Abstract

Research into the benefits of underwritten issues has been conducted primarily in settings that exhibit information asymmetries between issuing firms, financial intermediaries, and investors. This paper examines, during the interwar period, an era characterized by longstanding relationships between issuers, banks, and investors, the pricing and choice of method for offering shares of Dutch IPOs. Offering method in this setting is related mainly to the volume of the issue open for subscription prior to listing. The larger the volume, the more firms tended towards an underwritten offering. The pricing is found to be unrelated to offering method as well as to variables that theoretically proxy information asymmetries. The relatively low level of underpricing largely fluctuates with past investor sentiment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Whether to use the services of an underwriter for an Initial Public Offering (IPO) recently caught the attention of the financial media with Spotify’s direct listing in 2018, and earlier with the Dutch Auction of Google in 2004.Footnote 1 From the firm’s perspective, employing an underwriter to deal with the complex and time-consuming offering and listing process frees executives to focus on running the business. Proceeds to the issuing firm, moreover, are guaranteed by virtue of the underwriter purchasing the shares at a fixed price and thereby incurring the risk that not all shares will be sold. This method seems particularly well suited to larger offerings, underwriters being more likely than an issuing firm to have close ties to a large group of investors.

This paper investigates two, according to the literature, related topics pertinent to Dutch IPOs issued during the interwar period: the method of offering shares to investors prior to listing on the Amsterdam Stock Exchange, and the pricing of shares. Fohlin (2010) having observed that an understanding of institutional circumstances is necessary to draw sound conclusions about the comparison of pricing, especially underpricing, between countries and time periods, I complement the investigation with a description of the IPO market in the Netherlands during this period.

Debate in contemporary financial literature about the benefits of underwritten IPOs is rooted in 1980s studies of underpricing that focus on the potential proceeds foregone due to shares being offered below market price. These studies are premised on the notion that price is influenced by information asymmetries between the parties to the offering process. None of these parties has all the relevant information, and those that enjoy a particular information advantage may lack other critical information. The greater the information asymmetry between issuing firm and investors, the higher the ex-ante uncertainty about the market value of shares and the greater the need to underprice the issue to assure a full placement. Shares can be offered at a higher price with an underwritten offering than with a non-underwritten offering because the financial intermediary, in its capacity as information producer, reduces the level of information asymmetry (Chemmanur & Fulghieri, 1994). However, when the underwriter has better information than the issuer about market demand for shares, the “principal-agent” model (Baron, 1982) predicts that an underwriter may exploit underpricing to optimize its revenues. In such a situation, an underwriter may, to avoid holding unsold shares, underprice an issue to such an extent as to render firms subject to a high level of information asymmetry better off employing a non-underwritten contract (Ritter, 1984, 1987). Because choice of offering method and pricing of shares may not be independent events in the IPO process, the relation between them may have implications for any investigation of these topics.

Offering volume has empirically been found to be associated with offering method. Goergen et al. (2006) find, for the UK of IPOs issued between 1991 and 1995, that underwritten contracts are used more frequently by larger firms that usually raise more money. This finding is supported by a study with historical data from the Australian market, Fleming et al. (2021) showing that underwritten issues in the interwar period generated relatively more capital. The study also found no statistically significant evidence that underwriting reduced underpricing, which the authors attribute to the institutional setting in which their investigation was conducted; with Australia’s developing stock market at the time occasioning information asymmetries, and underwriting in an embryonic stage, underwriters may have served mainly to help firms expand the range of potential investors at a time when stocks were a relatively new asset class. In contrast, Chambers and Dimson (2009), investigating a developing underwriting market from which reputational underwriters were absent, found the benefit of an underwritten IPO in the UK between 1917 and 1945 to have averaged 7.4%.

The Amsterdam Stock Exchange was well organized and among the leading exchanges in the world during the interwar period (De Vries, 1976). Many firms applied for listing, especially in the hot markets of the 1920s (De Jong & Legierse, 2021). Investors were offered shares at a fixed price with and without the services of an underwriter, and relationships between banks and firms tended to be close and long term (Van den Broeke, 1988; Jonker, 1989), as were relationships between banks and investors. These circumstances provide an opportunity to study choice of offering method and pricing for IPOs in a developed stock market with presumed low levels of information asymmetry. This was, however, also an economically turbulent period, the exuberant mood of the stock market shortly after the First World War followed by a banking crisis in the early 1920s and global stock market crash in 1929, culminating in an economic crisis and eventual abandonment of the gold standard by the Netherlands in 1936. The impact of these shocks is also part of the present study.

Analysis of 209 stock IPOs issued in the interwar period revealed the volume offered to investors prior to listing to be strongly related to offering method. Increasing volume led more firms to use the services of underwriters. I do not find evidence of either choice of method or pricing to be affected by information asymmetries between issuing firms and investors. The level of underpricing was relatively low, on average, 4.4%, and for individual IPOs independent of choice of method. Underpricing was mainly related to investor sentiment in the year prior to listing. The more optimistic investors were, the higher the level of underpricing. The economic and financial shocks seem to have had no major impact on the pricing of IPOs, but the banking crisis did influence choice of method, there being relatively fewer non-underwritten than underwritten issues before 1922 compared to the period after.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. The historical context of the Netherlands between the two world wars is reviewed in the next section. Empirical implications are derived from a theoretical framework developed in Sect. 3, with descriptive statics presented in Sect. 4. The empirical implications of the data are analysed in Sect. 5 and my conclusions presented in Sect. 6.

2 Historical Context of the Netherlands, 1918–1939

During the interwar period, firms that opened subscriptions to the public for equity issues could choose between two methods (Renooij, 1951), a non-underwritten or self-placed method termed Voor Eigen Rekening (for own account), in which the issuing firm handles both subscriptions and placement of the shares, and the method more frequently used, called Consortiaal, which involved engaging a financial intermediary to manage the issue. Issues using the latter method were often taken over by a syndicate of financial intermediaries, each member participating for a specified amount (Westerhuis & De Jong, 2015). Both methods were based on a fixed price offering and pro rata allocation of shares (pondspondsgewijs) in the event of oversubscription. With either method other banks or commissioners, so-called Guichets, could be hired to accept subscriptions and manage the allocation of shares.

Immediately following the First World War, the market for issues (for stocks and bonds) was dominated by large banks, acting either as a Guichet for self-placed issues or an underwriter for Consortiaal issues. Smaller banks ranked second, commissioners third. Due to the discontinuous nature of the issue market, underwriters were, there being no specialized investment banks, all mixed banks (Renooij, 1951, pp. 136 and 195). The dominance of large banks increased during the interwar period, their market share rising to 98% in 1939 due to firms’ ever-increasing capital needs, which further elevated requirements for financial intermediaries (Renooij, 1951, p. 201). The main banks for domestic issuing firms were Amsterdamsche Bank, Rotterdamsche Bankvereeniging, De Twentsche Bank, Nederlandsche Handel-Maatschappij and Incasso-Bank (De Vries, 1976, p. 125) and Nederlandsch-Indische Handelsbank and Nederlandsch-Indische Escompto Maatschappij for Dutch issuing firms located in the Dutch East Indies (Renooij, 1951, p. 197).

Industrial bonds and stocks were of secondary importance to institutional investors,Footnote 2 who invested mainly in Dutch and Dutch-Indies government bonds. Mutual funds played also a relatively small role, especially in the 1920s, as did small private investors (Westerhuis & De Jong, 2015). Share purchases during the interwar period were mainly by private capital owners, members of a wealthy upper-class elite that owned almost all the capital of industrial and commercial firms (Westerhuis & De Jong, 2015).

Although equity issues usually were composed of common stock, preferred shares were also popular among investors and firms in the first quarter of the twentieth century (Westerhuis & De Jong, 2015, p. 39). Holders of preferred shares were entitled to a fixed dividend expressed as a percentage of the nominal value and prioritized over other shareholders with regard to payment. This entitlement was often cumulative, that is, if annual profits did not accommodate (full) pay-out, the unpaid part of the dividend had to be made up in later years before a pay-out to other shareholders could take place, in return for which holders of preferred shares waived the right of control. Preferred shares thus enabled the issuing firm to retain full control while affording permanent capital. Over time firms learned that the right, especially a cumulative right, to a fixed dividend can become a burden in times of recession (Westerhuis & De Jong, 2015, p. 74).

A jubilant mood pervaded the Amsterdam stock exchange at the end of the First World War. With investors readily subscribing to equity issues, firms were able to raise capital effortlessly (Petram, 2016) and the stock exchange saw a wave of new listings (De Vries, 1976, p. 128). To list shares, an issuing firm needed the services of a bank, commissioner, or trader that was a member of the Vereeniging voor den Effectenhandel (De Vries, 1976, p. 147). Within 24 h of publication of a notice published in a national paper inviting investors to subscribe to an offering and stating that a request for listing was to be submitted, the member had to file an application together with the prospectus of the issue and the firm’s articles of association, balance sheet, income statement, and most recent annual report. While the application was being processed the shares could receive a preliminary listing, which would lapse upon the official listing being granted or the application rejected. Filing the application committed the firm to make its balance sheet, income statement, and annual report available to shareholders in Amsterdam and pay out dividends via the stock exchange each year.Footnote 3 The volume of the issue needed to be at least 500,000 Guilders nominal and at least ¼ of the placed capital. A price was published after actual trade in shares had occurred, stated as a percentage of the par value of one share with fractions of the price expressed in 1/16%.Footnote 4

Although listed firms were obliged to provide yearly financial statements, unlisted limited liability firms, which were considered by the Commercial Code of 1838 temporary private agreements to which contract law was applicable (Van der Heijden, 1929), were exempted from this requirement. To establish a limited liability firm required only a registered notarial deed and Koninklijke Bewilliging (royal approval) on the articles of association. The Code included some requirements for cash-based accounting, but financial statements were considered a private instrument for managing the relation between a firm and its shareholders, not a representation of true income or true capital from which the real value of shares could be derived (Camfferman, 2012). Revisions to the Commercial Code in 1928 and 1929 substituted for the Koninklijke Bewilliging a statement of Geen Bezwaar (no objection) by the Minister of Justice and required limited liability firms with more than NLG 50,000 bearer shares to annually publish a balance sheet, income statement, and report. Minimum requirements set to reinforce the significance of the disclosure of financial information applied only to the asset side of the balance sheet, no requirements being imposed on the income statement and annual report.Footnote 5 Although financial statements remained form-free and no valuation principles were prescribed, shareholders were entitled thenceforth by default to the profits reported in the financial statements (Camfferman, 2012).

Under the Commercial Code of 1838, underwriters were liable in the event financial information in a prospectus proved false. Under the revised Code, the parties that invited investors to subscribe to an issue risked being held liable under both criminal and civil law (Van Lutterveld, 1933). Those charged with the placement of shares and those who cooperated in this regard, if they knew the content of published information to be incorrect, and firm directors and supervisory boards if they deliberately disseminated misleading information, were subject under criminal law to a penalty of a maximum of three years in prison. Under civil law, anyone who, with the intent to persuade investors to buy shares on the basis of a misrepresentation of facts by publishing or having published false, incomplete or mutilated information, was liable for damages.

Because the Netherlands remained neutral during the First World War, Dutch industry was still in place at the end of the war. Except for a brief period between 1921 and 1923, strong growth in international trade fueled a booming Dutch economy until 1929. Although the momentum was such that the economy was largely unaffected by the decline of the world economy in the early 1920s (Van Zanden, 1997), that economic downturn had a significant impact on the banking sector whose rapid expansion between 1890 and 1918 (Jonker, 1996) had been accompanied by increasing concentration triggered by fierce competition and a desire for growth in combination with Dutch industry’s need for greater amounts of long-term capital (Westerman, 1920, p. 134).

Firms in the Netherlands traditionally exhibit a two-tier structure: a board of directors composed of senior management, and a supervisory board, which might include managers from other financial and non-financial firms, relatives of a firm’s founders, and other individuals. Interlocking directorates, in which a member of one firm’s board sits on a board of another firm, reflect, according to Allen (1974), a cooperative strategy for regulating the relationships between organizations that are to some extent dependent upon one another. Close personal networks that had developed between firms and banks during the First World War (Van den Broeke, 1988; Jonker, 1989) had given rise to interlocking directorates between them, many of which involved bank managers sitting on the supervisory boards of non-financial firms (Colvin, 2014). This was often the result of conditions banks set for granting substantial loans (Westerhuis & De Jong, 2015) and these loans became problematic when the economic tide turned at the end of 1920.

As a severe, sustained decline in aggregate demand and prices occasioned by falling exports put pressure on both firms and the banking sector on which they relied (Colvin, et al., 2015), many banks ran into serious problems. One of the first, Marx & Co., declared bankruptcy in April 1922,Footnote 6 and Bank-Associatie survived that year only with the support of a consortium of banks.Footnote 7 The banking crisis reached its climax in 1924 with the threatened collapse of Rotterdamsche Bankvereeniging, one of the largest banks in the Netherlands, which survived only with support of De Nederlandsche Bank (Mooij & Prast, 2002) backed by the Dutch government (Van Zanden, 1997). In total 61 banks disappeared between 1922 and 1927, 14 through bankruptcy (Mooij & Prast, 2002). A subsequent focus on liquidity made the remaining banks reluctant to provide long-term credit (De Vries, 1976, p. 125).

The stock market crash that began in New York in 1929 had a major impact on economies worldwide. The Dutch economy went into recession, with the first signs of recovery seen in 1935. The decline in stock prices on the Amsterdam Stock Exchange lasted until 1933. The disappearance of less healthy banks during the banking crisis in the first half of the 1920s may have contributed to the absence of serious financial distress during the recession in the 1930s (Mooij & Prast, 2002). Among larger banks, only Nederlandsche Handel-Maatschappij had to be reorganized in 1934 after it incurred considerable losses in the Dutch East Indies (‘t Hart, et al., 1997). The lessons of the stock market crash of 1929 that led in the United States to enact the Glass-Steagall Act in 1933 did not lead to similar regulations in the Netherlands, where the combination of commercial and investment banking continued to be permitted.

After being suspended due to the outbreak of war in 1914, the gold standard was reintroduced in 1925, at about the same time by the Netherlands and UK. The UK’s departure from the gold standard in September 1931, necessitated by a global economic crisis, precipitated a watershed of monetary policy changes around the world (Obstfeld & Taylor, 1998), prompting De Nederlandsche Bank (DNB) to decouple its monetary policy from that of the UK (Fliers & Colvin, 2022). Although already in May 1931 DNB anticipated on a possible UK departure, Sterling’s exit in September 1931 took its officials by surprise, necessitating a government bailout (Fliers & Colvin, 2022). The Dutch government subsequently held dogmatically to the gold standard until its collapse in September 1936. In an interview with a Dutch paper in 1937, former Dutch Minister of Finance Mr. P.J. Oud concluded in hindsight that the great change of September 1936 took place in a calm atmosphere.Footnote 8 This is reflected in De Vries’ (1976, p. 144) observation that when the UK and the Netherlands left the gold standard, on both occasions the Amsterdam Stock Exchange closed for only one day (respectively on the 21st of September 1931 and 28th of September 1936). With the end of the gold standard the Amsterdam stock market soared, and it was agreed that, despite some drawbacks, the depreciation of the Dutch Guilder had lifted many firms out of the mire of uncertainty and pessimism.Footnote 9

3 Theoretical Framework and Empirical Implications

3.1 Choice of Offering Method

Netherlands’ firms that issued new shares during the interwar period typically first approached investors in their network (Renooij, 1951). The size of this network being limited, the need to engage financial intermediaries with close ties to the investing public increased with the volume of offerings. Whether financial intermediaries acted as a Guichet for a self-placed offering or an underwriter depended, according to Renooij (1951), on the risks and direct costs associated with underwriting. Firms being less able to weather a failed offering when the volume is large, and the relative cost of underwriting decreasing with volume (Goergen, et al., 2006), the empirical implication is that underwritten offerings are expected to increase with issue volume.

More recent theories also link choice of offering method to indirect costs, such as the cost of underpricing. One of the fundamental models to explain underpricing is according to Lowry et al. (2017) the “winner’s curse” model (Rock,1986), which links underpricing to investor ex-ante uncertainty regarding the market value of shares occasioned by information asymmetries between issuing firms and different classes of investors. High levels of information asymmetry render assessment of firm quality and thus share value difficult for investors (Ritter, 1984). Under such circumstances, firms are likely to underprice shares in order to induce orders and minimize the risk of failing to achieve full placement of an issue. The empirical implication of the capacity of underwriters to serve as information producers, and thereby reduce the adverse impact of information asymmetries (Chemmanur & Fulghieri, 1994), is that firms are expected to be more likely to engage the services of an underwriter in the presence of a high level of information asymmetry.

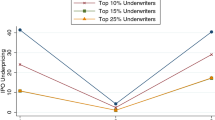

3.2 Choice of Underwriter

An issuing firm that opts for an underwritten issue must choose a (lead) underwriter. Little is known about the criteria issuers employed to select underwriters during the interwar period. Given many firms’ close ties with banks via interlocking directorates (Colvin, 2014), it is questionable whether issuers had much free choice. Models predict the choice of the most prestigious underwriter agreeing to market a firm’s equity because a high-quality underwriter signals a high-quality issue which reduces the adverse impact of information asymmetries. As a result, the proceeds will increase because underpricing can be reduced (Carter & Manaster, 1990). The proceeds, net of underwriting fees that accrue to a firm consequently increase in underwriter reputation (Chemmanur & Fulghieri, 1994). Ritter (1984) suggests market share as a proxy for underwriter reputation, but this would result in Rotterdamsche Bankvereeniging being classified as a prestigious underwriter, which, given its well documented practices, is questionable and certainly not the case in the mid 1920s (Petram, 2016, p. 138). In the absence of available data for identifying underwriter reputation, an analysis of choice of underwriter based on reputation cannot be performed.

It can be argued, because underwriters buy the shares of issuing firms before listing, that there is a positive relation between offering volume and underwriter size. Larger firms, because they need more capital, are expected to be more likely related with larger banks. Empirically, this would mean that the seven main underwriters in the interwar period are expected to be more likely to be engaged in larger firms’ higher volume issues.

3.3 Underpricing

The “winner’s curse” model (Rock, 1986) emphasizes information asymmetry between investors. When some investors are better informed than others, the less informed are faced with a ‘lemons’ problem, which is typically overcome, when both types of investors are needed to get a full placement, by underpricing. The model links level of underpricing with investor uncertainty regarding the market value of shares and homogeneity of the group of investors. An increase in volume implies a further underpricing due to the need for more less-informed investors to place orders. Level of underpricing thus needs to increase to the extent that investor heterogeneity increases with offering volume. The empirical implication is that level of underpricing is positively related to offering volume, independent of offering method.

Chemmanur and Fulghieri’s (1994) model predicts level of underpricing to be less for underwritten than for non-underwritten offerings, a consequence of the certification role of underwriters, which enables them to offer shares at a higher price by reducing the negative impact of information asymmetries between issuing firms and investors. The empirical implication is that level of underpricing is expected to be higher for self-placed than for underwritten issues.

Ljungqvist et al.’s (2006) model links underpricing and the occurrence of hot issue markets to investor sentiment. High initial returns in hot markets result when investors sell shares received prior to listing to irrationally exuberant retail investors on the first day. The empirical implication is that underpricing is expected to be related to market performance, with more ‘money left on the table’ in years in which market conditions are favorable.

Tiniς (1988) argues that underpricing also serves as an efficient form of protection against legal claims and associated damage to the reputations of both underwriter and issuing firm. Legal liabilities arise from regulations governing due diligence and disclosure requirements. The revised Commercial Code that took effect in 1928 and 1929 included new, stricter provisions on liabilities for the prospectus (Van Lutterveld, 1933). Subsequently, parties that invited investors to subscribe to an issue risked being held liable under both criminal and civil law. The empirical implication is that underpricing is expected to be higher for both self-placed and underwritten issues from 1928 onward as a mitigation measure for legal claims.

4 Descriptive Statistics

The data are described below, the statistics reported in Tables 1, 2 and sources in Table 3.

4.1 Issues and Offering Method

During the period investigated, 294 non-financial firms initially listed 320 equity issues on the Amsterdam Stock Exchange.Footnote 10 Excluded are 31 issues for foreign firms, which generally applied for a listing in Amsterdam only if they were unable to obtain the necessary capital under favorable conditions in their own countries, and for which the only option for a successful issue was an underwritten contract (Renooij, 1951, p. 206). Good firms being identifiable through exchanges’ application process (Fjesme, et al., 2021), to obtain a homogenous group of firms the issues of three firms that received a preliminary, but were subsequently denied an official listing, are also excluded.Footnote 11

At the beginning of the twentieth century firms in the Netherlands introduced a new form of takeover defence for limited liability firms intended to permanently safeguard the Dutch character of firms. A firm achieved this by founding a holding company the name of which incorporated Vereenigd Bezit, Gemeenschappelijk Bezit or Nationaal Bezit (Westerhuis & De Jong, 2015). Because an initial equity listing of such a holding is not considered an IPO for purposes of the present study in case the firm itself was already listed, 13 more issues are removed from the dataset. 49 equity issues of 44 firms received a listing after publication of a notice, but had not offered shares to investors prior to listing, resulting in these issues being excluded from the dataset owing to the absence of a pre-listing offering price. Fifteen additional issues for which no information on offering price or volume could be found in the prospectus were also excluded, resulting in a dataset with 209 issues (31 with preferred and 178 with common shares).

Which method was used to offer shares to investors prior to listing was determined from information in the prospectus as published in Van Oss Effectenboek. Similar to Rennooij (1951), issues in which the prospectus is first signed by the firm itself are considered self-placed, and all others underwritten issues. In the case of a prospectus for an underwritten issue signed by multiple financial intermediaries, the first signed name is deemed the lead underwriter for the syndicate.Footnote 12 An overview of number of issues per offering method, type of underwriter, and type of share is provided in Table 4. Reported in parentheses is the number of issues for which administrative support was hired, which occurred when investors could register at a financial intermediary other than one that signed the prospectus.

Figure 1 reports the annual number of self-placed and underwritten issues. The concentration and expansion of the banking system begun prior to the First World War, one of the factors that triggered the economic boom immediately thereafter (De Vries, 1976, p. 125), led to an increasing number of new listings that peaked in 1920, which also marked the end of the era of economic expansion and jubilation on the stock exchange. The low number of issues in 1922 and 1923 was probably the result of the banking crisis (Westerhuis & De Jong, 2015). Figure 1 also shows the impact of the stock market crash of 1929 and subsequent economic recession.

Figure 2 shows the annual nominal volumes in NLG of offered and listed shares. On average, 38% of listed shares was offered to investors prior to listing, which is consistent with the practice common at the time of first offering shares exclusively to the limited group of investors closely associated with the issuing firm (Renooij, 1951, p. 186). The exceptionally large volume of listed shares in 1920 resulted from two issues, one by Centrale Suiker Maatschappij with a volume of NLG 29 million (underwritten by a syndicate led by De Twentsche Bank), the other by Nederlandsche Maatschappij voor Scheepvaart, Handel en Nijverheid “Furness-Stokvis” with a volume of NLG 40 million (solely underwritten by Rotterdamsche Bankvereeniging). The large volume of listed shares in 1927 resulted from two issues of the same firm, Margarine Unie, both underwritten by a syndicate led by Rotterdamsche Bankvereeniging, with a total volume of NLG 51 million.Footnote 13

Table 12 in the Appendix provides an overview of the financial intermediaries ranked by the number of issues for which they were the lead or sole underwriter, offering volume and listing volume. Self-placed issues are included in the table. Rotterdamsche Bankvereeniging was the most dominant underwriter, not only in number of issues, but also in volume of offerings and listings. From 1918 to 1924 it was involved in 21% of issues (sole underwriter for 21 issues, syndicate leader for two issues, and administrative support for four issues). After 1924, the year in which it nearly went bankrupt, its involvement dropped to 13% (sole underwriter for five issues, syndicate leader for two issues, and administrative support for three issues).

4.2 Firm Characteristics

Issuing firms are classified into the following industries based on their main activity according to the Standaard Bedrijfs Indeling (CBS, 2008): agriculture, manufacturing, and commercial services. Firm age is calculated by subtracting the date on which a firm was established as a limited liability firm from the date by which investors needed to subscribe. For two firms for which the outcome of this calculation is negative, this value is set to zero.Footnote 14 Average age of issuing firms differs little between underwritten and self-placed offerings (7.86 and 8.73 years, respectively) and between offerings placed with one of the main underwriters and those placed with other underwriters (8.25 and 7.53 years, respectively).

4.3 Underpricing

Level of underpricing is calculated for each issue as the relative change in the first published price over the offering price.Footnote 15 In the 1920 and 1930s it was not unusual for the first day of trading to be several days later than the day of listing. It sometimes took years for a first price to be published; for 199 of the 209 issues in the sample a price was published within two years. The average equally weighted level of underpricing for these 199 issues is 4.4%, which level is slightly affected by a small stock effect. When underpricing is calculated as the percentage of ‘money left on the table’, the average level is 4.9%. Table 5 provides an overview of the level of underpricing.

Figure 3 reports the average level of underpricing per year. In 1922, the average level is zero. The dataset containing no issues for 1931, 1932, 1933, and 1934, no bars are visible for those years. Remarkably, the issues in 1921 and 1935 were overpriced. The relatively high level of underpricing in 1929 and 1939 (24.6 and 36.1%, respectively) resulted from two self-placed issues with common shares with underpricing greater than 100%, and the relatively low number of issues in those years (11 and 3, respectively).Footnote 16 Because Ljungqvist et al. (2006) documents underpricing to be related to investor sentiment, Fig. 3 also shows the stock market return at year-end. The relation between level of underpricing and investor sentiment is examined in greater detail in the remainder of this paper.

Figure 4, which plots the Kernel Density and normal distribution (dotted line), shows the level of underpricing to fluctuate strongly (between − 65 and + 149%). The level is negative in about 30% of issues with approximately 55% earning a positive return on the first day. The narrow peak in Kernel Density at 0 indicates that issuers and financial intermediaries were, on average, quite good at estimating the market value of offered shares.

5 Analysis of Offering Method, Underwriter, and Underpricing

5.1 Analysis of Offering Method

To check whether offering method is related to the volume of the issue offered to investors prior to listing, the natural log of OFFERING is added to the analysis. In two robustness checks this variable is replaced by the natural log of volume of the listed issue (LISTING) and the natural log of listed volume relative to the nominal size of the offering (RATIO).

It being difficult for investors to assess the quality of a firm and thus value its shares in the presence of a high level of information asymmetry, such firms could be better off using the services of an underwriter. Using firm characteristics to proxy for level of information asymmetry between issuing firms and investors receives broad empirical support (Lowry et al., 2017). Ritter (1984) maintains that the more established it is, the less difficult it is for investors to value a firm and its shares. The present study captures how established a firm is by following Ritter (1984 and, 1987) in defining two proxies, AGE and SIZE. The older and larger a firm, the more information it will have produced over the years, which can be studied by investors. In the event a firm is established before the date of incorporation and AGE therefore does not fully proxy its track record, a complementary dummy variable CONVERSION with value 1 is added. For the analyses the natural log of AGE and SIZE is used.

The information available for valuing its shares may also depend on a firm’s industry. For Dutch investors, for example, it was difficult to assess the quality and prospects of a domestic firm active in the Dutch East Indies based on the information in its prospectus.Footnote 17 Such firms, being active mainly in agriculture (known for regular crop failures) or capital-intensive oil and mining (Renooij, 1951, p. 48), were typically riskier. It therefore seems reasonable to assume that firms active in the Dutch East Indies were less likely to employ self-placement. However, according to Renooij (1951) excessively high risk associated with an issue may leave a firm with no other option than self-placement because financial intermediaries are unwilling to underwrite such issues. Effects of firm industry are captured by introducing the dummy variables INDIES for firms active in the Dutch East Indies, AGRI for firms active in agriculture, MANUFACT for firms active in manufacturing, and SERVICES for firms active in industry commercial services, without any specific expectations about their relation to offering method.

A dummy variable PREF is added to capture the effect of type of share. Having the properties of a bond and stock, preferred shares were viewed by investors as less risky (Westerhuis & De Jong, 2015). Moreover, financial intermediaries that offer preferred shares often monitored issuing firms on behalf of the shareholders via a manager on the firms’ supervisory boards. Given the perception of reduced risk together with investor preference at the time for fixed returns on investments, self-placed offerings might be expected to be more easily employed by firms that issued preferred than by those that issued common shares.

Stock market return and volatility being proxies for overall investor sentiment (Pástor & Veronesi, 2005), firms are expected to be more likely to opt for self-placed issues during periods in which investors are optimistic, that is, periods in which positive stock market returns (RETURN) and low volatility (VOLATILITY) reduce the adverse impact of information asymmetries (Choe, et al., 1993). For both variables a lag of one year is used to account for the time-consuming offering and listing process.

Dummy variable PRE-1922 is added to capture the effects of the booming economy and issue market in the period after the First World War, ending with the start of the banking crisis. Dummy variable POST-1927 is added to capture the effects of the change in liability under the Commercial Code introduced in 1928 and 1929 as well as the high uncertainty resulting from the stock market crash of 1929 and subsequent economic crisis, and the Netherlands’ and UK’s abandonment of the gold standard.

Table 6 reports the results of a bi-variate comparison of firm and issue characteristics per offering method. Note the omission of the variable AGRI owing to multicollinearity with the variable INDIES. The results, albeit insignificant, show firms that use self-placement to be, on average, smaller and issue smaller volumes.

Variables related to the choice of self-placed offering are examined via a binary logistic regression, the results of which are reported in Table 7. Because the analysis is employed with panel data, no verification on non-stationarity is performed. Model 1, which has the best fit, shows the probability of a self-placed issue to be significantly negatively related to offering volume and stock market return. The larger the offering volume, the less likely firms used the self-placed method. The negative relation with past stock market return is unexpected. There being less risk of an issue failing in booming markets, banks may have been more inclined to underwrite offerings during such periods. That fewer issues were self-placed prior to 1922, is likely due to banks’ fierce competition and pursuit of growth during this period. Issues being eagerly guided by banks (Petram, 2016), relatively less were self-placed. Choice of method is unrelated to the variables that proxy information asymmetry. A robustness check using listing instead of offering volume (model 3) confirms the significant negative relation between self-placed issues and past stock market return, and the finding that fewer issues were self-placed prior to the banking crisis. Using the ratio of volumes (model 4) confirms the significant negative relation between self-placed issues and past stock market return.

5.2 Choice of Underwriter

Table 8 presents the results of a bi-variate comparison of firm and issue characteristics per underwriter type. Differences in firm size and average values of offering and listing volume are significant. Issues underwritten by the main underwriters are, on average, larger and from larger firms.

Variables related to issues underwritten by main underwriters are examined via a binary logistic regression, the results of which, reported in Table 9, show main underwriters to be engaged more frequently in issues from larger firms but offering size to not be significant (model 1). When listing instead of offering volume is used in a robustness check (model 3), firm size is no longer significant and listing volume becomes positively significantly related. This outcome may be the result of multicollinearity between firm size and listing volume. Table 9 also shows that main underwriters less likely led a syndicate and less often hired another financial intermediary for administrative support and therefore more often acted as the sole financial intermediary.

5.3 Analysis of Underpricing

The results of an ordinary least squares regression on the level of underpricing for all issues with a price published within two years of the date of listing are reported in Table 10 (model 1). The observed level of underpricing may have been influenced by a general change in the stock market and post-listing information regarding the quality of the issuer. Because no (daily) stock market index is available to correct the observed level of underpricing, and it is not known whether material information about issuers was disclosed after listing, the analysis of model 1 is repeated with issues for which a price was published within one year (model 2), 15 days (model 3), and five days (model 4). Robustness checks for model 4 are performed with listing instead of offering volume (model 5) and the relative size of listing to the offering (model 6). The two outliers with a level of underpricing greater than 100% are excluded in models 1 to 6. The effect of this exclusion is analyzed by repeating the model 4 analysis with data that includes these outliers (model 7). Because firms can also finance through bonds, interest rates as well as market sentiment are expected to proxy for an equity investment’s attractiveness to investors. The higher the interest rate, the less attractive an equity investment and greater the need to underprice it. A negative relation is thus expected between level of underpricing and long-term interest rate (INTEREST) with a lag of one year.

Contrary to expectations, level of underpricing is not significantly related to offering method or volume. Nor does level of underpricing differ significantly between time periods, fluctuating significantly mostly with firm age and past stock market conditions. In years prior to listing in which stock market returns increased and/or investor uncertainty decreased, the level of underpricing increased. It can further be concluded from the results in Table 10 that level of underpricing is likely also related to type of share, being lower for offerings with preferred than for those with common shares. The effect of the outliers is clearly visible in model 7. Both issues being self-placed, it appears that level of underpricing is significantly related only to offering method, and higher for self-placed issues.

The results of a similar analysis with only underwritten issues, reported in Table 11, confirm the earlier results, save that share type is not significantly related to level of underpricing. Table 11 also shows level of underpricing to not be significantly affected by type of underwriter.

6 Conclusions

This paper’s analyses find choice of offering method for Dutch stock IPOs in the interwar period to be significantly related to the issue volume offered to investors prior to listing. As issue volume increased, more firms opted for underwritten offerings. This finding is consistent with Renooij (1951), who observes that Dutch firms employed non-underwritten or self-placed offerings if the risk of issue failure was sufficiently small as to not outweigh the costs associated with underwriting. Smaller volumes incurred less risk. No evidence is found that choice of offering method is related to variables that proxy information asymmetries between issuing firms and investors. My analyses further show offering method to be related to past stock market sentiment. The observed relation between positive stock market returns and fewer self-placed issues, in relative terms, may also be risk-driven. During periods when investors are optimistic, the risk of an issue failure decreases, which can make financial intermediaries more inclined to underwrite an issue.

Although not related to offering method, listed issue volume is strongly related to type of underwriter, the top seven underwriters having been more involved in larger issues of larger firms. This finding is likely the result of the long-term relationships between firms and banks, larger banks being associated with larger firms that generally issue larger volumes.

As for choice of offering method, no evidence was found that pricing is related to variables that proxy information asymmetries between issuing firms and investors. Level of underpricing was no more affected by offering method than by offering volume and was also unrelated to type of underwriter. The systematic but relatively low level of underpricing fluctuated mainly with stock market sentiment in the year prior to listing. The more optimistic investors, the higher the level of underpricing. This finding implies that the offering prices of the studied IPOs may have been consistent with their economic values and the overvaluation only temporary, attributed to the speculative appetite of investors who could not get allocations of oversubscribed issues.

The several economic shocks during this period seem to have had a major impact on the number but not the pricing of IPOs. Choice of method, however, was affected by the banking crisis, the relatively fewer self-placed issues in the period up to 1922 likely explained by banks’ eagerness to underwrite issues, driven by fierce inter-bank competition and the desire to grow immediately after the First World War. That eagerness diminished with the banking crisis.

Overall, findings are consistent with a setting characterized by low levels of information asymmetry, despite the absence of formal accounting rules, valuation principles, and legal requirements to disclose information (especially in the 1920s). The finding that underpricing is not related to offering volume could imply that investor group heterogeneity did not increase with volume. This is in line with the characteristics of this group, which consisted mainly of wealthy Dutch private investors (Westerhuis & De Jong, 2015). Institutional investors and mutual funds played a small role and the standard nominal value of NLG 1,000 for a share was probably an insurmountable threshold for many small private investors.

The present research admits some limitations. It is possible, for example, that firms traded debt before listing equity, but the role of debt and any incentives associated therewith could not be explored due to lack of data. For the same reason, the effect of interlocking directorates and inside information, which may influence choice of offering method and level of underpricing, could not be examined. Lastly, the prices at which underwriters took over issuers’ shares and whether offerings were oversubscribed may shed new light on underpricing. All of these limitations provide excellent avenues for future research.

Notes

“Spotify goes for gutsy direct listing on stock exchange – here are the winners and losers,” THE CONVERSATION, Academic rigour, journalistic flair, April 4, 2018, via https://theconversation.com/spotify-goes-for-gutsy-direct-listing-on-stock-exchange-here-are-the-winners-and-losers-94209.

DOELSTELLING EN ORGANISATIE VAN HET OVERLEG IN BELEGGINGSZAKEN, P. Steinz, May 4, 1939.

Reglement voor het opnemen van fondsen in de Prijscourant, August 1 1909, in Van Oss Effectenboek 1921 part I.

Reglement voor de Notering, November 1, 1921, in Van Oss Effectenboek 1921 part I.

Letter from Minister Donner, Ministry of Justice, in 1928 in which he answers questions raised in parliament.

Inventaris van het archief van de Marx & Co.‘s Bank, (1893) 1869–1970 (1988), Nationaal Archief, Den Haag, De Nederlandsche Bank NV (DNB), nummer toegang 2.25.77.28.

Inventaris van het archief van de Bank-Associatie, (1895) 1918–1971, Nationaal Archief, Den Haag, De Nederlandsche Bank NV (DNB), nummer toegang 2.25.77.10.

EEN JAAR LOS VAN HET GOUD, Staatkundig Gereformeerd Dagblad, 29-09-1937. Mr. P.J. Oud was Minister of Finance from May 26, 1933 to June 24, 1937 (own translation).

DOELSTELLING EN ORGANISATIE VAN HET OVERLEG IN BELEGGINGSZAKEN, P. Steinz, May 4, 1939.

De Jong and Legierse (2021) are the source of the raw data, which contains no IPOs of financials. In the case of different types of shares being issued simultaneously at some firms’ IPOs, each issue is counted separately.

Official listings were denied for Algemeene Motoren Omnibus en Vracht Auto Maatschappij, Nationaal Sportterrein ’t Langeveld, and Oliezaden Import Maatschappij.

The ranking of financial intermediaries in the prospectus reflects their interest in the syndicate. Many thanks to Ton de Graaf, corporate historian at ABN AMRO Bank, for providing this information.

One issue with a volume of NLG 13 million with preferred shares and one issue with a volume of NLG 38 million with common shares.

The calculated age of Hollandsche Kunstzijde Industrie is -150 days, that of Nederlandsche Bioscoop Trust − 139 days.

Due to lack of a price at the end of the first trading day, underpricing is calculated with Vorige Koers (previous price), which is the average of the lowest and highest price of the previous day (De Kat, 1916, p. 371).

Two outliers are (1) Nederlandsche Ford Automobielfabriek (offering: NLG 1 million; underpricing: 149%) in May 1929 and (2) Hollandsche Constructiewerkplaatsen (offering: NLG 156,250; underpricing: 102%) in June 1939. An IPO of a similar European subsidiary of Ford Motor Company on the London Stock Exchange in December 1928 recorded an underpricing of 87% (Chambers & Dimson, 2009).

As an example, Nederlandsch-Indische Handelsbank reports in 1919 that it received the information referenced in the prospectus from the firm Maatschappij tot voortzetting Der Zaken van Deutekom & Waal, active in Bandoeng, via telegraph, and states that it cannot guarantee that the information is correct.

References

Allen, M. (1974). The structure of Interorganizational Elite Cooptation: Interlocking corporate directorates. American Sociological Review, 39, 393–406.

Baron, D. P. (1982). A model of the demand for Investment Banking advising and distribution services for New Issues. The Journal of Finance, 37(4), 955–976.

Camfferman, K. (2012). A contract-law perspective on legal cases in Financial Reporting: The Netherlands, 1880–1970. Accounting History, 17(2), 141–173.

Carter, R. B., & Manaster, S. (1990). Initial public offerings and underwriter reputation. Journal of Finance, 45, 1045–1067.

CBS. (2001). Tweehonderd Jaar Statistiek in Tijdreeksen 1800–1999. Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek.

CBS. (2008, 21 July). Standaard Bedrijfs Indeling 2008, Structuur. Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek.

CBS. (2010). 111 Jaar Statistiek in Tijdreeksen 1899–2010. Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek.

Chambers, D., & Dimson, E. (2009). IPO underpricing over the very Long Run. The Journal of Finance, 64(3), 1407–1443.

Chemmanur, T. J., & Fulghieri, P. (1994). Investment banking reputation, information production and financial intermediation. The Journal of Finance, XLIX(1), 57–79.

Choe, H., Masualis, R., & Nanda, V. (1993). Common stock offerings across the business cycle. Journal of Empirical Finance, 1, 3–31.

Colvin, C. L. (2014). Interlocking directorates and conflicts of interest: The Rotterdamsche Bankvereeniging, Mueller & Co. and the Dutch Financial Crisis of the 1920s. Business History, 56(2), 314–334.

Colvin, C. L., de Jong, A., & Fliers, P. (2015). Predicting the past: Understanding the Causes of Bank Distress in the Netherlands in the 1920s. Explorations in Economic History, 55, 97–121.

De Jong, A., & Legierse, W. E. J. (2021). What causes hot markets for equity IPOs? An analysis of initial public offerings in the Netherlands, 1876–2015. European Review of Economic History, 26, 208–233.

De Kat, O. B. W. (1916). Effectenbeheer: Rechtskundig, economisch en administratief handboek. Bohn.

De Vries, J. (1976). Een Eeuw Vol Effecten, Historische schets van de Vereniging voor de effectenhandel en de amsterdamse effectenbeurs 1876–1976. Vereniging voor de Effectenhandel.

Fjesme, S. L., Galpin, N. E., & Moore, L. (2021). Rejected stock exchange applicants. Journal of Financial Economics, 139(2), 502–521.

Fleming, G., Liu, Z., Merret, D., & Ville, S. (2021). Underpricing in a developing Capital Market: Australian equity issuances 1920–1939. The Economic History Review, 0, 1–25.

Fliers, P. T., & Colvin, C. L. (2022). Going Dutch: Monetary policy in the Netherlands during the interwar gold standard. Financial History Review, 29.2, 121–151.

Fohlin, C. (2010). Asymmetric information, market power, and the underpricing of new stock issues in Germany, 1882–1892. The Journal of Economic History, 70(3), 630–656.

Goergen, M., Khurshed, A., & Mudambi, R. (2006). The strategy of going public: How UK Firms choose their Listing contracts. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, 33(1&2), 79–101.

Jonker, J. (1989). Waterdragers van het kapitalisme; nevenfuncties van Nederlandse bankiers en de verhouding tussen bankwezen en bedrijfsleven, 1910–1940. Jaarboek voor de geschiedenis van bedrijf en techniek, 6, 158–190.

Jonker, J. (1996). Between private responsibility and public duty: The Origins of Bank Monitoring in the Netherlands, 1860–1930. Financial History Review, 3, 139–152.

Ljungqvist, A., Nanda, V., & Singh, R. (2006). Hot Markets, Investor sentiment, and IPO pricing. The Journal of Business, 79(4), 1667–1702.

Lowry, M., Michaely, R., & Volkova, E. (2017). Initial public offerings: A synthesis of the literature and direction of Future Research. Foundations and Trends in Finance, 11(3–4), 154–320.

Mooij, J., & Prast, H. M. (2002). A Brief History of the Institutional Design of Banking Supervision in the Netherlands, Research Memorandum Wo no. 703/Research Series Supervision no. 48, October 2002.

Obstfeld, M., & Taylor, A. M. (1998). The great depression as a watershed: international capital monility over the long run. In M. Bordo, C. Goldin, & E. White (Eds.), The defining moment: The Great Depression and the American Economy in the Twentieth Century. National Bureau of Economic Research/University of Chicago.

Pástor, L., & Veronesi, P. (2005). Rational IPO waves. The Journal of Finance, 60(4), 1713–1757.

Petram, L. (2016). De Vergeten Bankencrisis. Uitgeverij Atlas Contact.

Renooij, D. C. (1951). De Nederlandse Emissiemarkt van 1904 tot 1939. Proefschrift Vrije Universiteit te Amsterdam, J.H. de Bussy Amsterdam.

Ritter, J. R. (1984). The hot issue market of 1980. Journal of Business, 57, 215–240.

Ritter, J. R. (1987). The costs of going public. Journal of Financial Economics, 19, 269–282.

Rock, K. (1986). Why new issues are underpriced. Journal of Financial Economics, 15(1–2), 187–212.

’t Hart, M., Jonker, J., & van Luiten, J. (1997). A financial history of the Netherlands. Cambridge University Press.

Tiniς, S. M. (1988). Anatomy of initial public offerings of common stock. The Journal of Finance, XLIII(4), 789–822.

Van den Broeke, W. (1988). Vermogensstructuren en netwerkrelaties in het nederlandse bedrijfsleven 1890–1940. Jaarboek voor de geschiedenis van bedrijf en techniek, 5, 154–171.

Van der Heijden, E. (1929). Handboek voor de Naamlooze Vennootschap naar Nederlandsch Recht. Tjeenk Willink.

Van Lutterveld, W. M. J. (1933). Effecten. Van Stockum.

Van Zanden, J. L. (1997). Een Klein Land in de 20e Eeuw, Economische Geschiedenis van Nederland 1914–1995. Het Spectrum.

Westerhuis, G., & De Jong, A. (2015). Over Geld en Macht: Financiering en Corporate Governance van het Nederlandse Bedrijfsleven. Boom.

Westerman, W. M. (1920). De Concentratie in het Bankwezen, Een Bijdrage tot de Kennis der Economische Ontwikkeling van onzen Tijd. Martinus Nijhoff.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Jutta Bolt, Peter Koudijs, Peter Roosenboom, Abe de Jong, Mathijs van Dijk, and two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments. Many thanks also to Ton de Graaf for granting access to ABN AMRO Bank archives and providing additional information.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author has no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Legierse, W. Offering Method and Pricing of IPOs: An Analysis of Stock IPOs in the Netherlands, 1918–1939. De Economist 171, 207–238 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10645-023-09422-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10645-023-09422-2