Abstract

Using a multi-region, multi-sector computable general equilibrium model, this paper analyzes the effects of international emissions trading (IET) with a focus on labor market distortions. We construct four separate models with several different labor market specifications: (1) a model without labor market distortions; (2) a model with taxinteraction effects in the labor market; (3) a model with a minimum wage; and (4) a model in which a wage curve determines wages. We use these models to analyze how the effects of IET change according to model specification. The main results from the analysis are as follows. First, we found that IET generates gains for all participants in the model without labor market distortions. Second, even in the models with labor market distortions, importers of emissions permits are highly likely to benefit. Conversely, we show that the possibility of a welfare loss from IET is not as small for exporters of permits. In particular, in the minimum wage and wage curve models, we found that the exporters of emissions permits are likely to be disadvantaged. However, this also depends on the region in question. For example, China is likely to suffer under IET, whereas Russia is likely to benefit. Finally, if we implement policies to alleviate labor market distortion simultaneously with emissions regulation, all regions receive benefit from IET.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Although direct technical policies such as renewable energy subsidies and emissions standards have been preferred as climate change policies to date, the use of emissions trading has been increasing recently. While many countries are moving forward independently with their own emissions trading systems, there are ongoing discussions about how these different schemes can link together, with one proposal being the establishment of international emissions trading (hereafter, IET). IET is desirable for two main reasons (Jaffe et al. 2009; IPCC 2001). First, IET would equalize the marginal abatement cost (MAC) internationally and thereby minimize the total abatement cost worldwide. Second, all regions would be able to reduce emissions with a lower burden because regions with a high MAC would import emissions permits while those with a low MAC would export them.

However, this view is heavily premised on the notion of partial equilibrium. In other words, it only takes into account the emissions permit market. In reality, IET would extend beyond the emissions permit market to affect other markets indirectly. If this indirect impact works negatively by affecting various distortions in the economy, IET would no longer necessarily benefit all of the regions participating in the scheme. In fact, research employing general equilibrium models has already shown that IET would not necessarily benefit all participants.Footnote 1 Examples of such analysis include Ishikawa et al. (2012), Babiker et al. (2004), and Webster et al. (2010). For example, Ishikawa et al. (2012) conducted a theoretical analysis to demonstrate that if the introduction of IET causes the terms of trade to deteriorate significantly, participation in IET would actually be harmful.

Alternatively, Babiker et al. (2004) and Webster et al. (2010) focused on two types of effect: a “terms-of-trade effect” and a “tax-interaction effect in energy markets”. Using computable general equilibrium (CGE) models, these studies found that IET would not necessarily be beneficial for all regions. Together, these findings suggest that when the analysis of IET draws upon a general equilibrium model, it is not necessarily beneficial to all participants. The purpose of this paper is to focus on labor market distortions, which have not yet been addressed, and to analyze the effects of IET using a CGE model. More specifically, we clarify whether IET benefits all regions when labor market distortions are taken into account.

Many studies on climate policy have already focused on labor market distortions. In the double-dividend analysis, in particular, labor market distortions resulting from the existence of a labor tax are a key factor, and a large number of studies have already been conducted (e.g., Goulder 1995; Parry 1995; Bovenberg and Goulder 2002). However, because many of the CGE models used to analyze IET assume that the labor supply is exogenously fixed, the relationship between IET and the labor market distortions caused by a labor tax have not been analyzed.

Moreover, because almost all CGE models of climate policy analysis assume that wages flexibly adjust and the labor market always clears, very few studies have analyzed distortions in the form of wage rigidity.Footnote 2 Exceptions include Böhringer et al. (2003), Babiker and Eckaus (2007), Küster et al. (2007), and Guivarch et al. (2011). These studies reveal that the cost of climate change policy can depend strongly on labor market distortions. In fact, real-world labor markets feature many elements that bring about downward rigidity in wages, including minimum wage regulations, wage bargaining by labor unions, and efficiency wages,Footnote 3 and it is argued that these factors make wages inflexible, especially over the short term.

Unemployment, which is often generated by short-term economic fluctuations, tends to be ignored in the analysis of climate change, which mainly focuses on long-term impacts. It is true that the analysis of climate change policy must consider long-term impacts, but at the same time the short-term impacts of climate change policy are also important, particularly for policy makers who must be attentive to the well-being of the current generation. For example, according to the World Bank’s World Development Indicators, unemployment rates in 2017 were relatively low in Japan, the US and China (3–4%) but were high in EU, Latin America and Caribbean countries and Middle East and North-African countries (over 8%).Footnote 4 Unemployment is a serious economic problem in the latter countries. Thus, we attempt to analyze the impact of IET while taking into account some of the labor market distortions described.

We use multi-region, multi-sector static CGE models based on GTAP data. To shed light on the impact of labor market distortions on IET, we construct four separate models with different labor market specifications: (1) a model without labor market distortions (i.e., where the labor supply is determined exogenously and wages are flexible); (2) a model with tax-interaction effects in the labor market (i.e., where the labor supply is endogenously determined and a labor tax exists); (3) a model with a minimum wage; and (4) a model in which a wage curve determines wages. We use these models to analyze how the effects of IET change according to model specification.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 explains the model and data. Section 3 discusses the basic idea of labor market specification and IET, and Sect. 4 shows the results of the simulation. Finally, Sect. 5 provides the conclusion.

2 Model and Data

The algebraic representation of the model is provided in the supplementary material and Takeda et al. (2015). In addition, the simulation program written in GAMS is available from the authors upon request.

We construct a static CGE model with eight regions and 16 sectors, as shown in Table 1. The structure of our model is similar to the models used in Rutherford and Paltsev (2000), Paltsev (2001), Fischer and Fox (2007) and Takeda et al. (2014). Details on the model (including the algebraic representation of the model) are provided in the supplementary material. To analyze emissions regulations, we can use other types of models, such as a partial equilibrium model or a one-sector general equilibrium model. We use a general equilibrium model covering the whole nation because we want to evaluate the impacts of the nationwide emissions regulations. In addition, we use a multi-sector model instead of a one-sector model because the disaggregation of sectors is very important when analyzing CO2 regulations. CO2 emissions result from the use of multiple energies (petroleum, coal and gas) by multiple sources (production sectors and households). To measure CO2 emissions as precisely as possible, it is necessary to use a model with multiple energy goods and multiple sectors. For this reason, we use a multi-sector general equilibrium model.

We assume perfect competition in all markets, and production is subject to constant returns-to-scale technology (CES production functions). We divide the production sector into fossil fuel and non-fossil fuel sectors and assume that they have different production structures.

Fossil fuel production activities include the extraction of the following three goods: coal, crude oil, and gas. Figure 1 depicts the structure of the nested CES production function. Figure 1 shows that the production function of fossil fuel sectors is a two-stage CES function. Fossil fuel output is produced as a CES composite of natural resources and non-natural resource inputs. In turn, the non-natural resource input is a Leontief composite of capital, labor and other intermediate inputs. E_ES(j) indicates elasticity of substitution (EOS) between natural resource and non-natural resource inputs for sector j.

Non-fossil fuel production (including electricity) has the structure shown in Fig. 2 where numerical values indicate values of EOS between intermediate inputs and VA(j) indicates EOS between primary factors in sector j. The production of output here is from the Leontief aggregation of non-energy goods and an energy-primary factor composite. The energy-primary factor composite is a nested CES function of energy goods and primary factors. In addition, with respect to the petroleum and coal products sector, we assume that crude oil enters into the production function at the top-level Leontief nest because most crude oil serves as feedstock. Similarly, for the chemical products sector, we divide its energy use into feedstock requirements, which are treated as non-energy intermediate inputs, and the remainder. For this, we use the feedstock ratio data in Lee (2008).

A representative household represents the demand side of each region. The representative household’s utility has the structure depicted in Fig. 3a, although in some cases we modify this specification.Footnote 6 The utility function is a two-stage CES function of consumption goods (numerical values in the tree diagram indicate EOS values). The representative household makes decisions to maximize utility subject to budget constraints. The household’s income consists of factor income minus a tax payment (plus permit revenue). We assume that the endowments of primary factors are exogenously constant. We treat the international trade in goods in the same way as the GTAP model (Hertel 1997), and there is no international movement of primary factors. In addition, we assume that government consumption and investment are constant at the benchmark values. We assume that the level of lump-sum tax on the household is adjusted so that government consumption is constant at the benchmark value.

For the benchmark data, including CO2 emissions data, we employ the GTAP 8.1 database with 2007 as the base year. For elasticity parameters in production functions, we use the values in Fischer and Fox (2007) and the GTAP data, and for the Armington elasticity parameters, we use the GTAP values. The elasticity of substitution between resource and non-resource inputs in fossil fuel sectors (E_ES(j) in Fig. 1) is calibrated from the benchmark supply elasticity of fossil fuels, which is assumed to have a value of 2 for all fossil fuels.

3 Labor Market

Labor market distortion, typically represented by unemployment, is one of the main research themes in the field of macroeconomics and labor economics, and a wide variety of models has been established.Footnote 7 The cause and effect of distortion, of course, depend on the model, and the model selection is an important element for analysis. Although it is ideal to incorporate a variety of models that have been adopted in macroeconomics and labor economics, we base our study on relatively simple models. This is because it is not easy to introduce a complicated model into a multi-sector and multi-regional CGE model for climate change policy analysis. In addition, with the exception of only some cases, it is uncommon to consider labor market distortions when analyzing climate change policy. Hence, it is sufficiently meaningful to employ simple models in the first instance. In particular, we analyze the following four models: (1) model without labor market distortions (FLAB); (2) model with variable labor supply (VLAB); (3) minimum wage model (MWAGE); and (4) wage curve model (WCURVE). We explain these four models in the following subsections.

3.1 Model Without Labor Market Distortions (FLAB)

First, as a standard case, we consider a model without labor market distortions. In this model, labor supply is determined exogenously and wage rate changes flexibly. This type of model has frequently been used for climate policy CGE analysis; for example, the MIT EPPA model (Paltsev et al. 2005; Webster et al. 2010) and the OECD ENV-Linkages model (Chateau and Burniaux 2008; OECD 2009). In FLAB, wages always adjust so that the demand and supply of labor are equalized. Therefore, no distortion in the form of unemployment exists. In addition, due to constant employment the labor tax does not generate distortion.

Figure 4 represents a labor market in FLAB. LS is the labor supply curve and LD is a labor demand curve. As labor supply is exogenously determined, it is constructed as vertical at a value of E0. At the initial equilibrium, the wage adjusts to w0 so that the supply and demand of labor become equal. Employment is then equal to the fixed labor supply E0.

Then, suppose that emissions regulation is implemented. The labor demand curve shifts to LDR because production activities are restrained and labor demand decreases. However, employment remains at E0 because the wage rate declines to wR. This shift in the labor demand curve leads to a decrease in the labor market surplus of A + B. However, this is a primary effect (burden) of emissions regulation and is not attributable to the presence of the labor market distortion.

3.2 Model with Variable Labor Supply (VLAB)

In this model, labor supply, which is fixed in FLAB, is assumed to be variable (hereafter, this model is referred to as VLAB). In particular, labor supply varies endogenously depending on the consumption–leisure choices of the household. Therefore, we modify the utility function from Fig. 3a to 3b (LC in the figure is EOS between consumption and leisure). Note that the utility function of Fig. 3b is only used in Model VLAB. In this model, the labor tax causes distortion in the labor market.Footnote 8 For this reason, this model has been widely used for analysis of the double-dividend hypothesis.Footnote 9

3.3 Minimum Wage Model (MWAGE)

The most important cause of labor market distortion is potentially the downward rigidity of wages and unemployment. In reality, flexible wages are difficult to obtain because of the presence of factors such as wage bargaining by labor unions, long-term wage contracts, and the minimum wage system.Footnote 10 Although the causes of downward rigidity in wages and unemployment are diverse, we first consider a simple minimum wage model (hereafter, MWAGE). In this model, the real wage does not drop below a certain level and this causes unemployment.Footnote 11 This model has often been used in CGE analysis, for example, Babiker and Eckaus (2007) and Küster et al. (2007).

Figure 4 also depicts a labor market in an MWAGE. Suppose that at the initial equilibrium, the wage is w0 and employment is E0, and there is no unemployment. Assuming that the initial real wage w0 is set as the minimum wage rate, let us discuss the effects of emissions regulation. Emissions regulation will lead to a decrease in labor demand, and the labor demand curve shifts toward LDR. In FLAB, the wage adjusts to wR and the labor market clears. However, in MWAGE, the wage cannot fall below w0, and employment instead of wages decreases to ER, causing unemployment of UR. In FLAB, emissions regulation also leads to a decline in surplus. However, in the MWAGE case, this creates unemployment, and thus the decrease in surplus is greater by an amount of C + D. Therefore, the negative effect of emissions regulation becomes more significant in MWAGE. Although we assume that there is no unemployment in the initial equilibrium in the explanation above, we assume that there is initial unemployment in the simulation.

3.4 Wage Curve Model (WCURVE)

The minimum wage model is the simplest model that embodies downward rigidity in wages. However, the assumption that there is no wage fall is somewhat extreme. To address this, the wage curve model (WCURVE) takes the downward rigidity of wages into account more modestly. WCURVE assumes that there is a negative correlation between the real wage and the unemployment rate (Blanchflower and Oswald 2005). Let the nominal wage be \(w\), the consumer price level be \(p\), and the unemployment rate be \(\gamma.\)Footnote 12 Then, WCURVE assumes the following correlation between the real wage and the unemployment rate:

The rationale for WCURVE is based on the labor union and efficiency wage models (Hutton and Ruocco 1999), and this idea has been partially supported by empirical analysis (Blanchflower and Oswald 2005). In addition, the wage curve is frequently used for CGE analysis in studies such as those of Hutton and Ruocco (1999) and Rutherford et al. (2002), who have conducted analyses of tax reform, as well as Küster et al. (2007), Böhringer et al. (2003), and Guivarch et al. (2011), who have conducted analyses of climate policy. In WCURVE, Eq. (1) and two equations in (2) determine the real wage, the unemployment rate, and unemployment (\(UR\)):

where \(LS\) is the total labor supply (including unemployment) and \(LD \left( { = LS - UR} \right)\) is employment.Footnote 13

Figure 5 depicts the effect of emissions regulation in WCURVE. The labor supply and labor demand curves without emissions regulation are LS and LD and the relation between wage rate and employment derived from (1) is depicted by the upward-sloping curve WC.Footnote 14 In WCURVE, the wage curve determines the wage and it does not flexibly adjust; therefore, unemployment arises. Assuming that the initial wage rate is w0, employment will be E0 and unemployment will be U0. If the wage were flexible, it should fall to w1. However, because of the wage curve, the wage remains at a higher level of w0.

Again, suppose that emissions regulation is implemented. Because of the regulation, labor demand shifts toward LDR. In accordance with this decline in labor demand, there is pressure on the wage to fall. A fall in the wage on the wage curve indicates an increase in unemployment. Thus, unemployment increases to UR. As a result, the wage and employment become wR and ER, respectively. Consequently, emissions regulation results in a loss of C because of the increase in unemployment, as well as a loss of A + B from the shift in the labor demand curve. The wage curve model with limited adjustment of the wage has a mixture of FLAB and MWAGE models.

3.5 Labor Market Distortions and the Effects of IET

We have thus far reviewed four models that include labor market distortions and the effects of emissions regulation. In the models with labor market distortions, emissions regulation increases the distortion, and thus the costs associated with emissions regulation are greater than otherwise. There is a question concerning differences in the effect of IET between models with and without labor market distortions (the details of emissions trading scheme are explained in Sect. 4.1). Let us discuss a region that imports emissions permits under IET. With IET, production activities in an importer increase through the purchase of emissions permits. Consequently, its demand for labor also increases. Therefore, the negative effect in the labor market is restrained. In other words, in addition to the direct positive effect of IET, an importer benefits from the indirect positive effect resulting from a reduction in labor market distortion.

Conversely, because of the export of emissions permits, production activities contract in the exporter of the permits. This accelerates the decline in labor demand, which has already decreased through the emissions regulation, expanding the distortion in the labor market. Therefore, exporters suffer from an indirect negative effect.

In addition to the direct effect of IET and the effect caused by labor market distortions, IET has other indirect effects, such as terms of trade effects. Thus, in our model, the total welfare effect of IET is the sum of the following three effects: (1) the direct effect, (2) the effect caused by labor market distortions and (3) other indirect effects. As explained above, the direct effect is positive for all participants and the second effect is negative for permit exporters (and positive for permit importers). The third effect, which includes terms of trade effects, etc., is either positive or negative. The sign and the relative size of the three effects determine the total welfare effect of individual countries. IET exerts an indirect negative effect on the permit exporter. Therefore, not all regions can benefit from IET. Simulation later in the paper will verify how strongly the indirect effect works through the labor market as well as whether IET brings benefits to participants when labor market distortion is considered.

Finally, let us refer to the similarities and differences between IET and the international trade of goods. When a country participates in IET and exports emissions permits, it decreases production and thereby decreases employment. Similarly, when a country participates in international trade in goods and imports goods, it decreases domestic production of these goods and thereby decreases employment in the sectors of imported goods. The above two cases generate a similar impact, namely, a decrease in employment. However, international trade in goods is very different from IET. International trade in goods contracts employment in imported goods sectors but simultaneously expands the production and employment in exported goods sectors. Thus, the decrease in employment in import sectors is more than canceled out by the increase in export sectors. However, in the case of IET, exporting (importing) emissions permits experiences only the contraction (expansion) of production and employment, and it is not canceled out. This is the difference between international trade in goods and IET.

3.6 Labor Market Specification

VLAB requires us to specify EOS between leisure and consumption as well as to specify data for leisure. To address this, we use the technique suggested by Fischer and Fox (2007). They exogenously provide the benchmark values of the elasticity of compensation and non-compensation labor supply to calibrate EOS between leisure and consumption as well as the amount of leisure. For the elasticities of compensation and non-compensation labor supply, following Fischer and Fox (2007) we specify values of 0.1 and 0.3, respectively. We modify these values in the sensitivity analysis. In addition, we need to identify the labor tax rate. We assume labor taxes of 40% and 20% are imposed on Annex I regions and the remaining regions, respectively. These values of tax rates are exogenously fixed in all the simulations.Footnote 15 Since these values of labor tax rates are slightly ad-hoc, we vary these values in the sensitivity analysis.

To introduce WCURVE into the simulation, it is necessary to specify a wage curve equation. Following most existing studies, we adopt the following specification:

where \(\alpha > 0\) and \(\phi > 0\) are constants.Footnote 16\(\phi\) is referred to as the wage curve elasticity and we assume \(\phi = 0.1\) as in most existing studies.Footnote 17 This means that when the unemployment rate rises by 100% the real wage declines by 10%. For MWAGE and WCURVE, we need to specify the unemployment rates in the initial equilibrium. For this, we use the values in column UR of Table 1, which are taken from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators.Footnote 18

4 Simulations

4.1 Scenarios

The simulations in this study analyze the situation after all regions have introduced emissions regulation. The regulation takes a cap-and-trade form, and we assume that permit markets are perfectly competitive. In addition, we assume that the government auctions emissions permits and transfers permit revenue to the household in a lump-sum way. To ensure that the results are not excessively dependent on any specific scenario, we consider three abatement scenarios, shown in Table 2. The figures in the table denote the reduction rates in each region.Footnote 19 Regions for which no value is given have no obligation to reduce emissions. In S_ANN, only ANNEX I regions (excluding Russia) have an obligation to reduce emissions. In S_RC, we add Russia and China to the regions included in S_ANN. Finally, in S_WORLD, all regions reduce emissions.

Under each abatement scenario, we perform calculations when the reducing regions do (TR) and do not (NTR) engage in IET and compare the difference in the two sets of results. When the regions do not engage in IET, the price of emissions permits (i.e., MAC) varies from region to region. On the other hand, when the regions engage in IET, they establish a common market, and therefore a common price, for emissions permits.

Our concept of emissions trading assumes that individual firms trade emissions permits across borders, except for the initial allocation which is made through government auction. This assumption resembles the type of linkage between California, Quebec and Ontario. Trade among firms means that there is no market power in the emissions market. In addition, we assume that emissions trading covers all CO2 emissions including, for example, emissions from agricultural sectors and the household. When IET is possible, we can consider the scenario in which governments (not firms) trade emissions permits internationally.Footnote 20 Note that our simulation does not consider such a scenario and always assumes that emissions permits are traded among firms.

4.2 IET and Welfare Effects

Here, we consider the simulation results.Footnote 21 Table 3 shows the volume of permits traded, i.e., net imports of permits in millions of tons of carbon dioxide equivalents (MtCO2) and the effect on welfare (percentage change from the benchmark value) for each country under each abatement scenario. We provide the welfare effects with and without IET (TR and NTR). Welfare effects are measured as the change in utility level of the representative household.Footnote 22 We exclude regions without emissions regulations from the table because the focus of our analysis is only on IET participants. The “World” row indicates world welfare change including non-participating regions. Let us examine the results for each scenario.

Under S_ANN, only Japan, USA, EU27, and other OECD countries have emissions regulations, and in all four models Japan and EU27 are importers of permits and USA and other OECD countries are exporters. In other words, the type of model does not affect the pattern of IET. In FLAB, IET reduces the loss of welfare from emissions regulation for all participating regions. In other words, IET is a policy that benefits all participants in FLAB. This is consistent with the findings of the numerous CGE analyses that fail to account for labor market distortion that IET is desirable. However, the results from the other models are different.

In VLAB, permit importers also benefit from IET. However, the loss of welfare by the exporting regions (i.e., USA and other OECD countries) is larger with IET. Similarly, with MWAGE and WCURVE, permit exporters are disadvantaged under IET. In Sect. 3.5, we saw that when labor market distortions are considered, permit exporters suffer indirect negative effects. Our simulation results show that these negative effects are sufficiently large to outweigh the direct positive benefits.

Next, we examine scenario S_RC. Under scenario S_RC, Russia and China are included among the regulated regions, and both are exporters of permits. China, in particular, is a huge exporter. In FLAB, all participants benefit from IET, as was the case with S_ANN. Moreover, with S_RC, all participants also benefit from IET in VLAB. In MWAGE, however, China (an exporting region) is disadvantaged by IET. Similarly, with WCURVE, China suffers from IET. Although the abatement scenario has changed, the result that some exporters suffer from IET remains unchanged. Finally, with S_WORLD, Russia, China, India, and rest of the world are exporters of permits, and it is better for China and India not to engage in IET, which is essentially a similar result to S_RC.

In addition to impacts on participants, let us examine impacts on the world as a whole. Table 3 shows that welfare costs for the world shrink with IET in all models and scenarios. For example, in the MWAGE model in scenario S_WORLD, the world welfare decreases by 3.95% without IET. However, the loss becomes 1.44% with IET. Thus, the world welfare improves by 2.5% point with IET. Although under IET, several countries may lose, IET is desirable from the viewpoint of world welfare.

Let us summarize the above findings. First, regardless of the abatement scenarios, all participating regions benefit from IET (i.e., their welfare losses are smaller) in FLAB. Second, even with models that account for labor market distortions, regions that import emissions permits still benefit from IET. However, we found that IET may not be beneficial for exporting countries, although this depends on the model used. More specifically, in VLAB, the impact of IET on the welfare of exporting regions is ambiguous, whereas in MWAGE and WCURVE there is a greater likelihood of them being disadvantaged. In VLAB, exporters of permits lose from IET in S_ANN but they gain in S_RC and S_WORLD. On the other hand, in MWAGE and WCURVE, all exporters lose in S_ANN, and some exporters lose even in S_RC and S_WORLD.

The results also differ from country to country. For instance, China, an exporter of emissions permits, is often disadvantaged, while fellow exporter Russia rarely suffers. The above results tell us that when labor market distortion is considered, IET may confer disadvantages.

4.3 Impacts on Individual Regions

To analyze the effects of IET in detail, let us consider the impact on individual regions. As explained in Sect. 3.5, the total welfare effect of IET in our model is the sum of (1) the direct effect, (2) the effect caused by labor market distortions and (3) other indirect effects. This decomposition partially explains why IET has different effects for different regions. For example, even if the second effect has negative impacts on all permit exporters equally, an exporter with large positive impacts from the first and third effects is likely to gain from IET as a whole.

It is desirable to discuss the outcomes for all of the regions under each of the three abatement scenarios, but it is difficult to do so due to space limitations. Thus, we will only focus on other OECD countries and EU27 under S_ANN and on China and Russia under S_RC. Table 4 details the impacts in four regions. We begin by looking at other OECD countries under scenario S_ANN. For other OECD countries, the price of emissions permits rises significantly following the introduction of IET, resulting in other OECD countries exporting permits. In FLAB, GDP falls to enable the export of permits, and labor income therefore declines. However, because the revenue from selling the permits offsets this reduction, the rate of decline in household income is smaller with IET. It follows that the rate of decline in welfare is also less with IET.

In VLAB, there is an additional effect: namely, a fall in employment. In fact, the rate of decline in labor income under this model is even larger. With IET, the rate of decline in labor income increases, but there is also revenue from the sale of emissions permits, which is the same as under FLAB. The difference with VLAB, however, is that the decline in labor income is larger than the revenue from the sale of emissions permits, so the decrease in household income is larger with IET. This is why IET increases the rate of decrease in welfare. Moreover, under MWAGE and WCURVE, unemployment occurs, so the rate of decrease in employment increases further. With these two models, the expansion of labor market distortion by IET is more pronounced, and this causes the welfare loss with IET to increase.

Next, let us consider China under scenario S_RC. China is an exporter of permits, and the qualitative aspects of the impact on China are similar to other OECD countries under S_ANN. For China, however, IET is preferable under VLAB, just as it is with FLAB. In other words, the welfare effect under VLAB is the reverse of what it is for other OECD countries under S_ANN. Moreover, when compared with other OECD countries, there is a substantial difference in the size of effects on welfare with and without IET under MWAGE. In fact, the welfare loss in the presence of IET for China is approximately 3.5 times higher under MWAGE (for other OECD countries in S_ANN, only 1.1 times).

One of the reasons for the quantitative differences described above may be the difference in the price of emissions permits with and without IET. Because both China and other OECD countries are exporters of emissions permits, the price of permits increases with the introduction of IET. However, the nature of the increase is very different for the two regions. In other OECD countries, where the price of permits (MAC) is high to begin with, the increase in permit price is small (37.3 to 42.3US$/MtCO2 in FLAB). In China, however, where the price of permits is low, IET results in a more than six fold increase. Because of this, China exports large quantities of emissions permits (and reduces output at the same time). The above findings indicate that the quantitative effects of IET are quite dissimilar across the regions.

Next, let us consider Russia under scenario S_RC. We have already observed that the impacts of IET on China and Russia are quite different even though they are both exporters of permits. That is, China is often disadvantaged by IET, while Russia rarely suffers. The reason why Russia is likely to obtain large gains from IET is that the terms of trade (TOT) for Russia improve significantly when it participates in IET. For example, Table 4 shows that the TOT for Russia deteriorates by 2.9% without IET but improve by 0.6% with IET. This positive TOT effect generates large gains from IET for Russia and cancels out the negative impacts caused by the labor market distortions.

Finally, we examine EU27 under scenario S_ANN, which shows the impacts on permit importers. In all models, EU27 receives welfare gains from IET. In particular, in MWAGE, the welfare cost is reduced from 4.85% without IET to 3.72% with IET, corresponding to a reduction of 20%. The large welfare gains from IET are caused mainly by the decrease in the unemployment rate (from 11.4% without IET to 10.4% with IET). Although so far, we have focused on the decrease in the welfare of permit exporters, the above result shows that labor market distortions can reinforce the gains from IET for permit importers.

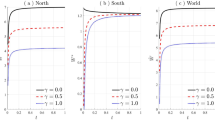

4.4 Sensitivity Analysis

In this section, we alter our assumptions concerning the models, parameters, and scenarios, and perform a sensitivity analysis to examine the extent to which this affects the results obtained so far. Scenarios of the sensitivity analysis are shown in Table 5. First, we change the reduction rates. Because there is uncertainty about the future reduction rates of many regions, we consider two scenarios: in Scenario hrd (the case of higher reduction rates), the original reduction rates in Table 2 are multiplied by 1.\(5\), and in Scenario lrd (the case of lower reduction rates), reduction rates are multiplied by 0.5.

With VLAB, the elasticity of the labor supply and the benchmark labor tax rate are important. We therefore double and halve their values (Scenarios elas_l, elas_h, ltax_l and ltax_h). On the other hand, with WCURVE, the wage curve elasticity and the benchmark unemployment rate are important, so we double and halve the values of each (Scenarios phi_l, phi_h, ur_l and ur_h).

From the preceding analysis, we confirmed that labor market distortion makes it possible for IET to confer disadvantage. This means that it should be possible, by simultaneously implementing policies to correct the distortions, to eliminate the indirect negative impact of IET and leave only the positive effects. To confirm whether this is indeed the case, we consider a situation in which policies to curtail the expansion of labor market distortion accompany the introduction of emissions regulation. More specifically, with VLAB we examine a “revenue-recycling” policy under which the revenue from the sale of emissions permits lowers the labor tax, while with MWAGE and WCURVE, we consider a policy of lowering the labor tax to maintain the benchmark level of employment.

Because of the limitation of the space, numerical results from the sensitivity analysis are omitted here.Footnote 23 We summarize the insights from sensitivity analysis. First, under FLAB, welfare improves for all participants as a result of IET in almost all scenarios of sensitivity analysis.Footnote 24 Second, under VLAB, the high values of labor supply elasticity and the labor tax rate tend to make IET disadvantageous for permit exporters. This is because high values of labor supply elasticity and the labor tax rate reinforce negative tax-interaction effects. Third, under WCRUVE, low values of wage curve elasticity and high values of the benchmark unemployment rate tend to make IET disadvantageous for permit exporters. This is because low values of wage curve elasticity reinforce the downward rigidity of wages and high values of the benchmark unemployment rate mean that the existing distortions in the labor market are large. Fourth, changes in reduction rates have ambiguous effects. In some models and abatement scenarios, an increase in reduction rates makes IET more disadvantageous, but in other models and scenarios, this is not the case.

Finally, in labor tax cut scenarios, all participants gain from IET in all models except for one case. That is, the simultaneous adoption of measures to correct distortion will always ensure that IET improves welfare, even for regions that export emissions permits. This means that by imposing emissions regulation and implementing policies to alleviate labor market distortion at the same time, we can reduce the indirect negative effects of IET, and therefore all regions can benefit from its implementation.

By changing assumptions and parameter values, the quantitative impacts of IET often change to a large extent, but almost all qualitative insights derived from the benchmark case remain unchanged. It follows that the analysis of the previous sections has a certain level of robustness.

4.5 Discussion

Our analysis has several policy implications for potential ETS linkages. The first implication is for a developed-developing country linkage. One of the potential links of this type is between EU-ETS and the Chinese ETS. Our analysis (MWAGE and WCURVE under Scenario S_RC and S_WORLD) shows that China may suffer from higher unemployment if it links its domestic ETS to EU-ETS because China will be a net exporter of emissions permits.

However, China can earn revenues from selling permits to the EU. If the Chinese government can use these revenues wisely as a measure to correct the unemployment issue, the negative impact of linking may not matter as much as initially anticipated, as shown in the sensitivity analysis. Moreover, China is one of fastest growing economies in the world. Thus, in the long run, this negative impact from linking may vanish as the Chinese economy continues to grow.

Our analysis in scenario S_ANN also has implications for a developed–developed country link. For example, one can picture the linkage between the North American markets, such as the US and Canada, and the European markets, such as the EU-ETS and Switzerland ETS. In this case, the US and Canada are expected to become exporters of permits. Developed economies tend to have higher labor tax rates, which often entail lower labor supply and larger labor market distortion. Therefore, the distortion brought by IET can have a larger negative impact. This implies that the labor distortion problem is more severe for a developed–developed country link than for a developed-developing country link, which is shown in scenario S_ANN where permit exporters always lose in models with labor market distortions.

5 Conclusion

This paper analyzes IET with a focus on labor market distortion. We develop a static CGE model with eight regions and 16 sectors and use GTAP data for the benchmark data. To analyze the relation between labor market distortion and IET, we develop four models with different labor market specifications: (1) a model with no labor market distortion, (2) a model with a labor market tax-interaction effect, (3) a minimum wage model, and (4) a wage curve model. We then compare the effects of IET using these four models.

The main results are as follows. First, we found that IET generates gains for all participants in the model without labor market distortions. This result is consistent with the results of previous studies. Second, even if there is distortion in the labor market, emissions permit-importing regions benefit from IET. On the other hand, we found that the possibility of a welfare loss from IET is not very small for emissions permit exporters. In particular, with the minimum wage model and the wage curve model, in which unemployment arises because of the downward rigidity in wage, IET is likely to generate a loss for emissions permit exporters. However, this result strongly depends on the region in question. For example, both China and Russia are exporters of permits, but the effects of IET for both are quite different in that while IET often brings about welfare losses for China, it is likely to benefit Russia. This is because the impacts of IET depend on not only the direct effects and the labor market effects but also on other effects such as the terms of trade effect. Finally, we show that IET is likely to be beneficial for all participants when policies to remedy labor market distortions are implemented alongside emissions regulation.

It is not a new finding that opening up the trade in the presence of labor market distortion may reduce welfare. In the literature of international trade theory, many studies analyzed the welfare impacts of opening up the trade where distortions exist in the labor market, for example, Brecher (1974), Corden (1984), and Helpman and Itskhoki (2010). Some of them showed that opening up the trade of goods in the presence of labor market distortions may reduce welfare. As explained in Sect. 3.5, trade in goods and trade in emissions permits are not the same, but our analysis presents an additional example of welfare-decreasing international trade.

Our analysis showed that IET can be welfare-decreasing for participants. However, if it is indeed welfare-decreasing, the question of whether governments will or will not participate in IET arises. We have two answers to this question. First, as many studies that consider political economy aspects of government behaviors show, governments do not necessarily behave to maximize social welfare. Thus, the possibility that a welfare-decreasing policy will be adopted is not small.

Second, although governments, particularly politicians, often have a strong interest in the issue of unemployment, this issue is not sufficiently considered in economic analysis. Governments usually have a strong interest in unemployment and thus will not promote IET if it is likely to increase unemployment. However, environmental economists who make policy proposals to governments do not necessarily have a strong interest in unemployment. In fact, as noted in the introduction, CGE analysis of IET usually ignores unemployment (labor market distortion). One of the purposes of this research is to highlight to the environmental economists that we should pay more attention to unemployment (labor market distortion) because ignoring it overlooks the important negative effect of IET.

It is generally recognized that IET is a desirable policy that benefits all participating regions, and so environmental economists are calling for its introduction. However, these calls ignore the indirect impact of IET on labor market distortions. We show that an analysis that does not account for such labor market distortions will likely overestimate the benefits of IET for permit exporters. Our analysis is valuable in the sense that there are few studies of the relation between IET and labor market distortions. However, at the same time, note that our model only considers limited types of labor market distortions. For example, unemployment is caused by various reasons such as structural unemployment, cyclical unemployment, short-term frictions, hidden unemployment, etc., which are not considered in our model. We will address these problems in future research.

Notes

In this paper, we focus on the welfare-decreasing international emissions trading. However, it is also shown that domestic emissions trading can be welfare-decreasing in a second-best setting. For example, Malueg (1990) shows that emissions trading can be welfare-decreasing when goods market is imperfectly competitive.

The rigidity of wages (and unemployment) is often referred to as an “imperfection” rather than a “distortion” (for example, Babiker and Eckaus 2007). However, we use the term distortion to represent not only the insufficient labor supply resulting from a labor tax but also the rigidity of wages.

See, for example, Layard et al. (2005).

For certain countries, unemployment rates are very high, for example, 17.4% for Spain, 13.4% for Brazil and 23.1% for Greece.

In the model with variable labor supply (Model VLAB), we assume that utility depends not only on consumption but also on leisure. See Sect. 3.2 for details.

For example, see Layard et al. (2005).

The existence of labor tax constrains labor supply below the optimal level. It is commonly known that emissions regulation in VLAB exerts an indirect effect, known as the “tax-interaction effect” (TI effect). The TI effect is as follows. Emissions regulation, such as carbon taxes and emissions trading, boosts the price level through the increase in energy prices. The increase in the price level affects the labor supply of the household by causing a decline in real wages. The household then faces a decline in its real wages and reduces its labor supply because of the substitution effect. This accelerates the decline in the labor supply, which is already at an insufficient level because of the presence of labor taxation, resulting in a worsening of the labor market distortion. In this way, labor market distortions expand through the indirect effect of emissions regulation on labor supply.

For details of the double dividend, see the survey in Bovenberg and Goulder (2002).

Layard et al. (2005) review the reasons for wage rigidity.

In some cases, emphasis is placed on the downward rigidity of the nominal wage. However, our study utilizes a real general equilibrium model in which nominal prices are not meaningful. Therefore, we focus on downward rigidity in the real wage.

Variable p is the consumer price index created from prices of final consumption goods. It is represented by \(p_r^U\) in the algebraic representation of the supplementary material.

Since \(LD = LS - UR = \left( {1 - \gamma } \right)LS\), we have \(\gamma = 1 - LD/LS\). Substituting this into (1), we obtain \(w/p = f\left( {1 - LD/LS} \right)\). This leads to \(\partial \left( {w/p} \right)/\partial LD = - f^{\prime}/LS > 0\). Then Eq. (1) is depicted as an upward-sloping curve in Fig. 5 where we assume that price level \(p\) is unity.

The only exception is the scenario of labor tax cuts in the sensitivity analysis.

\(\alpha\) is calibrated by \(\alpha = \left( {w_{0} /p_{0} } \right)/\left( {u_{0} } \right)^{ - \phi }\) where variables with subscript 0 are benchmark values.

These values are unemployment rates in the benchmark year of the simulation (year 2007).

In the sensitivity analysis, we analyze different reduction rates.

If governments can trade emissions permits internationally, they may have market power in the permit market. We would like to analyze such a situation in future research.

All simulation results are available from the authors upon request.

All numerical results from sensitivity analysis are provided in Takeda et al. (2015) or supplementary material.

One exception is India in Scenario lrd of S_WORLD.

References

Babiker MH, Eckaus RS (2007) Unemployment effects of climate policy. Environ Sci Policy 10:600–609

Babiker MH, Reilly J, Viguier L (2004) Is international emissions trading always beneficial? Energy J 25(2):33–56

Blanchflower DG, Oswald AJ (2005) The wage curve reloaded, May. NBER working paper series, 11338

Böhringer C, Wiegard W, Starkweather C, Ruocco A (2003) Green tax reforms and computational economics a do-it-yourself approach. Comput Econ 22:75–109

Bovenberg AL, Goulder LH (2002) Environmental taxation. In: Auerbach AJ, Feldstein M (eds) Handbook of public economics, chap. 21, vol 3. North-Holland, Amsterdam, pp 1471–1545

Brecher RA (1974) Minimum wage rates and the pure theory of international trade. Q J Econ 88(1):98–116. https://academic.oup.com/qje/article-lookup/doi/10.2307/1881796

Chateau J, Burniaux J-M (2008) An overview of the OECD ENV-linkages model. OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 653

Corden WM (1984) The normative theory of international trade. In: Jones RW, Kenen PB (eds) Handbook of international economics, Chap. 2, vol 1. North-Holland, Amstermdam, pp 63–130

Fischer C, Fox AK (2007) Output-based allocation of emissions permits for mitigating tax and trade interactions. Land Econ 83(4):575–599

Goulder LH (1995) Environmental taxation and the ‘double dividend’: a reader’s guide. Int Tax Public Finance 2:157–183

Guivarch C, Crassous R, Sassi O, Hallegatte S (2011) The costs of climate policies in a second best world with labour market imperfections. Clim Policy 11(1):768–788. https://doi.org/10.3763/cpol.2009.0012

Helpman E, Itskhoki O (2010) Labour market rigidities, trade and unemployment. Rev Econ Stud 77(3):1100–1137. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-937X.2010.00600.x

Hertel TW (ed) (1997) Global trade analysis: modeling and applications. Cambridge University Press, New York

Hutton JP, Ruocco A (1999) Tax reform and employment in Europe. Int Tax Public Finance 6:263–287

IPCC (2001) Climate change 2001: mitigation, summary for policy makers. IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) Third Assessment Report

Ishikawa J, Kiyono K, Yomogida M (2012) Is emission trading beneficial? Jpn Econ Rev 63(2):185–203

Jaffe J, Ranson M, Stavins RN (2009) Linking tradable permit systems: a key elements of emerging international climate policy architecture. Ecol Law Q 36:789–808

Küster R, Ellersdorfer I, Fahl U (2007) A CGE-analysis of energy policies considering labor market imperfections and technology specifications. Feem Working Papers "Note Di Lavoro" Series, 7.2007

Layard R, Nickell S, Jackman R (2005) Unemployment: macroeconomic performance and the labour market, 2nd edn. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Lee H (2008)The combustion-based CO2 emissions data for GTAP version 7 data base, December

Malueg DA (1990) Welfare consequences of emission credit trading programs. J Environ Econ Manag 18(1):66–77

OECD (2009) The economics of climate: change mitigation policies and options for global action beyond 2012. OECD

Paltsev SV (2001) The Kyoto agreement: regional and sectoral contributions to the carbon leakage. Energy J 22(4):53–79

Parry IWH (1995) Pollution taxes and revenue recycling. J Environ Econ Manag 29:64–77

Paltsev S, Reilly, JM, Jacoby HD, Eckaus RS, McFarland J, Sarofim M, Asadoorian M, Babiker MH (2005) The MIT emissions prediction and policy analysis (EPPA) model: version 4. MIT Joint Program on the Science and Policy of Global Change, Report No. 125, August 2005

Rutherford, TF, Light MK, Hern´andez G (2002) A dynamic general equilibrium model for tax policy analysis in Colombia. ARCHIVOS DE ECONOM´IA, Documento 189

Rutherford TF, Paltsev SV (2000) GTAPinGAMS and GTAP-EG: global datasets for economic research and illustrative models. September. Working Paper, University of Colorad, Department of Economics

Takeda S, Arimura T, Tamechika H, Fischer C, Fox AK (2014) Output-based allocation of emissions permits for mitigating carbon leakage for the Japanese economy. Environ Econ Policy Stud 16(1):89–110

Takeda S, Arimura T, Sugino M (2015) Labor market distortions and welfare-decreasing international emissions trading. No 1422, Working Papers, Waseda University, Faculty of Political Science and Economics, http://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:wap:wpaper:1422

Webster M, Paltsev S, Reilly J (2010) The hedge value of international emissions trading under uncertainty. Energy Policy 38(4):1787–1796

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank two anonymous referees for their helpful comments. This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Numbers JP15K03479 and JP18K01633 and by the Environment Research and Technology Development Fund (2-1707) of the Environmental Restoration and Conservation Agency and we would like to thank for their support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

OpenAccess This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Takeda, S., Arimura, T.H. & Sugino, M. Labor Market Distortions and Welfare-Decreasing International Emissions Trading. Environ Resource Econ 74, 271–293 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10640-018-00317-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10640-018-00317-4