Abstract

We analyze the performance effects of in-season manager changes in English Premier League football during the seasons 2000/2001–2014/2015. We find that some managerial changes are successful, while others are counterproductive. On average, performance does not improve following a managerial replacement. The successfulness of managerial turnover depends on specific highly unpredictable circumstances, as we illustrate through case-studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Football is very popular worldwide. In Europe and Latin-America, football has entertained crowds for more than one century. In other continents, interest has increased in the past decades. Top players now move to the football leagues of Australia, Japan and the United States, and, more recently, also to the league of the People’s Republic of China. Both clubs and national associations employ top-class managers from all around the globe to coach their squads. Furthermore, top clubs have an enormous global fan base.

The great interest in football is not restricted to fans seeking entertainment. Professional sports, in general, and professional football, in particular, have proven to be a fruitful soil for scientific research. Kahn (2000) and Szymanski (2003), for example, argue that professional sports offer interesting data to analyze labor market phenomena. In this respect, the high frequency of data obtained from controlled events is of particular interest. Results of football matches, for example, provide a straightforward and objective measure of performance (Ter Weel 2011). An element in football that has clear analogies both with business and economics is the ongoing debate about the effects of management on the performance of firms. Kuper and Szymanski (2010) question the influence of managers on the performance of professional football teams. In contrast, Anderson and Sally (2013) argue that this influence is non-negligible, as leadership appears to matter for history, in general, and for business, in particular. Pieper et al. (2014) argue, that football managers closely resemble managers in other branches of the economy with respect to personal characteristics, such as age and the capabilities to cope with stress, media attention and a large group of stakeholders.

Assuming that ‘management matters’, or, at least, that decision-makers, such as the supervisory board, suppose that ‘management matters’, one of the key decisions is the hiring and firing of managers (Ward et al. 2011). This holds in particular, if the decision to sack a manager is implemented prior to the expiration of her/his contract. Summary dismissals tend to be rather costly, so that one aims for improved performances in return. Both Pieper et al. (2014) and Van Ours and van Tuijl (2016) show that the decision to replace a manager is related to the difference between actual performance and expectations. Both studies use bookmaker odds to derive these expectations. The authors find an increased probability of replacement, if actual performances fall short of expectations. Thus, a sequence of (rather) bad results triggers clubs to replace the manager, hoping for better performances afterwards (Bruinshoofd and ter Weel 2003).

Much research has already been done on the effects of manager turnover in business. These studies mainly use stock prices, or data derived from financial statements that are only published with a lag, viz. on a quarterly or annual basis. These outcomes point at a statistically significant but small positive effect (Ter Weel 2011). Studies on the effectiveness of managerial changes in professional football have been done for a variety of European countries, for example, Belgium, England, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands and Spain (see for a recent overview Van Ours and van Tuijl 2016).

Two Belgian studies, Balduck et al. (2010a, (2010b), find no performance effects of a coach replacement. Studying English football, Poulsen (2000) finds no effects of a managerial change while Dobson and Goddard (2011) find a negative effect, just after the replacement of a manager. Analyzing data from German football, Salomo and Teichmann (2000) find negative effects of a trainer-coach dismissal, while Hentschel et al. (2012) conclude that a coach change may have a positive effect on homogeneous teams but no effect for heterogeneous teams. De Paola and Scoppa (2011) find similar conclusions for Italian football, just like Tena and Forrest (2007) for Spanish football. Koning (2003), Bruinshoofd and ter Weel (2003), Ter Weel (2011), Van Ours and van Tuijl (2016) study the effects of the replacement of head-coaches in the highest professional football league of the Netherlands. They all find that this does not lead to better performance of the teams involved.

We study the effects of managerial changes using data of the English Premier League. We apply the method initially used by Van Ours and van Tuijl (2016). Studying Dutch professional football, they account for potential selectivity of managerial changes by, first, correcting for the strength of the opponent and, second, by defining a counterfactual case with a similar development of performances prior to the hypothetical change, but without the managerial change actually taking place. The authors use the so-called cumulative surprise as an indicator of the difference between performance and expectations. The cumulative surprise is the sum of the differences between the actual number of points and the expected number of points, as based on bookmaker odds. Then, they use this cumulative surprise to match actual coach changes to counterfactual observations. In line with most previous studies, Van Ours and van Tuijl (2016) conclude that the development of performances around the time of the change in trainer-coach is subject to regression to the mean.

Our main finding is that, on average, an in-season replacement of the manager has no effect on in-season performances. In addition to the replication of the method of Van Ours and van Tuijl (2016) for the English Premier League, we also investigate whether there is heterogeneity in the effects and find that some changes have positive effects, while other changes are counterproductive, i.e. the effects of a managerial replacement on team performance are negative. To find out whether there is a pattern in this heterogeneity of the effects of a managerial change, we also study subsamples. These subsamples are based on the origin of the manager (British vs. non-British), his age, whether or not the manager ever played for a national team, whether the team was recently promoted to the Premier League and whether the team finished top-10 or bottom-10 in the preceding season. Our main finding, i.e. managerial replacements are ineffective, stands up to the scrutiny of these subsamples. To explore potential differences between successful and unsuccessful managerial changes we present three case-studies, from which we conclude that the efficacy of managerial turnover depends on specific highly unpredictable circumstances.

Our paper is organized as follows. In Sect. 2, we present our data and our research method. Subsequently, we discuss our results in Sect. 3. Next, we present three case-studies in Sect. 4. Finally, Sect. 5 concludes.

2 Data and Set-Up of the Analysis

We use data from English Premier League (EPL) football for 15 seasons, from 2000/2001 to 2014/2015. Every season contains 20 clubs that compete according to a double round-robin format, resulting in 380 matches per season (5700 matches in total). For every match, the date, the home team, the away team and the final score are recorded. Furthermore, the dataset contains match-specific bookmaker data concerning the final result, as well as the managers in charge of the two teams per match.Footnote 1 Thus, information on in-season changes is included.Footnote 2 In case of a managerial change, we distinguish between forced ‘sackings’ and voluntary ‘resignations’.Footnote 3 Finally, the dataset contains information on the final ranks of all clubs within the EPL in the preceding season.

In our analysis, we consider the first managerial change of a club within a particular season. Thus we ignore, for example, a caretaker who is replaced after some matches by a newly hired manager. Consequently, the sample period contains 84 in-season managerial changes. We follow Van Ours and van Tuijl (2016), starting with the formation of the control group. In order to be a valid counterfactual, an observation needs to fulfill the following five requirements:

-

1.

The observation concerns the same club, but stems from a different season that does not contain an in-season change in manager. This excludes two types of changes. First, we ignore changes that occurred at clubs that only played in the EPL during just one season in the sample period. Second, we do not take changes into account at clubs that changed their manager in all of their EPL-seasons in the sample period.

-

2.

The observation should exhibit a cumulative surprise that does not differ more than 0.5 from the cumulative surprise at the time of the actual managerial change. This leads to the exclusion of cases that exhibit a rather large (positive or negative) cumulative surprise at the time of the change, compared to all other observations. Applying such a maximum value potentially results in the exclusion of both rather successful cases and rather unsuccessful cases.Footnote 4

-

3.

Consistency with the actual managerial changes requires that we exclude matching with an observation prior to the fifth match and posterior to match 34.

-

4.

For observations that fulfill the first three requirements, we look for the smallest difference between the rank number of the last match of the replaced manager and the rank number of the match attached to the potential counterfactual. By doing so, we assure that matching is also based on the time during the season at which a change takes place. The closer the rank numbers of the matches, the higher the likelihood that the pattern towards the change is similar as compared to the counterfactual. Furthermore, it makes sure that the performances of the treatment group and the control group have a more or less similar period (i.e. in terms of the number of matches or observations) to develop, after the treatment has taken place.

-

5.

In case multiple observations meet all previous requirements, we take as the counterfactual observation the one with the smallest difference in cumulative surprise as compared to the actual observation.

In our sample, ten of the managerial changes occurred, either prior to the fifth match or posterior to the 34th match. These ten changes will be left out of our analysis. Thus, 74 managerial changes remain, of which 13 do not meet the criteria for matching with a valid counterfactual case to be used in the difference-in-differences approach. Our final sample thus consists of 61 managerial changes. Table 1 presents descriptive statistics of this sample. It shows, per season and in total, the number of changes to be considered in our analysis for the complete sample, dismissals only and the subsamples that are based on managerial characteristics. We define ‘British’ managers as managers from the United Kingdom and from the Republic of Ireland, thus making a sharp distinction between these two countries and the rest of the world. For age, we distinguish between managers aged over 50 and managers aged under 50 at the time of replacement. The age of 50 is the overall average and splits the sample in two more or less equal subsamples. Table 1 further shows that managerial replacements, on average, take place around the middle of the season (column W) with the cumulative surprise then being negative (column CS). Column FS shows the average cumulative surprise at the end of the season, indicating that, for some seasons we find improvements, while for others the cumulative surprise decreases. The last three columns show the average values for our counterfactual observations. By definition, the values for the rank number of the match and for cumulative surprise are rather similar for the treatment and control group. However, the improvement in cumulative surprise is larger for the control group than for the treatment group, given the values for MFS and FS. Table 5 in the Appendix presents a detailed overview including all single managerial changes.

We estimate the parameters of the following linear model using OLS:

where \(y_{ijk}\) is the performance indicator, i denotes the club, j indicates the match and k refers to the season. We use the number of points as performance indicator.Footnote 5 Note that we investigate in-season replacements and performances. Therefore, we include club-season fixed-effects \(\eta _{ik} \), which account for unobserved elements such as the quality of a team in a particular season. Home advantage is highly relevant for the performance [see for exampleVan Ours and van Tuijl (2016)]. Consequently, a dummy is included that has value one for matches played at home. Evidently, the quality of the opponent is also important. This strength is proxied by the final rank in the previous season.Footnote 6 The latter two variables are both included in the vector \(r_{ ijk}^{\prime } \), while \(\beta \) represents the vector of parameter estimates and \(\varepsilon _{ ijk} \) is the error term. The focus of our analysis is on two variables. First, \(d_{ ijk} \) is a dummy for the treatment group, with value one if a manager has been replaced and \(\delta \) measuring the effect of the managerial change on the performance. Second, \(c_{ ijk} \) is a dummy for the control group, with value one if the ‘hypothetical’ change has taken place and with \(\lambda \) measuring the counterfactual effect on the performance. An F-test for the equality of \(\delta \) and \(\lambda \) reveals whether the managerial change exerts influence on the in-season performance. First, we estimate the parameters of Eq. (1) using our complete sample. Then, we estimate the relevant parameters for dismissals only.

Figure 1 shows kernel densities for the cumulative surprises at the end of the season for the subsets of dismissals, resignations, as well as for the majority of the cases, in which no managerial change has taken place. The distribution of the cumulative surprise for the dismissals is somewhat different from the distribution of the cumulative surprise for quits. Nevertheless, they look fairly similar. However, there is a clear difference between the seasons with a managerial change compared to the seasons without a managerial change. At the end of the latter seasons there is a more positive cumulative surprise. In other words, seasons with managerial changes are seasons with worse performance than seasons without a managerial change.

3 Parameter Estimates

In analyzing the effectiveness of in-season manager replacements, we first use all 61 changes for which we have found a valid counterfactual. Then, we focus on the subset of dismissals. The parameter estimates for all managerial changes are presented in the first column of Table 2. ‘Rank Opponent’ is a measure of the strength of the opponent, while ‘Home’ represents home advantage. The variable ‘Manager change’ measures the difference in performance before and after a managerial change. Without taking a control group into account, we can interpret the coefficients of this variable as treatment effects. A significant positive value indicates that performances improved, suggesting that changes were effective. However, interpreting this result as causal would be wrong, since one does not take into account the situation in which the manager would not have been replaced. Therefore, we include a dummy variable for the control group reflecting managerial replacement that did not take place. Significant and positive values for the related parameter indicate that performances went up after the ‘counterfactual’ change, i.e. the matched observation. The F-test for equality between the two managerial-change parameter shows whether there is indeed a causal effect, i.e. if the two parameters are not significantly different from each other there is no treatment effect. Table 2 also shows the number of observations in the treatment and control groups, both separately and combined. Differences in the number of observations between the treatment and control groups arise because some club-season combinations are a control group for multiple treatment groups.

Interpreting Table 2, while focusing on the results for all changes, we observe that both the strength of the opponent as well as the home advantage are highly significant. They both have the expected sign. The weaker the opponent, the better the outcome, while home matches also result in better results. Furthermore, we find a highly significant and positive coefficient for a managerial change. Our naïve conclusion would be that a change in manager is successful on average. However, we find similar results and comparable values for the counterfactual managerial change. The F-test indeed shows that there is no significant difference between the treatment and control group. The results thus show that the improvement in performance after the change in manager (i.e. the treatment group) would also have occurred if the manager would have kept his position (i.e. the control group). On average, we do not find a causal relation between performances and the managerial changes. This finding is in line with the results of previous studies and in particular comparable to the results found by Van Ours and van Tuijl (2016).

The findings for dismissals are fairly similar. These results are presented in the second column of Table 2. Leaving out the 16 resignations, thus analyzing 45 dismissals, results in comparable values, significance and conclusions. In general, thus, we may conclude that there is no point in firing a manager after a sequence of bad results, since performances would have improved irrespective of the manager in charge.Footnote 7 Again, these results are in line with previous studies.

Table 3 shows the results for multiple subsamples which are based on the characteristics of the replaced manager.Footnote 8 In the first and second column, we distinguish between British (\(n=48\)) and non-British (\(n=13\)) coaches.Footnote 9 Column three and four contain the results for subsamples of coaches aged over 50 (\(n=29\)) and aged under 50 (\(n=32)\), at the time they were replaced. Finally, the last two columns, five and six, report the results for those coaches who were capped as an active player (\(n=30\)) and those who did not play for their country (\(n=31\)). Without going into detail, the general result is that we find significant improvements in performance after a managerial change, which is also the case for the counterfactual managerial change. However, we do not find any significant differences between treatment group and control group. This leads us to conclude that on average, for none of the subsamples, performances improve after a managerial change.

Finally, Table 4 presents the results for three subsamples that are based on the rank of the team in preceding year. The latter functions as a crude indicator of the quality and status of a club.Footnote 10 In columns one and two, we distinguish between clubs that were promoted in the previous season from the second tier of English football, the Championship, to the Premier League. Three teams were promoted in each season during the sample period, resulting in eight treatment groups to be considered, compared to 53 non-promoted teams. Extending the definition of promotion to one of the two preceding seasons, the number of treatment cases increases to 13, while 48 then belong to the non-promoted category. The results for these subsamples are presented in the third and fourth column. The last two columns provide results for subsamples where we distinguish between clubs that finished in the top half \((n=23)\) and in the bottom half \((n=38)\) of the Premier League table in the preceding season, treating promoted teams as part of the bottom. In contrast to the results in the Tables 2 and 3, we now find some insignificant values. The coefficient for the treatment group of the promoted teams in the preceding season (column 1) is positive, but insignificant, meaning that, for this subsample of cases, performances did not improve after the change in manager.

Interestingly, the coefficient for the control group is positive and significant, but the F-test for equality reveals that there is no significant difference between the treatment and control groups, which might have to do with the small number of observations in this subsample. The other insignificant results are found for the top half of the league table (column 5). Here, both coefficients for the treatment and control group are positive, but insignificant, strengthening the idea that, for this subset of club-season combinations, performances develop irrespective of the manager in charge. The F-test reveals no significant difference, which is also the case for all other subsamples that do contain positive and significant results.

4 Case Studies of Managerial Replacements

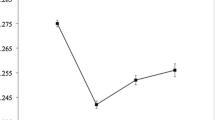

Our results in the previous section reveal that, on average, performances improve after the replacement of a manager, but the improvement is not causally related to the change. This is in line with previous studies. Nevertheless, there is a clear heterogeneity in the effects of a managerial change when we look at individual managerial changes. Figure 2 presents a scatterplot of all 61 changes included in our sample. The horizontal axis refers to the change in cumulative surprise after the managerial replacement. The vertical axis indicates the change in cumulative surprise for the control group.Footnote 11 For the sake of clarity, we added a diagonal that indicates equality of equal change in cumulative surprise for the treatment group and the control group. Observations above the line represent cases in which the control group did better than the treatment group, suggesting that the change was ineffective or even counterproductive. Observations below the line represent cases in which the managerial change was effective. Furthermore, the closer the observations are to the line, the more equal the development of the two groups is. Many observations are fairly close to the diagonal, which suggests that the managerial change was ineffective, thus supporting our average result. However, a substantial number of observations are at a fairly large distance from the diagonal, suggesting that some changes are quite effective, while others are counterproductive.

To investigate whether there are particular reasons for effectiveness or ineffectiveness of a managerial change, we selected three managerial replacements to discuss in more detail. First, we look at Chelsea FC, with treatment season 2011/2012 and counterfactual 2010/2011. This observation is indicated as a ‘diamond’ in Fig. 2. The close proximity of the ‘diamond’ towards the diagonal line suggests hardly any effect at all. Second, we discuss Leeds United FC, with treatment season 2003/2004 and counterfactual 2000/2001. This observation is indicated as a ‘triangle’ in Fig. 2. The position of the ‘triangle’ suggests a strongly negative effect. Third, we examine Newcastle United FC, with treatment season 2005/2006 and counterfactual 2012/2013. This observation is indicated as a ‘circle’ in Fig. 2. The position of the ‘circle’ suggests a substantially positive effect. All three cases concern the dismissal of the manager.

4.1 Chelsea FC

André Villas-Boas moved from FC Porto to Chelsea FC in the summer of 2011.Footnote 12 The Portuguese manager, only 33 years old at the time, had just guided the ‘Dragões’ (Dragons) to victory in the UEFA Europa League. Rumour has it that the London club paid a transfer fee of approximately 15 million euro. Villas-Boas soon presented a 3-year plan to take the London club to the top of Europe. Yet, Chelsea-owner Roman Abramovich had already run out of patience after little more than 8 months. The Russian club-owner held the manager responsible for the disappointing results. Thus, on 4 March, 2012, Chelsea FC sacked their Portuguese manager. Former Italian midfielder Roberto Di Matteo, previously an assistant to Villas-Boas, took over, initially only as a caretaker. At the end of the season, Chelsea were sixth in the table. However, Di Matteo guided them to their first ever victory in the UEFA Champions League (UCL). Moreover, Chelsea also won the FA Cup under his supervision.Footnote 13

Carlo Ancelotti became the Chelsea FC manager in the summer of 2009. The former Italian midfielder had guided AC Milan to two UCL-victories (2003, 2007). In the 2009/2010 season, he led Chelsea to the double, viz. both the EPL and the FA Cup. However, Chelsea lost both prizes in the next season. Abramovich sacked Ancelotti immediately posterior to the last match of the 2010/2011 season. One month earlier, rivals Manchester United FC had eliminated Chelsea FC in the quarter finals of the UCL, a trophy then still absent in the club’s boardroom. This has probably been a crucial element underlying this post-season sacking.

Figure 2 immediately makes clear that the difference between the control season (2010/2011) and the treatment season (2011/2012) is negligible. Moreover, the decline in cumulative surprise after the (hypothetical) change in manager is about equal for both seasons (see Fig. 3a). The efforts that resulted in winning two trophies probably explain the disappointing results in the EPL in the treatment season, despite replacing the manager, who apparently was a mismatch. After all, the importance of the FA Cup may have decreased in the twentyfirst century, but the UCL is, no doubt, the biggest prize in European club football.

4.2 Leeds United FC (LUFC)

In the 2003/2004 season, the debts of Leeds United FC were assessed as astronomically high, at around 100 million pound sterling.Footnote 14 Consequently, LUFC had to go on selling quality players, weakening their squad. The board sacked manager Peter Reid, a former England international midfielder, on 10 November 2003, a few months after his arrival at Elland Road. At that time, LUFC had gained no more than eight points from a dozen EPL matches. Eddy Gray, an all-time club-hero, took over as a caretaker. Initially, the results got better under his supervision: LUFC even moved out of the danger zone at the end of 2003. However, they subsequently lost seven matches in a row. Yet, the ‘Whites’ succeeded in bouncing back a little, one more time. However, in the end, relegation was inevitable.

David O’Leary was in charge at Elland Road from 1 October 1998, when he succeeded his former boss George Graham, until the summer of 2002. At that time, the board sacked him. O’Leary had been allowed to spend more than 100 million pound sterling in the transfer market, without winning any trophy. O’Leary’s team seriously dipped during the 2000/2001 season, but they recovered. These plunges may be ascribed to the lagged fatigue effects and leading anticipation effects of UCL matches, at least partly. In April 2001, LUFC reached the semi-finals of the UCL/European Champions’ Cup for the first time since 1975.

Figure 2 makes clear that the difference between the control season (2000/2001) and the treatment season (2003/2004) is positive. Moreover, Fig. 3b demonstrates that the cumulative surprise developed unfavourably after the managerial change in the 2003/2004 season as compared to the same period in the control season.

4.3 Newcastle United FC (NUFC)

Newcastle United FC experienced a turbulent summer in 2005.Footnote 15 Rumours concerning the club-ownership, the departure of some star-players and the failure to qualify for Europe via the UEFA Intertoto cup (UIC) all contributed to the turmoil. Meanwhile, the Scottish manager Graeme Souness, a former Liverpool FC-hero, bought some first-class players, including England striker Michael Owen, who returned to England for 17 million pound sterling, after one season at Real Madrid.

Initially, Owen nicely co-operated with Alan Shearer, the latter in his final season as an active player. However, Owen got seriously injured on New Year’s Eve. After that, the form of the team decreased severely. One month later, the NUFC board sacked Souness. A stiff battle against relegation then seemed to lie ahead for the ‘Magpies’. The 2005/2006 season then seemed to lack any prospect for the ‘Magpies’. Glenn Roeder, director of the youth academy, took over as caretaker. He guided the team from the fifteenth place to the seventh place, thus even capturing an UIC spot. The team won no less than nine matches out of the remaining 14 matches in the EPL. Irish national goalkeeper Given and Shearer uttered afterwards that Souness had never been a fans’ favourite and that his preference for certain players had been devastating for the team spirit. However, injuries had also been a crucial element in their dipping form.

In the 2012/2013 season Alan Pardew guided NUFC to the 16th place. Thus, they avoided relegation. In the FA Cup and in the Football League Cup, they only lasted one round. However, NUFC did reach the quarter finals of the UEFA Europa League, which might explain their disappointing performance in the EPL and the domestic cup competitions, at least partly.

The chemistry between Souness and part of the team had apparently gone during the treatment season (2005/2006). Moreover, the mighty fans of the ‘Magpies’ did not appreciate his work. Under such circumstances, the replacement of a manager may be an inevitable measure. During the control season (2012/2013), NUFC were mediocre in all three domestic competitions. This may be explained from huge European efforts. Thus, it is hardly surprising that the difference between the treatment season (2005/2006) and the control season (2012/2013) is positive, as Fig. 2 makes clear. Furthermore, Fig. 3c demonstrates the cumulative surprise developed favourably after the managerial change in the 2005/2006 season as compared to the same period in the control season.

5 Concluding Remarks

In English premier league football managers are replaced for various reasons, but predominantly because of poor performance (Audas et al. 1999; Dobson and Goddard 2011; Bachan et al. 2008; d’Addona and Kind 2014).Footnote 16 In our paper, we investigate the effectiveness of in-season manager replacements, using data of 15 seasons from English Premier League football. When we compare the change in performance after managerial replacements with the change in performance of counterfactual replacements we find no difference. Although we find heterogeneity in the effects of managerial changes, the successfulness seems to be related to specific and highly unpredictable circumstances. This raises the question why managers are dismissed anyway. There are several potential reasons for this. The first possible reason is that some club-owners are good in recognizing that a managerial replacement might be effective, while other club-owners are not. The second possible reason is misperception. As performance after a managerial change is often better than before, the perception is that this change was successful. True or not, club-owners are probably not interested in counterfactuals. A before–after comparison without considering a counterfactual is misleading from a researchers’ point of view, but not in the perception of club-owners, fans and mass-media. The third possible reason is asymmetry in the perception of the relationship between decision and result. Deciding for a replacement and not have an improvement in results is better than deciding not to act and not have an improvement in results. In the first case, club-owners have at least tried to improve the performance, in the second case they failed to act. The fourth possible reason is that dismissal is simply the destiny of a manager. The position of a manager has once been invented such that a manager gets the blame for disappointing results and not the club-owner (Carter 2006, 2007).

Thus, managers seem to be sacked due to reasons outside of their influence, functioning as scapegoats. In management literature this is found to be the case after bad performances (e.g. Khanna and Poulsen 1995) and might be an optimal strategy, together with the appointment of an outside successor, in the aftermath of wrongdoing (Gangloff et al. 2016). In sports, scapegoating of managers is found as well (e.g. Bruinshoofd and ter Weel 2003). Consequently, their jobs are highly uncertain. The saying “you’re only as good as your last match” seems to be typically true for professional football managers. Therefore, they will ask for some compensation in return for this uncertainty. However, many qualified managers are available, who are all willing to work in the EPL. This makes it rather easy for clubs to find a suitable replacement. Therefore, one might expect marginal demands from their side. Although CEO-compensation is based on multiple factors, such as ability (Chang et al. 2010), the opposite seems to be true, as salaries seem to be sky-high, probably including a scapegoat premium as found by Ward et al. (2011) for the CEO of listed companies as well as for college American football coaches. We have found that performances develop irrespective of the manager in charge, which is in line with the doubts of Kuper and Szymanski (2010) about the influence of football manager. Apparently, extremely high salaries reflect the compensation for job uncertainty rather than the compensation for superior quality.

Notes

The bookmaker data stem from William Hill (98 %) and from Ladbrokes (2 %), in case WH data were lacking.

The data on managers has mainly been collected from www.soccerbase.com. In case of missing or ambiguous information, we have examined newspaper archives and other internet sources.

We only consider the first managerial change of a particular club within a particular season. We have collected information on sackings and resignations from newspaper archives and BBC Sport.

Obviously, this value of 0.5 is fairly arbitrary. Yet, an extensive sensitivity analysis has made clear that different values only lead to a small change in the number of cases to be considered, without altering the main conclusions.

Alternatively, we used victory (whether a team has won the match) and goal difference as performance indicators. Then, our main findings are identical.

Promoted teams are all assigned rank 20.

It would be more accurate to formulate ‘after a sequence of results below expectations’, which emphasizes that clubs (probably) take into account the heterogeneity of opponents and the order of play in their decision to fire a manager. From Table 5 in the Appendix it becomes clear that the cumulative surprise at the moment of the managerial replacement is negative for most cases.

Note that for each group of two subsamples (i.e. British, Age and Capped) the total number of treatment groups is 61 and equal to the number for all changes in Table 2. However, the total number control groups might be different and in particular higher than the number of 45 in Table 2, since a club-season that is a counterfactual for multiple treatment groups is counted only once in Table 2, but twice if it belongs to both subsamples per group in Table 3.

As mentioned above, we define ‘British’ managers as managers from either the United Kingdom or from the Republic of Ireland.

Since the cumulative surprise at the managerial change and the cumulative surprise at the counterfactual event does not exceed 0.5, we compare the change in cumulative surprise for both events. The values are calculated from Table 5 by taking FS–CS for the treatment group and MFS–MCS for the control group.

The information in this subsection stems from the articles concerning Chelsea FC seasons in Wikipedia.

Chelsea FC sacked Roberto di Matteo on 21 November 2012, after Italian champions Juventus FC had eliminated them from the 2012/2013 UCL.

The information in this subsection stems from the articles concerning Leeds United FC seasons in Wikipedia.

The information in this subsection stems from the articles concerning Newcastle United FC seasons in Wikipedia.

See Van Ours and van Tuijl (2016) for determinants of coach replacement in other European football leagues.

References

Anderson, C., & Sally, D. (2013). The numbers game: Why everything you know about soccer is wrong. New York: Viking/Penguin.

Audas, R., Dobson, S., & Goddard, J. (1999). Organizational performance and managerial turnover. Managerial and Decision Economics, 20, 305–318.

Bachan, R., Reilly, B., & Witt, R. (2008). The hazard of being an English football league manager: Empirical estimates for three recent league seasons. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 59, 884–891.

Balduck, A., Buelens, M., & Philippaerts, R. (2010a). Short-term effects of midseason coach turnover on team performance in soccer. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 81, 379–383.

Balduck, A., Prinzie, A., & Buelens, M. (2010b). The effectiveness of coach turnover and the effect on home team advantage, team quality and team ranking. Journal of Applied Statistics, 37, 679–689.

Bruinshoofd, A., & ter Weel, B. (2003). Manager to go? Performance dips reconsidered with evidence from Dutch football. European Journal of Operational Research, 148, 233–246.

Carter, N. (2006). The football manager: A history. London: Routledge.

Carter, N. (2007). ’Managing the media’: The changing relationship between football managers and the media. Sport in History, 27, 217–240.

Chang, Y. Y., Dasgupta, S., & Hilary, G. (2010). CEO ability, pay and firm performance. Management Science, 56, 1633–1652.

d’Addona, S., & Kind, A. (2014). Forced manager turnover in English soccer leagues: A long-term perspective. Journal of Sports Economics, 15, 150–179.

De Paola, M., & Scoppa, V. (2011). The effects of managerial turnover: Evidence from coach dismissals in Italian soccer teams. Journal of Sports Economics, 13, 152–168.

Dobson, S., & Goddard, J. (2011). The economics of football (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gangloff, K. A., Connelly, B. L., & Shook C. L. (2016). Of scapegoats and signals: Investor reactions to CEO succession in the aftermath of wrongdoing. Journal of Management (forthcoming).

Hentschel, S., Muehlheusser, G., & Sliwka D. (2012). The impact of managerial change on performance. The role of team heterogeneity. CESifo working paper 3950.

Kahn, L. (2000). The sports business as a labor market laboratory. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 14, 75–94.

Khanna, N., & Poulsen, A. B. (1995). Managers of financially distressed firms: Villains or scapegoats? Journal of Finance, 50, 919–940.

Koning, R. (2003). An econometric evaluation of the effect of firing a coach on team performance. Applied Economics, 35, 555–564.

Kuper, S., & Szymanski, S. (2010). Soccernomics. London: Harper Collins.

Pieper, J., Nüesch, S., & Franck, E. (2014). How performance expectations affect managerial replacement decisions. Schmalenbach Business Review, 66, 5–23.

Poulsen, R. (2000). Should he stay or should he go? Estimating the effect of firing the manager in soccer. Chance, 13, 29–32.

Salomo, S., & Teichmann, K. (2000). The relationship of performance and managerial succession in the German Premier Football League. European Journal of Sport Management, 7, 99–119.

Szymanski, S. (2003). The assessment: The economics of sport. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 19(2003), 467–477.

Tena, J. D., & Forrest, D. (2007). Within-season dismissal of football coaches: Statistical analysis of causes and consequences. European Journal of Operational Research, 181, 362–373.

Ter Weel, B. (2011). Does manager turnover improve firm performance? Evidence from Dutch soccer. De Economist, 159, 279–303.

Van Ours, J. C., & van Tuijl, M. A. (2016). In-season head-coach dismissals and the performance of professional football teams. Economic Inquiry, 54, 591–604.

Ward, A., Amason, A. C., Lee, P. M., & Graffin, S. D. (2011). The scapegoat premium: A rational view of new CEO compensation. In M. A. Carpenter (Ed.), The handbook of research on top management teams (pp. 349–374). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Details on the Data

Appendix: Details on the Data

Table 5 provides an overview of the 61 valid matched observations. Besides information on the seasons, match rank-numbers and managers, the columns CS and MCS report the matched values of cumulative surprise which, by definition, do not differ more than 0.5. Interestingly, we do observe some (large) differences when comparing the final two columns that report the cumulative surprises at the end of the season. A difference between these two values might indicate a positive (or negative) development of performances after the replacement of the manager compared to the counterfactual. We would like to note that we compare surprises based on expectations obtained from bookmaker odds. If these odds are heavily based on recent in-season results, badly (well) performing teams are likely to face low (high) expectations, which would overestimate (underestimate) their performance in terms of surprise. Then, the cumulative surprise is probably not a good performance measure to evaluate the effectiveness of in-season coach changes, since clubs are only interested in the actual number of points obtained. We indeed use this as the main performance measure in our analyses. However, we question the focus on recent in-season performances by bookmakers, given the broad range of cumulative surprises. The cumulative surprise is a useful measure to compare performances between different clubs and seasons.

Table 5 also provides information on some characteristics of the replaced manager, i.e. his nationality (column N), in particular, whether he has a British nationality, his age (column A) at the moment of replacement and the number of caps as a player (column C). We define ‘British’ managers as managers from the United Kingdom and from the Republic of Ireland, thus making a sharp distinction between these two countries and the rest of the world. Finally, column T reports whether the change was a dismissal or a quit.

Table 6 shows the 23 managerial changes that we have excluded from the analysis.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Besters, L.M., van Ours, J.C. & van Tuijl, M.A. Effectiveness of In-Season Manager Changes in English Premier League Football. De Economist 164, 335–356 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10645-016-9277-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10645-016-9277-0