Abstract

This study investigates healthcare professionals’ acceptance of video conferences for in-service training in terms of performance expectancy and social influence. Furthermore, it attempts to determine which properties of video conferences influenced and predicted the adoption of video conferencing technology. We employed the cross-sectional survey research design, one of the descriptive research designs. The participants consisted of 181 physicians from a medical specialty society. To collect data, we used the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology-2 (UTAUT-2) scale. Findings revealed that being able to ask questions during the video conferences, not paying for participation, timing problems, and lack of social interaction predicted the acceptance of video conferences for in-service training regarding performance expectancy and social influence among physicians. This article offers practical recommendations for professionals to adopt and maximize the use of videoconferencing for in-service training. The findings of this study will shed light on future practices and studies regarding the use of video conferencing systems for in-service training by revealing the preferences of physicians and the factors affecting their acceptance behavior.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The rapid evolution of medicine necessitates continuous professional development for healthcare professionals. Video conferencing has emerged as a valuable tool for in-service training (IST), offering opportunities for real-time communication and interaction despite geographical barriers. This technology presents several advantages, including eliminating travel requirements, reducing environmental impact, and saving time and costs (Arslan & Şahin, 2013; Gaolyan et al., 2022; Gillies, 2008).

The COVID-19 pandemic further highlighted the importance of video conferencing in IST. With limitations on face-to-face interactions, video conferencing became the primary method for healthcare professionals to access essential scientific information on diagnosing and treating novel diseases (Sayıner & Ergönül, 2021; Wong et al., 2020). Studies suggest that healthcare professionals generally hold positive views on using video conferencing for IST due to its convenience and time-saving benefits (Baturay, 2011; Donovan et al., 2020; Gaolyan et al., 2022; Güngör, 2020).

However, video conferencing is not without limitations. While the lack of social interaction is a commonly cited disadvantage across various professional fields (Arslan & Şahin, 2013; Maher & Prescott, 2017), it may hold less significance for healthcare professionals compared to the advantages offered by video conferencing. Physicians, already juggling patient care and research alongside professional development, find video conferencing particularly appealing due to its flexibility in time management (Baturay, 2011; Reis et al., 2022).

Despite the growing adoption of video conference in healthcare IST, limited research has investigated user acceptance and the specific technology features that influence it. The Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology-2 (UTAUT-2) model (Venkatesh et al., 2012) offers a framework to investigate this concept. Within UTAUT-2, two key sub-dimensions are particularly relevant: performance expectancy (PE) and social influence (SI). PE reflects an individual’s belief in the technology’s ability to enhance professional performance, while SI captures the perceived pressure from others to use the technology (Venkatesh et al., 2003).

This study aims to examine the acceptance of video conferencing technology among physicians who participated in videoconference-based IST during the COVID-19 pandemic in Turkey. We will specifically focus on how performance expectancy and social influence impact their acceptance of video conferencing for future IST endeavors.

1.1 Literature review

Video conferencing, the processes in which real-time training, meetings, presentations, and collaborations are carried out, or new products and services are offered over the Internet (Loch & Leushle, 2008), started to be used in the 1990s and have been popular since the early 2000s thanks to their rapidly developing technologies (Zoumenou et al., 2015). Video conferences are preferred in in-service training (IST), as they offer more opportunities for instant communication and interaction among distance education solutions (Güngör, 2020). Video conferences, which provide equality of opportunity in the professional development of professionals in distant geographical locations, create benefits such as not requiring transportation, preventing environmental pollution, reducing costs, and saving time; therefore, video conferencing systems are in demand in the in-service training of professionals from different fields (Arslan & Şahin, 2013; Gaolyan et al., 2022; Gillies, 2008; Macht et al., 2022; Maher & Prescott, 2017; Rubinger et al., 2020).

Other important factors that make video conferences an alternative to face-to-face training in IST are that they allow two-way instant communication and interaction (Adipat, 2021; Baturay, 2011; Emre, 2019; Gaolyan et al., 2022; Gegenfurtner et al., 2020; Gillies, 2008; Nguyen et al., 2021; Turgut, 2010), are user-friendly (Nguyen et al., 2021; Wang & Hsu, 2008), and can be recorded (Gegenfurtner et al., 2020; Wang & Hsu, 2008). Although video conferences offer more interaction opportunities than asynchronous distance education methods, they cannot replace face-to-face training, and users can feel a lack of social interaction (Arslan & Şahin, 2013; Gaolyan et al., 2022; Maher & Prescott, 2017). Having issues with the hardware, the Internet connection, or the software used for videoconferencing can be distracting and have a big impact on how well it works, as well as on the participants’ motivation and expectations of what they can gain from it (Arslan & Şahin, 2013; Başaran, 2014; Gaolyan et al., 2022; Gegenfurtner et al., 2020; Nguyen et al., 2021; Turgut, 2010; Wang & Hsu, 2008). Video conferences require participation during a specific time frame, and bad timing is among the factors that can negatively affect participation (Coetzee et al., 2018; Gegenfurtner et al., 2020; Maher & Prescott, 2017). Some studies emphasize that video conferences are useful for small groups only when conditions are not suitable for face-to-face training (Bower et al., 2012; Maher & Prescott, 2017). Therefore, it is necessary to determine the factors that may affect the efficient use of video conferences in in-service training.

1.1.1 Use of video conferencing for in-service training in the healthcare industry

Change and renewal in the field of medicine are very rapid, and health professionals need to be constantly updated professionally (Akalın, 2002; Baturay, 2011; Gaolyan et al., 2022; Güngör, 2020; Macht et al., 2022). During the COVID-19 pandemic, the workload of healthcare professionals increased, and quickly accessing scientific, accurate, and yet constantly updated information on the diagnosis and treatment of the new disease became even more critical (Sayıner & Ergönül, 2021; Wong et al., 2020). However, during the pandemic, because of social distancing restrictions, face-to-face ISTs were impossible, and distance education became the primary method of education (Ahmed et al., 2020; García et al., 2021; Nguyen et al., 2021; Osei et al., 2022; Sayıner & Ergönül, 2021). As part of IST, scientific meetings like congresses, symposiums, and conferences were held so that doctors could get the most up-to-date information. These meetings were continued by the relevant professional organizations using distance learning methods (Gaolyan et al., 2022).

A limited number of studies show that physicians, nurses, and other health professionals have positive opinions about using video conferencing for IST due to advantages such as saving time and easy and fast access to current professional knowledge (Baturay, 2011; Donovan et al., 2020; Gaolyan et al., 2022; Güngör, 2020). Although the studies examining the use of video conferencing for IST in different professional fields show that the most critical disadvantage is the lack of social interaction (Arslan & Şahin, 2013; Maher & Prescott, 2017), it can be said that this is not the most prominent issue for health professionals when compared to the advantages of video conferencing (Gaolyan et al., 2022). Physicians must receive or give education in addition to serving patients and conducting research, and they may have difficulties allocating time and focusing on all these tasks (Baturay, 2011; Reis et al., 2022). At this point, distance education technologies such as video conferences come into play and provide solutions to support the vocational training of healthcare professionals (Baturay, 2011).

1.1.2 Acceptance of video conferencing technology in the healthcare industry

In our age, the widespread use of information and communication technologies in daily and professional life forces individuals to use these technologies. However, compulsory use may not mean these technologies are accepted (Yılmaz & Kavanoz, 2017). Research on the acceptance and use of information technologies is one of the most established branches of information systems research (Venkatesh & Davis, 2000; Venkatesh et al., 2007). Models developed to investigate technology acceptance contribute to understanding the drivers of technology adoption to proactively design interventions for target users in a variety of contexts, from education to marketing, and provide a useful tool for managers to assess the success probability of the relevant technology (Venkatesh et al., 2003).

The Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology-2 (UTAUT-2) developed by Venkatesh et al. (2012) shows that performance expectancy, effort expectancy, social influence, facilitating conditions, hedonic motivation, price value, and habit dimensions are direct determinants of behavioral intention and the proceeding use of technology. It presents a model in which variables of gender, age, experience, and voluntary use predict these constructs. Venkatesh et al. (2012) reported that in the context of consumers, UTAUT-2 explained 74% of the variance regarding behavioral intention and 52% regarding technology use.

Two of the eight sub-dimensions of UTAUT-2 are performance expectancy (PE) and social influence (SI) (Venkatesh et al., 2012). PE indicates the degree of individuals’ personal belief about how much a particular technology will contribute to their professional performance, and it is the strongest predictor of the intention to use the technology in the future. On the other hand, SI is the extent to which users perceive that the other people in their lives believe the individual should use a particular technology (Venkatesh et al., 2003).

Research on user perception and use of video conferencing technology within the UTAUT-2 paradigm is limited, particularly in relation to PE and SI. Based on these two sub-dimensions in UTAUT-2, we found no study that addresses the acceptance of video conferences. Additionally, no study examines which properties of video conferencing, perceived positively and negatively, affect the variables of technology acceptance models. Furthermore, there is a lack of study on the impact of specific attributes of video conferencing technology on technology acceptance models among physicians. Previous studies have not specifically examined healthcare workers, suggesting that user characteristics may vary in this setting.

A medical specialty society operating in the field of clinical microbiology and infectious diseases in Turkey continued its scientific meetings within the scope of IST via video conference during the pandemic. The primary purpose of this study is to examine the acceptance of physicians who participated in those video conferences during the pandemic in the context of PE and SI.

The following research questions were created to examine these issues:

-

(1)

How do physicians’ preferences for IST video conferences cluster in terms of PE and SI dimensions?

-

(2)

What properties of IST video conferences are decisive on the PE and SI dimensions of physicians’ acceptance behaviors?

-

(3)

What properties of IST video conferences predicted the PE and SI dimensions of physicians’ acceptance behaviors?

1.1.3 Significance of research

We believe that the findings of this study, which investigates the acceptance of video conferences as part of ISTs by physicians in the fields of infectious disease and clinical microbiology, will shed light on future practices and studies regarding the use of video conferencing systems for in-service training by revealing the preferences of physicians regarding video conferences and the factors affecting their acceptance behavior. In addition, examining the positive properties and limitations of video conferences for IST in terms of technology acceptance will contribute to the literature.

2 Method

2.1 Research design

The present study used a cross-sectional survey research design, one of the descriptive research designs. Physicians who voluntarily attended video conferences for IST organized during the COVID-19 pandemic by their medical specialty society provided data in a single instance.

2.2 Participants

The study participants were members of the above-mentioned medical specialty society, which had 2445 members by November 2021, and they voluntarily attended video conferences. The questionnaire and the scale were sent electronically to all members of society under pandemic conditions. Among them, 184 physicians from 41 different provinces and foreign locations responded to the questionnaire and the scale, and three of them were excluded because of missing data. Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of 181 physicians, who made up 7% of the total members of society and had an average age of 44.3, as well as information about their participation in video conferences.

The data presented in Table 1 shows that 75% of the participants were women, and 80% received at least ten or more ISTs via video conference. According to the data regarding the place of participation in video conferencing, where multiple selections were possible, almost all physicians stated that they attended video conferences from their homes (98.9%) and more than one-third of them from their workplaces (37.6%). Some physicians said they attended from alternative locations, such as “from their son’s nursery” and “on the road.” Again, according to data where multiple selections were possible, physicians stated that they mostly used mobile devices (67.4% smartphones, 63% laptops, and 8.8% tablets) while attending video conferences. In addition, most of them stated that their time interval preference for video conferences for IST was between 20.00 and 22.00 (76.8%).

The question “Was your participation in video conferences beneficial to learn about innovations and changes in your daily practices for diagnosis and treatment?” which was posed to the physicians, was answered with a ratio of almost two out of three (61.3%) as “it was highly beneficial”, while 8.8% stated that they benefited “partially or not at all.” The findings revealed that more than 90% of physicians found using video conferences for in-service training purposes professionally beneficial.

2.3 Data collection tools

The data collection tools used in the study consisted of a questionnaire and a scale. The questionnaire consisted of the Personal Information Form (PIF) and the Video Conference Participation Information Form (VCPIF), with 18 questions. VCPIF was used to determine the frequency of attendance at video conferences, the devices they used while attending, where they attended from, and their preferences regarding video conferences. In addition, the properties that were thought to affect their participation in video conferences positively or negatively were selected from the literature (Arslan & Şahin, 2013; Başaran, 2014; Gaolyan et al., 2022; Gegenfurtner et al., 2020; Maher & Prescott, 2017; Nguyen et al., 2021; Turgut, 2010; Wang & Hsu, 2008) and presented to physicians. Table 2 shows these properties:

The other data collection tool used was the Turkish version of the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology-2 (UTAUT-2) scale (Yılmaz & Kavanoz, 2017). The Cronbach alpha values of the 28-item scale varied between 0.76 and 0.93 according to the sub-dimensions, and it was similar to the original scale in terms of reliability (Yılmaz & Kavanoz, 2017).

In the present study, items of the original scale were rearranged in the context of ‘IST via video conferencing’. Since participation in the video conferences within the scope of this research was free, three items on the scale related to price value were excluded. Therefore, the scale consisted of seven sub-dimensions and 25 items. Selections related to agreement/disagreement with the items were on a five-point Likert-type scale.

2.3.1 Validity and reliability

In the present study, because the UTAUT-2 scale was applied to physicians in a different context, exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was used first. However, despite the different rotation techniques and the items that were attempted to be discarded, a seven-factor structure (the price value was excluded) could not be obtained. The findings revealed that the data set obtained from the physicians did not coincide with the item distributions on the original scale, and the UTAUT-2 model was not compatible with the data set at hand.

Items unsuitable for the dataset from which the original factor structure could not be obtained were removed from the scale. It was then seen that seven items from the PE and SI sub-dimensions were consistently assigned to the right factors with the original scale when the EFA was done again. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) value for the two-dimensional structure obtained was 0.839, and the result of the Bartlett test was statistically significant (X2 = 890.210, Sd = 21, p < .001). The distribution of the factors formed after applying the Direct Oblimin rotation technique is shown in Table 3.

As shown in Table 3, the loads of the two factors obtained vary between 0.924 and 0.758, explaining 63.800% of the total variance. Cronbach’s alpha values were calculated as 0.86 and 0.92 in the analyses performed to determine the reliability of the obtained structure. Since these values are above the generally accepted lower limit of 0.70, it can be said that the data obtained from the scale are reliable (Büyüköztürk, 2018). Participants can get a maximum of 35 and a minimum of 7 points from the five-point Likert-type scale.

2.4 Research process

2.4.1 Video conferences subject to research

The society, which operates in the field of clinical microbiology and infectious diseases in Turkey, held weekly video conferences with the responsibility of conveying up-to-date and accurate scientific information to its members working at the forefront in the fight against COVID-19. In this context, a total of 91 IST video conferences were held between March 17, 2020, and November 30, 2021. The topics of the video conferences were determined one month in advance, and the speakers were selected from leading experts in infectious diseases, clinical microbiology, or related fields. The details of each video conference were added to the calendar on the society’s website and announced on social media accounts one week before the video conference, with a notifying email also being sent to society members.

The number of participants ranged from 57 to 1193 per video conference, with a mean of 335. Only the speakers were displayed on the screen during the video conference sessions, besides PowerPoint presentations and various visual materials. Participants raised their questions and thoughts by typing in the video conference interface’s “Question-Answer” and “Comments” sections. Only one of the video conferences was held at noon; the rest were held in the evening. Thirty-seven video conferences held in the evening started at 20:00 and 53 at 21:00. Except for two one-hour conferences, they were planned as 90-minute sessions.

2.4.2 Data collection process and ethics

Before the data collection process, the ethics committee’s approval of the university where the master’s thesis was conducted, the approval of the authors of the UTAUT-2 scale, and the permission of the board of directors of the relevant association were obtained. All data collection tools were gathered in a single electronic form. The form link was sent to all association members via the society’s email account, and the data was collected electronically and on a voluntary basis with consent.

2.5 Data processing and analysis

Frequency and percentage calculations were conducted for demographic data analysis. EFA was used in the validity and reliability studies of the UTAUT-2 scale, and the internal consistency between the items was checked. Normal distribution assumptions were based on skewness and kurtosis values.

Cluster analysis, an exploratory tool, was conducted to determine how physicians clustered in the context of PE and SI, and a two-stage clustering method was used. This clustering method is used when the number of clusters is not certain at the beginning, and both continuous and categorical variables are present in the data set (Uçar, 2009). For cluster analysis, log-likelihood was used to measure distance, and Schwards’ Bayesian criterion, the only option in data sets where continuous and categorical variables were carried out together, was used as a clustering criterion. Kruskal-Wallis H analysis was used to find differences between clusters that were not normally distributed. Bonferroni correction was used to look at the results of multiple comparison tests.

Mann-Whitney U analysis was used because there was no normal distribution in the analyses performed to understand the effects of videoconferencing properties on dependent variables. Multiple regression analysis was conducted to understand the predictors of the dependent variables of the properties determined to affect the dependent variable. Before this analysis, it was determined that the scores of the dependent variables were normally distributed in the whole group. Before the regression analysis, outliers were removed by examining boxplots for both dependent variables and determining those with a standard residual value greater than 3. At the end of these procedures, regression analyses were performed on 178 subjects for the dependent variable of PE and 175 subjects for the SI variable. All analyses were conducted using SPPS 28.0, and the confidence interval was set as 0.05.

3 Results

3.1 Findings regarding the first research question

A two-stage clustering analysis was applied to answer the question, “How do physicians’ preferences for IST video conferences cluster regarding PE and SI dimensions?“. Table 4 shows the mean PE (4.19) and SI (3.66) scores of 181 participants.

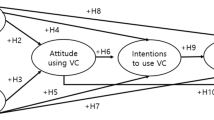

Besides PB and SE, cluster analysis included variables such as gender, seniority, and preferences for video conferences and face-to-face meetings. A three-cluster model with a ‘good’ clustering quality (Average silhouette > 0.5) was obtained. In the model, physicians’ preference for attending IST face-to-face or via video conference was the only determinative factor. Accordingly, three clusters were identified who stated that they “especially preferred face-to-face meetings,” “it does not matter,” and “especially preferred video conferences” (Fig. 1).

In order to understand the success of the cluster analysis, it was checked whether there was a statistically significant difference between the groups. Since the mean PE and SI scores were not normally distributed within the groups, the non-parametric Kruskal Wallis test was applied, and the difference was found significant between at least two clusters regarding both PE and SI scores (p < .001). Table 5 shows the clusters of the physicians, the distribution of their preferences, and the mean PE and SI scores within the clusters.

Table 6 shows the Mann-Whitney-U multiple comparison results displaying the difference among clusters.

According to Table 6, in terms of PE, there was a significant difference between the other two clusters in favor of the cluster consisting of those who especially preferred video conferences. The PE score averages of the physicians in the third cluster, especially those who preferred video conferences (X̄=4.59), were in the range of “Strongly agree,” while the PE score averages of the clusters of those who preferred face-to-face meetings and said “it does not matter” were in the “Agree” range.

Regarding SI, the significant difference was only between the first cluster, which preferred face-to-face meetings for IST, and the other two clusters. According to the findings, the SI mean scores of the cluster, which included those who preferred face-to-face meetings for IST, were in the “Neutral” range, while the clusters of those who said “it does not matter” and those who preferred video conferences were in the “Agree” range.

3.2 Findings regarding the second research question

For the second research question, analyses were conducted to determine the positive and negative properties that may impact the PE and SI dimensions. In the data collection tool, physicians were asked to choose ‘Yes’ if these properties affect their participation in video conferences and ‘No’ if not.

3.2.1 Findings regarding the properties affecting the PE dimension

PE is defined as the degree to which an individual believes that using technology will positively affect job performance (Venkatesh et al., 2003). Table 7 shows the Mann-Whitney U test results for the positive characteristics of the PE dimension of the UTAUT-2 scale.

Table 7 shows the positive properties that had a statistically significant effect on PE: “no need for transportation,” “being able to ask questions,” and “being more comfortable.” Physicians who chose these properties had statistically significantly higher PE scores than those who did not. According to the findings, physicians thought these three properties of video conferences would positively reflect on their medical performance. Among the properties, “being able to ask questions” had the highest significance value (p < .001).

The Mann-Whitney U test results regarding the properties that negatively affected the PD sub-dimension are given in Table 8.

According to Table 8, “timing problems” and “lack of social interaction” had statistically significant negative effects on PE. The physicians who chose these two properties had significantly lower PE scores than the physicians who did not (p < .05). The negative effect of “lack of social interaction” was very strong (p < .001).

3.2.2 Findings regarding the properties affecting the SI dimension

The SI dimension measures the degree to which physicians perceive that people they care about, such as friends, colleagues, or family members, believe the individual should use video conferences (Venkatesh et al., 2003). The Mann-Whitney U test results regarding the properties that positively affect the SI dimension are given in Table 9.

Table 9 shows that the “free of charge” and “User-friendly video conferencing interface” properties significantly affected the SI dimension. While the SI scores of the physicians who selected the “free of charge” property were statistically significantly higher than those of the physicians who did not, the SI scores of the physicians who did not select the “user-friendly video conferencing interface” property were statistically significantly higher.

The analysis results regarding the factors that negatively affected the SI dimension are given in Table 10.

Table 10 shows that the SI dimension was statistically significantly negatively affected by “lack of social interaction” and “timing problems”. Physicians who did not see these as negative factors regarding their participation in video conferences had statistically significantly higher SI scores than the others.

3.3 Findings regarding the third research question

Multiple regression analyses were carried out for both dimensions to seek an answer to the research question, “What properties of IST video conferences predicted the PE and SI dimensions of physicians’ acceptance behaviors?“. After removing three outliers for PE and six for SI, the dataset had a normal distribution. In line with the second research question’s findings, positive and negative properties of IST video conferences that can be expected to predict PE and SI dimensions were used as independent variables and are presented in Table 11:

The findings of the multiple regression analysis conducted with the ‘enter’ method regarding the prediction of the acceptance of video conferences in the context of PE and SI of all bi-valued independent variables coded as ‘significant’ or ‘insignificant’ by the participants are presented in Table 12:

The highest Mahalabonis values in the data set were 15.713 and 9.174 for PE and SI, respectively; the highest Cook’s Distance values were found to be 0.078 and 0.063, respectively. Table 12 shows no multicollinearity (1.011 < VIF < 1.2075) in the models obtained for both independent variables. We looked at the Normal Probability Plot (P-P) of the Regression Standardized Residual and the Scatterplot. Neither model has problems with normality, linearity, homoscedasticity, or the independence of residuals. The models with regression assumptions are as follows:

According to the models, “being able to ask questions” in video conferences predicted physicians’ PE, while “free of charge” predicted SI positively. Video conferences’ timing and low social interaction predicted both PE and SI negatively. The lack of need for transportation, higher comfort than in face-to-face meetings, and user-friendly video conferencing interfaces had no predictive effect on PE and SI, according to the models.

4 Discussion, conclusion and recommendations

This study investigated the acceptance of video conferencing technology in IST by physicians working in infectious diseases and clinical microbiology in the context of PE and SI. Previous studies on the use of video conferencing in IST revealed that healthcare professionals found video conferences beneficial in terms of their professional performance (Baturay, 2011; Donovan et al., 2020; Gaolyan et al., 2022; Güngör, 2020; Macht et al., 2022). Similarly, in this study, more than 90% of physicians stated that video conferences contributed positively to their daily practices regarding learning innovations and changes in patient diagnosis and treatment. Physicians are a professional group amenable to technology and are accustomed to IST to follow up-to-date practices because of their profession. In fact, 80% of the physicians voluntarily participated in at least ten or more IST video conferences.

However, the findings for this study’s first research question show a divergence between PE and SI dimensions regarding the acceptance of videoconferencing technology. The findings showed that physicians with high expectations about the impact of the training they received from this medium on their professional performance were clustered in the cluster that especially prefers video conferences (3rd cluster). On the other hand, physicians who especially preferred face-to-face IST (1st cluster) were more concerned about the social effects of attending video conferences than other groups. The findings of the second and third research questions can be evaluated to better understand physicians’ acceptance of technology in the context of the PE and SI dimensions.

4.1 Positive properties of video conferences and technology acceptance in the context of PE and SI

Studies in the literature have shown that PE is one of the strongest predictors of the intention to use and accept the technology. PE maintains its effect in different conditions, such as voluntary or compulsory use, in different technologies and samples with different characteristics (Khechine et al., 2014; Lakhal et al., 2013; Venkatesh et al., 2003). The physicians who participated in this study were, in a sense, condemned to IST video conferences under pandemic conditions. Due to its high predictiveness, it is important to determine the positive and negative properties of the related technology that affect PE. The present study revealed that the properties “no need for transportation,” “more comfortable,” and “being able to ask questions” had a significant positive effect on physicians’ PE scores related to video conferences; however, only “being able to ask questions” predicted PE in video conferences.

It is frequently emphasized in the literature that IST video conferences create equal opportunities for professionals in remote and dispersed geographical locations, save time, and reduce costs by not requiring transportation (Gaolyan et al., 2022; Maher & Prescott, 2017). The present study’s participants consist of physicians spread over a vast geography. It is an expected result that the participants of this study, whose professional knowledge was critically important in the pandemic conditions and who needed to reach new information about COVID-19 very quickly, thought that accessing video conferences for IST from their place of residence would increase their professional performance.

All the video conferences included in the study were held on weekdays and almost all in the evening; therefore, the participation rate from home is high. In the study conducted by Coetzee et al. (2018) to evaluate participants’ perceptions of video conferences and the effect of video conferences on their academic performance, participants reported that they attended video conferences mainly from their places of accommodation (78%). Gegenfurtner, Zitt, and Ebner’s (2020) research into participants’ reactions to video conferences revealed that they saw accessing video conferences from the comfort of their homes as a significant advantage.

In addition, the high workplace participation rate shows that physicians could attend video conferences while on duty in the institutions where they worked. Physicians can attend IST video conferences without disturbing the routine of their professional and private lives, and this positively affects the acceptance of video conferencing technologies in the context of PE. In the literature, flexibility in location and place is frequently emphasized as one of the most critical advantages of video conferencing (Adipat, 2021; Arslan & Şahin, 2013; Baturay, 2011; Coetzee et al., 2018; Donovan et al., 2020; Gaolyan et al., 2022; Gegenfurtner et al., 2020; Maher & Prescott, 2017; Turgut, 2010); the findings of this study support this point.

Another reason physicians found IST video conferences comfortable may be that they did not need any special equipment to participate in video conferences. Video conferences provide extra flexibility as a result of being accessible from mobile devices (Başaran, 2014; Baturay, 2011; Gegenfurtner et al., 2020; Macht et al., 2022; Maher & Prescott, 2017). The participants of this study stated that they mostly used mobile devices, especially smartphones and laptops, while participating in video conferences, which is in line with the findings of previous studies. In the study conducted by Nguyen et al. (2021), among Vietnamese university students who continued their education remotely during the pandemic period, the participants stated that they mostly used smartphones (79%) and laptop computers (70%) to attend video conferences, while not using desktop computers (9%) much. Another study by Coetzee et al. (2018) found that 80% of the participants used mobile devices such as laptops, tablets, and smartphones while attending video conferences, and desktop computers (20%) were the least used. All of these show that physicians can comfortably participate in video conferences for IST at anytime from anywhere, thanks to their mobile devices, and this positively affects PE.

Two-way instant communication and interaction allow participants to ask questions in video conferences, and this property is seen as one of the most important advantages (Adipat, 2021; Baturay, 2011; Emre, 2019; Gaolyan et al., 2022; Gegenfurtner et al., 2020; Gillies, 2008; Macht et al., 2022; Nguyen et al., 2021; Turgut, 2010). The present study’s findings reveal that “being able to ask questions” in IST video conferences predicts PE. According to Baturay (2011), physicians found video conferences more efficient because all participants had the opportunity to ask questions; they could ask questions more easily and get answers faster. According to a study by Macht et al. (2022), video conferences for in-service training for healthcare professionals enable direct exchange of ideas, questions, and discussions. These findings indicate that colleagues who share knowledge and experience by asking questions rather than relying solely on receiving information from the field expert stand out among the known positive properties of video conferences and should be considered in practice.

In addition to the expected positive results regarding factors affecting PE, we obtained some unexpected results. For example, it was interesting that the property “relevant to learning needs” was not among the factors that positively affected PE. Because professionals generally value video conferences as an opportunity to reach subject experts who are difficult to reach face-to-face and to access up-to-date information that will contribute to their professional performance (Gaolyan et al., 2022; Macht et al., 2022; Maher & Prescott, 2017; Turgut, 2010), " relevant to learning needs” was expected to affect PE. This finding may be interpreted as video conferences incentivizing physicians to attend ISTs, which they may not normally prefer to attend face-to-face because of time and distance barriers.

It was also interesting to see that “being able to watch the recordings later” did not have a significant impact on PE. It is emphasized in the literature that the ability to record and watch video conference sessions is seen as an important advantage (Gegenfurtner et al., 2020). Although video conferences provide flexibility regarding location, they require attendance at a particular time. Watching video conference recordings later may be a significant advantage in overcoming timing problems; however, this property was not highly important in terms of PE for the physicians. It is possible that physicians did not have time to go back and watch the recordings because they were overworked, especially during the pandemic.

The study’s findings reveal that the positive “free of charge” and “user-friendly interface” properties of IST video conferences affect physicians’ beliefs that their family members, friends, and colleagues want them to attend video conferences. Studies from the past have shown that the SI has a big impact on people’s plans to use the relevant technology in the future when they are forced to use it (Başaran, 2014; Khechine et al., 2014; et al., 2013; Venkatesh et al., 2003). However, the present study’s findings, in which physicians who participated in IST video conferences voluntarily, contradicted previous findings.

The cost and pricing structure significantly impact users’ decisions to use technology (Venkatesh et al., 2012). In countries such as Turkey, which have economic difficulties and do not have high income levels, family members may have a priority effect in the context of SI. Therefore, pricing may have a predictive effect on SI. In addition, the participants of this study generally attended the IST video conferences from their homes and in the evening hours, showing that they attended these video conferences by taking away from the time they would otherwise spend with their families. It is also possible that not having to pay for this lost time was seen as an advantage, which may explain the predictive effect in the SI context.

The user-friendly video conferencing interface plays an important role in video conference acceptance (Alfadda & Mahdi, 2021; Emre, 2019; Nguyen et al., 2021; Wang & Hsu, 2008). The present study found that the “user-friendly interface” in IST video conferences was effective on SI but not a predictor. What is remarkable is that physicians with a higher SI score did not mark the interface’s user-friendliness as a positive property. In other words, physicians who place a high value on the interface’s user-friendliness have the perception that their social environment supports them less. These are probably physicians who do not feel competent in using video conferencing technology, and there may be a possibility of ignoring their professional environment’s expectations in this regard. However, the fact that the interface’s user friendliness does not have a predictive effect suggests that this property, although important, is not a determinant of participation in video conferences.

4.2 Negative characteristics of video conferencing and technology acceptance in the context of PE and SI

Findings from the second and third research questions revealed that “timing problems” and “lack of social interaction,” which are negative aspects of video conferences for IST, had negative effects on technology acceptance in both PE and SI dimensions.

The fact that video conferences are synchronous and, therefore, require attendance at a particular time may prevent the participation of people who are not available at that hour (Coetzee et al., 2018; Gegenfurtner et al., 2020; Maher & Prescott, 2017). In the study, the number of physicians who preferred video conferences to be held between 20.00 and 22.00 (77%) and not exceed 60 min (41%) was quite high. Thus, it can be said that physicians have a positive view of the organization of video conferences in a timeframe that belongs to their private lives. However, the findings showed that timing problems negatively predicted both expectations about professional gains and thoughts about the social environment related to these technologies. The risk of being unable to attend the IST because of timing problems lowers the performance expectancy related to video conferencing technology. In this respect, proper scheduling is critical to the technology acceptance of video conferences (Maher & Prescott, 2017).

“Timing problems” have a stronger predictive effect on SI than on PE. This finding can be interpreted as physicians perceiving their close social circle consisting of family members and friends as having problems with the timing of video conferences since they attend video conferences mostly from their homes and during the period belonging to their private lives. It is strongly recommended to consider the preferences of the participants when organizing video conferences for IST to minimize the negative effects of scheduling problems.

Although video conferencing allows simultaneous audio and video communication and provides participants with an experience like face-to-face training, the “lack of social interaction” property is still felt, being seen as one of the most important disadvantages of video conferencing (Alfadda & Mahdi, 2021; Arslan & Şahin, 2013; Maher & Prescott, 2017). Our findings reveal that a lack of social interaction is the strongest negative predictor of technology acceptance in the context of PE. During video conferences, physicians interacted with specialists by asking questions, and they believed this opportunity would increase their professional gains. However, they could not interact and exchange ideas with their colleagues who came together in the digital environment, and they may have seen this as an obstacle to their professional development.

Similarly, a lack of social interaction negatively predicted technology acceptance in the context of SI, and this limitation has the highest coefficient among both dimensions. Apart from family members, colleagues are another group that influences the individual in terms of the SI dimension. Physicians attending IST video conferences value the benefits of interaction with their colleagues; therefore, choosing video conferencing platforms that offer solutions to this problem may somewhat eliminate the lack of social interaction. In addition, the introduction of Web 2.0 tools to increase social interaction in video conferences for IST may have an impact on reducing this negative effect. In video conferences, individuals can express their opinions, make evaluations, or enjoy their time individually or in teams using Web 2.0 tools.

This study’s unexpected finding, which is not included in the research questions, is that the items in the adapted UTAUT-2 scale reveal a structure that does not overlap with the original model. It is thought that this may be because the group of physicians included in the study was homogeneously made up of highly educated people who voluntarily participated in video conferences; after all, they had a positive attitude toward society’s activities. Similarly, Hu et al. (1999) observed that in their study, physicians from various specialties used the TAM model (Davis, 1986) on technology acceptance behaviors related to telemedicine practices. The scale adapted for the purpose revealed different structures than the original TAM model suggested. Compared to other TAM studies, that one said the model wasn’t very good at explaining how doctors’ attitudes and intentions changed over time. This was because doctors were different from other people the model had been used on because of their general skills, ability to learn new technologies, intellectual and cognitive abilities, and the nature of their work (Hu et al., 1999). In addition, Venkatesh et al. (2012) stated that testing UTAUT-2 in different countries with different age groups and technologies would be appropriate. In fact, in their study, they applied UTAUT-2 in the context of mobile Internet use in Hong Kong, where the use of smartphones was widespread (Venkatesh et al., 2012). They stated that the relationships between the findings and variables might change in a country where smartphone use is uncommon or in a sample group consisting of older people (Venkatesh et al., 2012).

4.3 Limitations and future research

There are two main limitations to the study. First, the study employed convenience sampling, and the research setting was a single medical specialty society in Turkey. Furthermore, all participants from the field of clinical microbiology and infectious diseases in Turkey. Therefore, the study’s findings should be interpreted with caution in other contexts. Second, the study relied on self-report surveys, which might be biased in some cases because respondents may incorrectly attribute their experiences and feelings to specific internal or external variables.

In the literature, a limited number of studies evaluate video conferences in the context of technology acceptance and specifically address vocational training video conferences for health professionals. We think investigating other dimensions of technology acceptance models that this study cannot address will shed light on future applications and fill an important gap in the literature.

Data availability

Data available on request from the authors.

References

Adipat, S. (2021). Why web-conferencing matters: Rescuing education in the Time of COVID-19 Pandemic Crisis. Frontiers in Education, 6(6). https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2021.752522

Ahmed, S., Zimba, O., & Gasparyan, A. Y. (2020). Moving towards online rheumatology education in the era of COVID-19. Clinical Rheumatology, 39(11), 3215–3222. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-020-05405-9

Akalın, S. (2002). Improving Continuing Education in Primary Care: Sharing experience [Birinci Basamakta Sürekli Eğitimin Geliştirilmesi: Deneyim Paylaşımı]. Sürekli Tıp Eğitimi Dergisi, 11(6), 215–219. https://www.ttb.org.tr/sted/sted0602/birinci.pdf

Alfadda, H. A., & Mahdi, H. S. (2021). Measuring students’ use of Zoom Application in Language course based on the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM). Journal of Psycholinguistic Research, 50(4), 883–900. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10936-020-09752-1

Arslan, H., & Şahin, İ. (2013). Teachers’ opinions on the use of video conferencing system for delivering ISTs [HİE’lerin video konferans sistemiyle verilmesine yönelik öğretmen görüşleri]. The Journal of Instructional Technologies &Teacher Education, 2(2), 34–41. https://dergipark.org.tr/en/pub/jitte/issue/25081/264700#article_cite

Başaran, B. Ç. (2014). Webinars as instructional toold in English language teaching context Unpublished Masters Thesis, METU, English Language Teaching Department. Ankara.

Baturay, M. H. (2011). Satisfaction of medical educators who received pediatric ecg training via video conferencing and their level of adoption of this technology [Video konferansla pediatrik ekg eğitimi alan tip eğitimcilerinin memnuniyetleri ile Bu Teknolojiyi Benimseme düzeyleri]. Mersin Üniversitesi Eğitim Fakültesi Dergisi, 6(1), 145–160. https://dergipark.org.tr/en/download/article-file/160767

Bower, M., Kennedy, G., Dalgarno, B., Lee, M. J., Kenney, J., & De Barba, P. (2012). Use of media-rich real-time collaboration tools for learning and teaching in Australian and New Zealand universities. In Proceedings Ascilite Wellington 2012, (s. 133–144). https://researchoutput.csu.edu.au/ws/portalfiles/portal/9721076/43282postpub.pdf

Büyüköztürk, Ş. (2018). Handbook of data analysis for social sciences: Statistics, research design, SPSS applications and interpretation [Sosyal Bilimler için veri analizi El kitabı: Istatistik, araştırma deseni, SPSS uygulamaları ve Yorum]. Pegem Akademi.

Coetzee, S. A., Schmulian, A., & Coetzee, R. (2018). Web conferencing-based tutorials: Student perceptions thereof and the effect on academic performance in accounting education. Accounting Education, 27(5), 531–546. https://doi.org/10.1080/09639284.2017.1417876

Davis, F. D. (1986). A technology acceptance model for empirically testing new end-user information systems: theory and result Unpublished Doctoral dissertation, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Donovan, G., Ong, S. K., Song, S., Ndefru, N., Leang, C., Sek, S., Sadate-Ngatchou, P., & Perrone, L. (2020). Remote mentorship using video conferencing as an effective tool to strengthen laboratory quality management in clinical laboratories: Lessons from Cambodia. Global Health: Science and Practice, 8(4), 689–698. https://doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-20-00128

Emre, S. (2019). Webinars for teaching english as a foreign language and for professional development: teacher perceptions Unpublished Masters Thesis, Bilkent University, Ankara.

Gaolyan, T., Kysh, L., Lulejian, A., Dickhoner, J., Sikder, A., & Lee, M. (2022). Lessons learned from organizing and evaluating international virtual training for healthcare professionals. International Journal of Medical Education, 13, 88–89. https://doi.org/10.5116/ijme.6238.459f

García, N. O., Velásquez, M. D., Romero, C. T., Monedero, J. O., & Khalaf, O. (2021). Remote academic platforms in times of a pandemic. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning, 16(21), 121–131. https://doi.org/10.3991/ijet.v16i21.25377

Gegenfurtner, A., Zitt, A., & Ebner, C. (2020). Evaluating webinar-based training: A mixed methods study of trainee reactions toward digital web conferencing. International Journal of Training and Development, 24, 5–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijtd.12167

Gillies, D. (2008). Student perspectives on videoconferencing in teacher education at a distance. Distance Education, 29(1), 107–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587910802004878

Güngör, F. E. (2020). Hastanelerde yüz yüze verilen hizmet içi eğitimin uzaktan eğitime dönüştürülmesine i̇lişkin hemşirelerin ve hastane yöneticilerinin görüşleri Unpublished Masters Thesis, Bahçeşehir University, Istanbul.

Hu, P. J., Chau, P. Y., Sheng, O. R., & Tam, K. Y. (1999). Examining the technology acceptance model using physician acceptance of telemedicine technology. Journal of Management Information Systems, 16(2), 91–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421222.1999.11518247

Khechine, H., Lakhal, S., Pascot, D., & Bytha, A. (2014). UTAUT model for blended learning: the role of gender and age in the intention to use webinars. Interdisciplinary journal of E-Learning and Learning objects, 10(1), 33–52. https://www.ijello.org/Volume10/IJELLOv10p033-052Khechine0876.pdf

Lakhal, S., Khechine, H., & Pascot, D. (2013). Student behavioural intentions to use desktop video conferencing in a distance course: Integration of autonomy to the UTAUT model. Journal of Computing in Higher Education, 25(2), 93–121. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12528-013-9069-3

Loch, B., & Leushle, S. (2008). The practice of web conferencing: where are we now? In Proceedings of the 25th Annual Conference of the Australasian Society for Computers in Learning in Tertiary Education (ASCILITE 2008). https://research.usq.edu.au/download/83f1a1603c183bc62ff5d11049aa7ec0b0b1b2d39b6be9a75793a7ddbdb388a3/188658/Loch_Reushle_2008_Pubrversion.pdf

Macht, L., Worlitzsch, D., Braijoshri, N., Bequiri, P., Zudock, J., Zilezinski, M., Stoevesandt, D., Smith, J., & Hofstetter, S. (2022). COVID-19: Development and implementation of a video-conference-based educational concept to improve the hygiene skills of health and nursing professionals in the Republic of Kosovo. GMS Hygiene and Infection Control, 17. https://www.scienceopen.com/document_file/0c07e786-46b2-40de-a944-b8f999c1a299/PubMedCentral/0c07e786-46b2-40de-a944-b8f999c1a299.pdf

Maher, D., & Prescott, A. (2017). Professional development for rural and remote teachers using video conferencing. Asia-Pasific Journal of Teacher Education, 45(5), 520–538. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866X.2017.1296930

Nguyen, X. A., Pho, D. H., Luong, D. H., & Cao, X. T. A. (2021). Vietnamese students’ acceptance of using video conferencing tools in distance learning in COVID-19 pandemic. Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education, 22(3). https://doi.org/10.17718/tojde.961828

Osei, H. V., Kwateng, K. O., & Boateng, K. A. (2022). Integration of personality trait, motivation and UTAUT 2 to understand e-learning adoption in the era of COVID-19 pandemic. Education and Information Technologies, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-022-11047-y

Reis, T., Faria, I., Serra, H., & Xavier, M. (2022). Barriers and facilitators to implementing a continuing medical education intervention in a primary health care setting. BMC Health Services Research, 22(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-08019-w

Rubinger, L., Gazendam, A., Ekhtiari, S., Nucci, N., Payne, A., Johal, H., Khanduja, V., & Bhandari, M. (2020). Maximizing virtual meetings and conferences: A review of best practices. International Orthopaedics, 44(8), 1461–1466. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-020-04615-9

Sayıner, A. A., & Ergönül, E. (2021). E-learning in clinical microbiology and infectious diseases. Clinical Microbiology and Infection, 27(11), 1589–1594. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2021.05.010

Turgut, Y. E. (2010). Factors affecting efficiency in video conferencing courses [Video konferans yoluyla verilen derslerde verimliliğe etki eden faktörler] Unpublished Masters Thesis, Karadeniz Technical University, Trabzon.

Uçar, N. (2009). Cluster Analysis. Ş. Kalaycı (Ed.), In Multivariate statistical techniques with SPSS [SPSS uygulamalı çok değişkenli istatistik teknikleri] (s. 350–376). Ankara: Asil Yayın Dağıtım.

Venkatesh, V., & Davis, F. D. (2000). A theoretical extension of the technology acceptance model: Four longitudinal field studies. Management Science, 46(2), 186–204. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2634758

Venkatesh, V., Morris, M. G., Davis, G. B., & Davis, F. D. (2003). User Acceptance of Information Technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Quarterly, 27(3), 425–478. https://www.jstor.org/stable/30036540

Venkatesh, V., Davis, F., & Morris, M. G. (2007). Dead or alive? The development, trajectory and future of technology adoption research. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 8(4), 267–286. https://aisel.aisnet.org/jais/vol8/iss4/10

Venkatesh, V., Thong, J. Y., & Xu, X. (2012). Consumer Acceptance and Use of Information Technology: Extending the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology. MIS Quarterly, 36(1), 157–178. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41410412

Wang, S. K., & Hsu, H. Y. (2008). Use of the webinar tool (Elluminate) to support training: The effects of webinar-learning implementation from student-trainers’ perspective. Journal of Interactive Online Learning, 7(3), 175–194. https://www.ncolr.org/jiol/issues/pdf/7.3.2.pdf

Wong, C. S., Tay, W. C., Hap, X. F., & Chia, F. L. (2020). Love in the time of coronavirus: Training and service during COVID-19. Singapore Medical Journal, 61(7), 384–386. https://doi.org/10.11622/smedj.2020053

Yılmaz, M. B., & Kavanoz, S. (2017). Teknoloji Kabul ve Kullanım Birleştirilmiş Modeli- 2 Ölçeğinin Türkçe Formunun Geçerlik ve Güvenirlik Çalışması. Turkish Studies, 12(32), 127–146. https://doi.org/10.7827/TurkishStudies.12064

Zoumenou, V., Sigman-Grant, M., Coleman, G., Malekian, F., Zee, J. M., Fountain, B. J., & Marsh, A. (2015). Identifying best practices for an interactive webinar. Journal of Family & Consumer Sciences, 107(2), 62–69.

Funding

Open access funding provided by the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Türkiye (TÜBİTAK).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is based on the first author’s master’s thesis, written under the supervision of the second author.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ünal, R., Yilmaz, M.B. Accepting video conferencing technology as an in-service training tool for health professionals. Educ Inf Technol (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-024-12724-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-024-12724-w