Abstract

To address the seven guiding questions posed for authors of articles in this special issue, we begin by discussing the development (in the late 1970s-early 1980s) of Eccles’ expectancy-value theory of achievement choice (EEVT), a theory developed to explain the cultural phenomenon of why girls were less likely to participate in STEM courses and careers. We then discuss how we tested key predictions from the theory, notably how expectancies and values relate to achievement choices and performance and how socialization practices at home and in school influence them. Next, we discuss three main refinements: addressing developmental aspects of the theory, refining construct definitions, and renaming the theory situated expectancy value theory. We discuss reasons for that change, and their implications. To illustrate the theory’s practicality, we discuss intervention projects based in the model, and what next steps should be in SEVT-based intervention research. We close with suggestions for future research, emphasizing attaining consensus on how to measure the central constructs, expanding the model to capture better motivation of diverse groups, and the challenges of testing the increasingly complex predictions stemming from the model. Throughout the manuscript, we make suggestions for early career researchers to provide guidance for their own development of theories.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

WeFootnote 1 are pleased to have the opportunity to discuss the development of what is now called situated expectancy-value theory (SEVT). We trace the early development of the model from Parsons et al.’s (1976) early work, discuss some of the studies testing different aspects of the model, describe theoretical refinements (notably the renaming to situated expectancy-value theory), and close with suggestions for future research. We organize our article around the seven questions Editor Greene asked us to answer.

What Inspired the Theory and What Observations and Phenomena Were You Trying to Describe, Understand, and/or Explain

During graduate school, two major forces influenced or inspired Eccles’ (then Parsons’) growing interest in both gender and individual differences in achievement motivation: (1) the excitement at UCLA in social cognitive influences on behavior, particularly those linked to attribution theory and the role of human agency in human development, and (2) the women’s movement. These two influences sparked Parsons’ interest in studying and understanding gendered life achievement-related choices. Working together with a terrific set of women graduate colleagues, Parsons coedited a special issue of the Journal of Social Issues entitled Sex roles: Persistence and Change (Ruble et al., 1976) that provided a new look at differences in women and men’s motivation and choice of different activities/occupations to pursue.

Developing the Theory

Parsons was Bernard Weiner’s Ph. D. student in the social psychology department at UCLA and also worked primarily with other social psychology students and faculty; thus, she was well versed in the field of social psychology. Weiner was Jack Atkinson’s student at the University of Michigan and so his research was on human motivation. Thus, Parsons had many opportunities to discuss the motivational theories of Atkinson, McClelland, and Weiner as well as the related work by social and developmental psychologist like Bandura, Kelley, and Maccoby. Interestingly, although Weiner was Atkinson’s student, he had gotten disillusioned with aspects of Atkinson’s (1957) theory, and the use of the thematic apperception test (TAT) as a primary measuring instrument (Weiner, personal communication, May 2019). He became interested in attribution theory and was developing his own version of it while Parsons was at UCLA. This sparked her interest in cognitive aspects of motivation, such as attributions and ability-expectancy beliefs (e.g., Parsons & Ruble, 1977), both of which are included in the model.

Parsons began to develop an expectancy-value theory based theory of choice during these projects in conversation with her social psychology peers. They (Parsons et al., 1976) published the first version of what was to become the model in the 1976 Journal of Social Issues mentioned above. Their initial version of the model had four boxes: cultural norms and expectations, current situational factors (e.g., discrimination), socialization in home and schools, and personal attitudes and values, and behaviors. Their focus was on gender differences in college women, so sample constructs in this preliminary model referred primarily to gender.

In 1973, Parsons moved to Smith College as a developmental psychology faculty member; this of course led her to be well-versed in developmental theories and research on motivation and other subjects. In her thinking on motivation, she was particularly influenced by Battle’s (1965, 1966) and the Crandall’s’ (Crandall, 1969; Crandall et al., 1965) work on attainment value in relation to task choice. As a developmental psychologist interested in the first two decades of life, Parsons became increasingly interested in school and schooling and their differential effects on boys and girls. This brought her in contact with the field of educational psychology.

During her time at Smith, Parsons began having many conversations with students, notably Susan Goff, on the broader topic of incentive values and their impact on achievement choices. Parsons and Goff (1980) is the publication resulting from these conversations. This chapter was foundational for the development what would become the full model. Parsons and Goff critiqued Atkinson’s (1957) theory (arguably the dominant motivation theory of the time) in two primary ways. First, they noted that Atkinson’s model had not been particularly successful in predicting women’s outcomes, indicating that some re-conceptualization was in order. Second, they critiqued and expanded Atkinson’s view of incentive value. In the mathematical formulation of his model of resultant achievement motivation, Atkinson defined incentive value as 1–Ps (probability or expectancy for success). Parsons and Goff stated that this essentially eliminated incentive value as its own construct in the model and consequently researchers focused primarily on expectancies rather than value (see Wigfield & Eccles, 1992, for full discussion of this issue). Rather than simply being an inverse of Ps, Parsons and Goff proposed that task or incentive value has different components and is a distinct from expectancies/probability of success. They provided the first discussion of different potential components of task value, mentioning attainment value, utility value, and whether rewards were seen as intrinsic or extrinsic. They also mentioned costs, particularly with respect to women’s choices regarding family and career. They also made the first mention of the idea that people have a hierarchy of values and that these can differ across individuals and groups, such as men and women.

Three and one-half years later, Eccles moved to The University of Michigan and began to elaborate the model with her graduate students. They did so to provide the theoretical rationale for a study of why females are less likely to go into mathematics than males; as discussed later, this study was funded by the National Institute of Education. In 1983, Parsons (now Eccles-Parsons) published the first chapter devoted to the model; her graduate students were co-authors Adler, Futterman, Goff, Kaczala, Meece, and Midgley. At that time, they referred to it as “a general model of achievement choice… which is most directly influenced by theories in which the constructs of expectancies and values are prominent” (p. 76). In later publications, Eccles began calling the model the Eccles et al. expectancy-value theory (EEVT; for example, see Eccles, 2005).

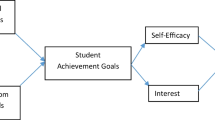

The model builds on Atkinson’s (1957) earlier work with its focus on expectancies and values. However, building on Parsons and Goff’s (1980) analysis, Eccles-Parsons et al.’s (1983) chapter defined the expectancy for success and task value constructs in much richer ways than Atkinson did, and linked them to a much broader array of more distal psychological, social, and cultural influences grounded in both developmental and feminist psychology. Their initial goal was to identify the major categories of social and psychological influences on people’s achievement-related behavioral choices that could aggregate across individuals to yield mean level differences at the population level in choices of females and males. Each of the boxes in the model in Fig. 1 stands for one major category of influence. They included specific examples of each category within each box. These examples were never intended to be exhaustive of the range of constructs that fit within each box, in part because this chapter focused heavily on gender differences. Second, they set out to specify the most probable connections between these categories as mechanisms for how socialization and enactment play out in individuals’ lives both over time and at each specific moment of action. Interestingly, given its impact in educational psychology, its roots and many of its early publications are in social, motivational, and developmental psychology—not educational psychology. The impact in educational psychology likely has occurred because of the focus on children and adolescents’ choices regarding different academic tasks to pursue, and the impact of schooling on the development of students’ expectancies and values.

Eccles-Parsons et al. (1983) divided their presentation of the model in two parts, the psychological component of the model and the socialization component. We discuss each in turn. Because the key belief and value constructs have been defined in numerous other publications, we define them briefly here. Figure 1 presents the current version of the model.

Psychological Component of the Model (Agency)

Eccles-Parsons et al. (1983) postulated that both achievement-related performance and task choice were influenced most directly and immediately by individuals’ relative expectations for success at and the subjective task value (STV) of the action chosen compared to expectations for success at and the STV of the readily available alternatives. They assumed that both expectancies and STVs themselves were influenced by individuals’ task-specific beliefs such as their self-concepts of various abilities, and their goals and self-schema, along with their affective memories for different achievement-related activities. Furthermore, they assumed that these beliefs, goals, and affective memories had been formed developmentally via individuals’ perceptions of other peoples’ attitudes and expectations for them, and by their own interpretations of their previous achievement outcomes. As discussed in more detail below, they predicted that these perceptions and interpretations had been influenced by a broad array of social and cultural factors, including socializers’ (especially parents and teachers) beliefs and behaviors, children’s prior achievement experiences and aptitudes, and the cultural milieu in which they lived.

Defining Performance Expectancies, Self-Concept of Abilities, and Subjective Task Values

Beginning with Eccles-Parsons et al. (1983) and moving to our own writings (e.g., Eccles & Wigfield, 1985, 2023; Wigfield & Eccles, 2000, 2020), we define expectancies for success as individuals’ estimates of how well they would do in the near or far future on any specific task or activity; for example, this or next year’s math class. In contrast, we define SCA as a more general stable estimate of one’s global but domain specific ability. In the model, Eccles-Parsons et al. postulated that task specific success expectations derived from the individuals’ domain specific SCAs. However, as measured, the items tend to factor together; we will use SCA to refer to both in the remainder of this article.

Eccles-Parsons et al. (1983) defined STVs with respect to the qualities of different achievement tasks and how those qualities might influence the individual’s desire to do the tasks (Eccles, 2005; Eccles-Parsons et al., 1983; Wigfield & Eccles, 1992). They proposed that one’s overall STV for any given activity or task is a function of four components: intrinsic value or enjoyment, utility value or usefulness of the task for other goals, attainment value, and perceived cost. As just noted, intrinsic value means finding a given task or activity enjoyable. Utility value, or usefulness, refers to how a task fits into an individual’s current or future plans, for instance, taking a math class to fulfill a requirement for a science degree. However, the activity also can reflect some important goals that the person holds quite deeply, such as attaining a certain occupation. Eccles-Parsons et al. (1983) defined attainment value as the importance of doing well on a given task. Over time, Eccles (2005, 2009) connected attainment value more and more closely to the individual’s personal and social identities, so it became a broader construct than the importance of a task.

Eccles-Parsons et al. (1983) described cost in terms of cost/benefit ratio for different activities. If an activity “costs” too much, the individual will not do it (see also Eccles, 2005). They described different kinds or types of costs: individuals’ perceptions of how much effort they would need to exert to complete a task and whether it is worth doing so (effort cost), how much engaging in one activity means that other valued activities cannot be done (opportunity cost), and the emotional or psychological costs of pursuing the task, particularly the cost of failure (e.g., psychological cost). As discussed later, we and other researchers now have proposed other possible dimensions of cost.

We postulate that one’s overall STV for an activity is a function of a complex, not necessarily conscious, weighting scheme of the different aspects of task value just discussed. What is crucial in our view is that STV as a continuous higher order construct that could vary from very negative to very positive. Its level would derive from the algorithms used by the individual to aggregate across the multiple of more simple unidimensional constructs mentioned above.

Within Individual Influences on Expectancies, Ability Self-Concepts, and Subjective Task Values

The boxes in the middle of the model contain various psychological variables/constructs that impact individuals’ expectancies for success and STVs: for example, their goals and self-schemata, their perceptions of how hard the task or activity would be, their affect towards the activity based on previous experiences with similar activities, and their interpretations/understanding of how well they have been doing on the activity. Also critical are their understandings and interpretations of the messages they receive from different socializers. Eccles-Parsons et al. (1983) took these predictions from work in social psychology being done at the time regarding how perceptions and interpretations of experiences were the main pathways through which objective experiences in the real world influenced individuals’ beliefs and behaviors. As the field changed to emphasize the influences of culture, context, and the particular situations in which individuals find themselves, we have softened our stance on this point that it is primarily the individual as key.

Social Structure and Socialization Components of the Model

The left side of the model is focused on the social structure component of our agency and social structure general framework. Eccles-Parsons et al. (1983) originally limited this aspect of the model to two boxes, one specifying the larger cultural setting in which the individual is living (and emphasized gendered aspects of culture) and the other specifying the role of socializers. We now have elaborated what we think are the aspects of parents, teachers, and broader characteristics of school environment that impact expectancies and values; see Eccles (1993), Eccles and Wigfield (1985), Eccles et al. (1998), and Wigfield et al. (2006). Figure 2 illustrates such an elaboration regarding parental influences. Similarly, we characterize school influences as several different types of teacher in-class behaviors (e.g., differential use of praise and criticism across individuals and groups of individuals, classroom supportive climate, quality of teaching the subject matter, classroom support for student autonomy, and differential support for autonomy).

In the reviews of the original submission of our manuscript, one reviewer asked for our perspective on whether theories should be well-formed at the beginning (because of previous research and/or a well-defined problem space that allows for that) or built as the research progresses. The reviewer viewed EEVT as well-formed at the beginning, and then tested and tweaked, rather than being built along the way, a view with which we for the most part agree. Our answer to the question of which approach to take is that it is situated! With well-defined problem spaces and a reasonable amount of research, theories can be built from the start. In other circumstances, the theory can be built as one goes along, as much design-based research does. Another part of the answer to this question is that one’s approach depends on how one views science and scientific progress. This would be an intriguing topic for fuller consideration in another article. Even with what we consider to be a relatively “fully formed” theory, we hope this section makes clear that there was a “developmental process” over several years before Eccles-Parsons and colleagues presented the first full version of the model in 1983.

Did Findings Lead to Some Changes in the Theory? Or Did Unexpected Findings Lead to New Directions?

The first studyFootnote 2 testing certain predictions from the model was the NIE funded study mentioned earlier, that started in 1978. It was the first study of its kind conducted anywhere in the world, in that it used both survey and observational methods to study both social and psychological influences of gendered life choices and included students, parents, and teachers. As such it laid the groundwork for all subsequent research on the model.

We tested some key predictions from the model and explored many other questions. Regarding the proposed expectancy and value constructs themselves, Eccles and Wigfield (1995) demonstrated (using confirmatory factor analysis - CFA) that students’ expectancies for success factored separately from their subjective task values, providing support for the distinctions between the constructs. Students’ expectancies and values were positively correlated, suggesting that students value more the subjects at which they expect to do well and vice versa. The CFAs also showed that the three subjective task components measured in the study (interest, importance, and utility) each formed a separate factor. Thus, these components not only could be distinguished theoretically but also empirically. However, the items assessing expectancies for success and SCAs factored together, suggesting that although they can be distinguished theoretically, they are closely related empirically. Perhaps a more elaborate set of items would provide the differentiation.

We tested several predictions regarding expectancies, values, and different outcomes. Meece et al. (1990) examined the predictive links of students’ expectancies and STVs in math to their performance and intentions to continue taking math, looking at these relations over a 1-year period. They found that students’ expectancies for success were the strongest direct predictor of their subsequent math performance, and the importance they attached to math was the strongest direct predictor of their intentions to continue taking it in high school. Each had both direct and indirect effects on the outcome variables of performance and intentions.

Turning to gender differences, we will mention three key sets of findings. First, girls and boys themselves hold different views of their math, reading, and sports abilities that conform to American gender-role stereotypes and make different attributions for their performance that reinforce gendered stereotypes about abilities in these fields (Eccles et al., 1984; Eccles-Parsons et al., 1982c). Second, math teachers interacted differently with girls and boys despite quite similar performances by these two groups of students (Eccles-Parsons et al., 1982b; Heller & Parsons, 1981). For example, teachers called on boys more than girls, which reflected the fact that boys actually demanded more attention than the girls by raising their hands and shouting out answers. Third, parents provide their boy and girl children with different feedback regarding their math talents and performances (Eccles & Jacobs, 1986; Eccles-Parsons et al., 1982a; Jacobs & Eccles, 1986). For example, parents were more likely to attribute their son’s math success to talent and their daughters’ math success to hard work.

These results supported our hypotheses regarding the origins and enactments of gendered stereotypes about math, reading and sports abilities in the USA (see Eccles, 1987). Furthermore, our studies demonstrated the power of a wholistic, psychological, and sociocultural model for guiding a comprehensive investigation of questions around broad topics like why are their fewer females entering fields based in STEM than males?

Pursuing Explanations for Unexpected Findings

Wigfield joined the research group in 1981 as a postdoctoral fellow; he was particularly interested in the development of motivation. The research team at Michigan next conducted two large-scale longitudinal studies to get at how children’s motivational beliefs and values change over time and understand at least some of the factors in the home and school environments that contribute to those changes.

It is important to say at this juncture that developmental questions were not initially a major focus for the development of the EEVT model. Furthermore, no one had generated specific predictions about what the course of the development of motivational beliefs and values would be, or which factors at home and school would most influence the changes. The developmental studies came about, first, because of an unexpected finding in the NIE funded study, and second, because Eccles and Wigfield became increasingly interested in the question of when the key motivational beliefs and values proposed in the model emerged. Both studies are examples of how a large, overarching framework can lead to studies that were not necessarily a part of the original plan for the model. They also reflect the importance of a project director who always was interested in answering new questions, the presence of a new post doc who was eager to take the team in new research directions, and an immediate and quickly growing bond between Eccles and Wigfield.

One of the major unexpected findings in the NIE project was a general cross-sectional downward shift in students’ motivational beliefs related specifically to math between grades 5 and 9. When we investigated this decline more carefully, we found that the differences was quite marked between grades 6 and 7, exactly the time when the students in our study were making the transition to junior high school. At the same time, Simmons and Blyth (1987) were finding a similar negative shift in other indicators of adolescent well-being occurring in conjunction with the junior high school transition.

What explains these developmental differences? Many scholars would be tempted to attribute these declines loosely in terms of some biological aspects of pubertal development linked to either hormonal changes or brain development. In contrast, drawing on the work by Simmons and Blyth (1987) and the theoretical work by Higgins and Eccles-Parsons (1983), we predicted that these declines could result from systematic negative changes in processes linked to the shift in educational social experiences associated with the transition to junior high school. We also expected there to changes at the level of the classroom that could undermine the students’ academic motivation.

Given our central goal, we designed a study to gather within-classroom data two times each year on the same students (N = 3000) as they went through their last year in elementary school and then into and through their first year of junior high school. We chose this design because we wanted to be able to separate within and across year change in students’ expectancies, values, and other beliefs. As we had predicted, the strongest declines in students’ self-esteem and beliefs about ability/expectancies for success occurred between spring of the pre-transition year to fall of the post-transition year (Wigfield et al., 1991). Students “self-esteem recovered some during seventh grade but students” ability beliefs for math and English continued to decline, as did their liking of English and math. Boys reported higher self-esteem at each measurement point, and gender differences in beliefs about specific abilities followed gender stereotyping, just as we found in the NIE study.

To test our hypotheses regarding school level by classroom level by student level developmental processes, we assessed the extent to which changes in the students’ pre- and post-transition teachers’ beliefs explained the nature of the changes in the math motivational beliefs of our sample of students as they developed across these four waves of data. Some key findings were that junior high math teachers were more controlling, less trusting of their students, and used more social comparative grading strategies than did elementary school teachers. They were less likely to have confidence in their ability to teach all of their students and to be seen by their students as supportive and caring (Midgley et al., 1988, 1989a, b). In classrooms where these changes were strongest, it was more likely that students showed a decline in their math related expectancies for success, ability self-concepts, and subjective task values (Wigfield et al., 1991).

To explain these findings, Eccles and Midgley (1989) and Midgley et al. (1989a, b) proposed the notion of stage-environment fit as key to healthy development. Students’ emotional adjustment and motivational beliefs had been undermined by a developmentally inappropriate shift in the educational environments to which they were exposed. This new notion was not a change in EEVT per se but represented an extension of it into a new area. It is perhaps analogous to the notion of a “mini-theory” within the larger theory along the lines that Ryan and Deci (2017) discuss in self-determination theory.

In part, based on our results and other work by researchers such as Simmons and Blyth (1987), the Carnegie Council on Adolescent Development (1989) produced a report on middle grades education that recommended that the structure of traditional junior high schools (which essentially mimicked high school structure) be changed into what are now called middle schools. The new school structure, at its best, is designed to produce stage-environment fit rather than misfit with respect to the developmental needs of early adolescents and their school structures. The interested reader can learn more about this change in Eccles’ (1993) discussion of how middle schools and traditional junior high schools vary in their structure, organization, and approach to the education of early adolescents. This recommendation was followed in many districts throughout the USA.

When Do Expectancies and Values Emerge During Childhood? The Childhood and Beyond (CAB) Study

Given our new developmental focus, we next decided to look at the early emergence of the key motivational beliefs and values in the model, developmental changes in the associations among these constructs, and their predictive role in explaining both individual and groups differences in achievement in academic, sports, and instrumental music domains. In order to carry out these goals, we first needed to create good measures of our psychological constructs that were appropriate for students across the kindergarten through twelfth grade years of schooling, which was a daunting task. The project had a cohort-sequential design in which we started measuring children’s their expectancies and subjective task values in different activity domains, and a variety of other constructs yearly, starting when children were in first, second, and fourth grades. Ultimately, we measured these variables until the oldest cohort was in twelfth grade, and then followed a subset of the sample until they were in their early 30s, in order to obtain information about their career choices. The sample was 95% white.

The key findings of this study were (1) children’s SCAs and STVs were differentiated from each other in the first grade and become more strongly differentiated with age (Eccles et al., 1993); (2) children’s SCAs and STVs formed distinct factors in each domain. Thus, children did not have a general belief representing their expectancies, or values, across domain, but differentiated beliefs and subjective values in each domain. In contrast, children’s anxieties did not differentiate by domain, suggesting that anxiety about one’s performance in skill-based domains reflects a more general response than do ability SCAs and STVs; (3) the strength of the association of ability self-concepts and expectancies for success, although always positive, become much stronger over age, as do the associations between expectancies, ability self-concepts and various aspects of subjective task values; (4) regarding change over time, early articles (Jacobs et al., 2002; Wigfield et al., 1997) reported decreases in students’ beliefs and STVs in the different domains studied. More recently researchers report many different patterns of change in students’ SCAs and STVs (e.g., Archambault et al., 2010; Gaspard et al., 2020; Musu-Gillette et al., 2014); and (5) gender differences in children’s SCAs and STVS generally corresponded to gender role stereotypes. Interestingly, however, in math, the gender differences disappeared over time.

Turning to hypothesized predictive links of children’s expectancies/ability beliefs and subjective task values to performance and choice, both Musu-Gillette et al. (2014) and Gaspard et al. (2020) investigated the long-term linkages of children’s beliefs and subjective task values to their course enrollments, choices, and career choice. Both reported different trajectories of change in children’s SCAs and STVs from first through twelfth grade. They found that membership in a different trajectory, or class, predicted later course enrollments, aspirations for different careers, and career choices. For example, children in a class characterized by strong declines in beliefs and subjective values for math were much less likely to be in a math-related career than children with more positive math beliefs and values.

How do we explain these changes? One way is to look at how change in children’s SCAs, STVs, and activity engagement is predicted by parents’ beliefs. Utilizing the elaborate CAB data obtained from parents, Simpkins et al. (2015) found that parents can have strong influences on their children’s continuing engagement in different domains even when child competence and participation are controlled. They also found that children’s competence beliefs often predicted change in parents’ beliefs about their children’s abilities, indicating the complex bi-directional relations between parent and child beliefs.

With respect to theoretical “advances,” Wigfield (1994) presented a developmental analysis of the theory, based in part on the results from CAB and also from other work on the development of motivation extant in the literature. Wigfield suggested that the emergence of the different components of children’s STVs likely would be in the order of interest value first, followed by attainment value and utility value. As noted earlier, attainment value has ties to identity, which develops during early adolescence. Young children might have an understanding of some things being important to them, but the full meaning of attainment value as expressed in Eccles (2005, 2009) will emerge later in development. Similarly, understanding what skills will be useful to one later also takes some time to develop; it is unlikely that a 7-year-old will have a clear sense of which of the things she is learning ultimately will be useful to her later. Wigfield also proposed that both the relations between children’s SCAs and STVs, and their relations to outcomes, will become stronger over time, something that Wigfield et al.’s study (1997) demonstrated. They found that the correlations of children’s SCAs and STVs increased in strength across the childhood years, as did the relations between children’s belief and values and their teachers’ ratings of their performance. One way to visualize this is to think of the arrows in Figure 1 as being faint early in the school years, and gradually filling in over time.

To conclude this section, we built on some unexpected early findings regarding change over time in children’s SCAs and STVs to examine their development across the school years. This led us to consider the very early emergence of these beliefs and values, which in some ways can be considered to be addressing the question of when does the model and its predictive links emerge? Such questions were not necessarily there at the beginning when Eccles-Parsons et al. (1983) first posed the model, but became interesting due to early findings, and lead investigators’ curiosity regarding the early development of motivational beliefs and values. A lesson for early career researchers is that even when one is working within a particular and (if we can presume to say this) well-specified framework findings can be a surprise, and the addition of new members to a research team will result in different issues being addressed than might have been anticipated at the beginning. Both of these things make the research enterprise exciting rather than too cut and dried.

What Is the Current Status of the Theory? How Is It Similar and Different Than the Initial Theory You Created?

We will consider “status” in two ways. First is status in the sense of the “relative standing” of the theory. In that sense, we (immodestly) say that the theory remains one of the most prominent theories in the motivation field; evidence for this is its inclusion in both special issues of Contemporary Educational Psychology (one published in 2000, one in 2020) devoted to major motivation theories in educational psychology, and its inclusion in McInerney and colleagues edited volumes entitled “Big Theories of Motivation” (McInerney & Van Etten, 2004; Liem & McInerney, 2018). Eccles and Wigfield’s (2020) article on the change from expectancy value theory to situated expectancy value has been cited nearly 1400 times; Wigfield and Eccles’ article in the 2000 Contemporary Educational Psychology special issue over 10,000. We take this as evidence that the theory is still vibrant and provides theoretical framing for the work of variety of researchers from around the world.

However, in some comments on another article focused on the theory, a reader wondered about the continued viability of a 40 + -year-old model. To address this, Wigfield asked a non-random sample of junior colleagues why the theory still guided much research in the field (including their own). They mentioned a number of things about SEVT: (1) it is a clearly defined theory from which to draw testable research questions, (2) there are good measures available to assess the relevant constructs, (3) the emphasis on both the context/situation and the individual rather than one or the other, (4) the comprehensive nature of the theory that captures more than one piece of the motivation puzzle and connects many dots, and (5) easy to use and explain to educators; the terminology is accessible to those outside academia.

Turning to status in the sense of “current state “of the theory, several things have happened since Eccles-Parsons et al. (1983) first proposed the model. One is that some of the constructs have been reconceptualized and elaborated for theoretical and empirical reasons. We mention two examples from the right side of the model here, attainment value and cost, and two from the left side. As discussed earlier, Eccles (2005, 2009) increasingly has connected attainment value to individual’s developing identities. She has written in particular about the salience of tasks with respect to one’s gender identity, and also other central aspects of one’s identity. When activities mesh with one’s identity, then they are more likely to be pursued and incorporated into one’s broader sense of self. To date, this newer conceptualization of attainment value has not been addressed fully; we return to this point below.

Eccles-Parsons et al. (1983) proposed three dimensions of cost: effort cost, loss of valued alternatives, and psychological cost of failure. For many years, cost was neglected by researchers basing their work in EEVT; Flake et al. (2015) called it the “forgotten” component of expectancy-value theory. That began to change with Battle and Wigfield’s (2003) study of college students’ perceptions of the costs of graduate school, and then especially since 2014 or so. Researchers have developed new measures of cost for students in grades five through college (Flake et al., 2015; Gaspard et al., 2019; Perez et al., 2014), and proposed adding additional aspects of cost (see Wigfield et al., 2017, for a discussion of these possibilities as well as our own suggestions regarding the possible dimensions of cost). For example, Flake et al. distinguished effort cost related to the task and effort cost unrelated to the task (outside effort cost). They called psychological cost emotional cost. Gaspard et al. initially distinguished emotional cost from effort cost but due to their high correlation ultimately recommended combining them. More recently, Beymer et al. (2023) developed measures of both anticipated cost (students’ sense of how costly their classes were going to be) and experienced costs measured at the end of the semester. They found that those with higher anticipated cost tended to have higher experience cost. Interestingly, those with higher anticipated cost had better achievement outcomes. Song et al. (2023) examined the factor structure of emotional cost, psychological cost, and anxiety. They found that emotional and psychological costs factored separately, whereas emotional cost and anxiety often overlapped empirically. This left the researchers wondering how distinct the constructs are. Finally, Matthews and Wigfield (in press), in an article discussing ways to racialize aspects of SEVT, proposed that racialized opportunity cost (see Tabron & Venzant Chambers, 2019; Venzant Chambers, 2022) be added as a component of cost. It refers to students of color’s sense of what they must give up about themselves when attending primarily white schools. This new work has not been fully incorporated into the figure representing SEVT, in part because there is not yet consensus on what cost comprises. That is a task for future research.

Based on results showing that aspects of cost correlated more strongly with SCAs than it did with aspects of STV and also that the cost dimensions factored separately from the other aspects of value, Barron and Hulleman (2015) proposed that expectancy value theory be re-named expectancy value cost theory. In our own writings, we have argued that the evidence is not strong enough yet to add the C to EEVT (Eccles & Wigfield, 2020; Wigfield & Eccles, 2020). Space precludes a long discussion here, but to us the factor analytic evidence is not compelling because all the aspects of task value form separate factors. Research by Part et al. (2020) supports our view; their factor analyses of students’ responses to a questionnaire measuring college life science students’ expectancies, values, and cost perceptions revealed an overall task value with different components including cost. Muenks et al. (2023) measured college biochemistry students’ expectancies, values, and costs in a “high stakes” biochemistry course and found that models that subsumed cost under values and those that had cost as distinct from value both fit the data well provide some support for both views. Muenks et al. suggested that the results of different studies supporting cost as separate from value versus cost as part of task value might reflect differences in educational contexts; that is, they might reflect situational differences. Future research can continue to address this issue.

We mention two broad changes to the socialization side of the model. First, as noted earlier, we (and others) have written extensively about the particular kinds of experiences students have in school that can impact, either positively or negatively, their SCAs and STVs. These include different aspects of the quality of teacher-student relationships, grading practices, and school structural issues, among other things We have not systematically included these in our depiction of the model, that is something we are working on currently. With respect to parent socialization, Simpkins et al. (2015) findings supported some of the predictive links in the parent socialization model shown in Fig. 2 but not all of them; we are in the process of revising that figure as well to reflect these results (Eccles, Wigfield, & Simpkins, in preparation).

From EEVT to SEVT: Why the Change?

Year 2020 brought a major change to the theory, perhaps the most significant change made in the past 20 years. Eccles and Wigfield (2020) proposed changing the name from Eccles expectancy-value theory to situated expectancy-value theory. Why this change? There were several reasons. First, situative views of motivation that emphasize the importance and (in some cases) the primacy of the situation’ role on individuals’ in-the-moment motivations are increasingly prominent in the motivation field (see Nolen, 2020). In the model, we have always considered the situation’s impact on children’s developing motivation to be an important aspect of the model; indeed, even the “precursor” to the model in Parsons et al. (1976) includes the term “situational” in one of the boxes. We believe all aspects of the model are situative, even if the model in Fig. 1 does not fully capture that aspect of our work. For example, the right side of the model shows students’ expectancies and values predicting performance and choice. We assume (and actually always have assumed) that these decisions and the subsequent enactments are very situated. Each person will arrive at each decision point with their own set of available options that operate either in the moment or over longer time frames. They will only be familiar with a very limited subset of all possible behaviors and options. They will only have a small subset of the skills and resources that could be drawn on in enacting whatever decision they make. Both their own view and the view of those around them of what is going on and the available options will be limited. As a result, both their own hierarchy of SCAs and STVs and the hierarchies of those around them will be limited and very much tied to their current “situation.” So rather than being global and generic (which the representation in Fig. 1 can seem to be) people’s motivation beliefs, STVs, and decisions are situated and specific.

Having said that, it is important to acknowledge that in her commentary for the special issue of Contemporary Educational Psychology on major motivation theories, Nolen (2020) stated that situative approaches are based in different epistemological traditions than more psychologically based theories of motivation such as expectancy-value theory. They are rooted in Vygotsky’s (1962) work and other work that emphasizes sociocultural aspects of learning, rather than learning as an individual phenomenon. The differences in traditions have implications for how to study motivation—that one should not just look at individuals, but individuals’ part of a complex system, such as a classroom. In the commentary, she did not directly express concern with our decision to change the name of EEVT to SEVT, instead making the broader comments about the nature of situative approaches and how they differ from socio-cognitive ones. The second author has had conversations with her about these issues, and he and Nolen agree that collaborations of researchers from both perspectives can bridge the gaps between them, as long as the collaborators are “are clear-eyed about the fundamental differences and can work out how to work with them for mutual benefit” (Nolen, personal communication, March 24, 2024).

Another reason for the change was to emphasize more clearly the role of culture in the model. As can be seen in Figure 1, the model begins in the far left with a box devoted to the sociocultural and historical nature of life. The model was developed initially to capture the cultural phenomenon of girls being less likely to go into advanced math and science courses, majors, and careers. Thus, the constructs in the Cultural Milieu box focus on gender. As we stated in 2020, we are quite open for researchers to propose and assess other aspects of the cultural milieu and examine them in relation to children’s developing SCAs and STVs. The model should not be viewed as complete as is but fluid and situation based. Some of the constructs added to the cultural milieu box could be relatively broad ones that affect most people in a given culture; others could be much more specific.

Matthews and Wigfield (in press) provide one example of this elaboration process. To capture the cultural milieu in which many Black children and adolescents in the USA grow up, they proposed a variety of cultural circumstances, including systemic racism, power differentials, continued and even increasing school segregation, and others that many Black children face. They also described socialization features of the school and home environments, some problematic and some protective, that characterize Black children’s circumstances. They proposed that these circumstances or influences very likely affect Black children’s developing expectancies and values and urged researchers to look more closely at them.

It is important to make clear that we view cultural influences occurring throughout the model; that is, we do not view them as exogenous influences that only have impact at the outset. Rather, they are infused in each box. Again, the problem once again is due to the depiction of the model rather than how we conceptualize it and have conceptualized it. We are working to create a new, more multifaceted depiction of the model that will capture better how we see individuals’ expectancies and values being part of the particular situations they are in, and influenced by larger, systemic aspects of the cultures they are in. We anticipate it being more “Bronfenbrenner (1986) like,” in the sense of viewing the development of expectancies and values being enmeshed in and influenced by different levels of the environments and cultures in which they live. The new version of the model will be elaborated in our forthcoming book (Eccles, Wigfield, & Simpkins, in preparation).

We also stress the fact that proximal socializers (i.e., all of the proximally located individuals that make up each individual’s lifetime and space) are directly influenced both by their sociocultural context and the characteristics of the focal individual. Thus, for example, we hypothesized that parents would respond to their children differently as the children become older and that these changing responses will be influenced by socioculturally derived notions of the age appropriateness of the specific goals they might have at any given age as well as the age appropriateness of the characteristics and behaviors of the focal child (Eccles, 1993; Simpkins et al., 2015). The same would be true for the sex of the focal child, the race, ethnicity, nationality, and religion of the focal child, the sexual, racial, ethnic, religious identity of the child, etc. Furthermore, and tied to the point about the situated nature of the model, we assume that these processes accumulate over time to produce individuals who are uniquely positioned due to their own unique histories, memories, endowments, and their quite specific location in time and space to deal with their set of behavioral options at any one point in time. Like Nolen (2020), we agree that context is a changing system that includes all of the participants. Thus, individuals both learn from and co-create contexts as they participant in them.

The name change already is having an impact on researchers’ examination of students’ developing SCAs and STVs. Since the change there have been several symposia presented at conferences like AERA and APA that use SEVT rather than EVT. The researchers doing this work measure things more specifically, look at variation over the short term and longer term, and otherwise try to take seriously the idea that students’ SCAs and STVs are situationally bound, and fluid. To date, however, this work has not undertaken a careful analysis of the situations in which the studies have been done, other than to note the particular situation (e.g., introductory college physics classes, advanced college biology classes). To capture more fully a situative perspective, the linkages between characteristics of the situation and the psychological belief and values being measured will need to be studied more thoroughly. We urge researchers basing their work in SEVT also work with researchers taking a situative approach ala Nolen (2020).

To conclude this section with some broad recommendations regarding theory development, we suggest that theory developers be sensitive to research findings that either do support predictions or provide nuance to those predictions to be sure that the theory captures both the overall picture and subtleties in it. We also think that when there is good reason to do so changing or elaborating the nature of a given construct in the model, either based on research findings or due to theoretical considerations is a good way to keep even an “older” theory current. Although we have admiration for Bandura’s (1977, 1997) consistent definition of self-efficacy, constructs like attainment value and cost are still “works in progress” and so changing definitions (and measurement) illustrate progress. Moving beyond individual constructs to the theory as a whole changing the name of a theory to reflect developments in the field is (potentially at least) also a way to keep it current. Adding the single word “situated” to expectancy value theory seems to be having that effect.

Finally, it perhaps is worth commenting on “what can be tested” in this theory? We have heard suggestions that because of its size and scope, the theory is untestable. We agree that trying to test all of the proposed links in the model in one study is not something that would be possible. However, by validating constructs and testing various sets of predictive links in different parts of the model gradually, we can determine which parts of the overall theory have the most support and which either have not been supported, or not yet assessed. This perhaps is analogous to Ryan and Deci’s (2017) comments about building support for self-determination theory “brick by brick.”

What Are the Contributions of This Theory? How Has It Benefitted Educational Psychology Research, Practice, and/or Policy?

We noted earlier that the theory has guided and continues to guide a great deal of research on the development of students’ expectancies and subjective task values and their impact on decision making of different kinds. This is one way the theory has benefitted educational psychology research. With respect to educational policy, the broadest impact of our research is on the decisions made by many school systems in the 1990s to create middle schools that (when done right) better meet early adolescents’ developmental characteristics compared to traditional junior high schools. Another impact on educational practice is the intervention work based in the theory; we discuss that next.

Researchers have conducted numerous interventions to enhance individuals’ STVs, beginning with Hulleman and Harackiewicz’s (2009) study showing that a utility value intervention enhanced high school students’ interest in science and also their performance. Harackiewicz and colleagues subsequently have shown that utility value interventions positively influence other motivational beliefs and values, choices to continue taking courses in the area of the intervention, and grades, both in the short-term and long-term STVs; they have done these interventions with the students themselves and also their parents (e.g., Harackiewicz et al., 2012; see Harackiewicz & Priniski, 2018; Rosenzweig & Wigfield, 2016; Rosenzweig et al., 2022). Gaspard et al. (2015) have done successful utility value interventions focused on increasing the utility value of math for German high school students; interestingly, however, results of a recent replication study were not quite as strong (Gaspard et al., 2019).

Harackiewicz et al. (2015) implemented a utility value intervention in different groups of college students, including both first-generation and underrepresented minority students. Intervention group students’ grades improved more than did the control group students. Most importantly, the intervention was particular successful in improving first-generation-underrepresented students’ performance, meaning that it reduced the achievement gap between these students and majority students. Thus, these interventions may be particularly effective for groups who need them the most. Second, Harackiewicz and her colleagues have shown that these brief utility value interventions have both short- (within a semester) and longer-term effects such subsequent course choice, academic major choice, and career aspirations in college, (e.g., Asher et al., 2023; Hecht et al., 2019b). Asher et al. (2023) found (in a large scale RCT study) that their utility value intervention implemented in a gateway chemistry course improved college students’ persistence in STEM fields 2.5 years later, a rather remarkable finding. Importantly, and as was the case Harackiewicz et al. (2015), effects were stronger for the underrepresented minority students in the sample.

Hecht et al. (2019a) proposed several processes or mechanisms by which these long-term effects occur. They stated that recursive processes, or feedback loops where (for example) increased valuing of a course leads students to work harder in it, leading to further increases in the course’s value, and so on, can lead to long-term effects. Others include (1) nonrecursive processes where increases in task value promote positive change in other motivational beliefs such as ASCs or ESs, making the individual more likely to succeed in the class and take additional courses; (2) “trigger and channel” processes by which increased value for a subject area increases the degree to which students take advantage of existing opportunities to continue in that area (e.g., available classes in the subject, available majors); and (3) learning “habits of mind” that are conducive to succeeding in different classes. They are just beginning to disentangle how these processes separately and jointly help us understand the long-term success of utility value interventions.

One interesting aspect of this work to us was the choice to focus on utility value as the aspect of task value on which to intervene. Harackiewicz et al. (2014) posited that utility value is the most malleable of the task value components, and so most likely to change during interventions. Although this is possible, we believe other aspects of individuals’ task values can be enhanced by interventions, so suggest researchers extend the utility value intervention work to other aspects of STVs. In an important step in this direction, Rosenzweig et al. (2020) showed that an intervention designed to reduce college students’ perceptions of the cost of physics was as effective as a utility value intervention in increasing the students’ performance in physics. We also believe attainment value–based interventions should be developed. These could be designed to provide students with information on the link between potential associated job characteristics with the students’ goals and identities. Another focus would be how STEM provide opportunities to help others and work/collaborate with people as ways of attracting women into STEM fields, as Harackiewicz et al. (2012) did in their intervention with parents.

Rosenzweig et al. (2022) provide detailed suggestions on how to develop interventions focused on the other aspects of task value, as well as interventions designed to enhance both expectancies and different aspects of subjective task value. They address questions such as which are the most feasible aspects of task value on which to intervene, and also how and when it is worthwhile to intervene on multiple constructs including expectancies. In line with the new “situated” aspect of the theory, Rosenzweig et al. noted that intervention researchers should attend carefully to the characteristics and academic needs of the groups of students on whom they are intervening. Students struggling in school likely need interventions to boost that they can do the tasks along with boosting their sense of the utility of the task for them. Rosenzweig and colleagues’ recent work looking at students’ reasons for either dropping out of STEM fields or switching from one STEM field to another provide fertile ground for researchers to understand the challenges students face in different subjects. This fuller understanding should clearly impact both intervention design and success.

What Are the Virtues of the Theory?

Greene (2022) presented a variety of possible internal and external virtues of various theories. Internal virtues are specific to the theory itself; external ones focus on the theory in relation to other theories. We are somewhat selective in the amount of detail we provide on each of the virtues, providing more detail on the ones we think are most relevant to SEVT.

Beginning with scope, current motivation theories in educational psychology vary in their scope in a number of ways, from number of constructs to number of areas covered to number of links between constructs and the processes by which the constructs are connected, among others. Currently, in the field, there are arguably five major theories: attribution theory, goal orientation theory, self-determination theory, situated expectancy value theory, and social cognitive theory (to focus on the major theories presented in the 2020 special issue of Contemporary Educational Psychology) There are other theories or approaches that have emerged; Nolen (2020) calls her (and others’) situative views on motivation an approach rather than a theory. Complexity theory/complex dynamic system approaches (e.g., Hilpert & Marchand, 2018; Kaplan & Garner, 2020) are taking shape and challenging “traditional” linear models but so far have emphasized the complexity of motivation rather than focusing on particular well-researched constructs and links among them. The most fully developed model taking this perspective arguably is Kaplan and Garner’s (2017) dynamic system model of role identity. It is not a theory of motivation per se and space precludes full discussion of it; we thought it important to mention because of the criticisms researchers taking a complexity perspective aim at the five theories just mentioned. Moving forward it will be interesting to see whether there is integration of these perspectives. We believe that SEVT should be considered a complex and dynamic approach; Kaplan, Garner, and the second author currently are engaging in conversations about this to determine the extent of our agreement about this.

Returning to the five theories just mentioned, arguably self-determination theory and SEVT are the broadest in scope. Other theories, such as attribution theory and goal orientation theory, focus on fewer constructs and so potentially could be incorporated into theories broader in scope. Ryan and Deci (2020) posited that self-determination theory could be the all-encompassing theory, and they have incorporated goal theory into SDT. In SEVT, attributions are contained in the Interpretations of Experience box and goals in the self-schemata box, so it has the potential to be a more encompassing theory as well. Theories sometimes speak to different issues so we do not want to claim necessarily that SEVT could be the all-encompassing theory, but clearly its scope is broad with respect to constructs included, links among them, influences on them, and processes discussed.

Regarding unification, as we noted in the outset, Eccles-Parsons et al. (1983) worked to develop a unified approach by (1) taking constructs and postulates from different areas of psychology, particularly social, developmental, and educational psychology; (2) including a broad array of motivation constructs from different kinds of motivation theories, notably “historic” expectancy-value theory, attribution theory (the interpretations of experience box in Figure 1), social cognitive theory (the construct of expectancies), achievement emotions, goal theories, and identity theories. As can be seen in Figure 2, there are a broad array of parent socialization variables included. We noted at various places in this article that we also have written extensivity about a variety of school socialization practices and their impact (while acknowledging that those have not all been included in the graphic depictions of the model yet; and (3) studying a variety of achievement domains or areas to determine how broadly the predictive links could be obtained.

Is the theory parsimonious? Perhaps we should ask if parsimony is really a virtue? There appears to be some debate about that in the field. We noted earlier relatively new work in the motivation field focused on the complexity of motivation and how it is influenced by many different aspects of day-to-day practices in classrooms. Proponents of these approaches (e.g., Hilpert & Marchand, 2018; Kaplan & Garner, 2020) are critical of more “traditional” social cognitively, post-positivistic based theoretical approaches including EEVT/SEVT as being too linear, deterministic, and simplistic (read parsimonious?) in their depiction of motivation. Perhaps in a post post-positive world, parsimony is no longer considered a desirable feature of a good theory.

Turning to plausibility and the related virtue of accuracy, we believe the evidence summarized in this article and presented in the literally hundreds of articles that have utilized EEVT/SEVT as their theoretical base provide strong evidence for the plausibility of the theory. We acknowledge that we have not reviewed that evidence here; reviews can be found in Eccles and Wigfield (2020, 2023), Wigfield and Eccles (2020), and Wigfield et al. (2016), and elsewhere. The constructs and their links are prima facie plausible, and the evidence provided by the various studies provides a solid foundation of support for the constructs and premises in the theory. In other words, the evidence makes a good case for the theory’s accuracy.

We think the theory has been and will continue to be quite fruitful in all the ways listed in Greene’s (2022) Table 1. We and other researchers continuously develop new research questions and hypotheses based in the theory. As Eccles and Wigfield (2020) discussed, the current version of the theory as presented in Figure 1 is meant to be representative of constructs and linkages covered in the theory rather being an exhaustive set. So, the theory is expandable to investigate other research questions and hypotheses. Finally, in terms of practical applications, the extensive number of intervention studies guided by the theory arguably make it the current motivation theory with, if not the most, certainly many practical applications. The intervention research has influenced educational practices at different levels of education. We believe these points apply equally well to the practicality point in the list of external criteria.

With respect to internal consistency/coherence in our view, there is little that is contradictory about the phenomena in the theory. This is because of its careful development from the different fields noted above, as well as its basis in long-standing theories in the motivation field. Eccles-Parsons and colleagues purposely designed the theory to be internally consistent. Furthermore, the research done testing various key predictive links in the theory has provided good support for them; results have not been contradictory in any sense of that term.

The mechanisms behind the constructs and relations expressed in the theory are a work in progress to some degree. One way that mechanisms are depicted is the arrows linking various constructs. As Eccles and Wigfield (2020) stated, “The arrows represent hypothesized processes and links that play out over time as well as within smaller units of time when specific task choices are being made” (101859). Arrows of course do not themselves indicate what those mechanisms or processes are, but we have written about them in other places (e.g., Eccles, 2005, 2009; Wigfield et al., 2016, Wigfield et al., 2017). One set of mechanisms or processes are how individuals process information they receive about their performance and how that impacts their developing expectancies and values. Examples of such processes are temporal comparisons where people judge how they are doing now compared to how they were doing before, social comparisons or how we compare ourselves to others, and dimensional comparisons or comparisons of our performance in one domain vs another (see Wigfield et al., 2020 for discussion). Other processes are less well understood; Eccles and Wigfield (2020 and elsewhere) have written about how we do not have a full understanding of how individuals weigh different information they have to determine how much they value an activity, or how they form their hierarchies of both expectancies and values. In the socialization area, we have noted in different places in this article how teachers and parents (and other socializers) impact children’s developing expectancies and values through many different aspects of their relationships, along with structural issues in the home and school.

A particularly important issue to continue to address regarding these mechanisms is how their influence change over time, both with respect to how children of different ages understand them, as well as how mechanisms such as the quality of teacher-student relations themselves change over time. Then of course there is variation in things like teacher-student relations at a given age or grade level. Clearly these mechanisms are complex and multifaceted, and greatly influenced by the situations in which they occur.

We will group testability and specificity together. On the one hand, the model has been critiqued as being untestable due to its size and scope. As noted earlier, we agree that the full model never will be able to be assessed all at once as it is just too big and complex to do so. Having said that we think there are many ways to create meaningful sets of constructs in the model and examine connections across them to test various specific predictions in the model, from how expectancies and values predict performance and choice to how parents’ messages about children’s ability impact their developing expectancies and values. That is, although the model is large, the constructs in it are (for the most part) specific enough that measures can be and have been developed, allowing for testing of different predictions. A great deal of work has been done around the world to examine various predictions from, and we are pleased that the model continues to stimulate much research.

Turning to the other two external criteria (analogy and practicality), there are many points of agreement between SEVT and other theories. Social cognitive theory focuses on how self-efficacy predicts performance and choice, as does SEVT. Attribution theory has to do with the explanations individuals give for their outcomes, and such interpretations are a key part of the information students use to form their expectancies and values. Goals and goal orientations are also key constructs in the theory; one of the boxes is labeled “Goals and Self Schemata.” Eccles and Midgley (1989) and other have written about the importance of support for autonomy and structure in the development of motivation, key tenets of SDT. The list goes on.

Having said that it is interesting that there have not been direct tests of one theory vs. another, for the most part, to determine which might provide the best explanation of different outcomes. Why is that? Possibly because extant theories do not contain enough similar constructs to pit one against the other. Another is that measures developed within a given theory often are at different levels of specificity. For instance, many measures in self-determination theory are domain general; those based in other theories are more specific. Anderman (2020) has questioned whether we need all the current theories; moving forward this is an important issue to address and so we hope more direct tests can be made. An example we can mention is that our work has shown that both expectancies and subjective task values are important predictors of outcomes, rather than expectancies, as social cognitive theory would predict.

With respect to practicality, we think the intervention work based in the theory already is having an impact on how teaching is done at a variety of institutions across the county, both post-secondary and k-12. The intervention researchers are working with instructors to change their teaching practices in order to emphasize the utility value of what their students are learning, to give just one example. In that sense, the theory is useful to society.

What Do You See as Some Promising “Next Steps” or “Open Questions” for Future Development of the Theory?

There are a myriad of possible next steps for the theory and research based in it, and researchers are generating new topics frequently; an example is the 2023 SEVT-based symposium held at APA in which authors presented papers focused more on the situated nature of expectancies and subjective task values, their ties to self-regulated learning, and their function in different groups. Eccles and Wigfield (2020) provided a number of suggestions, such as investigating more fully the interplay of the different aspects of task in determining overall subjective task value and the factors influencing the formation of STV and ASC hierarchies. We think the analyses to address these issues will of necessity be quite complex and agree with Nagengast and Trautwein’s (2023) view that theory and method need to be closer in sync with each other for the field to advance in ways that help understand the complexity among these relations.

Speaking of methods, one issue that needs addressing moving forward is how best to measure expectancies, values, and many of the other constructs in the model. We point to Pajares’ (1996) seminal article on measuring self-efficacy and how the disparate ways of measuring it left it quite uncertain what was being measured in any given study purportedly studying self-efficacy. We hope this will not be such a big issue for SEVT; however, there are issues to address. We address three. Eccles and Wigfield developed measures of the major constructs many years ago; they had and have good psychometric properties but also have certain limits. One mentioned earlier is that measures of attainment value we developed focus on importance only and have not brought in the identity aspects of attainment Eccles has discussed in greater detail more recently. There are opportunities for researchers focused on identity and SEVT-based researchers to work together to develop such measures. We mentioned earlier the growing body of work on cost and noted some of the new measures of it. An important challenge for those interested in studying cost is that these measures look quite different even though they are measuring purportedly the same construct. We think it crucial for researchers studying cost to come together to try to agree on what its components are and how best to measure them. Last, one of the ways researchers taking the new “situated” approach is to give measures to study participants more frequently, even as much as once a week. Such measures by necessity must be brief in order to avoid “scale fatigue” on the part of the participants. Yet are such measures analogous to the longer measures used?

SEVT has been the theoretical basis for much work on gender differences in motivation and an increasing amount of work on ethnic group differences in motivation (e.g., Diemer et al., 2016; Peck et al., 2014), but more work needs to be done on how culture, ethnicity, gender, and (more importantly) their interactions impact the development of individuals’ expectancies and values (see Tonks et al., 2018, and Wigfield & Gladstone, 2019, for discussion of culture and ethnicity’s impact on the development of children’s expectancies and values). When studying ethnicity researchers basing their work in SEVT should address how experiences of racism, discrimination, and oppression influence children’s developing SCAs and STVs. Kumar et al. (2018) note that most achievement motivation theories (including EVT) have not attended nearly enough to the impact of these powerful forces on students’ motivation. As noted earlier, Matthews and Wigfield (in press) proposed ways to racialize certain aspects of the model, notably the cultural milieu box and socialization box to understand better the development of Black children’s motivational beliefs and values. They connect SEVT both to critical race theory (Ladson-Billings & Tate, 1995and Neblett et al. (2021) racial socialization model that describes ways Black parents can help their children deal with experiences of racism and discrimination, and instill a strong sense of racial identity, something that has been shown to relate to Black students’ achievement in school. Their article is the first attempt to connect systematically these discrete bodies of work as a way to better understand the development of Black students’ motivational beliefs and values.

With respect to the socialization aspect of the model, researchers have focused primarily on the impact of different parenting practice and school environmental factors on children’s developing STVs and ASCs. Many other influences need attention. Building on this point, we think it is time to expand the influences contained in the different socialization focused boxes to develop these ideas more formally. As with the issues noted above, testing these influences in sophisticated ways will mean more situated and frequent measures of the constructs, and complex modeling analyses (among other things) to examine relations among them. In these and other ways, we think SEVT and dynamic complex system approaches have much in common and look forward to conversations about their synergy.

To conclude, SEVT remains vibrant, increasingly complex, and relevant to understanding choices individuals make and their performance on different activities. Yet there are many ways it can be expanded, and many questions yet to address. We looks forward to the next generation of research based in it.

Notes

When talking about work Eccles and Wigfield did together we use the pronoun “we,” or more generally, use first person. When talking about EVT work we did not do together we will use our names. Note that Jacque Eccles initially was J. E. Parsons, then J. Eccles-Parsons, and now J. S. Eccles.

Because this article is on theory development, we focus on our own longitudinal studies designed to test the model. Research from around the world has confirmed both the “structure” of the constructs and the predictive links of SCAs and STVs to performance and choice (see Eccles & Wigfield, 2020, 2023; Wigfield & Eccles, 2020; Wigfield et al., 2016 for review).

References

Anderman, E. M. (2020). Motivation theory in the 21st century: Balancing precision and utility. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 61, 101864

Archambault, I., Eccles, J. S., & Vida, M. N. (2010). Ability self-concepts and subjective value in literacy: Joint trajectories from grades 1–12. Journal of Educational Psychology, 102(4), 804–816. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021075

Asher, M. W., Harackiewicz, J. M., Beymer, P. B., Hecht, C. A., Lamont, L. B., Else-Quest, N. M., Priniski, S. J., Thomas, J. B., Hyde, J. S., & Smith, J. L. (2023). Utility-value intervention promotes persistence and diversity in STEM. Psychological and Cognitive Sciences, 120, 1–6.

Atkinson, J. W. (1957). Motivational determinants of risk-taking behavior. Psychological Review, 64, 359–372. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0043445

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. W. H. Freeman.

Bandura, S. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215.

Barron, K. E., & Hulleman, C. S. (2015). Expectancy-value-cost model of motivation. In J. S. Eccles & K. Salmelo-Aro (Eds.), International encyclopedia of social and behavioral sciences: Motivational psychology (2nd ed.). Elsevier.

Battle, A., & Wigfield, A. (2003). College women’s value orientations toward family, career, and graduate school. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 62, 56–75.

Battle, E. (1965). Motivational determinants of academic task persistence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 2, 209–218.

Battle, E. (1966). Motivational determinants of academic competence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 4, 534–642.

Beymer, P. N., Flake, J. K., & Schmidt, J. A. (2023). Disentangling students’ anticipated and experiences cost: The case for understanding both. Journal of Educational Psychology, 115(4), 624–641.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1986). Ecology of the family as a context for human development: Research perspectives. Developmental Psychology, 22, 723–742.

Carnegie Council on Adolescent Development. (1989). Turning points: Preparing American youth for the 21st century. Carnegie Foundation.