Abstract

Students are the central agent in self-assessment; therefore, their perceptions are crucial for successful self-assessment. Despite the increasing number of empirical studies exploring how students perceive self-assessment, systematic reviews synthesising students’ perceptions of self-assessment and relating them to self-assessment implementation are scarce. This review covered 44 eligible studies and synthesised findings related to two key aspects of students’ perceptions of self-assessment: (1) usefulness of self-assessment; and (2) factors influencing their implementation of self-assessment. The results revealed inconclusive findings regarding students’ perceived usefulness of self-assessment. Although most studies reported a generally positive perception of self-assessment among students, some studies revealed students’ skepticism about its usefulness. Usefulness was influenced by specific individual factors (i.e., gender, age, and educational level) and instructional factors (i.e., external feedback, use of instruments, and self-assessment purpose). Additionally, implementation was influenced by specific individual factors (i.e., perceived usefulness, affective attitude, self-efficacy, important others, and psychological safety) and instructional factors (i.e., practice and training, external feedback, use of instruments, and environmental support). The findings of this review contribute to a better understanding of students’ perceptions of self-assessment and shed light on the design and implementation of meaningful self-assessment activities that cater to students’ learning needs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Self-assessment has drawn increasing interest among researchers and practitioners due to its potential in promoting learning (Andrade, 2019; Brown & Harris, 2013). The positive impact of self-assessment on both academic performance (e.g., Brown & Harris, 2013; Topping, 2003; Yan et al., 2022) and affective outcomes (e.g., Panadero et al., 2017; Zhan et al., 2023; Sitzmann et al., 2010) has been well documented. Despite the generally positive impact, findings of meta-analyses (e.g., Brown & Harris, 2013; Yan et al., 2022) suggest that the self-assessment process is complex and its impact on student performance varies across contexts. As self-assessment is a student-directed process, students’ perceptions of self-assessment play a crucial role in its implementation and influence its effect. Although there are an increasing number of empirical studies exploring how students perceive self-assessment, to our knowledge, there is no systematic review on this topic. Thus, this review has aimed to synthesise the findings on two key aspects of the students’ perceptions of self-assessment: usefulness and factors influencing implementation. A nuanced understanding of these aspects is critical to guide the design and implementation of self-assessment in future research and practice. The pedagogical insights generated from the synthesis can be used by researchers and practitioners to increase students’ engagement in self-assessment and maximise its positive impact. This article first outlines the conceptualisation of self-assessment and the critical role of students’ perceptions in their self-assessment practices, then discusses the limitations of existing reviews. Next, methods applied in this review are described, and results are reported against the research questions. The article concludes by discussing implications for educational research and practice.

Student Self-assessment

There are diversified descriptions of self-assessment in the literature (e.g., Andrade, 2019). Panadero et al. (2016) defined self-assessment as “a wide variety of mechanisms and techniques through which students describe (i.e., assess) and possibly assign merit or worth to (i.e., evaluate) the qualities of their own learning processes and products” (p. 804). This definition was adopted in the current review as it covered a broad spectrum of self-assessment implementation. Self-assessment can be as simple as “guessing a grade”, or can be a complicated process during which, students engage in different actions, such as determining standards and/or criteria, seeking feedback information, reflecting on one’s own performance, making and calibrating self-assessment judgement (Panadero et al., 2016; Yan & Brown, 2017).

Self-assessment can happen as an explicit activity (e.g., self-assessment exercises organised in classrooms) or occur in an implicit fashion (e.g., spontaneous self-questioning during learning) (Nicol, 2021; Panadero et al., 2019; Yan, 2022). The current review focused on explicit and/or structured self-assessment. Despite the value of implicit self-assessment, this decision was made for two practical reasons. Firstly, it is easier to study explicit self-assessment with observable evidence. Secondly, by analysing the process of explicit, structured self-assessments, crucial pedagogical insights can be generated for teachers to refine teaching and for students to advance learning.

The effect of self-assessment on students’ learning performance has been studied in numerous studies. For example, Topping (2003) concluded in a narrative review that self-assessment could improve both the effectiveness and quality of learning. Brown and Harris (2013) also found similar results by reviewing 23 studies, which covered a wide range of self-assessment operationalisations. The effects ranged from -0.04 to 1.62 (Cohen’s d), with a median effect between 0.40 and 0.45. In a more recent meta-analysis, Yan et al. (2022) synthesised 626 effect sizes from 175 independent studies. The results indicated that self-assessment had medium to large effects (g = 0.585) on academic performance. However, all these reviews revealed that the effect of self-assessment varies across contexts. For example, in Yan et al.'s (2022) meta-analysis, despite the overall positive effects of SA, negative effects were reported in 22.8% of studies. These findings suggest that self-assessment is a complex process and may be influenced by a wide range of factors. One of the crucial factors could be students’ beliefs/conceptions of self-assessment because how students perceive self-assessment might affect their behaviours in the self-assessment process, which, in turn, influence the effect of self-assessment.

The Importance of Student Beliefs

It is generally accepted that learning belief significantly affects learning behaviours (van der Kleij & Lipnevich, 2021). For example, students’ control and self-efficacy beliefs significantly predict their behavioural engagement in mathematics (Gjicali & Lipnevich, 2021). In addition, students’ adaptive perceptions of high-stakes assessment are associated with the use of self-regulated learning strategies and knowledge transferability (Cho et al., 2020). Students’ perceptions about assessment also influence their learning behaviours and the effects of assessment. Brown and colleagues have studied students’ conceptions of assessment, particularly the purposes of assessment (e.g., Brown, 2011; Brown & Hirschfeld, 2008; Brown & Wang, 2013). They found that students’ conceptions of assessments influenced student learning-related behaviours, such as self-regulation (Brown, 2011) and academic achievement (Brown & Hirschfeld, 2008). Since self-assessment is a student-directed process that heavily relies on students’ active role in the process (Panadero et al., 2019; Yan, 2022), students’ perceptions of self-assessment might determine whether self-assessment can be implemented as intended and how the self-assessment can impact their learning. Students’ misperceptions of self-assessment may be a significant obstacle to its implementation (Panadero et al., 2016). For example, if students perceive feedback received in the process of self-assessment as humiliating and dissatisfying, their learning will be hampered (Tavsanli & Kara, 2021). Students’ conceptions of self-assessment cover different aspects. Among them, perceived usefulness and factors influencing implementation are of utmost importance because both aspects substantially impact students’ engagement in self-assessment and the learning gains from self-assessment.

Students’ Perceived Usefulness of Self-assessment

Students’ perceived usefulness of self-assessment is crucial because it could be a necessary condition precedent to actual engagement in self-assessment. Perceived usefulness was found to be the most powerful predictor of students’ intentions to conduct self-assessment (Yan, Brown et al., 2020). Our preliminary literature search also showed that the perceived usefulness of self-assessment is one of the most popular topics among studies examining students’ perceptions of self-assessment.

Most students who possessed positive beliefs about self-assessment acclaimed that it helped them gain independence, take responsibility for learning, grow in confidence, work in a structured manner, and be analytical and critical during learning (Bourke, 2014; Siow, 2015; van Helvoort, 2012). However, the findings are inconsistent in that students’ perceived usefulness of self-assessment is not universal, and it is affected by a wide range of factors, such as education level, self-assessment instruments, and the environment (Andrade, 2019; Hill, 2016).

Students’ Perceived Factors Influencing the Implementation of Self-assessment

Factors influencing self-assessment implementation in students’ perceptions are critical because they affect students’ actual behaviours in the self-assessment process and, therefore, determine the learning impact of self-assessment. Past studies have provided evidence of the association between personal factors and the implementation of self-assessment. For example, Yan, Brown et al. (2020) found that attitude, subjective norms, self-efficacy, and perceived controllability were significant predictors of self-assessment intention and practice. Students are more likely to engage in self-assessment if they realise it is a crucial learning tool (Logan, 2015; Tavsanli & Kara, 2021). Important others’ (e.g., teachers and peers) beliefs also substantially influence students’ implementation of self-assessment (Andrade & Du, 2007; Harris & Brown, 2013). Furthermore, students’ sense of psychological safety also influences students’ self-assessment actions (Harris & Brown, 2013; Yan, Brown et al., 2020).

In addition to individual factors, instructional factors also influence students’ self-assessment. For instance, instructional scaffoldings of self-assessment are usually considered helpful, such as rubrics and checklists (Andrade & Du, 2007; Wang, 2017), or receiving feedback from teachers and peers (Harris & Brown, 2013; Orsmond et al., 1997). Relevant practice and training can enhance students’ confidence in self-assessment (Wong, 2016, 2017) and change their attitude towards self-assessment so that they are more likely to self-assess (Perera et al., 2010; Wang, 2017). In contrast, lacking experience in assessment could be a barrier for students to carry out self-assessment (Hanrahan & Geoff, 2001; Zekarias, 2023). Moreover, it is useful to develop students’ confidence in their skills and abilities to facilitate self-assessment (Butler & Lee, 2006; Wolffensperger & Patkin, 2013). Additionally, the class climate (e.g., emotional support from peers) is also a crucial instructional factor that could encourage the implementation of self-assessment (Sargeant et al., 2011).

Prior Review of Students’ Perceptions of Self-assessment

As the empirical studies on self-assessment accumulate with time, there is an increasing number of review studies. However, most reviews focus on either the effectiveness of self-assessment interventions (e.g., Topping, 2003) or the validity (or accuracy) of self-assessment (e.g., Li & Zhang, 2020; Sitzmann et al., 2010). Students’ perceptions of self-assessment and how such perceptions relate to the implementation of self-assessment have not attracted sufficient attention. The only exception that the authors are aware of is a two-paragraph section in Andrade’s (2019) review that discussed 15 studies investigating students’ perceptions of self-assessment. The results show that students’ perceptions of self-assessment were influenced by education level, self-assessment instruments, and the purpose of SA. For example, college and university students usually understand the purpose of self-assessment and appreciate its value in optimising the learning process and facilitating self-regulated learning. In contrast, younger children tend to have unsophisticated understandings of the purposes of self-assessment, which may result in poor implementation of the self-assessment process. Andrade’s review also shows that students are likely to have a positive perception of self-assessment if they have the opportunity to develop or use their own criteria, rubrics, or checklists to guide their self-assessment and the subsequent revision of their work. Furthermore, students’ perceptions of self-assessment can be negatively influenced if the assessment serves a summative purpose.

As Andrade’s (2019) review aimed to report on “what has been sufficiently researched and what remains to be done” (p. 5), the discussion on students’ perceptions is merely one of the reviewed topics, among many others. Its literature search did not specifically target this topic and included only a small number of relevant studies (N = 15). In addition, it did not explicitly define which aspect(s) of students’ perceptions were being reviewed. Hence, despite the insights generated, the short section in Andrade’s (2019) review does not allow a detailed elaboration of how students perceive self-assessment and how students’ perceptions of self-assessment relate to its implementation.

The Current Review

The above discussion shows that despite the crucial role of students’ perceptions of self-assessment and the increasing interest in studying this topic, a synthesis of the available literature is lacking. The current review has aimed to advance the understanding of students’ perceptions of self-assessment and explore how such perceptions were related to the implementation of self-assessment. In particular, the following research questions were investigated:

-

RQ1- What are the characteristics of studies on students’ perceptions of self-assessment?

-

RQ2- How do students perceive the usefulness of self-assessment?

-

RQ3- What factors affect students’ perceived usefulness of self-assessment?

-

RQ4- What factors affect students’ implementation of self-assessment?

Method

To ensure the method was rigorous and reproducible, the procedures were developed based on the guide of the systematic reviews (Petticrew & Roberts, 2006). To be precise, there have been multiple steps involved in this review, including developing research questions, identifying search strategies, conducting literature searches, formulating inclusion criteria and selecting relevant articles, extracting the data, and collating, summarising, and reporting the results.

Search Strategy and Inclusion Criteria

Six key terms were used for the literature search: perception, conception, attitude, value, belief, and self-efficacy, all of which refer to the mental interpretations of perceived stimuli and information (Bonner, 2016). These terms were combined with self-assessment, or self-evaluation/monitoring/reflection/review/feedback/rating/grading for the search. For maximum coverage of the literature, all studies that addressed students’ perceptions about self-assessment were included, even if not the central topic of the study.

The search was conducted in November 2021, using two databases, ERIC and PsycINFO, for searching titles and abstracts. These databases were selected for this study due to their extensive coverage of research in the fields of education and psychology. Given the available filters, the search was conducted on peer-reviewed journal articles written in English from all available years. Simultaneously, studies recommended by authors and experts in this field were also added to the article pool generated from the database search. Duplicates were removed prior to identifying whether the studies related to the research questions. Four inclusion criteria were used in the screening, including (1) the study examined students’ perceptions of self-assessment; (2) it presented empirical results; (3) it was published in a peer-review journal; and (4) it was written in English.

Data Extraction

After removing duplicates, 1,864 publications were prepared for screening using the four inclusion criteria. A two-step selection was then used to determine which studies would be included. The first step was to screen the titles and abstracts of the articles in accordance with the inclusion criteria. Two rounds of quality checking were conducted. Firstly, two researchers independently screened a random sample of 30 studies according to the inclusion criteria. The degree of agreement was 87%, and a meeting was held to resolve discrepancies until a mutual agreement could be reached. Secondly, the two researchers independently screened another random sample of 30 studies. The degree of agreement increased to 93%. The researchers further discussed the reasons underlying discrepancies to ensure a consistent understanding of the inclusion criteria. The main screening was then conducted on all identified records. A total of 1,797 studies were excluded for failure to meet the inclusion criteria, resulting in 67 records that proceeded to the next step.

In the second step, the full texts of the 67 studies were independently read by two researchers. Each study was coded as include or exclude, and all discrepancies between the two coders were resolved through mutual agreement. A total of 23 studies were excluded due to two reasons, i.e., not addressing RQs (N = 18) or not presenting empirical data (N = 5). This yielded a total of 44 qualified studies for the current review. Figure 1 illustrates the process of the literature search, screening, and inclusion.

The selected studies were coded using a structured data extraction template specifically developed for this review. A pilot coding was conducted with two researchers independently coding 15 randomly selected studies using the template. The inter-rater reliability was 0.91. A consensus was reached via discussion on all disagreements, and the coding template was further clarified and refined accordingly. An iterative approach was used for defining the categories of factors in the data extraction. The final version of the data extraction form consisted of the following sections: study title, author name, year of publication, abstract, country/region, educational level (kindergarten through twelfth grade [K-12]/higher education), research design, self-assessment operational definition, data collection methods on self-assessment perception, sample size, subject area, characteristics of self-assessment, perceived usefulness and its influencing factors, and factors influencing students’ implementation of self-assessment.

Results

In this section, results are reported against the four RQs. The characteristics of the included studies (RQ1) are first described. Then, students’ perceived usefulness of self-assessment (RQ2) and factors influencing it (RQ3) are reported. Finally, the factors that affect students’ implementation of self-assessment (RQ4) are presented. For RQs 2 to 4, included studies are mentioned only if they have presented empirical data addressing that particular RQ.

RQ1- What Are the Characteristics of Studies on Students’ Perceptions of Self-assessment?

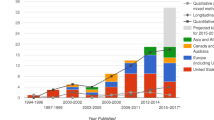

An overview of the basic information of the 44 included studies is provided in Table 1. The research context, research design, sample size, and data collection method for students’ perceptions are summarised in the table. The publication years of included studies ranged from 1997 through 2021. Included studies were conducted in 22 different countries/regions, with the UK (N = 7) and the USA (N = 7) appearing most frequently, followed by Singapore (N = 4), Hong Kong (N = 3), and New Zealand (N = 3). Over 70% of the included studies (N = 31) were conducted in higher education, while 13 studies were carried out in the K-12 context. The studies covered a broad range of disciplines/subjects, with language subjects being the most studied discipline (N = 9).

Various designs (i.e., quantitative, qualitative, and mixed) were employed in the included studies. Regarding the methods for collecting data on students’ perceptions of self-assessment, the three most frequently used methods were: survey (N = 26), interview (N = 14), and focus group interview (N = 11). As some studies applied multiple methods, the sum of different categorisations was larger than the total number of studies. The survey sample sizes varied dramatically across studies, ranging from 15 to 1,425. Most surveys consisted of close-ended questions, with only three studies (i.e., Hill, 2016; Logan, 2015; Pidduck & Bauer, 2021) including open-ended questions. The sample sizes for interviews/focus group interviews were much smaller, ranging from five to 130. The frequency of data collection methods slightly differed in the K-12 and higher education contexts. In K-12, survey and interview had the same usage rate (N = 6, 42.9%), but focus group interview was rarely used (N = 2, 14.3%). In higher education, the most popular method was survey (N = 20, 55.6%), followed by focus group interview (N = 9, 25.0%) and interview (N = 7, 19.4%). In addition, worksheets and reflective journals were also used to explore students’ perceptions of self-assessment. In Hanrahan and Isaacs’ (2001) study, data were collected through worksheets with an open-ended question concerning the pros and cons of performing self-assessment on the essay assignment. In Wang’s (2017) study, a reflective journal was used to understand students’ beliefs about rubrics used in self-assessment.

RQ2- How Do Students Perceive the Usefulness of Self-assessment?

The studies included in this review indicate that students generally hold positive perceptions of self-assessment. Among the 12 studies that provided quantitative data on students’ perceived usefulness of self-assessment (e.g., 1, 3, 5, 16, 18, 19, 24, 27, 30, 32, 34, 44), the results suggested a positive perception, as indicated by an average score higher than the midpoint of the Likert-type scale or more than 50% of positive responses. A consistent finding in many studies is that students report that self-assessment helps them understand their own abilities/performance, identify their weaknesses or missing pieces in their learning, and inform the direction of the subsequent learning (1, 11, 12, 16, 17, 18, 22, 26). Students also regard self-assessment as a method to take control of their learning (5). In addition, self-assessment can motivate students to apply more adaptive learning strategies (11) and build their confidence in learning subjects (17). In students’ opinions, self-assessment is not only useful for learning enhancement, but also a valuable tool for their future career/employment (8, 10).

Despite the generally positive perception, some studies revealed students’ suspicion about the usefulness of self-assessment, especially when self-assessment was not accompanied by external feedback. For example, Evans et al. (2005) reported that medical postgraduates and trainees did not consider self-assessment useful if there was no immediate feedback from trainers (11). Some students in Strobl’s (2015) study felt unable to achieve progress without teacher feedback after self-evaluation because of their doubt about self-assessment accuracy (36). In Al-Kadri et al.’s (2012) study, medical students felt that self-assessment did not increase their learning and motivation. For instance, one student said, “it looks like a good idea, but actually, in real life, it is just a matter of formality … I don’t give it importance. It doesn’t change the way I study or approach my patients” (2).

Some studies highlighted the diversity in students’ perceived usefulness of self-assessment. For example, in Hanrahan and Isaacs’s (2001) study, some students reported self-assessment might not be useful because “the assignments I have handed in are usually the best that I can produce, so I would find it hard to mark my own assignment”, others perceived it helpful in promoting critical thinking and improving the quality of their assignments (14). Another study revealed that some students perceived self-assessment as beneficial for learning, but not for impression management (i.e., managing the tutor’s impression of their performance), while other students held the opposite idea (i.e., self-assessment is helpful for impression management instead of learning) (20).

RQ3- What Factors Affect Students’ Perceived Usefulness of Self-assessment?

A total of 17 studies have examined factors influencing the students’ perceived usefulness of self-assessment (1, 2, 4, 6, 7, 8, 11, 12, 19, 22, 31, 33, 34, 36, 39, 40, 42). These factors could be categorised into two groups, i.e., individual and self-assessment design factors.

Individual Factors

Among the included studies, five investigated the influence of individual factors, including gender, age, and educational level, on students’ perceptions of the usefulness of self-assessment (1, 6, 7, 12, 31).

No study reported a significant difference in students’ overall perceived usefulness of self-assessment across genders. For example, girls and boys from Grades 2, 4 and 6 showed similar attitudes toward self-evaluation (e.g., ‘do you think self-evaluation helps you do better in school?’) (31). In Adediwura’s (2012) study, both male and female students reported that self-assessment had a positive impact on their self-efficacy and autonomy in learning mathematics (1).

Age is an important factor influencing students’ perceived usefulness of SA. For example, Gashi-Shatri and Zabeli (2018) found that 10th—12th grade students (15–18 years old) believed that self-assessment helped them more than 6th—9th grade students (12–14 years old) (12). Similarly, Bakx et al. (2002) found that, compared with first-year and second-year university students, fourth-year students had a more positive perception of self-assessment (6).

Concerning educational level, a proxy variable of age, primary school students noted that teacher-directed assessment helped them understand what they had learned or how much they had learned, but self-assessment might be less useful because it was hard for them to self-assess accurately. In contrast, secondary school students had a more sophisticated conception of self-assessment in that self-assessment can indicate learning based on determining learning goals and predetermined criteria (7).

Instructional Factors

A total of 16 studies investigated factors related to self-assessment design influencing students’ perceived usefulness of self-assessment (2, 6, 11, 12, 19, 22, 30, 31, 33, 34, 36, 39, 40, 42). The most frequently reported factors were external feedback (2, 6, 11, 12, 22, 31, 33, 40), use of instruments (11, 34, 36, 39, 40, 42), and self-assessment purpose (2, 4, 8, 40).

External Feedback

Self-assessment with external feedback, mainly from teachers, was perceived to be more valuable by students (2, 6, 11, 12, 22, 31, 33, 40). This is because teacher feedback on the quality of self-assessment helps make clear expectations of learning tasks and identify areas where they need to devote more time (31). Medical students believed that the absence of supervisors’ formative feedback was a barrier to informed self-assessments of clinical performance (33). Additionally, Al-Kadri et al. (2012) found that undergraduate medical students believed that self-assessment did not have a beneficial impact on learning strategies or outcomes when it was not accompanied by supervisor feedback (2). Timely feedback is particularly valued. In Ndoye’s (2017) study, students reported that feedback helped them take advantage of self-assessment, especially for live feedback that is given simultaneously with the work (22). Another study reported that all the interviewed medical postgraduates and trainees (N = 6) did not consider self-assessment useful due to a lack of immediate feedback from trainers (11). In addition, 10th—12th grade students placed a higher value on the feedback on the self-assessment process than 6th—9th grade students (12) or multimedia assessment with a self-assessment element (6). In addition to the lack of feedback, low-quality feedback also has a negative impact. For example, Wanner and Palmer (2018) also examined the role of peer feedback in self-assessment processes. They reported that some participants felt the self-assessment did not help enhance their performance due to poor or contradictory peer feedback (40).

Use of Instruments

Students indicated that self-assessment instruments made self-assessment more useful to their learning (11, 34, 36, 39, 40, 42). Students felt suspicious of the usefulness of self-evaluation when they have to do it without an appropriate reference of comparison (36). Compared with checklists and learning logs, students regarded rubrics as the most helpful tool (42). Students perceived rubrics as a reference for meaningful self-assessment (34). With the assistance of the rubric, students could pinpoint errors in their essays (40). In Wang’s (2017) study, university students suggested using rubrics in self-assessment to determine what and how they should do throughout all three stages of self-regulated learning: a) in the forethought stage, rubrics assisted them in setting goals and deciding learning strategies; b) in the performance stage, rubrics facilitated their self-monitoring behaviours; and c) in the self-reflection stage, rubrics guided them to identify the strengths and weakness as well as supporting the development of self-feedback. Moreover, students reported five factors affecting the effectiveness of rubrics during self-assessment in the EFL writing class, including the rubric’s coverage and structure, descriptors of performance quality, score range, domain knowledge about writing, and length of intervention (39). In addition to rubrics, other instruments are also useful. For example, both the global rating scale and checklist scales were perceived to be useful for self-assessment by medical trainees. Relatively, the global rating scale (i.e., a Likert-type scale to evaluate attributes relevant to the performance) was preferred to the checklist scale (i.e., a list of certain tasks that had been performed correctly) because the correct or incorrect options of the latter were too rigid (11). In sum, self-assessment was perceived as more useful when instruments were available, and rubrics appeared as the most popular instrument in self-assessment.

Self-assessment purpose

The purpose of self-assessment may influence students’ perceived usefulness. Although it is conventional to make a dichotomous classification (i.e., formative vs. summative), doing so is not straightforward for empirical studies due to the contextual complexity. Hence, we used two more explicit indicators instead of arbitrarily classifying the purposes to be formative or summative. These two indicators included (1) whether self-assessment scores were used for learning improvement or account for students’ final grade; and (2) whether the self-assessment results were reported in qualitative (i.e., written comments, reflective notes) or quantitative approaches (i.e., marks, scores). There were eight studies (2, 3, 8, 14, 16, 27, 35, 40) found which incorporated self-assessment both for learning improvement and final grade. In addition, 6 studies (1, 4, 36, 37, 41, 42) included both qualitative and quantitative self-assessment. Surprisingly, only four studies explicitly discussed students’ opinions regarding self-assessment with different purposes. Most studies favoured self-assessment for learning improvement or those with qualitative methods. For example, students appreciated that self-assessment could improve their learning quality even if it did not necessarily result in better marks because the self-assessment process provided additional space and time to reflect on their own work (40). Students felt self-assessment with open-ended questions (qualitative approach) was more useful than those with rubrics (quantitative approach) (4). In contrast, self-assessment within a summative context appeared less useful in enhancing students’ learning quality because students focused too much on their marks (2)..

RQ4- What Factors Affect Students’ Implementation of Self-assessment?

A total of 21 studies have examined factors influencing the implementation of self-assessment in students’ perceptions (4, 5, 9, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 21, 23, 25, 28, 31, 33, 38, 39, 41, 42, 43, 44). These factors could be categorised into two groups, i.e., individual and instructional factors.

Individual Factors

Perceived Usefulness

The perceived usefulness of self-assessment refers to students’ perceptions about the effectiveness or consequences of performing self-assessment in their learning. A total of four studies examined its relationship with the implementation of self-assessment (5, 21, 38, 42). These studies have consistently shown that students’ motivation for and engagement in self-assessment were strongly influenced by the perception of its positive impact, such as identifying their strengths and weaknesses, monitoring their learning progress, and improving their learning confidence. Students who found self-assessment beneficial for their learning were willing to use it frequently and voluntarily (42). This finding applies to different subject areas, such as mathematics (21, 42) and writing (38). In addition to learning, students perceived self-assessment as a valuable capacity for their future careers (5).

Affective Attitude

The affective attitude towards self-assessment is about whether students like to implement it or not. This factor was investigated in two studies (38, 44). It should be noted that students’ affective attitude towards self-assessment is usually considered more a state than a trait, as it can change over time and is influenced by students’ self-assessment experiences. For example, Yan, Chiu et al. (2020) revealed that students initially liked the idea of self-assessment diaries, but their interest diminished gradually after completing three to four diaries (44). Students were happy to do self-assessment when their work was appreciated, while those who made more mistakes in their work disliked self-assessment and were unwilling to criticise in this way (38).

Self-efficacy

Self-assessment self-efficacy, referring to students’ confidence in their skills and abilities in conducting self-assessment successfully, was found relevant to self-assessment implementation in four studies (11, 18, 41, 43). Yan, Brown et al.'s (2020) study explicitly demonstrated that students with higher self-efficacy in self-assessment were more likely to conduct four self-assessment behaviours, including seeking external feedback through monitoring, seeking external feedback through inquiry, seeking internal feedback, and self-reflection (43). Additionally, the lack of confidence in using self-assessment is associated with lower self-assessment accuracy (18). However, high self-assessment self-efficacy does not necessarily lead to desirable outcomes. For example, students who felt they were skilful at self-assessment might overestimate their own performance more than others (11). Students’ self-efficacy in their learning also influences their self-assessment. For instance, Butler and Lee (2006) revealed that academic confidence influenced the off-task self-assessment (i.e., a general and decontextualised self-assessment on students’ overall performance) for 4th and 6th grade students (9).

Important Others

The pressure exerted by important individuals, i.e., how people who hold significance to students perceive self-assessment, can influence the implementation of self-assessment by the students. This finding was reiterated in four studies (4, 15, 31, 43). Yan, Brown et al. (2020) found that important others (they used the term “subjective norms” according to the Theory of Planned Behaviour) had a significant impact on students’ intentions to self-assess (43). Andrade and Du (2007) reported that it was confusing for students to self-assess when there was a clash between their own standards and teachers’ expectations (4). It is also possible that some students self-assess just to ensure teachers and parents can understand their perspectives, rather than for self-improvement (15). Furthermore, both school and student expectations could influence the accuracy of self-assessment. While students with high expectations for themselves might overestimate their performance, students in schools with a high level of expectations of students’ performance might underestimate themselves (31).

Psychological Safety

Psychological safety is about whether students feel psychologically safe in conducting self-assessment. This factor was discussed in 4 studies (5, 11, 15, 43). Psychological safety matters, especially occur when self-assessments involve interpersonal interactions (e.g., students are required to discuss their self-assessment results with peers). On the one hand, students are concerned about bias and inaccuracy associated with self-assessment (5). On the other hand, they were anxious about teachers’ negative responses if they gave honest (usually low) self-assessment results (15). Some students perceived self-assessment as a source of unnecessary pressure or stress for them; one of them said, “I do not think this should be done every time you do a surgical because it involves some kind of stress with it, being assessed, it’s just like an exam” (11). Yan, Brown et al. (2020) reported a positive relationship between students’ psychological safety and their self-assessment actions. The safer students feel about the learning environment, the more likely they implement self-assessment, such as seeking external feedback and internal feedback on their performance, and self-reflection (43).

Instructional Factors

Practice and Training

A total of eight studies (4, 11, 14, 16, 25, 39, 41, 42) reported practice and training on self-assessment as an important factor in determining students’ self-assessment. In students’ opinion, more practice is necessary for them to become confident in conducting self-assessment (41, 42). In particular, it is essential for students to understand the assessment procedure and assessment criteria before performing self-assessment (11). The absence of relevant experience or unfamiliarity with assessment standards makes self-assessment much more difficult for many students (14). Practice and training can significantly change students’ attitudes and behaviour regarding assessment. For example, in Andrade and Du’s (2007) study, before self-assessment practice, participants perceived themselves as unable to self-assess, placing a low value on themselves as a source of feedback. However, all the participants favoured self-assessment after extended practice (4). Wang (2017) reported that a student initially resisted self-assess. However, repeated self-assessment practices enhanced the student’s positive attitude and willingness to self-assess (39). Perera et al. (2010) found that, after training, more than 90% of students consistently or frequently did self-assessment, and approximately 85% of students expressed interest in self-assessment in future learning programs (25). After completing the self-assessment assignment, the percentage of students planning to perform the self-assessment increased from 23.1% to 91% (16).

External Feedback

External feedback in various forms from different sources is crucial for self-assessment, which was revealed in five studies (13, 15, 23, 28, 33). From the students’ perspective, it is a barrier for them to complete a self-assessment without formative feedback from their supervisors. Furthermore, they perceived peer feedback was beneficial for self-assessment (33). In addition, feedback from teachers also increased the accuracy of self-assessment (28). Compared to low achievers, high-achieving students preferred tutor feedback and were more likely to use it during self-assessment (23). Some students reported that it was helpful to view other students’ work as an example and receive feedback from their peers during self-assessment (15). E-feedback is also useful because it helps participants validate and modify their way of thinking when doing the self-assessment tasks (13).

Use of Instruments

Five studies (4, 31, 34, 39, 42) found that using instruments was another important facilitator for self-assessment. Students used self-assessment guidelines, checklists, and rubrics throughout the self-assessment process because these instruments helped them set goals, check work quality, guide revision, or reflect on the work (4, 39). The rubric was also perceived to be useful for developing self-monitoring habits and/or abilities when it was used to track the learning process (39, 42). Students believed rubrics helped them a lot in self-assessment because rubrics pinpointed important parameters in the assessment (34). Interestingly, Ross et al. (2002) found that girls intended to report rubrics more useful during their evaluation work than boys.

Environmental Support

Whether or not students perceive support from the learning environment also influences the implementation of self-assessment. This factor was gauged in four studies (4, 12, 16, 33). In Hill’s (2016) study, South African students reported being more willing to self-assess in an environment with incentives for self-assessment (i.e., 5% of the final marks was allocated for the self-assessment accuracy and the quality of the reflection) (16). Students also reported that competition with friends or other classes encouraged them to do more self-assessments (12). Sargeant et al. (2011) found that emotional support from peers plays a crucial role in implementing self-assessment (33). In Andrade and Du’s (2007) study, most students believed that their low motivation to carry out self-assessment was largely due to a lack of support in the class. (4).

Discussion

This review aimed to advance the understanding of students’ perceptions of self-assessment. In this section, the findings of 44 empirical studies were synthesised against four research questions and the implications of the findings are discussed.

RQ1- What are the Characteristics of Studies on Students’ Perceptions of Self-assessment?

Included studies have been primarily conducted in developed countries/regions, indicating more attention to student self-assessment in these countries/regions. The number of studies conducted in the context of higher education is much larger than in K-12. Although past studies tend to show that self-assessment accuracy increases with students’ age or academic ability (e.g., Brown & Harris, 2013; Topping, 2003), it does not mean that self-assessment is appropriate only at the developmental stage when students can make accurate self-assessment. This is because, theoretically, students can develop metacognition from engaging in self-assessment, regardless of accuracy (Panadero et al., 2016; Yan, 2022) and, empirically, self-assessment interventions in K-12 consistently demonstrate a positive impact (e.g., Bond & Ellis, 2013; Nikou & Economides, 2016). Furthermore, as self-assessment processes can be learned and optimised (Boud, 1995; Harris & Brown, 2018; Yan, 2022), sufficient training for students can increase self-assessment accuracy over time (Li & Zhang, 2020; Wong, 2016). Given the importance of self-assessment for student learning in K-12 contexts, and the fact that students’ perceptions about assessment influence their learning behaviours and the effects of assessment (Brown, 2011; Brown & Hirschfeld, 2008), more studies are needed to explore K-12 students’ perceptions of self-assessment and how to embed it into K-12 curriculum.

Researchers have utilised both quantitative (e.g., surveys) and qualitative (e.g., interviews, focus group interviews, worksheets, reflective journals) data collection methods to investigate students’ perceptions of self-assessment. Surveys are the most commonly employed method, likely due to their ability to expedite the data collection process when working with large sample sizes. However, more than 20% of survey studies (N = 6) included in this review had a small sample (less than 50), leaving their results likely unreliable and ungeneralisable.

Furthermore, the quality of the questionnaires used in survey studies is crucial as it influences the usefulness of the data collected. Unfortunately, there are no widely-used, standardised instruments assessing students’ perceptions of self-assessment. Most survey studies used ad-hoc questionnaires or modified questionnaires from previous studies without reporting reliability and validity information. Thus, it is almost impossible to meaningfully compare results from different studies.

In some studies, researchers included open-ended questions in the questionnaire survey to gather detailed information about students’ perceptions. With open-ended questions, students can reflect more deeply and freely on self-assessment without being bounded by standard answers (Wong, 2017). Nevertheless, the analysis of open-ended responses requires more time and effort.

Interview methods (both individual and focus group interviews) were also frequently used. Compared to surveys, interview methods allow researchers to gain more detailed and in-depth insights into students’ perceptions of self-assessment. Interview methods are especially useful for small sample sizes so that researchers can spend more time with participants and encourage them to speak more (Restrepo & Nelson, 2013). However, the shortcoming of interview methods is that the findings may not be generalisable due to the small sample size.

RQ2- How Do Students Perceive the Usefulness of Self-assessment?

There are inconclusive findings regarding students’ perceptions of the usefulness of self-assessment in facilitating their learning. Although most studies reported that students hold a generally positive perception of the usefulness of self-assessment (e.g., Evans et al., 2005; Hung, 2019), some studies found mixed results (e.g., Hanrahan & Isaacs, 2001; Lew et al., 2010), or even negative perceptions (e.g., Al-Kadri et al., 2012; Strobl, 2015). This finding is an interesting coincidence with the results of the meta-analysis on the effect of self-assessment on academic performance (Brown & Harris, 2013; Yan et al., 2022). Brown and Harris (2013) reviewed 22 studies and found that some self-assessment interventions had nil to small effects, although most studies reported positive effects. A more recent meta-analysis (Yan et al., 2022) found that, despite the overall positive effect of self-assessment, negative effects were observed in almost a quarter of self-assessment intervention studies in the meta-analysis. These findings, on the one hand, indicate that both the perceived and actual usefulness of self-assessment is promising among most students. On the other hand, the usefulness varies across samples and contexts. Hence, it is crucial to better understand possible factors influencing the usefulness of self-assessment. Such an understanding has the potential to inform the design of self-assessment and optimise its positive impact on learning.

RQ3- What Factors Affect Students’ Perceived Usefulness of Self-assessment?

The findings of the review showed that factors influencing students’ perceived usefulness of self-assessment include individual factors (i.e., age) and instructional factors (i.e., external feedback, use of instruments, self-assessment purpose). Older students tend to have a more positive attitude towards self-assessment than their younger counterparts (1, 6, 7). This is probably because older students have particular characteristics, such as higher academic abilities, better self-regulation skills, and more sophisticated self-assessment strategies, which might result in a stronger belief in self-assessment (Brown & Harris, 2013). External feedback, mainly from teachers, is a crucial factor in enacting the benefits of self-assessment (2, 6, 11, 12, 22, 31, 33, 40). Having external feedback in the self-assessment process makes learning expectations clear, enhances self-assessment accuracy, and helps students to identify areas where they need to devote more time. Whether the self-assessment is conducted with instruments is also vital for perceived usefulness. In students’ perceptions, using instruments made self-assessment easier and more useful to their learning (11, 34, 36, 39, 40, 42). Among various instruments, rubrics attract the most attention and are regarded as the most helpful, which is congruent with previous studies reporting that the use of specific and clearly-described criteria leads to more accurate and realistic self-assessment judgements (e.g., Brantmeier et al., 2012; Kostons et al., 2012). Regarding self-assessment purposes, past studies (e.g., Andrade, 2019) advocate the formative use of self-assessment for its advantage in providing improvement opportunities. Similarly, some included studies (e.g., 2, 4, 40) reported that students placed more value on self-assessment for learning improvement or with qualitative methods.

RQ4- What Factors Affect Students’ Implementation of Self-assessment?

Individuals’ perceptions of behaviour can determine whether or not an individual carries out the behaviour (Ajzen, 1991), especially when the behaviour, such as self-assessment, is largely under the individual’s control. Hence, it is vital to understand what factors influence the implementation of self-assessment from the student’s perspective. With such an understanding, teachers who intend to promote student self-assessment are aware of the support that needs to be provided and can develop appropriate instructional contexts to facilitate student self-assessment. This review showed that students perceived two groups of factors influencing their self-assessment implementation, i.e., individual and instructional factors.

Individual factors identified in this review include perceived usefulness (5, 21, 38, 42), affective attitude (38, 44), self-efficacy (11, 18, 41, 43), important others (4, 15, 31, 43), and psychological safety (5, 11, 15, 43). Students who possess a high level of perceived usefulness, positive affective attitude, and high self-efficacy, as well as feel pressure from important others are more likely to implement self-assessment. The important role of perceived usefulness, affective attitude, important others, and self-efficacy identified in this review is congruent with classic psychological frameworks (e.g., the Theory of Planned Behaviour, Ajzen, 1991) that link perceptions and behaviours. It also echoes previous studies (e.g., Mendoza et al., 2023; Yan, Brown et al., 2020) that emphasised the psychological mechanism determining students’ self-assessment behaviour. Psychological safety is also crucial, especially when self-assessments involve interpersonal interactions, such as seeking external feedback or disclosing the self-assessment results to others. The psychologically safe environment encourages students to be open and honest in self-assessment activities (Brown & Harris, 2013). In a safe learning environment, students are more likely to interpret self-assessment results, whether satisfying or not, as learning opportunities rather than summative evaluations (Yan, Brown et al., 2020). These findings indicate that students’ individual beliefs about self-assessment need to be considered in any attempt to enhance their engagement in self-assessment activities. Teachers can use various strategies to enhance students’ positive beliefs about self-assessment. For example, they can explicitly communicate the benefits of self-assessment to students and help them understand how it can support their learning and development. Additionally, teachers can provide students with opportunities to practice self-assessment under clear guidance in a safe and supportive environment to help them improve their self-assessment skills and self-efficacy.

In addition to individual factors, students also regard instructional factors (i.e., practice and training, external feedback, use of instruments, and environmental support) as crucial for their implementation of self-assessment. Practice and training were crucial due to their dual roles in influencing self-assessment. On the one hand, practice and training directly impact self-assessment. For example, relevant training or more experience in self-assessment can enhance students’ understanding of self-assessment criteria and familiarise them with the process, making self-assessment easier and more rewarding (11, 14). On the other hand, practice and training can indirectly impact self-assessment implementation by altering students’ attitudes towards (4, 39) or self-efficacy of self-assessment (41, 42). Scaffolds for self-assessment (e.g., external feedback and instruments) are important. External feedback matters in the self-assessment process because it helps clarify the learning expectations and increase the self-assessment quality (15, 28, 33). A purely introspective self-assessment process without external feedback, is vulnerable to idiosyncratic heuristics and bias (Joughin et al., 2019; Yan, 2022). To minimise the potential bias and maximise the desirable learning gains in the self-assessment process, students should be encouraged to seek and use external feedback to aid their self-assessment (Boud, 1999; Butler & Winne, 1995). Similarly, various instruments, such as guidelines, checklists, and rubrics, can facilitate self-assessment practices (4, 31, 34, 39, 42). This is likely because self-assessment instruments offer a framework of reference or an important comparator that enables generating useful internal feedback (Nicol, 2021). Apart from scaffolds for self-assessment, a supportive and psychologically safe learning environment is vital. The environmental support could be incentives for self-assessment (16), emotional support from peers (33), or a learning setting that values and encourages self-assessment (12). Overall, creating a supportive and encouraging learning environment is essential for students to better engage in self-assessment.

Implications for Future Self-assessment Studies

A significant challenge associated with research on students’ perceptions of self-assessment is the diverse implementations that are labelled under this concept, from purely summative practices to formative ones (see Panadero et al., 2016). Yan (2016) summarised that studies have operationally conceptualised self-assessment as an ability/skill for evaluating one’s own work, an assessment method, or a learning/instruction process. Even within the learning process perspective, which is dominant in current literature, researchers describe the self-assessment process in many different ways (Andrade, 2019; Panadero et al., 2016; Yan, 2022). A lack of consensus on conceptualising self-assessment makes it challenging to interpret and compare students’ perceptions in different contexts. To address this challenge, we encourage researchers to clearly define the type of self-assessment they are employing, as this facilitates interpretations of the results and replication of successful self-assessment designs. Some studies have done so fairly well, but others have not.

Another challenge is the lack of common theoretical frameworks that could guide the inclusion and organisation of factors relevant to students’ perceptions of self-assessment. Such a deficit results in fragmented information, rather than a holistic understanding, of students’ perceptions of self-assessment. Based on the findings of the current review, we proposed a model, as shown in Fig. 2, that covers frequently-studied factors related to student perceptions of self-assessment.

This model summarises influencing factors available in the literature, but it might not represent a comprehensive list of all possible factors when more studies in this field are emerging. The inclusion of both individual and instructional factors echoes the ecological perspective on class-based assessment (Chong & Isaacs, 2023). That is, self-assessment is a complex process happening in a dynamic learning environment. Students’ engagement in self-assessment is an outcome of alignment between students’ cognitive-psychological needs and learning contexts. Furthermore, an integrative approach should be adopted when investigating these factors, as there might be interactions within and across individual and instructional factors. For instance, training and practice (instructional factor) may enhance students’ positive attitudes towards and self-efficacy in self-assessment (individual factor). It is also possible that environmental support (instructional factor) influences students’ attitudes toward self-assessment and psychological safety (individual factor).

Limitations

There are several limitations in this review. First, although we used multiple key terms in the literature search, it is possible that we did not identify all relevant published literature. Perceptions have been studied in diversified terms and self-assessment consists of various forms, so it is difficult to include every relevant study. As students’ perceptions of self-assessment are often investigated together with other topics, some studies that treat this topic as a minor part of their research agenda may be missed in this review. Second, among all predictors that affect students’ implementation of self-assessment, the current review examined only one of them, i.e., the perceived usefulness of SA, in terms of its influencing factors. Thus, future studies could explore other predictors in detail in a similar way. A nuanced picture of each predictor will provide more insights into the design of personal scaffoldings and instructional settings for promoting meaningful self-assessment.

Conclusion

This review addressed two key aspects of students’ perceptions of self-assessment. First, it depicted students’ perceived usefulness of self-assessment and its influencing factors. Second, it identified two groups of factors (i.e., individual and instructional factors) that affect students’ implementation of self-assessment. This review contributed to a nuanced understanding of students’ perceptions of self-assessment. Since self-assessment is a student-directed process, such an understanding can not only help increase students’ engagement in self-assessment, but also inform the design of self-assessment activities to maximise its positive impact on learning.

References

References marked with an asterisk indicate studies included in the review

*Adediwura, A. A. (2012). Effect of peer and self-assessment on male and female students’ self-efficacy and self-autonomy in the learning of mathematics. Gender and Behaviour, 10(1), 4492-4508.

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organisational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211.

*Al-Kadri, H., Al-Moamary, M. S., Al-Takroni, H., Roberts, C., & van der Vleuten, C. P. (2012). Self-assessment and students’ study strategies in a community of clinical practice: A qualitative study. Medical Education Online, 17(1), 11204.

*Allen, D. D., & Flippo, R. F. (2002). Alternative assessment in the preparation of literacy educators: Responses from students. Reading Psychology, 23(1), 15-26.

Andrade, H. L. (2019). A critical review of research on student self-assessment. Frontiers in Education, 4. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2019.00087

*Andrade, H., & Du, Y. (2007). Student responses to criteria-referenced self-assessment. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 32(2), 159–181.

*Babu, A., & Barghathi, Y. (2020). Self-assessment and peer assessment in accounting education: Students and lecturers perceptions. Corporate Ownership and Control, 17(4), 353-368.

*Bakx, A. W., Sijtsma, K., Van der Sanden, J. M., & Taconis, R. (2002). Development and evaluation of a student-centred multimedia self-assessment instrument for social-communicative competence. Instructional Science, 30, 335-359.

Bonner, S. M. (2016). Teachers’ perceptions about assessment: Competing narratives. In G. Brown & L. Harris (Eds.), Handbook of human and social conditions in assessment (pp. 21–39). Routledge.

Bond, J. B., & Ellis, A. K. (2013). The effects of metacognitive reflective assessment on fifth and sixth graders’ mathematics achievement. School Science and Mathematics, 113(5), 227–234.

Boud, D. (1995). Enhancing learning through self-assessment. Routledge.

Boud, D. (1999). Avoiding the traps: Seeking good practice in the use of self-assessment and reflection in professional courses. Social Work Education, 18(2), 121–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479911220131

Bourke, R. (2014). Self-assessment in professional programmes within tertiary institutions. Teaching in Higher Education, 19(8), 908–918.

*Bourke, R. (2016). Liberating the learner through self-assessment. Cambridge Journal of Education, 46(1), 97-111.

Brantmeier, C., Vanderplank, R., & Strube, M. (2012). What about me? Individual self-assessment by skill and level of language instruction. System, 40, 144–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2012.01.003

*Brookhart, S. M. (2001). Successful students’ formative and summative uses of assessment information. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 8(2), 153-169.

Brown, G. (2011). Self-regulation of assessment beliefs and attitudes: A review of the Students’ Conceptions of Assessment inventory. Educational Psychology, 31(6), 731–748.

Brown, G. T. L., & Harris, L. R. (2013). Student self-assessment. In J. H. McMillan (Ed.), The SAGE handbook of research on classroom assessment (pp. 367–393). Sage.

Brown, G. T. L., & Wang, Z. (2013). Illustrating assessment: How Hong Kong university students conceive of the purposes of assessment. Studies in Higher Education, 38(7), 1037–1057. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2011.616955

Brown, G. T., & Hirschfeld, G. H. (2008). Students’ conceptions of assessment: Links to outcomes. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 15(1), 3–17.

*Butler, Y. G., & Lee, J. (2006). On‐task versus off‐task self‐assessments among Korean elementary school students studying English. The Modern Language Journal, 90(4), 506-518.

Butler, D. L., & Winne, P. H. (1995). Feedback and self-regulated learning: A theoretical synthesis. Review of Educational Research, 65(3), 245–281. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543065003245

Cho, H. J., Yough, M., & Levesque-Bristol, C. (2020). Relationships between beliefs about assessment and self-regulated learning in second language learning. International Journal of Educational Research, 99, 101505.

Chong, S. W., & Isaacs, T. (2023). An Ecological Perspective on Classroom-Based Assessment. TESOL Quarterly. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.3201

*Duque Micán, A., & Cuesta Medina, L. (2017). Boosting vocabulary learning through self-assessment in an English language teaching context. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 42(3), 398–414.

*Evans*, A. W., McKenna, C., & Oliver, M. (2005). Trainees’ perspectives on the assessment and self‐assessment of surgical skills. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 30(2), 163-174.

*Gashi-Shatri, Z. F., & Zabeli, N. (2018). Perceptions of students and teachers about the forms and student self-assessment activities in the classroom during the formative assessment. Journal of Social Studies Education Research, 9(2), 28-46.

Gjicali, K., & Lipnevich, A. A. (2021). Got math attitude?(In) direct effects of student mathematics attitudes on intentions, behavioral engagement, and mathematics performance in the US PISA. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 67, 102019.

*Handley, K., & Cox, B. (2007). Beyond model answers: Learners’ perceptions of self-assessment materials in e-learning applications. ALT-J, 15(1), 21-36.

*Hanrahan, S. J., & Isaacs, G. (2001). Assessing self-and peer-assessment: The students’ views. Higher Education Research & Development, 20(1), 53-70.

*Harris, L. R., & Brown, G. T. (2013). Opportunities and obstacles to consider when using peer-and self-assessment to improve student learning: Case studies into teachers’ implementation. Teaching and Teacher Education, 36, 101-111.

Harris, L. R., & Brown, G. T. L. (2018). Using self-assessment to improve student learning. Routledge.

*Hill, T. (2016). Do accounting students believe in self-assessment?. Accounting Education, 25(4), 291-305.

*Hung, Y. J. (2019). Bridging assessment and achievement: Repeated practice of self-assessment in college english classes in Taiwan. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 44(8), 1191-1208.

*Irani, T., & Telg, R. (2002). Gauging distance education students’ comfort level with technology and perceptions of self-assessment and technology training initiatives. Journal of Applied Communications, 86(2), 45-55.

Joughin, G., Boud, D., & Dawson, P. (2019). Threats to student evaluative judgement and their management. Higher Education Research & Development, 38(3), 537–549.

Kostons, D., Van Gog, T., & Paas, F. (2012). Training self-assessment and task-selection skills: A cognitive approach to improving self-regulated learning. Learning and Instruction, 22(2), 121–132.

*Lau, P. N. (2020). Enhancing formative and self-assessment with video playback to improve critique skills in a titration laboratory. Chemistry Education Research and Practice, 21(1), 178-188.

*Lew, M. D., Alwis, W. A. M., & Schmidt, H. G. (2010). Accuracy of students’ self‐assessment and their beliefs about its utility. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 35(2), 135-156.

Li, M., & Zhang, X. (2020). A meta-analysis of self-assessment and language performance in language testing and assessment. Language Testing, 38(2), 189–218.

*Logan, B. (2015). Reviewing the value of self-assessments: Do they matter in the classroom? Research in Higher Education Journal, 29, 1-11.

Mendoza, N. B., Yan, Z., & King, R. B. (2023). Supporting students’ intrinsic motivation for online learning tasks: The effect of need-supportive task instructions on motivation, self-assessment, and task performance. Computers & Education, 193, 104663.

*Ndoye, A. (2017). Peer/Self Assessment and Student Learning. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 29(2), 255-269.

Nicol, D. (2021). The power of internal feedback: Exploiting natural comparison processes. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 46(5), 756–778. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2020.1823314

Nikou, S. A., & Economides, A. A. (2016). The impact of paper-based, computer-based and mobile-based self-assessment on students’ science motivation and achievement. Computers in Human Behavior, 55, 1241–1248.

*Orsmond, P., & Merry, S. (2013). The importance of self-assessment in students’ use of tutors’ feedback: A qualitative study of high and non-high achieving biology undergraduates. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 38(6), 737-753.

*Orsmond, P., Merry, S., & Reiling, K. (1997). A study in self‐assessment: tutor and students’ perceptions of performance criteria. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 22(4), 357-368.

Panadero, E., Brown, G. T., & Strijbos, J. W. (2016). The future of student self-assessment: A review of known unknowns and potential directions. Educational Psychology Review, 28(4), 803–830.

Panadero, E., Lipnevich, A. A., & Broadbent, J. (2019). Turning self-assessment into self-feedback. In D. Boud, M. D. Henderson, R. Ajjawi, & E. Molloy (Eds.), The Impact of Feedback in Higher Education: Improving Assessment Outcomes for Learners (pp. 147–163). Springer.

Panadero, E., Jonsson, A., & Botella, J. (2017). Effects of self-assessment on self-regulated learning and self-efficacy: Four meta-analyses. Educational Research Review, 22, 74–98.

*Perera, J., Mohamadou, G., & Kaur, S. (2010). The use of objective structured self-assessment and peer-feedback (OSSP) for learning communication skills: evaluation using a controlled trial. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 15, 185-193.

Petticrew, M., & Roberts, H. (2006). Systematic reviews in the social sciences: A practical guide. Blackwell Publishing.

*Pidduck, T. M., & Bauer, N. (2021). Perceptions of online self-and peer-assessment: accounting students in a large undergraduate cohort. Journal of Applied Research in Higher Education, 14(4), 1480–1495.

*Ramirez, B. U. (2010). Effect of self-assessment on test scores: student perceptions. Advances in Physiology Education, 34(3), 134–136.

*Rees, C., & Shepherd, M. (2005). Students’ and assessors’ attitudes towards students’ self‐assessment of their personal and professional behaviours. Medical education, 39(1), 30-39.

*Restrepo, A., & Nelson, H. (2013). Role of Systematic Formative Assessment on Students’ Views of Their Learnin. Profile Issues in TeachersProfessional Development, 15(2), 165-183.

*Ross, J. A., Rolheiser, C., & Hogaboam-Gray, A. (1998). Skills training versus action research in-service: Impact on student attitudes to self-evaluation. Teaching and Teacher Education, 14(5), 463-477.

*Ross, J. A., Rolheiser, C., & Hogaboam-Gray, A. (2002). Influences on student cognitions about evaluation. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 9(1), 81-95.

*Sadeghi, K., & Abolfazli Khonbi, Z. (2015). Iranian university students’ experiences of and attitudes towards alternatives in assessment. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 40(5), 641-665.

*Sargeant, J., Eva, K. W., Armson, H., Chesluk, B., Dornan, T., Holmboe, E., & van der Vleuten, C. P. (2011). Features of assessment learners use to make informed self-assessments of clinical performance. Medical Education, 45(6), 636–647.

*Seifert, T., & Feliks, O. (2019). Online self-assessment and peer-assessment as a tool to enhance student-teachers’ assessment skills. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 44(2), 169-185.

*Sieber, V. (2009). Diagnostic online assessment of basic IT skills in 1st‐year undergraduates in the Medical Sciences Division, University of Oxford. British Journal of Educational Technology, 40(2), 215-226.

Siow, L. F. (2015). Students’ Perceptions on Self-and Peer-Assessment in Enhancing Learning Experience. Malaysian Online Journal of Educational Sciences, 3(2), 21–35.

Sitzmann, T., Ely, K., Brown, K. G., & Bauer, K. N. (2010). Self-assessment of knowledge: A cognitive learning or affective measure? Academy of Management Learning & Education, 9(2), 169–191.

*Strobl, C. (2015). Attitudes towards online feedback on writing: Why students mistrust the learning potential of models. ReCALL, 27(3), 340-357.

*Sullivan, K., & Hall, C. (1997). Introducing students to self‐assessment. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 22(3), 289-305.

*Tavsanli, Ö. F., & Kara, Ü. E. (2021). The effect of a peer and self-assessment-based editorial study on students’ ability to follow spelling rules and use punctuation marks correctly. Participatory Educational Research, 8(3), 268-284.

Topping, K. (2003). Self and peer assessment in school and university: Reliability, validity and utility. In M. Segers, F. Dochy, & E. Cascallar (Eds.), Optimising new modes of assessment: In search of qualities and standards (pp. 55–87). Kluwer Academic Publisher.

van der Kleij, F. M., & Lipnevich, A. A. (2021). Student perceptions of assessment feedback: A critical scoping review and call for research. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability, 33, 345–373.

van Helvoort, A. J. (2012). How adult students in information studies use a scoring rubric for the development of their information literacy skills. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 38(3), 165–171.

*Wang, W. (2017). Using rubrics in student self-assessment: student perceptions in the English as a foreign language writing context. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 42(8), 1280-1292.

*Wanner, T., & Palmer, E. (2018). Formative self-and peer assessment for improved student learning: the crucial factors of design, teacher participation and feedback. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 43(7), 1032-1047.

Wolffensperger, Y., & Patkin, D. (2013). Self-assessment of self-assessment in a process of co-teaching. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 38(1), 16–33.

*Wong, H. M. (2016). I can assess myself: Singaporean primary students’ and teachers’ perceptions of students’ self-assessment ability. Education 3–13, 44(4), 442–457.

*Wong, H. M. (2017). Implementing self-assessment in Singapore primary schools: Effects on students’ perceptions of self-assessment. Pedagogies: An International Journal, 12(4), 391–409.

Yan, Z. (2016). The self-assessment practices of Hong Kong secondary students: Findings with a new instrument. Journal of Applied Measurement, 17(3), 335–353.

Zhan, Y., Yan, Z., Wan, Z. H., Wang, X., Zeng, Y., Yang, M., & Yang, L. (2023). Effects of online peer assessment on higher-order thinking: A meta-analysis. British Journal of Educational Technology, 54(4), 817–835. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.13310

Yan, Z. (2022). Student self-assessment as a process for learning. Routledge.

Yan, Z., & Brown, G. T. L. (2017). A cyclical self-assessment process: Towards a model of how students engage in self-assessment. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 42(8), 1247–1262. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2016.1260091

*Yan, Z., Brown, G. T. L., Lee, C. K. J., & Qiu, X. L. (2020). Student self-assessment: Why do they do it? Educational Psychology, 40(4), 509–532. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2019.1672038

*Yan, Z., Chiu, M. M., & Ko, P. Y. (2020). Effects of self-assessment diaries on academic achievement, self-regulation, and motivation. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 27(5), 562–583. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969594X.2020.1827221

Yan, Z., Lao, H., Panadero, E., Fernández-Castilla, B., Yang, L., & Yang, M. (2022). Effects of self-assessment and peer-assessment interventions on academic performance: A meta-analysis. Educational Research Review, 37, 100484. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2022.100484

Zekarias, A. P. (2023). Contributions and controversies of self-assessment to the development of writing skill. Journal of Research in Instructional, 3(1), 13–30.

Acknowledgements

The first author was supported by a General Research Fund from the Research Grants Council of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China (Project No. EDUHK 18609321).

The second author was funded by contribution of the Basque Government (Ref. IT1624-22) to the group Education Regulated Learning and Assessment.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yan, Z., Panadero, E., Wang, X. et al. A Systematic Review on Students’ Perceptions of Self-Assessment: Usefulness and Factors Influencing Implementation. Educ Psychol Rev 35, 81 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-023-09799-1

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-023-09799-1