Abstract

Using representative survey data on the Dutch population, we analyze households’ actual participation and stated preferences for crowdfunding involvement at the extensive and intensive margin, with emphasis on the relation with investing in socially responsible assets. We find that crowdfunding investors are higher educated and more future oriented than others, whereas risk aversion plays a negative but insignificant role. Financial literacy is positively associated with knowing about crowdfunding, but not with actual participation. A stated choice preference experiment largely confirms these relations. At the intensive margin, however, results are rather different: Women have a stronger preference for crowdfunding than men do. Financial literacy reduces the preferred share invested in crowdfunding. We find a strong positive relation between crowdfunding and socially responsible investing. We identify several common factors: a desire to contribute to improving society and a lack of confidence in traditional financial institutions. Comparing stated and revealed preferences, we find that the potential for attracting more crowdfunding funders is much smaller than for attracting socially responsible investors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The term crowdfunding refers to the issue of an entrepreneur obtaining external financing from a large number of people, usually conducted through an internet-based platform. This comes as an alternative to the traditional financing methods where a limited number of investors would provide the necessary financial resources, as in crowdfunding every member of the “crowd” is supplying a small part of the total amount that is needed (Belleflamme et al., 2014).

Crowdfunding is an increasingly popular financing channel, reaching a funding volume of 16.2 Billion US $ worldwide in 2014 (Massolution, 2015). According to the report by U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, after relaxing regulations, crowdfunding has raised approximately $108.2 million during 2016–2018. In the U.K., this amount is even larger.Footnote 1 While crowdfunding platforms are popular across the globe, Ilzuka (2014) assessed that around 60% of the world’s crowdfunding platforms (CFPs) were created in Europe, with the UK leading in terms of financing volume: approximately 2.3 billion Euros in 2014. France, Germany and Sweden follow the UK as nations where crowdfunding is gaining popularity.

The recent growth of the crowdfunding market has drawn some attention in academia. Many empirical studies analyze the relation between characteristics of the project or the entrepreneurs and the success of the project. On the other hand, there is a lack of studies on what drives individuals and private households to participate in crowdfunding and become “funders.” This paper contributes to filling in this gap, evaluating funders’ socio-economic characteristics using a representative sample of private households in the Netherlands. It aims at analyzing the interest of the Dutch population in crowdfunding, and at determining the characteristics of potential crowdfunding investors. The actual and potential interest in crowdfunding is estimated with questions on actual crowdfunding investment as well as hypothetical investment scenarios where crowdfunding is one of the investment options. Finally, the paper also evaluates the connection between the interest in crowdfunding and the interest in socially responsible (SR) investments and identifies common factors that explain the positive relation between preferences for the two types of alternative investments.

In the Netherlands, the crowdfunding market is relatively small in absolute terms when compared to the ones from UK or US, but the number of crowdfunding platforms per million of residents was the highest among 15 EU countries in 2014 (Dushnitsky et al., 2016, Fig. 1b). Moreover, its size has been increasing fast in the last few years: In 2011, the total value of crowdfunding transactions was around 2.5 million Euros (see Louisse, 2018), growing to 14 million Euros in 2012, and 424 (see Editorial Team, 2020). Million Euros raised in 2018. The growing EU interest in crowdfunding is also illustrated by the Fintech Action Plan presented by the European Commission (European Commission, 2018), with a chapter dedicated to crowdfunding. This aims at creating a single European-wide license for crowdfunding platforms, to be granted by the European Securities & Markets Authority (ESMA) with the purpose of harmonizing the crowdfunding market throughout the EU. Thus beyond research reasons, it is of great help for the seekers of funding to know the characteristics of potential crowdfunding funders.

We find that crowdfunding investors are higher educated and more future oriented than others, whereas risk aversion plays a negative but insignificant role. Financial literacy is positively associated with knowing about crowdfunding, but not with actual participation. A stated choice preference experiment largely confirms these relations. At the intensive margin, however, results are rather different: Women have a stronger preference for crowdfunding than men do, and financial literacy reduces the preferred share invested in crowdfunding.

Considering both stated and revealed preferences, we find a strong positive relation between crowdfunding and socially responsible investing. We identify several common factors: a desire to contribute to improving society and a lack of confidence in traditional financial institutions. Comparing stated and revealed preferences, we find that the potential for attracting more crowdfunding funders is much smaller than for socially responsible investors.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Sect. 2 assesses the literature regarding crowdfunding while Sect. 3 describes the data. Section 4 presents the results of the empirical analysis of stated and revealed preferences for crowdfunding. The paper ends with conclusions and further research recommendations in Sect. 5.

2 Literature Review

Belleflamme et al. (2014) define crowdfunding as follows: “Crowdfunding involves an open call, mostly through the Internet, for the provision of financial resources either in the form of donation or in exchange for the future product or some form of reward to support initiatives for specific purposes.” Three types of crowdfunding projects (CFPs) are distinguished: donation-based, reward-based, lending-based, and equity-based crowdfunding (Ahlers et al., 2015). Donation based projects are usually created to support certain artistic or humanitarian projects. There are no in-kind payments towards the funders or other returns except the recognition within the community for sponsoring the specific project. For the other types, investors receive compensation for their investments. These other three types, where funders (“backers”) participate with the perspective of getting a return, can be categorized as incentive-based crowdfunding (Bretschneider and Leimeister, 2017). This is the type of crowdfunding we will investigate in this study.

There are many studies regarding crowdfunding in the literature: some focus on the geography of crowdfunding (Agrawal et al., 2011), the economics of crowdfunding (Belleflamme et al., 2014), the drivers of a successful campaign in obtaining financing from CFPs (Lukkarinen et al., 2016) or the role of social networks in CFPs (Vismara, 2016). Nevertheless, little work has been done on the characteristics of the backers, the individuals that invest in CFPs. Funders aim at helping entrepreneurs during an initial stage of a project or a venture by becoming investors, active consumers, or a combination of both (Belleflamme et al., 2014).

Belleflamme et al. (2014) argue that, regardless of the form of the support, funders who participate in the firm’s financing at an early stage enjoy “community benefits” and feel they are a part of a “privileged” community of investors, which increases their utility compared to regular investors who join later. As these non-monetary benefits are a crucial component in crowdfunding, the managerial decision on what type of investors the firm needs to target is vital for the success of a crowdfunding project. To help firms build the “right” community, it is imperative to find out why investors participate in crowdfunding in the first place.

Gerber et al. (2012) also support the idea that the desire to become part of a community that shares similar ideals and interests is one of the main motivations to participate in crowdfunding, along with financial compensation and the intention to help others. Philanthropic motives are also highlighted by Ryu and Kim (2016). They find that older people who score high on the personality characteristic agreeableness (i.e., the degree to which someone exhibits compassion and an interpersonal orientation) are likely to be driven by altruistic motives, while young investors tend to expect higher returns, participating in lucrative projects such as art and gaming. Bretschneider and Leimeister (2017) confirm that investors have a desire to be recognized by others for their participation in crowdfunding. At the same time, they show that investors are driven by prosocial considerations in that they develop personal preferences for certain firms and invest simply because they like the venture.

Some of the motives for participating in crowdfunding are similar to those for investing in socially responsible (SR) assets. Bollen (2007) finds that SR-investors base their decisions on a multi-attribute utility function, reflecting that their utility increases not only with financial gains but also due to non-financial attributes: the socially responsible attributes themselves. Riedl and Smeets (2017) investigate the motives of SR-investors based on a sample of Dutch investors. Their results show that investors’ social preferences and social signaling, or “recognition desire” as it is called in other studies, are the major drivers of SR-investors’ financial decisions, while some investors might even forgo financial returns in order to hold socially responsible funds. This is in line with the finding that crowdfunding investors are driven by prosocial motives as well as financial compensation.

Due to the nature of crowdfunding, it is hard to compare the performance of crowdfunding investments with those of traditional investments. Signori and Vismara (2016) examine the returns on crowdfunding investments and argue that crowdfund backers could gain up to 371% if they were able to identify the “next Google”. However, if they fail to do so, there is also a 10% probability that they lose all of their investments. In this sense, crowdfunding investments have similar characteristics to initial public offerings (IPOs) in that the investors for IPOs can be subject to extreme returns.

From a psychological perspective, the literature has extensively studied the factors behind the decision of giving: Liu and Aaker (2008) attribute the decision to give to charity to sentiments such as empathy and sympathy, which ultimately increases the happiness of the funders, increasing their total welfare. On the other hand, motivated by the Identity-Based Model, Aaker and Akutsu (2009) claim that one of the more important factors in giving money to others is related to one’s identity: how one is viewing him- or herself. They find that “readiness to act” is an identity feature that is influencing the decision of giving money.

In analyzing the decision of funders to join a CFP, Gerber et al. (2012) conducted interviews with crowdfunding funders and creators. They concluded that funders have three main reasons for participating in a crowdfunding platform. The first one refers to seeking rewards, most of the times as services or products. They claim that the words used by funders in describing such transactions (“buying”, “giving” or “getting”) suggest that crowdfunding participation is influenced by both traditional consumer arguments and philanthropic behavior. Secondly, funders are also inclined to support and connect with others, by helping them to meet their goals, in order to confirm certain moral values that they behold. For instance, there is a higher chance of participating in a CFP if one’s identity includes supporting others and helping causes. Lastly, funders may also participate in a crowdfunding project in order to engage in a community, to enlarge their social network and to receive recognition of their status.

These results are consistent with Gerber and Hui (2013) who conducted interviews with participants from the most successful crowdfunding platforms in the US and found similar results. However, they also touch upon the reasons that might deter one’s decision to join a CFP. There are CFPs that allow the creators (funding seekers) to keep the amount raised even if the funding goal they had was not reached. While this is supportive for the creator, funders fear that their money will not be used effectively. Moreover, poor communication and possible delays are other reasons that inhibit funder’s participation in crowdfunding.

Nagy and Obenberger (1994) claim that demographic factors are important components when it comes to financial decision-making processes (e.g. investments, donations) with age and gender being important indicators in forecasting such a decision. Using a survey of funders of two reward-based crowdfunding platforms in South Korea, Ryu and Kim (2016) evaluated six funding motivations: reward, relationship, recognition, playfulness, interest and philanthropy. They identified four categories of crowdfunding funders: “reward hunters,” “avid fans,” “angelic backers” and “tasteful hermits.” Angelic backers are comparable with the more traditional philanthropic donors, while avid fans are similar to the members of a brand community. Reward investors are the equivalent of market investors and tasteful hermits support projects as vocally as avid fans, but also have some other motivations rather than just the pure support of the project.

Ryu and Kim (2016) investigated the personality of the funders using the Five-Factor Model for measuring personality traits. The components of the model are openness (reflecting tolerance of new ideas and flexibility in thinking), conscientiousness (indicating persistence and determination in achieving goals), extraversion (degree to which people are sociable and ambitious), agreeableness (degree to which someone shows compassion and interpersonal orientation) and neuroticism (referring emotional instability, hostility and anxiety). Ryu and Kim show that angelic backers have a high score on agreeableness and a low score on openness suggesting their involvement in projects with “generous intentions” rather than applauding innovation or pursuing their own motives. On the other hand, reward hunters present the opposite picture: low agreeableness and high openness. Concretely, angelic backers have the tendency to allocate small amounts in an early stage of a big project, whereas reward hunters pledge their resources at later stages and to smaller projects. When it comes to demographic variables, angelic backers tend to be older than reward hunters. Avid fans are the most agreeable, extrovert, open and conscientious funders. They are the group that provides the highest amount for funding. Lastly, tasteful hermits support their chosen projects as vividly as avid fans but have additional motives like relationship building and recognition.

Rodriguez-Ricardo et al. (2018) are among the few who not only consider funders but analyze the intention to participate in crowdfunding for a representative (Spanish) sample. They approach the funder decision from consumer behavior, using the perspective of Social Identity Theory (SIT), a paradigm that addressees the function and structure of the socially constructed self (the social identity of a person). They identify several traits that affect the intention to participate in crowdfunding: “interpersonal connectivity,” “attitudes toward helping others,” and “level of innovativeness.”

While the study of Rodriguez-Ricardo et al. (2018) focuses on sociological and psychological attitudes, our study focuses more on the economic arguments and the financial decisions of households considering their saving allocation and portfolio choice. We follow the approach of Rossi et al. (2019) for socially responsible investments. Rossi et al. (2019) use a representative sample of Dutch households to compare actual ownership of SR-assets with intentions to buy SR-assets elicited in a stated preference experiment. Among other things, they find that highly educated individuals have a substantial latent demand for SR-assets that is currently unexploited. They also emphasize the importance of financial literacy. We use the same source of data that they exploited. In addition to the information on SR preferences used by Rossi et al. (2019), this data set has revealed and stated preferences on participation in crowdfunding and stated choices between crowdfunding, SR-investment, or a mutual fund investing in traditional stocks.

3 Data

The data were collected through an Internet survey among participants of the CentERpanel, run by CentERdata at Tilburg University. The CentERpanel is based upon a random probability sample representative of the Dutch population—households without Internet access get the necessary equipment to participate. Approximately 2000 households participate. Household members of ages 16 and older complete questionnaires on a variety of topics. Once a year, panel members provide detailed information on many domains of life, including background information on the household’s socio-economic characteristics like income, wealth, saving behavior and saving attitudes. To correct for selective unit nonresponse, CentERdata has provided sample weights based upon education, income, gender and age.

The survey we use was conducted in May 2016 (see also Rossi et al., 2019). All 2888 individuals aged 18 or older were invited to participate, but respondents without any financial accounts or involvement in household finances (7.2% of the sample) got the stated but not the revealed preference questions. The others got all questions about actual and hypothetical socially responsible investments and crowdfunding. Most of our analysis focuses on this subsample.

We control for financial literacy and household financial wealth. These are taken from the DNB Household Survey, another survey administered to the same sample at a different point in time. Although the complete sample was invited to participate in this survey, not everyone did. Moreover, due to nonresponse, there are missing values on financial wealth. We drop 255 respondents for whom the information on financial wealth or financial literacy was not available. Combining the CentERpanel sample weights with the inverse probability weights for selection into the actual ownership question, we constructed new weights to make our descriptive statistics population representative.

3.1 Revealed Preferences

The first part of the survey has questions regarding actual ownership of SR-assets and knowledge of and actual participation in crowdfunding. The most important questions for our purposes are given below, after the following brief explanation of what is meant by crowdfunding:

Nowadays there are new investment opportunities where many people can all contribute a small amount to a specific project of their choice. You can think of cultural activities, setting up a small environmentally friendly project, or other social initiatives in society. This is called crowdfunding.

-

Q1.

Have you ever heard of crowdfunding? Yes (1)/no (0)

-

Q2.

Have you (or someone in your household) invested money in crowdfunding? Never (0)/once (1)/more than once (2)

A minority of 16.3% has never heard of crowdfunding (Q1 = 0). Among those who have heard of crowdfunding, 8% participated once in crowdfunding (Q2 = 1) and 3.4% participated more than once (Q2 = 2). This means that 9.5% of the complete sample (including those who never heard of crowdfunding) participated in crowdfunding at least once.Footnote 2 In the same sample, 8.1% of all households invest in socially responsible assets (Rossi et al., 2019). Participation in crowdfunding and ownership of SR-assets are positively related: Among SR-investors, 20.6% participated in crowdfunding, compared to only 8.6% among non-SR-investors.

3.2 Stated Preferences

In the second half of the survey, the respondents are asked to express their stated preferences for different investment possibilities of a hypothetical inheritance of €5000 or €10,000 (randomly assigned) that must be invested for a 1-year time horizon. Specifically, the following two questions involve crowdfunding:

Suppose you receive an inheritance of [5000/10,000] euros, but the condition is that you can only spend this money in a year at the earliest. You can now invest the money by putting it in an account or by investing it and receive the amount and the net proceeds one year later.

We ask you to choose what you would with the money. Please note: all possible choices are hypothetical; they are not based on the actual current returns.

-

Q3.

What would you choose if you had the following options?

-

1.

Invest the money in a fund with a return that is linked to the AEX (Amsterdam Stock Exchange) index. (The AEX invests in shares of the largest companies in the Netherlands.)

-

2.

Invest the money in crowdfunding for a social, environmental or cultural project of your choice, and with a fairly risky return.

-

3.

Invest the money in an investment fund that only invests in a carefully selected group of socially responsible companies. Compared to the AEX, this fund has on average [0.5/1.0]% lower annual return, with a comparable risk.

-

Q4.

Suppose you receive an inheritance of [5000/10,000] euros, but the condition is that you can only spend this money in a year at the earliest. Suppose you can split the amount in two and that you invest a part in a fund that is linked to the AEX, and that you invest the rest of the amount in crowdfunding. How would you divide the money?

I invest … % in the AEX investment fund; I invest …. % through crowdfunding.

In Q3, the majority (58.4%) chose the traditional investment. Most of the remaining respondents chose SR-assets (29.4% of the complete sample) and only a small minority (12.2%) chose crowdfunding. One might think that this is due to the amount to be invested, which seems relatively high for crowdfunding purposes, but the relation between the choice and the amount (€5000 or €10,000) is not significant. Among those who ever participated in crowdfunding, many more chose the crowdfunding option than among those who never invested in crowdfunding: 28.3% versus 10.5%. This shows that stated preferences are correlated with revealed preferences in a plausible way.

More detailed information is provided by Q4. The average percentage invested in crowdfunding is 26.2%, but there is large variation (the standard deviation is 29.3%). Many individuals choose to invest a share of 0% in crowdfunding: 62.6%. A small minority (5.4%) would invest their complete hypothetical inheritance in crowdfunding.

As expected, the average percentage is higher among actual crowdfunding participants (40.2) than among non-participants (24.3). The average fraction is also higher among those who chose crowdfunding in Q3 (61.7%) than among those who chose the traditional mutual fund or the SR-fund. Interestingly, the average share invested in crowdfunding is much higher among those who chose the SR-fund than among those who chose the traditional stock mutual fund in Q3 (38.3% and 12.8%). Like the revealed preferences, this again suggests some positive relation between preferences for SR-investments and crowdfunding.

Figure 1 presents the complete distribution of the reported shares invested in crowdfunding in Q4. It shows that answers are mainly concentrated at multiples of 10, with peaks at 0, 20, 50 and 100. While the peaks at 0 and 100 may reflect genuine choices, the peak at 50 in particular might be an expression of a lack of knowledge or skills to make a well-motivated choice. We will consider the sensitivity of our estimates for excluding these observations or treating the answers as multiple categories.

3.3 Explanatory Variables

According to the existing literature (e.g., Nagy & Obenberger, 1994), demographic factors are significant predictors of financial decisions like donations and crowdfunding investments. We include gender, age, partnership status, presence of children, education, income, and financial wealth. Following the literature on agglomeration and knowledge spillover effects (Henderson, 2007; Porter, 1996), living in an urbanized area increases the chances of involving in some non-traditional form of investments. We therefore also include a dummy for living in a city.

We include measures for risk aversion based upon a set of six subjective questions in the DNB Household Survey. All these questions are on a scale from 1 (disagree) to 7 (agree). An example is “I want to be certain that my investments are safe.” Our risk aversion index adds up risk aversion measures and subtracts indexes of risk seeking behavior. Similarly, we construct a measure for future orientation from 12 questions related to focusing on the present ot the future with answers on a seven-point scale. Both of these measures are rescaled from 0 (not risk averse at all, not future oriented at all) to 1 (extremely risk averse, extremely future oriented). Following Rossi et al. (2019), we use subjective financial literacy, based upon the question how much respondents think they know about financial matters, on a scale from 1 (least knowledgeable) to 4 (most knowledgeable).

To account for the randomizations in the SP questions, the models for the SP questions include dummies for the amount of the hypothetical inheritance (€5000 or €10,000, Q3 and Q4) and the annual return differential on the SR-investment (0.5% or 1%; Q3 only).

Finally, to investigate the relation between crowdfunding and SRI, we use information on whether respondents or their households actually invest in SR-assets, one of the variables extensively analyzed by Rossi et al. (2019). Details of variable definitions and summary statistics are presented in Table 5 in the appendix. In Sect. 4.4, we will also use information on reasons for investing in SR-assets or not. These variables will be explained in Sect. 4.4.

4 Results

4.1 Actual Participation in Crowdfunding and SR-Investments

Table 1 presents the results of several probit models. In the first column, the dependent variable indicates whether the respondent has ever heard of crowdfunding. Column 2 is a probit model for actual participation in crowdfunding for the subsample of those who have heard of crowdfunding. In order to analyze the relation with investing in SR-assets, the final two columns present the results of a bivariate probit model explaining investing in SR-assets as well as participation in crowdfunding for the complete sample (where those who have never heard of crowdfunding automatically are non-participants).

Keeping other variables constant, women are less likely to have heard about crowdfunding than men are. The difference is about 3.8%-points, on average. The probability that someone has heard of crowdfunding is hump shaped in age, with a maximum at age 48. There is a strong educational gradient as well as a significant positive association with self-assessed financial literacy. There is also a positive association with financial wealth and with future orientation. Income, risk aversion and urbanization are not significant.

Column 2 explains participation in crowdfunding given knowledge of crowdfunding. Although the two age variables are not individually significant, they are jointly significant, implying that participation falls with age after age 28 (holding everything else constant). This is in line with the results obtained by Mollick (2014), who argues that older investors are reluctant if it comes to non-traditional forms of investment. Income and wealth are not significant, in line with evidence of Brent and Lorah (2019) who found that income does not affect the ability to raise capital in the case of civic crowdfunding platforms.

On the other hand, in line with findings of Nagy and Obenberger (1994), education has a strong positive impact, giving those with university education a more than 8%-points higher probability of participation in crowdfunding than low educated respondents, ceteris paribus. The effect of living in an urbanized area is also significant, though much smaller in magnitude than the education effects. We find a significantly positive relation with future orientation, as we would expect since many crowdfunding projects invest in sustainable projects. The relation with risk aversion is negative, but only marginally significant. The latter seems somewhat surprising since participation in crowdfunding can be quite risky (cf. Sect. 2).

In column 3, we again explain participation in crowdfunding, but now including the non-participants who never heard of crowdfunding. This changes the magnitudes of the coefficients but not their sign or significance level. The chances of participating now decrease after age 35 instead of 28. Education, urbanization and future orientation are the most important determining factors, as in column 2.

The equation is jointly estimated with a probit equation for ownership of SR-assets. Some factors have remarkably similar effects on crowdfunding and SR-participation: education level and future orientation are strongly positive for both. Nevertheless, urbanization does not matter much for SR-asset ownership. On the other hand, the effect of risk aversion is much more negative (and significant) for ownership of SR-assets than for crowdfunding. It suggests that participation in crowdfunding is not so much based upon the traditional risk and return trade-off. This may also be related to the fact that amounts invested in crowdfunding are typically rather low.

The estimated correlation coefficient between the error terms in the probit equations for participation in crowdfunding and ownership of SR-assets is 0.216 and it is significantly positive. This implies that not only observed characteristics like education and future orientation explain the positive association between participation in crowdfunding and in SR-investments in the data—there are also unobserved factors that affect the two in a similar way. This may reflect, for example, an unobserved preference for non-traditional investments.

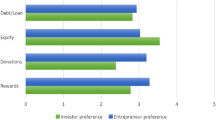

4.2 Multinomial Logit Model for Stated Choice

A multinomial logit model is implemented to analyze the stated choice question Q3, where respondents are asked to choose among three alternatives: (1) a mutual fund following the Amsterdam stock market index (AEX), (2) a crowdfunding project with fairly risky return, or (3) an investment fund investing in selected socially responsible firms. The traditional investment in the AEX mutual fund is taken as the benchmark, so that the parameters should be interpreted in terms of log odds rations of choosing crowdfunding (col. 2) or SR-assets (col. 3) instead of the AEX mutual fund.

First of all, higher educated people much more often choose crowdfunding as well as SR-assets. The first result is in line with the revealed preference results in Table 1. The strong positive effect of education on SR-assets was also found by Rossi et al. (2019). Financial literacy is negatively associated with choosing SR-assets but does not significantly change the tendency to invest in crowdfunding instead of the AEX. Like in Table 1, a preference for crowdfunding is positively associated with living in an urban area, confirming the results of Carè et al. (2018) who claim that modern cities have a crucial role as drivers of entrepreneurship and innovation.

Choosing the crowdfunding option is negatively related to the respondent’s income. This is different from what we found in Table 1. Possibly, lower income groups have a stronger preference for crowdfunding than high-income groups, but their savings are too low to actually invest in crowdfunding. Having children diminishes the chances to choose crowdfunding or SR-assets instead of the traditional AEX fund, but the effect is only marginally significant.

Risk aversion and time preference are insignificant for both types of assets. While risk aversion and future orientation are certainly important for real portfolio choices (cf. Table 1), it seems plausible that they are not important in the SP experiment, since there is no obvious difference among the long-term nature or the risks involved with the three investments.

Finally, the two randomizations in the SP question do not play an important role. We find that a larger amount to be invested somewhat reduces the chances of choosing crowdfunding, as we might expect, since amounts invested in crowdfunding are typically quite small, but the difference is not significant. The interest rate differential between the AEX fund and the SR-fund was expected to have a negative effect on the chances of choosing the SR-fund, but the point estimate is positive and insignificant. The insignificant effect on choosing crowdfunding rather than the AEX-fund was to be expected, since the trade-off between crowdfunding and the AEX-fund is not affected by the characteristics of the SR-fund.

4.3 Tobit Model for Share Invested in Crowdfunding

Table 3 presents the results for several specifications of a two-limit tobit model explaining the chosen share invested in crowdfunding (in %) reported in Q4, accounting for censoring at the lower bound 0 as well as the upper bound 100.Footnote 3 We first discuss the benchmark specification in column 1, with the other columns referring to several alternative specifications and robustness checks (explained below).

Women have a higher probability of investing a larger share of the hypothetical inheritance in a crowdfunding project, ceteris paribus. This is line with the results of Rossi et at. (2019) who found that women tend to allocate more to the socially responsible investment fund than males do. We did not find this when considering the extensive margin only, either for revealed (Table 1) or stated (Table 2) crowdfunding choices.

In line with Tables 1 and 2, age is not significant.Footnote 4 The educational dummies are jointly significant at the 10 percent level only and suggest that individuals with higher vocational training tend to invest most in crowdfunding, ceteris paribus. Overall, the role of education level is much smaller than for stated and revealed preferences in SR-assets, where the strong positive association with education is much more salient (cf. Rossi et al., 2019). Financial literacy on the other hand has a strong negative association with the share invested in crowdfunding, similar to what Rossi et al. (2019) found for the stated preference for SR-investments.Footnote 5 Apparently, the more literate respondents go for the traditional investment, possibly because they think it gives a better risk return trade off. Note that financial literacy did not play a role for crowdfunding choices in Tables 1 and 2, so it seems something that matters at the intensive rather than at the extensive margin.

Living in an urbanized area has a significant positive effect on actual and stated participation in crowdfunding at the extensive margin in Tables 1 and 2, but the effect is not significant (though still positive) in Table 3, suggesting that the urban networks argument of Carè et al. (2018) mainly matters at the extensive margin.

Income, wealth and the presence of children are insignificant. Having a partner has a strong and significant negative effect, however. It reduces the expect share by approximately 2.9 percentage points, on average. Again, the result here is different from that in Table 2, where children had a significant negative effect while partnership status was not significant. This confirms that crowdfunding choices at the intensive and extensive margin are different.

Risk aversion has an insignificant negative effect, like in Table 2. Similarly, there is no evidence that future orientation plays a role. As expected, the amount of the hypothetical inheritance has a negative association with the share invested in crowdfunding, but the effect is insignificant (cf. Sects. 4.1 and 4.2).

A well-known result in personal finance is the “1/N rule” of naïve diversification (Benartzi & Thaler, 2001). The use of this rule of thumb implies that individuals who do not or cannot make a rational choice often divide the total amount that is invested equally over the N available assets. In Q4, this would mean they allocate 50% to the AEX fund and 50% to crowdfunding, explaining the peak at 50% in Figure 1. Column 2 in Table 3 presents the estimates if all 347 50%-observations are discarded, assuming they are due to a different choice process. The effect is limited. Most point estimates increase in value, but significance levels remain similar to those in column 1.Footnote 6

Another robustness check is presented in column 3. Since Fig. 1 suggests that the reported shares are strongly rounded, we constructed a categorical outcome variable that is much less sensitive to rounding, with categories 0, (0,25], (25,50), (50,75], (75,100) and 100. Like in column 2, 50% answers are discarded. We then estimated an ordered probit model explaining the categorical outcome. While the size of the estimates in this column is not comparable to that in the other columns since the dependent variable has a completely different scale, the signs and significance levels are largely in accordance with the results in the other columns. The main difference seems to be that the positive effect of living in an urbanized area is now significant.

In column 4, we use all available observations including the 50% answers, but add dummy variables for actual participation in crowdfunding and actual ownership of SR-assets to the benchmark specification. Both dummies enter significantly with a positive sign. The positive association with actual crowdfunding participation confirms that stated and revealed preferences are positively associated, controlling for all the covariates. This is of course to be expected if stated preferences carry information on true investment preferences. The result is similar to what Rossi et al. (2019) found for SR-investments. The positive effect of the second dummy is probably more interesting and novel: controlling for many individual characteristics and even for actual crowdfunding participation, we still find a positive relation between actually investing in SR-assets and a preference for investing in crowdfunding in Q4. This is one way of showing that preferences for the two alternative investment strategies are positively related and this relation goes beyond the positive correlation that explained by observed individual characteristics.Footnote 7 Even though both added dummies are significant, adding them does not change much in the sign, significance level, or size of the coefficients on the other explanatory variables.

4.4 Reasons for Investing in SR-Or Not and Crowdfunding Choices

In order to better understand the common factor that drive SR-investing and a preference for crowdfunding in Q4, we use information collected in the same survey on why individuals do or do not actually invest in SR-assets. Respondents who invest in SR-could choose among the following five possible reasons for doing so; the percentage among all SR-asset owners indicating that reason is in parentheses (multiple answers were allowed):

-

Because I/we want to contribute to improving society (60.4%)

-

Because I/we have more confidence in banks and people who manage these funds than in the rest of the financial sector (37.4%)

-

Because of the (financial) returns that I/we think these investments will have (24.1%)

-

Because these funds are tax favoured (or were when I/we started) (27.8%)

-

Because I/we responded to a special offer where I/we received a gift (money or something else) if I/we opened such an account or invested in such fund (3.7%)

Similarly, non-SR-investors could choose among five possible reasons for not investing in SR:

-

I/we should do this, but I/we haven't got around to it yet (procrastination; 9.5%)

-

I/we have no money to invest or save (34.8%)

-

I/we want to be able to withdraw my/our savings immediately if necessary (liquidity; 47.4%)

-

Because of the high costs or the low (expected) returns (11.1%).

-

Because I/we only want to invest my/our money with traditional banks in funds that only look at expected return and risk (14.5%).

In Table 4, we add dummy variables for each of the reasons for (not) investing in SR-assets as explanatory variables to the benchmark Tobit model in Table 3, with separate estimations for the subsamples of SR-investors and non-SR-investors.

The first column refers to the small sample of SR-investors (150 observations). Not surprisingly given the small sample size, the effects of individual characteristics are imprecisely estimated and not always in line with those in Table 3. On the other hand, two of the dummy variables for the reasons for investing in SR-assets are significant.Footnote 8 First, respondents who invest in SR-assets since they want to contribute to improving society, have substantially higher stated shares invested in crowdfunding than other SR-investors, ceteris paribus. The difference for an average observation is 8.2 percentage points (0.32 × 25.677). This difference is plausible, since the crowdfunding project, explicitly designated in Q4 as a “social, environmentally friendly or cultural project” is another way in which individuals can contribute to improving society. Second, respondents who invest in SR-assets because they have more confidence in the organizations managing these funds than in other financial sector parties, also tend to invest more in crowdfunding than other SR-investors (the ceteris paribus difference is 5.6 percentage points for an average respondent). These respondents may want to avoid the mediation through traditional financial market parties by investing directly through crowdfunding. The other three reasons are not significant, as we could probably have expected—returns on crowdfunding are unrelated to returns on SR-investments, there are no special tax advantages and special offers play no role.

The right hand column of Table 4 concerns the much larger group of respondents whose households do not invest in SR-assets (non-SR-investors, 1567 observations). Here the individual characteristics play a similar role as for the complete sample, with females investing significantly more in crowdfunding than males, and partnered or financially literate respondents investing less. Two reasons for not investing in SR-assets are significantly associated with the stated share invested in crowdfunding.Footnote 9 First, those who indicate procrastination as a reason for not investing in SR-assets (“I have not got around to it yet”) choose larger crowdfunding shares than other non-SR-investors—the ceteris paribus difference is 5.84 percentage points for an average observation. For these respondents, stated and revealed preferences differ—they also indicate a strong preference for investing in SR-assets although they actually do not invest in them. They would want to go for alternative investment strategies but stick to the traditional default. Second, as expected, respondents who motivate not investing in SR-assets saying they only invest in traditional banks that only look at the risk return trade-off, are also not very interested in crowdfunding. On average, they would invest 3.70 percentage points less in crowdfunding than others, ceteris paribus. The other three reasons are not significant, which seems plausible given the nature of the SP question Q4: in the hypothetical scenario, the inheritance is there and has to be invested one way or another, so lack of money or a desire for liquidity play no role. Moreover, investors’ expected returns on SR-assets seem unrelated to crowdfunding choices, possibly since they are not related to expected returns on crowdfunding.

In summary, the results in Table 4 identify explanations for the common factors in decisions on crowdfunding and socially responsible investments. The first is a desire to allocate wealth and choose the household portfolio in such a way as to improve society, instead of choosing a portfolio exclusively considering financial risk and return, using the traditional finance arguments. The second is a lack of trust in traditional banks or other financial market parties compared to the trust in institutions specializing in socially responsible investment behavior or the trust in the organizations that seek crowdfunding. Finally, our results suggest that behavioral arguments, procrastination in particular, not only explains why relatively few people invest in SR-assets but may also drive participation in crowdfunding.

5 Conclusions

Using representative survey data on the Dutch population, we have analyzed households’ actual participation and stated preferences for participation in crowdfunding, with emphasis on the relation with investing in socially responsible assets. The results are helpful for the seekers of funds in their quest of targeting platform funders: The large majority of the Dutch have heard about crowdfunding, but only 9.4% actually participated in one or more crowdfunding projects. We find that these participants are higher educated and more future oriented than others, whereas there is no significant relation to risk aversion. Financial literacy is positively associated with knowing about crowdfunding, but not with actual participation. Crowdfunding can be seen as an alternative to traditional investments of financial wealth such as investments in an index fund, like investing in socially responsible assets. We find a strong positive association between participating in these two forms of investment, even when we control for household characteristics including education, income, total wealth, but also risk aversion, future orientation, or financial literacy.

A stated preference experiment is used to focus on preferences for crowdfunding versus other portfolio choices and to separate individuals’ preferences for crowdfunding from restrictions that hamper actual participation in crowdfunding projects such as lack of knowledge or lack of available funds. First, a stated choice question asks respondents to invest a hypothetical inheritance in either a traditional mutual fund, or an SR-fund, or a crowdfunding project. Second, respondents are asked to divide the inheritance in a share invested traditionally and a share invested in crowdfunding.

The stated choice preference experiment largely confirms the relations found with actual crowdfunding participation. The stated interest in crowdfunding is rather limited and much smaller than the stated interest in SR-assets. Earlier research concluded that there is a latent interest in SR-investing creating opportunities for extending the demand for SR-assets among several socio-economic groups, but we do not find the same result for crowdfunding. The stated choice experiment shows that at least at the extensive margin, revealed and stated preferences for crowdfunding are well aligned.

The experiment at the intensive margin, however, leads to some additional insights. The chosen shares for crowdfunding suggest, for example, that women have a stronger preference for crowdfunding than men do, a result that was also found for SR-investments. It confirms the conclusion of Prast et al. (2015) that women are underrepresented in the market for risky investments, with opportunities for attracting more individuals to alternative investment options. At the intensive margin, we also find the negative relation between a preference for alternative investments and financial literacy already established for SR-products. Financially literate respondents attach more value to the traditional risk-return trade-off and more often tend to think the alternative investment opportunities perform so well in this respect.

Considering both stated and revealed preferences, we find a strong positive relation between crowdfunding and socially responsible investing. Using the survey information on the reasons why individuals do or do not invest in SR-assets, we identify several common factors in crowdfunding and SR preferences that may explain this relationship. Both crowdfunding and investing in socially responsible assets are driven by a desire to contribute to improving society and a lack of confidence in traditional financial institutions. Moreover, the tendency to postpone conscious investment choices and stick to the reference point of traditional investment may hamper both participation in crowdfunding and investing in SR-funds. On the other hand, there is a substantial group of traditional investors focusing on risk-return trade-off who are neither interested in crowdfunding nor in SR-assets. There is scope for growth in the market for both types of non-traditional assets, but they largely target the same groups and our results suggest that the growth potential for SR-assets is larger than the potential for crowdfunding.

Notes

Follow-up questions show that more than 82% of crowdfunding participants invested less than €1000 and more than 90% invested less than 5% in crowdfunding. We will not use this information in the analysis.

\( y_{i}^{*} = x_{i}^{\prime } \beta + \varepsilon _{i} ;y_{i} = \max \left( {0,\min \left( {y_{i}^{*} ,100} \right)} \right);\;\varepsilon _{i} |x_{i} \sim N\left( {0,\sigma ^{2} } \right) \), where yi is the reported share invested in crowdfunding, xi are the explanatory variables, \( {y_{i}^{*}}\) is an unobserved (latent) variable, and β and σ2 are the parameters to be estimated.

The coefficients on age and age squared are also jointly insignificant.

To interpret the size of the coefficients, accounting for the censoring, marginal effects on the expected share for an average observation can be computed as 0.32 (= 1 − 0.626 − 0.054) times the coefficient. For example, an increase from the lowest financial literacy level (1) to the highest level (4) reduces the expected share by approximately 3 × 0.32 × 5.421 = 5.2 percentage points.

Marginal effects for an average observation remain largely similar to those in column 1, since the larger size of the point estimates is undone by the smaller fraction of uncensored observations in the reduced sample.

Yet another way to show this positive relationship is to estimate a bivariate two-limit tobit model, with one equation for the SP share invested in crowdfunding analyzed in Table 3 and another equation for the share invested in SR-assets in a similar SP question analyzed in Rossi et al., (2019, Table 4). The correlation between the unobservable components in the two equations is 0.42, strongly significant.

The same dummy variables remain significant if we also control for actual participation in crowdfunding.

The same dummy variables remain significant if we also control for actual participation in crowdfunding.

References

Aaker, J., & Akutsu, S. (2009). Why do people give? The role of identity in giving. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 19(3), 267–270.

Agrawal, A., Catalini, C., Goldfarb, A. (2011). The Geography of Crowdfunding (NBER working paper No. w16820), National Bureau of Economic Research.

Ahlers, G., Cumming, D., Günther, C., & Schweizer, D. (2015). Signaling in equity crowdfunding. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 39(4), 955–980.

Belleflamme, P., Lambert, T., & Schwienbacher, A. (2014). Crowdfunding: Tapping the right crowd. Journal of Business Venturing, 29(5), 585–609.

Benartzi, S., & Thaler, R. (2001). Naive diversification strategies in Defined Contribution saving plans. The American Economic Review, 91(1), 79–98.

Bollen, N. (2007). Mutual fund attributes and investor behavior. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 42(3), 683–708.

Brent, D., & Lorah, K. (2019). The economic geography of civic crowdfunding. Cities, 90, 122–130.

Bretschneider, U., & Leimeisterr, J. (2017). Not just an ego-trip: Exploring backers’ motivation for funding in incentive-based crowdfunding. Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 26, 246–260.

Carè, S., Trotta, A., Carè, R., & Rizzello, A. (2018). Crowdfunding for the development of smart cities. Business Horizons, 61(4), 501–509.

Editorial Team. (2020). Crowdfunding in the Netherlands touches €424M in 2019: All you need to know. Silicon Canals. https://siliconcanals.com/crowdfunding/crowdfunding-in-thenetherlands-touches-e424m-in-2019/.

European Commission, (2018). FinTech Action plan: For a more competitive and innovative European financial sector, https://ec.europa.eu/info/publications/180308-action-plan-fintech_en.

Dushnitsy, G., Guerini, M., Piva, E., & Rossi-Lamastra, C. (2016). Crowdfunding in Europe: Determinants of platform creation across countries. California Management Review, 58(2), 44–72.

Gerber, E., Hui, J., Kuo, P. (2012). Crowdfunding: Why people are motivated to post and fund projects on crowdfunding platforms. In: Proceedings of the International Workshop on Design, Influence, and Social Technologies: Techniques, Impacts and Ethics, Vol. 2, No. 11, p. 10). Northwestern University Evanston, IL.

Gerber, E., & Hui, J. (2013). Crowdfunding: Motivations and deterrents for participation. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction (TOCHI), 20(6), 1–32.

Henderson, J. V. (2007). Understanding knowledge spillovers. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 37(4), 497–508.

Ilzuka, M. (2014). Le crowdfunding: Les rouages du financement participatif-édition 2015. Edubanque Editions, Guyancourt.

Liu, W., & Aaker, J. (2008). The happiness of giving: The time-ask effect. Journal of Consumer Research, 35(3), 543–557.

Louisse, M. (2018). Crowdfunding, regulation and innovation: An interview with Loyens & Loeff. Retrieved December 10, 2020, from https://hollandfintech.com/2018/06/crowdfundingregulation-and-challenges-an-interview-with-loyens-loeff/.

Lukkarinen, A., Teich, J., Wallenius, H., & Wallenius, J. (2016). Success drivers of online equity crowdfunding campaigns. Decision Support Systems, 87, 26–38.

Massolution, (2015). 2015CF The Crowdfunding Industry Report, Massolution.com, https://www.smv.gob.pe/Biblioteca/temp/catalogacion/C8789.pdf.

Mollick, E. (2014). The dynamics of crowdfunding: An exploratory study. Journal of Business Venturing, 29(1), 1–16.

Nagy, R., & Obenberger, R. (1994). Factors influencing individual investor behavior. Financial Analysts Journal, 50(4), 63–68.

Porter, M. (1996). Competitive advantage, agglomeration economies, and regional policy. International Regional Science Review, 19(1–2), 85–90.

Prast, H., Rossi, M., Torricelli, C., & Sansone, D. (2015). Do women prefer pink? The effect of a gender stereotypical stock portfolio on investing decisions. Politica Economica, 31(3), 377–420.

Riedl, A., & Smeets, P. (2017). Why do investors hold socially responsible funds. Journal of Finance, 72(6), 2505–2550.

Rodriguez-Ricardo, Y., Sicilia, M., & López, M. (2018). What drives crowdfunding participation? The influence of personal and social traits. Spanish Journal of Marketing-ESIC, 22(2), 163–182.

Rossi, M., Sansone, D., van Soest, A., & Torricelli, C. (2019). Household preferences for socially responsible investments. Journal of Banking & Finance, 105, 107–120.

Ryu, S., & Kim, Y. (2016). A typology of crowdfunding sponsors: Birds of a feather flock together? Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 16, 43–54.

Signori, A.. Vismara, S. (2016), Returns on investments in equity crowdfunding. SSRN Working Paper, https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2765488.

Vismara, S. (2016). Equity retention and social network theory in equity crowdfunding. Small Business Economics, 46(4), 579–590.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Costanza Torricelli and Mariacristina Rossi for co-designing the survey and making the data available for this project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ciobotaru, LC., Kim, S. & van Soest, A. Household Preferences for Investing in Crowdfunding. De Economist 169, 499–522 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10645-021-09395-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10645-021-09395-0