Abstract

Learning analytics provides a novel means to support the development and growth of students into self-regulated learners, but little is known about student perspectives on its utilization. To address this gap, the present study proposed the following research question: what are the perceptions of higher education students on the utilization of a learning analytics dashboard to promote self-regulated learning? More specifically, this can be expressed via the following threefold sub-question: how do higher education students perceive the use of a learning analytics dashboard and its development as promoting the (1) forethought, (2) performance, and (3) reflection phase processes of self-regulated learning? Data for the study were collected from students (N = 16) through semi-structured interviews and analyzed using a qualitative content analysis. Results indicated that the students perceived the use of the learning analytics dashboard as an opportunity for versatile learning support, providing them with a means to control and observe their studies and learning, while facilitating various performance phase processes. Insights from the analytics data could also be used in targeting the students’ development areas as well as in reflecting on their studies and learning, both individually and jointly with their educators, thus contributing to the activities of forethought and reflection phases. However, in order for the learning analytics dashboard to serve students more profoundly across myriad studies, its further development was deemed necessary. The findings of this investigation emphasize the need to integrate the use and development of learning analytics into versatile learning processes and mechanisms of comprehensive support and guidance.

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Promoting students to become autonomous, self-regulated learners is a fundamental goal of education (Lodge et al., 2019; Puustinen & Pulkkinen, 2001). The importance of doing so is particularly highlighted in higher education (HE) contexts that strive to prepare its students for highly demanding and autonomous expert tasks (Virtanen, 2019). In order to perform successfully in diverse educational and professional settings, students need to take an active, self-initiated role in managing their learning processes, thereby assuming primary responsibility for their educational pursuits. Self-regulated learning (SRL) invites students to actively monitor, control, and regulate their cognition, motivation, and behavior in relation to their learning goals and contextual conditions (Pintrich, 2000). In an effort to create a favorable foundation for the development of SRL, many HE institutions have begun to explore and exploit the potential of emerging educational technologies, such as learning analytics (LA).

Despite the growing interest in adopting LA for educational purposes (Van Leeuwen et al., 2022), little is known about students’ perspectives on its utilization (Jivet et al., 2020; Wise et al., 2016). Additionally, there is only limited evidence on using LA to support SRL (Heikkinen et al., 2022; Jivet et al., 2018; Matcha et al., 2020; Viberg et al., 2020). Thus, more research is inevitably needed to better understand how students themselves consider the potential of analytics applications from the perspective of SRL. Involving students in the development of LA is particularly important, as they represent primary stakeholders targeted to benefit from its utilization (Dollinger & Lodge, 2018; West et al., 2020). LA should not only be developed for users but also with them in order to adapt its potential to their needs and expectations (Dollinger & Lodge, 2018; Klein et al., 2019).

LA is thought to provide a promising means to enhance student SRL by harnessing the massive amount of data stored in educational systems and facilitating appropriate means of support (Lodge et al., 2019). It is generally defined as “the measurement, collection, analysis and reporting of data about learners and their contexts, for purposes of understanding and optimising learning and the environments in which it occurs” (Conole et al., 2011, para. 4). The reporting of such data is typically conducted through learning analytics dashboards (LADs) that aggregate diverse types of indicators about learners and learning processes in a visualized form (Corrin & De Barba, 2014; Park & Jo, 2015; Schwendimann et al., 2017). Recently, there has been a rapid movement into LADs that present analytics data directly to students themselves (Schwendimann et al., 2017; Teasley, 2017; Van Leeuwen et al., 2022). Such analytics applications generally aim to provide students with insights into their study progress as well as support for optimizing learning outcomes (Molenaar et al., 2019; Sclater et al., 2016; Susnjak et al., 2022).

The purpose of this qualitative study is to examine how HE students perceive the use and development of an LAD to promote the different phases and processes of SRL. Instead of taking a course-level approach, this study addresses a less-examined study path perspective that covers the entirety of studies, from the start of an HE degree to its completion. A specific emphasis is placed on such an LAD that students could use both independently across studies and together with their tutor teachers as a component of educational guidance. As analytics applications are largely still under development (Sclater et al., 2016), and mainly in the exploratory phase (Schwendimann et al., 2017; Susnjak et al., 2022), it is essential to gain an understanding of how students perceive the use of these applications as a form of learning support. Preparing students to become efficient self-regulated learners is increasingly—and simultaneously—a matter of helping them develop into efficient users of analytics data.

2 Theoretical framework

2.1 Enhancing SRL in HE

SRL, which has been the subject of wide research interest over the last two decades (Panadero, 2017), is referred to as “self-generated thoughts, feelings, and actions that are planned and cyclically adapted to the attainment of personal goals” (Zimmerman, 1999, p. 14). Self-regulated students are proactive in their endeavors to learn, and they engage in diverse, personally initiated metacognitive, motivational, and behavioral processes to achieve their goals (Zimmerman, 1999). They master their learning through covert, cognitive means but also through behavioral, social, and environmental approaches that are reciprocally interdependent and interrelated (Zimmerman, 1999, 2015), thus emphasizing the sociocognitive views on SRL (Bandura, 1986).

When describing and modelling SRL, researchers have widely agreed on its cyclical nature and its organization into several distinct phases and processes (Panadero, 2017; Puustinen & Pulkkinen, 2001). In the well-established model by Zimmerman and Moylan (2009), SRL occurs in the cyclic phases of forethought, performance, and self-reflection that take place before, during, and after students’ efforts to learn. In the forethought phase, students prepare themselves for learning and approach the learning tasks through the processes of planning and goal setting, and the activation of self-motivation beliefs, such as self-efficacy perceptions, outcome expectations, and personal interests. Next, in the performance phase, they carry out the actual learning tasks and make use of self-control processes and strategies, such as self-instruction, time management, help-seeking, and interest enhancement. Moreover, they keep records of their performance and monitor their learning, while promoting the achievement of desired goals. In the final self-reflection phase, students participate in the processes of evaluating their learning and reflecting on the perceived causes of their successes and failures, which typically results in different types of cognitive and affective self-reactions as responses to such activity. This phase also forms the basis for the approaches to be adjusted for and applied in the subsequent forethought phase, thereby completing the SRL cycle. The model suggests that the processes in each phase influence the following ones in a cyclical and interactive manner and provide feedback for subsequent learning efforts (Zimmerman & Moylan, 2009; Zimmerman, 2011). Participation in these processes allows students to become self-aware, competent, and decisive in their learning approaches (Kramarski & Michalsky, 2009).

Although several other prevalent SRL models with specific emphases also exist (e.g., Pintrich, 2000; Winne & Hadwin, 1998; for a review, see Panadero, 2017), the one presented above provides a comprehensive yet straightforward framework for identifying and examining the key phases and processes related to SRL (Panadero & Alonso-Tapia, 2014). Developing thorough insights into the student SRL is especially needed in an HE context, where the increase in digitized educational settings and tools requires students to manage their learning in a way that is autonomous and self-initiated. When pursuing an HE degree, students are expected to engage in the cyclical phases and processes of SRL as a continuous effort throughout their studies. Involvement in SRL is needed not only to successfully perform a single study module, course, or task but also to actively promote the entirety of studies throughout semesters and academic years. It therefore plays a central role in the successful completion of HE studies.

From the study path perspective, the forethought phase requires HE students to be active in the directing and planning of their studies and learning—that is, setting achievable goals, making detailed plans, finding personal interests, and trusting in their abilities to complete the degree. The performance phase, in turn, invites students to participate in the control and observation of their studies and learning. While completing their studies, they must regularly track study performance, visualize relevant study information, create functional study environments, maintain motivation and interest, and seek and receive productive guidance. The reflection phase, on the other hand, involves students in evaluating and reflecting on their studies and learning—that is, analyzing their learning achievements and processing resulting responses. These activities typically occur as overlapping, cyclic, and connected processes and as a continuum across studies. Additionally, the phases may appear simultaneously, as students strive to learn and receive feedback from different processes (Pintrich, 2000). The processes may also emerge in more than one phase (Panadero & Alonso-Tapia, 2014), and boundaries between the phases are not always that precise.

SRL is shown to benefit HE students in various ways. Research has evidenced, for instance, that online students who use their time efficiently, are aware of their learning behavior, think critically, and show efforts to learn despite challenges are likely to achieve academic success when studying in online settings (Broadbent & Poon, 2015). SRL is also shown to contribute to many non-academic outcomes in HE blended environments (for a review, see Anthonysamy et al., 2020). Despite this importance, research (e.g., Azevedo et al., 2004; Barnard-Brak et al., 2010) has indicated that students differ in their ways to self-regulate, and not all are competent self-regulated learners by default. As such, many students would require and benefit from support to develop their SRL (Moos, 2018; Wong et al., 2019).

Supporting student SRL is generally considered the responsibility of a teaching staff (Callan et al., 2022; Kramarski, 2018). It can also be a specific task given to tutor teachers assigned to each student or to a group of students for particular academic years. Sometimes referred to as advisors, they are often teachers of study programs who aim to help students in decision-making, study planning, and career reflection (De Laet et al., 2020), while offering them guidance and support for the better management of learning. In recent years, efforts have also been made to promote student SRL with educational technologies such as LA (e.g., Marzouk et al., 2016; Wise et al., 2016). LA is used to deliver insights for students themselves to better self-regulate their learning (e.g., Jivet et al., 2021; Molenaar et al., 2019), and also to facilitate the interaction between students and guidance personnel (e.g., Charleer et al., 2018). It is generally thought to promote the development of future competences needed by students in education and working life (Kleimola & Leppisaari, 2022), and to offer novel insights into their motivational drivers (Kleimola et al., 2023).

2.2 LA as a potential tool to promote SRL

Much of the recent development in the field of LA has focused on the design and implementation of LADs. In general, their purpose is to support sensemaking and encourage students and teachers to make informed decisions about learning and teaching processes (Jivet et al., 2020; Verbert et al., 2020). Schwendimann and colleagues (2017) refer to an LAD as a “display that aggregates different indicators about learner(s), learning process(es) and/or learning context(s) into one or multiple visualizations” (p. 37). Such indicators may provide information, for instance, about student actions and use of learning contents on a learning platform, or the results of one’s learning performance, such as grades (Schwendimann et al., 2017). Data can also be extracted from educational institutions’ student information systems to provide students with snapshots of their study progress and access to learning support (Elouazizi, 2014). While visualizations enable intuitive and quick interpretations of educational data (Papamitsiou & Economides, 2015), they additionally require careful preparation, as not all users may necessarily interpret them uniformly (Aguilar, 2018).

LADs can target various stakeholders, and recently there has been a growing interest in their development for students’ personal use (Van Leeuwen et al., 2022). Such displays, also known as student-facing dashboards, are thought to increase students’ knowledge of themselves and to assist them in achieving educational goals (Eickholt et al., 2022). They are also believed to promote student autonomy by encouraging students to take control of their learning and by supporting their intrinsic motivation to succeed (Bodily & Verbert, 2017). However, simply making analytics applications available to students does not guarantee that they will be used productively in terms of learning (Wise, 2014; Wise et al., 2016). Moreover, they may not necessarily cover or address the relevant aspects of learning (Clow, 2013). Thus, to promote the widespread acceptance and adoption of LADs, it is crucial to consider students’ perspectives on their use as a means of learning support (Divjak et al., 2023; Schumacher & Ifenthaler, 2018). If students’ needs are not adequately examined and met, such analytics applications may fail to encourage or even hinder the process of SRL (Schumacher & Ifenthaler, 2018).

Although previous research on students’ perceptions of LA to enhance their SRL appears to be limited, some studies have addressed such perspectives. Schumacher and Ifenthaler (2018) found that HE students appreciated LADs that help them plan and initiate their learning activities with supporting elements such as reminders, to-do lists, motivational prompts, learning objectives, and adaptive recommendations, thus promoting the forethought phase of SRL. The students in their study also expected such analytics applications to support the performance phase by providing analyses of their current situation and progress towards goals, materials to meet their individual learning needs, and opportunities for learning exploration and social interaction. To promote the self-reflection phase, the students anticipated LADs to allow for self-assessment, real-time feedback, and future recommendations but were divided as to whether they should receive comparative information about their own or their peers’ performance (Schumacher & Ifenthaler, 2018). Additionally, the students desired analytics applications to be holistic and advanced, as well as adaptable to individual needs (Schumacher & Ifenthaler, 2018).

Somewhat similar notions were made by Divjak and colleagues (2023), who discovered that students welcomed LADs that promote short-term planning and organization of learning but were wary of making comparisons or competing with peers, as they might demotivate learners. Correspondingly, De Barba et al. (2022) noted that students perceived goal setting and monitoring of progress from a multiple-goals approach as key features in LADs, but they were hesitant to view peer comparisons, as they could promote unproductive competition between students and challenge data privacy. In a similar vein, Rets et al. (2021) reported that students favored LADs that provide them with study recommendations but did not favor peer comparison unless additional information was included. Roberts et al. (2017), in turn, stressed that LADs should be customizable by students and offer them some level of control to support their SRL. Silvola et al. (2023) found that students perceived LADs as supportive for their study planning and monitoring at a study path level but also associated some challenges with them in terms of SRL. Further, Bennett (2018) found that students’ responses to receiving analytics data varied and were highly individual. There were different views, for instance, on the potential of analytics to motivate students: although it seemed to inspire most students, not all students felt the same way (Bennett, 2018; see also Corrin & De Barba, 2014; Schumacher & Ifenthaler, 2018). Moreover, LADs were reported to evoke varying affective responses in students (Bennett, 2018; Lim et al., 2021).

To promote student SRL, it is imperative that LADs comprehensively address and support all phases of SRL (Schumacher & Ifenthaler, 2018). However, a systematic literature review conducted by Jivet et al. (2017) indicated that students were often offered only limited support for goal setting and planning, and comprehensive self-monitoring, as very few of the LADs included in their study enabled the management of self-set learning goals or the tracking of study progress over time. According to Jivet et al. (2017), this might indicate that most LADs were mainly harnessed to support the reflection and self-evaluation phase of SRL, as the other phases were mostly ignored. Somewhat contradictory results were obtained by Viberg et al. (2020), whose literature review revealed that most studies aiming to measure or support SRL with LA were primarily focused on the forethought and performance phases and less on the reflection phase. Heikkinen et al. (2022) discovered that not many of the studies combining analytics-based interventions and SRL processes covered all phases of SRL.

It appears that further development is inevitably required for LADs to better promote student SRL as a whole. Similarly, there is a demand for their tight integration into pedagogical practices and learning processes to encourage their productive use (Wise, 2014; Wise et al., 2016). One such strategy is to use these analytics applications as a part of guidance activity and as a joint tool for both students and guidance personnel. In the study by Charleer et al. (2018), the LAD was shown to trigger conversations and to facilitate dialogue between students and study advisors, improve the personalization of guidance, and provide insights into factual data for further interpretation and reflection. However, offering students access to an LAD only during the guidance meeting may not be sufficient to meet their requirements for the entire duration of their studies. For instance, Charleer and colleagues (2018) found that the students were also interested in using the LAD independently, outside of the guidance context. Also, it seems that encouraging students to actively advance their studies with such analytics applications necessitates a student-centered approach and holistic development through research. According to Rets et al. (2021), there is a particular call for qualitative insights, as many previous LAD studies that included students have primarily used quantitative approaches (e.g., Beheshitha et al., 2016; Divjak et al., 2023; Kim et al., 2016).

2.3 Research questions

The purpose of this qualitative study is to examine how HE students perceive the utilization of an LAD in SRL. A specific emphasis was placed on its utilization as part of the forethought, performance, and reflection phase processes, considered central to student SRL. The main research question (RQ) and the threefold sub-question are as follows:

RQ: What are the perceptions of HE students on the utilization of an LAD to promote SRL?

-

How do HE students perceive the use of an LAD and its development as promoting the (1) forethought, (2) performance, and (3) reflection phase processes of SRL?

3 Methods

3.1 Context

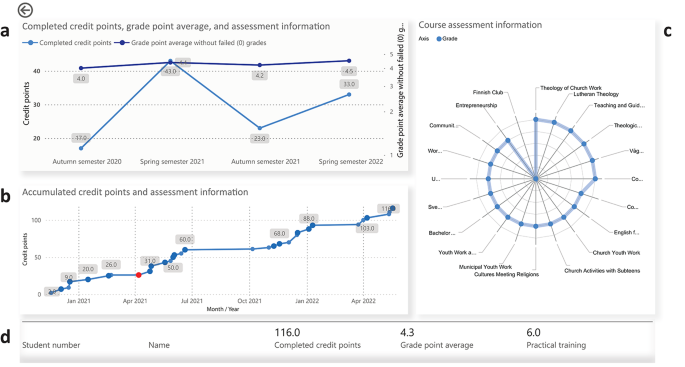

The study was conducted in a university of applied sciences (UAS) in Finland that had launched an initial version of an LAD to be piloted together with its students and tutor teachers as a part of the guidance process. The LAD was descriptive in nature and consisted of commonly available analytics data and simple analytics indicators showing an individual student’s study progress and success in a study path. As is typical for descriptive analytics, it offered insights to better understand the past and present (Costas-Jauregui et al., 2021) while informing the future action (Van Leeuwen et al., 2022). The data were extracted from the UAS’ student information system and presented using Microsoft Power BI tools. No predictive or comparative information was included. The main display of the LAD consisted of three data visualizations and an information bar (see Fig. 1, a–d), all presented originally in Finnish. Each visualization could also be expanded into a single display for more accurate viewing.

First, the LAD included a data visualization that illustrated a student’s study progress and success per semester using a line chart (Fig. 1, a). It displayed the scales for total number of credit points (left) and grade point averages (right) for courses completed on a semester timeline. Data points on the chart displayed an individual student’s study performance with respect to these indicators in each semester and were connected to each other with a line. Pointing to one of these data points also opened a data box that indicated the student name and information about courses (course name, scope, grade, assessment date) from which the credit points and grade point averages were obtained.

Second, the LAD contained another type of line chart that indicated a student’s individual study progress over time in more detail (Fig. 1, b). The chart displayed a timeline with three-month periods and illustrated a scale for the accumulated credit points. Data points on the chart indicated the accumulated number of credit points obtained from the courses and appeared in blue if the student had passed the course(s) and in red if the student had failed the course(s) at that time. As with the line chart above it, the data points in this chart also provided more detailed information about the courses behind the credit points and were intertwined with a line.

Third, the LAD offered information related to a student’s study success through a radar chart (Fig. 1, c). The chart represented the courses taken by the student and displayed a scale for the grades received from them. The lowest grade was placed in the center of the chart and the highest one on its outer circle. The grades in between were scaled on the chart accordingly, and the courses performed with a similar grade were displayed close to each other. Data points on the chart represented the grades obtained from numerically evaluated courses and were merged with a line. Each data point also had a data box with the course name and the grade obtained.

Fourth, the LAD included an information bar (Fig. 1, d) that displayed the student number and the student name (removed from the figure), the total number of accumulated credit points, the grade point average for passed courses, and the amount of credit points obtained from practical training.

The LAD was piloted in authentic guidance meetings in which a tutor teacher and a student discussed topical issues related to the completion of studies. Such meetings were a part of the UAS’ standard guidance discussions that were typically held 1–2 times during the academic year, or more often if needed. In the studied meetings, the students and tutor teachers collectively reviewed the LAD to support the discussion. Only the tutor teachers were commonly able to access the LAD, as it was still under development and in the pilot phase. However, the students could examine its use as presented by the tutor teacher. In addition to the LAD, the meeting focused on reviewing the student’s personal study plan, which contained information about their studies to be completed and could be viewed through the student information system. Most of the meetings were organized online, and their duration varied according to an individual student’s needs. A researcher (first author) attended the meetings as an observer.

3.2 Participants and procedures

Participants were HE students (N = 16) pursuing a bachelor’s degree at the Finnish University of Applied Sciences (UAS), ranging from 21 to 49 years of age (mean = 30.38, median = 29.5); 11 (68.75%) were female, and 5 (31.25%) were male. HE studies commenced between 2016 and 2020, and comprised different academic fields, including business administration, culture, engineering, humanities and education, and social services and health care. Depending on the degree, study scope ranged from 210 to 240 ECTS credit points, which take approximately three and a half to four years to complete. However, the students could also proceed at a faster or slower pace under certain conditions. The students were selected to represent different study fields and study stages, and to have studied for more than one academic year. Informed consent to participate in the study was obtained from all students, and their participation was voluntary. The research design was approved by the respective UAS.

Data for this qualitative study was collected through semi-structured, individual student interviews conducted in April–September 2022. To address certain topics in each interview, an interview guide was used. The interview questions incorporated into the guide were tested in two student test interviews to simulate a real interview situation and to assure intelligibility, as also suggested by Chenail (2011). Findings indicated that the questions were largely usable, functional, and understandable, but some had to be slightly refined to ensure their conciseness and to improve clarity and familiarity of expressions vis-à-vis the target group. Also, the order of questions was partly reshaped to support the flow of discussion.

In the interviews, the students were asked to provide information about their demographic and educational backgrounds as well as their overall opinions of educational practices and the use of LA. In particular, they were invited to share their views on the use of the piloted LAD and its development as promoting different phases and processes of SRL. Students’ perceptions were generally based on the assumption that they could use the LAD both independently during their studies and collectively with their tutor teachers as a component of the guidance process.

Interviews were conducted immediately or shortly after the guidance meeting. Interview duration ranged from 42 to 70 min. The graphical presentation of the LAD was commonly shown to the students to provide stimuli and evoke discussion, as suggested by Kwasnicka et al. (2015). The interviews were conducted by the same researcher (first author) who observed the guidance meetings. They were primarily held online, and only one was organized face-to-face. All interviews were video recorded for subsequent analysis.

3.3 Data analysis

Interview recordings were transcribed verbatim, accumulating a total of 187 pages of textual material for analysis (Times New Roman, 12-point font, line spacing 1). A qualitative content analysis method was used to analyze the data (see Mayring, 2000; Schreier, 2014) to enhance in-depth understanding of the research phenomenon and to inform practical actions (Krippendorf, 2019). Also, data were approached both deductively and inductively (see Elo & Kyngäs, 2008; Merriam & Tisdell, 2016), and the analysis was supported using the ATLAS.ti program.

Analysis began with a thorough familiarization with the data in order to develop a general understanding of the students’ perspectives. First, the data were deductively coded using Zimmerman and Moylan’s (2009) SRL model as a theoretical guide for analysis and as applied to the study path perspective. All relevant units of analysis—such as paragraphs, sentences, or phrases that addressed the use of the LAD or its development in relation to the processes of SRL presented in the model—were initially identified from the data, and then sorted into meaningful units with specific codes. The focus was placed on instances in the data that were applicable and similar to the processes represented in the model, but the analysis was not limited to those that fully corresponded to them. The preliminary analysis involved several rounds of coding that ultimately led to the formation of main categories, grouped into the phases of SRL. The forethought phase consisted of processes that emphasized the planning and directing of studies and learning with the LAD. The performance phase, in turn, involved processes that addressed the control and observation of studies and learning through the LAD. Finally, the reflection phase included processes that focused on evaluating and reflecting on studies and learning with the LAD.

Second, the data were approached inductively by examining the use of the LAD and its development as distinct aspects within each phase and process of SRL (i.e., the main categories). The aim was, on the one hand, to identify how the use of the LAD was considered to serve the students in the phases and processes of SRL in its current form, and on the other hand, how it should be improved to better support them. The analysis not only focused on the characteristics of the LAD but also on the practices that surrounded its use and development. The units of analysis were first condensed from the data and then organized into subcategories for similar units. As suggested by Schreier (2014), the process was continued until a saturation point was reached—that is, no additional categories could be found. As a result, subcategories for all of the main categories were identified.

Following Schreier’s (2014) recommendation, the categories were named and described with specific data examples. Additionally, some guidelines were added to highlight differences between categories and to avoid overlap. Using parts of this categorization framework as a coding scheme, a portion of the data (120 text segments) was independently coded into the main categories by the first and second authors. The results were then compared, and all disagreements were resolved through negotiation until a shared consensus was reached. After minor changes were made to the coding scheme, the first author recoded all data. The number of students who had provided responses to each subcategory was counted and added to provide details on the study. For study integrity, the results are supported by data examples with the students’ aliases and the study fields they represented. The quotations were translated from Finnish to English.

4 Results

The results are reported by first answering the threefold sub-question, that is, how do HE students perceive the use of an LAD and its development as promoting the (1) forethought, (2) performance, and (3) reflection phase processes of SRL. The subsequent results are then summarized to address the main RQ, that is, what are the main findings on HE students’ perceptions on the utilization of an LAD to promote SRL.

4.1 LAD as a part of the forethought phase processes

The students perceived the use of the LAD and its development as related to the forethought phase processes of SRL through the categorization presented in Table 1 below.

Regarding the process of goal setting, almost all students (n = 15) emphasized that the use of the LAD promoted the targeting of goal-oriented study completion and competence development. Analytics indicators—such as grades, grade point averages, and accumulated credit points—adequately informed the students of areas they should aim for, further improve, or put more effort into. Only one student (n = 1) considered the analytics data too general for establishing goals. However, some students (n = 7) specifically mentioned their desire to set and enter individual goals in the LAD. The students were considered to have individual intentions, which should also be made visible in the LAD:

For example, someone might complete [their studies] in four years, someone might do [them] even faster, so maybe in a way that there is the possibility…to set…that, well, I want or my goal is to graduate in this time, and then it would kind of show in it. (Sophia, Humanities and Education student)

Moreover, some students (n = 6) wanted to obtain information on the degree program’s overall target times, study requirements, or pace recommendations through the LAD.

In relation to the process of study planning, the use of the LAD provided many students (n = 8) grounds to plan and structure the promotion and completion of their studies, such as which courses and types of studies to choose, and what kind of study pace and schedule to follow. However, an even greater set of students (n = 12) hoped that the LAD could provide them with more sophisticated tools for planning. For instance, it could inform them about studies to be completed, analyze their study performance in detail, or make predictions for the future. Moreover, it should offer them opportunities to choose courses, make enrollments, set schedules, get reminders, and take notes. One example of such an advanced analytics application was described as follows: ‟It would be a bit like a conversational tool with the student as well, that you would first put…your studies in the program, so it would [then] remind you regularly that hey, do this” (James, Humanities and Education student).

When discussing the use of the LAD, most students (n = 12) emphasized the critical role of personal interests and preferences, which was found to not only guide studying and learning in general but to also drive and shape the utilization of the LAD. According to the students, using such an analytics application could particularly benefit those students who, for instance, prefer monitoring of study performance, perceive information in a visualized form, are interested in analytics or themselves, or find it relevant for their studies. Prior familiarization was also considered useful: ‟Of course, there are those who use this kind of thing more and those who use this kind of thing in daily life, so they could especially benefit from this, probably more than I do” (Olivia, Social Services and Health Care student). Even though the LAD was considered to offer pertinent insights for many types of learners, it might not be suitable for all. For instance, it could be challenging for some students to comprehend analytics data or to make effective use of them in their studies. In the development of the LAD, such personal aspects should be noted. The students (n = 7) believed the LAD might better adapt to students’ individual needs if it allows them to customize its features and displays or to use it voluntarily based on one’s personal interests and needs.

When describing the use of LAD, half of the students (n = 8) discussed its connections with self-efficacy. Making use of analytics data appeared to strengthen the students’ beliefs in their abilities to study and learn in a targeted manner, even if their own feelings suggested otherwise. As one of the students stated:

It’s nice to see that progress, that it has happened although it feels that it hasn’t. So, you can probably set goals based on [an idea] that you’re likely to progress, you could set [them] that you could graduate sometime. (Emma, Engineering student)

On the other hand, the use of the LAD also seemed to require students to have sufficient self-efficacy. It was perceived as vital especially when the analytics data showed unfavorable study performance, such as failed or incomplete courses, or gaps in the study performance with respect to peers. One student (n = 1) suggested that the LAD could include praises as evidence of and support for appropriate study performance. Such incentives may help improve the students’ self-confidence as learners. Apart from this, however, the students had no other recommendations for developing the use of the LAD to support self-efficacy.

4.2 LAD as a part of the performance phase processes

The students discussed the use of the LAD and its development in relation to the performance phase processes of SRL according to the categories described in Table 2 below.

The students (n = 16) widely agreed that using the LAD benefited them in the process of metacognitive monitoring. By indicating the progress and success of study performance, the LAD was thought to be well suited for observing the course of studies and the development of competences. Moreover, it helped the students to gain awareness of their individual strengths and weaknesses, as well as successes and failures, in a study path. Tracking individual study performance was also found to contribute to purposeful study completion, as the following data example demonstrates:

It’s important especially when there is a target time to graduate, so of course you must follow and stay on track in many ways as there are many such pitfalls to easily fall into, [and] as I’ve fallen quite many times, it’s good [to monitor]. (Sarah, Culture student)

Additionally, the insights of monitoring could be used in future job searches to provide information about acquired competences to potential employers. The successful promotion of studies was generally perceived to require regular monitoring by both students and their educators. However, one of the students considered it a particular responsibility of the students themselves, as the studies were completed at an HE level and were thus voluntary for them. To provide more in-depth insights, many students (n = 12) recommended the incorporation of a course-level monitoring opportunity in the LAD. More detailed information was needed, for instance, about course descriptions, assignments completed, and grades received. The rest of the students (n = 4), however, wanted to keep the course-level monitoring within the learning management system. One of them stated that it could also be a place through which the students could use the LAD. Some students (n = 6) emphasized the need to reconsider current assessment practices to enable better tracking of study performance. Specifically, assessments could be made in greater detail and grades given immediately after course completion. The variation in scales and time points of assessments between the courses and degree programs posed potential challenges for monitoring, thus prompting the need to unify educational practices at the organizational level.

As an activity closely related to metacognitive monitoring, the process of imaging and visualizing was emphasized by the students as helping them to advance in their educational pursuits. Most students (n = 15) mentioned that using the LAD allowed them to easily image their study path and clarify their study situation. As one of them stated, ‟This is quite clear, this like, that you can see the overall situation with a quick glance” (Anna, Business Administration student). The visualizations were perceived as informative, tangible, and understandable. However, they were also thought to carry the risk of students neglecting some other relevant aspects of studying and learning in the course of attracting such focused attention. Although the visualizations were generally considered clear, some students (n = 11) noted that they could be further improved to better organize the analytics data. For instance, the students suggested the attractive use of colors and the categorization of different types of courses. Visual symbols, in turn, may be particularly effective in course-level data. Technical aspects should also be carefully considered to avoid false visualizations.

Regarding the process of environmental structuring, the LAD appeared to be a welcome addition to the study toolkit and overall study environment. A few students (n = 4) considered it appropriate to utilize the LAD as a separate PowerBI application alongside other (Microsoft O365) study tools, but they also felt that it could be utilized through other systems if necessary. However, one student (n = 1) raised the need for overall system integrations and some students (n = 8) expressed a specific wish to use the LAD as an integrated part of the student information system that was thought to improve its accessibility. A few students (n = 6) also wanted to receive some additional analytics data as related to the information stored in such a system. For instance, the students could be informed about their study progress or offered feedback on their overall performance in relation to the personal study plan. Other students (n = 10), in turn, did not consider the need for this or did not mention it. It was generally emphasized that the LAD should remain sufficiently clear and simple, as too much information can make its use ineffective:

I think there is just enough information in this. Of course, if you would want to add something small, you could, but I don’t know how much, because I feel that when there is too much information, so it’s a bit like you can’t get as much out of it as you could get. (Olivia, Social Services and Health Care student)

Moreover, the analytics data must be kept private and protected. The students generally desired personal access to the LAD; if given such an opportunity, almost all (n = 15) believed they would utilize it in the future, and only one (n = 1) was unsure about this prospect. The analytics data were believed to be of particular use when studies were actively promoted. Hence they should be made available to the students from the start of their studies.

Regarding the process of interest and motivation enhancement, all students (n = 16) mentioned that using the LAD stimulated their interest or enhanced their motivation, although to varying degrees. For some students, a general tracking of studies was enough to encourage them to continue their pursuits, while others were particularly inspired by seeing either high or low study performance. The development of motivation and interest was generally thought to be a hindrance if the students perceived the analytics data as unfavorable or lacking essential information. As one of students mentioned, ‟If your [chart] line was downward, and if there were only ones and zeros or something like that, it could in a way decrease the motivation” (Helen, Humanities and Education student). It appeared that enhancing interest and motivation was mainly dependent on the students’ own efforts to succeed in their course of study and thus to generate favorable analytics data. However, some students (n = 7) felt that it could be additionally enhanced by diversifying and improving the analytics tools in the LAD. For example, the opportunities for more detailed analyses and future study planning or comparisons of study performance with that of peers might further increase these students’ motivation and interest in their studies. Even so, it was also considered possible that especially comparisons between students might have the opposite, demotivating and discouraging effect.

All students (n = 16) mentioned that using the LAD facilitated the process of seeking and accessing help. It enabled the identification of potential support needs—for instance, if several courses were failed or left unfinished. As noted, they were perceived as alarming signals for the students themselves to seek help and for the guidance personnel to provide targeted support. As one of the students emphasized, it was important that not only ‟a teacher [tutor] gets interested in looking at what the situation is but also that a student would understand to communicate regarding the promotion of studies and situations” (Emily, Social Services and Health Care student). Some students (n = 9) suggested that the students, tutor teachers, or both could receive automated alerts if concerns were to arise. On the other hand, the impact of such automated notifications on changing the course of study was considered somewhat questionable. Above all, the students (n = 16) preferred human contact and personal support by the guidance personnel, who would use a sensitive approach to address possibly delicate issues. Support would be important to include in existing practices, as the tutor teachers should not be overburdened. One of the students also stated that the automated alerts could be sufficient if they just worked effectively.

4.3 LAD as a part of the reflection phase and processes

The students addressed the use of the LAD and its development as a part of the reflection phase processes of SRL through categories outlined in Table 3.

The students widely appreciated the support provided by the use of the LAD for the process of evaluation and reflection. The majority (n = 15) mentioned that it allowed them to individually reflect on the underlying aspects of their study performance, such as what kind of learners they are, what type of teaching or learning methods suit them, and what factors impact their learning. Similarly, the students (n = 16) valued the possibility of examining the analytics data together with the guidance personnel, such as tutor teachers, and commonly expressed a desire to revisit the LAD in future guidance meetings. It was thought to promote the interpretation of analytics data and to facilitate collective reflection on the reasons behind one’s study success or failure. However, this might require a certain orientation from the guidance personnel, as the student describes below:

I feel that it’s possible to address such themes that what may perhaps cause this. Of course, a lot depends on how amenable the teacher [tutor] is, like are we focusing on how the studies are going but in a way, not so much on what may cause it. (Sophia, Humanities and Education student)

Some students (n = 8) proposed incorporating familiarization with analytics insights into course implementations of the degree programs. Additionally, many students (n = 11) expressed a desire to examine the student group’s general progress in tutoring classes together with the tutor teacher and peers, particularly if the results were properly targeted and anonymized, and presented in a discreet manner. However, some students (n = 5) found this irrelevant. The students were generally wary to evaluate and compare an individual student’s study performance in relation to the peer average through the LAD. While some students (n = 4) welcomed such an opportunity, others (n = 6) considered it unnecessary. A few students (n = 5) emphasized that such comparisons between students should be optional and visible if desired, and one student (n = 1) did not have a definite view about it. Rather than competing with others, the students stressed the importance of challenging themselves and evaluating study performance against their own goals or previous achievements.

According to the students (n = 16), the use of the LAD was associated with a wide range of affective reactions. Positive responses such as joy, relief, and satisfaction were considered to emerge if the analytics data displayed by the LAD was perceived as favorable and expected, and supportive of future learning. Similarly, negative responses such as anxiety, pressure, or stress were likely to occur if such data indicated poor performance, thus challenging the learning process. On the other hand, such self-reactions could also appear as neutral or indifferent, depending on the student and the situation. Individual responses were related not only to the current version of the LAD but also to its further development targets. Some students (n = 3) pointed out the importance of guidance and support, through which the affective reactions could be processed together with professionals. As one of the students underlined, it is important “that there is also that support for the studies, that it isn’t just like you have this chart, and it looks bad, that try to manage. Perhaps there is that support, support in a significant role as well” (Sophia, Humanities and Education student). It seemed critical that the students were not left alone with the LAD but rather were given assistance to deal with the various responses its use may elicit.

4.4 Summary of findings on LAD utilization to promote SRL among HE students

In summary, HE students’ perceptions on the utilization of an LAD to promote SRL phases and processes were largely congruent, but nonetheless partly varied. In particular, the students agreed on the support provided by the LAD during the performance phase and for the purpose of metacognitive monitoring. Such activity was thought to not only enable the students to observe their studies and learning, but to also create the basis for the emergence of all other processes, which were facilitated by the monitoring. That is, while the students familiarized themselves with the course of their studies via the analytics data, they could further apply these insights—for instance, to visualize study situations, enhance motivation, and identify possible support needs. Monitoring with the LAD was also perceived to partly promote the students to the forethought and reflection phases and processes by giving them grounds to target their development areas as well as to reflect on their studies and learning individually and jointly with their tutor teachers. However, it was clear that less emphasis was placed on using the LAD for study planning, addressing individual interests, activating self-efficacy, and supporting environmental structuring, thus giving incentives for their further investigation and future improvement.

Although the LAD used in this study seemed to serve many functions as such, its holistic development was deemed necessary for more thorough SRL support. In particular, the students agreed on the need to improve such an analytics application to further strengthen the performance phase processes—particularly monitoring—by, for instance, developing it for the students’ independent use, and by integrating it with instructional and guidance practices provided by their educators. Moreover, the students commonly wished for more advanced analytics tools that could more directly contribute to the planning of studies and joint reflection of group-level analytics data. To better support the various processes of SRL, new features were generally welcomed into the LAD, although the students’ views and emphases on them also varied. Mixed perspectives were related, for instance, to the need to enrich data or compare students within the LAD. Thus, it seemed important to develop the LAD to conform to the preferences of its users. Along with improving the LAD, students also paid attention to the development of pedagogical practices and guidance processes that together could create appropriate conditions for the emergence of SRL.

5 Discussion

The purpose of this study was to gain insights into HE students’ perceptions on the utilization of an LAD to promote their SRL. The investigation extended the previous research by offering in-depth descriptions of the specific phases and processes of SRL associated with the use of an LAD and its development targets. By applying a study path perspective, it also provided novel insights into how to promote students to become self-regulated learners and effective users of analytics data as an integral part of their studies in HE.

The students’ perspectives on the use of LAD and its development were initially explored as a part of the forethought phase processes of SRL, with a particular focus on the planning and directing of studies and learning. In line with previous research (e.g., Divjak et al., 2023; Schumacher & Ifenthaler, 2018; Silvola et al., 2023), the students in this study appreciated an analytics application that helped them prepare for their future learning endeavors—that is, the initial phase of the SRL cycle (see Zimmerman & Moylan, 2009). Using the LAD specifically allowed the students to recognize their development areas and offered a basis to organize their future coursework. However, improvements to allow students to set individual goals and make plans directly within the LAD, as well as to increase awareness of general degree goals, were also desired. These seem to be pertinent avenues for development, as goals may inspire the students not only to invest greater efforts in learning but also to track their achievements against these goals (Wise, 2014; Wise et al., 2016). While education is typically entered with individual starting points, it is important to allow the students to set personal targets and routes for their learning (Wise, 2014; Wise et al., 2016).

The results of this study indicate that the use of LADs is primarily driven and shaped by students’ personal interests and preferences, which commonly play a crucial role in the development of SRL (see Zimmerman & Moylan, 2009; Panadero & Alonso-Tapia, 2014). It might particularly benefit those students for whom analytics-related activities are characteristic and of interest, and who consider them personally meaningful for their studies. It has been argued that if students consider analytics applications serve their learning, they are also willing to use them (Schumacher & Ifenthaler, 2018; Wise et al., 2016). On the other hand, it has also been stated that not all students are necessarily able to maximize its possible benefits on their own and might need support in understanding its purpose (Wise, 2014) and in finding personal relevance for its use. The findings of this study suggest that a more individual fit of LADs could be promoted by allowing students to customize its functionalities and displays. Comparable results have also been obtained from other studies (e.g., Bennett, 2018; Rets et al., 2021; Roberts et al., 2017; Schumacher & Ifenthaler, 2018), thus highlighting the need to develop customized LADs that better meet the needs of diverse students and that empower them to control their analytics data. More attention may also be needed to promote the use and development of LADs to support self-efficacy, as it appeared to be an unrecognized potential still for many students in this study. According to Rets et al. (2021), using LADs for such a purpose might particularly benefit online learners and part-time students, who often face various requirements and thus may forget the efforts put into learning and giving themselves enough credit. By facilitating students’ self-confidence, it could also promote the necessary changes in study behavior, at least for those students with low self-efficacy (Rets et al., 2021).

Second, the students’ views on the use of the LAD and its development were investigated in terms of the performance phase processes of SRL, with an emphasis on the control and observation of studies and learning. In line with the results of other studies (De Barba et al., 2022; Rets et al., 2021; Schumacher & Ifenthaler, 2018; Silvola et al., 2023), the students preferred using the LAD to monitor their study performance—they wanted to follow their progress and success over time and keep themselves and their educators up to date. According to Jivet et al. (2017), such functionality directly promotes the performance phase of SRL. Moreover, it seemed to serve as a basis for other activities under SRL, all of which were heavily dependent and built on the monitoring. The results of this study, however, imply that monitoring opportunities should be further expanded to provide even more detailed insights. Moreover, they indicate the need to develop and refine pedagogical practices at the organizational level in order to better serve student monitoring. As monitoring plays a crucial role in SRL (Zimmerman & Moylan, 2009), it is essential to examine how it is related to other SRL processes and how it can be effectively promoted with analytics applications (Viberg et al., 2020).

In this study, the students used the LAD not only to monitor but also to image and visualize their learning. In accordance with the views of Papamitsiou and Economides (2015), the visualizations transformed the analytics data into an easily interpretable visual form. The visualizations were not considered to generate information overload, although such a concern has sometimes been associated with the use of LADs (e.g., Susnjak et al., 2022). However, the students widely preferred even more descriptive and nuanced illustrations to clarify and structure the analytics data. At the same time, care must be taken to ensure that the visualizations do not divert too much attention from other relevant aspects of learning, as was also found important in prior research (e.g., Charleer et al., 2018; Wise, 2014). It seems critical that an LAD inform but not overwhelm its users (Susnjak et al., 2022). As argued by Klein et al. (2019), confusing visualizations may not only generate mistrust but also lead to their complete nonuse.

Although the LAD piloted in the study was considered to be a relatively functional application, it could be even more accessible and usable if it was incorporated into the student information system and enriched with the data from it. Even then, however, the LAD should remain simple to use and its data privacy ensured. It has been argued that more information is not always better (Aguilar, 2018), and the analytics indicators must be carefully considered to truly optimize learning (Clow, 2013). While developing their SRL, students would particularly benefit from a well-structured environment with fewer distractions and more facilitators for learning (Panadero & Alonso-Tapia, 2014). The smooth promotion of studies also seems to require personal access to the analytics data. Similar to the learners in Charleer and colleagues’ (2018) study, the students in this study desired to take advantage of the LAD autonomously, beyond the guidance context. It was believed to be especially used when they were actively promoting their studies. This is seen as a somewhat expected finding given the significant role of study performance indicators in the LAD. However, the question is also raised as to whether such an analytics application would be used mainly by those students who progress diligently but would be ignored by those who advance only a little or not at all. Ideally, the LAD would serve students in different situations and at various stages of studies.

Using the LAD offered the students a promising means to enhance motivation and interest in their studies through the monitoring of analytics data. However, not all students were inspired in the same manner or similar analytics data displayed by the LAD. Although the LAD was seen as inspiring and interesting in many ways, it also had the potential to demotivate or even discourage. This finding corroborates the results of other studies reporting mixed results on the power of LADs to motivate students (e.g., Bennett, 2018; Corrin & de Barba, 2014; Schumacher & Ifenthaler, 2018). As such, it would be essential that the analytics applications consider and address students with different performance levels and motivational factors (Jivet et al., 2017). Based on the results of this study, diversifying the tools included in the LAD might also be necessary. On the other hand, the enhancement of motivation was also found to be the responsibility of the students themselves—that is, if the students wish the analytics application to display favorable analytics data and thus motivate them, they must first display concomitant effort in their studies.

The use of the LAD provided a convenient way to intervene if the students’ study performance did not meet expectations. With the LAD, both the students and their tutor teachers could detect signs of possible support needs and address them with guidance. In the future, such needs could also be reported through automated alerts. Overall, however, the students in this study preferred human contact and personal support over automated interventions, contrary to the findings obtained by Roberts and colleagues (2017). Being identified to their educators did not seem to be a particular concern for them, although it has been found to worry students in other contexts (e.g., Roberts et al., 2017). Rather, the students felt they would benefit more from personal support that was specifically targeted to them and sensitive in its approach. The students generally demanded delicate, ethical consideration when acting upon analytics data and in the provision of support, which was also found to be important in prior research (e.g., Kleimola & Leppisaari, 2022). Additionally, Wise and colleagues (2016) underlined the need to foster student agency and to prevent students from becoming overly reliant on analytics-based interventions: if all of the students’ mistakes are pointed out to them, they may no longer learn to recognize mistakes on their own. Therefore, to support SRL, it is essential to know when to intervene and when to let students solve challenges independently (Kramarski & Michalsky, 2009).

Lastly, the students’ perceptions on the use and development of the LAD were examined from the perspective of the reflection phase processes of SRL, with particular attention given to evaluation and reflection on studies and learning. The use of the LAD provided the students with a basis to individually reflect on the potential causes behind their study performance, for better or worse. Moreover, they could address such issues together with guidance personnel and thus make better sense of the analytics data. Corresponding to the results of Charleer et al.’s (2018) study, collective reflection on analytical data provided the students with new insights and supported their understanding. Engaging in such reflective practices offered the students the opportunity to complete the SRL cycle and draw the necessary conclusions regarding their performance for subsequent actions (see Zimmerman & Moylan, 2009). In the future, analytics-based reflection could also be implemented in joint tutoring classes and courses included in the degree programs. This would likely promote the integration of LADs into the activity flow of educational environments, as recommended by Wise and colleagues (2016). In sum, using LADs should be a regular part of pedagogical practices and learning processes (Wise et al., 2016).

When evaluating and reflecting on their studies and learning, the students preferred to focus on themselves and their own development as learners. Similar to earlier findings (e.g., Divjak et al., 2023; Rets et al., 2021; Roberts et al., 2017; Schumacher & Ifenthaler, 2018), the students felt differently about the need to develop LADs to compare their study performance with that of other students. Although this function could help some of the students to position themselves in relation to their peers, others thought it should be optional or completely avoided. In agreement with the findings of Divjak et al. (2023), it seemed that the students wanted to avoid mutual competition comparisons; however, it might not be harmful for everyone and in every case. Consequently, care is required when considering the kind of features in the LAD that offer real value to students in a particular context (Divjak et al., 2023). Rather than limiting the point of reference only to peers, it might be useful to also offer students other targets for comparative activity, such as individual students’ previous progress or goals set for the activity (Wise, 2014; Wise et al., 2016; see also Bandura, 1986). In addition, it is important that students not be left alone to face and cope with the various reactions that may be elicited by such evaluation and reflection with analytics data (Kleimola & Leppisaari, 2022). As the results of this study and those of others (e.g., Bennett, 2018; Lim et al., 2021) generally indicate, affective responses evoked by LADs may vary and are not always exclusively positive. Providing a safe environment for students to reflect on successes and failures and to process the resulting responses might not only encourage necessary changes in future studies but also promote the use of an LAD as a learning support.

In summary, the results of this study imply that making an effective use of an analytics application—even with a limited amount of analytics data and functionality available—may facilitate the growth of students into self-regulated learners. That is, even if the LAD principally addresses some particular phase or process of SRL, it can act as a catalyst to encourage students in the development of SRL on a wider scale. This finding also emphasizes the interdependent and interactive nature of SRL (see Zimmerman, 2011; Zimmerman & Moylan, 2009) that similarly seems to characterize the use of an LAD. However, the potential of LADs to promote SRL may be lost unless students themselves are (pro)active in initiating and engaging with such activity or receive appropriate pedagogical support for it. There appears to be a specific need for guidance that is sensitive to the students’ affective reactions and would help students learn and develop with analytics data. Providing the students with adequate support is particularly critical if their studies have not progressed favorably or as planned. It seems important that the LAD would not only target those students who are already self-regulated learners but, with appropriate support and guidance, would also serve those students who are gradually growing in that direction.

5.1 Limitations and further research

This study has some limitations. First, it involved a relatively small number of HE students who were examined in a pilot setting. Although the sample was sufficient to provide in-depth insights and the saturation point was reached, it might be useful in further research to use quantitative approaches and diverse groups of students to improve the generalizability of results to a larger student population. Also, addressing the perspectives of guidance personnel, specifically tutor teachers, could provide additional insights into the use and development of LADs to promote SRL.

Second, the LAD piloted and investigated in this study was not yet widely in use or accessible by the students. Moreover, it was examined for a relatively brief time, so the students’ perceptions were shaped not only by their experiences but also by their expectations of its potential. Future research on students and tutor teachers with more extensive user experience could build an even more profound picture of the possibilities and limitations of the LAD from a study path perspective. Such investigation might also benefit from trace data collected from the students’ and tutor teachers’ interactions with the LAD. It would be valuable to examine how the students and tutor teachers make use of the LAD in the long term and how it is integrated into learning activities and pedagogical practices.

Third, due to the emphasis on an HE institution and the analytics application used in this specific context, the transferability of results may be limited. However, the results of this study offer many important and applicable perspectives to consider in various educational environments where LADs are implemented and aimed at supporting students across their studies.

6 Conclusions

The results of this study offer useful insights for the creation of LADs that are closely related to the theoretical aspects of learning and that meet the particular needs of their users. In particular, the study increases the understanding of how such analytics applications should be connected to the entirety of studies—that is, what kind of learning processes and pedagogical support are needed alongside them to best serve students in their learning. Consequently, it encourages a comprehensive consideration and promotion of pedagogy, educational technology, and related practices in HE. The role of LA in supporting learning and guidance seems significant, so investments must be made in its appropriate use and development. In particular, the voice of the students must be listened to, as it promotes their commitment to the joint development process and fosters the productive use of analytics applications in learning. At its best, LA becomes an integral part of HE settings, one that helps students to complete their studies and contributes to their development into self-regulated learners.

Data availability

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- HE:

-

Higher education

- LA:

-

Learning analytics

- LAD:

-

Learning analytics dashboard

- RQ:

-

Research question

- SRL:

-

Self-regulated learning

References

Aguilar, S. J. (2018). Examining the relationship between comparative and self-focused academic data visualizations in at-risk college students’ academic motivation. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 50(1), 84–103. https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2017.1401498

Anthonysamy, L., Koo, A-C., & Hew, S-H. (2020). Self-regulated learning strategies and non-academic outcomes in higher education blended learning environments: A one decade review. Education and Information Technologies, 25(5), 3677–3704. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-020-10134-2

Azevedo, R., Guthrie, J. T., & Seibert, D. (2004). The role of self-regulated learning in fostering students’ conceptual understanding of complex systems with hypermedia. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 30(1–2), 87–111. https://doi.org/10.2190/DVWX-GM1T-6THQ-5WC7

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice-Hall.

Barnard-Brak, L., Paton, V. O., & Lan, W. Y. (2010). Profiles in self-regulated learning in the online learning environment. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 11(1), 61–80. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v11i1.769

Beheshitha, S. S., Hatala, M., Gašević, D., & Joksimović, S. (2016). The role of achievement goal orientations when studying effect of learning analytics visualizations. Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Learning Analytics and Knowledge (pp. 54–63). Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/2883851.2883904

Bennett, E. (2018). Students’ learning responses to receiving dashboard data: Research report. Huddersfield Centre for Research in Education and Society, University of Huddersfield.

Bodily, R., & Verbert, K. (2017). Review of research on student-facing learning analytics dashboards and educational recommender systems. IEEE Transactions on Learning Technologies, 10(4), 405–418. https://doi.org/10.1109/TLT.2017.2740172

Broadbent, J., & Poon, W. L. (2015). Self-regulated learning strategies & academic achievement in online higher education learning environments: A systematic review. The Internet and Higher Education, 27, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2015.04.007

Callan, G., Longhurst, D., Shim, S., & Ariotti, A. (2022). Identifying and predicting teachers’ use of practices that support SRL. Psychology in the Schools, 59(11), 2327–2344. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22712

Charleer, S., Moere, A. V., Klerkx, J., Verbert, K., & De Laet, T. (2018). Learning analytics dashboards to support adviser-student dialogue. IEEE Transactions on Learning Technologies, 11(3), 389–399. https://doi.org/10.1109/TLT.2017.2720670

Chenail, R. J. (2011). Interviewing the investigator: Strategies for addressing instrumentation and researcher bias concerns in qualitative research. The Qualitative Report, 16(1), 255–262. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2011.1051

Clow, D. (2013). An overview of learning analytics. Teaching in Higher Education, 18(6), 683–695. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2013.827653

Conole, G., Gašević, D., Long, P., & Siemens, G. (2011). Message from the LAK 2011 general & program chairs. Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Learning Analytics and Knowledge. Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/2090116

Corrin, L., & De Barba, P. (2014). Exploring students’ interpretation of feedback delivered through learning analytics dashboards. In B. Hegarty, J. McDonald, & S-K. Loke (Eds.), ASCILITE 2014 conference proceedings—Rhetoric and reality: Critical perspectives on educational technology (pp. 629–633). Australasian Society for Computers in Learning in Tertiary Education (ASCILITE). https://www.ascilite.org/conferences/dunedin2014/files/concisepapers/223-Corrin.pdf

Costas-Jauregui, V., Oyelere, S. S., Caussin-Torrez, B., Barros-Gavilanes, G., Agbo, F. J., Toivonen, T., Motz, R., & Tenesaca, J. B. (2021). Descriptive analytics dashboard for an inclusive learning environment. 2021 IEEE Frontiers in Education Conference (FIE) (pp. 1–9). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/FIE49875.2021.9637388

De Barba, P., Oliveira, E. A., & Hu, X. (2022). Same graph, different data: A usability study of a student-facing dashboard based on self-regulated learning theory. In S. Wilson, N. Arthars, D. Wardak, P. Yeoman, E. Kalman, & D. Y. T. Liu (Eds.), ASCILITE 2022 conference proceedings: Reconnecting relationships through technology (Article e22168). Australasian Society for Computers in Learning in Tertiary Education (ASCILITE). https://doi.org/10.14742/apubs.2022.168

De Laet, T., Millecamp, M., Ortiz-Rojas, M., Jimenez, A., Maya, R., & Verbert, K. (2020). Adoption and impact of a learning analytics dashboard supporting the advisor: Student dialogue in a higher education institute in Latin America. British Journal of Educational Technology, 51(4), 1002–1018. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12962

Divjak, B., Svetec, B., & Horvat, D. (2023). Learning analytics dashboards: What do students actually ask for? Proceedings of the 13th International Learning Analytics and Knowledge Conference (pp. 44–56). Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/3576050.3576141

Dollinger, M., & Lodge, J. M. (2018). Co-creation strategies for learning analytics. Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Learning Analytics and Knowledge (pp. 97–101). Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/3170358.3170372

Eickholt, J., Weible, J. L., & Teasley, S. D. (2022). Student-facing learning analytics dashboard: Profiles of student use. IEEE Frontiers in Education Conference (FIE) (1–9). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/FIE56618.2022.9962531

Elo, S., & Kyngäs, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(1), 107–115. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x

Elouazizi, N. (2014). Critical factors in data governance for learning analytics. Journal of Learning Analytics, 1(3), 211–222. https://doi.org/10.18608/jla.2014.13.25

Heikkinen, S., Saqr, M., Malmberg, J., & Tedre, M. (2022). Supporting self-regulated learning with learning analytics interventions: A systematic literature review. Education and Information Technologies, 28(3), 3059–3088. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-022-11281-4

Jivet, I., Scheffel, M., Drachsler, H., & Specht, M. (2017). Awareness is not enough: Pitfalls of learning analytics dashboards in the educational practice. In É. Lavoué, H. Drachsler, K. Verbert, J. Broisin, & M. Pérez-Sanagustín (Eds.), Lecture notes in computer science: Vol. 10474. Data driven approaches in digital education (pp. 82–96). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-66610-5_7

Jivet, I., Scheffel, M., Specht, M., & Drachsler, H. (2018). License to evaluate: Preparing learning analytics dashboards for educational practice. Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Learning Analytics and Knowledge (pp. 31–40). Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/3170358.3170421

Jivet, I., Scheffel, M., Schmitz, M., Robbers, S., Specht, M., & Drachsler, H. (2020). From students with love: An empirical study on learner goals, self-regulated learning and sense-making of learning analytics in higher education. The Internet and Higher Education, 47, 100758. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2020.100758

Jivet, I., Wong, J., Scheffel, M., Valle Torre, M., Specht, M., & Drachsler, H. (2021). Quantum of choice: How learners’ feedback monitoring decisions, goals and self-regulated learning skills are related. Proceedings of 11th International Conference on Learning Analytics and Knowledge (pp. 416–427). Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/3448139.3448179

Kim, J., Jo, I-H., & Park, Y. (2016). Effects of learning analytics dashboard: Analyzing the relations among dashboard utilization, satisfaction, and learning achievement. Asia Pacific Education Review, 17(1), 13–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-015-9403-8

Kleimola, R., & Leppisaari, I. (2022). Learning analytics to develop future competences in higher education: A case study. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 19(1), 17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-022-00318-w

Kleimola, R., López-Pernas, S., Väisänen, S., Saqr, M., Sointu, E., & Hirsto, L. (2023). Learning analytics to explore the motivational profiles of non-traditional practical nurse students: A mixed-methods approach. Empirical Research in Vocational Education and Training, 15(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40461-023-00150-0

Klein, C., Lester, J., Rangwala, H., & Johri, A. (2019). Technological barriers and incentives to learning analytics adoption in higher education: Insights from users. Journal of Computing in Higher Education, 31(3), 604–625. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12528-019-09210-5