Abstract

A cross-sectional-based study was conducted in Torghar Pakistan to analyze the association between impacts of poor governance and household food security through sociological lens. A sample size of 379 household heads was chosen randomly for data collection through structured questionnaire. The collected data was then analyzed in terms of bivariate and multivariate analyses, and binary logit model. At bivariate analysis, the study found that inadequate governance, political instability in terms of shortage of food supply chain, smuggling of food commodities had open new vistas toward starvation and household food insecurity. At multivariate analysis, the family composition has vivid association between household food security and poor governance. Although religious education and lower level of education deteriorate the existing food security at household level were also explored. Lastly, at binary logistic regression model depicted that increased in poor governance influence household food security negatively. Thus, the government should collaborate with local political leaders to identify those lacunas and institutional weakness that affect the good governance patterns in terms of smuggling and nepotism which deteriorate the existing channel of food supply chain during militancy were put forwarded some of the recommendations in light of the present study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Since the dawn of the history, hunger and malnutrition is a tumbling issue faced by every nation across the globe (Wu et al. 2023; Hassan et al. 2020) in general while developing nation in particular due to the persistence nature of poverty and poor governance. The latter’s spectrum spans corruption, opaque accountability, arbitrary policymaking, and disillusionment (Akram et al. 2011; Nazir 2013). Diverse manifestations of this issue bear varying severity and contextual impact that motivated our research.

The current study aims to investigate the nexus between poor governance and household food security in Pakistan through quantitative approach. As per Legatum Prosperity Index (2023) reported institutional, economic, and social achievements with a focus on inclusivity and empowerment, ranks Pakistan low—136th of 167 nations among 118th on governance. These figures starkly reflect systemic failings notably in the sphere of hunger (Gupta et al. 2002). The Chinese adage “he who is hungry is never a good civil servant” underscores the nexus between governance and hunger. Effective governance is pivotal in addressing malnourishment, urging corrective actions and holistic development for sustained well-being (Kaufmann et al. 2011).

Hunger, a socially constructed phenomenon (Khan and Shah 2023), remains a pressing concern as verified by Sustainable Development Goal 2.1 (Khan et al. 2023), aiming for universal food security. The operationalized definition by the World Food Summit 1996 disclosed that food security exists when all people at all time have physical, social and economic access to safe, sufficient, and nutritious food that meet their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life (Khan et al. 2023), underpinned by four pillars: food availability, access, utilization, and stability (Adesete et al. 2022). Disconnect within these pillars breed food insecurity, exacerbating ailments like infectious diseases (Ovenell et al. 2022) and non-communicable diseases (Cox et al. 2017). Such insecurity escalates healthcare usage (Men et al. 2021) and compromises mental and physical health, particularly in vulnerable groups (Tarasuk et al. 2019).

Pakistan, a food surplus nation, grapples with high food insecurity (36.9% households), attributed largely to poor governance and institutional inadequacies (Akram et al. 2011; Nazir 2013; Hassan et al. 2020). Despite abundance, households struggle with nutritious diets due to inflation and poverty. Malnutrition rates are staggering—nearly half of children are stunted (41%), wasting rates surpass emergencies (21%), and micronutrient deficiencies are rampant (National Nutritional Survey, 2018). Concurrently, water resources strain from population growth, water-intensive farming, and mismanagement (UNICEF 2020), worsened by climate change further contributing to diseases (Khan et al. 2023). Pakistan ranks 88th in the Global Hunger Index (2020) report, with 12.3% undernourishment prevalence and an estimated 26 million people facing food insecurity (UNICEF 2020).

The main contribution of this article is threefold. First, this paper addresses gaps in the literature probing the impact of poor governance on rural household food security perceptually. Second, it employs statistical Chi-square tests to analyze the relationship between governance attributes and food security, while controlling household composition, age, and education. Finally, this study advances insights into the complex interplay of governance and food security, spotlighting crucial facets of sustainable development through application of binary logistic model.

The subsequent Sects. 2 and 3 outline prior research and the study’s methodology, respectively, while Sect. 4 presents results and discussions. The conclusion in Sect. 5 encompasses policy implications and limitations.

2 Literature review

Numerous studies have extensively explored the multifaceted issue of food insecurity (Yamano et al. 2005; Belloumi 2014; Wibe et al. 2019; Behera et al. 2023). These studies revealed that food insecurity can be chronic or transitory, both of which are sensitive to livelihood stressors (Verpoorten et al. 2013; Sargani et al. 2023) in terms of abrupt adverse shocks like job loss, climate change (Ahmad et al. 2011; Naz et al. 2020), armed conflict (George et al. 2020), insurgencies (Khan and Shah 2023), price hikes, and the COVID-19 lockdown (Arndt et al. 2020). In addition, income shocks have shown that unexpected declines drastically affect food security, with greater impact on less economically resilient households (Leete and Bania 2010).

Notwithstanding, corruption, a formidable stressor, distorts resource allocation, economic stability, and income distribution, exacerbating income inequality, and poverty (Gupta et al. 2002; Chen et al. 2023). This contributes to life dissatisfaction in corruption-laden nations (Tavits 2008). The dual negative impact of bribery, diminishing well-being for both giver and receiver as corruption consider as a hallmark of poor governance, profoundly affects food security (Sulemana et al. 2017) at macro and micro level.

Pakistan exemplifies this interplay, ranking low on corruption perceptions (Transparency International 2022). However, correlational studies establish a significant link between corruption and food insecurity (Du Perron Helal 2016). In West Africa, governance frailties related to food security mechanisms decrease food security by 20% (Anser et al. 2021). Likewise, the Cashgate scandal in Malawi caused urban poverty and food insecurity, accentuating the nexus between corruption and livelihood (Riley and Chilanga 2018).

In addition, corruption’s impact on food access is multifaceted as witnessed in Bangladesh emphasize that corruption’s financial toll forces households to reduce food consumption to accommodate bribes (Anik et al. 2013). This disproportionately affects the poor, compelling them to divert resources from food to secure essential services (Tacconi and Williams 2020). Corruption’s diversion of public investments away from essential services and food commodities resulted into starvation and food insecurity. On the other hand, corruption perpetuated lag in education and social protections measure (Du Perron Helal 2016; Mutisya et al. 2016), internal conflicts which further undermine agricultural productivity and increased unemployment at all level (George et al. 2020; Anser et al. 2021).

To sum up, the literature underscores the intricate links between governance, corruption, and food security. Adverse shocks driven by poor governance exacerbate food insecurity, perpetuating a cycle of vulnerability. These findings illuminate the urgency of addressing corruption and governance shortcomings to ensure sustainable food security and holistic development. The conceptual framework emphasizes the interconnectedness of governance, corruption, and food security, and positions them as crucial elements shaping the vulnerability of households to food insecurity. By establishing this theoretical groundwork, the study aims to empirically investigate and quantify the associations between various governance attributes and household food security, contributing to a comprehensive understanding of the complex dynamics at play.

3 Material and methods

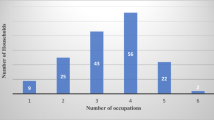

A cross-sectional and perceptional based study was conducted in District Torghar, Northern Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan, to quantitatively explore the impact of poor governance on household food security. As per Human Development Index (2017) reported that district Torghar came under the domain of “Very Low Human Development” (Khan et al. 2023). The study area had rural in nature with no urban inhabitants (Pakistan Bureau of Statistics 2017). A sample size of 379 household head was selected randomly as per Sekaran and Bougie’s criteria (2019) from the 26,464 households (Pakistan Bureau of Statistics 2017). Further the selected sample size was allocated proportionally to each stratum’s as per Bowley’s formula (1925) as highlighted in (Table 1).

3.1 Measurement of household food security

Household food security assessment commonly employs methods like the FAO approach (Smith et al. 2017), household expenditure surveys (Hoddinott and Yisehac 2002), dietary intake analysis, and anthropometry (Santoso et al. 2021). In a unique departure, this study innovatively gauges Torghar’s household food security through a perceptual assessment scale. Respondents use a Likert scale (agree, neutral, disagree) to express their perspectives by assigning numeric values, i.e., (0, 1, 2) to represent attitudes for poor governance variable while food security encompasses through agree and disagree (0 and 1), respectively (Basias and Pollalis 2018). The interview schedule was pre-tested to ensure clarity and coherence. This method introduces a fresh lens to explore food security dynamics, enriching understanding of the local context.

3.2 Indexation method and Cronbach’s alpha test

Combining attitudinal statements into indices is a standard practice in social science research, especially when assessing attitudes. Index building, merging multiple elements to measure one concept, was employed, following conventions (Nachmias and Frankfort-Nachmias 1976). Validation and internal consistency were ensured through Cronbach’s (1951) alpha test (Felder and Spurlin 2005). Likewise, a value over 0.8 as highly reliable however, a satisfactory reliability in social sciences is suggested at 0.6 as witnessed by (Nachmias and Frankfort-Nachmias 1976). Thus, food security comprised 10 attitudinal statements and poor governance had 11 items, both displaying a satisfactory reliability (Cronbach’s alpha is 0.76 and 0.73, respectively) (Fig. 1).

Pakistan: prosperity score of 2023 report Source: Legatum Prosperity Index (2023)

3.3 Data analysis

After careful investigation of data collection, the data was coded into statistical packages for social sciences (26 version) for further analysis, i.e., bivariate, multivariate analysis, and binary logistic model. First, the authors found the association through application of Chi-square tests statistics between food security (dependent variable) and poor governance attributes (independent variable). Secondly, multivariate analysis was carried out to ascertain the association between poor governance and food security while controlling three background variables namely family composition, age, and educational level (See Fig. 2). Lastly, binary logistic regression analysis was carried out to ascertain the influence of poor governance on household food security.

4 Results

4.1 Association between food security and poor governance

The analysis presented in Table 2 unveils the associations between household food security and poor governance attributes namely smuggling of food commodities (p = 0.008), political instability (p = 0.001), poor governance and corruption (p = 0.000), inflation in terms of food commodities (p = 0.000), and cost of food products import had negative effects on household budget (p = 0.000). In addition, weak official borders control management (p = 0.000), food shortage corresponding to food hoarding (p = 0.008), bad management of the pre- and post-harvest of agricultural economy (p = 0.000) and poor performance in provision of services and goods in fair and equitable manner may lead to favoritism in access to amenities of life (p = 0.000) dysfunctional household food security.

4.2 Association between poor governance and household food security

Table 3 underscores a significant association (p = 0.016) between poor governance and household food security. It could be attributed from these findings that food insecurity prevailed in the study area due to the persistence nature of poor governance as robust democratic governments, underpinned by transparent institutional functionality, can ensure food security at macro and micro level. These results were also corroborated with Ogunniyi et al. (2020) who dismantled that political stability combined with stringent anti-corruption measures and transparent law enforcement can mitigate malnutrition and hunger. Strong governance within democratic frameworks fosters economic growth, whereas poor governance breeds corruption, instability, and hindered development.

4.2.1 Association between poor governance and food security (controlling for family type of the respondents)

The association between food security and poor governance was highly significant (p = 0.000) across different family types, namely nuclear, joint, and extended family systems. It could be inferred from such findings that, a non-spurious relationship was ascertained between poor governance and food security, regardless of the family setup (Table 4).

4.2.2 Association between poor governance and food security (controlling for age of the respondents)

Upon controlling respondent age, Table 5 revealed that the association between poor governance and food security exhibited a non-significant (p = 0.069) and spurious relationship among respondents aged 46–55 years. Similarly, spurious and non-significant associations (p = 0.773, p = 0.798, p = 0.197, and p = 0.815) were observed between poor governance and food security across different age groups: 25–35, 36–45, 45–65, and above 65 years, respectively. These findings underline that individual of all age groups are susceptible to food insecurity resulting from poor governance, which should ideally ensure food provision and citizen welfare through robust institutional mechanisms.

4.2.3 Association between poor governance and food security (controlling for educational level of the respondents)

Table 6 disclosed a non-significant (p = 0.296) and non-spurious relationship between poor governance and food security for individuals with religious educational attainment. This suggests that the link between poor governance and food security does not vary significantly among respondents with religious educational backgrounds. Conversely, a significant association was evident for respondents with primary and above educational levels (p = 0.025), where non-spurious relationships between poor governance and food security prevailed. This indicates that higher educational qualifications, such as primary and beyond, enhance the perception of the detrimental effects of poor governance on food security. Such individuals may have a better understanding of governance-related issues that impact food provision. On the other hand, among illiterate respondents, a non-significant and spurious association (p = 0.450) was detected when controlling for poor governance and food security. This suggests that among illiterate individuals, the observed relationship between poor governance and food security might be influenced by confounding factors that are not directly related to education.

4.3 Binary logistic regression analysis

In the binary logistic regression model, poor governance showed a significant association (p = 0.006) to explain variations in household food security. The Omnibus test value (\(\chi \)2 = 9.235; p = 0.002) demonstrated that the test for the entire model against constant was statistically significant. Therefore, the set of predictor variables could better distinguish the variation in household food security. Further, the Nagelkerke’s R Square (R2 = 0.034) helps to interpret that the prediction variable and the group variable had a strong relationship followed by 24% to 34% variation in household food security (Cox and Snell R2 = 0.024 and Nagelkerke’s R2 = 0.034). Likewise, the significant value of Wald test results for variable confirmed that poor governance (p = 0.006) significantly predicted food security at the household level. The EXP-\(\beta \) value helped to explain and determine the extent of variations in food security under the influence of poor governance. The model explains that the negative role of poor governance increased the probability of household food security (Exp \(\beta \)=− 0.824 as shown in Table 7. Based on these findings, it is possible to conclude that poor governance in terms of institutional dysfunctional and prevalence of corruption at macro and micro level in Pakistan deteriorates the household food security situation. These results were also supported by the findings of Siddiqui (2008) and Hussain and Routray (2012) who concluded that about 1800 tons of flour that are trafficked to Afghanistan each month over the northern areas of tribal regions. Due to lack of strong law enforcement agencies at the border of Pakistan with other countries, especially Afghanistan, with tribal areas, could lead to more smuggling processes. As a result, 5% of Pakistan’s wheat, 10% of its rice, and 11% of its sugar production are smuggled to other countries via informal means without paying taxes to the relevant bodies.

5 Discussion

The research underlines the intersection of poor governance and household food security. This framework draws on extensive literature highlighting the multifaceted relationship between these factors. Poor governance, characterized by corruption, arbitrary policymaking, and institutional lag, is recognized as a formidable stressor that disrupts resource allocation, economic stability, and income distribution, further exacerbating income inequality and poverty. These results were further similar with Bakhsh et al. (2020) reported that, corruption’s adverse impact on education, social protection programs, and essential services detrimentally affects food security by reducing access to quality education and diverting resources away from food consumption. Moreover, corruption’s potential to drive internal conflicts and agricultural destruction undermines food security through increased unemployment and disrupted agricultural activities.

Likewise, the role of the state is pivotal in addressing social and economic disparities through equitable and governance across society (Obobisa et al. 2023). A dynamic state facilitates a viable country by managing the production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services (Benedek et al. 2018). However, the realization of state objectives hinges on a fair governance system free from corruption and nepotism. In this regard, resource mobilization can be achieved on equitable grounds, evaluated through political, economic, and social determinants, with a focus on food security.

With regards to poor governance and supply chain outcome underscores how illegal cross-border trade, such as smuggling, disrupts food supply chains, and leads to negative repercussions on food items. These findings were also corroborated with Lindley (2020) who disclosed that, the dire consequences of organized smuggling, particularly in areas plagued by food insecurity. Furthermore, it highlights the lack of effective state mechanisms to counter such illicit activities, reflecting systemic weaknesses. The study further explored that, a stable and secure environment is crucial for the consistent provision of basic needs, including food (Yasmeen et al. 2022). These results were also in line with FAO (2023) reported that, the absence of stability could lead to shortages of essential commodities, including food, highlighting administrative failures in controlling societal structures. This situation signifies a failure to ensure stability and suggests that dynamic policies are essential for sustained food production. Notably, India’s example illustrates how poor state institutions contribute to malnutrition and food insecurity (Reddy 2015). Moreover, food security and political stability is indispensable. A strong democratic government with transparent institutional functioning plays a pivotal role in maintaining food security through good governance (Rizov 2008; Bojnec et al. 2014). Transparent execution of laws, coupled with political stability, can overcome malnutrition and hunger. Strong democratic frameworks foster economic growth and development, while poor governance encourages corruption and instability (Ogunniyi et al. 2020). With regards to corruption and its impacts on food security, these findings reinforce the link between corruption and food insecurity, highlighting that corruption undermines social development and market dynamics, leading to unpredictability and endangering national security. Likewise, escalating food prices and irregular supply chains due to inflation disrupt the food security chain from micro to macro levels. This phenomenon disproportionately affects vulnerable populations, impacting affordability and access to food.

In addition, countries dependent on imports face challenges in maintaining a consistent supply of essential food items (Bojnec et al. 2014). Disruptions in the supply chain can lead to food shortages, malnutrition, and starvation. Smuggling and price disparities exacerbate this issue (Manning 2018). In addition, the challenges in monitoring border to prevent smuggling, impacting food security. This situation may stem from inadequate border control measures, allowing smuggling to become embedded in local culture and practices (Siddiqui 2019). Likewise, poor border control disrupts supply chains, impacting food security. These results were also similar with Manning (2018) dismantled that, smuggling activities exploit these weaknesses, resulting in distorted prices and uncertain supply. Moreover, primitive harvesting and production methods are not the primary cause of food insecurity. Instead, other factors contribute to this issue as well like food hoarding. These results were also reported by Chaudhuri et al. (2021) who stated that, insufficient management leads to low production and living standards among farming communities due to the vivid consequences of climate change, droughts, and inadequate storage contribute to reduced wheat production perpetuates food insecurity (Abid et al. 2015; Ahsan et al. 2020; Kumar et al. 2021).

At multivariate analysis, the spurious and non-significant associations between poor governance and food security across various age groups highlight the pervasive impact of this phenomenon. Regardless of age, the negative repercussions of poor governance on food security remain consistent. The findings reinforce the urgent need for effective governance mechanisms to ensure food provision and address the vulnerabilities that lead to food insecurity. In addition to age, gender roles can be important for food security and sustainable livelihood among rural farmers as witnessed by Azumah et al. (2023). Lastly, with regard to educational attainment and food security, the findings underscore the critical role of education in shaping perceptions of the association between poor governance and food security. These finding is consistent with Zhang et al. (2023) on the important role of education level of farmers in market-oriented reforms and the utilization efficiency of agricultural water resources in China. A functional state, like Pakistan, must ensure protection of its citizens’ rights, including the right to food. The detrimental impact of poor governance on families’ choices between education and nutrition exemplifies the urgent need for comprehensive reforms. Inadequate access to education, often due to poverty, may lead parents to opt for alternative avenues like Madrasas, inadvertently contributing to an uneducated and potentially radicalized youth. History’s lessons highlight the dangerous nexus between hunger and terrorism. Exploitation of hunger by religious extremists’ further fuels instability and ignorance, amplifying the risks of crises. Erhabor and Ojogho’s work (2011) reinforces these findings, as their study in Nigeria demonstrated that higher levels of education are inversely related to the probability of food insecurity. With each increase in educational level, the likelihood of food insecurity decreased significantly, emphasizing education’s protective role against food insecurity.

6 Conclusion

A cross-sectional-based study was conducted in northern Pakistan to investigate the impacts of poor governance on household food security through statistical inferences. It could be concluded from the study findings that political instability in terms of smuggling of food commodities adversely affect food supply as witnessed food security and political stability are indispensable in nature. In addition, inflation and price hike on import food commodities also dysfunctional the household budget at macro and micro level perpetuating due to the prevalence of weak official borders control management and food shortage in terms of food hoarding. Moreover, the study explored that poor harvest exacerbated by hoarding caused shortage of food led to severe crisis in terms of starvation and favoritism open new vistas toward food insecurity in the study area. Lastly, the study reveals that regardless of family type, age group, or level of educational attainment, poor governance has a significant and consistent negative impact on food security. This universal effect highlights the importance of addressing governance deficiencies across all demographic groups. These findings emphasize that food security is a collective responsibility that necessitates effective governance mechanisms.

6.1 Policy implications

The government must ensure their role by giving the fundamental right to food to each citizen through various measures taken in terms of social safety nets programs, price hike control mechanism, improving quality of education with corroboration of subsidizing the food commodities to the local inhabitants irrespective of any differences in terms of cast and creed, gender, locality and religion. In addition, strengthening governance framework in term of border control with Afghanistan in particular to mitigate the duress of smuggling of food commodities and food hoarding were the major challenges faced by the government of Pakistan since the dawn were the order of the day to ensure food supply to local inhabitants first then others. Lastly, political stability is the need of the hour for Pakistan growth with vivid educational reformation along with climate resilience and agricultural through acumen legislation and executive involvement were put forwarded some of the policy implications in light of the present study.

6.2 Future research

Still the world of hunger is not accumulated, and various factors were found in data collection which need to be explored in future research, e.g., to investigate the answer—food is a source of war or war breed hunger. Thus, mix method research with huge amount of sample size need to addressed the holistic overview of institutional lacunas (poverty, smuggling, climate change, food is weapon of war, military politics, food wastage behavior, price hike, population explosion, technological and extensions services lag by the government to capture the culprit) breeding toward food insecurity.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to repository in Higher Education Commission of Pakistan but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Abid M, Scheffran J, Schneider UA, Ashfaq M (2015) Farmers’ perceptions of and adaptation strategies to climate change and their determinants: the case of Punjab province, Pakistan. Earth Syst Dyn 6:225–243

Adesete AA, Olanubi OE, Dauda RO (2022) Climate change and food security in selected sub-Saharan African countries. Environ Develop Sustain. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-022-02681-0

Ahmad JA, Dastgir A, Haseen MS (2011) Impact of climate change on agriculture and food security in India. Int J Agric Environ Biotech 4(2):129–137

Ahsan F, Chandio AA, Fang W (2020) Climate change impacts on cereal crops production in Pakistan. Int J Clim Change Strateg Manage 12(2):257–269

Akram Z, Wajid S, Mahmood T, Sarwar S (2011) Impact of poor governance and income inequality of poverty in Pakistan. Far East J Psychol Bus 4(3):43–55

Anik AR, Manjunatha AV, Bauer S (2013) Impact of farm level corruption on the food security of households in Bangladesh. Food Secur 5:565–574

Anser MK, Osabohien R, Olonade O, Karakara AA, Olalekan IB, Ashraf J, Igbinoba A (2021) Impact of ICT adoption and governance interaction on food security in West Africa. Sustainability 13(10):5570

Azumah FD, Onzaberigu NJ, Adongo AA (2023) Gender, agriculture and sustainable livelihood among rural farmers in northern Ghana. Econ Change Restruct 56:3257–3279

Bakhsh K, Abbas K, Hassan S, Yasin MA, Ali R, Ahmad N, Chattha MWA (2020) Climate change induced human conflicts and economic costs in Pakistani Punjab. Environ Sci Pollut Res 27:24299–24311

Basias N, Pollalis Y (2018) Quantitative and qualitative research in business & technology: justifying a suitable research methodology. Rev Integr Bus Econ Res 7:91–105

Behera B, Haldar A, Sethi N (2023) Agriculture, food security, and climate change in South Asia: a new perspective on sustainable development. Environ Dev Sustain. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-023-03552-y

Belloumi M (2014) Investigating the linkage between climate variables and food security in ESA countries. Reg Environ Change 42(1):172–186

Benedek Z, Fertő I, Molnár A (2018) Off to market: but which one? Understanding the participation of small-scale farmers in short food supply chains—a Hungarian case study. Agric Hum Values 35:383–398

Bojnec Š, Fertő I, Fogarasi J (2014) Quality of institutions and the BRIC countries agro-food exports. China Agric Econ Rev 6(3):379–394. https://doi.org/10.1108/CAER-02-2013-0034

Bowley AL (1925) Measurement of the precision attained in sampling. Cambridge University Press

Chaudhuri S, Roy M, McDonald LM et al (2021) Reflections on farmers’ social networks: a means for sustainable agricultural development? Environ Dev Sustain 23:2973–3008. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-020-00762-6

Chen YH, Zhang Z, Mishra AK (2023) A flexible and efficient hybrid agricultural subsidy design for promoting food security and safety. Humanities Soc Sci Commun 10(1):1–8

Cronbach LJ (1951) Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 16(3):297–334

Erhabor POI, Ojogho O (2011) Effect of quality on the demand for rice in Nigeria. Agric J 6(5):207–212

FAO (2023) The state of food security and nutrition in the world 2022. Online at https://www.fao.org/3/cc0639en/online/cc0639en.html Access on 6/6/23

Felder RM, Spurlin J (2005) Applications, reliability and validity of the index of learning styles. Int J Eng Educ 21(1):103–112

George J, Adelaja A, Weatherspoon D (2020) Armed conflicts and food insecurity: evidence from Boko Haram’s attacks. Am J Agr Econ 102(1):114–131

Gupta S, Davoodi H, Alonso-Terme R (2002) Does corruption affect income inequality and poverty? Econ Gov 3:23–45

Hassan MS, Bukhari S, Arshed N (2020) Competitiveness, governance and globalization: What matters for poverty alleviation? Environ Dev Sustain 22:3491–3518. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-019-00355-y

Hoddinott J, Yisehac Y (2002) Dietary diversity as a food security indicator food and nutrition technical assistance project. Academy for Educational Development, Washington

Hussain A, Routray JK (2012) Status and factors of food security in Pakistan. Int J Develop Issues 11(2):164–185

Kaufmann D, Kraay A, Mastruzzi M (2011) The worldwide governance indicators: Methodology and analytical issues. Hague J Rule Law 3(2):220–246

Khan Y, Shah M (2023) Exploring household food security in the purview of military politics: an associational analysis of Torghar Hinterland Pakistan. Environ Develop Sustain 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-023-03651-w

Khan Y, Ashraf S, Shah M (2023) Determinants of food security through statistical and fuzzy mathematical synergy. Environ Develop Sustain 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-023-03231-y

Kumar P, Sahu NC, Kumar S, Ansari MA (2021) Impact of climate change on cereal production: evidence from lower-middle-income countries. Environ Sci Pollut Res. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-14373-9

Leete L, Bania N (2010) The effect of income shocks on food insufficiency. Rev Econ Househ 8:505–526

Legatum Prosperity Index (2023) Online at https://www.prosperity.com/globe/pakistan

Lindley JA (2020) Shifting the focus of food fraud: Confronting a human rights challenge to deliver food security. Perth Int Law J 5:117–123

Manning L (2018) The value of food safety culture to the hospitality industry. Worldw Hosp Tour Themes 10(3):284–296

Men F, Tarasuk V (2021) Food insecurity amid the COVID-19 pandemic: food charity, government assistance, and employment. Can Public Policy 47(2):202–230

Mutisya M, Ngware MW, Kabiru CW, Kandala NB (2016) The effect of education on household food security in two informal urban settlements in Kenya: a longitudinal analysis. Food Secur 8:743–756

Nachmias D, Frankfort-Nachmias C (1976) Research methods in the social sciences. St. Martin's Press, New York

Naz R, Shah M, Ullah A, Alam I, Khan Y (2020) An assessment of effects of climate change on human lives in context of local response to agricultural production in district Buner. Sarhad J Agric 36(1):110–119

Nazir R (2013) Governance led poverty” a case study of Pakistan. Eur J Develop Ctry Stud 15:2668–3385

Obobisa ES, Chen H, Mensah IA (2023) Transitions to sustainable development: the role of green innovation and institutional quality. Environ Dev Sustain 25:6751–6780. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-022-02328-0

Ogunniyi AI, Mavrotas G, Olagunju KO, Fadare O, Adedoyin R (2020) Governance quality, remittances and their implications for food and nutrition security in sub-Saharan Africa. World Dev 127:104752

Ovenell M, Azevedo Da Silva M, Elgar FJ (2022) Shielding children from food insecurity and its association with mental health and well-being in Canadian households. Can J Pub Health 113(2):250–259

Pakistan Bureau of Statistics (2017) Census report. Online at https://www.pbs.gov.pk/census-2017-district-wise/results/009

Du Perron Helal G (2016) Corruption and food security status: an exploratory study on perceived corruption and access to adequate food on a global scale

Reddy PP (2015) Climate resilient agriculture for ensuring food security, vol 373. Springer India, New Delhi

Riley L, Chilanga E (2018) ‘Things are not working now’: poverty, food insecurity and perceptions of corruption in urban Malawi. J Contemp Afr Stud 36(4):484–498

Rizov M (2008) Institutions, reform policies and productivity growth in agriculture: evidence from former communist countries. NJAS-Wagening J Life Sci 55(4):307–323

Santoso S, Nusraningrum D, Hadibrata B, Widyanty W, Isa S M (2021). Policy recommendation for food security in Indonesia: fish and sea cucumber protein hydrolysates innovation based. Policy 13(7):71–79

Sargani GR, Jiang Y, Chandio AA et al (2023) Impacts of livelihood assets on adaptation strategies in response to climate change: evidence from Pakistan. Environ Dev Sustain 25:6117–6140. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-022-02296-5

Sekaran U, Bougie R (2019) Research methods for business: a skill-building approach. John Wiley & Sons, New York

Siddiqui K (2019) Agriculture, WTO, trade liberalisation, and food security challenges in the developing countries. The World Financial Review March–April, pp 31–40

Smith MD, Kassa W, Winters P (2017) Assessing food insecurity in Latin America and the Caribbean using FAO’s food insecurity experience scale. Food Policy 71:48–61

Sulemana I, Iddrisu AM, Kyoore JE (2017) A micro-level study of the relationship between experienced corruption and subjective wellbeing in Africa. J Develop Stud 53(1):138–155

Tacconi L, Williams DA (2020) Corruption and anti-corruption in environmental and resource management. Annu Rev Environ Resour 45:305–329

Tarasuk V, Fafard St-Germain AA, Mitchell A (2019) Geographic and socio-demographic predictors of household food insecurity in Canada, 2011–12. BMC Pub Health 19(1):1–12

Tavits M (2008) Representation, corruption, and subjective well-being. Comp Pol Stud 41(12):1607–1630

Transparency international (2022) Online at https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2022/index/pak

UNICEF (2020) The state of food security and nutrition in the world 2020

Verpoorten M, Arora A, Stoop N, Swinnen J (2013) Self-reported food insecurity in Africa during the food price crisis. Food Policy 39:51–63

Wibe K, Robinon S, Cattaneo A (2019) Climate change, agriculture and food security: impacts and potential for adaptation and mitigation. Sustain Food Agric. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-812134-4

Wu L, Zhang L, Li Y (2023) Basis for fulfilling responsibilities, behavior, and professionalism of government agencies and effectiveness in public–public collaboration for food safety risk management. Humanities Soc Sci Commun 10(1):1–16

Yamano T, Alderman H, Christiaensen L (2005) Child growth, shocks, and food aid in rural Ethiopia. Am J Agr Econ 87(2):273–288

Yasmeen R, Padda IUH, Yao X et al (2022) Agriculture, forestry, and environmental sustainability: the role of institutions. Environ Dev Sustain 24:8722–8746. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-021-01806-1

Zhang M, Qin J, Tan H et al (2023) Education level of farmers, market-oriented reforms, and the utilization efficiency of agricultural water resources in China. Econ Change Restruct. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10644-022-09474-5

Acknowledgements

The authors thank to the study participants in data collection.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

All authors have given explicit consent to submit and publish this work.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Khan, Y., Bojnec, Š., Daraz, U. et al. Exploring the nexus between poor governance and household food security. Econ Change Restruct 57, 92 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10644-024-09679-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10644-024-09679-w