Abstract

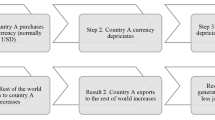

A country devalues or allows its currency to depreciate so that it can export more and increase its inpayments and import less to reduce its outpayments. Since exchange rate changes work through affecting traded goods prices and since there is evidence that prices adjust to exchange rate changes in an asymmetric manner, we conjecture that China’s inpayments from trading partners and its outpayments to trading partners also adjust asymmetrically to exchange rate changes. Since estimating asymmetric effects of exchange rate changes requires using nonlinear models, such models yield much more significant results than the traditional linear models. Indeed, this is the case in the trade between China and its 21 major trading partners.

Similar content being viewed by others

Change history

01 November 2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10644-021-09359-z

Notes

It should be noted that several studies have estimated the J-curve effect for China. The J-curve effect basically asserts that trade balance worsens in the short run but improves in the long run, after a currency depreciation. Examples include Brada et al. (1993), Zhang (1998, 1999) and Weixian (1999). Zhang (1999) also reviews China’s exchange rate policy.

Note that some have only considered the link between trade flows and the exchange rate and engaged in Granger causality, assuming the link is symmetric, e.g., Gradojevic and Neely (2008). Some others have assessed asymmetric effects of exchange rate volatility and not the exchange rate itself. Examples include Fang et al. (2009), Yuan and Yang (2016), Bahmani-Oskooee and Aftab (2017) and Bahmani-Oskooee and Nouira (2020).

Note that the estimates of these coefficients must also be negative. Note also that Bahmani-Oskooee (2020) has demonstrated that the estimates of λ0 in (3) and λ’0 in (4) are the same estimates of the coefficient attached to the lagged error-correction term in Engle and Granger (1987) settings.

Another advantage of this method is that it performs better in models that sample size is small. This is demonstrated by Panopoulou, E. and N. Pittis (2004),

Indeed, in applying the F test for cointegration Shin et al. (2014, p. 291) recommend treating the two partial sum variables as one variable so that the critical values of the F test stay at the same high level in both the linear and nonlinear models.

Note that Shin et al (2014, p. 291) recommend using the same critical values for the F but not for the t test when we move from linear to nonlinear models.

We have also tested for model misspecification using Ramsey’s RESET test. Due to lack of space we have reported the results in the notes to Table 3.

Other diagnostics are similar to those of the linear model and need no repetition.

Again, other diagnostics are similar to those of the nonlinear inpayment models and repetition is not needed. Assessing asymmetric effects of the exchange rate on other macrovariables is now becoming a common practice. For example, Koutmos and Martin (2003) test asymmetric effects of exchange rate exposure on stock returns on nine sector indexes across four major countries. Chien-Hsiu (2011) does the same in the Asian emerging stock markets and Bahmani-Oskooee and Saha (2016a, 2016b) in other stock markets.

References

Aftab M, Syed KBS, Katper NA (2017) Exchange-rate volatility and Malaysian-Thai bilateral industry trade flows. J Econ Stud 44:99–114

Baghestani H, Kherfi S (2015) An error-correction modeling of US consumer spending: are there asymmetries? J Econ Stud 42:1078–1094

Bahmani-Oskooee, M (2020), The J-curve and the effects of exchange rate changes on the trade balance, in Francisco L Rivera-Batiz, eds., of Francisco L Rivera-Batiz, ed., Encyclopedia of International Economics and Global Trade, World Scientific Publishing Co., Singapore, chapter 11, pp. 297–319

Bahmani-Oskooee M, Ratha A (2008) Exchange rate sensitivity of US bilateral trade flows. Econ Sys 32:129–141

Bahmani-Oskooee M, Saha S (2016a) Do exchange rate changes have symmetric or asymmetric effects on stock prices? Glob Finance J 31:57–72

Bahmani-Oskooee M, Saha S (2016b) Asymmetry cointegration between the value of the dollar and sectoral stock indices in the U.S. Int Rev Econ Finance 46:78–86

Bahmani-Oskooee M, Aftab M (2017) On the asymmetric effects of exchange rate volatility on trade flows: new evidence from US-Malaysia trade at industry level. Econ Model 63:86–103

Bahmani-Oskooee M, Arize A (2019) The sensitivity of US inpayments and outpayments to real exchange rate changes: asymmetric evidence from Africa. Int Econ J 33:455–472

Bahmani-Oskooee M, Nouira R (2020) On the impact of exchange rate volatility on Tunisia’s trade with 16 partners: an asymmetry analysis. Econ Change Restruct, Forthcom 53(3):357

Banerjee A, Dolado J, Mestre R (1998) Error-correction mechanism tests in a single equation framework. J Time Ser Anal 19:267–285

Bergstrand JH (1987), The US trade deficit: a perspective from selected bilateral trade models. New England Econ Rev. May–June Issue, pp. 19–31

Brada JC, Kutan A, Zhou S (1993) China’s exchange rate and the balance of trade. Econ Plann 26:229–242

Bussiere M (2013) Exchange rate pass-through to trade prices: the role of nonlinearities and asymmetries. Oxford Bull Econ Stat 75:731–758

Chien-Hsiu L (2011) Exchange rate exposure in the Asian emerging markets. J Multinatl Financ Manag 21:224–238

Cushman DO (1987) US bilateral trade balances and the dollar. Econ Lett 24:363–367

Durmaz N (2015) Industry level J-curve in Turkey. J Econ Stud 42:689–706

Halicioglu F (2008) The bilateral J-curve: Turkey versus her 13 trading partners. J Asian Econ 19(3):236–243

Engle RF, Granger CWJ (1987) Cointegration and error correction: representation, estimation, and testing. Econ 55(2):251–276

Fang W, Lai Y, Miller SM (2009) Does exchange rate risk affect exports asymmetrically? Asian evidence. J Int Money Financ 28:215–239

Gradojevic N, CJ Neely (2008) The dynamic interaction of trading flows, macroeconomic announcements and the CAD/USD exchange rate: evidence from disaggregated data. Federal Reserve Fed of St. Louise Working Paper Series, Working Paper 2008–006C http://research.stlouisfed.org/wp/2008/2008-006.pdf, pp. 1–35

Hajilee M, Niroomand F (2019) On the link between financial market inclusion and trade openness: an asymmetric analysis. Econ Anal Policy 62:373–381

Haynes SE, Hutchison MM, Mikeseli RF (1986) US-Japanese bilateral trade and the Yen-Dollar exchange rate: an empirical analysis. South Econ J 52:923–932

Kisswani KM, Nusair SA (2014) Nonlinear convergence in Asian interest and inflation rates. Econ Change Restruct 47:155–186

Koutmos G, Martin AD (2003) Asymmetric exchange rate exposure: theory and evidence. J Int Money Finance 22:365–383

Narayan PK (2005) The saving and investment nexus for China: evidence from cointegration tests. Appl Econ 37:1979–1990

Nusair SA (2016) The J-curve phenomenon in European transition economies: a nonlinear ARDL approach. Int Rev Appl Econ 31:1–27

Pesaran HM, Shin Y, Smith RJ (2001) Bounds testing approach to the analysis of level relationships. J Appl Econ 16:289–326

Panopoulou E, Pittis N (2004) A comparison of autoregressive distributed lag and dynamic ols cointegration estimators in the case of a serially correlated cointegration error. Econ J 7:585–617

Shin Y, Yu BC, Greenwood-Nimmo M (2014) Modelling asymmetric cointegration and dynamic multipliers in a nonlinear ardl framework festschrift in honor of peter schmidt: econometric methods and applications, eds. R Sickels, W Horrace, Springer. New York. 281–314

Weixian W (1999) An empirical study of the foreign trade balance in China. Appl Econ Lett 6:485–490

Yuan Z, Yang Z (2016) “Does exchange rate volatility affect China’s exports asymmetrically? Xitong Gongcheng Lilun yu Shijian/Sys Eng Theory Practice 36(2):308–318

Zhang Z (1998) Does devaluation of the Renminbi improve China’s balance of trade? Econ Int 51(3):437–445

Zhang Z (1999) China’s exchange rate reform and its impact on the balance of trade and domestic inflation. Asia Pacific J Econ Bus 3(2):4–22

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Valuable comments of two anonymous referees are greatly appreciated. Any remaining error, however, is our own.

The original version of this article was revised: the corresponding author of the article is Dr. Jia Xu. It has been corrected.

Appendices

Appendix

Variable definition and data sources

Quarterly data over the period 2000I–2018IV is used to carry out the empirical analysis. The data come from the following two sources:

A. Direction of Trade Statistics by the IMF.

B. International Financial statistics (IFS).

2.1 Variables

VXJ = China’s exports value to partner I or China’s inpayments from j. Source A.

VMJ = China’s imports value from partner j or China’s outpayments to partner j. Source A.

YCN = China’s aggregate output as measured by an index of real GDP. Source B.

YJ = Trading country j’s output as measured by an index of real GDP of country ‘j’. Source B.

REXi = The real bilateral exchange rate of the Chinese yuan against the currency of partner j. It is defined as REXj = (PCN. NEXj/ Pj) where NEXj is the nominal exchange rate defined as number of units of partner j’s currency per Chinese yuan, PCN is the price level in China (as measured by CPI) and Pj is the price level in country j (also measured by CPI). Thus, a decline in REX reflects a real depreciation of the yuan. All data come from source B.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bahmani-Oskooee, M., Xu, J. On the link between Chinese currency and its inpayments from and outpayments to trading partners: an asymmetric analysis. Econ Change Restruct 55, 335–359 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10644-020-09317-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10644-020-09317-1