Abstract

School victimization issues remain largely unresolved due to over-reliance on unidimensional conceptions of victimization and data from a few developed OECD countries. Thus, support for cross-national generalizability over multiple victimization components (relational, verbal, and physical) is weak. Our substantive–methodological synergy tests the cross-national generalizability of a three-component model (594,196 fifteen-year-olds; nationally -representative samples from 77 countries) compared to competing (unidimensional and two-component) victimization models. We demonstrate the superior explanatory power of the three-component model—goodness-of-fit, component differentiation, and discriminant validity of the three components concerning gender differences, paradoxical anti-bullying attitudes (the Pro-Bully Paradox) whereby victims are more supportive of bullies than of other victims, and multiple indicators of well-being. For example, gender differences varied significantly across the three components, and all 13 well-being indicators were more strongly related to verbal and particularly relational victimization than physical victimization. Collapsing the three components into one or two components undermined discriminant validity. Cross-nationally, systematic differences emerged across the three victimization components regarding country-level means, gender differences, national development, and cultural values. These findings across countries support a tripartite model in which the three components of victimization—relational, verbal, and physical—relate differently to key outcomes. Thus, these findings advance victimization theory and have implications for policy, practice, and intervention. We also discuss directions for further research: the need for simultaneous evaluation of multiple, parallel components of victimization and bullying, theoretical definitions of bullying and victimization and their implications for measurement, conceptual bases of global victimization indices, cyberbullying, anti-bullying policies, and capitalizing on anti-bullying attitudes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Peer victimization is an increasing, worldwide problem with profound adverse implications for the well-being and mental health of victims (recipients of bullying), bullies (perpetrators of bullying), bystanders, and whole school communities (Due et al., 2005; Hemphill, 2011; Juvonen & Graham, 2014; Marsh et al., 2001, 2011, 2022; Mayer & Cornell, 2010; Olweus, 1991, 1993; Swearer et al., 2010). Peer victimization comprises intentional acts of aggression that victims perceive as harmful (Card & Hodges, 2008; Smith et al., 2019). Aggression may involve a ‘one-off’ or single-event set of actions. However, victimization in relation to bullying reflects sustained and repeated acts of aggression or intimidation, such as name-calling, physical threats, social exclusion, and verbal/physical assault. These acts can occur between individuals or groups. These repeated acts of aggression and intimidation happen in the context of an imbalance of power between the bully and the victim (Casper & Card, 2020; Marsh et al., 2011; Perry et al., 1988; Olweus, 1991, Rigby, 2007).

Repeated victimization is a serious risk factor for depression, psychopathology, physical ill health, and psychological distress (e.g., Kaltiala-Heino et al., 1999; Marsh et al., 2004a; Rigby, 2007). Adults victimized as children are more likely to have poorer mental and physical health, be less financially well-off, and have poorer social relationships (Wolke et al., 2013). Victimization during adolescence is associated with adverse outcomes in adulthood (e.g., criminal offending, alcohol abuse, drug use, risky sexual behavior, violence, depression, low self-esteem, suicidality, hospitalizations, sexually transmitted infections, and eating disorders; Turanovic & Pratt, 2019). In addition, students who witness verbal and physical violence at school are more likely to be aggressive, truant, and less engaged with school (Janosz et al., 2008). Thus, the impact of school victimization is pervasive and enduring, extending beyond bullies and their victims to the peer group, school, community, and even country (OECD, 2019a). Because victimization is the most frequent form of violence for school students (Menesini & Salmivalli, 2017), its adverse effects are of worldwide concern.

Based on social–ecological theory (Hong & Espelage, 2012), Bronfenbrenner’s ecological framework (Bronfenner & Morris, 2007), and early research conducted by Olweus (1978), the most widely recommended anti-bullying interventions are whole-school-based. These interventions emphasize whole-of-school awareness and monitoring, consistent responses, and strong anti-bullying policies (Juvonen & Graham, 2014). This includes interventions at the level of the school climate. They also focus on the children not directly involved as bullies or victims but as bystanders, defenders, or those who offer varying degrees of support to bullies or victims (Hong & Espelage, 2012; Salmivalli, 2010; Yoon & Bauman, 2014). Consistent with this, the whole-school approach also emphasizes changing attitudes that support bullying.

However, despite the huge costs of victimization, based on systematic reviews and meta-analyses of victimization research, Juvonen and Graham (2014) concluded that the results from victimization interventions were “disappointing” (also see Ng et al., 2022; Li et al. 2020). Juvonen and Graham based their conclusion on pre-2014 studies, particularly those included in the classic Farrington and Ttofi (2010) meta-analysis. However, in updating their classic meta-analysis, Farrington and colleagues (Gaffney, Ttofi, & Farrington, 2019) found weak effects (mean odds ratio = 1.22, CI = 1.09–1.38) marginally worse in 2019 than in 2009. Thus, post-2009 studies were even weaker—certainly not stronger—effects than earlier ones.

Even more worrisome, only a minority of the intervention studies used appropriately randomized control–trial (RCT) designs, and these RCTs had even smaller effects (also see Jiménez-Barbero et al., 2016). Furthermore, although most RCT studies used randomization at the school or class levels, few fully controlled for clustering effects with appropriate multilevel models. Ng et al.’s (2022) meta-analysis similarly concluded that intervention effects were “very small to small” and that these “marginally effective” results were generally consistent with previous meta-analyses. Ng et al. also reported that intervention effects to reduce victimization were even weaker than those targeting bullying.

Ttofi et al. (2011) reported that interventions for bullies were more effective for older students. However, age did not significantly moderate the intervention effects for victims in their meta-analysis. Furthermore, the Jiménez-Barbero et al. (2016) meta-analysis reported that interventions targeting younger children aged 10 or less were more effective than those targeting older children. On this basis, we conclude that there is no clear evidence that the disappointing effects vary as a function of age, but we note that more research is needed to clarify this issue.

Additionally, despite widespread efforts to reduce victimization, worldwide prevalence of victimization has remained steady or even increased (Harbin et al., 2019; OECD, 2019a). For example, OECD, (2019a,b) reports that in OECD countries, 23% of students reported being bullied at least a few times a month, and the incidence rate increased from 2015 to 2018. Prevalence rates are even higher in developing, non-industrialized countries (e.g., Craig et al., 2009; OECD, 2019a).

In our study, we address two major limitations in current victimization research: dimensionality (i.e., good measurement, number of components needed, and discriminant validity in relation to antecedents and consequences) and failure to test cross-national generalizability. These limitations limit understanding of victimization, so overcoming these limitations has important implications for theory, research, policy, and intervention. We begin our study with an integrative review of the applied victimization research literature, including existing meta-analyses and systematic reviews. These studies are based mainly on a unidimensional perspective in a few developed, OECD countries. This limited scope undermines the generalizability of the results to other countries and fails to account for multiple (relational, verbal, and physical) components. We posit a tripartite model and the need to distinguish between multiple (relational, verbal, and physical) components of victimization. We then test the cross-national generalizability of this model (594,196 fifteen-year-olds; nationally representative samples from 77 countries), comparing it to competing (one- and two-component) victimization models.

Dimensionality

Dimensionality: Unidimensional, Bivariate, and Tripartite Models of Victimization

Is victimization best represented by a single global component (unidimensional model), two components (a bivariate model), or three components (a tripartite model)? Marsh et al. (2011) argued that resolving this issue is critical for understanding victimization. However, the issue is tricky because victimization studies often include items that explicitly refer to physical, social–relational, and verbal victimization. In this sense, our focus on a tripartite model is not new and is consistent with a long history of research. Nevertheless, other research typically ignores the multiple components and reports only a global victimization score. This is often done without any formal reasoning for the aggregation of the scores. Almost no victimization research formally tests the factor structure of their measures based on a unidimensional model, nor do they report on each of the multiple components. For example, the widely used revised-Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire (ROBVQ) contains items referring to the different components but only reports single global scores—one for bullying and one for victimization. Roberson and Renshaw (2017) addressed this issue in a factor analysis of the 22 items in the widely cited HSBC. The HSBC items assess specific bullying behaviors. However, the Roberson and Renshaw factor analyses only identified two latent factors: a global bullying factor and a global victimization factor.

Juvonen and Graham (2014), in their influential annual review summary of bullying and victimization research, emphasized that the different components are so highly correlated that it is difficult to support their differential validity. This seems to support a unidimensional approach. However, Juvonen and Graham further noted that different victimization components are relevant to prevalence, gender differences, age-related developmental differences, characteristics of bullies (e.g., social skills and self-regulation), and the design of interventions. This seems to support multidimensional models. However, this implicit contradiction reflects the poor measurement in most applied victimization and bullying research.

In contrast to implicit unidimensional models, other researchers argue for two- or three-dimensional models. For example, Casper and Card (2017) posit a bivariate or dichotomous model. The two components are relational and overt victimization; overt victimization combines the physical and verbal components. Marsh et al. (2011, 2022; also see Bear et al., 2014) argue for a tripartite model that distinguishes between physical, relational, and verbal components. We contend that support for unidimensional models stems from inappropriate (unidimensional) theoretical models of victimization and poor measurement.

Need for Good Measurement

At the heart of the dimensionality issue is the need for good measurement. Indeed, the poor psychometric quality of measurement is a widely recognized limitation of victimization research (see reviews by Card and Hodges, 2008; Casper and Card, 2017; Gumpel, 2008; Marsh et al., 2011; Reeve et al., 2008; Rigby, 2007; Roland, 2000). Thus, Marsh et al. (2011, p. 701) concluded, “existing research posits multiple dimensions of bullying and victimization but has not identified well-differentiated facets of these constructs that meet standards of good measurement: goodness of fit, measurement invariance, lack of differential item functioning, and well-differentiated components that are not so highly correlated as to detract from their discriminant validity, and substantive usefulness in school settings.” This poor measurement quality and inconsistent use of different instruments undermine systematic reviews and meta-analyses of victimization research.

In addressing this issue, Marsh et al. (2011) demonstrated that responses to their six-factor Adolescent Peer Relations Instrument (APRI; verbal, relational, and physical facets of bullying and victimization) had strong psychometric properties that generalized over gender, age, and measurement occasion. Similarly, the six-factor Student Survey of Bullying Behavior (Varjas et al., 2006; Varjas et al., 2009) includes 24 items to measure verbal, relational, and physical components of bullying and victimization. In each case, students responded to different measures designed to measure three victimization components (being the recipient of bullying behaviors) and parallel items that measured parallel components of bullying (being the perpetrator of bullying behaviors). The Delaware Bullying Victimization Scale (DBVS; Bear et al., 2014) was adapted from the APRI. The DBVS measures six factors (physical, verbal, and social/relational dimensions of bullying and victimization). Factor analysis supported the tripartite model of bullying and victimization and the invariance of solutions over primary, middle, and high school grade levels, gender, and ethnicity. Hence, there is clear evidence that three components of victimization can be identified with appropriate measurement tools. These results suggest that victimization is a multidimensional construct with physical, verbal, and relational components.Footnote 1 It is also interesting to note that the verbal component of these instruments was more highly correlated with relational than physical components. This calls into question combining the verbal and physical components to form overt victimization as posited in the bivariate model used in many victimization studies.

Need for Appropriate Statistical Tools

A common concern in victimization research is that even when multiple victimization components are identified, they are so highly correlated that they cannot be differentiated (Juvonen & Graham, 2014). Part of the problem is poor measurement quality. However, there are also issues with the appropriate statistical tools. Most previous factor analyses in victimization studies are based on traditional confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) models. However, Marsh et al. (2011) noted these traditional CFA models do not allow cross-loadings of items (CFA’s independent cluster assumption). Hence, they typically fit the data poorly and positively bias correlations among factors, detracting from support for discriminant validity.

For this reason, Marsh and colleagues argued for the importance of exploratory structural equation modeling (ESEM; Marsh et al., 2014; Marsh, Guo, et al., 2020c) to evaluate the dimensionality of bullying and victimization. Hence, their ESEM improved the goodness-of-fit and also resulted in systematically lower correlations among the three victimization components (correlations of .81 to .84 for CFA, .43 to .52 for ESEM). Both CFA and ESEM models identified the same three components (relational, verbal, and physical victimization) for bullying and victimization responses. The difference between the two statistical approaches is that the ESEM models fit the data better, better differentiate the multiple components, and reveal the discriminant validity of the multiple components through the differential relations with critical antecedents and consequences of victimization.

To illustrate this point, we note that PISA-2019 (OECD, 2019a, b) classified the item “I was threatened by other students” as reflecting both verbal and physical components of victimization. ESEM more easily accommodates this situation than CFA. Indeed, our subsequent ESEM results show that the item loads substantially on both factors. More broadly, Xie et al. also highlighted the use of ESEM as championed in the Marsh et al. (2011) study. They noted that ESEM is a better basis for evaluating the multidimensional factor structure of bullying and victimization measures, even though it is rarely used in this area of research.

A Unidimensional Perspective of Victimization

Many applied victimization studies rely on a global or unidimensional approach, but typically without a theoretical justification. For example, in their meta-analysis on the consequences of victimization, Schoeler et al. (2018) noted that they included only one broad measure of victimization because only a few studies included different components. Similarly, Walter’s (2020) meta-analysis indicated that most studies considered victimization an umbrella term that did not differentiate between multiple components. Smith et al. (2019) evaluated victimization based on data from five cross-national surveys—including an earlier cohort of the OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA-2015) data. However, they noted that they could not evaluate the dimensionality issues, as these surveys represented victimization as a single global component. For example, the PISA cross-national studies recognize that victimization can be physical (hitting, punching, and kicking), verbal (name-calling and mocking), and relational (spreading gossip and engaging in other forms of public humiliation, shaming, and social exclusion; OECD, 2019a). However, the PISA survey contains only six items. Furthermore, in the PISA database, victimization is represented by a single global component based on responses to only three of the six items that are available in their database. Most PISA research uses only this global 3-item score, including the Smith et al. (2019) study. In summary, a unidimensional perspective of victimization is widely used. However, it is meaningful to distinguish between common practice and best practice.

Juxtaposition of Bivariate and Tripartite Models of Victimization

The bivariate model of victimization is the basis of influential and widely cited meta-analyses by Casper, Card, and colleagues (e.g., Card et al., 2008; Casper et al., 2020; Casper and Card, 2017). Consistent with our perspective, they argued against a unidimensional perspective of victimization. Instead, they contended that clarifying the extent to which different victimization components are distinct phenomena has important implications for theory, practice, and intervention. For example, Wu et al.’s (2015) meta-analysis reported emotional maladjustment (e.g., depression, anxiety, and loneliness) correlated more strongly with relational victimization than overt victimization. However, these meta-analyses and much of the research they considered focused on one or two, rather than the three, components of victimization (also see Crick & Grotpeter, 1996; Giesbrecht et al., 2011). In each case, verbal victimization was combined with physical victimization and contrasted with relational victimization. We agree that it is critical to consider victimization’s multiple components. However, in arguing for a bivariate model of victimization, Casper, Card, and colleagues (e.g., Card et al., 2008; Casper et al., 2020; Casper and Card, 2017) do not address the distinction between physical and verbal victimization. They also assume verbal victimization fits better with physical victimization than relational victimization.

Victimization research has largely ignored the tripartite model (with verbal, relational, and physical components). Although many victimization studies include items reflecting multiple components, these are typically treated as a single global measure or, perhaps, two components (overt and relational). In contrast, the tripartite model is widely recognized in bullying theory and research (e.g., Marsh et al., 2011; OECD, 2019a; Woods & Wolke, 2004; Wu et al., 2015). This tripartite model is also endorsed in reviews of aggression research (e.g., Archer, 2004). This issue is critical because, in contrast to victimization research, bullying research that evaluates multiple components routinely considers a tripartite model based on all three components. Studies have empirically highlighted the usefulness and advantages of research and the theory of using tripartite models of bullying (Marengo et al., 2019). Because bullying and victimization are two sides of the same coin, this fundamental difference in the conceptualization of bullying and victimization makes little sense. This difference in the number and nature of victimization components considered in bullying research and victimization research hinders progress in their integration and, more importantly, the development of interventions based on both research areas. Hence, the failure to differentiate among multiple components of victimization weakens understanding and the development of multifaceted interventions that address the different components. Thus, we question emphasizing a bivariate model used in victimization research. Instead, we argue for using a tripartite model of victimization and bullying and provide empirical support for this contention.

Antecedents and Consequences of Victimization: Differentiation Between Multiple Components of Victimization

We focus on evaluating the discriminant validity of the three (relational, verbal, and physical) multiple components of victimization. We follow a similar approach to Casper and Card’s (2017) meta-analysis supporting the differentiation between two components of victimization, demonstrating how they are differentially related to critical victimization correlates. However, we extend those findings to include verbal victimization as a separate, third component. The critical issue is demonstrating that all three components are distinct and differentiated in relation to critical correlates of victimization. We begin by evaluating support for this claim regarding gender and well-being. We then extend this argument in our broader discussion of attitudes towards victimization and cross-national differences in victimization. Finally, we further develop this argument with new empirical results.

Victimization and Gender

Gender is one of the most frequently studied correlates of bullying and victimization and a topic of lively debate (Juvonen & Graham, 2014). In their meta-analysis, Casper and Card (2017) reported mixed results for gender differences in victimization, partly due to inconsistent reporting of the multiple components of victimization. They found boys likelier to experience overt victimization (including physical and verbal components). Although girls experienced relational bullying more than physical bullying, gender differences in relational bullying were small. Marsh et al. (2011) found that across adolescence, boys experienced much more physical victimization (ES = − .30) and slightly more verbal victimization (− .11). However, boys did not differ significantly from girls in relational victimization. In a meta-analysis of aggression rather than victimization per se, Archer (2004) reported that physical aggression is greater for males than females across cultures and age groups, showing a peak between 20 and 30 years of age. Overall, gender differences were higher for physical aggression, smaller for verbal aggression, and negligible for relational aggression. In their systematic review of gender differences in large, cross-national surveys, Smith et al. (2019) reported that boys experienced more victimization than girls; these differences were reasonably consistent across participant ages. However, because these surveys only contained global victimization, Smith et al. could not test gender differences in distinct components of victimization. Nevertheless, Smith et al. (2019) noted valuable directions for further cross-national research: a more systematic evaluation of cross-national gender differences and their relation to country-level characteristics (level of development, educational systems, and cultural values), anti-bullying attitudes and norms, and gender-specific interventions. Here, we extend the Smith et al.’s study, pursuing these directions that they noted required further research.

Victimization and Well-Being

Victimization is associated with higher depression, anxiety, loneliness, sadness, and lower self-esteem (Kochel et al., 2012; Livingston et al., 2019; Marsh et al., 2011; Rigby and Cox, 1996). The OECD, (2019a) reported that in most countries, victims were more likely to feel sad, scared, and unsatisfied with their lives than students who were not victimized. The direction of this difference was consistent across nearly all countries. Thus, victimization is systematically related to positive and negative mental health and well-being indicators.

Our focus is on the pattern of results—the extent to which the multiple components of victimization are differentially related to well-being. Teachers, school counselors, practitioners, and victims themselves, often perceive physical victimization as the most severe form of victimization (Chen et al., 2015; Craig et al., 2000; Jacobsen & Bauman, 2007; Yoon & Kerber, 2003). However, Marsh et al. (2011) demonstrated that well-being was more correlated with verbal and relational components of victimization than the physical component for Australian students. They found, for example, that depression and internalization of anger correlated more highly with verbal (r = .38 and r = .32) and relational (r = .40 and r = .33) than with physical (r = .26 and r = .19) victimization.

Wu et al.’s (2015) meta-analysis also found relational victimization correlated more strongly to emotional maladjustment (e.g., depression, anxiety, and loneliness) than did overt (physical and verbal) victimization. In their meta-analysis, Casper and Card (2017) similarly reported that compared to physical victimization, relational victimization in adolescence correlated more strongly with internalizing problems (sadness, worthlessness, depression, worry, and fear). In contrast, physical victimization was less associated with these internalizing problems. Casper et al. (2020) noted that relational victimization correlated positively with peer rejection and negatively with peer acceptance and sense-of-belonging. However, as noted earlier, these meta-analyses combined physical and verbal victimization; this might have reduced the distinctiveness of the pattern of relations. Indeed, Marsh et al. (2011) found that patterns of relations for verbal victimization were more similar to those for relational victimization than those for physical victimization. This calls into question the appropriateness of the bivariate model compared to the tripartite model.

Victimization and Anti-Bullying Attitudes

In the present investigation, we emphasize the importance of anti-bullying attitudes. Anti-bullying attitudes index the unacceptableness of bullying behaviors for individuals, groups, and countries. Thus, for instance, 88% of students from OECD countries agree that it was good to help students who could not defend themselves and was wrong to join in the bullying (OECD, 2019a).

Anti-bullying attitudes are increasingly recognized as an important outcome in intervention studies and a critical component of interventions designed to reduce victimization (e.g., Boulton & Hawker, 1999; Jiménez-Barbero et al., 2016; Marsh et al., 2011; Marsh et al., 2022; Merrell et al., 2008; OECD, 2019a; Reeve et al., 2008; Salmivalli et al., 2005, 2021; Stevens et al., 2000). Weak anti-bullying attitudes may be associated with an increased likelihood of bullying (Marsh et al., 2011). Furthermore, anti-bullying attitudes are stronger for students in high-SES families (OECD, 2019a) and for girls (Marsh et al., 2011; OECD, 2019a; Salmivalli & Voeten, 2004). OECD argued that a better understanding of anti-bullying attitudes “may help educators and policy-makers in their efforts to develop effective bullying prevention and intervention programmes” (OECD, 2019a, p. 54). Boulton et al. (2002) also argued for the importance of anti-bullying attitudes but lamented the lack of research. Therefore, pro- and anti-bully attitudes are highly relevant to the present investigation and victimization research more broadly.

Victimization and the Pro-Bully Paradox

Boulton et al. (2002; see Olweus, 1991; Slee & Rigby, 1993) found that bullies reported more pro-bully and lower pro-victim attitudes. On this basis, they suggested that it would be fruitful for future studies to address the link between bullying attitudes and behavior in greater detail. However, they did not consider the relations between victimization and anti-bullying attitudes, a focus of the present investigation.

Logically, students suffering the most from victimization might have stronger anti-bullying attitudes. Indeed, the OECD, (2019a) emphasized this relation as one of their report’s significant highlights. However, based on their global measure of victimization, the OECD reported that “students who were not frequently bullied were more likely to report stronger anti-bullying attitudes” (OECD, 2019a, p. 46). Thus, students who suffered high levels of victimization had weaker—not stronger—anti-bullying attitudes. The OECD report emphasized the importance of anti-bullying attitudes. However, the report offered no theoretical explanation for why victims of bullying had weaker anti-bullying attitudes. Nor did they note the relevance to interventions of this paradoxical relation between victimization levels and anti-bullying attitudes. Indeed, they did not even suggest that these findings were surprising, paradoxical, or counterintuitive.

Marsh et al. (2011) had previously considered correlations between attitudes toward victims and bullies and the three components of victimization and bullying (physical, relational, and verbal). Pro-bully and pro-victim factors correlated negatively with each other. In agreement with subsequent OECD, (2019a) findings, physical victimization positively correlated with pro-bully attitudes and negatively with pro-victim attitudes. However, this pattern of relations was only evident for the physical component of victimization. Pro-bully attitudes were nearly uncorrelated with relational and verbal components of victimization; correlations with pro-victim attitudes were slightly positive—not negative. However, unlike the PISA (OECD, 2019a) study, they recognized the result as paradoxical and offered a theoretical explanation for this Pro-Bully Paradox.

Marsh et al. (2011) posited that victims of physical bullying, unlike verbal or social bullying victims, identified more strongly with bullies than victims. Their empirical evidence supported their theoretical explanation, demonstrating that victims of physical bullying had not only negative attitudes toward victims but also lower levels of self-esteem and self-concept, higher levels of depression, and an external locus of control. Marsh et al. also asked respondents what they would do when encountering a bullying situation not involving themselves. Physical victimization (and physical bullying) correlated positively with actively reinforcing the bully and negatively with actively supporting the victim. Thus, when victims of physical bullying encountered a bullying situation not involving themselves, they were more likely to advocate for the bully than the victim and might become actively involved as a bully.

Furthermore, longitudinal cross-lag models of causal-ordering showed victimization and bullying to be reciprocally and positively related, particularly for the physical components. Thus, victims of physical bullying subsequently became perpetrators of physical bullying, and vice versa (Marsh et al., 2011). Hence, it appears that victims of physical victimization identify more strongly with bullies than victims and tend to become physical bullies in the future. In the present investigation, we extend this research. We evaluate the complex cross-national differences in relations between victimization and anti-bullying attitudes and whether there is cross-national generalizability for the Pro-Bully Paradox.

Cross-National Generalizability: A Complementary Alternative to Meta-analytic Tests of Generalizability

Cross-National Studies of Victimization

Victimization is an international phenomenon but published research comes largely from the US and a few other OECD, developed countries (e.g., Casper al., 2020; Casper & Card, 2017; Moore et al., 2017; Smith et al., 1999; Smith et al., 2019). This provides a weak, potentially biased evaluation of the cross-national generalizability; it also necessarily permeates meta-analyses and systematic reviews of victimization research. To address this issue, we present a cross-national approach using multilevel modeling. This provides a complementary alternative to current meta-analyses based mainly on a few developed, OECD countries.

Cross-National and Meta-analytic Approaches to Generalizability

Cross-national and meta-analytic approaches to generalizability share many features—strengths and limitations. The quality of the data and the samples’ representativeness are crucial issues in each; the sample of multiple studies in a meta-analysis and the sample of multiple countries in cross-national research (Marsh et al., 2020a, b). However, a significant challenge to generalizability based on meta-analyses and systematic reviews is an over-representation of Western Educated Industrialized Rich Democratic (WEIRD) societies (Hendriks et al., 2019). This is particularly relevant for victimization research, based substantially on WEIRD samples. In contrast, good cross-national studies are typically based on large, nationally representative samples from many countries. In this respect, cross-national generalizability provides a viable alternative to meta-analysis.

Addressing Both Limitations

Here, we address both limitations in current victimization research: dimensionality (i.e., good measurement, number of components needed, and discriminant validity in relation to antecedents and consequences) and failure to test cross-national generalizability. We do this by evaluating cross-national differences in the three components of victimization, and their relation to gender, mental health, well-being, and anti-bullying attitudes based on the PISA2018 data (large, nationally representative samples of 15-year-olds from 77 countries). We demonstrate that failure to disentangle the multiple components of victimization has important substantive implications for understanding how the multiple components of victimization differentially relate to well-being and conclusions about the cross-national generalizability of victimization findings. We show that paradoxical relations between anti-bullying attitudes have cross-national generalizability but differ as a function of victimization components. We further show that cross-national differences in victimization levels vary as a function of country-level development (and OECD status), gender, and the specific component of victimization.

In summary, there is a reasonably consistent pattern during adolescence of well-being correlating more negatively with relational than physical components of victimization. However, there is insufficient evidence for verbal victimization and how these relations between well-being and multiple victimization components generalize across different cultures. Nevertheless, this differentiated pattern of results is important because many think of victimization as primarily physical victimization. Consequently, physical victimization is the focus of many interventions and anti-bullying policies. However, relational victimization is more detrimental to well-being and mental health than is physical victimization.

The Present Investigation

Following previous research, we evaluate cross-national differences and generalizability using PISA2018 data (large, nationally representative samples from 77 countries). This cross-national approach has many advantages compared to traditional narrative literature reviews, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses. This is especially true for victimization research based mainly on a few OECD countries, particularly the USA. Extending previous systematic reviews and meta-analyses, we evaluate how cross-national differences in victimization vary across the three components (physical, relational, and verbal), anti-bullying attitudes, and gender. Following Alfonso-Rosa et al. (2020) and Smith et al. (2019), we related country-level victimization to development (e.g., OECD status, Human Development Index (HDI), education, academic achievement, and SES), good/bad behavior (e.g., corruption, homicide, and peace), anti-bullying policy, and culture.

We begin by positing an a priori set of models based on the victimization literature (e.g., Marsh et al., 2011). Alternative models (see Fig. 1) differ in the number of victimization components and the estimation procedure (CFA or ESEM). We then evaluate the cross-national generalizability of multiple components of victimization and their relation to anti-bullying attitudes, gender, and well-being (see Supplemental Materials section 1, SM : S1, for a description of variables considered). Based on these broad aims, we posit four research hypotheses with a sufficient basis for making a priori, directional predictions based on theory or prior research. Finally, we pose three additional research questions concerning cross-national generalizability, where there is insufficient information to make a priori, directional predictions, but are nevertheless consequential issues.

Five alternative structural models relating six victimization items. Note: five-factor structure models relating six victimization (V1–V6; P: physical; V: verbal; R: relational) items to one (model 1), two (models 2 and 3), or three factors (models 4 and 5). Models 3 and 5 are ESEM models that allow cross-loadings. The single verbal victimization item is shaded in gray

Dimensionality (Hypothesis 1)

Based on our literature review, we begin by testing five alternative structural models of victimization (see Fig. 1).

-

Model 1 is a one-component model with a single, global victimization component. It is consistent with how victimization is represented in many applied victimization studies.

-

Model 2 is a two-component CFA model with physical and relational components (with verbal victimization as part of the physical component). It is consistent with distinctions made in classic meta-analysis reviews of victimization research (e.g., Casper & Card, 2017).

-

Model 3 is a two-component CFA model with physical and relational components (with verbal victimization as part of the relational component). It tests the Casper and Card (2017) assumption that the verbal component should be combined with the physical component rather than the relational component when considering only two components.

-

Model 4 is a three-component CFA model with separate physical, relational, and verbal components. It tests the claim that three components are needed.

-

Model 5 is a three-component ESEM model with separate physical, relational, and verbal components. It tests Marsh et al.’s (2011) claim that ESEM provides a better fit to the data and better differentiation of the components.

We hypothesize that Model 5 (Fig. 1) will fit the data best. Following Marsh et al. (2011), we posit that ESEM (model 5) offers better differentiation among the three components (i.e., smaller factor correlations) than the corresponding CFA (model 4). Additional support for model 5—and the need to differentiate between the multiple components—is posited to come from the differentiated relations of the three components with gender (hypothesis 2), well-being (hypothesis 3), anti-bullying attitudes (hypothesis 4), and cross-national differences (research questions 1, 2, and 3).

Gender Differences (Hypothesis 2)

Gender differences vary systematically across the three components of victimization. Compared to boys, girls will experience less physical and verbal victimization. However, gender differences will be negligible for relational victimization. Consequently, support for hypothesis 2 also supports hypothesis 1. We leave as a research question whether these gender differences are cross-nationally generalizable (see research questions 1 and 2).

Well-Being (Hypothesis 3)

In the next stage of our analyses, we considered positive and negative well-being indicators (positive/negative affect, fear of failure, overall life satisfaction, sense-of-belonging, and eudaimonia). We predict that victimization correlations (negative for positive outcomes and positive for negative outcomes) will be larger for relational and verbal victimization than for physical victimization (Marsh et al., 2011). In particular, we expect sense-of-belonging to be most negatively related to relational victimization (Casper et al., 2020; also see Goldweber et al., 2013). We further hypothesize that controlling for a set of background covariates (i.e., SES, OECD status, achievement, gender, age, year in school, home language, repeating a year in school, emotional support from parents, and changes in educational circumstances) will have relatively little effect on this pattern of results.

Anti-Bullying Attitudes (Hypothesis 4)

We hypothesize that physical victimization correlates negatively with anti-bully attitudes (Marsh et al., 2011). Thus, the more a student experiences physical victimization, the weaker their anti-bullying attitudes will be. However, this relation with anti-bullying attitudes will be limited chiefly to the physical component of victimization, not the verbal and relational components (see Marsh et al.’s theoretical rationale for why physical victims self-identify more with bullies than other victims). Hence, support for hypothesis 4 also supports hypothesis 1. In addition, consistent with other research (e.g., Marsh et al., 2011; Rigby, 2007; Salmivalli and Voeten, 2004), we expect anti-bullying attitudes to be substantially stronger for girls than for boys. We leave as a research question whether these differences associated with anti-bullying attitudes are cross-nationally generalizable (see Research Questions 1 and 2).

OECD/Non-OECD Differences (Research Question 1)

A limited amount of research suggests that victimization is higher in less developed, non-industrialized countries (e.g., Alfonso-Rosa et al., 2020; Craig et al., 2009; OECD, 2019a). However, there is little research on how cross-national differences vary across the three components of victimization, anti-bullying attitudes, and gender differences in victimization. Given the focus of the PISA research on OECD and non-OECD countries (OECD, 2019a), we first evaluate OECD/non-OECD differences in victimization. Based on previous research, we expect that victimization will be higher in non-OECD countries but leave as a research question as to how their difference varies for the different victimization components.

The evaluation of cross-national gender differences and the pursuit of gender equality is a major goal of the OECD (e.g., OECD, 2016, 2019b). Hence, it is also relevant to evaluate how gender differences in victimization differ in OECD and non-OECD countries, and how they vary as a function of the multiple victimization components and countries. Understanding these differences is also fundamental to informing the development of effective interventions.

Cross-National Generalizability (Research Question 2)

The dichotomous (OECD/non-OECD) variable is only a rough representation of country levels of development. Furthermore, the OECD’s expansion includes some additional countries that are less industrialized than some non-OECD countries. Hence, we sought additional correlates of country-level differences across all 77 countries in the three components of victimization, anti-bullying attitudes, and gender differences. Extending the Alfonso-Rosa et al. (2020) study, we evaluate how HDI and associated indicators of country-level development (country-average academic achievement and SES) correlate with country-level differences in the multiple components of victimization. We supplement our analyses of country-level correlates of victimization with additional country-level variables of societal indices of good and bad behavior (criminality, corruption, and peace; see SM : S1 for further discussion).

We also related country-level differences in victimization to Hofstede’s (2011) set of six cultural values. Hofstede’s (2011) cultural dimensions theory is a widely used cross-cultural framework of the effects of a society’s culture on the values of its members and how these values relate to behavior. In Supplemental analyses, we explored how Hofstede’s six cultural values are related to country-level victimization factors (see SM : S1 for further discussion of the six dimensions).

Anti-Bullying Policies (Research Question 3)

PISA2018 collected data on anti-bullying policies at the country level for the first time since its inception. PISA (OECD, 2019a, b) noted that developing and implementing an appropriate policy is critical for tackling bullying. More generally, the development of a robust anti-bullying policy and associated governmental legislation is widely recommended as a central component of successful intervention programs (e.g., Bauman et al., 2008; Else-Quest et al., 2010; Smith et al., 2008; Smith et al. 2012; Sullivan, 2010). However, previous research has produced mixed results (Hall, 2017; Llorent et al., 2021; Smith et al., 2012). Furthermore, we know of no previous studies based on cross-national measures of policy development and implementation. Given this broad interest but mixed results, we leave as a research question whether country-level policy development is related to country-level differences in victimization.

Methods

Samples

The PISA2018 data are based on nationally representative samples from 77 countries (594,196 fifteen-year-old students). Students anonymously completed material assessing their reading, math, and science knowledge and skills; student and family background variables; and a variety of psychosocial variables—including measures of victimization. The OECD-PISA website (https//www.oecd.org/pisa/pisaproducts/) provides public access to the data used here—including extensive documentation, theoretical rationale, and psychometric support for the variables and their invariance over multiple countries (also see SM:S1 on PISA’s quality control system). PISA2018 data are based on a complex, two-stage sampling design of nationally representative samples after using the appropriate survey weights from the public database (OECD, 2019a). We excluded three of the 80 countries (Israel, Lebanon, and North Macedonia) because student victimization data were not available from these countries.

Variables

All variables used in the present study are documented more fully in section 1 of Supplemental Materials (SM : S1), where we present components and items designed to measure each variable and fit indices for different models (SM : S2; also see OECD, 2019a, for further information on the psychometric properties and extensive documentation for measures available as part of the PISA database).

Victimization

PISA represents the three (relational, verbal, and physical) components of victimization with six items: “other students left me out of things on purpose” (relational), “other students spread nasty rumors about me” (relational), “other students made fun of me” (verbal), “I was threatened by other students” (verbal/physical), “other students took away or destroyed things that belong to me” (physical), and “I got hit or pushed around by other students” (physical). Responses to all six items are available in the PISA database. Nevertheless, OECD, (2019a) used only three of these items (other students left me out of things on purpose, other students made fun of me, and other students threatened me) to construct a composite victimization variable labeled “being bullied.” This reflects a global approach to victimization and is the basis of most PISA victimization studies (e.g., Smith et al., 2019). In contrast, however, we use all six items to evaluate the structure of victimization in competing structural models (see Fig. 1).

Positive and Negative Indicators of Well-Being

We present scales and wording of items used to represent mental health and well-being constructs in Supplemental Materials 1. Individual items and scale scores are provided in the PISA database (OECD, 2019a) to represent positive and negative well-being indicators. Single-item variables were individual positive (happy, lively, proud, joyful, and cheerful) and negative (scared, miserable, afraid, and sad) affects (also see Karademas, 2007, discussion on ‘positive’ and ‘negative’ well-being). Students were asked “In thinking about yourself and how you normally feel” how often they feel each of these positive and negative items. In the PISA database, three of the positive-affect items (joyful, cheerful, and happy) were combined to form a construct labeled “subjective well-being.” However, because the negative effect items did not fit into a single factor, OECD did not include a composite variable of negative affect (OECD, 2019a). Nevertheless, we considered each of the nine affects as separate outcomes. We also included additional scale scores of well-being constructs that were included in the PISA database: sense-of-belonging (e.g., “I feel like I belong at school,” “I feel lonely at school”), eudaimonia (e.g., “my life has a clear meaning or purpose”), a single-item rating of overall life satisfaction, and the negative effect of fear of failure (e.g., “when I am failing, I am afraid that I might not have enough talent”).

Anti-Bullying Attitudes

We assessed anti-bullying attitudes with five items (“it is a wrong thing to join in bullying,” “it irritates me when nobody defends bullied students,” “it is a good thing to help students who can’t defend themselves,” “I feel bad seeing other students bullied,” and “I like it when someone stands up for other students who are being bullied”). We posited these items to represent a separate factor that do not cross-load with the victimization factors.

Background/Demographic Variables

We also considered a diverse set of covariates available in the PISA database. In the present investigation, we used them as control variables, evaluating whether their inclusion altered the pattern relations between victimization and outcomes, particularly well-being. These covariates included gender, age, year in school, SES and achievement (at the individual student, school, and country levels), OECD vs. non-OECD (a simple dichotomous variable), number of previous changes in schools, perceived parental support, and home language (see SM : S1). In PISA2018 (OECD, 2019a), SES is a composite index of economic, social, and cultural status based on parents’ highest occupational status, highest educational level, and home possessions (including educational resources and the number of books). In addition, we considered a total achievement score reflecting the average achievement in reading, math, and science (see OECD, 2019a). We also aggregated SES and achievement to the level of the school (L2) and country (L3) and standardized (M = 0 and SD = 1) responses separately at each level.

Statistical Analyses

Factor Analyses

We tested the factor structures in models 1–5 (Fig. 1) using CFA (models 1–4) and ESEM (model 5). Following Marsh et al. (2011) and recommendations by Xie et al. (2022), we note that ESEM integrates the best aspects of CFA/SEM and traditional exploratory factor analysis. ESEM provides confirmatory tests of a priori factor structures and incorporates nearly all the features of CFA and SEM analyses. We evaluated goodness-of-fit with fit indices that are relatively sample size independent, using standard goodness-of-fit criteria (Hu & Bentler, 1999; Marsh et al., 2004a; Marsh et al., 1996). Population values of the Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), and comparative fit index (CFI), vary along a 0-to-1 continuum; values greater than .90 and .95 typically reflect acceptable and excellent fits to the data, respectively. Values smaller than .08 and .06 for the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) support acceptable and good model fits. The standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) has a lower bound of zero, and values less than .08 are typically considered an acceptable fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999). However, Marsh et al. (2004b) emphasized that these cut-off values constitute only rough guidelines rather than “golden rules.”

We used Mplus 8 (Muthén & Muthén, 2017) for all analyses. We used the robust maximum likelihood estimator (MLR), which is robust against violations of normality assumptions. Here, we applied the full information maximum likelihood method (FIML; Enders, 2010) to fully use students’ data with missing responses. FIML results in trustworthy, unbiased missing value estimates (Enders, 2010). We used the Mplus complex design option to adjust standard errors for the nesting of students within schools and countries (Muthén & Muthén, 2017).

In the present investigation, the sample sizes are so large that standardized effect sizes (ESs) as small as .01 are statistically significant, even if too small to be substantively meaningful. There is no explicit agreement on what constitutes meaningful ESs. However, Else-Quest et al. (2010; Hyde, 2005) argued that ESs < .10 are negligible and close to zero, even if statistically significant. However, while arguing for a gender similarity hypothesis, Hyde (2005) notes that most gender differences are small or near zero. Hence, particularly relative to research on gender differences, ESs > .10 and larger might be considered meaningfully large compared to the population of gender differences. Relatedly, we note that based on a review of ESs typically found in meta-analytic research, Gignac and Szodorai (2016) proposed correlations of .1, .2, and .3 as more appropriate benchmarks for demarcating small, moderate, and strong effects. Furthermore, for present purposes, we are particularly interested in the directions and sizes of differences associated with multiple components of victimization as well as the absolute values of the differences.

We began by testing the a priori models based on the victimization literature (see Fig. 1) to test hypotheses 1 (dimensionality), 2 (dimensionality in relation to gender differences), and 4 (dimensionality in relation to anti-bullying attitudes). To test hypothesis 3, we added a set of well-being indicators to these models. We evaluated results based on latent correlations relating the victimization components to these correlates and controlling these correlations for the 11 earlier listed covariates.

Next, we pursued research question 1 with SEMs contrasting four groups in a latent variable ANOVA. The groups represent combinations of country type (1: OECD, 0: non-OECD) and gender (1: female, 0: male). Using the Mplus model constraint function, we constructed contrast variables to represent the main effects of OECD and gender, the OECD-by-gender interaction, and the simple main effects (i.e., the effect of one independent variable within one level of a second independent variable).

In pursuit of research question 2, we conducted a multigroup analysis in which the country was the grouping variable. For this model, factor loadings and intercepts were constrained to be invariant over countries, allowing us to evaluate country-level means. The fit of this highly constrained model was good (RMSEA = .044, CFI = .947, TLI = .942, SRMR = .041). This supports the generalizability of the factor structure and the tripartite model over multiple countries. Therefore, we used this model to construct graphs of values for each country representing the three victimization components and corresponding gender differences. Finally, we related these differences to country-level correlations (see research question 2).

Results

The Dimensionality of Victimization (Hypothesis 1)

In the PISA 2018 survey, victimization is represented by six items reflecting victimization’s physical, verbal, and relational components. The alternative models (Fig. 1) vary only in the proposed structure (dimensionality) underpinning these six victimization items. In this section, we evaluate this issue of dimensionality (hypothesis 1) concerning goodness-of-fit (SM : S2) and factor structure (factor loadings and correlations, Table 1).

One Victimization Component (Global, Unidimensional Model)

Model 1 (Fig. 1, 1-component model) provides a reasonable fit to the data by absolute standards (e.g., CFI = .965, TLI = .942; see SM : S2), but one that is not as good as the subsequent models positing two or three components. All six victimization items load substantially on this global victimization component (Table 1).

Two Victimization Components (Bivariate Models)

Model 2 (Fig. 1) posits two components, a typical representation of victimization in meta-analyses. The components represent relational victimization and a physical component that combines the physical and verbal components (sometimes referred to as direct or overt victimization). The fit of model 2 (CFI = .968, TLI = .939 see SM : S2) is similar to model 1. However, the correlation between the two latent components (Table 2) is so high (r = .95) that the two components cannot be readily distinguished. This correlation, approaching 1.0, explains why the fit of model 2 is similar to that of model 1.

Model 3 (Fig. 1) also posits two components, but the single verbal item loads on the relational rather than the physical component. Model 3 provides an alternative two-component solution with the typical two-component representation of victimization in meta-analyses (model 2, Fig. 1). The fit of model 3 (CFI = .986, TLI = .974; see SM : S2) is better than models 1 or 2. Although the correlation between the two components is still very high (r = .89, Table 2), these two components are slightly better differentiated than the corresponding two components in model 2. These results suggest an alternative two-component model is more appropriate than the traditional two-component used in victimization research. However, they also highlight the ambiguous role of verbal victimization in two-component models.

Three Victimization Components (Tripartite Models)

Model 4 (Fig. 1) posits three victimization components based on CFA. Model 4 is consistent with our claim that there are three victimization components (verbal, physical, and relational) rather than two. The fit of Model 4 (CFI = .988, TLI = .975) is significantly better than models 1–3. Importantly, however, correlations among the three components (r = .66–.92) are still very high, detracting from the three components’ differentiability.

Model 5 posits three victimization components based on ESEM. Consistent with hypothesis 1, the fit of model 5 (CFI = 1.00, TLI = .999; see SM : S2) is exceptionally good, and better than for models 1–4. The three components are still highly correlated (r = .57–.77). However, the correlations are substantially lower than in the other models. Especially, the correlation between the relational and physical components (r = .62) is appreciably lower than the corresponding correlation in model 4 (r = .92) and the other models. Thus, in support of hypothesis 1, model 5 best fits the data and demonstrates the best differentiation among the victimization components).

Victimization: Gender Differences (Hypothesis 2)

In this second set of analyses, we added gender and anti-bullying attitudes to the five models considered in Table 2. Factor loadings relating victimization items to their factors are nearly identical to those in Table 1 (also see fit indices in SM : S : S2). Again, each model’s fit is good, although the fit of model 5 is still the best. Hence, we mainly focus on relations among the variables in Model 5 and gender and anti-bullying attitudes (Table 2). Substantively, our focus is on the patterns of correlations used to test our hypotheses and research question 3. We also note that because of the large sample size, standard errors for all correlations are less than .006, so even very small correlations are highly significant. Thus, we focus on the relative sizes of relations rather than statistical significance or uncertainty estimates.

Gender Differences in the Three Victimization Components (Hypothesis 2)

Consistent with hypothesis 2 and previous research, boys report being more victimized than girls in all five models (Table 2). Also consistent with predictions, boys report more physical and, to a lesser extent, verbal victimization. However, gender differences are negligible for relational victimization.

This clear pattern of gender differences in model 5 is blurred in the other models, particularly in models 1–3. Based on a global victimization component, we note that results for model 1 are consistent with the typical finding that girls are substantially less victimized than boys. However, this model fails to show how this gender difference varies for different victimization components. Two-component models (model 2 and particularly model 3) do better. However, they both fail to differentiate the larger gender gap in verbal victimization from the smaller gender gap for relational victimization. Three-component models 4 and 5 best provide a more differentiated pattern of gender differences. However, model 5 provides a stronger basis for differentiating the gender gap in relation to verbal and relational victimization. Thus, support for hypothesis 2 is stronger—and gender differences are more differentially related to the victimization components—in model 5 than in any other models.

Well-Being Differences in the Three Victimization Components (Hypothesis 3)

In the next set of analyses, we added a set of well-being indicators to model 5. The correlations between victimization and well-being (Table 3) are of substantive interest and contribute to the need to consider multiple components of victimization. Also, to facilitate the presentation of the results, we consider results based on negative indicators of well-being (i.e., a lack of well-being) separately from positive indicators (although we tested both in the same model). Finally, again, we focus on the relative size of relations because all standard errors and uncertainty estimates are so small, due in part to the large sample sizes.

Negative Well-Being Indicators

All five indicators of negative well-being (scared, miserable, afraid, sad, and fear of failure) correlate positively with all three victimization components (Table 3). Across the five indicators of negative well-being, the relations are consistently smaller for physical victimization (rs = .02 to .08; M r = .04) than for verbal (rs = .10 to .17; M r = 13) and particularly for relational (rs = .10 to .18; M r = .15). For each of the five negative effect indicators, correlations with relational and verbal victimization are larger than those for physical victimization, whereas correlations with relational were also as large or larger than those for verbal victimization, these differences were small. Furthermore, the most substantial relations with verbal and relational victimization are feeling miserable, sad, and fear of failure.

Positive Well-Being Indicators

All eight indicators of positive well-being (happy, lively, proud, joyful, cheerful, life satisfaction, belonging, and eudaimonia) correlate negatively to the victimization components (Table 3; the one exception is the zero correlation between feeling proud and physical victimization). Across the eight indicators of positive well-being, the relations are consistently less correlated with physical victimization (rs = .00 to − .12; M r = .09) than for verbal (rs = − .06 to − .25; M r = − .14) and particularly relational (rs = − .06 to − .36; M r = − .18).

For each of the eight positive effect indicators, correlations with relational and verbal victimization are more negative than those with physical victimization. Correlations with relational victimization are mostly larger than those for verbal victimization (for 7 of 8 indicators), but these differences were small. Furthermore, for both verbal and relational victimization, the negative relations were largest, particularly for sense-of-belonging (relational, − .36; verbal, − .25), life satisfaction (relational, − .19; verbal, − .16), and feeling happy (relational, − .17; verbal, − .13).

We also evaluated partial correlations controlling a large set of background/demographic variables (i.e., SES, OECD status, achievement, gender, age, year in school, home language, repeating a year in school, emotional support from parents, and changes in educational circumstances). We posited these as antecedents of victimization. Because these partial correlations were nearly the same as correlations without controls for both negative and positive well-being, they support the results’ robustness (see SM : S3). In summary, there is good support for hypothesis 3002E

Anti-Bullying Attitude Differences in the Three Victimization Components (Hypothesis 4)

Consistent with the Pro-Bully Paradox (hypothesis 4), anti-bullying attitudes correlate negatively with physical victimization (r = − .17; model 5 in Table 4). However, anti-bullying attitudes are uncorrelated with relational victimization (r = .01) and verbal victimization (r = .00). Thus, physically victimized students have weaker anti-bullying attitudes. This seemingly paradoxical pattern of results is consistent with Marsh et al.’s (2011) proposal and supports the Pro-Bully Paradox (see earlier discussion of Marsh et al.’s 2011 theoretical rationale of physical victims identifying more with bullies than other victims). However, this distinct pattern of relations is blurred in the other models. Model 1 is consistent with the OECD, (2019a) finding that victimization is negatively related to a global victimization component. However, model 1 fails to show how this relation varies for different victimization components. Thus, support for the Pro-Bully Paradox (and hypothesis 4) is stronger—and relations with anti-bullying attitudes and victimization components are more differentiated—in model 5 than in any other model.

Also consistent with hypothesis 4, girls have stronger anti-bullying attitudes (r = .20, Table 4). Indeed, the gender differences in anti-bullying attitudes are larger than gender differences for any victimization components in any of the five models (Table 2).

Comparison of OECD/Non-OECD Countries and Gender (Research Question 1)

In PISA data, PISA reports, and many PISA studies, there is a primary focus on differences between OECD and non-OECD countries. Specifically, we evaluated the main effects of female-gender, OECD/non-OECD, and their interaction for the three victimization components and anti-bullying attitudes. Regarding cross-national generalizability, the main effect of OECD/non-OECD countries and the interaction with gender are particularly interesting.

Multiple Components of Victimization

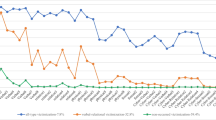

Physical and relational victimization are substantially higher in non-OECD countries (Fig. 2; also see Table 5’s OECD main effect). However, verbal victimization is only marginally higher in non-OECD countries. The main effect of gender was substantial for physical victimization, somewhat smaller for verbal victimization, and close to zero for relational victimization (see earlier discussion of results for hypothesis 2).

Graphs of marginal means represent OECD/non-OECD and gender differences. Note: a latent ANOVA (see Table 5) was used to evaluate main, interaction, and simple main effects of gender (1: female, 0: male) and OECD country (1: OECD, 0: non-OECD) in four victimization latent factors. Factor means (and their standard errors) are the deviation from the grand mean of zero (i.e., effects sum to zero across the four groups)

OECD–gender interactions are significant for all three components of victimization. However, the largest difference is relational victimization. Inspection of the latent means and simple main effects (Table 5, also see Fig. 2) shows that girls have lower physical and verbal victimization levels than boys in both the OECD and non-OECD countries. However, these gender differences were significantly larger in non-OECD countries. Moreover, not even the direction of gender differences is consistent for relational victimization across OECD/non-OECD countries. Thus, relational victimization is significantly higher for girls than boys in OECD countries, but significantly higher for boys than girls in non-OECD countries.

Anti-Bullying Attitudes

Anti-bullying attitudes were substantially stronger in OECD countries than in non-OECD countries (see Table 5, OECD main effect), and stronger for girls than boys (see Table 5, gender main effect). However, there were also gender-by-OECD interactions. Thus, girls had stronger anti-bullying attitudes than boys, and these gender differences were larger in OECD countries than in non-OECD countries. Conversely, anti-bullying attitudes were stronger in OECD than non-OECD countries, and this OECD/non-OECD difference was larger for boys than girls.

Cross-National Generalizability and Correlates of Country-Level Differences in Victimization (Research Question 2)

Country-to-Country Variation in Victimization

It is also important to note substantial variation between countries within the OECD and non-OECD classifications. Also, as noted earlier, several non-OECD countries have higher industrialization and development levels than some OECD countries. From this perspective, it is relevant to evaluate individual country-level differences. The graphs (Figs. 2 and 3) reflect this between-country variation. Thus, for example, physical and relational victimization tend to be lower in OECD countries. However, there are non-OECD countries where these two components of victimization are low (e.g., China, Belarus, and Croatia), and OECD countries where they are relatively higher (e.g., Latvia, Italy, and Colombia).

Three components of victimization and anti-bullying attitudes is country-level means and gender differences. Note: shapes in red indicate OECD countries, those in blue indicate non-OECD countries. Within the OECD and non-OECD countries, countries are ordered in relation to country-average achievement based on PISA test scores (also see Table 5). Shown are country-level means (boxes) and gender differences (lines with 95% confidence intervals)

Similarly, anti-bullying attitudes tend to be stronger in OECD countries than in non-OECD countries. However, some non-OECD countries have healthy anti-bullying attitudes (e.g., Singapore and Malta), and some OECD countries have relatively weaker anti-bullying attitudes(e.g., Latvia, Hungary, and Slovak Republic). In contrast to physical and relational victimization and anti-bullying attitudes, there is little systematic difference between OECD and non-OECD countries for verbal victimization. Again, however, there is substantial variation between countries within these classifications. Although there are OECD/non-OECD differences overall, there is also variation in victimization scores and attitudes within these two groups of countries.

Correlates of Country-to-Country Differences

Given the sizable country-to-country variation (Fig. 3; also see SM : S5 and earlier discussion of Research Question 2), we also related country-level differences to country-level correlates (Table 6). To facilitate presentation, we have divided the correlates into three groups (Table 6)—development indicators, societal indices of good/bad behavior, and Hofstede’s (2011) six cultural values. Here, we focus mainly on relations with a set of four development indices—particularly HDIFootnote 2

Development

The four country-level development indices have a reasonably consistent pattern of relations with country-level differences in levels of victimization. All four national development indices correlate positively with anti-bullying attitudes. However, they correlate negatively with physical victimization, and, to a lesser extent, relational victimization. They are almost uncorrelated with verbal victimization (also see Fig. 3).

Gender differences for each country are positively correlated with relational victimization and anti-bullying attitudes. However, these country-level gender differences are negligibly (or non-significantly) related to verbal and physical victimization. Thus, girls have more anti-bullying attitudes and experience more relational victimization in developed countries (see Fig. 3). The correlations with HDI and L3-Achievement are strongest in both levels of victimization and gender differences. However, country-level-SES and OECD also display this pattern.

Societal Good/Bad Behavior

The three societal indices reflect country-level indices of good/bad behavior logically related to victimization. These relations demonstrate that country-level indices of good/bad behavior have a different pattern of relations with each of the three components of victimization (Table 6). Perceived corruption correlates positively with physical and relational victimization and negatively with anti-bullying attitudes. Perceived corruption correlates negatively with gender differences in relational victimization and anti-bullying attitudes. The pattern of correlations with the global peace index is similar to that for corruption, but smaller in size and in the opposite direction. Country-level homicides correlate positively with relational victimization and gender differences in physical bullying but negatively with anti-bullying attitudes and gender differences in anti-bullying attitudes. Across these three indices, the largest correlations are with perceived corruption. These findings are consistent with Hong and Espelage’s (2012) social ecology perspective which we extend to include country and country-level variables.

Cultural Values

We also explored how Hofstede’s (2011) six cultural values related to country-level victimization components (see earlier discussion and SM : S1 for a description of the six values). Power–distance correlates positively with physical and relational victimization. However, power–distance correlates negatively with anti-bullying attitudes (Table 6) and with gender differences in relational victimization and anti-bullying attitudes. The pattern of relations is similar for individualism and indulgence, but in the opposite direction (negative correlations with victimization, but positive correlations with anti-bullying attitudes and gender differences). Uncertainty–avoidance correlates significantly only with levels of verbal victimization. Finally, long-term orientation correlates negatively with relational and verbal victimization, but positively with gender differences in physical victimization. Across the six cultural values, power–distance correlations were the largest, followed by individualism and indulgence. Notably, masculinity/femininity did not correlate significantly with victimization scores—not even gender differences.

National Anti-Bullying Policies in Relation to Victimization and Gender Differences (Research Question 3)

Of particular interest in the present investigation is the index based on OECD’s survey (OECD, 2019a, b) of anti-bully policies (Table 6). It might be expected that countries with a stronger anti-bullying policy framework would have lower levels of victimization. Indeed, this country-level policy index is positively related to country-level anti-bullying attitudes. However, this policy index is not significantly related to country-level victimization or country-level gender differences in victimization. In the discussion section, we explore the implications of this surprising (and disappointing) result.

Discussion

Victimization significantly impedes the development and well-being of individual students, schools, and societies. We proposed critical limitations in current research and intervention: ignoring the dimensionality of victimization and a lack of evidence on cross-national generalizability. We used PISA2018 data (large, nationally representative samples of 15-year-olds from 77 countries) to address these issues through four hypotheses and three research questions. Broadly, our results support the need to differentiate between the multiple (relational, verbal, and physical) components of victimization and demonstrate why this differentiation is important in understanding gender differences, correlates of victimization, anti-bullying attitudes, and cross-national differences. Here, we explore the implications of these results for policy, practice, intervention, and directions for further research.

One, Two, or Three Components of Victimization?

There is a curious disjuncture between bullying and victimization research literatures. Both areas rely heavily on global, unidimensional perspectives (i.e., global victimization and global bullying). However, victimization research emphasizes a bivariate model, whereas bullying research (and aggression research more generally) posits a tripartite model like that highlighted here.

Our results support and extend Marsh et al.’s (2011) contention that bullying and victimization research is best served by the tripartite model and by applying ESEM rather than CFA models. Furthermore, moving from a one- or two-component model to a three-component model also allows the victimization literature to better align with the bullying and aggression literatures that already endorse the tripartite model (Marsh et al., 2011; Woods & Wolke, 2004; Wu et al., 2015; Wu et al., 2015; also see Archer, 2004).