argued that students’ grade levels could moderate SES effects because of the alignment of cultural capital with the doxa associated with different grade levels and students’ developmental needs. Their meta-analysis of 105 studies found that associations of different indicators of SES, conceptualized in terms of cultural capital, with student achievement varied with students’ educational stages.

SES Effects Across Time

There are three meta-analyses with sufficient effect size data on SES effects across time for synthesis (Ciftci et al., 2017; Harwell et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2022). Results (Table 4) of meta-regression show that the association between SES and students’ learning outcomes increased in the decade 1950 to 1959 when compared to that before 1950 (β = 0.17, p < 0.05). In contrast, the SES-outcomes associations for 1960 to 2000s were not significantly different from when compared to that before 1950. However, these results have to be read with caution given that there was only one effect size for each decade before 1990 (period before 1950, 1950 to 1959, 1960 to 1969, 1970 to 1979, 1980 to 1989); there were more effect sizes for 1990 to 1999 (k = 3) and for 2000 to 2021 (k = 8).

Discussion

Toward a More Comprehensive Conceptualization and Measurement of SES

The different shifts in the conceptualization of SES have the potential to enhance our understanding of the construct. Specifically, the inclusion of subjective indicators (complementing commonly used objective indicators) acknowledges the importance of self-appraisals in SES; i.e., one’s SES is as much what socioeconomic resources we have as it is who we think we are. The consideration of collectivity (in addition to individual attributes) in the conceptualization of SES implies that SES is only meaningful within the context in which it is measured, thus rendering difficulties for comparisons across different contexts. The conceptualization of SES as familial capital, instead of access to resources per se, needed for student learning reflects the increasing expectations and resource demands for students to excel academically. These expectations and demands are consistent with the Heyneman-Loxley Effect (Heyneman, 2015) which postulates that as countries develop economically, schools are less able to compensate for familial advantages, so families have to play a larger role in student learning. The call for a more diverse, asset-based perspective in the conceptualization of SES contends that students (especially from low-SES families) can have funds of knowledge from their families and communities that may differ from those found in high-SES families, that they can have different definitions of success in learning, and that these funds of knowledge can contribute to their learning (Moll et al., 1992).

With the emerging realization of the conceptual complexity in SES, informed by these shifts discussed above, researchers need to make important decisions when measuring the construct. Some of these decisions include the use of (a) one or more indices and (b) reflective or formative strategies to measure SES; (c) determining poverty thresholds in a society; and (d) meaningful comparisons of SES levels across societies.

Ecological Perspective of SES

The umbrella review suggests the importance of understanding SES from an ecological perspective to incorporate the various processes that mediate the SES influence on student learning, relationships between different variables and student learning that are moderated by SES, and contextual variables that moderate the SES influence on student learning. The many processes were related to students, home, teachers, and schools that past reviews have examined to explain the influence of SES on student learning can be understood from various theoretical perspectives (Bandura, 1986; Conger, 2005; Conger & Donnellan, 2007; Downey et al., 2004). SES may moderate relationships between many variables (student characteristics, parental influences, school processes, and the effectiveness of interventions) and student learning because of the minimum threshold of resources or opportunities that students need for learning (Hanushek, 1992). The moderating influence of SES in student learning and the identification of different variables (types of learning outcomes, national socioeconomic development, age/grade levels, time, types of SES indicators) that moderate SES influence on student learning allude to the contextual nature of SES. Indeed, SES appears to operate as a ‘catch-all’ variable as Jeynes (2002) has described. The implication is that researchers should consider and perhaps account for, SES influences at different levels (e.g., student, school, community) in their examination of student learning.

Large Student SES Effects in Educational Context

Notwithstanding the myriad ways in which SES can influence student learning (affecting student learning via different mediating processes and by moderating the impact of different variables on student learning), it is important to note the effect sizes of student SES in student learning. To reiterate, the second-order meta-analysis involving 15 meta-analyses yielded a SES effect size of r = 0.22 for student learning. This effect size may be regarded as being small when evaluated using the more conventional Cohen’s (1992) benchmarks that do not focus on educational interventions.

It may be more meaningful to understand the true influence of SES in three ways. First, the effect size has to be evaluated using benchmarks informed by educational research (Bloom et al., 2008; Kraft, 2020). Indeed, an effect size of r = 0.22 is deemed to be large in magnitude according to Kraft’s (2020) rules of thumb for educational research (r < 0.02 for small, 0.02 ≤ r < 0.10 for medium, r ≥ 0.10 for large effect sizes). Second, we can translate the SES effect size to improvements in students’ percentile points in achievement tests. In the context of our meta-analytic results (r = 0.22), a student with a SES score that is 1 standard deviation above the mean will likely score an average of 0.451 standard deviations more in an achievement test when compared to another student with a mean SES score (using Borenstein et al.’s (2009) formula converting from Pearson’s r to Cohen’s d). This difference in achievement translates to 16.69 percentile points (using von Hippel’s (2024) formula) – a substantial achievement difference. Third, we can compare the effect size with expected students’ annual achievement gains (Bloom et al., 2008). 0.451 of standard deviations is almost half of the expected annual achievement gains for students in early grades such as kindergarten to lower elementary school (e.g., 1 standard deviation) and more than twice that of the expected annual achievement gains of high school students (e.g., 0.20 or less standard deviations) (Bloom et al., 2008). The three approaches to interpreting our effect size indicate that SES has a large effect with substantial implications for student learning.

Having said that, the umbrella review finds evidence for the intersectional effects among SES and other student demographics such as their gender, race/ethnicity, immigrant status, age, grade levels, and even neighborhood characteristics. This intersectionality raises the question of confounding effects when we measure SES influence on student learning, thereby implying the need for researchers to control for these student demographics. It also means that the true SES effect on student learning may be smaller if we control for these demographic variables.

Asset-based Perspective of SES

Another finding from the umbrella review is that low-SES students appear to benefit from different policy interventions. Therefore, there is potential for low-SES students to achieve academic success and subsequently enjoy social mobility when they are given appropriate resources and support. This finding challenges the cultural deficit model where schools are blamed for contributing to low-SES students’ academic under-performance (Hunt & Seiver, 2018). To illustrate, Hunt and Seiver (2018) challenged deficit discourses about low-SES students. They discussed how educators’ class-based assumptions, high-stakes assessment practices, and class-biased curriculum sustained and reproduced these discourses in schools, and how students who adopted hybrid class identities, resisted deficit discourses, and questioned issues of income inequality could disrupt social reproduction.

Having said that, the caveat is whether low-SES parents can be persuaded to be engaged in interventions designed to help their children. The asset-based perspective (Garoutte & McCarthy-Gilmore, 2014; Missingham, 2017) inspires hope for developing academically resilient students. Academic resilience refers to ‘the heightened likelihood of success in school and other life accomplishments, despite environmental adversities brought about by early traits, conditions and experiences’ (Wang et al., 1994, p. 46). Rudd et al. (2021) found that students’ academic resilience could be measured using a threshold of achievement or resilience residuals. In terms of achievement thresholds, low-SES students were classified as being resilient if they achieved a specific achievement level or scored within a top specific percentage of the achievement distribution. Researchers employing resilience residuals classified students as resilient if the students performed better than expected (e.g., students having a specific achievement level after accounting for their low SES). Watkins (2019) identified student, parent, familial, school, and community factors that enabled parental socialization practices to develop academic resilience in low-income Black elementary school students, thereby improving the latter’s academic achievement.

Understanding SES in Context

The findings that SES can moderate relationships between different variables and student learning and that different variables can moderate the SES influence on student learning underscore the importance of examining SES in context. In this regard, an important question is whether socioeconomic inequality (a contextual condition) is improving or worsening over time and across countries/regions. Results from the umbrella review found mixed results for SES effects across time. Specifically, four reviews (Ciftci & Melis Cin, 2017; Harwell et al., 2017; Kim, 2019; Selvitopu & Kaya, 2021) reported strengthening SES-achievement effect sizes in the US and other societies over time. This pattern of results is consistent with those reported in Chmielewski’s (2017) analysis of 51 years of data (1964–2015) from 30 international large-scale assessments involving about 5.8 million students from 100 countries. Chmielewski (2017) found that SES achievement gaps had increased, presumably due in part to expanding school access and declining fertility.

In contrast to Harwell et al. (2017) and Ciftci and Melis Cin (2017), Liu et al. (2020) and White (1982) reported weakening SES-achievement effect sizes in China and across different countries respectively over time. These results are consistent with those reported by Hashim et al. (2023) who examined the impact of rising income inequality and income-based residential segregation on income-based achievement gaps in the US. Hashim et al. (2023) found that students’ mathematics achievement levels rose at all income levels and income-based achievement gaps for fourth and eighth graders decreased between 1992 and 2015.

Lastly, Early et al.’s (2020) findings of stable SES-achievement effects in the UK mirror those reported by Hanushek et al. (2020). Specifically, Hanushek et al. (2020) examined long-term trends (1954–2001) in the SES-achievement gaps in the US using data from the National Assessment of Educational Progress, Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study, and PISA and found that achievement gaps between the top and bottom 25% of the SES distribution had remained consistent, despite increasing students’ achievement levels at age 14.

As for the pattern of SES effects across countries/regions, results showed that SES effects were generally stronger in developed (vis-à-vis developing) countries, thereby alluding to the Heyneman-Loxley Effect (Heyneman, 2015). These results challenge the assumption that there will be less social reproduction with the massification of education in developed societies.

Limitations

As with all other research, results from the umbrella review should be read with a few limitations in mind. First, the umbrella review includes reviews that are indexed in nine key computer databases and employs a complementary search of relevant reviews. However, there may still be reviews that are not identified, especially those that are not written in English. Second, the umbrella review synthesizes findings from past review instead of primary studies. Lastly, it is unable to reconcile differences in some findings reported (e.g., processes mediating the SES influence, SES moderating relationships between different variables and students’ learning outcomes, and the trajectory of SES effects over time).

Conclusion

The umbrella review elucidates subtle shifts in the conceptualization of SES, identifies measurement issues plaguing the field, determines the SES effect size in student learning, and synthesizes the literature on mediators and moderators implicated in the relationship between SES and student learning. It makes three contributions to the literature (Table 5). First, the umbrella review underscores the need to expand the conceptualization of SES from being an objective and individual attribute that focuses on hierarchical differences in access to resources to a more comprehensive construct incorporating (a) objective and subjective evaluations of (b) individual and collective SES attributes; (c) emphasizing students’ mobilization of capital; and (d) adopting a more diverse, asset-based perspective of SES.

Second, the umbrella review provides a nuanced evaluation of the influence of SES in student learning. On the one hand, it yields a mean SES effect size of r = 0.22 (from a second-order three-level meta-analysis of 15 meta-analyses) that is deemed to be large with reference to educational benchmarks, expected students’ achievement gains, and percentile points in achievement tests. On the other hand, SES effects may suffer from confounding with other student demographics (gender, race/ethnicity, immigrant status, age, grade levels, neighborhood characteristics), so it is difficult to disentangle the true SES effects from those associated with other student characteristics.

Third, the umbrella review unravels (a) different ways in which SES influences student learning and moderates the influence of many variables on student learning and (b) different variables which moderate the SES influence on student learning, thereby suggesting that we need to understand SES from an ecological perspective.

Policy Implications

Findings from the umbrella review have important implications for policies aimed at improving low-SES students’ learning outcomes. Specifically, four principles can be distilled from these findings to inform the development of these policies. First, the ecological perspective of SES in student learning implies that such policies need to avoid a one-size-fits-all approach (Richardson et al., 2020). Instead, policy design, implementation, and evaluation should comprehensively address multiple factors (family school, community) influencing student learning (Banerjee, 2016; Waithaka, 2014; Wang et al., 2023), recognize the interactions among SES, race/ethnicity, immigration status, and neighborhood characteristics (Fleming & Malone, 1983), and cater to different domains of student wellbeing (academic learning, health, safety, socioemotional development) (Harwell, et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2023). Policymakers also need to collaborate with different levels of government and multiple stakeholders (non-government organizations, civil society, families, school leaders and teachers and communities) (Banerjee, 2016; Fleming & Marlone, 1983; Harwell et al., 2017; Kaya & Selvitopu, 2023; Richardson et al., 2020; Waithaka, 2014). For example, parents and communities can be involved in the development, implementation, and evaluation of policies (Kaya & Selvitopu, 2023). They should also enhance the social capital of disadvantaged students, such as increasing their access to educational information, guidance, and resources and to social networks (e.g., peer groups, faculty mentors, and learning communities) (Mishra, 2020).

The second principle stems from the finding that low-SES students’ learning outcomes can benefit from educational policies and interventions (Machin et al., 2013), so policies should enhance disadvantaged students’ access to educational opportunities and resources. For example, the policies can involve the expansion of early childhood education, provision of scholarship and financial aid, promotion of school choice and diversity, improvement of student–teacher ratio, de-tracking, provision of resources to school districts serving these students, and greater access to advanced courses and college education (Banejee, 2016; Fleming & Marlone, 1983; Harwell et al., 2017; Hunt & Seiver, 2018; Lotkowski et al., 2004; Mishra, 2020; Richardson et al., 2020; Waithaka, 2014; Wang et al., 2023). The enhanced access to educational opportunities and resources has to be matched by a leveling up of schools’ quality. For example, schools serving disadvantaged students need to be led by effective leaders and staffed by certified teachers who undergo continuous professional development, have high expectations for student learning, and implement effective curriculum and pedagogy (Fleming & Marlone, 1983; Harwell et al., 2017; Kaya & Selvitopu, 2023).

The two principles discussed above address the disadvantages that students face due to their economic deprivation (e.g., low-SES families, poor neighborhoods). However, effective policies must also address sociocultural aspects of disadvantage compromising student learning (e.g., related to racial/ethnic minority, immigrant status). The next two principles (i.e., third and fourth) focus on these aspects. The third principle is that policies should affirm the strengths (e.g., agency, resilience, creativity, cultural knowledge, community involvement) that disadvantaged students bring to their learning (Fleming & Malone, 1983; Harwell et al., 2017; Richardson et al., 2020; Waithaka, 2014). This principle is informed by the call for an asset-based perspective of SES (Long & Renbarger, 2023) and intersectional findings on the influence of SES with other variables on student learning (Banerjee, 2016; Chang & Shih, 2023; Fleming & Malone, 1983; Harwell et al., 2017; Hunt & Seiver, 2018; Kaya & Selvitopu, 2023; Lotkowski et al., 2004; Mishra, 2020; Wang et al., 2023). Policymakers should acknowledge that disadvantaged students are not homogenous and address the latter’s specific needs (Chang & Shih, 2023; Harwell et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2023). For example, affirmative policies on college admission and retention may benefit some groups of low-achieving, low-SES (e.g., Southeast Asian immigrant students) but disadvantage high-achieving East Asian–American students (Chang & Shih, 2023). Policies should include developing a culture of respect and dialogue among school leaders, teachers, parents, and students. Schools can cultivate safe spaces for sharing stories, promote multicultural programs and teaching social justice, implement anti-bullying programs, support students at risk of dropping out, and enhance school-family collaboration (Hunt & Seiver, 2018; Kaya & Selvitopu, 2023; Lotkowski et al., 2004; Mishra, 2020). Teachers need to have diverse backgrounds, appreciate diverse cultures, serve as role models for students, and be trained to engage with diversity issues in classrooms (Hunt & Seiver, 2018; Kaya & Selvitopu, 2023).

Lastly, in view of the findings indicating the persistent influence of SES on student learning, policies should address structural and systemic inequalities related to poverty, classism, and segregation (Hunt & Seiver, 2018; Mishra, 2020) by cultivating equitable and inclusive assessment and accountability education systems (Harwell et al., 2017); this is the fourth principle. These systems are exemplified by the use of multiple measures of student learning, culturally responsive pedagogies and curriculum, parental involvement, school desegregation, and contextualized school admissions (Hunt & Seiver, 2018; Fleming & Marlone, 1983; Richardson et al., 2020; Waithaka, 2014). The aim of the policies should be social transformation instead of merely improving access or achievement of disadvantaged students (Richardson et al., 2020).

Future Research

There are three suggestions for future research to unravel the influence of SES on student learning. First, future research can examine the influence of SES on student learning in evolving digital learning contexts. For example, the COVID-19 pandemic has eventuated in a New Normal where student learning shifts from face-to-face, school-based instruction to a more hybridized mode of learning comprising home-based, online learning and face-to-face lessons in school. Parenting may correspondingly assume a digital character (i.e., digital parenting) in addition to traditional home- and school-based parental involvement (Tan et al., 2022). These developments portend the threat of digital divides in student learning where low-SES students may be disadvantaged in their learning because of limited access to and inappropriate use of digital technology (Selwyn, 2004; Tan & Hew, 2019). Indeed, Sun and Metros’ (2011) concluded from their review of the literature on digital divides that SES and social capital influenced students’ access to institutional resources and opportunities to use technology in their learning.