Abstract

In this review, we examine studies of writing self-efficacy conducted with postsecondary students published between 1984 and 2021. We aimed to inventory the methodological choices, writing contexts, and types of pedagogies explored in studies of writing self-efficacy with postsecondary students, and summarize the practical implications noted across the included studies. A total of 50 studies met eligibility criteria. All studies used quantitative methods, were conducted in English language settings, focused on undergraduate or graduate students, and included at least one writing self-efficacy measure. Across the 50 studies, the two variables most commonly appearing alongside writing self-efficacy were writing performance and writing apprehension. Many studies also assessed change in writing self-efficacy over time. Writing contexts and measures of writing self-efficacy varied across the included studies. Common practical implications noted across studies included students’ tendency to overinflate their writing self-efficacy, recognition of the developmental nature of writing ability, the importance of teacher attitudes and instructional climate, the influence of feedback on writing self-efficacy, and approaches to teaching and guiding writing. Based on this review, we see several directions for future research including a need for longitudinal studies, consideration of situated approaches, identification of diversity impacts, and attention to consistent use of strong multidimensional measures of writing self-efficacy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

From admission essays to term papers and dissertations, writing can play a critical role in students’ success throughout college and graduate school. Writing helps students learn how to write and think about ideas in a substantive area (Ekholm et al., 2015; Golembek et al., 2018; Miller et al., 2015; Mitchell et al., 2019; Vanhille et al., 2017), communicate at the level required for success in a professional role (Jones, 2008; Plakhotnik & Rocco, 2016; Stewart et al., 2015; Van Blankenstein et al., 2019), and become a member of a discipline (Jonas & Hall, 2022; Mitchell & McMillan, 2018; Mitchell et al., 2021).

Writing as an activity is both cognitive and social (MacArthur et al., 2015; Mitchell et al., 2021). There is also a growing recognition of how affective factors influence academic writing ability (Dowd et al., 2019; Jonas & Hall, 2022; Vanhille et al., 2017). In combination, the cognitive, social, and affective impacts on writing mean that success requires attention to all three domains: (1) metacognition and knowledge of the tasks and skills required to write; (2) knowledge of contextual factors that might influence how writing may be perceived by an audience and how good writing is defined (e.g., disciplinary norms, audience awareness, and teacher biases); and (3) self-awareness of many personal affective factors, such as degree of interest in what one is writing about, whether one likes or dislikes writing as an activity, and ability to overcome negative emotions when the challenges exceed personal thresholds (MacArthur et al., 2015; Mitchell et al., 2021; Plakhotnik & Rocco, 2016; Van Blankenstein et al., 2019). As a complex and often challenging process, writing requires that learners be motivated to write. In particular, writing self-efficacy, defined as a learner’s beliefs about their ability to write (Schunk & Swartz, 1993), is a key component of writing success (Schunk & Zimmerman, 2007; Zimmerman & Bandura, 1994).

Self-efficacy is critically aligned with Bandura’s (1986) social cognitive framework and the model of triadic reciprocality, which posits that learning is reliant on reciprocal interactions between learners’ thoughts, behaviors, and environment. From this view, writing self-efficacy beliefs play an important role in learners’ perseverance, academic choices, and performance (Mitchell et al. 2019; Pajares et al., 2006). In postsecondary settings, for example, writing self-efficacy can influence student program completion, academic identity, and emotional well-being (Jonas & Hall, 2022). Likewise, social and contextual aspects, such as feedback and instructional conditions, can influence students’ writing efficacy beliefs (Bruning & Kauffman, 2016; Mitchell et al., 2019; Schunk & Swartz, 1993).

Drawing from this theoretical premise, several reviews have synthesized writing self-efficacy research, though with an almost exclusive focus on K-12 populations (e.g., Camacho et al., 2021; Klassen, 2002; Pajares, 2003; Zumbrunn & Bruning, in press). In an early systematic review of the role of self-efficacy beliefs in early adolescence (6th to 10th grade), Klassen (2002) found that self-efficacy positively predicted student writing performance. Pajares (2003) noted similar findings in his narrative review, citing a positive relation between writing self-efficacy and writing performance, even after controlling for prior achievement, gender, grade level, and other motivational variables. Writing self-efficacy beliefs remained a primary predictor of writing success in more recent reviews of writing motivation (Bruning & Kauffman, 2016; Camacho et al., 2021; Zumbrunn & Bruning, in press).

Across these reviews, however, authors expressed concerns about the measurement of writing self-efficacy. For example, Klassen (2002) called into question the rigor and validity of the writing self-efficacy measures used in the 16 studies reviewed. In some cases, he reported that the tools measured motivation constructs not directly aligned with writing self-efficacy. Similarly, Camacho et al. (2021) and Zumbrunn & Bruning, in press) found that several studies lacked a clear definition or operationalization of writing self-efficacy, hampering meaningful measurement.

Considering the measurement concerns consistently raised across reviews, it is not surprising that measurement was the target of the only review to date exploring writing self-efficacy research conducted in higher education settings (Mitchell et al., 2017c). In their systematic review, Mitchell and colleagues (2017) identified that researchers of postsecondary populations gravitate to different writing self-efficacy instruments than those identified as commonly used in K-12 populations (e.g., Zumbrunn & Bruning, in press). Two primary theoretical frameworks—self-efficacy theory (Bandura, 1997) and the cognitive processing model of writing developed by Flower and Hayes—guided their template analysis of the items across eleven different scales of writing self-efficacy. Findings from this review suggest that writing self-efficacy measures developed for undergraduate students emphasize the cognitive aspects of writing self-efficacy. Mitchell et al. (2017c) concluded that such a cognitive emphasis hinders theoretical and empirical understanding of the contextual aspects of writing self-efficacy, including creativity allowances, writing identity, and disciplinary discourse factors.

To build upon prior work and in consideration of the observations made in previous reviews of writing self-efficacy, we argue that a synthesis of the variability in writing self-efficacy research conducted in postsecondary settings is both timely and warranted. The complexity and importance of the writing process is well-aligned with the top ten skills of 2025 identified by the World Economic Forum in the Future Jobs Report (Forum, 2018). Although it stands to reason that the positive relationship between writing self-efficacy beliefs and writing success present across reviews of research conducted in K-12 settings (e.g., Camacho et al., 2021; Zumbrunn & Bruning, in press) is also present in adult learning settings (e.g., Ekholm et al., 2015; Mitchell et al., 2019), such a review does not exist. Our first aim of this work was therefore to explore the correlates and outcomes of writing self-efficacy in postsecondary research, as well as trends related to changes in writing self-efficacy over time.

With our second aim, and in line with social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1986), we intentionally focus on context to help situate postsecondary writing self-efficacy research by exploring potential environmental aspects at play. Specifically, we examined the nature of the writing instruction across studies of writing self-efficacy, such as discipline, year of study, and setting (e.g., writing center). As researchers and practitioners alike are keen to understand and find ways to enhance student writing self-efficacy, our analysis highlighted the pedagogical aspects of intervention studies.

The ability to understand student writing self-efficacy and effectively test changes over time hinges on clear and theoretically aligned conceptualization, operationalization, and measurement (Camacho et al., 2021; Zumbrunn & Bruning, in press). Given the longstanding concerns related to assessing self-efficacy noted not only in the writing self-efficacy reviews described earlier, but also in recent general reviews of self-efficacy (e.g., Schunk & DiBenedetto, 2020), the third aim of our work was to build upon the analysis reported in Mitchell et al. (2017c) and examine the measures of writing self-efficacy developed for postsecondary contexts. Taken together, findings related to aims 1–3 will highlight important trends in the literature to inform methodological approaches for future writing self-efficacy research.

As classroom instructors ourselves, it is important to note that we approached this work with a practical lens. Our fourth and final aim was therefore to synthesize the practical implications identified in studies of writing self-efficacy in postsecondary research in an effort to provide potential directions for future writing instruction and research on this instruction in postsecondary settings. Given the particularly exploratory nature of this aim, as well as the wide variety of settings, designs, and methodological choices across studies of writing self-efficacy with adult learners, we chose to conduct a scoping review.

Described as primarily descriptive and exploratory, scoping reviews are a systematic method to assess the breadth of coverage of the literature. These unique reviews focus on identifying key concepts, theories, and sources of evidence, explore gaps in the literature, and are particularly useful when aiming to map current progress in a research field (Peters et al., 2017, 2020).

Aligned with our aims, the following research questions guided this review:

-

1.

What associated variables appear alongside writing self-efficacy in research conducted on postsecondary students, and how does writing self-efficacy change over time?

-

2.

What is the nature of writing contexts in studies of writing self-efficacy, including the environment for writing, pedagogical strategies, and interventions tested?

-

3.

What trends emerge about writing self-efficacy measurement within this body of research?

-

4.

What have writing self-efficacy researchers identified as their implications for writing pedagogy based on their research findings?

Method

We employed Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) scoping review methods (Peters et al., 2017, 2020). Although not required by this methodology, we conducted a quality appraisal of the studies included not only because of the quantitative nature of the studies included in this review, but also because of our goal to synthesize the practical implications identified by researchers of included studies. Indeed, the soundness of a study’s practical implications is reliant on the soundness of the study’s quality of research.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Several criteria guided this review. The focus on academic writing in a postsecondary context meant, reflective writing, blog writing, and creative writing contexts was excluded. Studies exploring the writing self-efficacy levels of elementary, middle-school, or high-school students were excluded as were studies that focused on contexts of second-language writers learning English as a foreign language or contexts where the language the students were writing in was not English. All included studies used quantitative methodologies (e.g., experimental, quasi-experimental, descriptive cross-sectional, correlational, and psychometric methods). Qualitative studies were excluded, but the quantitative findings of mixed methods studies were included. All included studies employed the use of a self-efficacy measure specific to writing. Studies that used a general academic self-efficacy measure in a writing context or that measured beliefs about writing without asking students to rate their confidence and competence in writing were excluded. For pragmatic reasons, and due to lack of translation resources, only papers published in English were included. Similarly, dissertations were included as the focus of the grey literature search; however, dissertations that required a fee to download were not included. All efforts were made to locate a free copy of paid dissertations by contacting the authors.

Search Strategy

The search strategy aimed to find both published studies and available dissertations conducted from January 1, 1984 to January 30, 2021. The start date for the search corresponds with the date of the oldest study using an instrument developed specifically for measuring writing self-efficacy (Meier et al., 1984) as identified in Mitchell et al. (2017c). An initial limited search of Education Resources Information Center (ERIC) and Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) was undertaken followed by analysis of the text words contained in the title, abstract, and the indexed subject terms. This preliminary search informed the development of a search strategy which was tailored for each database by the librarian member of the team and peer-reviewed by a second librarian. The databases searched included CINAHL (Elton B. Stephens Company (EBSCO)), ERIC (ProQuest), PsychINFO (Ovid), Scopus (Elsevier), and MEDLINE (Ovid). A full search strategy for ERIC is detailed in Table 1. Google Scholar was also searched in order to capture unindexed sources and other sources outside of these key databases. A search for unpublished dissertations and theses was conducted in the ProQuest Dissertations & Theses database, Theses Canada, and MSpace, the University of Manitoba institutional repository. Additionally, the bibliographies and reference lists of the selected studies were searched to be certain all relevant studies were included and automated search alerts were created in the databases. The final search was conducted in January 2021.

Data Analysis

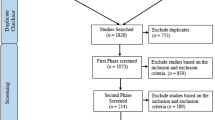

All titles and abstracts from the database searches were uploaded into the Covidence Review system (https://www.covidence.org/), and duplicates were removed. Two independent reviewers screened the titles and abstracts of 2255 papers, with 257 of those moving forward to full-text analysis. Wherever disagreement occurred between reviewers, a paper was moved to a conflicts folder in Covidence. The conflicts were then resolved with discussion and a third vote on the paper, resulting in review conditions where 100% agreement between reviewers was achieved. At the title and abstract phase of the review, decisions always erred on the side of including all papers where it was not fully clear if the paper met the inclusion criteria so it could undergo a more thorough screen at the full-text stage. In many cases, this was necessary because it was unclear in the abstract the exact methods of the paper or if writing self-efficacy was measured. In addition to the search strategy, eight papers were identified via sources outside the database search: two via reference lists of published studies, three via Google, and two authored by an author of this review (one in an unindexed source and the second that reached publication shortly after the completion of the final search).

Full-text studies of the relevant abstracts were initially independently screened by the first author. The second author was consulted when uncertainties arose about the inclusion or exclusion of specific studies and correctness of content in the data extraction. Each full text was reviewed a minimum of three times. First, all studies chosen as needing full-text examinations underwent an initial scan to look for major exclusion criteria that were not clearly stated within the paper’s abstract. Papers most commonly excluded during this screening phase included studies with excluded populations (e.g., K-12, foreign language learning) or methods (e.g., qualitative studies or discussion papers), missing measures (i.e., writing self-efficacy), and examining writing self-efficacy in a writing genre that was not academic writing (e.g., media, blogs, or reflective assignments). Second, all remaining papers and dissertations were read in full highlighting and annotating for the data of interest to the study. The papers were then read a third time during the completion of the data extraction table (see Supplemental Files 1 and 2). Initially, 61 articles and dissertations underwent data extraction and five were eliminated during this phase during consultations between the first and second author most commonly due to unrecognized non-English-speaking contexts in papers written in the English language. An additional six papers were eliminated after quality appraisal was initiated as described below. Those six eliminated papers are marked in Supplemental File 1.

In total after quality appraisal, we included 54 articles and dissertations that met the inclusion criteria, representing 50 unique studies. In two cases, two publications (a dissertation and a journal article) represented the same study, another case represented a publication and a report of the same study, and the final case represented two separate papers exploring different aspects of the same data. Of the 50 identified unique studies, 8 (16%) were only available as dissertations. Figure 1 presents a PRISMA diagram outlining article selection and the most common reasons for article exclusion.

Data was extracted from papers using a researcher-developed data extraction table (see Supplemental Files 1, 2, and 3 for data extraction tables). Extracted data included the itemized criteria of the framework depicted in Table 2: details of study methods, sample characteristics, the writing self-efficacy measure used, associated variables and their measures, theoretical frameworks, definitions of writing self-efficacy key study findings, writing environment consisting of course content or instructional strategies, performance outcome measure and processes of scoring writing performance, a description of the writing activities performed by the participants if performance was an outcome measure, and implications for pedagogy discussed by the authors of each study. The extracted data was coded to establish the frequencies of particular characteristics of the included papers (see Table 2), and SPSS (version 25) was used to calculate the descriptive statistics for research questions 1 through 3. Research question 4 was analyzed through narrative analysis methods, which synthesized into several categories the implications for writing pedagogy. The implications for pedagogy were identified by the researchers of the papers based on their study findings and were written about in the discussion and conclusion sections of their published papers and dissertations.

Study Quality

To index study quality, we adapted quality criteria for experimental/quasi-experimental (Gersten et al., 2005) and correlational (Thompson et al., 2005) methodologies (see Supplemental File 4 for a more detailed discussion of the quality coding procedures). We scored each criterion on a scale of 0 (criterion not addressed) to 2 (criterion fully addressed) and then summed the scores to assign an overall quality score to each article. If information for the criterion was not present, we assumed that the criterion was not met. Because the number of quality criteria differed for each methodology, we calculated the percentage of possible points each article earned and used this percentage score as our quality threshold. Studies earning less than 50% of the possible quality points were excluded from further analysis.

One coder analyzed the quality of all articles. Then, to establish reliability, an additional coder analyzed the quality of half of the studies (randomly selected). Agreement between the two coders was 93%.

Of the 56 primary studies that we evaluated for quality, 50 met or surpassed our quality threshold for inclusion into the review. Although we converted the quality score for each study into the percentage earned of the total possible points, the quality indicators used for each methodology (i.e., true/quasi experimental, correlational) are categorically different from one another. Therefore, we refrain here from making cross-method comparisons regarding quality of studies, since such comparisons would be somewhat arbitrary. For each methodology, we present the two quality indicators that studies earned the lowest percentage of available points on.

For each of these indicators, we present the percentage earned of possible points by all studies employing that methodology in parentheses. The indicators that experimental/quasi-experimental studies earned the fewest points on were “fidelity of implementation clearly described and assessed” (18%) and “sufficient information given to characterize interventionists or teachers, particularly whether they were comparable across conditions” (25%). The indicators that correlational studies earned the fewest points on were “authors interpret study effect sizes by directly and explicitly comparing study effects with those reported in related prior studies” (44%) and “score reliability coefficients reported and interpreted for all measured variables” (63%).

Results

Here, we present a summary of the characteristics of included studies, as well as findings related to each research question: (a) variables associated with writing self-efficacy with a focus on writing performance, writing apprehension and anxiety, change in writing self-efficacy over time; (b) descriptions of the writing contexts where the studies were conducted including pedagogies used and interventions; (c) trends in measurement of writing self-efficacy; and (d) the narrative analysis of implications for writing pedagogy.

General Characteristics of Included Studies

Table 2 summarizes the characteristics of the included studies.

Years

More than half (56%) of the included papers were published in the 7-year period between January 2014 and January 2021, indicating the explosion of interest in writing self-efficacy research since 1984.

Countries

Writing self-efficacy research in English language postsecondary contexts is a North American research interest with 92% of included studies originating from either the USA (76%) or Canada (16%).

Research Designs

Most studies employed either cross-sectional (34%) or pretest/posttest (28%) methods in their designs. These two designs were the only design choices in the first 20 years of writing self-efficacy research from 1984 to 2003 (10 papers—20% of all studies) except for a lone interventional study published in 2002 (Zimmerman & Kitsantas, 2002). Following the publication of this study, use of interventional and longitudinal methods remained infrequent with only a quarter of all included studies employing these methods (13 papers—26%). Development of statistical models such as structural equation modeling and path analysis was also less frequent (7 papers—14%).

Definitional Clarity and Theoretical Frameworks

We also explored the nature of how writing self-efficacy was defined and the theoretical frameworks guiding each of the studies (see Supplemental File 3 for definitions of writing self-efficacy, theoretical framework identification, and operationalization of writing self-efficacy). We followed a similar coding scheme to that described in Murphy and Alexander (2000) noting when writing self-efficacy was explicitly defined, implicitly defined, or not defined at all. All studies referenced Bandura’s seminal work by citation. Writing self-efficacy was explicitly defined in 17 of the included studies (34%). Of these 17 papers, 7 defined writing self-efficacy by adding the word “writing” somewhere into Bandura’s generic definition of self-efficacy. The majority of the papers (28–56%) implicitly defined writing self-efficacy through choices made in operationalizing the concept through measurement; however, these studies did include a general definition of self-efficacy. In five studies (10%), neither self-efficacy or writing self-efficacy were explicitly or implicitly defined.

Exploring Variables Associated with Writing Self-Efficacy

Research question 1 asked: What associated variables appear alongside writing self-efficacy in research conducted on postsecondary students, and how does writing self-efficacy change over time? Common variables that appear alongside writing self-efficacy in postsecondary research are listed by frequency in Table 2. In some studies, these aligned variables were the main variable of interest and writing self-efficacy was of secondary interest. Table 3 defines each of the categories of variables that appear alongside writing self-efficacy in studies and lists examples of common methods of operationalizing each variable. A brief description of the current evidence with respect to the relationship between the variable and writing self-efficacy is also included in the table.

To be included in the table, a variable had to have appeared alongside writing self-efficacy in at least four studies. Many variables that appeared less than four times should be noted. Several of these variables started appearing in more recent research and have encouraging evidence for exploration in future research including metacognition (Stewart et al., 2015), emotional intelligence (Huerta et al., 2017), use of prewriting to plan a timed essay (Vanhille et al., 2017), word counts of essays produced (MacArthur et al, 2015; Perin et al., 2017), professional disciplinary identity (Mitchell et al., 2021), self-determination (Van Blankenstein et al., 2019), epistemological beliefs (Dowd et al., 2019), psychological well-being (Jonas & Hall, 2022), and the impact of online writing instruction (Miller et al., 2015; Miller et al., 2018; Mitchell et al., 2017a).

Next discussed in greater detail are the two most frequently measured associated variables—writing performance and writing apprehension or anxiety, as well as findings related to changes in writing self-efficacy over time.

Writing Performance

Writing performance was the most assessed associated variable in writing self-efficacy research and was evaluated in 70% of studies included in this review after quality appraisal (35 studies). This literature contains many criticisms of the measurement of writing performance pointing to issues with rater subjectivity as well as artificial attempts to objectify performance outcome assessments by exclusively assessing mechanical aspects of writing unrealistic to real world writing evaluation (Mitchell et al., 2017a; Mitchell & McMillan, 2018). Of the 35 studies that included writing performance as an outcome, two assessment strategies prevailed: (1) requiring students to write within a time limit or to complete the writing during class time (13 studies, 37.1%) and (2) including as data the naturalistic essays assigned in the course from where students were recruited as participants (14 studies, 40.0%). Some remaining studies used GPA as a proxy measure for academic performance. There is a temporal trend that timed essays are a feature of the first 20 years of all writing self-efficacy studies published 1984–2003 (75% timed essays versus 8% using holistic essays), and holistic essays are a feature of studies from 2004 to present (33% holistic essays versus 21% timed essays).

The most common method of scoring the quality of the writing was via the use of a holistic grading rubric, which we defined as a rubric that considered broad multidimensional features of writing such as content and ideas of the writing in addition to considering grammar and mechanics (60%, 21 studies). Use of holistic scoring strategies is more frequent in studies published from 2004 to present (45% of all studies compared to 23% of all studies published prior to 2004). The next most common scoring choice was to standardize the scoring via factors related to the study research question broadly (25%, 8 studies). In one case of standardized rubric creation, the performance of writing was not included as a study variable, but the writing samples were assessed for features of science reasoning (Dowd et al., 2019). In other studies, writing was assessed by matching the rubric to the items assessed on the writing self-efficacy measure (12.5%, 4 studies). One study used a broad ordinal rating of a set of naturalistic essays as poor, fair, or very good (Lavelle, 2006).

We also examined all findings that explored the relationship between writing self-efficacy and writing performance. These findings were widely variable and context specific with no detectable pattern of what contextual features might produce high or low correlations between performance and writing self-efficacy. In 13 of the 35 studies evaluating writing performance (37.1%), writing self-efficacy and performance were both assessed, but no calculations examining the relationship between the two variables were performed or reported. This occurred usually in studies where the research questions focused on group comparisons between conditions or pre and post an educational intervention. In a few of these studies, it was possible that negative findings resulted, and the calculation was not reported in the publication. Regression analysis to predict writing performance was reported in 9 of the 35 studies (25.7%) with β scores (when reported) for self-efficacy as the independent variable ranging from − 0.02 to 0.60 (mean β = 0.26). Only two studies reported a β > 0.40 (Meier et al., 1984; Prat Sala & Redford, 2012). These two studies were outliers as most β scores reported were under 0.15.

Most studies that reported a relationship between writing self-efficacy and performance used Pearson’s r correlations (16 studies, 45.7%). In studies that used student writing samples completed during class time or as take-home assignments, r values ranged from − 0.11 to 0.41 (mean r = 0.22) with the highest correlations appearing in Mitchell and McMillan (2018). The majority of the r values reported were less than 0.25. Three studies reported r values that related writing self-efficacy to student GPA ranging from r = 0.09 to 0.46 (mean r = .26) with the highest r values found in Mitchell and McMillan (2018). Two studies used a Spearman rank order technique dividing the sample into high, medium, and low self-efficacy levels and/or high- and low-grade categories with rs values reported at 0.42 (Prickel, 1994) and 0.40 (Lavelle, 2006).

Writing Apprehension or Writing Anxiety

Writing apprehension and anxiety were measured in 17 studies (34%). In 13 of these studies (76.5%), findings describing the relationship between writing self-efficacy and apprehension/anxiety were reported. The most common choice for measurement was either the full or a modified version of Daly and Miller’s Writing Apprehension Test (1975; e.g., Goodman & Cirka, 2009; Huerta et al., 2017; Mitchell et al., 2021; Pajares & Johnson, 1994; Prickel, 1994; Quible, 1999; Sanders-Reio et al., 2014; Wiltse, 2002). Writing apprehension or anxiety is decreasing as a standard associated variable in publications from 2004 onward (found in 28% of all studies published from 2004 onward and in 52% of all studies published prior to 2004).

Anxiety has been used an equivalent variable to apprehension including use of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (Meier et al., 1984; Mitchell et al., 2017a) or other method of measuring anxiety, such as two researcher-created items (Martinez et al., 2011) or a 0–100 visual analog scale (Mitchell et al., 2017a; Mitchell & McMillan, 2018). The most reported analysis exploring the relationship between apprehension/anxiety and writing self-efficacy was Pearson’s r correlation with scores ranging from − 0.17 to − 0.78 (mean r = − 0.49).

When apprehension or anxiety was used as a variable to predict writing self-efficacy in regression models or structural equation models, β ranged from − 0.43 to − 0.75 (mean β = − 0.63). Most reported correlation coefficients were in the high moderate range. High moderate statistical relationships are more likely to be reported when clearly validated tools are used for both writing self-efficacy and apprehension. Studies using Daly and Miller’s Writing Apprehension Test (1975) produced more consistent findings than the anxiety tools. The high moderate relationship between writing self-efficacy and writing anxiety/apprehension gives confidence that this is an effective research choice when study goals include writing self-efficacy instrument validation.

Changes in Writing Self-Efficacy Over Time

Twenty studies (40%) performed analyses that assessed the change in writing self-efficacy over time. Most studies found that writing self-efficacy demonstrated statistically significant improvement in a context where writing self-efficacy scores were assessed at the beginning and the end of a single term of study (Dowd et al., 2019; Goodman & Cirka, 2009; MacArthur et al., 2016; Miller et al., 2015, 2018; Mitchell et al., 2019; Quible, 1999; Woody et al., 2014). Three studies did not achieve statistical significance pre to post term (Martinez et al., 2011; Mitchell et al., 2017b; Penner, 2016), and two studies found a decrease in self-efficacy from pre to post term (Lackey, 1997; Zimmerman & Kitsantas, 2002). Study sample size and timing of when the pre and post-test questionnaires were given to samples would contribute to the variability in this finding as well as if study procedures trained students how to better self-evaluate their own writing abilities. Two studies (Jones, 2008; Pajares & Johnson, 1994) found mixed results when examining writing self-efficacy by subscales; some writing self-efficacy subscales showed improvement from pre to post test; others showed no improvement at all. It should be noted that studies reporting the individual subscale results for change over time were rare, even when multidimensional tools were used.

A different picture emerges when exploring the four studies that examined change in writing self-efficacy over a longer term using three or more data collection time points (Hood, 2018; Mitchell et al., 2017a; Mitchell & McMillan, 2018; Van Blankenstein et al., 2019). Hood (2018) and Van Blankenstein et al. (2019) found that writing self-efficacy improved in initial testing but remained the same or decreased by the third measurement. Mitchell et al., (2017a, 2017b, 2017c) included a time control period before the initiation of the writing course and found that writing self-efficacy did not change in the time period prior to the course starting but increased significantly from pre-course to post-course participation. In an extension of this same study, Mitchell and McMillan (2018) followed up on this same cohort and observed writing self-efficacy levels to fluctuate across a curriculum, having dropped significantly from the end of the writing course to the next data collection (2 years later) rising again by the final data collection which took place at the end of the same academic year. These authors concluded that writing self-efficacy changes were sensitive to contextual changes including instructor attitudes in the writing environment. Rather than continuing to increase over time once a course ends, writing self-efficacy seems to consistently drop when students move into a new course or new writing context.

Exploring Contexts of Writing Self-Efficacy Studies

Research question 2 asked: What is the nature of writing contexts in studies writing self-efficacy, including the environment for writing, pedagogical strategies, and interventions tested? Writing context categories are outlined via general categories in Table 1 including discipline, year of study, and type of writing course. Most writing self-efficacy studies were contained to a single academic term (33 papers—66%) with writing environments that were either specific to teaching writing skills (19 papers—38%) or a writing intensive disciplinary course (14 papers—28%). Other studies assessed writing self-efficacy related to writing center use, effectiveness of writing workshops, or asked students enrolled in an institution about their global postsecondary writing experiences.

Descriptions of Writing Instruction Experienced by the Participants

A detailed examination of the nature of the writing instruction experienced by study participants was conducted. In the case of 25 (50%) papers, there was no specific description of the nature of writing guidance given to the students in the sample. For at least 9 of these studies, lack of discussion of writing pedagogies is possibly because the sample population was global to an institution (e.g., multiple program years, multiple disciplines, and/or multiple courses within a single study). Three studies (6%) were conducted in a writing center environment and provided a basic description of writing center services and qualifications of the tutors employed (Aunkst, 2019; Schmidt & Alexander, 2012; Williams & Takaku, 2011).

Interventional Studies

Nine studies (18%) identified their methods as interventional involving one or more comparison conditions and employing either random or non-random methods of study group assignment. Table 4 outlines the different interventional choices and results. All the studies identifying their methods as interventional assessed writing performance and most studies assessing writing performance (7/9) used timed in-class writing performance assessments with one of the seven studies examining both a naturalistic and a timed writing task. The interventions focused on sentence combining (Gay, 2019; Zimmerman & Kitsantas, 2002), effects of mood primers (Vanhille et al., 2017), risk taking in writing (Taniguchi et al., 2017), a writing self-efficacy intervention (Hood, 2018), modeling or observational learning about writing tasks (Zimmerman & Kitsantas, 2002), training faculty to teach specific writing tasks (MacArthur et al., 2015), demonstration of assignment specific writing tasks (Nicholas et al., 2005), and scaffolding of assignments across the term (Miller et al., 2015, 2018). Findings across the studies showed that interventions had variable effects on both writing performance and writing self-efficacy, sometimes showing improvement and sometimes showing no change based on condition. As Table 4 shows, many of these studies had small sample sizes with under 20 participants in each condition.

Descriptions of Course Content Described in Cross-Sectional or One-Group Pre-test Post-test Research

In 11 cross-sectional or pre-test/post-test studies (22%), descriptions of course content with varying levels of detail were included. In these studies, pedagogical choices included focuses on mechanics, style guide, or other surface characteristics of writing (Penner, 2016; Rankin et al., 1993); mastery of specific writing tasks (Pajares & Johnson, 1994); self-regulation strategies including goal setting, planning, and revising (Johnson, 2020; MacArthur et al., 2016); training of tutors or teaching assistants (Goodman & Cirka, 2009; Stewart et al., 2015); scaffolding course content to assist students with assignment preparation (Huerta et al., 2017; MacArthur et al., 2016; Mitchell et al., 2017b; Mitchell et al., 2017a; Penner, 2016; Perin et al, 2017); iterative feedback pedagogies in individual or small groups settings (Pajares & Johnson, 1994); and peer review (Pajares & Johnson, 1994; Penner, 2016; Van Blankenstein et al., 2019).

Exploring Trends in Writing Self-Efficacy Measurement

Research question 3 asked: What trends emerge about writing self-efficacy measurement within this body of research? This analysis of measurement of writing self-efficacy was structured to build upon the analysis reported in Mitchell et al. (2017c), who analyzed writing self-efficacy measures developed for postsecondary contexts and identified 11 tools that were considered relevant representations of writing self-efficacy. Of the papers describing those 11 tools, 9 met the inclusion criteria for this study (Jones, 2008; MacArthur et al., 2016; Meier et al, 1984; Mitchell et al., 2017b; Prat-Sala & Redford, 2010; Prickel, 1994; Schmidt & Alexander, 2012; Shell et al., 1989; Zimmerman & Bandura, 1994). The two not included were studies eliminated due to second-language or non-English writing contexts. Although we did not limit inclusion criteria to studies that used those nine tools, we did track the use of these nine tools to draw comparisons.

History of Use of the Nine Questionnaires Identified in Mitchell et al. (2017c)

All nine tools had published some evidence of their reliability and validity as reported in Mitchell et al., (2017c). Of the papers describing these nine tools, four were publications describing the initial psychometric testing of the instrument (MacArthur et al., 2016; Prickel, 1994; Schmidt & Alexander, 2012; Zimmerman & Bandura, 1994). For the Mitchell et al. (2017b) tool, authors confirmed tool validation which is reported in Mitchell et al. (2021) and Mitchell and McMillan (2018). One of the nine tools identified in this review has never been used in published research beyond its initial testing in the doctoral dissertation of its author (Prickel, 1994). Two of the nine tools have not been used outside of subsequent studies conducted by the same author teams (Meier et al, 1984; Mitchell et al., 2017b). Other tools have had limited use. Prat-Sala and Redford (2010) was used once outside of its initial development and the Jones (2008) tool was used twice.

Five of the nine tools analyzed in Mitchell et al. (2017c) were the most frequently used tools in the studies examined for this review (see Table 1). Shell et al. (1989) and Zimmerman and Bandura (1994) (used in 18% and 16% of studies, respectively) were the two most frequently used tools either with or without modification from subsequent authors. The most common modification of the Shell et al. (1989) tool was to not use the tasks subscale from the tool’s initial reporting as it was simply a listing of common writing genres, many of which may not have been relevant for most academic writing contexts (e.g., instructions for a card game).

Additional Measurement Strategies Observed

The nine tools analyzed in Mitchell et al. (2017c) account for the measurement of writing self-efficacy in 37 studies included in this analysis (74%). The remaining 13 studies (26%) used tools with various developmental origins. None of these 13 tools were used more than once, and adequate validation evidence was not presented across publications. Some of these tools had developmental origins that would be considered what Flake et al. (2017) referred to as “on-the-fly” instrument development (3 studies—6%). On-the-fly tool development was a common feature of five out of the six studies that were eliminated from this review due to failing to reach a 50% threshold in our quality appraisal. On-the-fly tools contained items that were developed specific to the study aims or with intention to be a close match to the objectives of the writing assignment but were not based on an existing validated tool or presented with validation information following their use. Other tools identified their origins as modifications of existing tools that were not initially developed for assessing writing (4 studies) or existing tools that were developed to assess writing self-efficacy in populations of elementary or secondary students (4 studies). These 13 studies represent 13 unique uses of the tools they describe. That is, within a body of literature exploring postsecondary writing-self efficacy in English writing contexts, 22 unique measurement approaches were identified. With the six studies eliminated by quality appraisal, five had unique measurement approaches, meaning in the entire body of work, there were 27 unique measurement approaches total. This count does not include considerations of the many modifications reported in manuscripts to the 9 tools analyzed in Mitchell et al. (2017c). Additionally, we also wish to highlight two promising tools of recent introduction into the literature that represent rigorous tool developments (Golombek et al., 2018; Mitchell et al., 2021) both being the only two tools presently in publication which have used modern psychometric approaches.

Multidimensionality of Writing Self-Efficacy Measurement

Multidimensionality of tools was also considered. The multidimensionality criteria were considered met if the tool or measurement approach involved a tool with multiple subscales or the triangulated use of more than one writing self-efficacy instrument. Tools identified as having on-the-fly development were considered unidimensional. Five studies included two or more writing self-efficacy instruments as part of their data collection. Williams and Takaku (2011) used Shell et al. (1989) and Zimmerman and Bandura (1994). Lambert (2015) used Jones (2008) and Zimmerman and Bandura (1994). Mitchell and McMillan (2018) and Mitchell et al. (2019) used Mitchell et al. (2017b) and Schmidt and Alexander (2012). Finally, Mitchell et al. (2021), as part of their concurrent validity assessments of their new instrument (Situated Academic Writing Self-Efficacy Scale), included Mitchell et al. (2017b) and Shell et al. (1989).

Multidimensionality was achieved in 30 studies (60%). Of the nine tools examined in Mitchell et al. (2017c), six were multidimensional tools including Shell et al. (1989) (only if both the skills and tasks scale was used and many studies dropped the tasks scale); Prickel (1994) had four subscales they labeled general writing, idea and sentence generation, paragraph and story generation, and editing/revising; Zimmerman and Bandura (1994) identified 7 subscales (four were labeled: self-regulation for writing, verbal aptitude, writing skills, and concentration and self-evaluation), but, as reported by the authors, the scale can be mathematically forced to single factor when items 9 and 20 are removed; Jones (2008) labeled three factors tasks, skills, and approach; Schmidt and Alexander (2012) identified three factors labeled local and global writing processes, physical reaction, and time/effort; and McArthur et al. (2016) labeled three factors exploring tasks, strategies, and self-regulation but also in their analysis forced the scale to mathematically fit a single factor. One other study used a multidimensional tool. Johnson (2020) modified an existing multidimensional tool designed for assessing writing self-efficacy in children. The collective names of the subscales in these five multidimensional tools betray the writing as a product perspective (emphasising textual features at the sentence level) and the cognitive process perspective (e.g. self-regulation) emphasis within this body of literature.

Newer multidimensional tools appearing in the literature have undergone rigorous psychometric testing, including Golombeck et al. (Self-Efficacy for Self-Regulation of Academic Writing (SSAW); 2020) and Mitchell et al. (Situated Academic Writing Self-Efficacy Scale (SAWSES); 2021). Both instrument validations used multistudy processes for scale development and conducted confirmatory factor analyses using a different sample from their preceding exploratory factor analysis studies. Of the studies included in this review, these were the only two that reported these more modern methods of psychometric testing. Golombeck et al. (2018) developed their scale from cognitive process theories in self-efficacy and self-regulation with a focus on the self-monitoring tasks of cognitive process. Their scale identified three subscales labeled forethought, performance, and self-regulation. Mitchell et al. (2021) used a combined theoretical approach drawing from a model of socially constructed writing as well as self-efficacy theory. They achieved three subscales labeled writing essentials, relational-reflective writing, and creative identity. The authors identify the tool as capable of assessing developmental facets of writing because the subscales had reported ranked difficulty and discrimination properties. The writing essentials subscale had the lowest reported item difficulty; creative identity had the highest reported item difficulty with relational-reflective falling between.

Unidimensional tools often used limiting approaches to operationalizing the concept such as focusing on surface textual features of writing (grammar, sentence formation, vocabulary, and mechanics) or observable writing tasks. That writing self-efficacy measurement has prioritized the assessment of cognitive features of writing aligns with Bandura’s perspective on the concept as well as the cognitive process models of writing (Mitchell et al., 2017c). These theoretical perspectives neglect the contextual and social influences on writing self-efficacy which has only recently started to become visible in this body of work and was most overtly acknowledged in the new development of a situated writing self-efficacy tool presented in Mitchell et al. (2021).

Exploring Practical Implications Noted Across Writing Self-Efficacy Studies

Research question 4 asked: What have writing self-efficacy researchers identified as their implications for writing pedagogy based on their research findings? While findings, research approaches, and measurement in writing-self efficacy research are highly variable and context-specific across this literature, researchers who have used writing self-efficacy as a construct in their research have identified several implications for teaching and learning based on their findings. The following thematic categories were identified by examining the results and discussion sections of all the papers included in this review to narratively synthesize researchers’ conclusions about the impact of their findings on writing self-efficacy and how their findings can be translated into in-class teaching strategies.

A Tendency to Overestimate Writing Self-Efficacy in Self-Report

A common conclusion among the included studies is that writing self-efficacy self-report assessments are prone to student overestimation (Jones, 2008; McCarthy et al., 1985; Meier et al., 1984; Mitchell et al., 2017a; Quible, 1999; Stewart et al., 2015; Zimmerman & Kitsantas, 2002). This tendency to embellish writing self-efficacy scores was often attributed to a student’s novice status. For example, in one study, novice students had previous writing success often in lower-level academic contexts (e.g., high school) and believed their writing abilities would be perceived as equally effective at a higher level of writing such as a university level class (Mitchell et al., 2017a). Similarly, Zimmerman and Kitsantas, (2002) reported lower writing self-efficacy from pre- to post-course for reasons they attributed to student failure to understand their own abilities in a context where the writing demands had increased dramatically from their previous writing experiences. Students may believe they have a set of skills from one environment and then discover they have difficulty transferring those skills to their new environment. Mitchell and McMillan (2018), in an across the curriculum exploration of writing, observed a continuous fluctuation of writing self-efficacy levels across a curriculum, which they attributed to increasing complexity of assignments from year to year and changes in teacher approach to guiding writing.

Some intervention studies cited calibration effects for non-significant findings, noting that self-efficacy lowered because the students through the intervention offered in the study were able to learn to better self-assess their own writing abilities. Jones (2008) observed that the students most prone to overinflating their sense of writing ability at the start of a course of study presented initially as weaker writers.

Recognition of the Developmental Nature of Writing Ability

Writing self-efficacy researchers in their conclusions have noted how their research appears to be making a contribution to the understanding of the developmental nature of writing ability. This observation is derived through researcher observations about how the relationship between writing performance and writing self-efficacy becomes stronger as proficiency develops (Prickel, 1994; Shell et al., 1989). Although studies included in this review noted that a single classroom represents a short period of time for such developments to be detected (Mitchell et al., 2017a; Penner, 2016), faculty can begin to demonstrate their commitment to writing self-efficacy improvement by spending time assessing these beliefs at the start of a course (Zimmerman & Bandura, 1994). New scale developments that consider the developmental nature of writing in their construction may be able to assess writers’ developmental stage at the start of a given course and allow for the development of teaching approaches that target student self-identified areas where they lack self-efficacy (Golombek et al., 2018; Mitchell et al., 2021).

The Importance of Teacher Attitudes and Instructional Climate

Several researchers observed in their conclusions the important role of the instructor in front of a writing classroom in influencing student writing self-efficacy beliefs. Instructor attitudes toward student capabilities and presentation of a classroom atmosphere that sets a positive tone is critical to self-efficacy development (Ekholm et al., 2015; Goodman & Cirka, 2009; Mitchell et al., 2017a). For example, findings show positive effects related to adaptive instructor beliefs such as growth mindset (i.e., the belief that writing can be taught; Sanders-Reio et al., 2014), and adaptive instructional practices such as persuading students that they have the skills and abilities to succeed (Quible, 1999). This support may be what is needed to also enhance psychological well-being among students, especially at the graduate level where writing self-efficacy has been identified as a predictor of feelings of emotional exhaustion and imposter syndrome (Jonas & Hall, 2022). Instructor affect and willingness to talk about their own beliefs about writing may be the keys to writing self-efficacy development. As more current research demonstrates that writing context can play a critical role in writing self-efficacy levels (Mitchell et al., 2021), instructional practices can be used to change writing self-efficacy (Sanders-Reio et al., 2014).

For faculty to be able to nurture this positive environment, their own self-efficacy in their abilities to teach writing needs to be nurtured (Woody et al., 2014). Lack of capacity to teach writing in faculty who are experts in their content area but not necessarily in the instruction of writing was as identified as a contributing contextual confounder to the development of writing self-efficacy in students (Miller et al., 2015; Mitchell et al., 2017a; Woody et al., 2014).

The Influence of Feedback on Writing Self-Efficacy

Many study authors described implications related to the giving and receiving of feedback that may impact writing self-efficacy. The relationship between feedback and writing self-efficacy may be reciprocal in that feedback will affect writing self-efficacy (Jones, 2008), but writing self-efficacy levels at the time of receiving the feedback may affect how students use that feedback (Wiltse, 2002). Feedback-giving strategies can also be demoralizing (Goodman & Cirka, 2009). Faculty are ultimately responsible for ensuring that students understand the feedback they received (Mitchell et al., 2019). The strongest feedback approaches are iterative (Mitchell et al., 2019) and task specific (Lackey, 1997). As with writing demands, feedback is also context dependent. For this reason, Mitchell et al. (2019) warn that feedback may not be transferable from context to context or genre to genre because instructions given in one context may be not best practice in the next context or genre of writing.

Approaches to Teaching and Guiding Writing

The authors of the research studies also made statements in their conclusions about the nature of how writing self-efficacy studies can improve approaches to teaching and guiding writing. Because writing is contextual, specific writing tasks and genres assigned may require a different approach to writing. Students with low writing self-efficacy especially need specific guidance (Prat-Sala & Redford, 2010; Schmidt & Alexander, 2012). Scaffolding of tailored processes was a common suggested support (Miller et al., 2018; Mitchell et al., 2017b; Rayner et al., 2016), as was discipline-specific writing workshops offered at the graduate level (Jonas & Hall, 2022). Approaches such as using fewer assignments with more opportunities for drafts and revision or assignments broken down into pieces are also considered self-efficacy building approaches (Sanders-Reio et al., 2014). Hood (2018), for example, suggests that these scaffolded assignments should be designed to de-emphasize writing outcomes and grammar and mechanics and increase focus on iteration and dialogue between reader and writer. Authors of several studies suggest that the writing requested from students must be closely linked to course content, the students’ discipline, or involve choice of topic to increase student engagement with the writing process (Jonas & Hall, 2022; Mitchell et al., 2017b; Van Blankenstein et al., 2019). In disciplinary programs, it may be possible to consciously thread and monitor the writing activities of students across their academic programs (Mitchell & McMillan, 2018).

Due to the potential positive effects of modeling, involvement of peers was also considered an effective teaching strategy, as noted by several authors in their conclusions (MacArthur et al., 2015; Miller et al., 2015, 2018). Mitchell et al. (2017a, b) observed that students instituted their own peer modeling practices to obtain feedback and suggested that instructors’ involvement in facilitating that process would be more effective. MacArthur et al. (2015) expand on this idea by noting that students need to be trained in the peer review process, use of rubrics, and self-assessment. Training students in these evaluation practices may be reciprocal—with potential positive and simultaneous effects on students’ self-efficacy beliefs and self-evaluative metacognitive abilities (Lavelle, 2006).

Discussion

The purpose of this scoping review was to describe the associated variables appearing alongside writing self-efficacy, changes of writing self-efficacy over time, the types of writing strategies and interventions acting as the contextual backdrop to this area of research, trends in measurement choices through the history of this research, and the implications for pedagogy reported by authors of these studies based on their findings. In total, 50 unique studies were included. The large number of papers included in this review, in particular those published in the last seven years, is an indication of the expanding interest in writing self-efficacy as a critical concept impacting writing development at the postsecondary level. Although this body of literature is diverse in method, objectives, and reported outcomes, we believe this review will be useful to researchers in future empirical examinations of writing self-efficacy.

Comparing the Findings of Postsecondary Writing Self-Efficacy to K-12 Writing Self-Efficacy

This review is the first to examine writing self-efficacy trends as they specifically apply to postsecondary populations. The urgency of finding a method of researching writing to impact classroom practices and improve the writing of adult learners is evident in the explosion of research conducted to explore writing self-efficacy from 2014 to 2021—the era from which more than half papers in this review, spanning 1984–2021, were published. Authors examining postsecondary and graduate students often employ different research strategies than those used in K-12 research. Most notably, they use different measurement tools to assess writing self-efficacy. While there is some crossover use of tools from K-12 research in the postsecondary research, most tools have been developed specifically for the postsecondary population. K-12 tools adopted for use in postsecondary populations have required modification to accurately reflect context and language used in postsecondary writing activities. Postsecondary and graduate student populations face high stakes through grading that impacts their future career paths, publication expectations, increased research and literature search requirements, and expected use of academic and disciplinary registers in word choice and sentence structure. These are only a few of the many significant contextual differences between researching K-12 writing self-efficacy and postsecondary writing self-efficacy.

Despite contextual differences, K-12 and postsecondary research share some similar findings. Contrary to theory (Bandura, 1986), neither area has been able to produce convincing evidence that writing self-efficacy can consistently and strongly predict writing performance with both bodies of work reporting correlations of about 0.20 on average between the two variables. Not surprisingly, the relationship is hypothesized as more likely to be detected when the measurement of self-efficacy and the writing performance assessment match in their criteria (Pajares & Valiante, 2006); however, obtaining this match requires stripping the measurement of writing self-efficacy and the measurement of writing performance to an oversimplification which begs the question if finding that relationship under those conditions holds any real-world meaning. In the postsecondary studies we reviewed, some of the methodological shortcomings of the body of work—especially a shortage of interventional and longitudinal research—may be holding back advancement of knowledge in this area. Additionally, the postsecondary literature suggests that some of the relationship between writing performance and writing self-efficacy is likely mediated via various factors such as self-efficacy for academic achievement (Zimmerman & Bandura, 1994); however, the statistical model building needed to test hypotheses of mediation and predication is seemingly rare across this research (7 studies, 14%).

Other variables that have appeared in both K-12 and postsecondary research include writing apprehension, which has a consistent moderate to strong negative relationship with writing self-efficacy (Goodman & Cirka, 2009; Mitchell et al., 2021; Pajares & Johnson, 1994; Sanders-Reio et al., 2014; Vanhille et al., 2017). Studies exploring reading self-efficacy have also demonstrated promising links to writing self-efficacy and performance (Jonas & Hall, 2022; Prat-Sala & Redford, 2012). Assessing whether students like or dislike writing appears a successful marker of whether a student will have high or low self-efficacy (Mitchell et al., 2021; Zumbrunn & Bruning, in press).

It is reasonable to assume that the writing beliefs students bring with them to postsecondary settings begin to form during their K-12 experiences. Though beyond the scope of our review, authors of K-12 writing self-efficacy reviews (Klassen, 2002; Pajares, 2003; Zumbrunn & Bruning, in press) and others (Ekholm et al., 2018) call attention to the important role teacher beliefs and instruction may play in predicting student writing beliefs and performance.

The Impact of Study Variability on the Review Findings: the Variables Chosen, Contextual Differences, and Measurement Choices

The two variables most commonly appearing alongside writing self-efficacy in the studies reviewed were writing performance and writing apprehension or writing anxiety. Many studies also examined change in writing self-efficacy over time. Studying local context in a specific course or program meant that writing context, instructional practices, and choices in measurement of writing self-efficacy were influential in study outcomes. The results reported in studies exploring writing performance were mixed due to the variability in how writing performance was assessed across studies. In the same studies, there was variability in the questionnaire used to measure writing self-efficacy, ranging from multidimensional to unidimensional. Some measures were developed without formal validation, and other tools measured limited aspects of writing, such as grammatical competence or cognitive tasks.

Variability in context and measures across the studies makes it difficult to comment on the overall quality of the body of this work or the statistical effectiveness of any given writing pedagogy. A normative methodological choice in this research was to conduct the studies over a single term. Given writing performance is likely developmental, it would be unrealistic to expect writing ability to change in meaningful ways in such a short time period (Mitchell et al., 2017a; Penner, 2016). In examining studies that assessed change in writing self-efficacy over time, findings suggest that students need attention from faculty, clear feedback, and practice with writing to improve their writing self-efficacy beliefs, as these were features common in the pre-test post-test studies where a statistically significant change in writing self-efficacy was reported. Similar to K-12 reviews of self-efficacy (Camacho et al., 2021; Zumbrunn & Bruning, in press), the presence of the instructor was noted in several studies to be a key ingredient in this improvement over time, adding to the evidence of the contextual nature of writing self-efficacy development (Ekholm et al., 2015; Goodman & Cirka, 2009; Mitchell et al., 2017a).

The Conclusions Authors Have Drawn About Writing-Self Efficacy Should Impact Future Research Choices and Pedagogical Interventions

The narrative analysis of how authors described the implications of their work for writing pedagogy provides valuable insights into the potential of writing self-efficacy as a variable for research. The first common conclusion noted across included studies related to novice students’ tendency to overestimate their level of writing self-efficacy. Such miscalculations of writing self-efficacy scores highlight the need to include pedagogies to guide students to understand how to calibrate their perceptions of their abilities with writing (Zumbrunn & Bruning, in press). Likely students’ self-perceptions of writing self-efficacy are contextual. They may also be impacted by students attending more to what they can do to meet teacher expectations and maximize their grades, than to their actual abilities (Mitchell et al., 2021). Common conclusions drawn by authors of included studies suggest that peer involvement may also play a role in self-evaluation when students have the opportunity to observe models of writing from other students aiming to meet the same writing objectives. Some research has shown that postsecondary students may create their own peer feedback networks to help self-evaluate how their own writing is meeting teacher objectives, if such peer groups are not organized by the instructor (Mitchell et al., 2017a). We see potential for these conclusions to inspire interventional and pedagogical research on how to help students calibrate their ability to judge their own writing abilities, as well as the influence of peer and writing community classroom activities.

Other common conclusions noted across the reviewed studies expand our understanding of the influence of writing context and instructor direct involvement on student writing development. Specifically, findings suggest that teacher attitudes and intentional instructional choices, such as scaffolding and intentional feedback, can meaningfully influence student writing self-efficacy. We also see these as potential areas for intervention and pedagogical research. For example, future research might investigate the impact of iterative feedback strategies and their respective influence on writing self-efficacy. A tool assessing self-efficacy for self-assessment may be useful as a route to gathering information about these abilities (Varier et al., 2021).

Additional intervention studies exploring teacher self-efficacy for teaching writing would also be relevant. Given that faculty are rarely educated in their graduate programs as to how to teach writing and consider themselves content experts first and foremost (Miller et al., 2015; Mitchell et al., 2017a; Woody et al., 2014), understanding the needs of faculty for supporting students is critical to enhancing student self-efficacy for writing. Existing validated questionnaires are available for such investigations such as the Individual and Collective Self-Efficacy for Teaching Writing Scale developed for high school teachers but easily modifiable to fit postsecondary teaching contexts (Locke & Johnston, 2016).

Limitations

No review is without limitations. Our review of writing self-efficacy focused solely on quantitative research. The exclusion of several qualitative studies may have contributed insights to this body of work. Removal of the six papers from the review due to low-quality appraisal may have changed some findings in this descriptive review—in particular, making the methodological choices of researchers seem more robust as a whole—however, where glaring differences occurred, we indicated how results differed prior to removal of the six papers. Additionally, one interventional paper (van der Loo et al., 2016) was removed due to low quality but was published as conference proceedings that highly restricted article length which might have limited their ability to report on methodological factors screened in the quality appraisal. A second limitation is that we opted to only include English-written papers, potentially missing important work written in other languages. These limitations can be overcome in future reviews.

Future Directions

Our findings point to several areas for future theoretical and methodological directions in research on the writing self-efficacy beliefs of postsecondary students.

A Need for Longitudinal Studies of Writing Self-efficacy to Capture the Development of Writing

First, there is a need for longitudinal studies of writing self-efficacy. The majority of the studies included in this review were conducted using cross-sectional or pre-test post-test methods on small groups of students in a single-classroom environment. The nature of postsecondary educational research often provides for easily accessible samples, captive classroom audiences, and allows for research that can be conducted on limited funding. However, to make a true contribution to the science of writing self-efficacy, we agree with observations made by Camacho et al. (2021) and Zumbrunn and Bruning (in press) that there is a need for more longitudinal approaches that can contribute to understanding the developmental nature of writing. Contextual changes such as differing instructional strategies and teacher beliefs and attitudes about their role in writing instruction will be critical to understanding the impacts on that development. We also need longitudinal research that will help to understand the relationship between writing self-efficacy and the increasing complexity of writing demands as students reach higher levels of their postsecondary programs (Mitchell & McMillan, 2018).

The K-12 and postsecondary writing self-efficacy research bodies of literature have operated in silos. Some of the increased interest in writing self-efficacy in postsecondary populations has emerged due to faculty frustration with what they perceive to be a palpable diminishing of writing skills of students entering postsecondary education. Writing is developmental, and the vast majority of a student’s writing development occurs before they enter university. For faculty, this makes the K-12 teachers an easy scapegoat for the poor writing they observe in their classes; however, very little is known about this bridge between K-12 writing and university writing. Many university faculty have a knowledge deficit with respect to how writing is taught in high schools and do not recognize the tacit writing expectations they hold that are disciplinary and socially constructed (Mitchell et al., 2019). The postsecondary literature has observed a tendency for students to overestimate their self-efficacy at points of transition (high school to university, postsecondary to graduate school). These transitions, their role in writing development, and interventions to promote ease of transition all need further research attention.

Additional Research from a Situated Perspective in Combination with Current Cognitive Approaches

We also see a need for research to be situated. Bandura’s (1997) foundational work on social cognitive theory was present throughout as the theoretical approach in this body of research; exploration of theories outside of the cognitive domain such as socially constructed theories was rare. Cognitive approaches are effective pragmatically to provide concrete tasks to guide the act of writing, but social approaches to writing may be more effective for exploring community and disciplinary factors affecting writing performance beyond individual factors (Mitchell et al., 2021). Better integration of social theories and cognitive theories may be useful to understanding the many systemic and contextual factors that impact writing performance (Camacho et al., 2021; Zumbrunn & Bruning, in press).

Advancing Understanding of Diversity in Writing Self-efficacy Assessment

Related, our review points to the importance of advancing diversity in writing self-efficacy research. Our review found no evidence of gender differences in writing self-efficacy beliefs, and inconsistent results were present with respect to race and English as a second language, but very few studies examined these characteristics in their populations beyond reporting descriptive differences between the groups, which could not conclusively detect anything meaningful to help guide writing instruction. Gender and race experts note that comparing genders examines influences of sexism on the outcome and comparing races examines the influence of racism, though neither race or gender produce meaningful results when oversimplified to a dichotomy (Inoue, 2015). Pajares (2003) acknowledged nearly 20 years ago that racial differences were present and since that time no researchers have linked these racial differences to racial discrimination and systemic inequities. Writing can be studied to understand how pedagogy can discriminate and how antiracist writing pedagogies can improve self-efficacy in all students (Inoue, 2015). Inequities exist in writing instruction and evaluation that likely impact student motivation to write and their ultimate sense of identity in their chosen professions. One of the largest inequities is the stronghold of beliefs in one standard English vernacular which serves to other students of colour and multilingual students whose writing and speech strays from that standard with consequences to their self-perceptions as writers and their identities as postsecondary scholars (Inoue, 2017; Poe, 2017; Sterzuk, 2015; Young, 2009).

Attention to Multidimensionality of Writing Self-efficacy and Its Impact on Affective Learning

Finally, we see the need for the consistent use of strong multidimensional measures of writing self-efficacy. Despite a large number of measurement options in the writing self-efficacy literature, researchers continue to develop unique tools for their own studies. We identified 22 unique measures of writing self-efficacy within these 50 studies, plus five additional on-the-fly tool developments that were eliminated after quality appraisal. Many of the existing tools are being used with their ongoing validity assumed even though they may have been initially validated with statistical methods that predated advanced computer coding and programming. Most of these measures were modified for use in some fashion and may include items that do not fully capture modern postsecondary writing contexts. Some of this history may in part explain the repeated on-the-fly development of writing self-efficacy tools, which is researcher behavior indicative of either a lack of engagement of the literature to locate validated tools or dissatisfaction with existing tools because they do not reflect the context of the research project (Mitchell et al., 2021). The approaches of on-the-fly tool development, constant modification of existing tools, and use of unidimensional tools that limit the definition of writing self-efficacy to surface mechanical or observable writing tasks are no longer useful for advancing understanding of this multidimensional construct. This observation is similar to what was observed in studies conducted in K-12 populations (Camacho et al., 2021; Zumbrunn & Bruning, in press). Future studies using multidimensional writing self-efficacy tools should report findings with each dimension of the scale used to understand the independent contribution of the dimensions of writing self-efficacy within their findings.

Conclusion