Abstract

In recent years, social media such as YouTube, TikTok, and Instagram have become an essential part of the everyday lives of children and young adults. Integrating elements of these social media into higher education may have the potential to enhance situational intrinsic learning motivation through the emotional design and proximity to students' lives, but this also poses the risk of fostering a situational materialistic focus due to the ubiquitous materialistic content on especially Instagram, undermining situational intrinsic learning motivation. In the present study, we examined if the primary use of Instagram is associated with higher materialism and how exposure to Instagram-framed pictures influences situational intrinsic learning motivation. The current study conducted an online experiment. Participants (N = 148) were randomly assigned to one of three groups after they rated items about general and problematic social media use and materialism. In the first two groups, participants were asked to rate the pleasantness of luxury or nature Instagram-framed pictures. A third group received no pictures. Afterwards, the situational intrinsic learning motivation was assessed through a mock working task. The findings prove that people who (primarily) use Instagram tend to be more materialistic than people who (primarily) use another social medium and that exposure to Instagram-framed pictures neither positively nor negatively influenced situational intrinsic learning motivation but moderated the relationship between problematic social media use and situational intrinsic learning motivation. Limitations, implications, and future directions for social media use inhigher education are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Social media such as YouTube, TikTok, and Instagram have become essential and increasingly used in the everyday lives of adolescents and young adults over the past decade (Vaterlaus et al., 2016; We Are Social & Meltwater, 2023). The coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) and associated restrictions on social life regarding "social distancing" have led to a further increase in social media usage time and strengthened social media as a central meeting space (Brailovskaia & Margraf, 2021; Gao et al., 2020). With increased usage time, the risk of problematic social media use (PSMU) becomes more prevalent. A meta-analysis by Olson et al. (2022) found that problematic smartphone use (PSU) as well as problematic internet use (PIU), which both hold strong similarities to PSMU (Marino et al., 2021), have increased worldwide in recent years. One social medium that is particularly popular with adolescents and young adults is Instagram (We Are Social & Meltwater, 2023). Instagram is a photo-based platform that mainly relies on sharing aesthetic and filtered pictures. Even though social media platforms have become increasingly similar and use similar functions, each platform has unique characteristics and different motives for their use and can, therefore, be associated with specific consequences. The motives for using various social media show that Instagram is the most important platform for interaction with brand products (Pelletier et al., 2020). Therefore, content that emphasizes materialism is more present on Instagram than on other social media platforms. Twenge and Kasser (2013) showed that materialism has increased over the past several decades. According to Kasser et al. (2004), one possible reason for this increase in materialism is the reception of media content that promotes materialism. Besides the influence of materialism on negative consumption behaviors (Pellegrino et al., 2022), researchers have also examined the consequences of materialism on learning and achievement variables, demonstrating that adolescents and students who are highly materialistic have lower grades and academic engagement compared to less materialistic adolescents and students (Goldberg et al., 2003; King, 2020). Materialism is also associated with reduced intrinsic learning motivation (ILM; Ku et al., 2012, 2014; Vansteenkiste et al., 2005). ILM is defined as learning for inherent interest or enjoyment, distinguishing it from extrinsic learning motivation (ELM), where learning incentives are external (Ryan & Deci, 2020). Remarkably, Ku et al. (2014) also demonstrated that merely the priming of materialism leads to reduced use of intrinsic learning strategies.

Findings on the relationship between PIU and ILM have shown a slight tendency toward a negative relationship (Reed & Reay, 2015; Truzoli et al., 2020). On the other hand, studies have shown that using social media in an educational context increases students' ILM (Gulzar et al., 2022; Rasheed et al., 2020; Samuels-Peretz et al., 2017). However, studies examining the influence of elements of popular social media platforms, such as Instagram posts, on ILM in an educational context are still rare. The integration of such an element can promote ILM due to its proximity to the students' living environment or reduce ILM as students may associate Instagram with materialism, which should be avoided at all costs, as ILM is one of the critical predictors of academic performance (Hendijani et al., 2016; Murayama et al., 2013; Vansteenkiste et al., 2005). The present study aims to fill that gap in research and attempts to find out whether materialism varies depending on the primary social media platform used and, in addition, whether the integration of elements of the popular social media platform Instagram has an influence on ILM.

2 Theoretical background

2.1 Social media and problematic social media use

Social media is an umbrella term for all applications that enable people to access all kinds of information through digital space (Schmidt & Taddicken, 2017). Social media platforms represent an important subgroup of social media. Three types of social media platforms can be distinguished based on different types of content: Social networking platforms (e.g. Facebook) are primarily used for building or maintaining a social network. Discussion platforms (e.g. Twitter) focus on discussing a particular topic or exchanging information. Furthermore, user-generated content (UGC) platforms focus mainly on publishing or consuming content, usually pictures or videos, created by users (Schmidt & Taddicken, 2017). UGC platforms like YouTube, TikTok, Instagram, and Snapchat are viral among adolescents and young adults (Auxier & Anderson, 2021; Feierabend et al., 2021; We Are Social & Meltwater, 2023). In social media use, the randomness and unpredictability of rewarding events (e.g. exciting story after three boring ones) are central in triggering problematic use since anticipating such rewards already triggers a feeling of pleasure (Griffiths, 2018). In this context, psychologists also speak of intermittent reinforcement, which has been identified as a central mechanism for developing and maintaining addiction disorders such as pathological gambling (Griffiths & Nuyens, 2017).

PSMU can be defined as addiction-like behavior, which includes the nine criteria for internet gaming disorder of DSM V, namely preoccupation, withdrawal, persistence, tolerance, displacement, problem, deception, escape, and conflict (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; van den Eijnden et al., 2016). Persons with PSMU postpone planned activities for using social media (displacement) or try to spend less time on social media but fail (persistence). Several studies have shown that the use of Instagram is associated with more PSMU or PSU compared to the use of other social media raising concerns and increasing the need for research about Instagram use (Limniou et al., 2022; Marengo et al., 2022; Rozgonjuk et al., 2018). However, it has to be mentioned that PSMU is not an official clinical diagnosis in the relevant classification systems and that the debate regarding terminology is still ongoing. Panova and Carbonell (2018, p. 256) argued that using the term addiction in terms of smartphone behavior is problematic due to “the vague definitions of the criteria for smartphone addiction and the lack of severe psychological and physical consequences associated with it”. Thus, we use the term PSMU for the current paper, as proposed in Panova and Carbonell (2018), instead of social media addiction. In line with Rozgonjuk et al. (2020), we speak of individual tendencies toward PSMU in our sample to emphasize that PSMU is not clinically relevant.

2.2 Social media use und materialism

The concept of materialism originated in philosophy and referred to the idea that reality is composed solely of matter (Lange, 1925). In most empirical research over the past several years, however, materialism is understood as a series of values in which a person achieves success and happiness through money and material possessions (Richins & Dawson, 1992). Accordingly, for materialists, a person is considered successful only if, for example, he or she owns an expensive luxury watch or car. Kasser et al. (2004) cite social modeling as a cause for the development of materialism, stating that people tend to be more materialistic when exposed to messages in media that promote materialism. In social media such as YouTube, Instagram, and TikTok, it has become a common practice to display advertisements before playing videos or between different posts. In these advertisements, material possessions are often associated with positive emotions, such as happiness and joy, and are portrayed as essential goals in a person's life (Nairn & Opree, 2021). Several cross-sectional studies have demonstrated a positive relationship between materialism and increased watching of advertisements (Buijzen & Valkenburg, 2003; Jiang & Chia, 2009; Nairn & Opree, 2021; Rasmussen et al., 2022). In addition to advertisements, materialistic content like sharing the last purchases and exchanging information about brand products on social media is ubiquitous (Chu et al., 2013; Pellegrino et al., 2022). Empirical evidence for social modeling as a cause of developing materialism, as proposed by Kasser et al. (2004), can be derived from two longitudinal studies that show that frequent and prolonged exposure to materialistic content increases dispositional materialism in the long run (Chan et al., 2006; Opree et al., 2014).

A meta-analysis from Moldes and Ku (2020) shows that exposure to materialistic cues increases situational materialism, which the authors assume could manifest in higher materialism due to social modeling. Unlike advertisements on television, which can be bypassed by switching to another channel, in social media, advertisements are customized and firmly integrated into the newsfeed and stories function. Because of this, the influence of advertising in social media on materialism should be similar, if not higher, than the influence of television advertising. In fact, recent results from cross-sectional studies showed a positive relationship between social media use and materialism (Jameel et al., 2024; Ozimek et al., 2024; Thoumrungroje, 2018). However, one recent study could not find any relationship between social media use and materialism (Cleveland et al., 2023). The mixed results could be due to the social medium used, as none of the studies examined platform-specific effects on materialism, even though the focus on materialistic content differs between social media platforms. Regarding materialistic content, Instagram is worth mentioning. Instagram has been connected to the proliferation of glamorous and luxurious lifestyles (Marwick, 2015). Instagram is heavily focused on visual storytelling and is, therefore, successfully used by luxury fashion brands to promote their products (Deloitte, 2019; Natiqa et al., 2022). Tennille Kopiasz, former senior vice president of marketing for luxury perfume Dior, commented on Instagram as follows: "The best way for luxury brands to inspire consumers has always been through storytelling. As Instagram is a visual storytelling platform, the link is a natural fit." (Instagram, 2017, p. 5). Hence, people using (primarily) Instagram are confronted regularly and more often with pleasant pictures with materialistic content than people not using Instagram (primarily). Therefore, Instagram users who hold neutral attitudes to material goods could develop positive attitudes toward materialism due to the repeated and ubiquity presentation of material goods, known as the mere exposure effect (Zajonc, 1968). In addition, the presentation of material goods on Instagram from influencers or friends could serve as an upward comparison target in terms of social comparison theory (Festinger, 1954). As people always look happy in this kind of pictures, this may foster the motivation from Instagram users that someone needs to buy material goods to achieve "happiness". The assumption that the primary use of Instagram favors the development of materialism compared to the primary use of another social media platform appears conclusive. It is to be subjected to empirical testing.

2.3 Materialism and intrinsic learning motivation

Materialism, according to the consensus of most value researchers, is part of a dynamic circumplex value system in which it falls within the cluster of self-enhancement values such as power and hedonism and stands in conflict with collective values such as benevolence, family, and community (Burroughs & Rindfleisch, 2002; Schwartz, 1992). Grouzet et al. (2005) obtained similar results in their study, dividing the circumplex dynamic value system based on the two primary dimensions of intrinsic and extrinsic goals in terms of self-determination theory. The self-determination theory from Ryan and Deci (2000) postulates three basic needs whose satisfaction is central to motivation: autonomy, competence, and relatedness: Autonomy describes a sense of voluntariness, e.g. being able to act on one's initiative and responsibility. Competence describes the need to experience oneself as effective and impactful by successfully mastering tasks and being able to grow from them. The need for relatedness describes the need to feel a sense of belonging to a social environment, to be included in it, and to receive recognition from others. The salience of extrinsic goals of popularity and financial success, themselves closely associated with materialism, conflict with intrinsic goals of self-acceptance and self-direction (Grouzet et al., 2005). The frustration of basic needs seems likely for materialism, given the indicated conflicts with intrinsic life goals. Indeed, several studies showed that materialism was positively related to the frustration of all three basic needs, with frustration of autonomy, in particular, being the strongest (Chen et al., 2014; Dittmar et al., 2014; Kasser et al., 2014; Nagpaul & Pang, 2017; Tsang et al., 2014; Unanue et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2017). Hence, fulfilling the three basic psychological needs relates to ILM (Holzer et al., 2021; Reeve, 2002), this would imply that materialism is detrimental to ILM because it frustrates the three basic needs. Empirical evidence for this implication can be derived from the findings of Ku et al. (2012) and King and Datu (2017), as they could show that materialism was negatively related to intrinsic learning strategies such as mastery learning, positively related to amotivation and that materialism had a negative longitudinal effect on ILM, strengthening the assumption of a causal influence of materialism on ILM. As already mentioned Ku et al. (2014) showed that priming materialism reduces ILM. Similar findings emerged in a study by Vansteenkiste et al. (2005), in which students for whom intrinsic goals were emphasized in the work task showed better test performance, worked more intensively on the text, and engaged less superficially with the text than students for whom extrinsic goals such as financial benefit were emphasized in the work task. In one pilot study, we found a negative relationship between materialism and ILM (N = 116, r = .28, p = .002). It can be concluded that being materialistic or exposed to materialistic content undermines (situational) ILM.

On Instagram, extrinsic goals like popularity and financial success are emphasized. This emphasis on extrinsic goals could be adapted by its users, leading to cognitive processes of learning as a means to achieve material goods and welfare rather than for joy or personal growth, which may lead to a reduced ILM. Another possible motivational process explaining a reduced ILM for Instagram users is the highly favorable cost-benefit ratio (Aru & Rozgonjuk, 2022). In exchange for almost no cognitive effort, Instagram provides instant gratification due to its visual attraction and positive emotion hindering people’s ability to sustain prolonged effort, which is necessary for ILM (Pekrun et al., 2010).

As we expect a relationship between Instagram use and materialism and empirical evidence showing a negative relationship between materialism and ILM, the assumption that the primary use of Instagram reduces ILM compared to the primary use of another social media platform appears conclusive. It is to be subjected to empirical testing.

2.4 Instagram use in higher education

Using social media in an educational context positively affects students' engagement, ILM, and creativity (Gulzar et al., 2022; Malik et al., 2020; Samuels-Peretz et al., 2017). Gulzar et al. (2022) and Malik et al. (2020) showed that the cognitive use of social media (creating and sharing content) in academic activities increased ILM and, as a result, engagement and creativity. Samuels-Peretz et al. (2017) showed that integrating individual elements of Facebook (e.g. a fan page) or YouTube (e.g. introductory videos for general concepts) into academic courses promoted students' deep learning strategies (e.g. reflective learning). In addition, most young adults indicated that work assignments incorporating social media tools increased their engagement and enjoyment, a central concept in ILM, compared to traditional assignments (Samuel-Peretz et al., 2017). In general, research on Instagram use in higher education is rare. The few studies that examined the effect of using Instagram in an educational context are primarily based on fostering language learning. Two studies showed that implementing Instagram in an English as a foreign language (EFL) writing class fostered student engagement and motivation (Min & Hashim, 2022; Prasetyawati & Ardi, 2020). Yet, the question about the enhancement of ILM due to the integration of elements of Instagram (e.g. Instagram-framed pictures) into the classroom, regardless of the subject, remains unclear because, to our knowledge, no study has examined the effect of Instagram-framed pictures on aspects of learning motivation, namely ILM.

Theoretical support for the hypothesis that integrating social media elements into the classroom could foster ILM comes from the cognitive, affective, and social theory of learning (CASTLE; Schneider et al., 2022). The CASTLE theory postulates that social cues in digital learning environments activate social schemata, which evoke social processes that foster motivational processes. The strength of the activation is due to the salience of the social cue (Schneider et al., 2022). In the CASTLE theory, digital media range from simple text-image combinations to dynamic and interactive media. An Instagram-framed picture is a simple text-image combination. Social cues such as an Instagram logo, which is highly salient due to the popularity of Instagram, could activate social schemata related to social integration or social relatedness, which may lead to social processes and a higher ILM. Another explanation due to the CASTLE theory is through emotional design, which can also function as a social cue (Schneider et al., 2022). Emotional design is defined as using visual design elements in multimedia learning material that facilitate learning by evoking positive emotions (Heidig et al., 2015). It has been shown that objective system qualities (e.g. visual aesthetic) in a digital learning environment can evoke positive emotion, which in turn fosters the motivation to use the digital learning material (Hassenzahl, 2004; Heidig et al., 2015; Tuch et al., 2010). One study by Heidig et al. (2015) showed that the perceived aesthetics (pleasantness) of a multimedia learning material evoked positive emotions (e.g. excitement) in the learners, which in turn fostered ILM, including continuing to work with the material. According to the logic of emotional design, positive emotions could be evoked through the exposure of Instagram-framed pictures due to their aesthetic character, which fosters ILM and the motivation to continue with the material. One last possible derivation of the CASTLE theory is that if learners are comfortable and familiar with digital learning material, which will be the case for Instagram for the vast majority of the students, they may be able to access the learning content more easily, concentrate better, and be more motivated (Schneider et al., 2022).

On the other hand, Instagram-framed pictures could evoke materialism due to the ubiquitous materialistic content on Instagram, which leads to a situational materialistic focus and, consequently, undermines situational ILM and the motivation to engage with the material more deeply. Several studies successfully showed that exposure to materialistic content through aesthetic pictures (e.g. luxury products) increases situational materialism (Ashikali & Dittmar, 2012; Bauer et al., 2012). As mentioned above, Ku et al. (2014) and Vansteenkiste et al. (2005) showed that exposure to materialistic cues decreases the use of intrinsic learning strategies, namely ILM. Overall, the assumption that exposure to Instagram-framed pictures promotes situational ILM seems only partially conclusive due to contradictory evidence. It will be subjected to empirical testing to clarify the relationship between exposure to Instagram-framed pictures and situational ILM.

2.5 Problematic social media use and intrinsic learning motivation

We use PSMU similar to PSU and PIU in the following due to strong conceptual similarities as social media is the main activity on the internet and smartphone (Marino et al., 2021). To the authors' knowledge, two studies have investigated the relationship between PIU and ILM. Reed and Reay (2015) showed that PIU has a significant independent negative impact, controlled for depressive and anxiety symptoms, on ILM, whereas Truzoli et al. (2020) merely demonstrated a non-significant negative relationship. In one pilot study, we found a negative relationship between social media use and ILM (N = 116, r = − .25, p = .004). In the following, we present two possible explanations for a negative relationship between PSMU and ILM, which are discussed in the literature.

2.5.1 Inattention

Aru and Rozgonjuk (2022) state that habitual smartphone use, mainly social media use, is associated with an inability to exert prolonged mental effort. The authors reason that the brain may perform a cost-benefit analysis and selects the activity with the best cost-benefit ratio. They further suggest that social media use takes precedence over cognitively demanding activities such as reading a book because the cost-benefit analysis is far more in favor of social media use. "Disruptive habitual use", as Aru and Rozgonjuk (2022) call it, leads to disrupted concentration on a smartphone-independent task due to opportunity costs. Several studies show that increased attention problems, such as a reduced ability to tune out unimportant stimuli or to be easily distracted or inattention, develop as a result of PSMU (Boer et al., 2020; Nikkelen et al., 2014; Xie et al., 2021). Attention problems, in turn, are negatively related to ILM, such as challenge-seeking, due to the necessity of attention to experience ILM (Pekrun et al., 2010).

2.5.2 Displacement hypothesis – factor of time

PSMU correlates positively with social media usage time (Boer et al., 2021; Marino et al., 2020). The more daily hours are spent on social media, the less time is available for other activities. This corresponds with the displacement hypothesis, which has been discussed to explain the negative consequences of television hours on reading skills (Ennemoser & Schneider, 2007). With the increased use of social media, there is less time left, which allows concentration to be directed solely to those goals that can be achieved in the time remaining. Applied to the context of learning, this would mean that intrinsic learning strategies (e.g. understanding something profoundly and engaging with it for a more extended time) would more likely have to give way to the goal of "memorizing to pass the exam", which reflects a surface learning approach, making ILM less likely. Consistent with the displacement hypothesis, Alt and Boniel-Nissim (2018) found that PIU was positively related to a surface learning approach. Similar results were found in a study in which increased PSU was associated with lower engagement in a deep approach to learning (Rozgonjuk et al., 2018). The less time available due to social media use, the more likely one is to focus on the learning strategies that can still be realized in time. Generalizing a surface learning strategy is more likely then. Consequently, deep learning strategies are undermined, and thus, ILM is lacking.

2.6 Current study

Several studies showed a positive relationship between social media use and materialism (Jameel et al., 2024; Ozimek et al., 2024; Thoumrungroje, 2018). This relationship may depend on the social medium used, as there are differences in the focus on materialistic content between social media platforms. The social media platform which is predestinated to promote materialism due to the concept of visual storytelling is Instagram. As a consequence, continuous and frequent exposure to materialistic content on Instagram should be more likely than on any other social media platform, which therefore manifests in higher materialism. Materialism stands in conflict with intrinsic goals and is associated with a lower ILM in adolescents and students (Ku et al., 2012, 2014; King & Datu, 2017). Hence, Instagram use could lead to lower ILM due to higher materialism. Due to the relationships described, it is hypothesized that the primary use of Instagram is associated with higher materialism (H1) and lower ILM (H2) compared to the primary use of other social media.

-

H1: Primary Instagram use is associated with higher materialism than primary use of other social media platform.

-

H2: Primary Instagram use is associated with lower ILM than primary use of other social media platform.

Instagram use in higher education enhances ILM (Min & Hashim, 2022; Prasetyawati & Ardi, 2020). In addition, derivations from the CASTLE (Schneider et al., 2022) support a positive influence of exposure to Instagram-framed pictures on situational ILM. By contrast, findings from studies that examined the exposure of materialistic content on situational materialism and ILM oppose to a positive influence from exposure to Instagram-framed pictures on situational ILM (Ashikali & Dittmar, 2012; Bauer et al., 2012; Ku et al., 2014; Vansteenkiste et al., 2005). Therefore, an undirected hypothesis was formulated that exposure to Instagram-framed pictures influences situational ILM.

-

H3:The exposure to Instagram-framed pictures influences situational ILM.

PSMU, due to the increased time spent on social media, increases the likelihood of facing materialistic content and using a surface-learning approach (displacement hypothesis), both undermining ILM (Alt & Boniel-Nissim, 2018; Ku et al., 2014). Another explanation for the negative impact of PSMU on ILM is due to the inherent "disruptive habitual use" in PSMU, which fosters symptoms of inattention and, therefore, decreases the ability to exert prolonged cognitive effort, which is necessary for ILM (Aru & Rozgonjuk, 2022; Boer et al., 2020; Pekrun et al., 2010; Xie et al., 2021). Several studies have shown that PSMU is more likely to occur if Instagram is primarily used compared to the use of any other social media platform (Limniou et al., 2022; Rozgonjuk et al., 2020). Thus, exposure to Instagram-framed pictures may influences the strength of the negative relationship between PSMU and situational ILM.

-

H4:Exposure to Instagram-framed pictures moderates the relationship between PSMU and situational ILM.

3 Method

3.1 Participants

A G*Power (Faul et al., 2009) a priori analysis for H1, H2, and H3 indicated that 128 participants (64 for each group) were required to achieve an intended power of 0.80, using a ANCOVA fixed model with 3 covariates (age, social media usage time and PSMU) with an expected medium effect size. For H4, a G*Power (Faul et al., 2009) a priori analysis indicated that 81 participants were required to achieve an intended power of 0.80, using a multiple linear regression fixed model with an expected medium effect size. We used the SurveyCircle online research platform to recruit survey participants (SurveyCircle, 2024). A total of N = 148 individuals from Germany participated in the study. We removed three data sets due to a failed attention check, resulting in an analysis sample of n = 145 participants (100 female, 44 male, and 1 diverse, Mage = 26.9, SDage = 6, age range: 18–46). The sample mainly consisted of undergraduate and graduate students (87.2%). As there were no differences neither in the dependent nor independent variables according to student status we did not control for student status in further analyses. None of the participants received any material compensation.Footnote 1

3.2 Material

We distinguished between two content types (luxury and nature pictures) to examine the possible effects of exposure to Instagram-framed pictures on situational learning motivation dependent on content. The Instagram-framed luxury pictures emphasized materialistic content, including luxury cars, mansions, jewelry, and money. The Instagram-framed nature pictures were designed to be neutral and included mainly animals and landscapes, thus indicating non-materialistic content, see Figure 1 for examples. We adopt the experimental design from previous studies, which examined the effect of exposure to materialistic content (luxury content pictures, dollar bill) compared to the exposure to non-materialistic content (nature content pictures) on situational materialism (Ashikali & Dittmar, 2012; Bauer et al., 2012; Caruso et al., 2013; Ku et al., 2014). A meta-analysis on priming materialism by Moldes and Ku (2020) confirmed that pictures depicting luxury products successfully prime materialism. Maio et al. (2009) stated with the so-called "bleed-over effect" that activating specific values through priming increases attitudes consistent with the activated value. In addition, activating specific values leads to the suppression of competing values that conflict with the activated value (seesaw effect). Related to the present study, this would mean that activating materialism through Instagram-framed luxury pictures rather than nature pictures would suppress non-materialistic values like intrinsic values and, in turn, ILM.

Forty-eight luxury and nature pictures were tested in two pilot studies with and without Instagram frames. The pictures emphasis on materialism was assessed following Ashikali and Dittmar (2012). The 13 highest-rated luxury pictures and the 13 lowest-rated nature pictures concerning materialism were selected for the present study. Using an Instagram frame increased the discrepancy between luxury and nature pictures about the perceived emphasis on materialism compared to no Instagram frame. To further ensure that the pictures differed only in their content, none of the luxury or nature pictures included people, hashtags, or the number of likes to avoid activating pre-existing attitudes. In addition, both content types were designed to be colorful and aesthetic to avoid differences in the perceived aesthetic (Heidig et al., 2015). The pictures were edited using the picture editing program "Gimp", unified to one size (320px width x 450px height), and integrated into a uniform Instagram frame. All pictures used are royalty-free and come from the websites "Pexels" and "Pixabay". In addition, following the recommendation of Kasser (2016), a control group was included in the design that was not presented with pictures to isolate the effects of Instagram-framed pictures on situational learning motivation.

3.3 Measures

3.3.1 Social media usage time and general usage of social media

The social media usage time was assessed based on one item ("On average, how many hours a day do you spend actively on UGC platforms?"). In addition, participants were asked to indicate which of the UGC platforms (TikTok, YouTube, Instagram, Snapchat, and Reddit) they use primarily and prefer most. Moreover, participants were asked how often they consume which formats (pictures, short videos, long videos, podcasts, and live videos) and content (entertainment, fashion, finance, gaming, general news, sport, and health) on these UGC platforms (1 "never" to 5 "very often").

3.3.2 Problematic social media use

PSMU was measured with the 9-item "Social Media Disorder Scale" (SMDS; van den Eijnden et al., 2016). We translated the original English version into German and used a translate-back-translate procedure to ensure the quality of the translations (Brislin, 1970). The nine items were slightly adjusted by replacing the word social media with UGC platforms. In line with some previous studies, a dichotomous response format was not used, as it was less the clinical diagnosis than the tendency of PSMU that was in the interest of the study (Marino et al., 2021; Savci et al., 2021; Yıldız Durak, 2020). The statements are worded as "During the past year, I..." followed by a sentence representative of a criterion (e.g. for escape, "I often used UGC platforms to escape from negative feelings"). Participants could indicate their approval level from 0 "strongly disagree" to 100 "strongly agree" by using a slider. Previous research demonstrates that the SMDS has acceptable external validity, internal consistency, and test-retest reliability for adolescents and students from Germany (Boer et al., 2020; Wartberg et al., 2020). For the present sample, Cronbach's α was 0.84 and construct reliability (CR; Fornell & Larcker, 1981; Cheung et al., 2023) was 0.88, both indicating good reliability (Hair et al., 2009).

3.3.3 Materialism

Materialism was assessed using the short version of the material value scale (MVS; Richins, 2004). We translated the original English version into German and used a translate-back-translate procedure (Brislin, 1970). A validated German translation of the MVS from Müller et al. (2013) showed only slight differences with our translation. The short version of MVS contains nine items, three items of which form each of the three subscales: success (e.g. "I like to own things that impress other people."), centrality (e.g. "I like a lot of luxury in my life."), and happiness (e.g. "My life would be better if I owned certain things that I do not have."). Participants indicated their agreement with the items using a slider (0 "strongly disagree" to 100 "strongly agree"). The short version of MVS was validated on adolescents and students and showed satisfactory construct and criterion validity (Richins, 2004). For the present sample, Cronbach's α was 0.80 and CR was 0.85 for the summed nine-item scale.

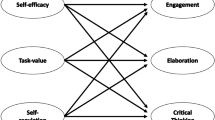

3.3.4 Situational learning motivation

Situational learning motivation was assessed using the fabricated items on text preference. Students rated items for their text preference, assuming that their response behavior would determine which text they would get to read on the following page. Enjoyment and challenge as facets of ILM were each assessed using three custom-created items following relevant literature (Guay et al., 2010; Middleton & Midgley, 1997; Yoon et al., 2015). An example item for enjoyment (ILM) is: "It is important to me that I enjoy reading the text."; and for challenge (ILM): "It is important to me that I am stimulated to think by reading the text.". In addition, three facets of ELM: comparison, money, and degree were exploratively surveyed with three items each as well (comparison: "It is important to me that I am more competent than others after reading the text.", money: "It is important to me that I get useful tips on how to handle money by reading the text.", and degree: "It is important to me that I find out how to perform better in future exam situations by reading the text."). Participants were asked to indicate their agreement with the above items using a slider (0 "strongly disagree" to 100 "strongly agree"). Cronbach's α ranged from 0.7–0.85 for the five facets in the present sample. CR ranged from 0.65–0.85 with only ELM comparison facet showing an unsatisfactory value being under 0.7. See Appendix Table 3 for all items.

3.4 Procedure

After agreeing to the data security conditions, participants participated in an online experiment designed with the survey tool "LimeSurvey" that took about 10 minutes to complete. First, participants were asked to refer only to UGC platforms in the following questions about their general social media use and PSMU. Before answering the questions participants were given a brief definition and examples of UGC platforms in advance to ensure knowledge of UGC platforms. Following this, participants completed a questionnaire on materialism. Participants were then randomly assigned to three groups: group one (G1), group two (G2) and group 3 (G3) by a random number generator from LimeSurvey. The chances of being assigned to one of the three groups were 33.33% for every participant. Participants in G1 (n = 51) were exposed to 13 Instagram-framed luxury pictures one by one and page by page and were asked to indicate how interesting and pleasant they found each of the pictures (1 "not at all" to 6 "entirely"). Participants in G2 (n = 49) were exposed to 13 Instagram-nature pictures and were asked to rate the pictures on the same scale as participants in G1. The order of the pictures in both groups was randomized. They were exposed to each picture for at least 10 seconds, as they could not click "next" before 10 seconds passed away. After rating the last picture, participants of G1 and G2 were asked to indicate on which platform the pictures just shown were "posted" as an attention check. Participants in G3 (n = 45) were not exposed to any pictures and were immediately directed to the next part of the online experiment. Following this, all participants received the mock instruction that they were presented with a text on the upcoming page that was selected based on their rating on items to text preference. They were given the following instructions:

"In the following part of the study, you will get a text you should read at your leisure. To select the appropriate text, we would first ask you to rate the following statements in terms of your agreement or disagreement. Based on your responses, the suitable text will be picked and presented on the next page."

Regardless of response behavior, no text was presented because text preference was the variable of interest used to indicate situational learning motivation. On the next page, all participants were educated about the deception and the research project. Finally, participants were instructed to provide information regarding gender, age, and student status. Figure 2 gives an overview of the online experiment procedure.

3.5 Ethical issues

On the page of the data security conditions, the participants were informed that their participation is anonymous and voluntary, that they could terminate the study at any time without facing any disadvantages, that no personal data within the meaning of the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) is collected and that their data is treated confidentially. The confidentiality of the data is secured as only the study's authors have access to the data, which is stored on a specially protected cloud provided by the Technical University of Braunschweig. The participants could only participate if they provided informed consent.

If they did not give consent, the study was terminated. There were no potential risks (e.g. psychological stress or exhaustion) for the participants at any time due to their participation. Transparency was secured as the participants were informed of the true objectives of the study immediately after the deception regarding the three different groups and the assessment of situational learning motivation. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Institute of Psychology at the Technical University of Braunschweig (FV_2022-06).

3.6 Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed using SPSS 28. After descriptive analysis, the relationship between the studied variables was first evaluated using bivariate correlations. For the expected relationships described in H1, H2 and H3, there are potential confounding variables as materialism decreases from adolescence to the age of 55 (Jaspers & Pieters, 2016) and is more prevalent in women (Segal & Podoshen, 2013). In addition, materialism may be associated with social media usage time and PSMU, as higher usage time leads to a greater probability of facing materialistic content. Therefore, a two-way ANCOVA was conducted to test H1, H2, and H3, including gender as a second factor due to its categorical nature and age, PSMU and social media usage time as covariates. Then, six moderation analyses, three with the dependent variable ILM (enjoyment) and three with the dependent variable ILM (challenge), were conducted to test H4 using Model 1 with the Process tool from Hayes (2018) in SPSS. The moderator (Instagram-framed pictures) was entered once as a comparison between luxury and nature Instagram-framed pictures, once as a comparison between luxury and no Instagram-framed pictures and as a comparison between nature and no Instagram-framed pictures. The independent variable in the analyses was PSMU. Materialism, age, gender, and social media usage time were also assessed as control variables. We did not control for socio-economic status (SES) as several studies have shown that SES has no or just small relation with PSMU (Paakkari et al., 2021; van Duin et al., 2021), materialism (Kim et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2020; Zhao et al., 2023) and ILM (McGeown et al., 2014). Due to possible interrelationships between variables we conducted exploratory factor analyses combining all items from materialism, problematic social media use, intrinsic learning motivation and extrinsic learning motivation and the single item of primarily used Instagram. The result of the varimax rotation showed that the items just loaded on the factors they were supposed to, indicating a good independence of the variables.

4 Results

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics and the bivariate correlations between the variables studied. The means and standard deviations of the variables of interest are consistent with values from past studies. It is noteworthy that PSMU was positively related to materialism (n = 145, r = .38, p < .01) and that the primary use of Instagram was also positively related to materialism (n = 143, r = .22, p < .01). For consumed formats, it was shown that a person who primarily uses Instagram consumes more pictures (M = 4.6, SD = .56) and fewer long videos (M = 2.58; SD = 1.02) than persons who use another social media platform primarily (pictures M = 3.28; SD = 1.32; long videos M = 3.72; SD = 1.04). Consuming fashion content differed between persons who primarily use Instagram (M = 2.78, SD = 1.3) and persons who use another social media platform primarily (M = 1.89, SD = 1.01). The differences remained stable when Instagram users were compared to non-Instagram users.

To test H1, a two-way ANCOVA was conducted. The prerequisites (variance homogeneity, covariates are independent from group effect and homogeneity of regression slopes) were met. A total of n = 142 individuals were included in the analysis, as three individuals were excluded from the analysis due to missing information on the primary social media platform used and gender. Of n = 142 individuals, 76 reported primarily using Instagram. Consistent with H1, the two-way ANCOVA result showed that individuals who primarily use Instagram are significantly more materialistic than those who primarily use another social medium (t (135) = -2.3, p = .02, r = .19) adjusting for age, gender, social media usage time and PSMU. Two two-way ANCOVA were conducted to test H2. In order to prevent priming effects from the depiction of luxury or nature pictures, only individuals from G3 were analyzed. This resulted in a total sample size of n = 44 included in the analysis. Of these 44 individuals, 21 reported primarily using Instagram. The results showed that individuals who primarily use Instagram did not differ significantly from individuals who primarily use another social medium regarding the expression of ILM (enjoyment) (t (37) = -1.59, p = .12, r = .24) and ILM (challenge) (t (37) = .37, p = .71, r = .06) adjusting for age, gender, social media usage time, PSMU and materialism. Therefore, H2 was rejected. To test H3, two two-way ANCOVAs were conducted. To examine the influence of Instagram-framed pictures on situational ILM (enjoyment), both Instagram-framing picture conditions (luxury and nature pictures) were compared with the control group (no pictures) regarding situational ILM. The results showed that situational ILM (enjoyment) neither differs in the comparison of luxury with no pictures (t (88) = − .10, p = .91, r = .01) nor in the comparison of nature with no pictures (t (85) = -1.2, p = .23, r = .12) adjusting for age, gender, social media usage time, PSMU and materialism. Therefore, H3 was rejected.

Table 2 shows the mean values of the three experimental groups regarding the expression of ILM (enjoyment) and ILM (challenge). In addition, the sample was classified into low and high PSMU using a median split. Individuals with low PSMU in G1 were less intrinsically motivated to learn (enjoyment) than individuals with low PSMU in G2 and G3. However, an opposite effect was found for individuals with a high PSMU in G1. These individuals were more intrinsically motivated to learn (enjoyment) than individuals with high PSMU in G2 and G3. No differences between the groups are shown for situational ILM (challenge).

Six moderation analyses were conducted to test H4 - three for each group comparison and two for each dependent variable ILM (enjoyment) and ILM (challenge). For situational ILM (enjoyment) and the group comparison (luxury vs. nature pictures), the result of the moderation analysis showed that 16.3 percent of the variance could be explained with the included variables (F = 3.69, p = .0045). Consistent with H4, Instagram-framed pictures moderated the relationship between PSMU and situational ILM (enjoyment); the interaction was significant (ß = − .68, t = -3.84, p = .001). For the group comparison (luxury vs. no pictures), it was also shown, consistent with H4, that the exposure to Instagram-framed pictures moderated the relationship between PSMU and situational ILM (enjoyment) (ß = − .47, t = -2.43, p = .017). The comparison (nature vs. no pictures) did not find any interactions. As can be seen in Fig. 3, individuals with higher PSMU in G1 (luxury pictures) expressed higher situational ILM (enjoyment) compared to the individuals in G2 (nature pictures) and G3 (no pictures). In particular, the combination of nature pictures and higher PSMU was associated with lower situational ILM (enjoyment). At the same time, individuals with lower PSMU in G1 showed lower situational ILM (enjoyment) than those in G2 and G3. The three moderation analyses for situational ILM (challenge) found no significant interactions. Therefore, H4 is partially supported.

5 Discussion

Social media are becoming increasingly important in the everyday lives of adolescents and young adults (Vaterlaus et al., 2016). Twenge and Kasser (2013) showed that materialism has increased over the past several years. Materialistic content is ubiquitous in social media, particularly on Instagram, which may cause the development of materialism due to social modeling described in Kasser et al. (2004). Due to the proximity to students' lives, elements of social media platforms (here, Instagram pictures) could foster situational ILM and make lectures in higher education more interesting if they are integrated into the courses. As ILM is one of the most significant predictors of academic performance, identifying predictors of materialism due to its undermining influence on ILM, and at the same time, how to use social media platforms in higher education to foster ILM, is of great interest (Hendijani et al., 2016; Murayama et al., 2013; Vansteenkiste et al., 2005). As far as the authors know, no study examined a social media platform-specific association with materialism. One study from Samuels-Peretz et al. (2017) showed that integrating individual elements of popular social media platforms into academic courses could foster deep learning strategies. The effect on situational ILM through the exposure of these elements was not examined. Therefore, the present study examined if materialism varies depending on the primarily used social media platform and if situational ILM is affected through the exposure of Instagram-framed pictures to produce evidence for or against integrating Instagram elements into higher educational settings. To this end, the present study makes three contributions.

First, the study identifies a platform-specific influence on materialism. People who primarily use Instagram tend to be more materialistic than people who primarily use another social medium. This relationship can be explained by the excessive presence of materialistic content on Instagram compared to other platforms. Instagram is built almost exclusively on aesthetic and filtered pictures. With the help of filters and aesthetic edits, pictures of luxury items appear even more spectacular and attract more attention to consumers through storytelling, which luxury brands use to advertise their products (Hootsuite, 2022). The focus on aesthetics and the presence of materialistic content on Instagram makes the development of materialism due to the primary use of Instagram a logical consequence due to the cited social modeling by Kasser et al. (2004). In addition, it would be interesting to know whether users also subjectively rated Instagram content more materialistically than other social media content. We found no differences in situational ILM between the primary use of Instagram and other social media platforms. The computed requirement for sample size was not met for H2, so the results should be evaluated with caution. Future studies should focus on primary Instagram use as a predictor of surface and deep learning approaches, as we found differences in the consumption of long videos, which may indicate a weakened attention span.

The findings about the platform-specific relationship between Instagram use and materialism also have theoretical implications for future research. Future studies examining social media use should consider that there are different motives for using (social) media, as the Users and Gratification Theory from Katz et al. (1973) has pointed out. Therefore, mixed results on the consequences of social media use summarizing several social media platforms could have been moderated by specific platform use, meaning that effects may have been overlooked. Therefore, future studies should consider measuring the primarily used social media platform with a single item or logged-on data from different social media platforms to uncover platform-specific moderation effects. For example, most recently, there is an uprising concern about the consequences of TikTok’s short video use as it has been shown that the use is negatively associated with academic delay of gratification, learning commitment, and attention (Chen et al., 2023; Xu et al., 2023; Ye et al., 2023). As research about social media and social media use is growing day by day, it is, therefore, worthy that future studies control for platform-specific effects.

Second, the study showed that exposure to Instagram-framed pictures, independent of the content, did not positively or negatively influence situational ILM. That also means that using Instagram-framed luxury pictures does not hurt the situational ILM, so the use of Instagram-framed luxury pictures should have no negative consequences, independent of the subject of the course. It may be that the priming (exposure to Instagram-framed pictures) did not work as intended, even though we adapted it from studies that tested it successfully (Ashikali & Dittmar, 2012; Bauer et al., 2012; Caruso et al., 2013).

We did not vary features like text, hashtags, or comments in the pictures due to the primary goal of a separate effect of the Instagram-framed picture itself. Future studies could connect the exposure to Instagram-framed pictures with a relevant working task and compare the working results with groups exposed to conventional text-format working tasks and other visual working task formats without Instagram-framed pictures. Studies could also vary the features of the Instagram-framed picture (hashtags or comment section) and examine if this variation makes it more realistic, which could make it more relevant to students due to the proximity of students' lives.

This contribution has practical implications. Several studies showed that materialism harms students' learning, school performance, and well-being (Goldberg et al., 2003; King & Datu, 2017; Ku et al., 2012, 2014; Moldes & Ku, 2020; Wang et al., 2017). It is, therefore, of interest to explore drivers of materialism for educators. We could provide evidence that the primary use of Instagram is positively associated with materialism compared to other social media's primary use. The use of Instagram material did not negatively influence situational ILM. Accordingly, educators could use Instagram pictures in a course to critically discuss the pursuit of material wealth promoted in social media and, based on this, determine the detrimental effects of materialism on students learning and well-being. In this context, educators could also reduce the emphasis on education as a means of making money and emphasize the intrinsic reward of learning, one of the main tasks of the education system, to promote personal growth (King & Datu, 2017). Future studies could research the effects of such courses with the help of Instagram pictures as an intervention, reducing materialism or fostering intrinsic values. In addition, future studies could expand our findings with the help of cognitive machine learning to predict human behavior after being exposed to Instagram-framed pictures showing humans in interaction with material luxury goods or nature through training neural networks (Parashar et al., 2023).

Third, the presented study identifies a moderator for the relationship between PSMU and situational ILM. Instagram-framed pictures moderate the relationship between PSMU and situational ILM (enjoyment). Individuals with high PSMU exhibited higher situational ILM (enjoyment) in G1 (luxury pictures) than individuals in G2 (nature pictures) or G3 (no pictures). At the same time, individuals with low PSMU in G1 showed lower situational ILM (enjoyment) than individuals in G2 and G3. At first glance, this seems counterintuitive, but it can be explained by the fact that the luxury Instagram-framed pictures rather trigger a feeling of pleasure in individuals with high PSMU because individuals with high PSMU also tend to be more favorable toward materialism and consequently enjoy viewing luxury pictures (Wang et al., 2020; Zawadzka et al., 2021). This favoritism was reflected in the fact that individuals in G1 with high PSMU found the luxury pictures more pleasant than individuals with low PSMU (t (49) = 1.4, p = .085). As a result of the experienced feeling of pleasure, it seems likely that individuals consequently indicate that it is essential to them that reading the text is enjoyable due to their situational feeling of pleasure. They also may assume, based on the previously shown luxury pictures with Instagram frames, that there could follow a text that is about social media. Another explanation could lie in the content of the pictures. The luxury pictures could evoke social context based on the Instagram frame, among other reasons, because the need for relatedness is satisfied through social media use (Karapanos et al., 2016; Lin, 2016; Sheldon et al., 2011). This evocation is especially likely for individuals with high PSMU, as they are more likely to satisfy their need for relatedness online (Kircaburun & Griffiths, 2018). Based on the CASTLE theory, one could also argue that Instagram-framed luxury pictures may be a stronger social cue in persons with high PSMU due to their proximity to general Instagram content.

6 Limitations

The presented study provides new insights and can be used as a springboard for future research on predictors of materialism and integrating elements of social media platforms in higher education, but it has several limitations. First, due to the study's cross-sectional design, no conclusions about cause-and-effect relationships can be made for the hypotheses and results. It is also possible that people high on materialism tend to use Instagram more than those low on materialism. We advocate a bidirectional, reinforcing relationship. Second, although social media usage time was not a primary variable in the current study, the exclusive use of self-report measures for social media usage time may be insufficient due to the only moderate correlation between logged and self-reported media use shown by the meta-analysis of Parry et al. (2021). Future studies should rely more on tracking or logging services to measure social media usage time because they are more accurate indicators than self-report measures. Third, although attention was paid to designing typical and aesthetical Instagram posts, we must consider that the Instagram-framed pictures may not have been seen as typical or believable posts by the viewers, which may have decreased the priming and use simulation effect of exposure. Future studies examining social media use via an experimental design should assess if the social media content (here, pictures) is typical for the participants. Fourth, ILM and ELM items were designed based on relevant literature. Despite satisfactory reliabilities, it must be considered that the items may not validly capture the respective facets of ILM and ELM. The additional use of established questionnaires on situational learning motivation would have strengthened the internal validity of the survey. Fifth, the sample consisted almost exclusively of students, so generalizing the findings is only possible to a limited extent. Particularly in the context of social media use, adolescence is of particular interest as an elementary developmental phase. In addition, cultural background should also be considered, as PSMU is more prevalent in collectivistic societies due to a "tighter" compliance to ingroup norms (using social media) in comparison to individualistic societies (Cheng et al., 2021). Therefore, future studies should expand their sample to include adolescents to be able to outline a developmental course of the consequences of Instagram use and control for cultural background of the adolescents. Sixth, an attempt was made to simulate an everyday situation in which individuals, depending on their problematic social media use and after consuming materialistic or neutral content, adjust their current learning motivation for an upcoming task. Since this is an online experiment, it cannot be ruled out that participants were distracted during the processing, despite several indications during the study and that participants would act differently in classroom, limiting external validity. To extend external validity, future studies should test the effect of Instagram-framed pictures on situational ILM in a real classroom embedded in a realistic academic task, as Ku et al. (2014) and Vansteenkiste et al. (2005) did.

7 Conclusion

The present study demonstrated that the primary use of Instagram has a platform-specific effect on materialism compared to the primary use of other social media platforms, according to which people who primarily use Instagram tend to be more materialistic. Longitudinal studies would need to clarify whether this relationship remains stable over time. In addition, studies that address the issue of materialism should more specifically shed light on Instagram use or include it as a control variable. Furthermore, the state of research on social media use in higher education was expanded. Individuals with lower PSMU showed less situational ILM (enjoyment) after exposure to luxury Instagram-framed pictures than those exposed to nature or no pictures. At the same time, individuals with higher PSMU showed higher situational ILM (enjoyment) after being exposed to luxury Instagram-framed pictures than those exposed to nature or no pictures. These findings contribute to the growing literature on social media use in higher education. Social media is an essential part of the everyday life of children, adolescents, and young adults and is relatable to this age group (Vaterlaus et al., 2016). Previous studies found that social media use and the integration of elements of popular social media platforms in higher education enhance ILM, engagement, and creativity and capture interest (Gulzar et al., 2022; Malik et al., 2020; Samuels-Peretz et al., 2017). This study suggests that exposure to neither Instagram-framed luxury nor nature pictures hurts situational ILM so that Instagram-framed pictures can be integrated into courses without worrying about undermining ILM. Educational institutions should embrace the proximity of social media platforms to students' lives to incentivize ILM. Therefore, future studies should further explore how integrating elements of popular social media platforms can profitably enhance situational ILM in higher education without fostering materialism or other problematic behavior like PSMU.

Data availability

Data used in this research are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Notes

Participants of this platform receive points, which they can use to acquire participants for their studies.

References

Alt, D., & Boniel-Nissim, M. (2018). Links between Adolescents’ Deep and Surface Learning Approaches, Problematic Internet Use, and Fear of Missing Out (FoMO). Internet Interventions,13, 30–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.invent.2018.05.002

American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. American Psychiatric Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

Aru, J., & Rozgonjuk, D. (2022). The effect of smartphone use on mental effort, learning, and creativity. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 26(10), 821–823. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2022.07.002

Ashikali, E. M., & Dittmar, H. (2012). The effect of priming materialism on women’s responses to thin-ideal media. British Journal of Social Psychology,51(4), 514–533. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8309.2011.02020.x

Auxier, B., & Anderson, M. (2021). Social media use in 2021. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2021/04/07/social-media-use-in-2021/

Bauer, M. A., Wilkie, J. E. B., Kim, J. K., & Bodenhausen, G. V. (2012). Cuing consumerism: Situational materialism undermines personal and social well-being. Psychological Science,23(5), 517–523. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797611429579

Boer, M., Stevens, G. W., Finkenauer, C., de Looze, M. E., & van den Eijnden, R. J. (2021). Social media use intensity, social media use problems, and mental health among adolescents: Investigating directionality and mediating processes. Computers in Human Behavior,116, 106645. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106645

Boer, M., Stevens, G., Finkenauer, C., & van den Eijnden, R. (2020). Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder-symptoms, social media use intensity, and social media use problems in adolescents: Investigating directionality. Child Development,91(4), e853–e865. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13334

Brailovskaia, J., & Margraf, J. (2021). The relationship between burden caused by coronavirus (Covid-19), addictive social media use, sense of control and anxiety. Computers in Human Behavior,119, 106720. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2021.106720

Brislin, R. W. (1970). Back-translation for cross-cultural research. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology,1(3), 185–216. https://doi.org/10.1177/135910457000100301

Buijzen, M., & Valkenburg, P. M. (2003). The effects of television advertising on materialism, parent–child conflict, and unhappiness: A review of research. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology,24(4), 437–456. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0193-3973(03)00072-8

Burroughs, J. E., & Rindfleisch, A. (2002). Materialism and well-being: A conflicting values perspective. Journal of Consumer Research,29(3), 348–370. https://doi.org/10.1086/344429

Caruso, E. M., Vohs, K. D., Baxter, B., & Waytz, A. (2013). Mere exposure to money increases endorsement of free-market systems and social inequality. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General,142(2), 301–306. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029288

Chan, K., Zhang, H., & Wang, I. (2006). Materialism among adolescents in urban China. Young Consumers,7(2), 64–77. https://doi.org/10.1108/17473610610701510

Chen, Y., Li, M., Guo, F., & Wang, X. (2023). The effect of short-form video addiction on users’ attention. Behaviour & Information Technology,42(16), 2893–2910. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2022.2151512

Chen, Y., Yao, M., & Yan, W. (2014). Materialism and well-being among Chinese college students: The mediating role of basic psychological need satisfaction. Journal of Health Psychology,19(10), 1232–1240. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105313488973

Cheng, C., Lau, Y. C., Chan, L., & Luk, J. W. (2021). Prevalence of social media addiction across 32 nations: Meta-analysis with subgroup analysis of classification schemes and cultural values. Addictive Behaviors,117, 106845. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2021.106845

Cheung, G. W., Cooper-Thomas, H. D., Lau, R. S., & Wang, L. C. (2023). Reporting reliability, convergent and discriminant validity with structural equation modeling: A review and best-practice recommendations. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 1–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-023-09871-y

Chu, S. C., Kamal, S., & Kim, Y. (2013). Understanding consumers’ responses toward social media advertising and purchase intention toward luxury products. Journal of Global Fashion Marketing,4(3), 158–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/20932685.2013.790709

Cleveland, M., Iyer, R., & Babin, B. J. (2023). Social media usage, materialism and psychological well-being among immigrant consumers. Journal of Business Research,155, 113419. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2022.113419

Deloitte. (2019). Global powers of luxury goods 2019: Bridging the gap between the old and the new. Retrieved December 17, 2023, from https://www2.deloitte.com/gr/en/pages/consumer-business/articles/2019-global-powers-of-luxury-goods.html

Dittmar, H., Bond, R., Hurst, M., & Kasser, T. (2014). The relationship between materialism and personal well-being: A meta-analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,107(5), 879–924. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037409

Ennemoser, M., & Schneider, W. (2007). Relations of television viewing and reading: Findings from a 4-year longitudinal study. Journal of Educational Psychology,99(2), 349–368. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.99.2.349

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang, A. G. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods,41(4), 1149–1160. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149

Feierabend, S., Rathgeb, T., Kheremand, H., & Glöckler, S. (2021). KIM-Studie 2020: Kindheit, Internet, Medien [Basisuntersuchung zum Medienumgang 6- bis 13-Jähriger]. Retrieved November 5, 2023, from https://www.mpfs.de/studien/kim-studie/2020/

Festinger, L. (1954). A theory of social comparison processes. Human relations,7(2), 117–140. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872675400700202

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of marketing research,18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104

Gao, J., Zheng, P., Jia, Y., Chen, H., Mao, Y., Chen, S., Wang, Y., Fu, H., & Dai, J. (2020). Mental health problems and social media exposure during COVID-19 outbreak. PLoS ONE,15(4), e0231924. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0231924

Goldberg, M. E., Gorn, G. J., Peracchio, L. A., & Bamossy, G. (2003). Understanding Materialism Among Youth. Journal of Consumer Psychology,13(3), 278–288. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327663JCP1303_09

Griffiths, M. D. (2018). Adolescent social networking: How do social mediaoperators facilitate habitual use? Education and Health, 36(3), 66–69. http://irep.ntu.ac.uk/id/eprint/35779/

Griffiths, M. D., & Nuyens, F. (2017). An overview of structural characteristics in problematic video game playing. Current Addiction Reports,4(3), 272–283. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-017-0162-y

Grouzet, F. M. E., Kasser, T., Ahuvia, A., Dols, J. M. F., Kim, Y., Lau, S., Ryan, R. M., Saunders, S., Schmuck, P., & Sheldon, K. M. (2005). The structure of goal contents across 15 cultures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,89(5), 800–816. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.89.5.800

Guay, F., Chanal, J., Ratelle, C. F., Marsh, H. W., Larose, S., & Boivin, M. (2010). Intrinsic, identified, and controlled types of motivation for school subjects in young elementary school children. The British Journal of Educational Psychology,80(Pt 4), 711–735. https://doi.org/10.1348/000709910X499084

Gulzar, M. A., Ahmad, M., Hassan, M., & Rasheed, M. I. (2022). How social media use is related to student engagement and creativity: Investigating through the lens of intrinsic motivation. Behaviour & Information Technology,41(11), 2283–2293. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2021.1917660

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2009). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Prentice-Hall.

Hassenzahl, M. (2004). Beautiful objects as an extension of the self: A reply. Human-Computer Interaction,19(4), 377–386. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327051hci1904_7

Hayes, A. F. (2018). An introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

Heidig, S., Müller, J., & Reichelt, M. (2015). Emotional design in multimedia learning: Differentiation on relevant design features and their effects on emotions and learning. Computers in Human Behavior,44, 81–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.11.009

Hendijani, R., Bischak, D. P., Arvai, J., & Dugar, S. (2016). Intrinsic motivation, external reward, and their effect on overall motivation and performance. Human Performance,29(4), 251–274. https://doi.org/10.1080/08959285.2016.1157595

Holzer, J., Lüftenegger, M., Käser, U., Korlat, S., Pelikan, E., Schultze-Krumbholz, A., Spiel, C., Wachs, S., & Schober, B. (2021). Students’ basic needs and well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic: A two-country study of basic psychological need satisfaction, intrinsic learning motivation, positive emotion and the moderating role of self-regulated learning. International Journal of Psychology,56(6), 843–852. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12763

Hootsuite. (2022). Social trends in 2022. Retrieved November 14, 2023, from https://www.hootsuite.com/de/ressourcen/digital-trends

Instagram. (2017). Experience luxury on instagram. Retrieved November 2, 2023, from https://business.instagram.com/a/insights/luxury

Jameel, A., Khan, S., Alonazi, W. B., & Khan, A. A. (2024). Exploring the impact of social media sites on compulsive shopping behavior: The mediating role of materialism. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 171–185. https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S442193

Jaspers, E. D., & Pieters, R. G. (2016). Materialism across the life span: An age-period-cohort analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 111(3), 451. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/pspp0000092

Jiang, R., & Chia, S. C. (2009). The direct and indirect effects of advertising on materialism of college students in China. Asian Journal of Communication,19(3), 319–336. https://doi.org/10.1080/01292980903039020

Karapanos, E., Teixeira, P., & Gouveia, R. (2016). Need fulfillment and experiences on social media: A case on Facebook and WhatsApp. Computers in Human Behavior,55, 888–897. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.10.015

Kasser, T. (2016). Materialistic values and goals. Annual Review of Psychology,67(1), 489–514. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-122414-033344

Kasser, T., Rosenblum, K. L., Sameroff, A. J., Deci, E. L [Edward L.], Niemiec, C. P., Ryan, R. M., Árnadóttir, O., Bond, R., Dittmar, H., Dungan, N., & Hawks, S. (2014). Changes in materialism, changes in psychological well-being: Evidence from three longitudinal studies and an intervention experiment. Motivation and Emotion, 38(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-013-9371-4

Kasser, T., Ryan, R. M., Couchman, C. E., & Sheldon, K. M. (2004). Materialistic values: Their causes and consequences. In T. Kasser & A. D. Kanner (Eds.), Psychology and consumer culture: The struggle for a good life in a materialistic world (3. print, pp. 11–28). American Psychological Assoc. https://doi.org/10.1037/10658-002

Katz, E., Blumler, J. G., & Gurevitch, M. (1973). Uses and gratifications research. The Public Opinion Quarterly, 37(4), 509–523. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2747854

Kim, H., Callan, M. J., Gheorghiu, A. I., & Matthews, W. J. (2017). Social comparison, personal relative deprivation, and materialism. British Journal of Social Psychology,56(2), 373–392. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12176

King, R. B. (2020). Materialism is detrimental to academic engagement: Evidence from self-report surveys and linguistic analysis. Current Psychology,39(4), 1397–1404. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-018-9843-5

King, R. B., & Datu, J. A. D. (2017). Materialism does not pay: Materialistic students have lower motivation, engagement, and achievement. Contemporary Educational Psychology,49, 289–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2017.03.003

Kircaburun, K., & Griffiths, M. D. (2018). Instagram addiction and the Big Five of personality: The mediating role of self-liking. Journal of Behavioral Addictions,7(1), 158–170. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.7.2018.15

Ku, L., Dittmar, H., & Banerjee, R. (2012). Are materialistic teenagers less motivated to learn? Cross-sectional and longitudinal evidence from the United Kingdom and Hong Kong. Journal of Educational Psychology,104(1), 74–86. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025489

Ku, L., Dittmar, H., & Banerjee, R. (2014). To have or to learn? The effects of materialism on British and Chinese children’s learning. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,106(5), 803–821. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036038

Lange, F. A. (1925). The history of materialism. Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Limniou, M., Ascroft, Y., & McLean, S. (2022). Differences between Facebook and Instagram usage in regard to problematic use and well-being. Journal of Technology in Behavioral Science,7(2), 141–150. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41347-021-00229-z

Lin, J. H. (2016). Need for relatedness: A self-determination approach to examining attachment styles, Facebook use, and psychological well-being. Asian Journal of Communication,26(2), 153–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/01292986.2015.1126749

Maio, G. R., Pakizeh, A., Cheung, W. Y., & Rees, K. J. (2009). Changing, priming, and acting on values: Effects via motivational relations in a circular model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,97(4), 699–715. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016420

Malik, M. J., Ahmad, M., Kamran, M. R., Aliza, K., & Elahi, M. Z. (2020). Student use of social media, academic performance, and creativity: The mediating role of intrinsic motivation. Interactive Technology and Smart Education,17(4), 403–415. https://doi.org/10.1108/ITSE-01-2020-0005

Marengo, D., Angelo Fabris, M., Longobardi, C., & Settanni, M. (2022). Smartphone and social media use contributed to individual tendencies towards social media addiction in Italian adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic. Addictive Behaviors,126, 107204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2021.107204

Marino, C., Canale, N., Melodia, F., Spada, M. M., & Vieno, A. (2021). The overlap between problematic smartphone use and problematic social media use: A systematic review. Current Addiction Reports,8(4), 469–480. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-021-00398-0

Marino, C., Gini, G., Angelini, F., Vieno, A., & Spada, M. M. (2020). Social norms and e-motions in problematic social media use among adolescents. Addictive Behaviors Reports,11, 100250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.abrep.2020.100250

Marwick, A. E. (2015). Instafame: Luxury selfies in the attention economy. Public Culture,27(1), 137–160. https://doi.org/10.1215/08992363-2798379

McGeown, S. P., Putwain, D., Simpson, E. G., Boffey, E., Markham, J., & Vince, A. (2014). Predictors of adolescents’ academic motivation: Personality, self-efficacy and adolescents’ characteristics. Learning and Individual Differences,32, 278–286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2014.03.022

Middleton, M. J., & Midgley, C. (1997). Avoiding the demonstration of lack of ability: An underexplored aspect of goal theory. Journal of educational psychology,89(4), 710. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.89.4.710

Min, T. S., & Hashim, H. (2022). Boosting students’ motivation in learning descriptive writing through Instagram. Creative Education,13(3), 913–928. https://doi.org/10.4236/ce.2022.133060

Moldes, O., & Ku, L. (2020). Materialistic cues make us miserable: A meta-analysis of the experimental evidence for the effects of materialism on individual and societal well‐being. Psychology & Marketing,37(10), 1396–1419. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21387

Müller, A., Smits, D. J., Claes, L., Gefeller, O., Hinz, A., & de Zwaan, M. (2013). The German version of the material values scale. GMS Psycho-Social-Medicine, 10. https://doi.org/10.3205/2Fpsm000095