Abstract

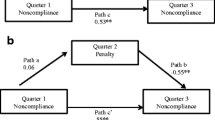

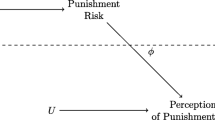

This study explores the specific deterrence generated by punishment in the context of regulatory violations with a focus on the distinction between upward revisions to future punishment parameters—likelihood and severity—and the experience of being penalized. In order to avoid the pitfalls of empirically analyzing actual choices made by regulated entities, e.g., measuring entities’ beliefs regarding the likelihood and size of future penalties, our study examines behavior associated with a stated choice scenario presented within a survey distributed to the environmental managers of facilities regulated under the US Clean Water Act. This choice of respondents strengthens the external validity of our empirical results. Based on a variety of statistical methods, our empirical results strongly and robustly reject the standard hypothesis that specific deterrence stems solely from upward revisions to punishment parameters while supporting the alternative hypothesis of experiential deterrence, whereby facilities focus on recent experiences to shape their compliance behavior.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Gray and Shimshack (2011) provide a recent survey on environmental enforcement.

See Cabinet Office Behavioural Insights Team (2012) for examples of how the UK government is using behavioral insights to reduce various kinds of fraud.

Earnhart and Friesen (2012) briefly study specific deterrence as part of a larger study of deterrence more generally. Their study focuses on corporate culture and individual characteristics of environmental manager respondents. In contrast, our paper focuses on specific deterrence, insight drawn from and contributions to the behavioral literature, and the identification of the regulated facilities’ characteristics that explain experiential deterrence.

Enforcement agencies rarely, if ever, announce the probability of detection. Severity too is unclear because the imposition and size of penalties is at the discretion of enforcement agencies and the courts, even though laws prescribe maximum penalty rates. Further, in the specific environmental context we study, penalties are rare and so opportunities to form accurate perceptions based on experiences are few.

This strategy could be interpreted as a form of Bayesian updating, as noted by one of the referees.

Haselhuhn et al. (2012) conjecture that experience may cause an upwards revision in the expected “affect” (essentially negative emotions) associated with being fined, which was initially underestimated. As a related study, Keller et al. (2006) study the role of affect in perceptions of flooding risk.

The chemical industry is not necessarily representative of all industrial sectors. Indeed, its unique attributes contribute to our interest in studying it. For example, some firms in the chemical industry have demonstrated an interest in promoting pollution reduction and prevention through efforts prompted by the Responsible Care program, which is a voluntary initiative supported by the American Chemistry Council.

As an additional criterion, facilities needed to being discharging pollutants into surface water bodies as opposed into systems operated by municipal wastewater treatment facilities. In technical terms, the sample included only direct dischargers while excluding industrial users. We exclude the latter category of polluters since they are most directly regulated by municipal wastewater treatment facilities.

We administered the survey over the phone yet mailed or faxed certain components of the survey instrument upon request. Prior to administering the survey, we refined the survey instrument based on feedback from a focus group of facilities, a pre-test sample of facilities, and a wastewater engineer.

Full details of the analysis on sample selection are available from the authors.

It is possible that respondents viewed these scenarios as unrealistic. Nevertheless, this issue does not affect our main result as long as any impact associated with this issue remains unchanged between the 2 years of the scenario.

Given this single distinction in ownership structure, we are able to supplement the survey-reported data on ownership structure using publicly available data, mainly from the Compustat Research Insight database, so that we posses ownership structure data on all survey respondents. Details on these publicly available data are available from the authors upon request.

The analysis aggregates the four-digit SIC codes into three broader sectoral categories: organic chemicals, inorganic chemicals, and “other” chemicals. The broad category of organic chemicals includes the following four-digit SIC codes: 2821, 2823, 2824, 2843, 2865, 2869, 2891, and 2899. The broad category of inorganic chemicals includes the following four-digit SIC codes: 2812, 2813, 2816, 2819, 2873, and 2874.

The lack of experience with fines was not unique to the survey respondents. In the period preceding the survey, very few US chemical manufacturing facilities permitted within the NPDES system received fines. Between 2001 and 2003, only one of the 1,681 chemical manufacturing facilities active in the NPDES system was fined. In 2000, only five of the 1,779 active facilities was fined, implying a mere 0.28 % chance of a facility getting fined. Thus, our sample of respondents appear fully representative of the relevant population in this regard.

While no fines were imposed on the survey respondent facilities, both informal enforcement actions and formal enforcement actions without fines were taken against several of the facilities in the survey sample.

In fact, it is not “rational” to improve maintenance given these parameters. Nevertheless, such behavior is consistent with the actual environmental management choices made by these facilities, whereby, 90 % of the studied chemical manufacturing facilities comply with their effluent limits in a given month and the average degree of over compliance is approximately 60 %. Previous studies also document the strong prevalence of compliance and indeed substantial overcompliance at these regulated facilities (Earnhart 2009; Earnhart and Glicksman 2011).

While the Scenario Year 2 indicator also captures the effects of any general learning about the scenarios, these effects are likely to be small for two reasons. First, the relevant parameters are fully described to the participants, the parameters remain the same in both years, and this lack of change is highlighted to the participants. Second, as discussed in Footnote 18, “rational” learning should influence the coefficient of the Scenario Year 2 indicator in the direction opposite to experiential deterrence.

As shown in Table 3, the sample size differs across the four models. Estimation of Models A1 and A2 while constraining the regression sample to remain the same as for Models A3 and A4 generates results that are highly similar to the results reported in Table 3. Thus, our conclusions are robust to this sample constraint.

Table 3 Random effects probit estimation of maintenance decision in years 1 and 2 of scenario Use of inspection indicator regressors, in lieu of inspection count regressors, generates results that are highly similar to those reported in Table 3 and support conclusions identical to those drawn in the text.

Estimation based on a regressor set that includes factors reflecting recent experiences with formal and informal enforcement generates insignificant coefficients for the enforcement-related regressors and results for the other regressors that are highly similar to those reported in Table 3. This alternative analysis considers the count of enforcement actions taken against particular facilities in the 12 months or 24 months preceding the survey’s completion. The considered formal enforcement actions do not impose fines.

In order to reduce the dimensionality of the regressor set, the analysis combines state inspections and federal inspections into a single regressor. In addition, the analysis is not able to assess the influence of experience with recent enforcement actions since none of the facilities included in the regression sample experienced enforcement in the 24 months preceding the survey’s completion.

Use of inspection indicator regressors, in leiu of inspection count regressors, generates results that are highly similar to those reported in Table 4.

References

Anton WRQ, Deltas G, Khanna M (2004) Incentives for environmental self-regulation and implications for environmental performance. J Environ Econ Manag 48:632–654

Arimura TH, Hibiki A, Katayama H (2008) Is a voluntary approach an effective environmental policy instrument? A case for environmental management systems. J Environ Econ Manag 55:281–295

Bebchuk LA, Kaplow L (1992) Optimal sanctions when individuals are imperfectly informed about the probability of apprehension. J Leg Stud 21:365–370

Becker GS (1968) Crime and punishment: an economic approach. J Political Econ 76:169–217

Bigoni M, Fridolfsson S-O, Le Coq C, Spagnolo G (2008) Risk aversion, prospect theory, and strategic risk in law enforcement: evidence from an antitrust experiment. SSE/EFI working paper series in economics and, Finance no 696

Cabinet Office Behavioural Insights Team (2012) Applying behavioural insights to reduce fraud, error and debt. Cabinet Office, UK

Earnhart D (2004a) Regulatory factors shaping environmental performance at publicly-owned treatment plants. J Environ Econ Manag 48(1):655–681

Earnhart D (2004b) Panel data analysis of regulatory factors shaping environmental performance. Rev Econ Stat 86(1):391–401

Earnhart D (2009) The influence of facility characteristics and permit conditions on the effects of environmental regulatory deterrence. J Regul Econ 36(3):247–273

Earnhart, D, Lana F (2012) Environmental management responses to punishment: specific deterrence and certainty versus severity of punishment. School of economics discussion paper no 463, University of Queensland, Australia

Earnhart D, Glicksman R (2011) Pollution limits and polluters’ efforts to comply: the role of government monitoring and enforcement. Stanford University Press, Palo Alto

Eckert H (2004) Inspections, warnings, and compliance: the case of petroleum storage regulation. J Environ Econ Manag 47(2):232–259

EPA (1997) Chemical industry national environmental baseline report 1990–1994. Office of enforcement and compliance assurance, environmental protection agency, EPA 305-R-96-002, October 1997

EPA (1999), EPA/CMA root cause analysis pilot project: an industry survey, environmental protection agency, EPA-305-R-99-001, May 1999

Garoupa N (2003) Behavioral economic analysis of crime: a critical review. Eur J Law Econ 15:5–15

Gray WB, Shimshack JP (2011) The effectiveness of environmental monitoring and enforcement: a review of the empirical evidence. Rev Environ Econ Policy 5:3–24

Harrington W (1988) Enforcement leverage when penalties are restricted. J Public Econ 37:29–53

Haselhuhn M, Pope D, Schweitzer M, Fishman P (2012) The impact of personal experience on behavior: evidence from video-rental fines. Manag Sci 58:52–61

Jolls C, Sunstein CR, Thaler R (1998) A behavioral approach to law and economics. Stanf Law Rev 50:1471–1550

Kaplow L (1990) Optimal deterrence uninformed individuals, and acquiring information about whether acts are subject to sanctions. J Law Econ Organ 6:93–128

Keller C, Siegrist M, Gutscher H (2006) The role of the affect and availability heuristics in risk communication. Risk Anal 26:631–639

Kunreuther H, Pauly M (2006) Insurance decision-making and market behavior. Found Trends Microecon 1:63–127

Lochner L (2007) Individual perceptions of the criminal justice system. Am Econ Rev 97:444–460

Maddala GS (1983) Limited-dependent and qualitative variables in econometrics. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Malik AS (1990) Markets for pollution control when firms are noncompliant. J Environ Econ Manag 18:97–106

Newell B, Rakow T (2007) The role of experience in decisions from description. Psychon Bull Rev 14:1133–1139

Polinsky AM, Rubinfeld D (1991) A model of optimal fines for repeat offenders. J Public Econ 46:291–306

Polinsky AM, Shavell S (1998) On offense history and the theory of deterrence. Int Rev Law Econ 18:305–324

Polinsky AM, Shavell S (2000) The economic theory of public enforcement of law. J Econ Lit 38:45–76

Sah RK (1991) Social osmosis and patterns of crime. J Political Econ 99:1272–1295

Scholz JT, Gray WB (1990) OSHA enforcement and workplace injuries: a behavioral approach to risk assessment. J Risk Uncertain 3:283–305

Shimshack JP, Ward MB (2005) Regulator reputation enforcement, and environmental compliance. J Environ Econ Manag 50:519–540

Simonsohn U, Karlsson N, Loewenstein G, Ariely D (2008) The tree of experience in the forest of information: overweighing experienced relative to observed information. Games Econ Behav 62:263–286

Thorton D, Gunningham NA, Kagan RA (2005) General deterrence and corporate environmental behaviour. Law Policy 27(2):262–288

Tversky A, Kahneman D (1974) Judgment under uncertainty: heuristics and biases. Science 185:1124–1131

Weinstein ND (1980) Unrealistic optimism about future life events. J Pers Soc Psychol 39:806–820

Weinstein ND, Lyon JE, Rothman AJ, Cuite CL (2000) Changes in perceived vulnerability following natural disaster. J Soc Clin Psychol 19:372–395

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Earnhart, D., Friesen, L. Can Punishment Generate Specific Deterrence Without Updating? Analysis of a Stated Choice Scenario. Environ Resource Econ 56, 379–397 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10640-013-9652-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10640-013-9652-0