Abstract

This paper investigates the effect of a new type of financial incentive in education targeted at regional authorities. Previous studies have focused on financial incentives for students, teachers or schools. We identify the effect by exploiting the gradual introduction of a new policy aimed at reducing school dropout in the Netherlands. The introduction of the policy in 14 out of 39 regions and the use of a specific selection rule for the participating regions allow us to estimate local difference-in-differences models. Using administrative data for all Dutch students in the year before and the year after the introduction of the new policy we find no effect of the financial incentive scheme on school dropout. In addition, we find suggestive evidence for manipulation of outcomes in response to the program.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Unemployment among youths without a start-qualification is more than twice as high as unemployment among youths with a start-qualification (Statistics Netherlands 2011). In the dropout definition it makes no difference whether a dropout actually has a job or not.

Despite this minimum school-leaving age, around 2 % of the pupils aged 16 or younger turned out to leave education in the school year 2005–2006.

After the intervention year 2006–2007, compulsory education in the Netherlands was extended to youth aged between 16 and 18 without a start-qualification.

This differs from the measure of school dropout in the targets of the European Union (EU), which is the share of students aged between 18 and 24 with only lower secondary education at best and not in education or training. Hence, the most important difference compared to the EU measure is the age criterium. The required education level is well comparable in both definitions. Furthermore, the EU measure is in terms of a total stock of school dropouts rather than the number of new dropouts in a particular year.

In Dutch ‘RMC’ is an abbreviation of ‘regional report and coordination functions for early school-leaving’.

Although in most districts there were schools that also signed the covenant, the financial incentive is exclusively meant for the regional education authority. Hence, only the authority receives a payment from the government in case a reduction in school dropout is realized.

After the first year the government scaled up the program and offered new covenants to all 39 regions in late 2007 and early 2008. These new covenants are four-year instead of one-year arrangements and differ with respect to the design from 2006 covenants which we evaluate in this study.

An inherent drawback of the choice to use 2004–2005 as the reference year is that fluctuations in the dropout figures in 2005–2006 relative to 2004–2005 already affected outcomes of the covenants. We come back to this issue in Sect. 6.

The focus on preventive actions is in line with the economic literature which suggests that anti-dropout interventions targeted at students-at-risk that are still in education are much more effective than curative interventions targeted at students that already have dropped out (Heckman 2000).

We refer to Ministry of Education (2008b) for a complete list of measures in the different covenant regions.

We find similar results when using a probit model.

A similar approach is used in Leuven et al. (2007), who evaluate the effect of extra funding for disadvantaged pupils on achievement.

Other recent work on inference properties in difference-in-differences is Bertrand et al. (2004) who study implications of serial correlation.

Donald and Lang (2007) suggest estimation using group means in case of a small number of clusters and propose to use \(t\)-distributions for inference rather than the standard normal distribution.

This is because the central government yearly contributions to schools depend on the number of enrolled students to a large extent.

Within these levels we distinguish between 10 categories.

In the matched samples comparability of dropout probabilities is a consequence of the construction method.

Hence, the eligibility rule selects larger regions into treatment rather than the 12 worst-performing regions. We address potential implications of this eligibility rule on the outcomes in Sect. 6.

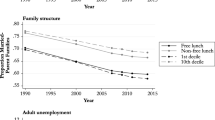

Among the pupils aged above 16, for example, average dropout percentages are 9.9 and 8.4 % in the covenant and non-covenant regions, respectively.

Since we find insignificant effects, the proposed analyses by Donald and Lang (2007) using group means do not seem necessary. For completeness, Table 14 in the “Appendix” presents the estimation results of an analysis at the school district level using group means, including 78 observations. We find statistically insignificant effects. The positive point estimates may be explained by the better performance of larger districts (see Table 7), which are less heavily weighted now.

As an alternative way to address the potential self-selection issue, we also performed analyses on a restricted estimation sample, in which the two voluntary treated districts are left out. Table 15 in the “Appendix” reports the estimated effects on the limited sample of 37 school districts. The results are very similar to our main impact findings in Table 3.

Table 16 in the “Appendix” additionallly presents the full model OLS estimates on the four subsamples for both models including fixed district effects and models including a third order polynomial of the absolute number of dropouts in the reference year. All OLS estimates are statistically insignificant. Point estimates are negative and smaller compared to the corresponding estimates on the full sample (except for the full model estimate with fixed effects in the second discontinuity sample).

As we find insignificant effects, we do not proceed with the proposed alternative analyses by Donald and Lang (2007).

Note that since eligibility was based on the absolute number of dropouts, it does not work to divide the total sample of districts in a subset of ‘larger’ and ‘smaller’ regions as almost all treatment regions would be in the former subset.

The RMC data we use concern the new dropouts, i.e. all early school-leavers within the relevant school year. Hence, the stock of previous dropouts that still satisfies the definition of a school dropout in the relevant school year is not included in both RMC and BRON data.

This region is ‘Midden-Brabant’ which reported an increase of 910 % in dropouts between 2005–2006 and 2006–2007. Inclusion of this outlier would increase average dropout development in the non-treatment regions according to RMC from 5.8 to 12.2 %.

When dividing the remaining 11 treatment regions in different subsets of high performing, middle performing and low performing regions, we observe in all of these subsets a larger reported dropout reduction in RMC compared to BRON. We do not find a clear pattern of increasing differences between RMC and BRON figures when actual performance (in terms of BRON) decreases.

References

Angrist, J., Bettinger, E., Bloom, E., King, B., & Kremer, M. (2002). Vouchers for private schooling in Colombia: Evidence from a randomized natural experiment. American Economic Review, 92(5), 1535–1558.

Angrist, J., & Lavy, V. (1999). Using Maimonides’ rule to estimate the effect of class size on scholastic achievement. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 114(2), 533–575.

Angrist, J., & Lavy, V. (2009). The effects of high stakes high school achievement awards: Evidence from a randomized trial. American Economic Review, 99(4), 1384–1414.

Bertrand, M., Duflo, E., & Mullainathan, S. (2004). How much should we trust differences-in-differences estimates. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 119, 249–275.

Burgess, S., Propper, C., Ratto, M., & Tominey, E. (2004). Incentives in the public sector: Evidence from a government agency, CMPO working paper series no. 04/103.

Dearden, L., Emmerson, C., Frayne, C., & Meghir, C. (2009). Conditional cash transfers and school dropout rates. Journal of Human Resources, 44(4), 827–857.

Dee, T. S., & Jacob, B. A. (2009). The impact of no child left behind on student achievement. NBER working paper 15531.

Deloitte Accountants. (2006). Audit over het gebruik van de informatiebronnen voortijdig schoolverlaten.

Donald, S. G., & Lang, K. (2007). Inference with difference-in-differences and other panel data. Review of Economics and Statistics, 89, 221–233.

Figlio, D., & Getzler, L. (2006). Accountabiliy, ability and disability: Gaming the system? In T. Gronberg & D. Jansen (Eds.), Advances in microeconomics, Vol. 14: Improving school accountability-checkups or choice? (pp. 35–49). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Frey, B., & Oberholzer-Gee, F. (1997). The cost of price incentives: An empirical analysis of motivation crowding-out. American Economic Review, 87, 746–755.

Fryer, R. G. (2011a). Financial incentives and student achievement: Evidence from randomized trials. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 126(4), 1755–1798.

Fryer, R. G. (2011b). Teacher incentives and student achievement: Evidence from New York City Public Schools. NBER working paper 16850.

Glewwe, P., Ilias, N., & Kremer, M. (2003). Teacher incentives. NBER working paper 9671.

Hanushek, E. A. (2006). School resources. In E. Hanushek & F. Welch (Eds.), Handbook of the economics of education, Vol. 2 (pp. 865–908). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Hanushek, E. A., & Raymond, M. E. (2005). Does school accountability lead to improved student performance? Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 24(2), 297–327.

Heckman, J. J. (2000). Policies to foster human capital. Research in Economics, 54(1), 3–56.

Holmstrom, B., & Milgrom, P. (1991). Multi-task principal-agent problems: Incentive contracts, asset ownership and job design. Journal of Law, Economics and Organization, 7, 24–52.

Jacob, B. (2005). Accountability, incentives and behavior: Evidence from school reform in Chicago. Journal of Public Economics, 89(5–6), 761–796.

Jacob, B., & Lefgren, L. (2004). Remedial education and student achievement: A regression discontinuity analysis. Review of Economics and Statistics, 86(1), 226–244.

Jacob, B., & Levitt, S. (2003). Rotten apples: An investigation of the prevalence and predictors of teacher cheating. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 3, 843–877.

van der Klauw, W. (2008). Regression-discontinuity analysis: A survey of recent developments in economics. Labour, 22(2), 219–245.

Kremer, M., Miguel, E., & Thornton, R. (2009). Incentives to learn. Review of Economics and Statistics, 91(3), 437–456.

Ladd, H. F., & Walsh, R. P. (2002). Implementing value-added measures of school effectiveness: Getting the incentives right. Economics of Education Review, 21, 1–17.

Lavy, V. (2002). Evaluating the effect of teachers’ group performance incentives on pupil achievement. Journal of Political Economy, 110(6), 1286–1317.

Lavy, V. (2009). Performance pay, teachers’ effort, productivity and grading ethics. American Economic Review, 99(5), 1979–2021.

Lazear, E. P., & Rosen, S. (1981). Rank-order tournaments as optimum labor contracts. Journal of Political Economy, 89(5), 841–864.

Lazear, E. P. (1999). Personnel economics: Past lessons and future directions. Presidential address to the Society of Labor Economists, San Francisco, May 1, 1998. Journal of Labor Economics, 17(2), 199–236.

Leuven, E., Lindahl, M., Oosterbeek, H., & Webbink, H. D. (2007). The effect of extra funding for disadvantaged pupils on achievement. Review of economics and statistics, 894, 721–736.

Maxfield, M., Schirm, A., & Rodriguez-Planas, N. (2003). The quantum opportunities program demonstration: Implementation and short-term impacts. Mathematica Policy Research Report 8279–093.

Moulton, B. R. (1986). Random group effects and the precision of regression estimates. Journal of Econometrics, 32(3), 385–397.

Ministry of Education. (2008a). Aanval op de uitval: Uitvoeren en doorzetten.

Ministry of Education. (2008b). Evaluatie convenantactie voortijdig schoolverlaten schooljaar 2006–2007, Directorate BVE.

Research voor Beleid. (2008). RMC Analyse 2007; voortijdig schoolverlaten en RMC functie 2006/2007.

Sardes. (2006). De uitkomsten van de RMC analyse 2005, Utrecht.

Springer, M. G., Ballou, D., Hamilton, L., Le, V., Lockwood, J. R., McCaffrey, D., et al. (2010). Teacher pay for performance: Experimental evidence from the project on incentives in teaching. Nashville, TN: National Center on Performance Incentives at Vanderbilt University.

Statistics Netherlands. (2011). http://www.cbs.nl/nl-NL/menu/themas/arbeid-sociale-zekerheid/publicaties/artikelen/archief/2011/2011-05-30-jeugdwerkloosheid-tk.htm.

Woessmann, L. (2003). Schooling resources, educational institutions and student performance: The international evidence. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 65(2), 117–170.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix A: Selection of Covenant Regions

see Table 9.

Appendix B: Descriptive Statistics of Subsamples

Appendix C: Additional Analyses

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

van Elk, R., van der Steeg, M. & Webbink, D. Can Financial Incentives for Regional Education Authorities Reduce School Dropout?. De Economist 161, 367–398 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10645-013-9210-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10645-013-9210-8